Genre: True Story

Premise: (from Black List) After losing his luster and respect in Hollywood, famed director Sam Peckinpah hopes to direct his next great film with financial backing from Colombian drug lords and brings along a novice screenwriter to write the film in Colombia.

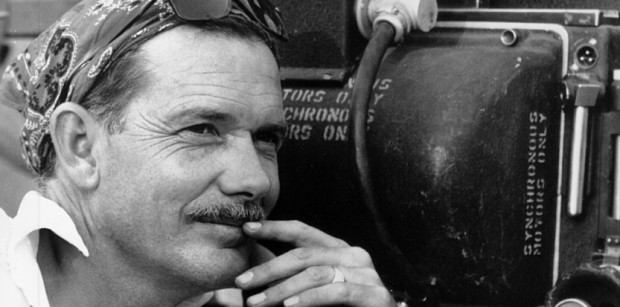

About: “If They Move Kill’em” landed on the 2012 Black List and was Kel Symons breakthrough screenplay. For those who don’t know, the subject of the script, Sam Peckinpah, was one of the best directors of the late 60s and early 70s, responsible for such classics as The Wild Bunch, The Getaway, and Straw Dogs. He was also a notorious addict who burned the candle at both ends AND in the middle.

Writer: Kel Symons

Details: 96 pages – 1st draft

Sam Peckinpah was the anti-establishment writer-director of his time. He hated… well, pretty much everything besides making movies. And to be involved in one of his films was like riding on a rollercoaster built entirely out of razor blades. While it may not have been enjoyable to be a part of the Sam Peckinpah legacy, you sure as hell came away with a lot of stories.

“If They Move Kill’em” is constructed around this conceit. It’s 1978, which was long after the apex of Peckinpah’s career. The Wild Bunch, his most famous film, was a decade old at this point. And while previous studio regimes had a “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” approach to substance abuse, movies were becoming big business, and that meant more scrutiny at every level. Heck, Star Wars had just come out a year earlier. Everyone was starting to see what movies could become. Which made Peckinpah a relic of the old guard.

This is perhaps why Peckinpah decided to make his next movie in Columbia using 100% drug money. Peckinpah’s drug-fueled logic was this: Sure, I might be using blood-soaked hundred dollar bills to make entertainment, but at least I don’t have to answer to a bunch of self-serving liars in suits hell-bent on destroying my vision. The Columbians loved his Westerns. They’d let him do whatever he wanted.

There was only one problem. Peckinpah wasn’t making a Western. He was a making a commentary about the Columbian drug-trade, something he didn’t necessarily mention when all of the “financing” was being put in place. Therefore, when he flies down to Columbia to finalize the details, his drug-lord handlers are none too thrilled about this surprising turn of events.

Meanwhile, Peckinpah has hired a neophyte screenwriter, Charlie Stetler, to write his film. Charlie, a straight arrow with an 8 months pregnant wife, isn’t prepared for the world he’s dropped into. This is a man whose most exciting daily event is when the coffee machine breaks at the community college he teaches at. Now he’s walking through metal detectors with suitcases full of half-a-million dollars.

Peckinpah uses a steady diet of gin and tonics, whiskey, and Columbian coke to fuel the prep for his film. But when the Madero brothers, his financiers, learn that Peckinpah isn’t giving them the next Wild Bunch, they go apeshit and consider killing off the prick and his sidecar screenwriting act.

What scares the shit out of Charlie is that Peckinpah isn’t worried about this one bit! He’d rather challenge random drug lords to arm-wrestling matches than figure out a way to escape back to America before they get a bullet to the head. That’s when Charlie considers the unthinkable. Maybe this was all part of the plan. Maybe Peckinpah came down here to end his life in one final blaze of glory. And poor Charlie is just collateral damage.

Boy, this started out great. Peckinpah is one hell of a character. He is a feeding frenzy of drugs, alcohol, and women. He is a raging lunatic, a hurricane looking to sweep anything within a one mile radius into his circle of pain and loathing. And for that reason, whenever we’re highlighting Sam, the script works.

Where “If They Move Kill’em” runs into problems is in its plotting, as it never seems like Symons has much of a plan here. It’s almost like he’s hoping once we land in Columbia, the movie will write itself. In his defense, it would seem that way. He’s got this great character in this volatile setting. Why wouldn’t the script write itself?

Welcome to screenwriting. Where IT’S NEVER FUCKING EASY. Even when you think it’s going to be easy, it’s not easy. I can’t tell you how many times I’ve thought to myself, “Well, at least I have that one scene coming up. That scene is going to be amazing.” Then I get there and realize it’s the hardest scene in the script to write.

What “Shoot’em” reminded me of is that you still have to outline. You still have to plot. You still have to structure. Because if you don’t, your story just sort of drifts. It may drift into some interesting places. But it’s still drifting. The reason you plot is so your story can build – so that it moves towards an identifiable climax, something we can look forward to.

That’s the problem here. Where are we moving towards? Are we moving towards an agreement to make the movie? Is that the main character’s goal? We’re certainly not moving towards the completion of production, since 3/4 of the way into the script, we’re nowhere near shooting a frame of film. So the audience is asking, “What’s the end game here?”

How this hurts you is simple. You don’t know where you’re going so you just start writing shit down hoping for the best. About 70 pages in, for example, Sam and Charlie are sent off to a cocaine processing plant while the Madero brothers figure out what to do with them. And then we just watch our characters hang out.

You’re 3/4 of the way into your movie. Your characters shouldn’t just be “hanging out.” With 30 pages left in your script, we need to be building towards something. Especially when you’ve made a promise to the audience by chronicling this insane main character.

A great example of doing this the right way is The Wolf of Wall Street. That film has a clear structure. We see the rise of Jordan Belforte. Then we see the fall. We always know where we are. And, more importantly, we’re always MOVING. We’re never just sitting around waiting for things to happen. That’s the death knell of any screenplay. If your characters are waiting for anything for longer than a scene? You need to rewrite that section of the script.

Yet I wouldn’t give up on this project. Peckinpah is a person who’s worthy of being written about. He’s built for biopicing. I could see every actor between 50-60 dying to play him. Bryan Cranston would probably be the way to go. Maybe even Pitt. But this script is a reminder that a character isn’t enough. It’s a superb starting place. But you still need a plot with a plan. And I never saw that here.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: The “innocent” thrown into the lion’s den is a great trope. Shonda Rhimes has built an entire TV empire around this setup. Remember that you’re always looking for conflict and contrast in storytelling. If someone’s in an environment they’re familiar with and/or comfortable in, that’s boring. But throw them into a world that they despise or are scared of, now you’ve got a movie. Peckinpah going to Columbia wouldn’t have been enough. He’s just as crazy as his hosts. But Charlie, the sweet and innocent screenwriter with a heart of gold being thrown into Columbia? Now you’ve got a movie. To test this, write a scene where a scheming drug addict walks into a strip club. I guarantee it will suck. Now write a scene where a bible salesman is dragged into a strip club. Watch the scene come alive.

Congratulations to Dean B for the big win this weekend with his short script, ASS LOLS (rhymes with “Assholes”), about an Adam Sandler pitch gone bad. Or good! He wins a free First 10 pages Consultation with me. Stay tuned as I’m anticipating this upcoming weekend’s Miniature Short Script Contest to be the best yet!

Genre: Science Fiction

Premise: An aging American working as a United Nations worker in Bucharest learns that his building is a front to hide a porthole that leads to another world, identical to our own.

About: Today’s pilot script comes from Justin Marks (The Jungle Book), a writer who’s built his brand on big ideas, allowing him to move into those high-paying mainstream screenwriting jobs that buy houses up in hills. Marks introduces the Starz network (Power, The Girlfriend Experience, American Gods) to their first science-fiction show. The project was flashy enough to nab Oscar winning actor, JK Simmons, for the lead.

Writer: Justin Marks

Details: 53 pages (2015 draft)

Every time they do the Oscar thing here in Hollywood, they close down all the streets that are anywhere near the Oscars. Which would be fine by me… IF ONE OF THOSE STREETS WASN’T THE STREET THAT IN ’N OUT WAS ON!!! By closing down In ’N Out street, the Oscars closes down a porthole to happiness. And that isn’t acceptable. So if you see someone holding up a sign outside the red carpet this weekend that reads, “#OscarshatesInNOut, you’ll have a good idea who it is.

Meanwhile, we’re in pilot frenzy mode, with fresh pilots flying off screenwriters’s laptops every couple of minutes. As writers have accepted the reality that unless they write a biopic, Hollywood doesn’t give a shit about their stupid feature spec, they’ve come over to the side of the business that actually makes people money. Unless you’re Justin Marks of course, who, after this pilot airs, will be pulling down money from both sides.

Counterpart takes place in modern-day Romania and follows Howard Silk, a 50-something American who works at the Office of Interchange, which I believe is some sort of United Nations outlet. Doesn’t matter really. Howard’s job is as boring as it sounds. He walks into a government building every day, meets with a few people, writes a few things down, goes home, wash, rinse, repeat.

It’s gotten so fucking depressing that Howard begs his bosses for a promotion. But Howard is seen as a weakling, a nobody with zero people skills. As his boss puts it, “It’s been sixteen years, man. If it were going to happen? It would have happened.”

If that sounds bad, Howard’s personal life isn’t going much better. The love of his life, Emily, has been in a coma for six months after getting whacked by a motorcycle while crossing the street. Emily’s dickhead brother keeps flying to Bucharest to convince Howard to let the family have Emily back so they can pull the plug on her. And Howard is about to concede.

That’s when everything changes.

Howard comes to work one day to find that his normally dismissive boss needs him immediately. Howard’s placed in a room until another man enters. That man… is Howard. But this Howard seems bigger, stronger, more confident. One might say he’s everything Howard wishes he could be.

That’s when Howard’s hit with shocking news. This government faction he works for is a front to hide a porthole that connects our world with another one. This other world is similar to ours in almost every way, with tweaks here and there. For example, Howard is a lower level management nobody in our world, but a top level superstar agent in the other.

Howard 2 informs us that there’s an agent who’s crossed over to our side and is assassinating people. In order to capture this agent, Howard 2 will need to start operating in our world. As a byproduct of this, Howard 1 will need to be upgraded into a top-level agent in order to provide a believable cover for Howard 2’s involvement. This means that Howard will finally get that promotion he’s so desperately wanted.

But what does this mean for a man who’s spent his entire life being overlooked? Will he be able to convincingly portray this new persona? Or will it be a case of, be careful what you wish for?

Counterpart embraces some good old Scriptshadow principles, primarily that if you want to get actors interested, give them dual roles to play, with each role being the polar opposite of the other (JK Simmons gets to play a meek weakling and a badass boss, all in the same show!). This was smart move numero uno by Justin Marks.

Also, Marks is very aware that this is a television show and not a movie. For that reason, despite its flashy sci-fi core, Counterpart is about character. The pilot is more focused on the flaws in Howard’s character (he’s a weakling who doesn’t stick up for himself) than some expensive sci-fi plot with hover-bikes chasing aliens.

You always have to keep that in mind with television. It’s why they could make a big sci-fi idea like “V” twenty years ago. The producers knew that the “aliens” would be in human form 90% of the time, which meant no big-budget effects.

Think about it. Whenever you try and stretch science fiction or fantasy and you don’t have an HBO budget? It looks cheesy. Go watch any episode of Fox’s Minority Report or APB to see what I mean. So stuffing these high-concept sci-fi ideas inside of these low-budget delivery capsules is the secret sauce for coming up with a sci-fi show. Or, at least, one that has a chance of getting on the air and not embarrassing itself.

That’s not to say there’s no plot in Counterpart, however, or that there aren’t things happening. The things that are happening are just doable. So here, we have an assassin running around killing people. This is a best-of-both-worlds scenario because it’s a legitimate problem that provides a compelling plot. Yet, again, it costs nothing to implement.

On top of all of this, Counterpart is the rare science fiction idea that feels unique. No time travel. No robots. While the concept’s core is somewhat familiar (a parallel world), I’ve never seen it explored in this way before – a “Cold War” like conflict that occurs within a government agency. That’s what you’re always looking to do, guys. Take that familiar element and explore it in an unfamiliar way.

The only issue I had with the pilot was the third act, which was built around Howard 2 getting to see his wife again, even if just in coma form. In his world, his wife died four years ago from cancer. So this is a profound moment for him. But all I kept thinking was, “I don’t know Howard 2. Wouldn’t this work better if Howard 1’s wife had died of cancer four years ago and he got to cross over into Howard 2’s world and see her again, alive?” It would’ve been a lot more emotional since we know Howard. Who cares if Stud Howard gets some time to see his wife again? His life fucking rocks regardless.

But I suppose it’s a minor nitpick. Also, there’s a twist at the very end that changes some of that. All in all, this was both a smart idea and a smart way to circumvent the low-budget requirements of television. I still don’t know if anyone watches Starz. But maybe they will once Counterpart airs.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: If you’re interested in high concept material, make sure you consider your idea’s “delivery capsule” before you start writing. A delivery capsule is everything the audience will see onscreen. If you have period piece settings and monsters and swords and sandals and tons of characters and locations, a la Game of Thrones, you only have a couple of places to pitch to (HBO and Netflix). But if your delivery capsule is modern day Bucharest with zero special effects, you can pitch that to any network on television, which increases your chance for a sale.

Last week, one of the greatest moments in Scriptshadow history occurred. If you missed it, we introduced….

THE FRIDAY SHORT SCREENPLAY MINI-COMPETITION (a.k.a. “Making screenwriting great again”)

The contest took the world by storm, with every major media outlet weighing in on it. Here are some of the reactions from that historic day:

Anderson Cooper: “Who is this man? This man who has changed the landscape of screenwriting in a single day?”

Megyn Kelly: “The world may be falling apart. But Scriptshadow continues to bring people together.”

Brian Williams: “While other screenwriting sites continue to engage with Russia, Scriptshadow demonstrates how to be a true American hero.”

To remind those of you who’ve forgotten how I changed the course of history, last week I had a weekend short script competition whereby the only rule was that you had to use TWO of my “Best Bang For Your Buck” screenwriting tools, which I had written an article about the previous day.

Well, we’re doing the same thing today. The only difference is that you have to use two of the five NEW “Best Bang For Your Buck” tools that I wrote about yesterday. For those who are too lazy to click the link, those tools are…

1) A character who wants something.

2) Suspense.

3) The magic of an unresolved issue.

4) Things don’t go according to plan.

5) High stakes for every character.

Post your short in the comments (you can write it inside the comment or include a PDF link). Page count is open but I recommend staying under 5 pages. Whichever short gets the most up-votes by Sunday 10pm Pacific Time will be the winner, and receive a FREE FIRST 10 PAGES consultation on any feature or pilot you’re working on.

Also, for those who’ve forgotten, we have a much bigger OFFICIAL SHORT SCREENPLAY COMPETITION coming up. You still have about a month until the deadline. And with that competition, Scriptshadow will be producing the winning short film, which will debut here on the site. So consider this a chance to practice.

Get to work and good luck!

NOTE: MAKE SURE TO SORT COMMENTS BY “NEWEST” SO YOU CAN SEE ALL THE NEW SHORTS THAT COME IN.

Last week we took five effortless screenwriting methods known for their power to improve a screenplay and then we had a competition the next day challenging you guys to implement those methods into a short script. The experience was so fun, I decided to do it again!

So here are five MORE bang-for-your-buck methods you can use to improve your scripts. They’re a little more involved, but no less helpful. Also, don’t include any short scripts in the comments today. That’s for tomorrow. Here we go!

NUMBER 5 – A CHARACTER WHO WANTS SOMETHING

One of the easiest ways to give your story life is to give each and every character SOMETHING THEY WANT. The more concrete the want, the more defined the character (a character who wants a bag of money, like Anton Chigurh in No Country For Old Men, is preferable to a character who wants “a better life” which is vague and nebulous). The main reason you want a character to want something is that it INSTANTLY MAKES THEM ACTIVE. They now have to go and get it. And if a character is trying to get something, they’re moving. And when they’re moving, the story’s moving. But the real power of this tool is when you apply it to not just your hero, but to all your characters. Because then those wants start colliding, and that leads to conflict. And conflict is the essence of great drama. Needless to say, this is really important.

NUMBER 4 – SUSPENSE

My last post on this topic confused, frustrated, and in some cases, angered readers. So I’ll try to keep today’s definition of suspense simple. Introduce something that the audience wants a resolution to, then suspend the reveal of that resolution. This was the basis behind Nick Morris’s winning short script from last week. He introduced a mysterious box, then waited until the very end of the story to open the box. Suspense tends to work best when the hero is in some sort of danger. When Clarice Starling comes to Buffallo Bill’s house at the end of Silence of the Lambs, we know that Buffallo Bill is the killer. But she does not. The writer then draawwwwws out the reveal, making us suffer through the scene, before Clarice eventually figures it out. If Clarice would’ve walked in, seen evil in Buffallo Bill’s eyes immediately, then pulled out her gun and started shooting, how fun would that have been? But suspense can be used anywhere. A guy and a girl who have tons of chemistry meet at a party, and then we suspend the moment until their first kiss.

NUMBER 3 – THE MAGIC OF AN UNRESOLVED ISSUE

Wanna improve your dialogue immediately? Give a character something they’re upset about with another character, but they haven’t brought it up yet. The tension resulting from that unresolved issue will play as subtext underneath any dialogue between those two characters. The most obvious version of this is that a woman has just found out that her husband is cheating on her. Her husband, meanwhile, comes home oblivious. He kisses his wife and asks about her day. Meanwhile, the wife is stewing, and we make our way through this conversation with this huge elephant hovering underneath it. But you don’t have to use this tool with one character ignorant of the situation. Another version of this is two parents who have lost a child but they never talked about it. So that unresolved issue is playing underneath even the most mundane of their conversations. This is essentially the essence of subtext.

NUMBER 2 – THINGS DON’T GO ACCORDING TO PLAN

Nothing should ever go according to plan in movies. If your character goes to the DMV to get a new license, goes into his boss’s office to ask for a raise, goes to the store to buy some groceries, or goes to an asteroid to stop it from colliding with earth, THE EVENTS THAT UNFOLD WHEN HE GETS THERE SHOULD NEVER GO ACCORDING TO PLAN. Some might say that storytelling is just a series of events that don’t go according to plan.

Why is this important? Well, let’s say a character wants to ask for a 100k raise from his boss. He goes in, asks for it, and gets it. Was that interesting to watch? Of course not! It’s fucking boring! But if he goes in having practiced his “raise speech” all night long, then, just as he’s about to ask, his boss brings a second person into the meeting and informs our hero that he’s being let go from the company and that, for the next two weeks, he’ll be training his replacement, now you have a scene. Where this tool becomes really powerful though is when you build the plan up beforehand. Make it so our character or characters have practiced and prepared for this event endlessly. The best example of this is heist movies. The characters spend the whole movie preparing for the heist, making sure they have every angle covered. And then, of course, none of it goes according to plan. The fun is in watching your characters react to this. It’s the power of plan disruption.

NUMBER 1 – HIGH STAKES FOR EVERY CHARACTER

I recently read a script that involved a giant party scene. Everything in the story was leading up to this party. However, when the party finally arrived, it was DOA. It just wasn’t that interesting. And the writer wanted to know why. The answer was simple. Not enough characters had something at stake in the party. They were just there to have fun. For a big scene to work, but really, for any scene to work, each character in the scene needs to have something at stake. If the moment goes poorly, they stand to lose something. If the moment goes well, they stand to gain something. If those principles aren’t in place, the audience isn’t going to care what happens.

For example, I was watching this old movie “Marty,” last week about an aging unattractive bachelor who’s just about given up on trying to find a wife. But his mother begs him to please go to a local club and try to talk to someone. Marty’s been to this club before and it’s only ever resulted in rejection. So he doesn’t want to go. But he doesn’t want to upset his mom either. So he relents.

This is the PERFECT scenario to show how impactful stakes are. We know that this is literally the last time Marty will ever try to find a girl. So this moment HAS to go well. And for that reason, the scene is great. Had the writer constructed the scene so that Marty goes to this ball every week and this is just part of his routine, the scene, like the party scene in the amateur script I mentioned, would’ve been DOA. Nothing’s at stake if he’s going to be here next week doing the same thing.

But here’s the real power in this tip. The writer didn’t just pay attention to Marty in regards to stakes. The girl Marty approaches is struggling with the same problem. She too has just about given up on trying to find someone. So going out is a big deal for her as well. The concept is this: The more people in the scene who have something at stake in what happens, the more charged the scene is going to be. Start with your hero. Make sure he has something at stake. But then move to the other characters as well.

One of this generation’s greatest screenwriters hits us with a new TV show on HBO. Does he deliver??

Genre: TV Pilot – Drama

Premise: “Here, Now” takes a Portland-based Brangelina-type family – a trio of multicultural adopted children – and asks how they approach life once they’re all grown up.

About: HBO’s golden child and Emmy award-winner Alan Ball (True Blood, Six Feet Under), who is also an Oscar winner (American Beauty) is finally bringing a new show to the network. But the family drama space is getting crowded. With smart well-written hits like Hulu’s “Casual” and NBC’s “This is Us,” can Ball still stand out in the space he pioneered?

Writer: Alan Ball

Details: 61 pages

Back in the late 90s, the game changed for spec scripts.

What happened was that, for the first time, people in Hollywood started utilizing chat-rooms to discuss screenplays.

The reason this was a game-changer was because, up until this point, the people who controlled Hollywood’s opinions on screenplays were agents.

As a writer came close to finishing a script, his agent would hype the script up to producers and studios. By the time it was ready to go out, a bunch of interested buyers were eagerly waving their checkbooks.

The pressure became so intense to get the new hottest thing that studios would make bids on scripts that they hadn’t even finished reading, just to beat the other guy. A great concept and a good first act could result in a high six figure sale.

When the chat rooms came around, however, the gig was up. Assistants would get on these digital information-sharing networks and they would blow through the hype. If a script was bad, this secret cabal would expose it.

Hollywood was never the same after that. You couldn’t bullshit anyone anymore. You actually had to write something good. And what these chat rooms exposed was the fact that mostly everything wasn’t good. Without hype to distort opinions, you’d be lucky to get a, “Eh, it wasn’t terrible.”

This new reality continued for a couple of years until one script arrived that blew all these impossible-to-please readers away. That script was American Beauty, by an unknown writer at the time named Alan Ball.

Every reader came back with the same reaction: BRILLIANT!

And that’s how American Beauty became the poster child for writing scripts in the internet age. No more bullshit. If you want to sell something, it needs to be good.

This is why, when Alan Ball writes something, everyone in town wants to read it. And I’m no different. I’m a monster fan. If I could only invite five screenwriters throughout history to a dinner party, Ball would be on that list.

So to say my expectations are high today would be an understatement. However, I have a funny feeling that Ball will meet them.

26 year-old Duc (pronounced “Duke”) is a life coach and member of a very odd family. Audrey, the mother, and Greg, the father, took the Brangelina route of building a clan. They adopted kids from all over the globe.

There’s Duc, who’s Vietnamese. There’s Ramon, who’s from South America. And there’s Ashley, who’s African. Completing the family is 15 year-old Kristin, a self-proclaimed pudgy pasty white girl who’s not nearly as hot as she wants to be. Kristin was an unexpected addition, the only biological child in the family, making her, ironically, the black sheep.

The plot for the pilot is built around Greg’s 60th birthday party. Greg, who fucks a Japanese escort every week, can’t handle how quickly life has gone by. And he doesn’t want to be reminded of it with some giant birthday bash.

But his problems aren’t as bad as Ramon’s. Ramon has enjoyed being a sexually adventurous gay man for the last few years of his life when he starts seeing the numbers “11:11” everywhere. At first he thinks nothing of it, but they appear so frequently (we watch as his treadmill inexplicably gets stuck on 11:11 for a full 30 seconds) that he’s starting to think something is wrong.

Meanwhile Ashley, who’s happily married (to the ideal white man), is secretly a coke-fiend who loves to play as close to the fire as she can get without getting burned. Case in point, she’s found a new boy-toy in 18 year-old Randy, a male model. She convinces him to join her at Dad’s party tonight, with the caveat being that he can’t tell her husband that she invited him.

Once the party gets started, everyone lets loose. Kristin, who’s decided it will be funny to wear a horse-head the entire night, takes a liking to Randy. Ramon brings home a coffee barista he’s been flirting with, and the two promptly sneak away to have sex. Greg is trying not to have a mental breakdown and, with a little alcohol, seems to be in better spirits.

But everything unexpectedly goes to hell when Ramon’s 11:11 vision takes a turn for the worse. So much so, that it will change his, and his family’s, life forever.

If you want to get better at creating rich interesting characters who pop off the page, there’s no one better to study than Alan Ball.

Ball knows that if we don’t feel the characters on the page, or on the screen, we won’t care what the fuck happens to them. And the thing is, he’s so focused on that, that he barely needs any plot to tell his story. Every single person here is so fascinating that THEY become the story.

It’s in stark contrast to yesterday’s script, which was so plot heavy that all the characters got lost in the muck. It’s a great reminder that proper character creation allows you to be less plot-focused. And since plotting’s always a bitch, that’s a huge advantage.

One of the nice lessons I learned with today’s script comes from something we were just discussing last week – SETUPS AND PAYOFFS.

Normally, setups and payoffs are done through plot. But Ball reminds us that you can utilize them through character as well.

The best example of this comes from Kristin, the 15 year old biological daughter in the family. Kristin hates how she looks so much that she creates fake Facebook profiles with pictures of beautiful women, just so she can get attention from men somehow. Kristin desperately wants someone but believes nobody would want her.

So later, during the party, when Kristin is wearing her horse mask, she runs into a dejected Randy, the model, who’s since been rebuked by Ashley, Kristin’s older sister. Kristin’s character has been so well set up at this point, that before she’s even approached Randy, we’re freaking the hell out, saying, “Oh shit oh shit! She’s going to get the model! She’s going to get the model!”

The ensuing interaction is one of those script moments that, without proper setup, would’ve come off as mundane. Instead, it’s a highlight.

This is the power of Alan Ball. He gets it. He has such a strength for taking potentially boring ubiquitous things – like Greg’s fear of getting old – and creating powerful characters to explore those things, that we feel like we’re dealing with it for the first time.

Here, Now is a pilot that achieved something unthinkable to someone who reads everything. It made me feel something. It made me think. It actually has something to say about the world and people and how we experience life. It’s quite the pilot and definitely lived up to expectations.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[x] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: When you write a TV pilot, really really really focus on character. People have to see your characters and say, “I want to spend time with these people every week.” If your characters are in any way bland or even “just above average,” we’ll have no interest in your show. So here are three suggestions to get you started in this department.

1) Give each character a great description. Don’t worry if it’s a little long. Again, characters matter more in television so the rules in regards to describing them can bend a bit. Here’s a description of a character in Here, Now: “Barista HENRY BERGEN (20) is behind the counter in BLACK PANTS, WHITE SHIRT and some sort of VEST with a NAME TAG. Beard, tattoos. Cocky, handsome, gravitates toward a simpler existence. Doesn’t need much, appreciates what he has.”

2) Within the limitations of your story, introduce each character with a memorable action that defines who they are. I see too many passive character introductions in screenplays. Within the context of the scene, make me interested in your character when I meet them. When we meet Ashley, she is berating an employee for an action that cost her company a huge chunk of time. It immediately sets the tone for the character.

3) Give your characters MOMENTS they shine in the areas they shine in. So if you have a character with a wicked tongue, give her a scene where a department store cashier shames her and she retaliates by telling her off in some clever way. If all you’re doing is serving the plot and not giving your characters these moments, they’re going to disappear on the page.

Bonus Question: Who would be the five screenwriters throughout time that you would invite to your dinner party?