The most tragic thing in the world is an abandoned screenplay. Okay, maybe that’s an exaggeration. But at least in the screenwriting world it’s true. There have been tens of millions of abandoned screenplays over the years. Maybe more. And the reason that’s a travesty is because we’ll never know if any of those would’ve been great movies. Jordan Peele almost quit writing Get Out fifteen times. Imagine for a moment if he would’ve given in just one of those times? He wouldn’t have an Oscar on his mantle.

So let’s talk about why writers give up on screenplays. The most common scenario is you come up with an idea you’re excited about and need to write it NOW! You rip open Final Draft, start typing away, and the pages are flying by! You get through the first act in a few days! Then, seemingly out of nowhere, everything sloooowwwws down. That magical inspiration has been replaced by a dogged hatred for film. You have no idea what happened. “Everything was so easy before!” you cry out to your dog. “What changed?”

What changed is that when we come up with ideas, we’re mainly thinking about the setup. Take Independence Day. When you come up with that idea, you’re not thinking about what the characters are discussing on page 70. You’re thinking about the alien ship hovering over the White House then blowing it up. When you finish writing those scenes, you’re left with… well, you’re left with THE REAL STORY. The stuff with the characters and the theme and the relationships. And you weren’t thinking about that. This is why most screenplays die in the early stages.

Also, a new idea can feel like the greatest movie in the world! Santa Clause kidnaps Jeff Beznos because Amazon is putting him out of business? Hell yeah, you say! I can see the opening now. Santa catches his elves ordering Christmas toys from Amazon. Except three weeks later you wake up and realize this is the dumbest idea ever and it has zero legs. Of course if became a screenplay casualty. So here’s my first piece of advice to you.

Tip #1: When you come up with an idea, sit on it for at least three months.

I know that sounds crazy. But I’d even extend it to six months if possible. Bad ideas disappear quickly. Good ideas stick around. So if you’re still thinking about an idea six months after you conceived it, chances are it’s worth exploring. Not only that. But by waiting, you can add notes and flesh out the story. I think of these notes as “script ammo.” The more script ammo you have going into a script, the more likely you are to finish that script.

Okay, let’s say you come up with an idea, you sit on the idea, six months later you still want to write the idea, in the interim you’ve come up with script ammo for your idea, so you start writing your script, onnnnn-ly to end up in the same predicament. You’ve gotten a LITTLE further than you would’ve had you started right away. But still, by page 60, your creativity has taken a vacation in the Bahamas. What’s going on? I’m going to tell you what’s going on. But it’s going to make some of you mad. So if you’re easily triggered by words that rhyme with “shoutshine,” please turn away.

Tip #2: The number 1 reason for getting stuck is that you didn’t outline.

There was a time when I thought outlining was the equivalent of throwing baby squirrels in a blender – pure evil. Since then, I’ve learned that nearly all anti-outliners are beginners or intermediates who believe that outlining destroys artistic expression. Meanwhile, 99% of professionals swear by outlining. So who do you think is right? The great thing about outlining is you’ve created a safety net for idea generation. You have a plan in place for any moment you run into trouble.

I’d always found this to be the end-all be-all solution to writer’s block. You can’t be blocked if you’ve written it all out beforehand. But a writer recently brought up a good point to me: “What if you run out of ideas in your outline?”

An outline is essentially a script, only abbreviated. Just because you’re writing in outline form doesn’t mean you magically have ideas for every stage of the story. It’s arguably harder to generate ideas in outline form because you’re not building ideas on a foundation. You’re building on conceptual fragments – “idea babies” if you will. So what happens if you can’t even finish an outline?

Tip #3: An outline is useless without a pre-existing understanding of story structure.

An outline isn’t some random sequence of ideas you cobble together. It must be built on the basic tenets of story structure. That means before you write anything down, you must understand that stories have a beginning (where you set up the main character’s journey) a middle (where that journey is put to the test) and an end (where you conclude that journey). Anti-structuralists will debate this but it’s the basis for all the best stories ever told so ignore them.

The beginning of a script (Act 1) will run you about 25 pages. The middle (Act 2) will have about 50 pages. The end (Act 3) will have about 25 pages. Why is it important to know this? Because one of the reasons we give up on screenplays is fear of a blank page we can’t fill. The less we plan, the sooner that page arrives. The goal then is to distill as many of those 100 pages into manageable chunks as possible. You don’t have to write 100 pages. You only have to write 25. And then you only have to write 50. And then you only have to write 25. Then you’re done!

But 25 is still a lot when the creative juices aren’t flowing. So let’s distill the script into even smaller chunks. I favor the 8-sequence method. Act 1 has two 12 page sequences. Act 2 has four 12 page sequences. Act 3 has two 12 page sequences. Now you don’t have to fill up 100 pages. You only have to fill up 12. Then you only have to fill up 12. Then you only have to fill up 12. You get the idea. For this approach to be effective, you have to know what to do within each of these sequences. If you bear with me, I’ll help with that.

Sequence 1 (page 1-12) is where you set up your hero’s normal everyday life and then throw a problem at them that interrupts their life. Upgrade – A guy with a nice life has it ripped apart when his girlfriend is killed by criminals and he’s paralyzed.

Sequence 2 (page 13-25) is where your hero will resist the journey before coming around and thrusting himself after the goal. There’s some leniency here. Sometimes this is a “calm before the storm” sequence where the machinations of the plot force the hero into action. Gone Girl is an example of this. After Nick finds out his wife is missing (Sequence 1), he’s dragged into the investigation whether he wants to be or not.

Sequence 3 (pages 26-38) This is where your hero will begin their pursuit of their goal. This is a very logical section. Whatever your hero is trying to get, you have them take the first steps towards getting there. In Game Night, it’s going to be leaving the house so they can find the “killer” in this game. In Jumanji, it’s traveling across the countryside to find the crystal that transports them out of the game.

Sequence 4 (pages 38-50) This is where your hero realizes things aren’t going to be easy. It’s also where you begin exploring the conflict within your relationships. This is what makes scripts fun, is that they aren’t just about physical obstacles. They’re about inter-personal obstacles (disagreements, old beef, differences in world-view, deep-seated issues characters have been avoiding for years). To use Jumanji as an example again, this is the sequence where The Rock and Kevin Hart get into a big fight about the deterioration of their friendship back in the real-world.

Sequence 5 (pages 51-62) Something significant should happen at your midpoint that throws things out of whack. Your characters are forced to react to this new challenge, which distracts them from the ultimate goal. In Juno, this is the scene where Juno comes over to Mark’s house and Vanessa isn’t home. The two spend the afternoon together, where things become dangerously close to inappropriate. It changes the entire dynamic of who Juno is leaving her child with.

Sequence 6 (pages 63-74) This is where your hero gets back on track and makes a push for the goal. However, things will end up imploding on both the plot side and the character side and your hero will end the sequence at their lowest point, so low that we’re convinced they’ve failed. In A Quiet Place (spoiler), this is where the dad dies.

Sequence 7 (pages 75-87) should see your character mope around a bit before apologizing or resolving issues with other key characters. This then reinvigorates them and they either run after the Ark or confront the villain or drive to the airport to STOP THAT PLANE.

Sequence 8 (pages 88-100) This sequence should be the easiest to write. It’s the final showdown. The big climax. Tom Cruise fights Henry Cavill to stop the nuclear bombs from exploding. Harry professes his love for Sally. Natalie Portman confronts the being inside the heart of the Shimmer in Annihilation. You’ll then have 1-3 prologue scenes and you’re done.

This is a VERY simplified breakdown of the 8-Sequence method, guys. The page numbers are not to be taken literally (some sequences may be longer, some shorter, depending on your story). You’ll want to throw a ton of obstacles at your heroes during sequences 3-6 (if your recruitment of a former girlfriend scene feels lame, throw a crazy Nazi into the mix – Raiders of the Lost Ark). I also skimmed over how important character development is. When you’re struggling to fill pages, it usually means you’re not exploring characters enough. You need characters with flaws so that you can build scenes that challenge those flaws. And you need unresolved conflict in every major relationship in the movie. That conflict will be worth 5-6 scenes in the script of just them trying to hash out their differences.

Feel free to play around with the format, especially if you’re writing scripts for practice. However, if you’re a newbie, it’s a good idea to learn how to write structured screenplays. Once you learn the rules, you’ll be more successful breaking them.

Now you understand structure which allows you to properly outline which allows you to write a script without getting stuck. All good in the hood, right? Yeah, we wish. Just because you plan ahead doesn’t mean you won’t encounter problems. You’ll often find that something you were convinced would work doesn’t. Or your main character is boring. Or you encounter a plot problem that doesn’t have a solution. I once wrote a time-travel script where I needed my main character to travel through time whenever he wanted, but all the other characters could only time-travel once. I never solved the problem and eventually gave up on the script.

If you’re still running into these blocks, here are some things you can do…

WRITE DOWN THE EXACT PROBLEM – Most writers can’t get unstuck because they haven’t identified what’s wrong. Why are you stuck? Is it because you don’t know how to get your hero from A to B? Is a scene boring and you don’t know why? (Add conflict somehow!) Do you not know what your hero should do next? (Add mini-goals!) The more specific your problem is, the easier it will be to find a solution to it. It takes me awhile to fall asleep so I like identifying problems then trying to solve them as I drift into Dreamland.

KEEP WRITING EVEN IF IT SUCKS! – Writing doesn’t cure all. But it cures more than not writing. I’ve found that if you write for long enough, you’ll eventually come up with a good idea, no matter how unlikely that seems in the moment.

BOUNCE IDEAS OFF SOMEONE ELSE – Talking out loud, even with a friend who knows nothing about screenwriting, can lead to ideas. Give them a bare-bones summary of your story, tell them why you’re stuck, then throw ideas back and forth at each other. No-Judgement Zone. Terrible ideas are fine because lots of good ideas are born out of bad ideas.

THERE’S GOLD ON THE OTHER SIDE OF THAT PROBLEM – The biggest breakthroughs in screenwriting tend to come from solving the biggest problems. Some of you may have experienced this. You thought there was no way to save your script. You spent weeks trying to fix the unfixable. Then when you finally came up with the solution, it helped you see the script with a defining clarity that, up until that point, didn’t exist. There’s something about defeating tough problems that elevates your understanding of a screenplay.

IF ALL ELSE FAILS, GET FEEDBACK – If you’re truly stuck and can afford it, get professional feedback. Most readers will read unfinished scrips for a discount. And I know with me, it helps if the writer tells me exactly what’s wrong. That way I can specifically troubleshoot the problem. If you can’t afford professional feedback, make your screenwriting friends read your script. You’d be shocked at what a new pair of eyes can see that you can’t.

Also, keep in mind that there’s a reason screenplays are rewritten so much. It takes awhile to find the best version of your story. So it’s okay if you can’t figure things out right away. Follow the 8-sequence formula, get AN ENTIRE SCREENPLAY WRITTEN, even if it’s not perfect, evaluate the script for problems, then start solving those problems. The great thing about screenwriting is that there’s always something to improve. So if you don’t know how to solve one problem, work on another. And what you’ll learn is that each solved problem generates ideas that solve other problems. If you truly believe in the screenplay, guys, don’t give up on it. Don’t be Alternate Universe Jordan Peele who didn’t win an Oscar because he gave up.

Genre: Romantic Comedy

Premise: A woman finds herself pregnant with twins from two different men, a rare real-life occurrence known as “superfecundation.”

About: Just a reminder. This is the script I talked about last week. It made the semifinals of the Nicholl, which, while admirable, rarely leads anywhere. Unless your name is Savion Einstein. Einstein would later go on to sell this script to Sony Screen Gems. Some of you might be wondering, “How come a sale-worthy script didn’t advance past the Nicholl semis?” Uh, have you guys been paying attention? Nicholl wants thematically dominated scripts that have a social or global agenda only. If you’re wondering why your otherwise well-received action or horror spec didn’t get far, you now know why.

Writer: Savion Einstein

Details: 116 pages (5/24/18 draft)

I was excited to read today’s script and I’ll tell you why.

It has a low burden of investment.

Burden of investment refers to the level of complexity in a screenplay. The more complexity you add, the more is required from the reader to keep up. A script with 8 characters has a lower burden of investment than a script with 30 characters. A script that covers a setup we know well (buddy cop comedy) has a lower burden of investment than a script that explores a 16th century war in China. A script with a clean setup, conflict, and resolution has a lower burden of investment than a script that’s told out of order.

I bring this up not to warn you away from writing scripts with a high burden of investment. Godfather 2 has a high burden of investment. That movie was pretty good. Only to remind you that unknown spec scripts are the lowest rung on the ladder, which means readers are less likely to invest in overly complicated scenarios.

Which is why a script like “Superfecundation” had a good chance, and ultimately succeeded, with readers. It’s a tried-and-true setup that’s easily understood. Readers don’t have to take copious amounts of notes to keep up. They’re not going to be mentally exhausted from trying to keep up with all the characters the writer is introducing. They can just read and enjoy.

After the high burden of investment of yesterday’s script, as well as a consultation script that had such a high burden of investment, I needed to break it up into three days just to process everything, it’s nice to read a script like this, where the read is effortless.

Ellie Kessler is 29, that awful age where you feel like you need to figure everything out NOW. Which is probably why she dumps her boyfriend, Ben, a video-gaming skateboarder who thinks pot is one of the five major food groups. Ben isn’t showing the commitment required for a woman who’s about to hit 30.

After the breakup, Ellie drowns her sorrows in a crazy drunken sexscapade with her rich ex-boyfriend from college, Owen. Ellie regrets the act (or series of acts) the next morning, leaves, and doesn’t call. Not initially at least. A month later, Ellie learns she’s pregnant with twins. And that one baby belongs to Owen while the other belongs to Ben.

Naturally, it’s hard for Ellie to break the news, particularly to Ben, who didn’t even know Ellie hooked up with Owen. And it only gets worse from there, as Ellie isn’t sure which guy she wants to be with. When the guys then use every opportunity the three are together to threaten each others’ lives, Ellie is forced to break up with both of them.

While Ellie deals with the prospect of raising twins by herself, Ben and Owen continue to bicker with one another. Except then a funny thing happens. They both realize that they like each other, start hanging out together, and eventually apologize to Ellie just in time for the birth. But being friendly is one thing. The real question is: What is everybody going to do when the babies are born?

I kinda felt like I was pregnant reading this.

Don’t your emotions sway wildly while pregnant? Sometimes I was patting my belly and cheering on this new rom-com take. Other times I was throwing up into my toilet and decrying the existence of this cliched genre.

Let’s refresh our memory. What’s the most formulaic genre in screenwriting?

If you said “the romantic comedy,” then DING-DING-DING, you win a prize. For this reason, it is imperative that rom-com writers come up with a situation that we haven’t seen before. If you do that, it will lead to a series of scenarios we haven’t before. That’s Superfecundation’s biggest accomplishment. You’ve never seen a situation quite like this.

Think about it. Ellie has a complicated choice with no easy answer. She can raise twins by herself. She can raise twins with only one of the guys, leaving the other. She can choose a guy and his baby while giving her other baby to the other guy. The more you think about it, the more you wonder what she’s gonna do. And when the script stays in that space of treating the situation truthfully, it’s at its best.

Unfortunately, as the script continues, it become less and less interested in exploring this dilemma honestly. For example, all three parties go to one of those “birthing prep” classes and, by the end of the session, both men have their shirts off and the teacher is electrically shocking them to simulate how painful pregnancy can be. It’s clumsy. It’s low-brow. But more importantly, it kills the suspension of disbelief. If the writer’s going to stop taking this situation seriously, then why would we continue to do so?

Another problem is the overly clean structure. The scenario is set up with the pinpoint precision of a game show. First Ellie tells one character they’re the father. Then she tells the other character they’re the father. Then she brings them together and explains how this process is going to work. You could feel the wheels and pulleys moving underneath the page. Remember that with any script, you want the plotting to be invisible. We didn’t have that here.

I was hoping, for example, that Ellie would lie to Ben initially. Not tell him that Owen was also the father. Then have Ben find out on his own, confront her, and then see where the bloody aftermath took things. It didn’t even need to be that plot point. I just wanted something that didn’t feel so clean and “screenwriterly.” Which I know is ironic considering I was arguing for just the opposite yesterday.

But the real killer here is the ending. And I have to get into spoilers to discuss this. You’ve been warned. As we’re moving towards the end, I got the sense that we were going in the direction where all three of them were going to end up together. And as this was happening, I was saying, out loud, “Please don’t all end up together. Please don’t all end up together. Please don’t all end up together.” And when they did, I almost threw my laptop across the room.

First of all, that’s not truthful. That would never happen in real life. It’s a total lie. And when you lie to your reader, your reader hates you. How do you know when you’re lying to your reader? When the answer is easy. If everything gets wrapped up in a bow for the hero without them having to do anything, you’re a storytelling liar. You’re always on a better track when your ending is difficult.

Imagine both suitors are equal. Then imagine Ellie picks one of them. The other gets screwed. That’s a much more difficult choice. But it’s more truthful. And it’s going to generate a lot more discussion afterwards. The choice to have them all end up together made me feel like I’d just wasted the last 90 minutes of my life. That’s how insulting it was.

Which is too bad. Because there’s some good stuff here. And the good news is, the development process isn’t over. Hopefully, someone at Sony will come to their senses and provide this script with a different ending. Or, even better, shoot several endings and let the audience decide. I have a strong feeling they’ll decide against this one.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Any solution in your story that’s easy should be treated with suspicion. It typically means you’re providing an “out” for your characters. It’s always more compelling when the characters have to make tough decisions, and those decisions have harsh consequences, even if, as was the case here, it’s the final decision of the story.

Genre: Drama/Crime

Premise: (from IMDB) When two overzealous cops get suspended from the force, they must delve into the criminal underworld to get their just due.

About: S. Craig Zahler is somewhat of a screenwriting legend. At one point he’d sold over a dozen [unproduced] screenplays. Since then, Zahler’s graduated into directing, and his newest project is the delicately titled, “Dragged Across Concrete.” Sounds like a biopic about safe spaces. Zahler will be bringing back the star of his previous film, Vince Vaughn, as well as adding Mel Gibson to the mix (who it was announced yesterday is directing a remake of The Wild Bunch). Concrete is already poured and is slated to come out later this year.

Writer: S. Craig Zahler

Details: 157 pages!

If you’re new to the site, take a look at the right panel where I’ve listed my Top 25 favorite scripts. You see number 3? That was written by this guy. S. Craig Zahler has one of the most powerful literary voices in the screenwriting community. When you’re reading a script by Zahler, you know it instantly. While that’s a big advantage in the spec world, it can be a roadblock in the “get movies made” world. Studios don’t really know how to pair up unique voices and directors. This is why most voice-y screenwriters direct their own material (Tarantino, Sophia Coppola, Wes Anderson, Paul Thomas Anderson). It took Zahler a long time to realize that. But once he did, his career trajectory shot up. He started with Bone Tomahawk, moved on to Brawl in Cell Block 99. And now he’s going to drag some poor soul across concrete. Let’s see how he did, at least on the writing end.

20-something Henry Johns has just got out of prison to find that his mother has taken up prostituting herself and using all the money to shoot heroin into her veins. Not a good look since she’s supposed to be taking care of Henry’s little brother. With no work prospects on the horizon, Henry knows that the only way he’s going to flip this situation around is by plunging back into the crime world.

Across town, cops and long-time partners Brett and Anthony are dealing with their own issues. Anthony’s thinking of proposing to his girlfriend despite suspicions that she’s not that into him. And Brett’s dealing with a wife who’s struggling with MS, and a daughter entering puberty, which has gotten the attention of all the boys in the yard, that yard being located in one of the worst neighborhoods in the city.

Things come to a head during a routine bust when Brett is videotaped roughing up a perp. The video goes viral and gets the both of them suspended for six weeks without pay. Sick and tired of his shitty life, Brett decides to do the unthinkable: Use a criminal contact to find out where the next big drug deal is going down. His plan is to come in when they least expect it, take the money, and head to greener pastures with his family. While Anthony isn’t as keen on the idea, he wants to help his friend.

So Brett and Anthony stake out the dealer’s home, and when the crew finally arrives, we notice that one of the dealers is Henry Johns. Our off-duty cops follow Henry and his crew to the exchange spot, except something is off. It turns out they’re not doing a drug deal. They’re robbing a bank. Brett thinks of calling an audible until he realizes that the payday is going to be 10x what he originally assumed.

Brett and Anthony wait for the thugs to finish the job before following them home. All parties end up at an abandoned gas station, where a wild showdown occurs. People start double-crossing each other while others are forced into temporary alliances. Despite Brett doing everything in his power to get that money, it becomes clear to us that the only person who’s going to make it out of here alive is Father Greed.

The first question you’re probably asking is, “How did you make it through 157 pages, Carson?”

It wasn’t easy.

For sometimes better and sometimes worse, Zahler likes to draw out his stories. You love it when he’s setting up rich characters with complex relationships. You hate it when he extends what should’ve been a 2-minute scene into 15 minutes of “well that could’ve been shorter.”

I mean the stakeout sequence is 10 pages long. You don’t need that. That’s not to say you can’t draw out certain scenes. But the degree to which you can stay with a scene is directly proportional to how interesting the situation is. A stakeout is boring. So of course we’re going to be bored if we sit around for 10 minutes.

On the flip side, the next scene, where they discreetly follow the criminals to their rendezvous point, felt perfect at 15 pages. Why? Because there’s an ongoing sense that they might be spotted. Because the characters we’re watching have a high-stakes goal. Because a mystery emerges about what the criminals are actually up to. Better situations can be extended out.

This was an issue I had with Brawl in Cell Block 99 as well. It was taking too long to get to the point of the movie. All the best stories (in any medium) become interesting once a problem arises. If I tell you a story about my drive through Death Valley and I never introduce a problem, you’re either going to tune me out or tell me to shut up. If I tell you a story about driving through Death Valley and then my car breaks down in the middle of nowhere on the hottest day of the year (a PROBLEM), you’re going to be captivated. Stories don’t start until there’s a problem.

The “problem” in this story, which I would argue is when Brett realizes he needs to get his family out of this neighborhood, doesn’t come up until 50 pages into the script. While I’ll never say that certain plot points need to happen by certain page numbers, every page after page 15 that you don’t introduce the central problem of your story is dramatically increasing the likelihood that the reader is going to tune out.

In my case, I knew this going in, because I know Zahler’s writing so well. That allowed me to stick with the script longer than I typically would. And once we get to the problem, the movie picks up considerably. Actually, you could make the argument that a lot of those scenes that seemed arbitrary at the time became essential anchoring points.

For example, we meet Sara, Brett’s 12 year old daughter, walking home from school in a shitty neighborhood. A few boys harass her, and we get the sense that just walking home for this girl is dangerous. It’s a good scene but all I could think was, “This is a long script. Can’t we cut this scene out?” However, later, when Brett’s wife makes the argument that things are only going to get worse for Sara if they stay in this neighborhood, us experiencing Sara’s harassment becomes critical in understanding why Brett makes the choice to steal money.

Not to mention, the climax makes all the setup feel worth it. It was a clever move by Zahler to introduce Henry Johns early, ignore him for the first half of the second act, then bring him back as a point man in the robbery. Creating complicated scenarios where we’re not sure who we’re rooting for – the good guys or the bad guys – isn’t easy to do. That legwork of setting up both Brett’s and Henry’s shitty lives – even if I was bored watching them at the time – paid off in that I wanted both of them to succeed, something I knew wasn’t going to happen, which is exactly why I was so drawn in.

Despite that being well-done, I still think Zahler’s too self-indulgent. Even five minutes in a movie is an eternity. You can get any point across in 5 minutes. But with Zahler, he’ll double that without a second thought. And while these endless scenes never derail the movie, they certainly wreak havoc on the pacing. I hear the director of The Outlaw King cut 20 minutes off his movie after the negative test screening at TIFF. I would suggest Zahler do the same. You don’t want to waste a movie with character work this strong.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

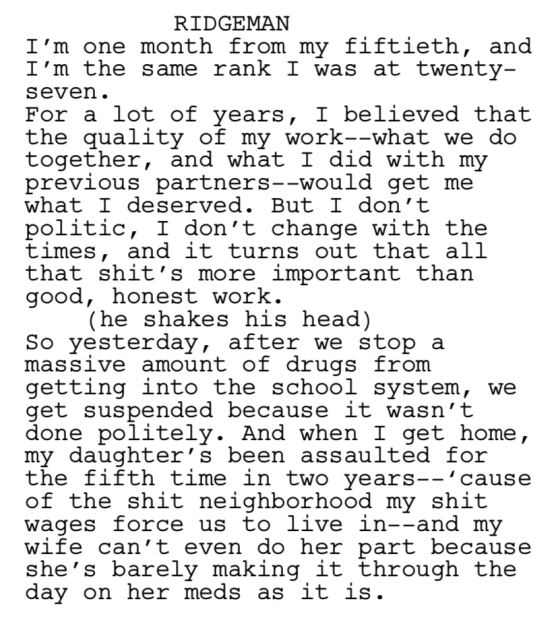

What I learned: The stronger the motivation, the more we’ll root for your hero. I love how we get Brett’s motivation in a single monologue. Anthony is pressing him and pressing him and pressing him on why he’s risking everything for this money. Brett finally cracks…

What I learned 2: Now some of you might say, “But Carson! Isn’t that on-the-nose dialogue!?” No! It isn’t. Don’t you guys remember last week’s dialogue article? Number 2? A character can reveal backstory (or other exposition-driven information) as long as he’s pushed into it.

Genre: Drama/Supernatural

Premise: (from IMDB) June and Oscar live a comfortable but very predictable wedded life when suddenly they find themselves in a completely unexpected situation, raising questions about love and marriage.

About: Alan Yang, creator of Master of None, got this gig when Fred Armisen and Maya Rudolph, who have been wanting to work together forever but couldn’t find the right project, decided to have a “reverse casting” whereby they brought writers in to pitch them on a show they’d be in. Yang and Matt Hubburd were the winners with this simplistic yet trippy idea about marriage that has quickly become one of the most buzzed-about shows of the year. The only reason it isn’t a bigger deal is because it’s on Amazon Prime and nobody knows how the hell to get on Amazon Prime.

Writer: Matt Hubbard and Alan Yang

Details: 8 half-hour episodes

Before I get into my review of Forever, I want to discuss two movies that bombed this weekend: This Is Us 2 and Assassination Nation. I kid I kid. Life Itself and Assassination Nation. Both films made a COMBINED 3 million dollars despite being shown in a combined 3000 theaters.

So what’s the lesson here? Movies must fit inside a marketing campaign that the average moviegoer understands. For example, when you market a bunch of people getting together to rob a bank, the average moviegoer understands that that’s a heist, and therefore, if they like heist films, they will likely enjoy themselves. But when you look at the trailer for Life Itself, where is the marketing familiarity? It’s just characters talking to each other and crying. You can see that on television but you don’t see it on film anymore. That’s confusing to the average moviegoer. I want to be clear about this – If you write a script that cannot fit inside a pre-established marketing campaign, nobody’s going to want to see it.

That’s not to say you can’t write a movie like this for a streaming service. But it’s not going to work on the big screen.

Assassination Nation is a tougher nut to crack but, in the end, suffers for the same reason. I can see how producers could talk themselves into this movie working. It’s the #MeToo movement. It’s female empowerment. It’s a bunch of women kicking ass. They were probably thinking people would see the movie because the advertising would celebrate these messages. But here’s the problem. Nobody who saw this poster understood what the movie was about. I don’t understand this marketing campaign because I haven’t seen this type of marketing campaign before. So why would I risk $20 on a film that I don’t understand? Why would anybody?

Ironically, if the movie had a single woman holding a gun instead of four women, it would fit into one of the most successful marketing campaigns we have at the moment. That’s what I want you guys to remember. If your script doesn’t fit into a marketing campaign that you’ve seen before, it’s going to have a tough time finding an audience.

Which leads us to Forever, a show that 10 years ago, someone would’ve tried to write as a feature. These days, because it doesn’t fit into any known marketing paradigm, it makes a lot more sense to explore as a streaming show. Now we all know how I feel about experimental storytelling. One of the common criticisms of me is that I don’t understand anything unless it abides by the rules. That’s not true. What I don’t understand is anything that tries to pass sloppy off as visionary. Let’s hope Forever doesn’t fall into that trap.

By the way, this show is one giant spoiler. If you want to enjoy the show in all its glory, I recommend watching it first then coming back to this review.

June and Oscar are a couple of semi-loners who were weird enough that they had trouble finding mates early on in life. Therefore, when they meet each other, it’s not clear whether they’ve really found “the one” or they’re just happy to have found “someone.” Either way, they’re much happier together than they were alone, and that’s all that matters.

There are a couple of sticking points in June and Oscar’s marriage. The first is that Oscar likes routine. He likes eating the same dinner every night. He likes going to the same lake house every year. He’s a creature of habit. June enjoys doing these things because Oscar enjoys them. But after awhile, she gets sick of them. And therein lies their issue. Neither June or Oscar ever tells the other how they feel. This results in resentment, particularly on June’s end.

June tries to remedy this by suggesting something different this year: SKIING. Oscar doesn’t like the idea because it’s new, but eventually gives in. After the two hobble around the slopes for awhile, Oscar loses control and crashes into a tree, dying. That’s the end of the first episode. The second episode is about June grieving the loss of Oscar. And after a long year, she finally gets a big promotion at work, which includes a trip to Hawaii. As they prep for takeoff, June opens a package of nuts and ends up choking on them. She dies. That’s the end of episode 2.

In episode 3, June wakes up in the afterlife, which is basically a more pleasant version of suburbia. Oscar is thrilled that she’s arrived and informs her that now they get to stay here forever. June isn’t so sure she likes that idea. By the end of the week, Oscar is back to his old routine, and June can’t help but think, “Is this it?” For the first time, she starts to challenge Oscar on his boring existence, and their perfectly pleasant relationship is thrown into upheaval. When June finally leaves him, Oscar will have to decide if this new June is really worth fighting for.

Let me start by giving everyone some good news.

I remember reading Alan Yang’s first script. It was a Black List Script called Gay Dude about a guy who learned that his friend was gay. The script was SO AVERAGE. It was the definition of average. Like mind-blowingly average. Average enough where I’m surprised he made the Black List with it. However, fast forward to 2018, and Alan Yang has had two of the buzziest shows on television.

This should serve as a reminder that screenwriting is a process. You can get better. You don’t have to win it out of the gate. Do your best, and even if it’s average, that’s a start. If you can improve at the rate Yang has (or faster since you have Scriptshadow on your side), you could be writing great TV shows in five years.

One of the reasons Yang has broken out like he has is that he understands the new TV landscape better than most. He knows that this is a new medium, and with it comes a new set of rules. You have to try things that you haven’t tried before if you want to stand out.

I’ll give you an example. The hook of this show doesn’t arrive until Episode 3. Oscar dies at the end of episode 1. June dies at the end of episode 2. And the afterlife doesn’t start until episode 3. Now the 55 year old screenwriter who used to write on CSI doesn’t understand this. To him, you would’ve needed to get to the afterlife by page 15 in your pilot. By the end of the first episode at the latest. But it’s a new dawn and a new day. You gotta start thinking outside the box.

Once we get to the afterlife, Yang and Hubbard start using more traditional screenwriting approaches. Whenever you have a unique hook, you have to EXPLOIT THAT HOOK. If you’re not looking for plot threads that could ONLY HAPPEN in YOUR UNIQUE SHOW, you’re not doing your job.

In Forever there’s this teenager character, Mark. He died in high school in a car crash and therefore is forever stuck in a teenager’s body. He’s begrudgingly friends with Oscar and in one of the episodes, they see what looks like two teenagers and their mom up ahead. Mark freaks out. “Uhh, let’s go back home.” “Why?” Oscar asks, before realizing that Mark likes one of the girls. After an argument, Mark agrees to go talk to the girls. “So which one do you like?” Oscar asks. “That one,” he points. “Oh,” Oscar says, seeing the cute girl he’s pointing to. “Redheads, nice.” “No, not her. Her.” And he points to the overweight 60 year old mother.

It turns out that that mother went to high school with Mark, and she was “the coolest girl in school.” She just ended up dying 45 years later than Mark. So Mark goes and talks to her and a major subplot of that episode is the two going on a date. That’s good writing, people. You find plotlines that could only happen in your concept. You do that and you’re guaranteed originality.

The show is also a constant stream of unexpected choices. This is something I barely see as a reader. All writers are making the same choices as everyone else. I’m always 30 pages ahead of the script. And the funny thing is, all it takes to break this pattern is to be conscious of it. When you decide on an idea, ask yourself if you’ve seen it before. If you have, challenge yourself to come up with something else.

Take June’s death. As episode 2 draws to a conclusion, and June is heading to her plane to fly to Hawaii, we get the sense that her death is coming. It’s pretty obvious. Naturally, what are we expecting her death to be? Her plane’s going to crash, right? I was 99% sure that was the choice that was coming. Instead, the stewardess hands June a bag of macadamia nuts, and June excitedly downs one, only to choke on it. Never expected that in a million years.

Forever is a great show until it hits its final two episodes. What Yang and Hubbard are so good at – finding drama and entertainment in the most mundane conversations – is jettisoned in favor of a clunky plot where June treks to another town and Oscar chases her. It’s the only blemish on an otherwise perfect show, and should serve as a lesson to screenwriters everywhere. Don’t go away from the stuff that defines your show. The same thing happened with Seinfeld. They tried to force a plot onto the finale on a show that was anti-plot. But even with that mistake, the characters were so great in this, I still left the show impressed.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[x] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: With television, you need to identify a core problem at the heart of your main relationship which you will then explore, both directly or through subtext, every time the characters are together. Here, it’s that June and Oscar never talk about their problems with one another. This means that each has a long list of built-up frustrations that are simmering underneath the surface every time they chat.

Genre: Musical Horror Comedy

Premise: In 1985, an eager teen in search of an exciting summer signs up to work at a musical summer camp where counselors are stalked and murdered by an unknown assailant.

Why You Should Read: A Killer Musical is three things: a musical, a slasher movie, and a comedy, in that order. I wanted to have legitimate song and dance numbers to go along with the jump scares and brutal murders of a slasher film, all while keeping the humor from moving into Scary Movie territory where the characters behave as if they are aware that they are in a horror film. — This script is for everyone that has watched Friday the 13th and said to themselves, “Why aren’t there any song and dance numbers in this camp counselor murder romp?” — I’ve only been lurking Scriptshadow’s AOW for a short while and I haven’t seen a musical yet. Perhaps it’s time?

Writer: Chris Hicks

Details: 97 pages

As I lament the fact that I don’t have a Playstation 4 and therefore cannot play Red Dead Redemption 2 – sad face – I’m reminded that all is not lost. Maniac, by new Bond director Cary Fukunaga, debuts today on Netflix, and I’m going to be reviewing it Monday. The series is supposed to be unlike anything you’ve seen before, so it’ll be an interesting watch. Make sure to catch at least the pilot episode so you can participate in the discussion.

Speaking of unique ideas, we’ve got a true original one today with our Amateur Offerings winner. I can count the number of musicals I’ve reviewed on Scriptshadow on one hand (There’s La La Land, there’s Bob the Musical, there’s… any more?) and there’s a good reason for that. Musicals are the hardest genres to critique in the script stage. How can you adequately examine something without hearing the very portion that defines it – the music?? I don’t know. But I’m going to try!

It’s 1985. 17 year old virginesque Alyson has just accepted a counselor position at a brand new musical camp in the woods. She’ll be joining her chain-smoking slutty best friend, Nikki, who will be bringing along her boyfriend, Brett, and his hot best friend, Tommy, who Alyson immediately has eyes for.

The group will meet up with a second older group led by Mitch and Colleen, a couple who’s been in one endless fight since they got together, and the Tweedle-Dee and Tweedle-Dum of the gang, Lonnie and Danny. The goal is to get to the location and prepare it for camp, which will begin next week.

What nobody here knows is that the area of woods they’re going to is CURSED! People have been disappearing there since 1865. At least that’s what the psycho gas station attendant tells them. Needless to say, the second they show up, people start getting killed. A theater-masked assailant (half his mask a smiling face, the other half crying, with a stitching down the middle) who carries a makeshift axe welded to an old guitar frame begins killing the poor counselors one by one!

Oblivious to the mayhem, our Final Girl, Alyson, falls in love with Tommy, only to learn that he’s gay. And to make matters worse, after recovering from the embarrassment, she finds that half the group has disappeared. As she starts looking into the mysterious development, it becomes clear that they’re in serious danger. Can she use the power of song to escape? Or will she end up like everyone else in the crew, a one-hit wonder?

I’ve never truly understood the slasher formula.

The point is to create a group of characters we dislike enough that we want to see them killed, however, keep them just likable enough so that, in the meantime we’re not bored by them. I don’t know how you do that. And I suspect that that’s one of the reasons the genre fell out of favor in the 2000s. Audiences aren’t interested in watching movies where they don’t care if the characters live or die.

To revive the formula, you’re going to have to do something different. And give it to Chris Hicks for infusing the genre with just that – MUSIC!

I love this idea. It’s inherently ironic (singing chirpy songs while characters are brutally murdered) and provides the script with that “same but different” element executives are always pining for.

But ideas don’t matter unless the execution is in place. And I’m not sure the execution is there yet with A Killer Musical, beginning with the awkward setup. I went into this thinking that Alyson was one of the camp members, not a camp counselor. She was still in high school so it seemed like a logical assumption. Therefore it was very confusing when she got to the camp and started preparing it for other camp members. I kept thinking, “I’ve never gone to a camp where I had to first prepare the camp.” I eventually realized she was a counselor but that could’ve been clearer.

Once I got past that, I did like what Chris did. Having to prepare the camp gave the characters something to do. Lots of writers have trouble with this. They don’t give their characters any goals and therefore struggle to come up with things for them to do. As a result we get a lot of the cliche scenes like, “Wanna join me for a smoke on the porch,” or “Let’s play Truth or Dare.” By needing to prepare the place, you place the characters in a number of situations where they are isolated and can therefore encounter our stalker.

But what the success of this script really comes down to is: Are the songs enough to invigorate a tired concept? And in this iteration, I would say no. The reason being that while the songs are informative, they’re not clever enough. I was looking for more jokes in the song-writing, more clever asides. Instead, many of the songs were exposition-driven, and fairly straight-forward exposition at that.

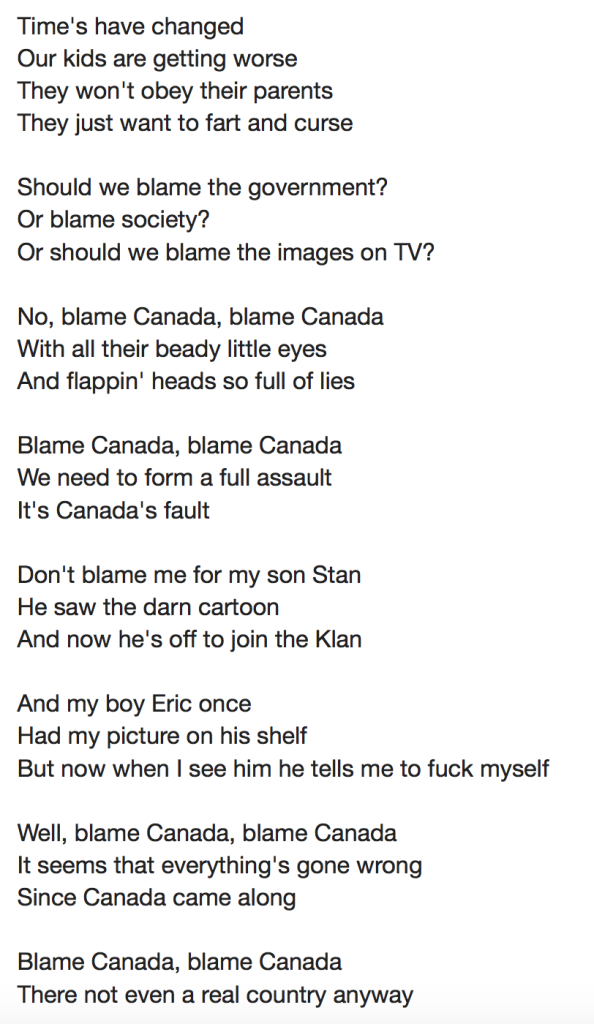

The gold-standard for comedy musicals now is the South Park guys, Matt Stone and Trey Parker. These guys are so funny and their song-writing masters the art of being expositional, pushing the story along, AND throwing jokes in there. I wanted more of that in A Killer Musical. Here’s one of their most famous songs, Blame Canada.

To Chris’s credit, he does let loose, but it happens too late – all the way in the third act. One of my favorite moments in the script was when a couple of dead characters reanimate and start sing-narrating Alyson’s escape sequence. It was fun and clever – exactly what I was looking for. But it was TOO DAMN LATE. I was like, “Where was this at the beginning??” And while I understand the need to build up to that moment, I felt Chris took too long to get there. I mean, this is a SLASHER MUSICAL. We expect crazy. You can start giving it to us earlier.

I will say I liked the killer. I liked that his main weapon was music-inspired. I thought the mask was great. These movies are so dependent on the mask because that’s what’s going to be used to market the film and a good mask can get you 10 million bucks on opening weekend. And I loved that the kills were musical-inspired. My favorite was him sneaking up on a character with cymbals and then slamming them together on her head, exploding it like a watermelon. Only thing that was missing was him saying, “Well that was cymbollic.”

But for a script with a hook this zany, it was surprisingly tame for the majority of its running time. If I were Chris, I would go back through this and let loose, particularly with the song lyrics. I think this script is worth pursuing because I can see it as a movie. But the author needs to un-muzzle himself and deliver on the promise of the premise much earlier than the third act.

Script link: A Killer Musical

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Readers loooooooove scripts with this much dialogue. When a reader sees a script like this, it’s heaven. They know that their read time has just been cut down by half an hour, possibly more. I’m not saying that every script should have tons of dialogue. I’m only saying that if all else is equal and you’re trying to decide between a dialogue-driven script and a description-driven script, pick the dialogue one.