I’m taking the next couple of weeks off to finish reading all the Scriptshadow 250 scripts. I’m going to try and publish mini-posts here and there but can’t promise a post every day. I’ll most certainly comment on the Black List, which I’m assuming will come out later today (I’ll comment on it the day after – so likely Tuesday). In the meantime, feel free to comment on Star Wars The Force Awakens (opening this week!!!), the weekend at the box office (a disaster!), or anything else screenwriting/movie related that sparks your fancy.

As far as this weekend goes, the big story was the box office failure of In the Heart of the Sea. Except the only surprise here is that Warner Brothers didn’t see this one coming from a mile away and kill the project.

Ron Howard is probably the nicest guy in Hollywood, but he still thinks it’s the 90s. His movies have an old-fashioned feel in a marketplace that wants fresh and new. And Deadline was right. Why would anyone think that Chris Hemsworth’s fan base would want to see him in non-fantasy driven over-serious period piece?

So how did he end up in the picture? This is one of the major chinks in Hollywood’s system, and something they haven’t figured out in 30 years. When you’re shopping a movie to actors, you have “The List.” “The List” consists of your dream casting choice for the lead that’s simpatico with the studio’s need for an actor who drives box office.

So it’ll go something like “1) Christian Bale, 2) Ben Affleck, 3) Leonardo DiCaprio” and so on down the line. The thing is, if none of those actors bite, you now dip into people who are no longer right for the role but who the studio will still greenlight the movie for. Because you want to get the movie made, you go with them, convincing yourself you’ll “make it work.” And while sometimes they work out (Keanu Reeves in The Matrix) they usually don’t.

When they don’t, you get something like In the Heart of the Sea, a movie that needed an older more established actor who audiences identified with in this kind of genre. Bale actually would’ve been perfect. Still, even if you get all these things right, you’re still making a movie where the main goal is to kill a beloved animal. This isn’t a shark. It’s a whale! I just don’t know why anybody thought this would work.

Speaking of whales, the trailer for the new Independence Day film just dropped and I have to say, something very strange is going on here. The initial reaction is over-the-moon when I could swear this isn’t even better than the trailer for Battleship. I started looking into the commenters, to see if, coincidentally, this is the first time they’d ever commented on something. But many of these commenters have established history. Am I off my rocker here? Do people actually think this looks good? It doesn’t even have that “must-see” shot that made the original’s trailer so famous. Help me understand, Scriptshadowers!!!

TWITTER FUN!

Moving on to a funner topic, The Force Awakens premieres TODAY exactly 6 blocks from my place! I’m going to try and make it up there and tweet a few pictures. And speaking of tweeting, since I’ll be reading contest scripts non-stop the next 2 weeks, I’ll be live-tweeting script-thoughts throughout. Just follow me at (@Scriptshadow) on Twitter to hear my sometimes insightful but mostly disposable thoughts. You can also search for the hashtag – #ss250 – to see all tweets related to the Scriptshadow 250 reads. Enjoy!

Get Your Script Reviewed On Scriptshadow!: To submit your script for an Amateur Review, send in a PDF of your script, along with the title, genre, logline, and finally, something interesting about yourself and/or your script that you’d like us to post along with the script if reviewed. Use my submission address please: Carsonreeves3@gmail.com. Remember that your script will be posted. If you’re nervous about the effects of a bad review, feel free to use an alias name and/or title. It’s a good idea to resubmit every couple of weeks so your submission stays near the top.

Genre: Comedy

Premise (from writer): Three socially impaired women, who think they have superpowers during PMS, believe they must find the remedy to menopause or risk losing their powers forever.

Why You Should Read (from writer): This is my attempt at a superhero script where there are no actual superpowers. It’s just three women who make some questionable choices because of issues with self-perception. It’s meant to be farcical fun so the humor tends towards sophomoric and crude. Curious what you think.

Writer: Stephanie Jones

Details: 91 pages

So a debate popped up in last week’s Amateur Offerings. Longtime contributor Stephanie Jones was getting a lot of votes, and some were saying that the reason was because everyone knew her, and that Amateur Offerings isn’t a “vote for your friends” contest, it’s a “vote for the best script” contest.

So here’s my take on that. I have not read all of the scripts so I can’t tell you which one is the best. But what I will say is that this is exactly how the real industry works. There are communities of people throughout Hollywood who work together. And when one of those people brings a project to the group, that project takes precedence over Rando Number 1’s project. It’s just how it is.

So how was anybody supposed to beat Steph this weekend? The same way you beat anyone in the real industry – YOU WRITE SOMETHING SO DAMN GOOD THAT THE GATEKEEPERS CAN’T OVERLOOK IT. And it doesn’t look like anybody did that last week. So tough cookies!

Weep, Crave, Loathe introduces us to the 35 year-old trio of lifelong friends, Ruby, Zora, and Peggy. Ruby is the plumper of the group, Zora is the crybaby, and Peggy is the angry one. There’s one important thing you need to know about these girls. They think they’re superheroes and that these traits (eating, crying, fighting) are super powers. They also believe that their periods bring out these powers.

All of this dates back to seemingly insignificant talks their mothers had with them when they were toddlers. But as you know, kids can take things literally, so when mom said that crying was a superpower, or that eating was a superpower, the kids just… believed them. All the way until they were adults!

But here’s the problem. At 35, the women are approaching menopause. And menopause means no more periods! And no more periods means no more powers! So they read about a procedure that allows doctors to slice off a piece of the ovary and save it for later, allowing the women to continue to have periods after menopause! All three women are in!

In the meantime, the group decides they need to spread their message to the world and therefore record a video of their powers in action. This video goes viral, and all of a sudden the entire world wants to know more. After going on a period-powers tour, the fame brings about issues in the girls’ friendship and the three break up!

We watch as they each learn to live life on their own, and to finally come to terms with the reality that their powers aren’t powers at all, just part of life. Or DO THEY???

Comedy is weird. It’s the only genre where you can break a bunch of the rules and still write something entertaining. As long as people are laughing, you’re doing a good job. Throw in subjectivity and grading comedy becomes a bit like grading a beauty pageant looking through a kaleidoscope.

I’m saying this so everyone knows this is just my opinion on Weep, Crave, Loathe, and if you want to know if this script is funny, you should read it and decide for yourself.

For me – I’m not going to lie – I struggled through it. And it came down to three problems. First, the humor was VERY broad. As in a character gets completely run over by a car and it’s played for laughs broad.

Second, the humor was very in your face. We only ever see Peggy, the angry girl, sharpening knives, watching shark videos, or trying to start a fight. Ruby, the fat girl, is only ever talking with her mouth full, or going to the supermarket to steal multiple boxes of pizza bites. To say that the humor was on-the-nose may be the understatement of the century.

But the biggest problem was that I never understood the concept. A 35 year-old woman believes that crying is a superpower because of a 3-second conversation she had with her mom when she was 5? Isn’t crying something you’d talk about thousands of times with numerous people over the course of 30 years, in which case you’d learn, at some point, that crying wasn’t a superpower?

Unfortunately, if the reader doesn’t buy into the concept, everything after that is a moot point. You’re building a story on a foundation that isn’t solid.

But even if I had bought into the concept, I still didn’t understand the goal. They’re going to have this surgery to take out a part of their ovaries so that they can continue to have their periods (and thus their superpowers) later in life? So when are they reattaching these ovaries? As soon as they get menopause? Is it then permanent? You can have your period and get pregnant indefinitely? Or does it only work for a limited time? And if so, how long? And if it’s only for, say, a year, then is making this the focal point of the plot even worth it? None of that was clear, which was a double-whammy as far as understanding what was going on in the screenplay.

In addition to this, the plot is stretched thin, giving everything a hurried “first-draft” feel. It’s something I talked about yesterday. Everything in first drafts takes too long. The big goal here is to have a surgery that will cut off part of their ovaries so they can continue to have superpowers after menopause.

The script takes up 16 ENTIRE PAGES of sporadic doctor visits just to determine if the women qualify for the procedure! Are we really going to spend 20% of the script just to get people approved for a procedure – in a superhero movie, no less, where audiences are expecting characters to go out and do superhero things? I think Steph could’ve gotten through this section in a page and a half with all three characters via a montage. It’s not the kind of plot point that warrants a huge chunk of screenplay real estate.

I will say this for Steph’s screenplay though. You won’t be able to predict where it’s going. Having the friends split up and figure life out by themselves for the last third of the script was an unexpected choice. But it also, once again, calls into question the concept. If you’re promising people a super-hero movie, even if it’s a different take on one, are they going to be satisfied moving into a character-piece that has little to do with the initial concept for the final 40 pages?

Put plainly, Weep, Crave, Loathe is a script that’s flawed at the concept level. Most of the script’s problems can be traced back to that shaky foundation. I’m trying to think of a way into this story that would work better. Maybe these three women really are superheroes? With REAL super-powers. But the only time they get these powers is during their periods, so they’re super bloated and moody whenever they’re out saving the world? I don’t know though. Is that sexist? The world is so sensitive these days I have no idea if that would fly.

So yeah, you can basically erase all of my issues if you go back and fix the concept. But that’s ultimately up to Steph and whether she thinks it’s flawed in the first place! What did you guys think???

Script link: Weep, Crave, Loathe

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: The reason you hear myself and other screenwriting junkies tell you to write something great isn’t because the professional competition is great. It’s because everyone likes working with their own people on their own stuff. The only way to break through that is to write something so good that they’ll choose you over their friends. So write the best script you’re capable or writing and then you’ll have a legitimate shot.

What I learned 2: If a plot thread is going to take up a lot of time in a script, it better be important. Otherwise, we’re going to wonder why the writer is taking so long to tell a seemingly inconsequential piece of the story. I didn’t think getting approved by a doctor for a procedure should take 16 pages. We could’ve built in a much more important plot line that felt worthy of a 16 page investment.

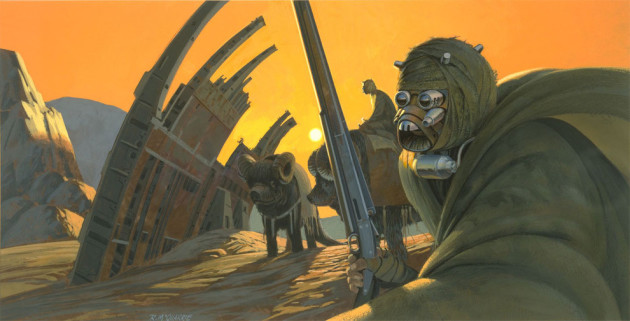

We’re so close I can taste it! My favorite day of the year. A day when people come together to share love and food and joy. A day when a man dressed up in a costume can make even the most hardened Grinch melt into a warm puddle. A day when it seems like the universe is binding everyone together. I’m talking, of course, about December 18th, Star Wars: The Force Awakens opening day.

Which is what inspired today’s post. As I was going through all my Star Wars scripts, I found this, the very first Star Wars treatment from the bearded magician himself, George Lucas. And what did I notice upon reading this document? Genius? The future of a 20 billion dollar franchise? A slew of pop culture phrases that would permeate the very fabric of our society for 30 years?

Nuh-uh.

I found something that was going to require a ton of fleshing out before it approached anything remotely close to a ground-breaking movie. You can read it for yourself but here are the highlights…

1) The attack on the Death Star comes without explanation in the very first scene.

2) It takes place not a long time ago and not in a galaxy far far away, but in the 33rd century and in our very own galaxy!

3) Luke Skywalker is a full-formed general who’s guarding Leia at the beginning of the film.

4) There is no mention of “The Force.”

5) There is no Obi-Wan Kenobi.

6) There is no Han Solo or Chewbacca.

7) R2-D2 and C-3PO are replaced by two bumbling human bureaucrats.

8) Luke and Leia are transporting “spice” through an Imperial section of the galaxy.

9) Luke, Leia and the bureaucrats get marooned on a desert planet, where they must take a road trip across the planet to get to a spaceport and fly to the safety of a friendly planet. This desert planet is where the majority of the movie is set.

10) We never actually go to The Death Star.

11) There’s no Darth Vader.

12) They end up at the planet Yavin, where Luke and Leia get split up, and Luke must train a bunch of youngsters to help him rescue Leia.

This is what you get in your first treatment, your first outline, or your first draft. Ideas. But you don’t yet get something original that brings those ideas together. It’s a blob of first-take concepts in search of a structure. Each draft then allows you to get rid of pieces, add pieces, and move the remaining pieces around, until you find that great movie every good idea has the potential to be. In fact, here are five of the most prominent beneficiaries of multiple drafts.

ELIMINATING INFLUENCES

We are all slaves to our favorite films. They are the reason we got into this business. And whether we know it or not, every script we write is a version of one of these movies. That manifests itself in characters, plot points, and ideas from these films seeping into our first drafts. You see it here. A desert planet. Transporting “spice.” Our characters battling giant beasts in the middle of the desert. “Dune,” anybody? What subsequent drafts allow us to do is identify these influences and weed them out. Or at least push them into the background, away from the main plot. If you don’t go through this crucial step, you’re going to get a lot of people criticizing you for copying [insert your favorite movie here].

PLOT OVER CHARACTER

When you write an outline or a first draft, you barely know your characters. As such, you tend to focus on the plot. And we can see that here. This treatment is all plot and doesn’t mention once anything about the relationships between the characters. We don’t even know how Luke or Leia feel about one another. Subsequent drafts allow you to live with your characters for awhile just like living with real people. You get to know them, and once you know them, you can start building a life around them, as well as building the relationships between these people. There’s nothing that benefits more from rewriting than character.

IDENTIFYING WHAT’S COOL AND WHAT ISN’T

When you write a first draft, you’re not sure what’s cool yet. You have ideas, but mainly you’re just throwing a bunch of shit at the wall. In subsequent drafts, your goal is to identify which pieces of shit are sticking. You then start crafting your screenplay around these hotspots. A perfect example here is the Death Star. It’s mentioned at the beginning of the treatment then never again. Over the course of rewriting the story, Lucas obviously realized what am amazing and interesting idea this space station planet was. He’d make it the centerpiece of the villains’ story and build an entire sequence inside of it. Never get hung up on the ideas in your first draft. Be open to exploring new avenues, particularly anything that looks like it might have potential to make your script more interesting.

NO VILLAIN

I don’t know why this is, but it’s pretty common that first drafts don’t have villains. I think it has something to do with the writer concentrating so hard on their heroes and the journey (the plot) that they don’t think about creating a villain. I read tons of scripts that have gone into the 5th or 6th drafts that still haven’t included a villain. That’s not to say that every movie needs a villain, but usually when there’s an edge missing in your story, it’s because you don’t have a villain. And we see that here. This treatment is straight-forward sci-fi fodder with people driving across deserts and fighting aliens. Darth Vader had not been created yet. I want you to think about that for a second. The greatest villain in the history of cinema was not in George Lucas’s first treatment. Might you be depriving the world of the greatest villain in history?

COMBINING TIME

The biggest issue in first drafts is that everything takes 10 times longer than it should. And it makes sense why. Your brain is still working everything out and it extends the sequences in the film as a result. Subsequent drafts require you to compress time as much as possible. For instance, it takes Luke and Leia 45-60 minutes to travel across the desert planet and get to the spaceport of “Mos Eisley.” In the movie, it takes 1 second. We’re in Obi-Wan’s hut, and then a second later we cut to Obi-Wan and Luke, having driven to a cliff, looking over Mos Eisley. Here’s a phrase to remember: “Time combine.” Start combining that time, folks!

Hope this helped with your current script. May the force be with you, always!

Genre: Sci-fi

Premise: A calloused medical actuary is sent to evaluate an exciting new procedure that could cure human disease forever.

About: This script has not yet sold but finished number 7 on this year’s Hit List, one below The Water Man, and one above Pale Blue Dot. The writer, Takashi Doscher, is actually a documentary filmmaker who specializes in sports documentaries. His film, A Fighting Chance, about a wrestler without any arms or legs, sold to ESPN’s prestigious 30 for 30 series. He’s repped by spec sale king Mike Esola, who recently moved from WME over to UTA.

Writer: Takashi Doscher

Details: 103 pages

I’m still trying to recover after yesterday. “Libertine Fever” is a real thing, according to the national survey of screenplay diseases. It occurs after a particularly bad script, sending the reader into a spiraling depression that starts with ordering two Dominos pizzas at 12:49 a.m., and ends with waking up in a pile of Nutter Butter crumbs (and strangely, no packaging in sight). I will neither confirm nor deny that any of this happened to me. But I will say that I’ve added a new day of therapy to my week, putting the total at 4 (my therapist is off Thursdays).

You’d think I wouldn’t be able to make it though another Hit List script after the Libertine debacle, but this next script has been getting some solid marks from Scriptshadow readers, and high-concept sci-fi sounded like the perfect answer to whatever the hell genre I endured yesterday.

Dylan Simms is an actuary. If you don’t know what that is, don’t worry, cause I don’t either. From what I could tell, Dylan works for a giant medical company that invests in a lot of projects. When we first meet him, he’s telling two scientists (who are also a couple) that their infertility project has been nixed. The two are devastated, and plead for more time, but the calloused Dylan tells them not to let the door hit them on the way out.

Telling people he doesn’t care about unborn babies seems to be Dylan’s thing. When his girlfriend, Nicole, informs him later that she’s pregnant, he tells her that she needs to get an abortion STAT. Nicole breaks up with him on the spot, to which Dylan barely reacts.

Later, Dylan’s boss sends him to a top-secret project the company is working on to determine if it’ll fly legally. Imagine Dylan’s surprise when he finds out the project is shrinking people down and placing them inside of bodies so that they can fix fractures, cure diseases, and live forever! Dylan is even shrunk down and thrown inside of someone’s body to get an up-close look at the technology.

However, when the vessel they’re in is attacked by a group of T-cells, Dylan is thrust out of the ship in just a protective suit. Everyone else dies. Dylan eventually makes audio contact with mission leader Rebecca Curry, who’s back in the lab, and she navigates him through the insane geography of the human body in an attempt to save him.

Along the way, we learn that the woman whose body we’re in has Lupas, which is causing all cells everywhere to attack everything, especially foreign bodies like Dylan. As Dylan eventually navigates himself to the center of the body, he sees that the woman is pregnant. Looking at this giant unborn child flips a switch in Dylan, and now he’ll do anything to get out and save the child he told Nicole to get rid of.

A lot of writers ask me, “What’s the point of writing a spec that would cost a studio 150 million dollars when there’s a 99% chance they’re going to spend that money on already established IP?” The point is that writing one of these specs proves to the studios that you can do it. Which means you might get hired to write one of those 150 million dollar IP properties. So sure, you may not get your script purchased. But does it matter when you cash that first half-a-million dollar assignment check six months later?

Now you may be one of those writers who’s actually gone the 150 million dollar idea route and gotten nowhere. You then deluge all the internet screenwriting message boards with your tale: “I tried the huge spec route,” you say, “and I didn’t get a single bite. Studios aren’t interested in these scripts!!!”

Let’s be clear about something. Every strategy you engage in is predicated on you actually writing a good script. If you write a big popcorn flick and it sucks, that doesn’t mean your strategy was a bad one. It means you have to work on your writing. Of course, it’s very hard to judge your writing, since every writer is hopeful and taste is subjective.

I can’t help you with that without reading your screenplay. But what I can help you with in regards to popcorn flicks, is understanding what Hollywood responds to. New writers believe that writing these script is all about the action. It’s all about the set pieces and the creativity of the world. And that’s part of it. But that pales in comparison to what Hollywood is really looking for – which is to see if you can find an emotional center to a giant story.

Take the movie San Andreas. It’s a big goofy summer action film. The definition of a popcorn flick. What is it about? An earthquake, right. No, it’s not about an earthquake. It’s about a father trying to save his daughter and bring his family back together. I can hear you cynics saying, “but that was so cheeeeesy.” Okay, call it whatever you want. But Hollywood wants you to move the audience emotionally. Which means your action script needs an emotional core.

That’s what Doscher does here. He creates this character who doesn’t want children, who always puts work and himself above others, and uses this journey to help him see the other side of coin. This isn’t so much about a man travelling through a body as it is about a man coming to terms with who he’s become and whether he wants to keep being that person for the rest of his life.

Did it work? Ehhhh, that’s debatable. An argument can be made that it was too on-the-nose. And yeah, I felt Doscher went over the top at times (Dylan’s battle against the T-Cells that attack the baby’s placenta was a bit much – how come the T-cells waited 24 months, until the exact moment when Dylan entered the uterus, to attack the baby?). But the point is, he committed to exploring the emotional side of the movie and that’s what Hollywood wants!

ANYBODY can write a big action set piece. They’re all the same. Car chase this, building falls down that, gun gun gun, bang bang bang, robots. But it takes a real writer to move people (or at least attempt to), and that’s how you stand out in this genre.

Despite this endorsement on the script’s approach, The Life Inside ultimately fell short for me. Like I said, it was too on-the-nose. And it didn’t surprise me enough. I felt there was more of an opportunity with the mystery of whose body we were in (it ended up being someone random). Also, there’s this whole second older submarine Dylan swims to that’s military in nature. It seemed like we were going to get some cool twist. But it never happened. It was just another shrunk submarine.

Which sucks. Because I thought the angle here was spot on. With a little more practice at subtlety, I think Doscher could be a writer to watch out for.

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: I’m thinking we need to update this exchange in movies: “Mr. Smith.” “Please, call me Harry.” “Harry, I was wondering…” It may be the most overused exchange in all of writing. Impomptu Scriptshadow writing challenge: Give us a NEW variation (or entirely new exchange) of the “Call me [Name]” exchange.

Genre: Drama? Comedy?

Premise: Inspired by the Dominique Strauss-Kahn scandal, The Libertine follows the aftermath of a French politician accused of sexually mistreating a hotel maid.

About: A hot spec script that sold to Warner Brothers a few months ago from Ben Kopit, an up-and-coming screenwriter who only recently graduated from UCLA’s MFA screenwriting program.

Writer: Ben Kopit

Details: 99 pages

This script has gotten a lot of heat around town the last few months. The only reason I’ve avoided it is because it’s not my thing. I don’t even know who Dominque Strauss-Khan is, nor do I care about world leaders in other countries and their extracurricular activities.

But the script won’t go away. It finished high on the just-released Hit List, and with its political leanings, you can bet your ass the politics-obsessed Black List is going to give it high marks. Which brings us to today. I guess I’m reviewing The Libertine!

Maurice Lunel-Caspi, 60, is a major player in the French government. Which makes the fact that he inappropriately touched a maid at a New York hotel a big deal. The maid went to the police, and now Maurice is being kept in New York on house arrest until trial, where his media titan wife, Edith, is reluctantly staying with him.

“Reluctantly” may actually be an understatement. Edith HATES her husband. Not because she knows he’s guilty, but because she knows he’s been fucking anything with a protruding chest for as long as they’ve been together, and therefore, it’s likely that whatever he’s been accused of is true.

The Libertine is possibly the most unambitious screenplay I’ve read this year. All we do for 99 minutes is hang out in this dreadfully boring apartment while Maurice, Edith, and their angry daughter, Jaqueline, argue. I guess later on, Maurice’s lawyer makes an appearance to update him on what’s happening with the charges. And maybe that could be considered “story.” But it’s dealt with so passively that it could just as easily be seen as an interruption.

In the end, the fighting only increases, and everyone’s hate for one another grows from a 7 to an all out 10, until finally, in the end, through no doing of our characters’ actions (because god forbid our characters actually have an effect on the story) Maurice learns that the charges against him have been dropped because the maid has some shady immigration issues.

Were you one of the people who, after seeing Jobs, said to yourself, “Man, I wish there was a movie out there with a main character 180,000 times more of an asshole than this guy,” then my friends, I’ve found you your movie!

I have never – I don’t think in all of my script reading – read a script with a more deplorable main character. I don’t know if Maurice touched this maid or not (and neither does the script – it’s not interested in exploring anything that involves mystery, drama, interest, or suspense). But what I do know is that this married gentleman whose wife has given him unimaginable wealth, invites over prostitutes the second she leaves the building, jacks off when he’s bored, goes to online sex chat rooms to order women around, takes his wife’s favorite pen and, when she’s not around, rubs it inside his crotch and asshole before replacing it, and after somehow finally getting his wife to care enough about him to have sex with him again, starts surfing porn sites not five minutes later.

But here’s the thing about The Libertine. It’s not just Maurice. EVERYBODY in this script has more anger, sadness, evilness, negativity, narcissism, whininess, and overall shitiness than anyone you will ever meet in your life. Edith, the wife, is a bitch as well. And the one person who had a chance at being a likable character, the social crusading daughter who hates what her dad has done, is just as big of an asshole as her parents.

Everybody just yells at each other here. And there’s NO STORY. NONE! What is the goal? What is anybody attempting to do?? Even the problem, the thing that needs to be dealt with, is being tackled by a lawyer character in a storyline that never reaches the screen. So we’re not even seeing the interesting stuff. We’re just watching these miserable despicable human beings argue while the real story happens behind them.

The killer for me was the mid-point. We get this dinner scene with another man being kept under house arrest in the same building – a financial swindler. Why does this dinner occur? Oh, because Maurice feels like having a dinner with another person under house arrest. There’s no actual STORY REASON for this dinner to occur, of course. It’s there because this script is so threadbare, so devoid of a point, that if it wasn’t there, it would be 70 pages at most. So sure, why not invite a random character with no ties to anything and no reason to actually be in the story into the mix. Makes sense to me!

And if you had to make a bet, would you put money on this gentleman and his wife being nice caring people? You know, maybe to create some contrast in the conversation for once? Of course not! They’re total swindling assholes JUST LIKE OUR MAIN CHARACTERS. I guess when you’re holding an Asshole Fest, the policy is only assholes allowed.

The Libertine attempts to conclude its “story” with some sort of ironic anecdote. Maurice, in order to get back in his daughter’s good graces, pulls a favor to get her a job with an old friend. But when she meets this friend, he ends up making a pass at her. I guess we’re supposed to feel some karmic retribution that this man finally understands what it’s like to be on the receiving end of sexual abuse. But we hate everybody in this script so much, including Jacquline, that this moment leaves us feeling nothing other than contempt for coming this far only to be subjected to a half-assed cobbled-together ending. It’s one last-ditch attempt for the script to seem relevant.

I’m begging those of you who liked this enough to vote for it. Tell me what I’m missing. What is it that makes this script appealing? I honestly can’t find a thing. I suppose the dialogue moves quickly, but it’s laced with so much anger that the snappy rhythm is undermined by pure hatred. Help me understand!

In the meantime, please don’t let anything with a heartbeat near this script less they turn to stone. Now excuse me while I go google puppy images for the rest of the night.

[x] what the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: One of the things that works well in screenwriting is contrast. You want extremes clashing against each other. So if someone’s a real asshole, you want to put them in a room with someone who’s really nice. That clash in ideology typically results in a lot of interesting dialogue. But if all the characters are assholes, there is no contrast. It’s just empty conflict, a lot of yelling and disagreeing with the same boring predictable tone. That sums up every single page of The Libertine.