Genre: Biopic

Premise: Thomas Edison and George Westinghouse battle it out to light the Chicago World’s Fair. The winner will end up lighting America.

About: Graham Moore burst onto the scene when he wrote The Imitation Game, a script that snagged the top spot on the Black List and then went on to surprising box office success. Moore would eventually win the Oscar for best adapted screenplay. The scribe, an admitted history junkie, did double duty this time around. He wrote a book about Edison and Westinghouse, then adapted it himself. The film will reteam Moore with Benedict Cumberbatch, who will play the prickly Thomas Edison, and director Morten Tyldum. The film will also star Eddie Redmayne as the main character in lawyer, Paul Cravath. (edit, oops! I got these two projects mixed up. Cumberbatch is appearing in The Current War. My fault!)

Writer: Graham Moore

Details: 134 pages

While everybody’s worked up about the upcoming Oscars, I’ve already moved on to next year’s Oscars! And today, we have what will surely be a major contender in the top categories.

Moore finds himself in a very enviable position. He’s a screenwriter who loves biopics living in the golden age of biopics. Outside of a couple of names (Aaron Sorkin comes to mind), there isn’t anyone better than him at it. And he’s proven that again, today.

26 year old Paul Cravath was only in law school two short years ago. Now he’s been tasked with telling one of his firm’s biggest clients, George Westinghouse, to give up his bid for lighting Chicago’s World Fair.

It’s 1888, a time when electricity is just starting to make its way into cities. Everyone knows that whoever can win this war will be rich beyond comprehension. The person leading the pack is Thomas Edison, who’s created a functional, if sloppy, light bulb.

George Westinghouse, on the other hand, has created a light bulb with the kind of warm dreamlike glow that leaves you feeling all fuzzy inside. The problem is that Edison came up with his bulb first. And he’s suing Westinghouse on a number of fronts to make sure he can’t light the fair.

Now that doesn’t sound fair, does it?

Westinghouse, against the advice of the firm, employs Paul Cravath to fight Edison tooth and nail. There has to be a flaw in his patent that will allow Westinghouse to win this battle. The problem is that Paul doesn’t have enough manpower to fight someone as big as Edison. There aren’t enough hours in the day.

So Paul invents the first ever hierarchal legal research system, employing associate attorneys who can do the medial work for him so he can focus on the big picture. Ironically, this system is as inventive as the light bulb, as it would become the operating foundation for every working law firm today.

But will that be enough to take out Edison? Only one way to find out.

I always find it interesting where a writer places his point of view. I mean, you have Thomas Edison. You have George Westinghouse. They are the “big picture” characters here. Yet Moore chooses to tell his story from a lawyer’s point of view. Was that a smart move?

Well, the core component of all drama is conflict. Where the conflict lies is where the entertainment is going to be. So Moore asked, where do these two titans meet? They meet at the point of this patent. And wherever there’s a patent battle, there’s a lawyer.

I probably wouldn’t have done this myself because when I think “lawyer,” I think “boring.” Especially a patent lawyer. But Moore treats his lawyer much like Tom Cruise’s part in A Few Good Men (not surprisingly, an Aaron Sorkin creation), where he plans to get Edison in court and force him to admit he cheated on the patent.

And that’s all well and good. But what I like about Moore is he has the ability to surprise you in a genre that’s plagued by its plainness.

Halfway into the story (spoilers), Westinghouse loses the patent battle to Edison. That’s right, HE LOSES. Not only is this a great plot beat (we’ve lost the battle with half the script remaining. Everyone’s asking, where do we go now??), but it allows Moore to introduce a third character.

Nikolas Tesla.

And I will tell you right now. Whoever plays this part is going to be a breakout star (unless he’s already a star). Moore goes so kooky with Tesla that you can’t look away from him. There’s a great little screenwriting tip here. Give a character a DEFINING ACTION, and if that action is strong enough, we’ll know exactly who that character is for the rest of the script. Moore focuses on Tesla’s “weird wave.” He keeps making this weird uncomfortable wave around people, and it perfectly embodied his oddness.

Tesla’s created a different kind of electricity that would not be bound by Edison’s patent. But Tesla’s a wild card. He’s got zero infrastructure. So Paul tells Westinghouse, who does have infrastructure, to team up with Tesla on his bid. The two become an unlikely pair with a common goal. Take out Edison.

Whenever you write biopics – hell, whenever you write a script – you need CHARACTERS. This is something it took me years to figure out. I was always a plot junkie. I thought fun stories, cool twists and great set pieces were the key to writing a great script.

But, in reality, it’s the characters. Because characters are interesting on their own. You can place a good character in a mediocre scene and we’ll still be drawn to him. Thomas Edison is a great character. He’s a fucking asshole. He’s full of himself. The man SUED HIS OWN SON! Whenever you put that guy in a scene, we pay attention.

Nikolas Tesla is a great character. He’s quirky, he’s weird, his mangled English leaves you scratching your head every time he speaks. The surprise element of Tesla makes him a fascinating character to watch as well. We never know what he’s going to do next.

Now here’s where the character argument gets interesting. Somebody in your script has to be the straight man. They’re the person who grounds the script. In most cases, this will be the hero. As a result, your hero ends up being the most challenging character to write. How do you make this person as interesting as an asshole, or a weirdo?

This is where a screenwriter earns his mettle. Because it isn’t easy. However, there are little things you can do to make us care. For starters, you can make your hero extremely determined. Audiences love determined people. You can make him an underdog. Audiences love rooting for the underdog.

Admittedly, these are “straight man interesting traits,” and therefore will never be as fun to watch as an outlandish part. But played right, we’ll be invested in the character’s journey. You can then use the orbiting characters to add a dose of spice to the story.

Of course, you don’t HAVE to make the main character the straight man. Alan Turing in The Imitation Game was offbeat. The same thing can be said for Jordan Belfort in The Wolf of Wall Street and John Nash in A Beautiful Mind. So it’s all a matter of whose story you’re telling and who’s point of view you want to tell it from.

As for the rest of the script, Moore includes some classic screenplay elements. We have a ticking time bomb – everything must be done before the World’s Fair. We have the “impossible task” (we’re told at the beginning that Edison’s lightbulb patent is one of the most airtight patents in history). We have that conflict I referred to. You can feel the weight of these two titans crashing down on the plot at all times.

The only problem I had with the script was the beginning. I didn’t understand why the heads of the firm were trying to get Westinghouse to pull out of a legal battle with Edison. Since when has a law firm ever turned away the money of its rich clients? That felt a bit forced to me.

But outside of that, this script was as bright as its subject matter. Moore has proven, once again, that he’s a hell of a screenwriter.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[x] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Make sure to remind your audience that your hero’s task is impossible. Hearing someone say, “Edison’s patent is the most airtight patent in history,” prefaces just how difficult the journey will be. Had this line not been written in, I wouldn’t have realized just how much of an uphill battle this was.

You got this one right, Scriptshadow Nation. What a script!

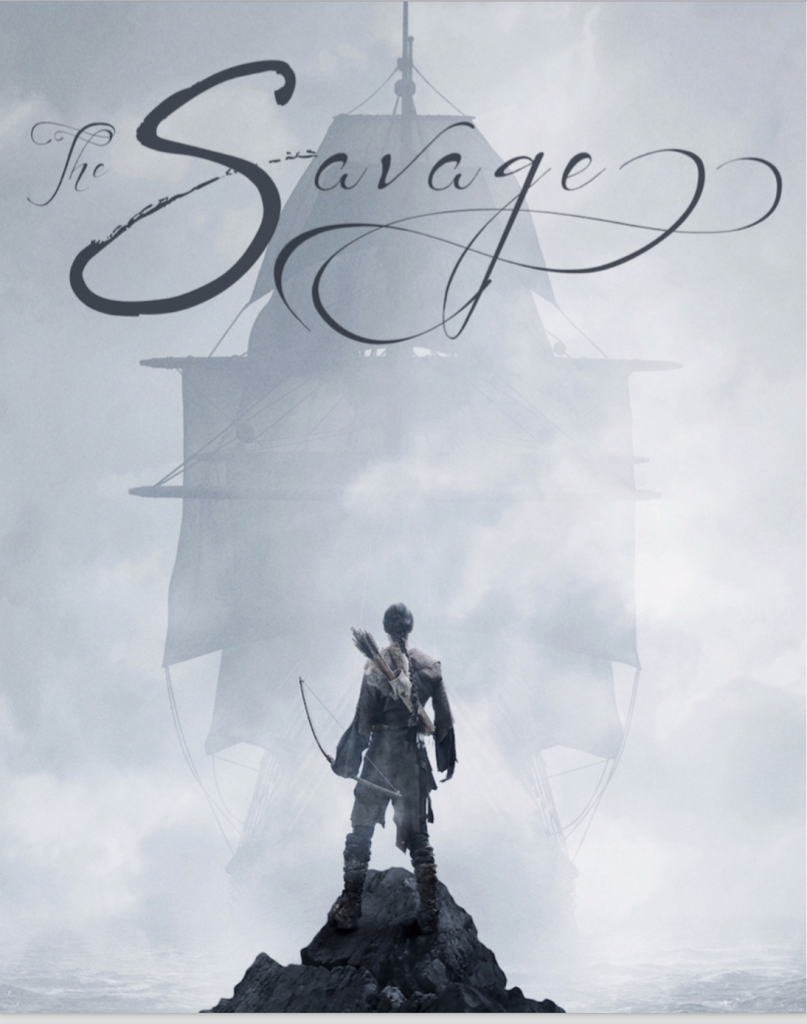

Genre: Historical Biography

Premise: The incredible true story behind one of America’s founding myths. After being kidnapped from his lands as a child, the Patuxet Indian Squanto spends his life fighting impossible odds to return home, setting in motion a series of events that changes the course of history.

About: The horse that led the race from start to finish, “The Savage.” Number 1 seed in The Scriptshadow Tournament, and now the champion!

Writer: Chris Ryan Yeazel

Details: 116 pages

Oh yeah.

Within a couple of pages I knew. I just knew why this won.

Within ten pages, The Savage had placed itself so far above the competition, I’m surprised any other scripts got votes against it.

More importantly, halfway through this script, I wasn’t even thinking about how it was the winner of the Scriptshadow Tournament. I was just lost in the story. I mean this is crazy! I’m not sure how true-to-history Chris’s adaptation was. But I never knew the story of Squanto. I know this though. Somebody needs to make this movie.

13 year old Native American, Squanto, a member of the Patuxet people, only wants one thing. To be a warrior. But when he’s stolen away by an Englishman sailing up the coast, every goal he’s ever known changes.

Squanto is whisked off to England, where he’s placed in the care of the eccentric governor, Ferdinando Gorges, a nobleman who funds the occasional trip to the Americas.

9 years later, and now fluent in English, Squanto hooks up with John Smith, he of Pocahontas fame. John is heading back to the Americas where he plans to establish a colony or two. He’s going to need a translator to deal with the natives, though. And Squanto looks like just the guy.

His payment for helping, Smith promises, will be to go back home. Thrilled, Squanto signs up. But Smith’s second in charge, Thomas Hunt, never trusts him. After taking care of business, Smith makes the mistake of allowing Hunt to escort Squanto home. And instead of delivering Squanto, Hunt kidnaps dozens of his people, takes them to Spain, and sells them off as slaves.

Forced to work the mines, Squanto eventually escapes with the help of some nearby monks. He becomes a monk himself, before finally heading back to England, where he gets a second shot to sail back home. It is there where he’s met with a truth so shocking, it will test him to his very core. Squanto will be forced to decide what life is worth, and if he can still contribute something good to a world that has only ever shown him cruelty.

The first thing I noticed about this script was the sophistication in the writing. Here’s a sample character description: “A gregarious, pompous ox of a man, Gorges does not speak so much as pontificate with operatic abandon.” That line doesn’t come from somebody who started screenwriting yesterday.

Something I commonly run into during reads is when the subject matter is above the writer’s current writing ability. They’re basically a 12 year old girl wearing mommy’s dress. No matter how hard they try, they don’t look like a grown woman.

This was the opposite of that. Everything from the action to the dialogue was so strong, I wasn’t even thinking about it. It was just doing its job telling the story. I mean, here’s a sample dialogue exchange.

That last line alone is heads and tails above anything I read in this tournament. The easy line would’ve been something like: “You sound just like the man that owns you.” And believe me, I see that kind of line often. To rearrange the words into a clever insult, then tie that to a zinger paying off an earlier reference – that kind of thing doesn’t just happen. It demonstrates a writer who’s dedicated and on his game.

And there were a lot of clues here as to the high level of writing. For example, there’s an early slow scene where 12 year old Squanto is sharing a moment with the girl he loves, Hurit. It’s this beautiful little moment between them. Then, just as it’s coming to a close, we see warriors running through the forest. One. Then two more. Then two more. We realize a giant ship has arrived at sea and they’re all going to check it out.

The takeaway here is that Chris didn’t linger on this scene. He knows that readers are impatient. If you’re going to slow things down, you want to follow that up with something flashy. But not just that. You want to camoflauge the moment by using the end of the current scene to transition into the following scene. So we’re not just going from slow to fast. We’re doing it seamlessly.

Chris also exploits the use of dramatic undercurrents. An undercurrent is anything that’s occurring underneath the surface level of the story that creates a sense of interest, curiosity, or dread. It’s a trick to double or triple up the reader’s interest level.

An example would be Thomas Hunt, the evil second-in-command on John Smith’s voyage. Every moment that Squanto and Smith share, you see Hunt nearby, clenching his teeth. He hates this savage. And we know that he’s going to do something about it at some point. And that’s where the undercurrent is happening. Until this conflict is resolved, it’s in our heads, keeping us curious. Keeping us TURNING THE PAGES.

Here’s my only beef with the script, even though I understand why Chris did it. The script doesn’t build throughout its second half. There isn’t this big giant goal that Squanto has to take care of, like, say, the last gladiator event in Gladiator. Or the wife being taken in The Last of the Mohicans. Squanto is basically trying to stay alive. And while that’s compelling, it prevents the story from building up, which is how most people like their stories told.

For example, when Squanto finally gets back from the mines, he learns that Thomas Hunt was killed a long time ago in a random altercation at sea. It would’ve been so much better had Hunt gone back to the Americas and set up a colony where he was in charge, and when Squanto got back home, he learned of this colony, and went to enact revenge on him.

Or, a big chunk of the story goes to Massasoit, the leader of Squanto’s rival tribe. Massasoit captures a young Squanto in the opening after Squanto steals something from him. Massasoit is pissed, but he basically laughs it off and lets Squanto go.

Then, in the end, our ending revolves around Massasoit once more, as he doesn’t like that Sqaunto has become chummy with the new English neighbors. The reason why this sequence didn’t carry a lot of weight was because Massasoit was never that bad. He was nice enough to let Squanto go in the beginning.

If this man would’ve been responsible for the eradication of Squanto’s tribe, now we have the potential for a lights out ending. If this man would’ve been the embodiment of evil, now we have an impending showdown that we’re looking forward to.

But we don’t get anything like that, and it keep the last 30 pages from building.

With that said, after reading the final pages, I understood historically and thematically why Chris did what he did. However, I wonder if there’s a version of this out there that could have that bigger satisfying ending yet still keep the essence of what Chris was trying to do.

Either way, this was a hell of a read. I mean, what a life this man lived. It’s incredible. And thank God someone as talented as Chris was responsible for telling us his story. He really did it justice.

Script link: The Savage

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[x] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Going back to the Thomas Hunt undercurrent conversation… In general, anything that’s unresolved is something that is captivating your reader. That’s why you want multiple unresolved threads in your story at all times. You can get that through unresolved conflicts between characters. You can get it through multiple unresolved plot goals. There’s no limit on how many pieces of your story can be unresolved. So take advantage of that. A lot of beginner writers only see the final goal as their unresolved thread. So a newbie writer would’ve gone with: “Squanto tries to get home” and that’s it. But that’s not enough to keep our interest. You need to add extra unresolved storylines to keep us engaged. If you think about it, this is the essence of drama. If it’s resolved and cozy, there’s no reason for the reader to worry. And if we’re not worried about anything, we’re probably bored.

Genre: Romantic Comedy

Premise: A heartbroken woman, employed to test men for fidelity by their concerned fiancées, finds her world turned upside down when she falls for her latest target.

About: I continue my reviews of the Top 4 scripts from the Scriptshadow Screenplay Tournament, a tournament that started with a challenge to write a script in three months, resulting in over 500 entries, which I then vetted into 40 scripts to compete in the official tournament. I then let the readers of the site vote on which scripts advanced through each round. Billie’s script here finished in SECOND PLACE. You can read the first two semifinalist reviews here and here. Stay tuned, cause tomorrow I review the winner!

Writer: Billie Bates (story by Michele Mathis & Billie Bates)

Details: 101 pages

When exactly did the romantic comedy die?

I’ll tell you. Because I know exactly when the last true romantic comedy hit occurred. It was 2009. The Proposal. And really, the rom-com was dead way before that. The Proposal was able to squeeze the last remaining juice from an orange that had been dry for a good 5 years.

It was four things that killed the rom-com. The first was Adam Sandler. He dumbed down romantic comedies to a level that they had never been dumbed down to before. And because his brand was so big, he sucked up any opportunities for other rom-coms to break out.

The second was the holiday-themed rom-coms (New Year’s, Mother’s Day, Christmas), which were less stories, and more a marketing gimmick to get a bunch of familiar rom-com faces together in order to get butts in seats. Gone were real concepts. Replaced by a holiday. While some hard-core rom-com lovers bought in. It was a white flag to the casual rom-com client. These movies screamed out, “We’re not trying anymore!”

Then there was Judd Apatow. Apatow found a way to give audiences a little bit of romance wrapped inside a meaty crunchy manosphere container. Once men got a taste of this, they refused to go back to the lighter fluffier rom-coms of old, even if their girlfriends begged them to.

This may seem like I’m burying rom-coms for good, but that’s not the case. Anybody who knows Hollywood knows that everything that’s old becomes new again. Remember the 90s when we were convinced there would never be a big Hollywood musical again? Not long after that, musicals hit a hot streak.

So I know romantic comedies are coming back at some point. The question is, in what form? Will it be the old school way? Or will someone find a clever new angle into the genre?

Michele does the kind of job that most girls would be scared to hire someone to do. She seduces your fiancé. The idea here is that if she can make him cheat, he was never right for you in the first place. In that sense, Michele’s doing a good thing.

Unfortunately, that “good thing” doesn’t pay the bills all the time. So Michele has to do side jobs to pay the rent. On her most recent job, she’s doing the make-up for a modeling shoot when she tells the buff photographer, Brad, that he’s being inappropriate with the models. Brad promptly tells her, “Ya fired.”

Down in the dumps, and down in the finances, Michele’s about to give up until she gets a new Cheat request. A bitchy young woman, Tanya, wants to make sure her fiancé won’t cheat on her. So after the forms are signed, Michele heads off to find her next victim, only to realize it’s… you guessed it, Brad!

The thing is, Brad doesn’t like Michele from the start, which means none of her trusty tricks work. But Michele’s no quitter. She puts everything she’s got into seducing Brad, even if 90% of it fails. Finally, he starts to come around. Which is great, right?? Not exactly. Because it turns out Michele is falling for him as well.

I’ve read four Billie Bates scripts now and I can proudly say that each one has gotten better than the last. The Bait is easily the best script of hers that I’ve read.

There’s a lot of good here. For example, the setup is strong. You have this woman who desperately needs money. She then gets a job where the only way she gets paid is if she succeeds. That stabilizes the stakes for the movie right there.

Then, her job is hampered by the fact that her target hates her. So as an audience membe we’re going, “Oh no. This is the worst possible guy she could’ve been assigned to.” So of course we want to keep watching to see if she can pull this off.

And Billie has one of the cleanest easiest-to-read writing styles on the site. It’s effortless to read through her scripts.

Here’s the thing though. The last reason the rom-com died was because it was the most formulaic genre of them all. And that formula proved to be impossible to break out of. Therefore, no matter how well you wrote a rom-com, it was still constrained by those plot beats that everybody already knew were coming.

And that’s how The Bait played out to me. I was always 30 pages ahead of the story. Which is why it’s imperative that you break formula as opposed to follow it. Because every beat a script hits that’s familiar is one more reason for the reader to start drifting. Why would they continue to pay attention if everything’s playing out exactly like they expect it to?

For example, of course Brad’s going to resist her at first. Of course he’s eventually going to like her. Of course she’s going to fall for him too. Of course she’s going to lose him. It’s a strange thing, screenwriting, because it’s begging you to follow it along the obvious path. That’s because the obvious path makes the most sense.

But the only reason for someone to keep reading a script is because the writer is ahead of you. They’re outthinking you as opposed to you outthinking them. And I didn’t see enough of the writer attempting to outthink me here.

I contend that the solution to bringing the rom-com back is doing something unique. Billie’s shown that she can hit the proper beats here. She’s followed the rules of this genre. Now she needs to write a rom-com where she breaks the rules. Where up is down and left is right. I honestly think it’s the only way to get any attention in these overly sterile genres.

And she can do it. She’s proven that she’s gotten better every time out.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: A screenplay is like a war between the writer and the reader. The reader comes into the war saying, “I know what you’re doing here. And it ain’t going to fool me.” The writer then says, “You know what? I know exactly what you think I’m going to do. So I’m going to do it differently.” Now the reader’s like, “Hmm, okay, you got me there. That just means I have to pay closer attention. But I’m still smarter than you.” And the writer’s like, “I know you think you’re smarter than me. That’s why I’m going to hit you with the exact opposite of what you thought was going to happen.” And so on and so forth. I’ll give you an example. The Break-Up. I never knew what the hell was going to happen in that movie because everything was reversed. Instead of the couple trying to get together, they were desperately trying to stay apart. The point is, you have to get into the reader’s head and ask what it is they expect to happen. You then need to continuously surprise them with your choices. That’s how you’ll win the war of expectation.

Genre: Period

Premise: With only one night to act, two rival soldiers must sneak behind enemy lines to complete a last-ditch suicide mission that will finally put an end to a decade-long conflict.

About: What Remains of Troy finished in the Top 4 of the Scriptshadow Screenplay Tournament, a tournament where the winner was voted on by the readers of the site. “Troy” was eliminated from the tournament early on, but given a second chance when readers voted it back into the main competition as a wild-card entry. It rode that wave to the semifinals, where it lost to rom-com, The Bait, which I’m reviewing tomorrow. You can also check out my thoughts on the first Top 4 script, Cratchit, which I reviewed yesterday.

Writer: Steffan DelPiano

Details: 100 pages

Usually when I see “ancient Greece” and “period piece” in the same submission I have nightmares of 204 page 12MB screenplays that take us through several centuries of Roman history, most of that history dialogue scenes in a garden. So when I saw this script clocking in at a cool 100 pages, I knew I was safe. It’s why I’m a big fan of fast-moving period pieces. You get historical depth but at a lightning fast discount. Let’s see if “What Remains” keeps me a fan of the format.

Achilles is dead.

Bastard Trojans shot him in the heel.

He died in one of the many battles the Greeks waged against the city of Troy, a city they can’t seem to infiltrate no matter how hard they try. Now, with their ranks diminishing, their food running out, and their spirits at an all time low, they’re about to give up.

That is until Odysseus, the heir apparent to Achilles, tells his commander, Menelaus, of a vision he had. They will build a giant horse. They will hide inside of that horse. They will then offer it as a gift to the Trojans. Then, once inside the town, they’ll open up the front gate to let the Greek Army in.

Unfortunately, there’s what you want and what you get. And nobody’s going to be building a giant wooden horse in one day. So Menelaus says to Odysseus, “We’ll build your horse. But it’s going to be tiny. And it’s only going to have room to hold two people.”

If that’s not bad enough, Odysseus is stuck with Achilles’ old page boy, Pyrrhus. And like an LA cop who doesn’t do partners, Odysseus doesn’t do page boys. Actually, that didn’t come out right. But you get what I mean. So Odysseus and Pyrrhus are stuffed in this tiny horse and whisked up to the front door of Troy.

Once inside, the Trojans begin their victory party, which allows Odysseus and Pyrrhus to slip out, blend in, and execute their mission. The only problem is that they won’t be able to open the front gate. Which means they must find the keys and open the South gate instead. And then, somehow, alert their army that a gate they won’t even be able to see is the one they must come through.

As Odysseus and Pyrrhus bicker away, each believing that a different approach is warranted, we start to wonder if they never should’ve gotten out of the Trojan horse in the first place.

What Remains of Troy isn’t a perfect script. But it’s pretty damn fun.

Steffan does a lot of things right here. All of the characters have depth. They have families, they have opinions about the war, they have conflicts with one another, they have contrasting ideologies. When someone speaks, you don’t feel like a writer’s writing it. You feel like that’s how it really went down.

The only time that didn’t happen was in the relationship between Odysseus and Pyrrhus, which, to be honest, was kind of strange. Here you have this great warrior, a king even, and this 12 year-old boy is giving him lip the whole time. Isn’t this back in the day where respecting your elders actually meant something? I know he was Achilles’ page, which gave him some street cred. But he’s still 12.

So it took me awhile to get used to that.

Once we did, however, some good things started happening. A good script always sets up a plan, and then the plan goes south. If the plan doesn’t go south, you don’t have a movie. So I liked how we’ve got this directive to open the front gate, but then once we get in, that option’s not available to us anymore.

So now the characters have to improvise. And this is where it gets fun. Because not only do Odysseus and Pyrrhus have to open the back gate instead of the front, but they have to somehow alert their army of the change, which is impossible since this is before the invention of cell phones. So Pyrrhus asks Odysseus how they’re going to accomplish this.

“We’ll figure that out later.”

This is known as a “lingering question” and is a very powerful storytelling device. Because the whole time we’re watching them try to get that gate open, we’re also thinking, “But how the hell are they going to alert their army?” It’s one more thing to keep the reader on edge. And that’s where you want your reader. ON EDGE. You don’t want them laying back in their couch, half-asleep, saying, “Yup, I knew that was going to happen” repeatedly. Because that’s 90% of all scripts they read.

So make sure the plan KEEPS GOING SOUTH.

I also liked the wild-card subplot of Helen being held prisoner in Troy. So now they don’t just have to burn down Troy, they have to find Helen and rescue her. So what do you do with that storyline? It’s a plan, right? So you should know the answer to this. That’s right. THE PLAN TO RESCUE HELEN NEEDS TO GO SOUTH. You see a theme here?

Then, overall, the script has a nice pace to it. It starts a little slow but it gradually picks up, and with each ten pages, it’s moving faster than the previous ten pages. It’s like this controlled acceleration until we’re this giant ball barreling down a hill.

My one major beef is that relationship. I think there’s a more honest way to explore it. Instead of Pyrrhus being this entitled Justin Bieber type cause he apprenticed for the greatest fighter ever, I’d like to see him more shaken, believing that there’s no more purpose for him in life. That’s how he starts off the journey. Then Odysseus comes along, the most unlikely of men to give a shit about this kid’s loss, and ironically becomes the one who helps Pyrrhus find his purpose again.

But it’s a minor league gripe in a script that mostly plays in the major leagues. Nice job by Steffan. I can see why this made the semifinals!

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: This is a great tip if only because I just experienced the opposite in a consultation script I just read. One of the things that readers hate the most is bulk character introductions. It’s so hard to remember a bunch of characters when they’re thrown at us all at the same time. With that said, sometimes you have to do it. And Steffan came up with a really clever way to deal with the problem. He creates an ACTION during his bulk character introductions to create a subtle separation between each character. The setup is a funeral scene that takes place next to the ocean, and part of the procession is the passing of a torch. So each time the torch is passed, Steffan introduces the character receiving the torch. It’s a small thing but it’s so much better than those mechanical bulk character intros that always leave the reader forgetting who half the people they just met were.

Genre: Mystery & Suspense/Fantasy/Horror

Premise:“A Christmas Carol” reimagined, told from the point of view of Bob Cratchit as he and Ebenezer Scrooge race to track down Jacob Marley’s killer — the same killer who now targets Scrooge as well as Cratchit’s son, Tiny Tim.

About: A semifinalist script (top 4) from our very own Scriptshadow Screenplay Tournament written by one of the most talented writers on Scriptshadow’s boards, who’s already once received a [xx] worth the read for her horror script, “The Devil’s Workshop,” about an abused makeup effects artist who experiences sinister forces after she accepts a job to craft a demon mask for a film.

Writer: Katherine Botts (based on the novella, “A Christmas Carol” by Charles Dickens)

Details: 114 pages

Today starts an interesting journey. I’m going to review all four of the Scriptshadow Tournament semifinalist scripts. The unique part of this is that I deliberately stayed out of the discussion so that I wouldn’t have any preconceived notions going into the reviews. I’m curious to see if the things I like are things that were added through the suggestions of the readers, and vice versa, if anything I didn’t like was suggested.

I’ve always thought this idea had potential. These types of mash-ups do well around town and the best of them end up on the Black List. My only question is, is this concept too complex? You’re mixing genres and stories that don’t traditionally come together, which is kind of the point. But that kind of chemistry always has an unexpected outcome.

Bob Cratchit ain’t your grandfather’s Bob Cratchit. The guy boxes on the side to supplement his lousy income from Ebenezer Scrooge. Cratchit only cares about one thing – keeping his family fed. And he’ll do anything he needs to to make that happen. Except use contraception.

So one day Cratchit is visited by the Ghost of Christmas Future, who uses his power to take him one day into the future, where Scrooge and Cratchit’s youngest son, Tiny Tim, have been murdered! When he gets back to the present he finds out Scrooge was shown the same vision, and that Scrooge’s old partner, Jacob Marley, was murdered as well.

So the group (Scrooge, Cratchit, and the ghost of Jacob Marley) head into the past to find out how Marley’s murder connects with theirs in hopes of keeping the future murder-free. These Back to the Future moments amount to seeing how each man grew up and became the person they are today.

For Scrooge, he used to be a fun-loving guy who Jacob Marley turned into a money-obsessed monster. And Cratchit, in trying to impress his boss, Scrooge, ended up beating a man to death, only to later marry that man’s widow. It’s all rather shocking. But how does it add up to these murders? And can the trio figure out who the murderer is before Christmas Day?

The first thing I noticed about Cratchit is that this is a very “high degree of difficulty” script. As we’ve talked about before, every script comes with a degree of difficulty. The higher the degree of difficulty (incorporating a couple of triple-axels into your routine), the higher the payoff. Unfortunately, there’s a flip side to that. The higher the chance of falling on your butt as well.

Cratchit is so ambitious that it feels like, somewhere along the way, Katherine lost track of the story. About 45 pages in, I was asking myself two questions I didn’t have great answers for: “Why are we with three people instead of one?” and “What exactly is their purpose in these Past scenes?”

The All-Star team-up approach was, in my opinion, a mistake. You already have a tricky narrative. You already have a unique setup. To distribute the story’s engine onto three characters instead of one distributes the focus as well, and that’s where I got lost. When we were watching Young Scrooge’s first girlfriend, I kept wondering, what does this have to do with a murder?

And that’s how the entire Past section played out for me. One giant backstory party that wasn’t connected to the murder storyline aggressively enough. So by page 60, I was numb to what was going on. I couldn’t figure out what their plan was to solve the murder mystery. And I was getting tired of all the character exposition.

Part of the problem is that the past had to satisfy three separate characters, where Dickens’ original story only had to satisfy one. And that simplicity made the original story much easier to tell and enjoyable to watch. The irony alone of learning how good of a person Young Scrooge was jarred us enough that we didn’t care about exposition.

If I were producing this, I would give the same advice I give to the majority of scripts that have lost their way – SIMPLIFY! A simpler story could solve so many problems here.

For example (and this is off the top of my head, so bear with me), let’s say Cratchit is shown the future, where Scrooge is murdered in his office, and Cratchit is being taken away by the police. Cratchit knows he’s been framed and so if he doesn’t find out who really killed Scrooge, he’s going to prison for the rest of his life. He’s got access to the three ghosts (past, present, and future) until tomorrow morning, and you’ve got a basic murder-mystery with a twist.

I’m wondering – and you guys or Katherine can answer this for me – if this script got overdeveloped. Cause that happens sometimes. Where you start off simple, and then the rereads become boring since you already know what’s going to happen, so you keep adding more and more plot, not because it’s making the story better, but because it’s making the rereads easier to stomach. Cause that’s kind of what it feels like to me.

Another inherent weakness with this format is how passive all the characters are whenever they go on these time jumps. We’re basically watching people watch people. And that’s as interesting as it sounds. It’s been awhile since I watched A Christmas Carol so I don’t know how they solved this. But I seem to remember they kept each sequence short, so the passiveness didn’t stick out as much.

But props to Katherine for going after this tricky concept. Even if I wasn’t as engaged as I wanted to be, I could feel the amount of sweat and tears that went into the characters, the backstory and the writing.

That’s one of the toughest things about screenwriting, is how hard it is to get all that stuff right, and then even when you do, you still have to nail the story. It’s like when I used to teach tennis. I could teach the student perfect form. But they still had to go out there and win the match.

I’ll finish by saying this. If you’ve come up with a complex concept like Cratchit, make sure you have a strong idea of how you’re going to execute it. These complex concepts aren’t the kinds of things you want to jump into and hope the answers will come to you later on. Have a plan, write up an outline, and get a good feel for the story before you write FADE IN.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Story Reminders. If readers forget why your characters are doing what they’re doing, that’s usually a bad thing you can’t recover from. But sometimes a story is just complex enough where simple reminders of why the characters are doing what they’re doing can be helpful. I needed a character to remind me a few times throughout that giant Past Section what we were doing here and why. Because the longer I went without knowing, the more my mind started drifting, and once a mind starts drifting, it’s only a matter of time before it drifts away, like a balloon on windy Sunday afternoon.