If you’re anything like me, you need the occasional break from the Hollywood tentpoles, the Oscar hopefuls, the thrillers and the chillers, the biopic caterpillars. Ya just want to laugh sometimes, man! So ya go over to the comedy section of your digital rental service and try to find something that either looks good or has an actor in it you like. Then you press the magical download button and hope for the best.

While going through this process last week, I came across a comedy called “Why Him.” You may have heard of it. It’s a movie that stars Breaking Bad vet Brian Cranston along with James Franco. In it, a father flies with his family to California to meet the man who wants to marry his daughter.

Now, when I originally saw this trailer, I said, “That movie isn’t going to work.” And I knew exactly why it wasn’t going to work. But three months later when the bar is lower and the picks are slimmer, you start movie gambling. I looked up the writer and director of the film and was surprised to see that it was written by the same writer of one of my all-time favorite comedies, “Meet the Parents.”

So I thought, “Huh. I have to give this a shot now.” And I gave it a shot. And it turned out to not only be bad, but embarrassing. However, I already knew this would be the case when I originally saw the trailer. And chances are, so did you. Which is why you didn’t waste your hard-earned money like I stupidly did.

But why, specifically, was this movie doomed before it was written?

It was doomed because it had a faulty concept.

I’m going to get technical here, so stay with me. But the reason the concept was faulty was because it didn’t have clarity of conflict.

Clarity of conflict – When the conflict at the center of the movie’s concept isn’t clear to the viewer.

That may sound like screenwriting mumbo-jumbo, but it’s imperative that every movie you write have clarity of conflict. If you don’t get this one thing down, your movie is doomed. And I’m going to show you why.

But first, I need to teach you what conceptual conflict is. When you come up with an idea, you must also come up with the main conflict within that idea. Let’s say I pitched you a movie. “It’s about a funny irreverent superhero who’s this crazy dude and he says all these crazy things when he’s doing stuff. It’s insane.” You’d (hopefully) look at me and say, “Annnnd?” The reason you’d say that is because I never told you what the central conflict was in the movie.

Had I instead said, “It’s about a funny irreverent superhero who vows revenge on the super villain who tortured and maimed him for a decade,” you’d better understand the movie because I gave you the central source of conflict. Without a central source of conflict, a movie isn’t a movie. It’s an idea.

The next step is making sure that this conflict is clear. If the audience isn’t clear on what the conflict is or how it works, it’s like being thrown into a sport where you don’t know the rules. You have no idea where to stand. You have no idea where you’re going or why you’re going there. You’re not even sure what the point of the game is (I imagine this is what it’s like to play Cricket).

The reason Meet the Parents is one of the most popular comedies of all time is that it has one of the clearest conflicts of any comedy ever. A young man must win over the tough-as-nails father of the girl he wants to marry. You understand what’s going on INSTANTLY. You could explain that concept to anyone walking down the street and within five seconds they’d get it.

That’s because the clarity of conflict is so strong.

I understand the “Why Him” pitch in theory. I could see it going down in a boardroom like this: “What if we did Meet the Parents… but in reverse? So it’s actually the father who goes to meet the potential son-in-law.” Okay, on the surface, it’s not terrible. Every father’s nightmare is their daughter marrying a deadbeat loser. There might be a movie here.

BUT THAT’S NOT THE MOVIE THEY MADE.

Here’s what they did instead. They made the daughter, Stephanie, fall in love with a guy who was a bit of a douche, but WORTH 100 MILLION DOLLARS.

Why is this a problem? It’s a problem because now, it’s not clear what we’re supposed to think. I’d understand being upset if Stephanie was going to marry some drug-dealing deadbeat living in his mother’s basement. But she’s marrying a man who’s incredibly rich and successful who she’s head-over-heels for. As an audience member, I’m thinking, “Wait, why is that a bad thing?”

Due to our confusion, we figure there must be something wrong with Laird. He must be a bad guy. But it turns out he’s a really good guy, further muddying the conflict waters. The movie poster is telling me I’m not supposed to like this boyfriend, but my logical mind is saying he’s fine. In fact, this is probably the ideal guy you’d want your daughter to marry.

Now you might be saying, “Okay, Carson. You’ve proven they did some nerdy inside baseball screenwriting thing wrong. Who cares?” YOU SHOULD CARE. Because the conflict at the heart of your concept dictates EVERYTHING that comes after it. Every scene between Laird and the dad will carry an undercurrent of, “Wait, what am I supposed to be feeling right now?” because what the movie is telling me I’m supposed to be thinking isn’t matching up with what I’m actually seeing! And if that’s what I’m concentrating on, I’m not laughing.

If you watch the original Meet the Parents, you’ll see that every joke is built off of that central conflict. When Greg loses the cat, it’s not some goofy, “Zoinks! I lost the cat!” scene played for zoinksy cat laughs. That cat is Jack (the father’s) most prized possession in the entire world. If Greg doesn’t find that cat before Jack comes back – a man who already hates him – he’s fucked! He loses the woman he wants to marry!

In Why Him, since jokes centering around the central conflict don’t work, the writers start bringing in jokes that have nothing to do with the concept. For example, a character is brought in who’s half-butler, half-ninja, whose job it is to… well, let’s be honest. He’s there to act wacky and do a lot of off-the-wall shit because the producers realized nothing else about the comedy was working.

This is why clarity of conflict is so important, guys. Everything else falls apart if we don’t understand what the central conflict in the story is.

In Arrival, the central source of conflict is communication.

In The Martian, the central source of conflict is long-term survival.

In The Revenant, the central source of conflict is revenge.

In Trainwreck, the central source of conflict is the main character sabotaging herself.

In Flight, the central source of conflict is addiction.

There will be lots of little minor conflicts along the journey in every movie. And the more complex your movie is, the more of those you’ll have. But you must have a dominant central conflict driving your story and it must be CLEAR. For example, Braveheart is a really complex movie that covers a lot of time, involves multiple women our hero falls in love with, contains a lot of political maneuvering, as well as lots of battles. But the central conflict is the English. That’s what the movie always keeps coming back to – securing freedom from the English.

So I beg of you, please, get your central conflict in order. Make sure it’s clear. When you have that clarity, that’s when someone hearing your pitch or seeing your trailer just “gets it.” They immediately understand what the movie is about. Hopefully this brings your concepts to life. Good luck!

Genre: Drama

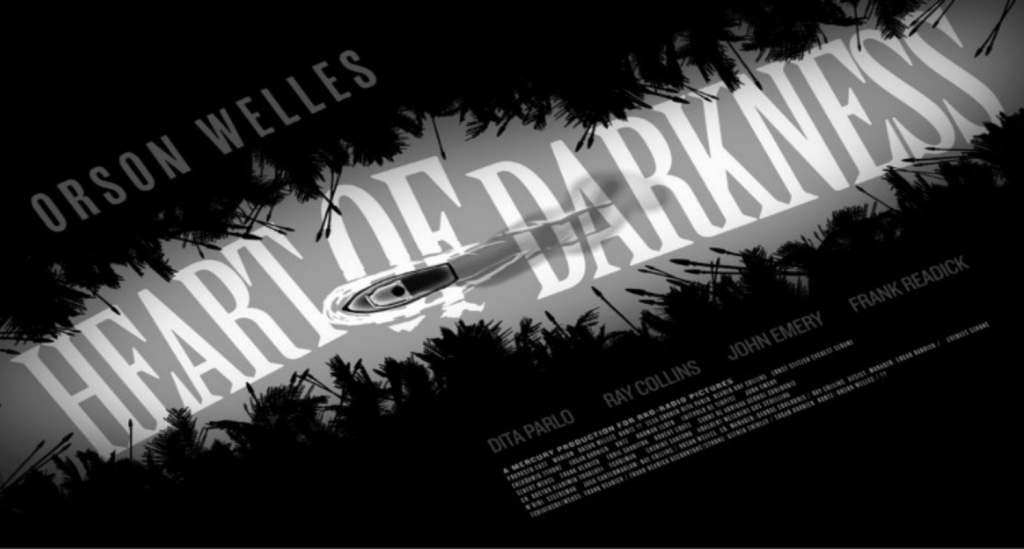

Premise: A steamboat captain is recruited by a British ivory company stationed in Northern Africa to find one of its men who’s lost in the jungle.

About: Best known for tricking radio listeners into thinking the earth was under attack by aliens from Mars, and for creating the “best film ever made” in Citizen Kane, Orson Welles is also known as the poster child for lost opportunity. His choice to make a movie about one of the most famous newspaper magnates ever to live (Randolph Hearst) during a time when newspapers were so powerful, they shaped our very reality, Hearst, who knew every bigwig in Hollywood, demanded Welles not be able to make any more movies. And that’s pretty much what happened, with Welles only trickling out a handful of films during his career. Heart of Darkness was a casualty of this blackballing, and a movie Hearst desperately wanted to make.

Writer: Orson Welles (based on the novel by Joseph Conrad)

Details: 185 pages

In one of the most famous movies never made, Orson Welles had plans to be the first filmmaker ever to shoot an entire movie from the main character’s POV. While this is merely an artistic choice today, back then, with the weight of the cameras and how difficult it was to set up even a basic still shot, the process for filming a 2 and a half hour POV movie would’ve been an almost impossible undertaking, which is at least partly why this movie never got made.

It should be no surprise that Welles wanted to tell this story. The dude is dark. He routinely spat out quotes like this one during his life: “We’re born alone, we live alone, we die alone. Only through our love and friendship can we create the illusion for the moment that we’re not alone.” Holy barnacles, batman. Someone please check the going rate on nooses on Amazon.

Heart of Darkness starts out, rather amusingly, with Orson Welles staring at us while we’re lodged inside a bird cage. He then tells us, the audience, that in this film, we’ll be seeing the movie through the main character’s eyes. He then shoots us, killing the bird version of ourselves, to show us just how powerful this device will be.

Then, even more amusingly, as if he didn’t think that would be enough to convey just how outrageous this first person approach will be, he places us in the shoes of a prisoner, then walks us to an electric chair and executes us. If we hadn’t understood the device that would be guiding us through the movie before, we did now.

That leads us to Marlow, our main character, who also happens to be us. We’ll be experiencing the movie through Marlow’s eyes. Marlow is an American steamboat captain who’s been tasked to go to Northern Africa to find a missing member of “The Company,” that being an ivory trading company based out of Britain.

The missing person is the mysterious Kurtz, who’s so elusive we’re not even sure what he does. Kurtz is located deep in the jungle, up one of thousands of river tributaries, at a remote station where he’s pulling in more ivory than the rest of the company combined. But Kurtz hasn’t written the company in awhile, and people are getting worried.

So Marlow, or “us,” team up with Kurtz’s beautiful and flirty fiancé, Elsa, to find this man that nobody can stop talking about. The further inward they go, the clearer it is that this place is hell on earth, a breeding ground for disease and death. The few who somehow escape these scenarios, often end up crazy. That, they fear, is what’s happened to Kurtz, and if we don’t find him soon, what may happen to us.

Welles wrote this script when he was 25 years old, and it feels like it. Those early 20s scripts are always the most ambitious as you want to change the world and redefine the medium. You’ll throw in any and every weirdness you can just to stand out. Who cares if it serves the story. As long as it gets people talking!!

With that said, if there’s anyone who’s capable of getting away with that, it’s Orson Welles. Every choice he made in Citizen Kane, someone told him he couldn’t do it and he did it regardless. Greatness is never born out of someone saying, “I want to do this exactly the same way everyone else has done it.” So there’s something to be said for Welles’ gung-ho attitude here. And, in his defense, the subject matter warrants taking chances.

But the first person perspective, while cool in theory, presents several storytelling problems. And the mistakes made from scripts like this one, as well as its cohorts that eventually made it to the screen, only to quickly be forgotten, are likely what inspired the first generation of screenwriting professors to say, “Maybe doing it this way doesn’t work.”

What’s one of the first things they teach you in Screenwriting School? The main character needs to be active. Why does the main character need to be active? Because active characters drive stories and because audiences like people who DO things as opposed to people who REACT to things.

And that’s pretty much all Marlow does, is react. In fact, the entire movie consists of him watching OTHER PEOPLE do things. True, he is the captain, so he is taking our characters to Kurtz. But there’s never a situation where Marlow is like, “We need to go that way!” And he runs to the steamboat room and starts pouring on more coal before running out and pulling a rare Fast And Furious’esque figure-8 steamboat move to barely make it into the Katonka River.

It’s more like, someone will come up to him and say, “Hey, how you feeling?” And Marlow will say, “All right. I wonder what the weather is like back home.” There are a lot of interactions like that, giving us a character dominated by a whole lot of inactivity.

It’s not a total bust though. Heart of Darkness conveys just how popular build-up can be. If you build something up enough, the audience WILL stick around until that thing arrives. I don’t think I’ve ever heard one thing (the name “Kurtz”) mentioned so many damn times in a single script.

Every other word out of someone’s freaking mouth was “Kurtz,” to the point where even though I was bored to tears because nothing else was freaking going on, I wanted to find this Kurtz fellow! I mean, with so many people talking about him, he had to be worth the wait, right?

What I also found interesting was that despite this novel being written over 100 years ago, that even back THEN they were still using love triangles. I say that because you think of a love triangle as a cheap literary device used to stir up some artificial conflict. But the magnetic and flirtatious Elsa working her magic on Marlow while her fiance, Kurtz, draws closer every minute, was of the more dramatically compelling storylines in the script!

The weird thing, though, is that the very thing I found gimmicky at first – Welles’s cheesy masturbatory opening sequences – was exactly what I craved more of as we made it past the century page mark. The script gets so bogged down in its dark subject matter and relentless attention to camera detail (seriously, the word “CAMERA” was easily used over 600 times in this script), that there wasn’t any fun left. Add on a protagonist who just watches everyone else do things without doing anything himself and you can see why something like this would get boring quickly.

The only thing to keep our interest was that damn Kurtz. But because, at a certain point, that’s all the story had to offer, even I had to dive into the water and swim back to shore. This would’ve been an interesting experiment had it ever been produced, but very likely a failed one. That’s exactly what the studio head said to Welles at the time. And do you know what Welles came back with? “No problem. I have another idea. It’s called Citizen Kane.”

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: You are not as clever as you think you are. When you think that you’re rewriting the cinematic language by talking directly to the reader or going first person POV for an entire script? Know that there was a script written as far back as SEVENTY SEVEN YEARS AGO that was doing the same thing. When it comes to screenwriting, choose the most compelling story you can write over writing something gimmicky with tons of bells and whistles. If Orson Welles couldn’t pull it off, you probably can’t either.

Genre: Dark Drama

Premise: When a young girl named Allison Adams goes missing, four other women named Allison Adams find themselves at first peripherally, and then directly, pulled into the mysterious disappearance.

About: Allison Adams made this past year’s Black List, was written by actor Devon Graye, and is really fucked up. Now, you may ask how anyone could write something so fucked up. Seems like a good time to throw this nugget at you: Graye played Teenage Dexter on the serial killer show, Dexter, for a year. I’m guessing much of what he was exposed to there inspired this screenplay.

Writer: Devon Graye

Details: 92 pages

If there’s an argument to be made against structure and screenwriting convention, “Allison Adams” is a script you’d file as evidence in the trial. It throws the conventional whodunnit out the window, adds some Fargo’esque wallpaper to the living room, then dives into the basement where guys like Thomas Harris, David Fincher, and Patrick Bateman are playing poker.

Before we even get to the script, I want to hammer this point home. I read a lot of “missing girls” screenplays. Heck, there’s a whole cottage industry of missing girls novels. It is one of the most oft-used setups in fiction. And it works because there’s nothing that triggers readers like a helpless girl being taken.

Now you’d think that the average writer would know, when there’s concept competition, you have to bring originality to the table or nobody’s going to give a shit about your script. The default setup for this concept = small town, girl goes missing, meet all the suspects.

And yet, most of what I read in this genre is right off the assembly line. While they all have their slight variations that the writers will tell you is what makes them “fresh takes,” the truth is they’re all the same.

Allison Adams is not only NOT an assembly line script. It was crafted in some 1970s Russian basement by a guy named Lukslava.

In a small town, a young girl named Allison Adams goes out to ride her bike and never makes it home. As the town comes together to try and find her, we meet several women, all of whom, strangely, are named Allison Adams.

Nurse Allison has a 5 year-old son who she’s struggling to take care of due to the immense stress of her job. 16 year-old Cheerleader Allison is preparing to lose her virginity to her dream boy, Michael. However, she secretly has a thing for a 40 year-old neighbor who she could swear flirts with her whenever they talk.

Next up is Diner Allison, whose been saving up to buy a boat and sail around the world when she turns 50, which is later this year. And finally there’s 68 year-old Hermit Allison, who stays within the confines of her house as she has a rare condition that makes it impossible to make choices.

The script bounces around to the four Allisons, who at first seem to have nothing to do with the disappearance. But then a creepy thin man straight out of a Stephen King novel starts showing up in their lives. He starts with Nurse Allison, arriving at her hospital with a bottle of orange liquid he claims is his blood-soaked urine. But when Nurse Allison goes to get the doctor, the creepy-as-F dude disappears.

Eventually, the Thin Man starts killing off the Allisons, and it’s a race from the understaffed local police force to stop them from taking each Allison down. But why is there this obsession with getting rid of Allisons in the first place? The answer lies in the fact that each Allison is way more complex than we know.

Reads like this usually go in a predictable pattern for me. At first, I love them. They start out so damn mysterious, like when you pour yourself a bowl of Fruity Pebbles and somehow a cocoa puff makes it in there. There are all these unanswered questions. And the creepy weirdness makes every page feel like the possibilities for the story are endless.

Then once the script hits the second act, the writer realizes the narrative needs to go somewhere, and the script struggles to keep its weirdness while introducing logic into the mix. Once the script hits the final act, and the writer has to actually wrap things up, everything falls apart as it’s exposed that the writer never had a plan in the first place. They wrote themselves into a corner of mysteries and bet on black they could write their way out. 99% time, they don’t make it out, dying an elongated death of screenwriting starvation, the last words typed on their screen a combination of an idea for a scene in the third act that involves a wheelchair, and half their grocery list.

So Allison Adams should be commended for being a member of the 1%. I’m not going to get into how Graye did this, as that would unleash massive Spoiloria. But we’ll just say this: He did it.

To those who like weirdness and hate Hollywood structure, Allison Adams is a reminder that you can be weird as long as you have a plan. Do not start writing a weird story with no idea where you’re going. I guarantee you, your script will be a mess. You don’t have to know your ending exactly. But you should have a good approximation of it.

How do I know Devon planned this whole story out ahead of time? Cause there were about 30 payoffs in the third act. That’s the easiest way to figure out if the writer had a plan. If they’re paying off things that happened on page 20, page 34, page 51, you know they had a plan all along. And the script is always better for it.

Writers who don’t have a plan overcompensate with the third act, injecting all this crazy wild stuff in the hopes that it will distract the reader from the fact that you ended up here just as cluelessly as they did. Crazy wild over-the-top stuff = made it up. Tons of payoffs = planned.

The script is not perfect, although these weird scripts rarely are. That’s the beauty of them. The big weakness is the character of Diner Allison. Whereas all the other Allisons had something weird going on, Diner Allison was just a good old girl with a dream.

Look.

If you’re going to go the non-traditional route of following multiple protagonists, that’s fine. But don’t just have multiple protagonists to have them. Make sure each of them merit their inclusion.

Because often what a writer will do is they’ll get this story point set in their head. In this case: “I’m going to have four Allisons.” And even though, five months down the road, one of those Allisons isn’t working, they’ve always been so set on having four Allisons that they’d rather keep the thing that’s not working than move off their original idea. You guys know what I’m talking about and you know what you have to do when this situation arises (if not, see “what I learned” below).

But other than that, this was a weird suspenseful ride that reminded me you can play with generic setups as long as you find a truly different way to explore them.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: KILL. YOUR. BABIES. OR. MAKE. THEM. ADULTS. No matter how much you love the idea of something in your script – a plot point, a scene, a character – If it’s not working, you have to kill it. Or, if you don’t want to kill it, you have to try something else to save it. Diner Allison is the weak link in this script. She either needed to be dropped or reimagined into something as interesting as the other characters. Making these choices is never easy. But if you ignore them, your script suffers for it.

A surprisingly kick-ass movie about friendship that was almost as fun to watch as the original!

Genre: Drama

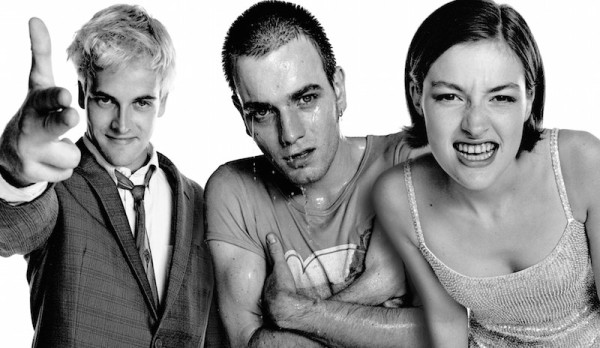

Premise: 20 years after Renton abandoned his heroin-junky friends for a drug-free existence, he comes back into town to try and make things right again.

About: The original Trainspotting launched the careers of director Danny Boyle and Ewan McGregor. But when Boyle went Hollywood, choosing Leonardo DiCaprio to star in The Beach after promising the role to McGregor, it destroyed the friendship instantly, which is the reason why it’s taken 20 years to make this film. Ironically, T2 is a film about mending broken friendships.

Writer: John Hodge (based on the novel by Irvine Welsh)

The original Trainspotting was part of a revolution in screenwriting and filmmaking that rocked the 90s. Writers and directors were sick of how studios had turned the business into a mathematical formula, and visionaries like Tarantino, Stone, Rodriquez and Boyle were more than eager to bulldoze that formula and erect an aggressive anti-structure in its stead.

Some say that’s the last time Hollywood took chances. After “indie” went mainstream, every potential product had to hit pre-determined checkmarks to get a green light. That’s changing, with Netflix giving directors huge budgets to do whatever they want.

But that hasn’t resulted in the kinds of voices we got back then. Even when a popular filmmaker does make some noise (Cary Fukunaga – Beasts of No Nation), a clear voice doesn’t come with it. In other words, I don’t think you’d know you were watching a Cary Fukanaga film unless someone told you you were.

That was the great thing about writing and directing in the 90s. People were trying to distinguish themselves and stand out. Let’s see if Boyle still has the desire to innovate, or if he’s simply been hit by the nostalgia bug.

When we last heard from Renton (Ewan McGregor), he’d ditched town to find a better life. Well, maybe he found that life and maybe he didn’t, but 20 years later, we see him flying back into town to give his best friend, Simon, the money he stole from him before he left.

Simon is attempting to turn his bar into an upscale brothel and asks Renton if he’ll help. Renton’s not interested but things are bad enough back home that he decides, what the fuck? I’ll stay for awhile. Renton also reconnects with his other best friend, Spud, just before Spud commits suicide. For 20 years, Spud still hasn’t kicked his heroin habit, and he’s ready for one final glorious high.

Renton convinces Spud to choose life, and recruits him to help on the brothel project. What they don’t know is that Begbie, who’s like a bar-hopping Scottish Hitler, as well as someone Renton fucked over 20 years ago, has just escaped prison. And when he finds out that Renton is back in town, he vows to find him and put him six feet under.

I’ll tell you what my big worry was going into Trainspotting 2. And it’s something that all screenwriters should be aware of. I thought Boyle was using this movie as an excuse to work with these actors again.

Why is that bad? Well, the best movies come when you’re passionate about telling a story. That’s how the original Trainspotting was born. Boyle read the book on a plane and he just had to make it his next film.

Once you start writing scripts for reasons other than wanting to tell an amazing story, that’s when you get in trouble. That’s not to say you can’t write something good unless you come at it that way. It’s just less likely to happen. And through the first 30 minutes, that’s what I thought had happened with T2. The over-reliance on nods to the previous film was the tip-off.

But then something happened. After we set up the rather convoluted plot, we were able to focus on these characters’ personal journeys as well as the film’s theme, and that’s where the movie began to shine.

You see, you may think that the reason the original Trainspotting is still relevant today is because it was flashy and bold and had a great soundtrack. But the reason Trainspotting lives on while similar flashy movies at the time (Natural Born Killers) have faded from memory, is because it had something to say about the world. Its theme was slammed into our faces throughout the film’s 2 hour running time: CHOOSE LIFE.

And Trainspotting 2 follows in those sprinting footsteps. Its theme is that while life takes you in different directions, and you get older and things don’t pan out the way you planned them, the one constant you always have is your friends. They’ll be there to pick you up. And that’s why Trainspotting 2 isn’t just another nostalgia trip. It actually has a reason for existing.

And if I’m going to leave you with anything to think about today, it would be that. The script you’re working on now? What are you trying to say with it? What do you hope people leave with when it’s over? If you’re just hoping they have a chuckle or that they enjoyed some cool action scenes, you’re not doing your job. If people want a fun ride, they can go to fucking Disney Land. They come to movies because they want to feel something.

And while I will always preach that entertainment comes first, if you want a story to stay with someone, you have to say something about the world, about people, or about our plight as a species in it.

The most powerful moment in this film was when Renton is asked, “What’s Choose Life?” The catch-phrase that became the marketing voice over for the original trailer. And Renton goes on a modern day “Choose Life” rant that resonates so hard, I found myself squirming in my seat (it’s much longer than in the trailer). You’re asking yourself, “Am I this person? And if I am, why the fuck am I allowing that to happen??”

I don’t know. I feel like writers are afraid to challenge audiences like that these days. Or when they do, they do it all wrong, like Moonlight or Machester by the Sea, where they bury their messages under layers of melodrama and overwrought unimaginative dialogue.

That was always the genius of Trainspotting: it could make you go from crying to laughing within a millisecond. They didn’t lose that here (don’t believe me? wait til you guys see the Spud suicide attempt).

I expected this movie to be a time-waster. It was more a wake-up call to remind me what good scripts are capable of.

[ ] What the hell did I just watch?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[x] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Passion comes through on the page. When you’re passionate about something, the reader feels it (and when you aren’t, THEY FEEL IT EVEN MORE!). For that reason, write about things you feel passionate about at this moment in your lives – passionate good, passionate bad – it doesn’t matter. As long as it’s gnawing at you, it will come through on the page. Trainspotting was constructed around this idea of mending broken friendships, which is what Boyle and McGregor had to do to work together again. And it’s for that reason that everything here feels so authentic and truthful. If these guys were just going down Memberberry Lane, this film would’ve sucked.

We’re back like a Shamrock milkshake, baby. For how long, I don’t know. So enjoy it while you can taste it!

To submit your script for Amateur Offerings, send a PDF of your script, along with the title, genre, logline, and finally, why your script deserves a shot, to: Carsonreeves3@gmail.com. Remember that your script will be posted. If you’re nervous about the ramifications of a bad review, feel free to use an alias name and/or script title. It’s a good idea to resubmit every few weeks so your submission stays near the top.

The rules of Amateur Offerings are as such: Read as much of each entry as you can, then, in the comments section, vote for your favorite script. The script with the most votes gets reviewed next Friday. If that script is really good, there’s a chance the review will kick-start the writer’s career.

And with that, here are this weekend’s entries!

Title: Rift

Genre: Fantasy

Logline: A team of Victorian monster hunters must save the universe from their biggest threat yet, themselves.

Why You Should Read: I’m a Benihana chef, mandolin player and a broke as a joke screenwriter living in LA now for two months shy of a year and I’ve written about 10 screenplays. I’ve got about thirty dollars in my bank account so there’s not much there to submit this screenplay to a formal contest which sucks, but I’m living the dream…which is cool. It would be very helpful if you would review it so I could know if I was heading in the right direction and if my diet of peanut butter jelly sandwiches in front of my computer monitor is paying off.

Title: The Keepers of the Cup

Genre: Action/Comedy

Premise: Two die-hard New York Rangers hockey fans steal back the Stanley Cup from vengeful Russian terrorists and travel across the country to deliver it in time for Game 7.

Why You Should Read: When you read this, I can promise you one of two reactions: either you will laugh and enjoy the ride, or you will find this a big swing-and-miss — such is life as a writer. Oh, if it helps, I graduated from USC’s screenwriting program, was named a finalist for Universal Pictures’ Emerging Writers Fellowship for this script, and was mentored by the writers of “Top Gun” and the famous unproduced screenplay “Smoke and Mirrors.” I can also bench 250 and avoid my mother’s phone calls. Honestly, who cares? An entertaining story is an entertaining story. I hope you enjoy “Keepers.”

Title: All Rise

Genre: Thriller

Logline: ALL RISE follows a reprobate judge sentenced to a prison populated with convicts whose lives he’s destroyed.

Why You Should Read: I won the FinalDraft Screenwriting ages ago with a script called “8Track”. My writing partner – Gary Waid – did 8 horrible years in prison for smuggling 19 tons of marijuana. We were both involved with an international smuggling ring. Meanwhile, Gary and I wrote a script a few years ago entitled “Goliath”, sent out by UTA. It’s now a novel, selling at Barnes and Noble and around the world. Great reviews from best-seller authors (including Frederick Forsyth) as well as a covered STARRED review from Publisher’s Weekly. We have another novel coming out in June. “GITMO” is also adapted from my original screenplay which was sent out by APA. Edel Rodriguez is designing the cover this week. Google EDEL RODRIGUEZ NEWS, it’ll blow you away.

Title: Beyond The Front Lines

Genre: Action-Adventure

Logline: Two American spies pose as Nazi Officers to track a German train from the Belgian Congo to Germany’s border in order to discover the whereabouts of Hitler’s secret nuclear program and destroy it before the Nazi’s most notorious female Officer, Belinda “the beast of Berlin” Von Halder discovers their plot.

Why You Should Read: The best way to describe this script is Butch Cassidy and The Sundance Kid meets Indiana Jones. Like those two films, the script is funny at times but also gives way to some great action-packed sequences. I’ve always wanted to write a WW2 script, but every attempt got bogged down in needless details and maintaining historical accuracies; which always led me back to writing Sci-Fi. So I decided, “to hell with it,” I’ll just write a fictional story, one that would address a very simple theme; a single question to be precise. Does the end justify the means? Will our heroes, US spies, shoot at US soldiers to continue their mission? Will they sacrifice one another if it means “Mission accomplished”? Will they overlook the atrocities of this war and press forward to their destination? I hope you’ll consider reading and I look forward to the feedback… Good Luck.

Title: Stand Tall!

Genre: romantic comedy

Logline: A Vegas waitress, made 16 feet tall, falls in love with the scientist who accidentally enlarged her. She sacrifices her size and fame to save him when he’s kidnapped by a blackmailing mobster.

Why You Should Read: I’m a journalist-screenwriter, a fan of romantic comedy and classic Hollywood. I’ve run the site Carole & Co., named for my all-time favorite actress Carole Lombard, for nearly a decade. “Stand Tall!” blends romcom and sci-fi in a retro yet feminist fashion, with vivid, fun characters — as our oversized heroine says, she would “rather entertain people than attack them.”