Hey guys. Today is going to be a short post as I’m super busy. But basically I wanted to talk about scenes. So much of what we discuss revolves around concept, structure, and character. But the reality is, we have to write 60 scenes in a screenplay. And if you don’t know what to do inside of a scene, it doesn’t matter how good your concept is, or your structure is, or how your characters are.

Now I will put a disclaimer on here that there’s no such thing as a rule that applies to everything. Obviously, there will be exceptions. But this rule should be utilized a ton. You see, as I’ve opened up a couple of early entries for the Scriptshadow 250, I’m seeing a scary trend. The scenes are boring. They sit there. There’s not a lot going on. It’s the dreaded case of “nothing happens.”

Luckily, today, I’m going to teach you a trick where you can make sure this doesn’t happen to you. All it entails is that in each scene, you add a problem. That problem will lead to conflict, which will result in drama. And as you all know, drama is entertainment.

To see this in action, go back and study your favorite films. I guarantee you that in 95% of the scenes, there will be a problem.

The best script to see this in action with is the greatest spec ever written, American Beauty. Nearly every scene in that script introduces a problem. Lester is on a sales call at work but the person doesn’t want to buy anything. PROBLEM. Lester is called in to see his boss, who tells Lester that he’s firing him. PROBLEM. The family tries to have dinner together until the daughter complains about the music they have to listen to all the time, which leads to an argument. PROBLEM. Even tiny scenes, like Lester going to the car in the morning introduce a problem (Lester dropping his briefcase, spilling the contents everywhere, making everyone late).

In a more recent film, American Sniper, the opening scene has Chris Kyle trying to decide whether to shoot a child. PROBLEM. When he gets home, his wife is in bed with another man. PROBLEM.

If you go back further in film lore to Star Wars, the opening scene has the Empire capturing and boarding the Rebel ship. PROBLEM. When R2-D2 and C3PO land on Tantooine, they have no idea where to go. PROBLEM.

One thing to remember is that the problem doesn’t always have to happen to the hero. The problem can happen to anyone in the scene. So, again, in Star Wars, when we finally meet our hero, Luke, he’s buying droids from the Jawas. But the problem occurs from the side of C3PO. He’s been purchased but it looks like he’s going to be separated from his friend, R2-D2. PROBLEM.

Once a problem is introduced into a scene, so is uncertainty. And uncertainty creates curiosity in the reader/audience. People have a natural inclination to keep reading to see how the problem gets resolved.

Let’s say I have a scene between Joseph and Cara, who are on a first date. Let’s say it happens at a diner. In it, the two talk about their likes and dislikes – a typical “get to know each other” scene. There’s nothing particularly wrong with this scene, especially if there’s some interesting revelations about the characters’ pasts, or if the dialogue is witty and clever.

But you can do all of that AND engage the reader by adding a problem. Maybe, for example, Cara’s crazy ex-boyfriend shows up unexpectedly. He asks her where she’s been and why she hasn’t been answering his phone calls. He then turns to Joseph and demands to know who he is. PROBLEM.

Now there are situations where you want to hold back on the problems. For example, let’s say you’re going to kill a character off in scene 4 of your script. You might want to use the first three scenes to build up an idyllic life between that character and our hero. In this case, there’s a deliberate strategy to creating a problem-free sequence – so that the death impacts the audience that much more when it happens.

But I’d recommend adding problems into even those scenes. They won’t be as big as, say, the Empire boarding a Rebel ship. But even the smallest problem leads to conflict and conflict is always going to liven a scene up.

So the first thing I want you to do with your Scriptshadow 250 script is to go through each and every scene. Is there a problem in each of those scenes? I’ll repeat what I said before. There doesn’t HAVE to be a problem in every scene. But if a lot of your scenes are lacking a problem, I can almost guarantee that your script is boring.

Problem-free scenes tend to happen most when the writer is setting up his characters or writing a lot of exposition. They believe they have a right, since screenwriting is hard, to dribble out boring scenes during these moments. I’m here to tell you that that is a BAD IDEA. You don’t get to take scenes off, no matter how hard they are to write. Go into those character intro and exposition scenes and find a problem to add. I guarantee you the scenes will be better.

Also remember that each problem should vary in intensity. Don’t try to write some earth-shattering problem into each and every scene or you’ll exhaust the reader. A problem could be as simple as your character goes to get coffee and someone cuts in front of him. PROBLEM.

Or maybe the barista gives your character the wrong coffee and he has to go back in line. He, then, could be the person who has to cut others. But everyone tells him to get back in line. PROBLEM. Add a time constraint (he has to be in a big meeting in 5 minutes) and now you have yourself a scene. It really is that simple.

The reason this trick works is because characters become the most interesting when they’re forced to act. That’s when we learn the most about them. By introducing a problem, you force your character to act. And however they choose to react tells us loads about them, in addition to creating conflict in the scene, in addition to making the audience curious about what’s going to happen next . To that end, this might be considered a super-tool. Go ahead and use it in your scenes and report back in the comments on how it went. Good luck. And keep working on those Scriptshadow 250 scripts!

Genre: Comedy

Premise: After America’s favorite astronaut nearly loses his life in an accident, the government decides to rebuild him into a bionic man. The problem? Money for the project is tight.

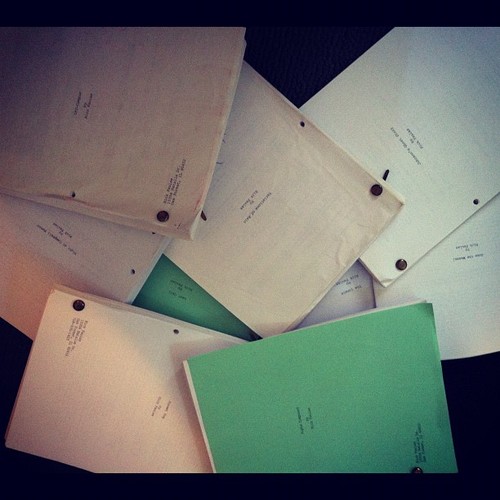

About: Jonathan M. Goldstein and John Francis Daley are one of the hottest comedy writing teams in Hollywood. They wrote Horrible Bosses, Cloudy with a Chance of Meatballs 2, and recently won the plum assignment of rewriting National Lampoon’s Vacation. This is the script that got them noticed. It landed on the 2007 Black List, and although it never got made, it started their careers.

Writers: Jonathan Goldstein and John Dale

Details: 100 pages (undated)

Aspiring screenwriters all live with the same dream of writing a screenplay, getting it into the right hands, said hands loving it, and a studio sending them a check for six figures. While those moments always get the most press because of how rare they are, the more well-known path is for a writer to write something that shows promise, then use that to build credit in the industry, which they’ll then cash in on later with another spec.

Cause what happens when you’re a “nobody” writer and you write something good is that everyone in town is afraid to buy it. They don’t want to be the “dummy” who just spent a boatload of money on an unknown. Tinseltown people are horrified of being the laughing stock. But what that first script does give the writer is “street cred” so that, now, when they write another script, people aren’t as afraid to pull the trigger because the writer is no longer “unknown.”

That’s the kind of script we’re dealing with today. It proves to the industry that you’re close. How do you write one of these scripts? One of two ways. Come up with a great idea and execute it adequately. Or come up with a so-so idea and execute it exceptionally. The former is the waaaaaay easier route to go, and that’s squarely where $40,000 Man lies. This is a really clever concept. It takes a known property (the 6 million dollar man) and flips it on its head with a funny question (What if they had to make the bionic man on a budget?). Let’s see how the script fares.

It’s 1973. Buzz Taggart is America’s favorite astronaut – a star amongst the stars. His only crime is that he’s a few craters short of a full moon. And one day when some annoying teenagers challenge him to a drag race, his idiocy gets the best of him. He crashes badly and the government tells him that the only way they can save him is if they put him back together with bionic parts.

Buzz is happy to be alive, don’t get him wrong, but he’s less than thrilled when he finds out this “program” he agreed to is on a super tight budget – as in only 40,000 dollars. This has left his new supposedly awesome bionic powers somewhat… lacking. For example, his bionic arm just randomly punches people. His bionic legs (which only run 1 mile an hour faster than the average human) can’t stop once they start going. Oh, and his bionic nose can only smell one thing – shit.

Buzz is placed on his first mission right away, but as you’d expect, it goes horribly. So the government SCRAPS the project due to money, leaving poor Buzz living life as a rapidly deteriorating heap of scrap-metal. To make matters worse, he finds out that the government was lying to him! Buzz was a guinea pig. A pre-cursor to a newer better bionic man worth SIX MILLION DOLLARS!

One year later, depressed and washed up, Buzz gets a call. The six-million dollar man is missing! And they need Buzz to save him. Buzz demands that they upgrade him first, so they tack on 10,000 dollars worth of new parts which… don’t really do anything. Buzz then heads to an island run by terrorists to save his replacement and become a hero once more. In order to do so he’ll have to overcome a body that may be the worst government project in the history of the United States.

The $40,000 Man is pretty much the perfect career-starting script. That’s because while it may not be great, it shows a lot of potential. The first way it does this is by nailing a good concept. This is a seriously over-ignored aspect of screenwriting. No matter how many times I talk about the importance of it on the site, 80-90% of the scripts submitted to me are dead in the water before I read a word.

Either the idea’s devoid of conflict, isn’t exciting enough, lacks irony, or isn’t big enough. A lot of writers delude themselves into thinking that they can turn mundane topics into gold with their execution. And sometimes you can (staying within the comedy genre, “The Heat” comes to mind). But go look at the top 50 grossing movies every year over the last 10 years and you’ll rarely find small ideas. Almost all of them feel “larger-than-life.” And that’s a good way to look at concept. Think big.

In addition to a big idea, irony is a great way to set your concept apart from others. Since $40,000 Man is based on an ironic premise, it immediately shows the industry that the writers know what they’re doing.

Once you come up with a good concept, you must execute it adequately. And that mainly means structuring your story well. It doesn’t have to be perfect. Again, you’re just trying to show that you have potential. But you must show that you can sustain a story for 110 pages. One of the easiest ways to spot a new writer is a script that loses momentum around the page 40 mark. This is where most beginners fall because they don’t yet know how to structure their screenplay so that the story lasts.

For example, in $40,000 Man, Buzz gets fired and abandoned at the mid-point of the story. This was an unexpected twist that gave the story new life. Soon after, he’s re-recruited, ironically, to save the 6 Million Dollar Man, and the story builds from there until the climax. The writer who’s not yet ready writes a few “fun” scenes once Buzz gets his bionic powers and then isn’t sure where to go next. To him, the “fun” scenes were his whole idea so he hasn’t really considered what to do once they’re over (hint: it starts with adding a goal!)

Just a warning. Readers only give you leniency with your execution IF YOU HAVE A GOOD CONCEPT. If you already botched the concept, so-so execution will be the nail in the coffin. For writers who argue that their script was attacked for lazy structure/execution while [recent spec sale] had lazy structure too and still sold – chances are it’s because their concept was a lot flashier than yours and therefore received a longer leash from the reader.

Remember, any idiot in Hollywood can spot a great script because there are only 2-3 of them a year. With everything else, agents and producers have to spot potential. Potential in a script that’s not yet there or in a writer who’s not yet there. If you can give them a great concept and an adequate execution, you’ll have a shot at getting noticed. These scripts are “table-setters.” They’re not amazing, but they set the table for you to start selling screenplays.

By the way, this one shouldn’t be hard to find. It’s a 2007 script that has been traded forever. So ask around and you’ll likely receive.

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Set up late-arriving characters earlier if you can. A common beginner mistake is to throw new characters into the story late. Because the characters have little time to make an impression, the reader never truly connects with them, so they, along with whatever storylines come with them, fall flat. This happened with the Six-Million Dollar Man (Steve), who comes into the story around page 70. I barely knew this guy so I didn’t care if Buzz saved him or not. You should try to set up every important character as early as the story will allow you to. So here, why not make Steve someone Buzz worked with at NASA? Maybe Steve worked in a lowly position and Buzz was a dick to him. I don’t know. But just by creating a history between these two, the Six Million Dollar Man becomes way more relevant as he takes center stage in the 3rd act.

Genre: TV Pilot – Drama/Thriller

Premise: When the LA police force tries to cover up a killing by one of their officers, they’re underhanded by a clean cop who won’t go with the program.

About: We got an interesting one this week. The DNA for today’s show is pure cable. It’s being put together by the same company that did True Detective. It’s a 10 episode anthology. Yet it’s going to be on NBC. Clearly, NBC wants to be cool again, so they’re trying something different (they were said to have gone after the project hard). But can a big network act like Netflix? Like HBO? Another cool aspect about this pilot is that it was written by a couple of unknowns. One of them drives an Uber. The other is a valet (shouldn’t this have been called “Carhunt?”). Unknown writers. Conservative networks trying to play cool. True Detective producers. This is definitely a project to keep your eye on.

Writers: Whit Brayton & Zack Rice

Details: 62 pages (undated draft)

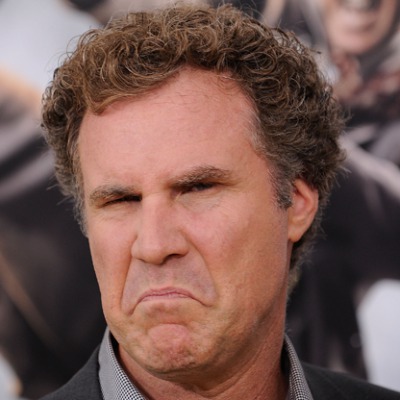

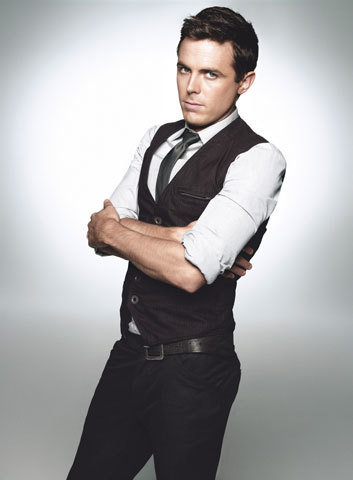

Ben’s little brother Casey is said to have been attached at one point but I think NBC wants bigger.

Ben’s little brother Casey is said to have been attached at one point but I think NBC wants bigger.

Uh-oh.

We got another show from the True Detective folks. We all know how I felt about that script (I was the lone dissenting voice). So today’s review comes with some baggage. I mean, if I hate it, that’s probably a good thing for the show, right?

But before we get lost in that argument, I can tell you that this is nothing like True Detective. Well, it is an anthology. So the whole thing will be wrapped up in one season. But this is way more mainstream. In fact, it’s ripped straight out of the headlines – the whole cop-on-the-run Christopher Dorner thing that happened in 2013 (strangely, this story takes place in 2013 as well).

The leniency with which cops can kill civilians and get away with it is a hot-button topic these days and Manhunt wants to bring that controversy to the screen in as exciting a way as possible. Let’s see how they do.

David Cofield may be the cleanest cop LA’s got. On this day, he’s part of a SWAT team led by brash commander, Warren Sutton. They’re going to invade some drug dealer’s home and, judging by the size of the team, it’s not some small fry.

The raid doesn’t go as planned and the dealers immediately start fighting back. One of them gets loose and Sutton chases him along a series of roofs. He finally catches him, but instead of cuffing him and letting justice decide his fate, Sutton kicks him off the roof, killing him. Several cops spot this, including Cofield.

Here’s where things get interesting. The other cops go on the record saying the dealer fell due to a struggle. But Cofield says uh-uh. Sutton clearly killed him. Cofield is visited by Internal Affairs, his lieutenant, his Captain, all who try to convince him to change his story. But Cofield is a good cop. He’s not letting anyone get away with murder.

A day after the murder, Sutton calls Cofield to meet and “talk.” The two convene at a late night diner, and the next day, Sutton ends up shot between the eyes. Meanwhile, Cofield’s on the run, going to the internet with his story. He explains what happened that fateful day, and insists that Sutton met with him to kill him. Sutton’s killing was merely an act of self-defense.

A third major character, Harry Drapkin, a once-great but now-fallen author, finds himself pulled into the case as Cofield’s only ally. In a world where the LAPD will be putting millions of dollars into discrediting and destroying Cofield’s story, Drapkin will be the only one who can expose the truth. But is his own legacy so tainted that no one will believe him? We’ll see!

I think Brayton and Rice are on to something here. I always found the Christopher Dorner story intriguing and was hoping he was going to expose this deep-set corruption inside of the Los Angeles Police Department. It was the kind of story made for the movies. Unfortunately, in real life, there are no happy endings. And whether that was because Dorner really was nuts or the corporation trying to take him down was too big, we’ll probably never know.

Either way, I do agree with Brayton and Rice’s decision to keep this story contained to 10 episodes. One of the big failings with television is that they push a story way beyond its lasting point (ahem – Prison Break?). Manhunt won’t have that problem. But what about the script? Is it any good?

It’s not bad. But man does it start off clunky. There are so many characters introduced in the first 10 pages that I almost thought someone was playing a joke on me. How do writers possibly expect us to remember six characters in two paragraphs? Ten in three?

A lot of these character intros come through the SWAT team, and I see this a lot when writers include SWAT teams or army platoons or any group of people. They name everyone. You don’t have to name every character if every character isn’t going to play a pivotal role in the story. Just name the key guys. Because besides the frustration of having to remember a bunch of people, over-introducing leads to confusion. With so many people introduced, I wasn’t sure who the main people were, forcing me to go back and re-read character introductions once I knew that Cofield and Sutton were the only two who mattered.

Once the pilot hits the midway point and we see where it’s going, though, we buy in. I’ve found that these “underdog fights against the corrupt establishment” stories almost always play well. They give us one of the most sympathetic characters on the screenwriting market – the underdog. And who doesn’t want to see a big corrupt establishment get exposed? That’s a great goal.

The writers add a couple of nice nuggets to the equation as well. It turns out that Cofield is being treated for schizophrenia. Also, we don’t see the exchange between Cofield and Sutton on the night Sutton is killed. This leaves some uncertainty into if everything went down the way Cofield said it did. And I think that’s important because if we know all the details from the get-go, the show is devoid of mystery. The big reason the Christopher Dorner case captured the public’s imagination was that we weren’t sure if he was telling the truth or not. We wanted him to be. But in the back of our minds we were thinking, “Errr… he kinda looks crazy.”

I have to say I’m excited by the recent explosion of the “Mid-Form” story (short form is movies, long form is traditional TV shows). One of the biggest weaknesses with movies is the inability to explore character. There’s only so much you can do in 110 minutes. With TV shows, by the second season, you’re often rehashing the characters in ways we’re already familiar with. An 8-10 episode arc seems like the perfect amount of time to tell a character-driven story.

And I like what the writers do with Cofield’s character. He’s got a restraining order against his wife and child – so something happened there. And he was recently suspended from the force for a week – another mystery that needs to be explained.

This is a good setup for a show. The only complaint I have is that it feels formulaic. I hated True Detective but the one thing I’ll give that show is that it was different. It took chances. And if NBC is going to go wrong somewhere in this search to be relevant again, it may be in that capacity. If they try to promote this as some big glossy companion piece to The Blacklist, it could get irrelevant fast. The whole advantage of an anthology series is that you only have a limited amount of episodes so you can take more chances. We’ll see if that’s in the cards, and where Manhunt goes from here.

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Because TV production moves a lot faster, you can rip stories straight out of the headlines. If you see something that captures the imagination of the country, consider writing a show about it. Remember, though, to optimize it for your storytelling needs. That’s the great thing about being a writer – you can do anything. So if the real-life story doesn’t end the way you wanted it to, or include the characters you think would best suit it, simply change it.

ATTENTION: THE SCRIPTSHADOW NEWSLETTER HAS BEEN SENT – Check your Spam and Promotions Folders if you did not receive. Hope you enjoy it!

Genre: Cray-Cray

Premise: When humanity discovers a human on Mars, they bring him home, where he learns all about the peculiarities of earth.

About: This adaptation of the classic sci-fi novel was written in 1995 specifically as a vehicle for Tom Hanks (this would’ve been right after Forrest Gump). The script was written by Dan Waters, who became a screenwriting sensation after the cult film everyone in Hollywood loved, Heathers. Waters wrote Batman Returns and Demolition Man in 1992, but has had trouble finding credits since (his most recent film is Vampire Academy). Paramount, who commandeered the project, seems set on bringing these old sci-fi novels to life, as they just bought the rights to The Stars My Destination last week (another Heinlein novel). Robert Heinlein is a legend in the sci-fi community, penning tons of books, including the sci-fi classic, Starship Troopers. Don’t tell Paul Verhoeven (who directed the film version of Troopers) that though. The director is said to have never read the book: “I stopped after two chapters because it was so boring,” he said. “It is really quite a bad book.” He later asked a friend to just explain it to him.

Writer: Dan Waters

Details: 156 pages! – 5/22/95 draft

Before you read this review I need you to go to Amsterdam, locate the nearest Mushroom store, and buy as many mushrooms as you can afford. Eat them. Then, and only then, will you have a chance at understanding this screenplay and my review of it.

I’ve read some fucked up stuff in my day. But this is the kind of script that makes David Lynch look like John Lee Hancock. I’m pretty sure I know why Tom Hanks passed on this. Because he couldn’t find a translator to make sense of it.

This is Birdman meets sci-fi meets Forrest Gump. Which may sound delightful to some of you. But I’m warning you. After you read this, there’s a 14% chance you may no longer understand the English language.

Stranger in a Strange Land starts when our first expedition to Mars ends in us finding a naked man running around the red planet with a bunch of rock monsters.

Mmm-hmmmm.

Okay.

The Marstronauts grab the human Martian, named “Mike,” and bring him back to earth. This new earth is very different from the earth we know now. While we no longer have war, the government’s been globalized, and radical religious leaders have become the most important figureheads on the planet.

A female reporter, Gillian, sneaks in to the hospital to get a story on Mike, then ends up stealing him and the two go on an adventure together. Where? To Jubal Harshaw’s house of course. Who’s that, you may ask? An ex ghost writer. And physician. And lawyer. Who now owns a hippy compound.

Sure. Why not?

What happens next? Well, by all measurable accounts , absolutely nothing for the next 40 pages. We just hang out at Jubal’s house where Mike, who speaks some gibberish form of English (“You happy me very,”) reads books and learns about humanity!

Eventually, a “sort-of” plot emerges where we learn that Mike’s parents, who owned a billion dollar corporation, died in a mysterious plane crash and the World Organization took over their company. With Mike being the son, he’s technically the heir to that fortune, which means the WO may have reason to turn him into rock food.

What happens next may or may not have something to do with group sex. And death. And people eating the dead. And speaking to people from the afterlife. I can neither confirm nor deny that there are three scenes that actually make sense in this script. Or that an ending that actually wraps things up exists. You will have to read the script yourself to find out. Please report back to me once you do. Insanity hurts.

I’m not going to lie. After finishing this, I wasn’t sure the writer had ever written a screenplay before. Or anything for that matter. If this was a menu, it would’ve started with the instructions for building a treehouse. And it would’ve been in Chinese.

As an experiment, I read five pages of this script out of order and then five pages in order. The five pages out of order made slightly more sense than the consecutive ones. Which should tell you what you’re in for here. Since it’s hard to know who’s responsible for the incomprehensible nature of the story, because I’ve never read the novel, I’ll just assume that both of these guys are off their rockers. I mean, who the hell were the people celebrating this novel when it came out? CIA-obsessed transients who mumble the ingredients of ketchup to themselves at the Santa Monica McDonald’s?

While I could probably key in on 184 things that were wrong with this screenplay, I’ll start with an obvious one. If you’re going to center a story around a man who’s supposedly different from everybody else, you probably don’t want to make everybody around him just as crazy as he is. By doing so, the character doesn’t stick out at all.

Indeed, Mike is swallowed up by this screenplay. In the first 70 pages, he gets about 15% of the screen time. Instead, we focus on hippy-extraordinaire, Jubal Harshaw, a name that could only have been conceived with the influence of at least a dozen hallucinogens.

And then there’s the structure, or lack there of. Look, we all know that books go on for longer than screenplays. This is why they bring in screenwriters to adapt novels and not novelists. Because screenwriters specifically know how to cut stuff down and focus on the things that matter. They know how to EDIT.

Dan Waters never got that e-mail. This is 157 pages of Wanderosa, heavy on the random. Why in the world would you write a 40 page sequence at a man’s house without a single plot point pushing the story forward? I can find absolutely no excuse for this.

The core of every screenplay is the character goal. It’s giving your protagonist something they’re after and then pushing them towards that something. If you don’t do that, you’re going to end up with a screenplay that goes nowhere – that lasts 157 pages. Even in the most optimistic scenario, where this is an exploratory first draft, there was no attempt by the writer to rein in this story at all.

And it doomed them. If you’re Tom Hanks and you read this, you see your character featured 5 times in 70 pages and you don’t start putting together notes for the next draft. You say, “See ya later.” You have to at least put the illusion together that you tried. Any schmoe off the street can write a bunch of random thoughts for 157 pages. Skilled screenwriters are the ones who can find the core of a story and build a structure around it.

Or maybe… maybe Waters knew this was doomed from the get-go. There is something in production circles known as “suspension of disbelief.” If the audience can’t get past the artificial reality you’ve created, it doesn’t matter what you write. Is there any scenario under which a naked man running around on Mars with rock alien brothers is going to work? Probably not. So Waters just said, “Fuck it. If I’m going nuts, I’m going nuts all the way.”

It just goes to show that some properties aren’t meant to be turned into movies. Although maybe this is another opportunity to explore angles, like we did last Thursday. Might the Scriptshadow community have an angle for Stranger in a Strange Land that actually works? Share your thoughts in the comments section. In the meantime, I’m going to go research lobotomies.

Script link: Stranger in a Strange Land

[x] what the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: For you writers out there who don’t believe in outlining, READ THIS SCRIPT. This is what happens when you don’t outline.

Scriptshadow readers try to sharpen their scripts before the Scriptshadow 250 Contest. Let me know what you think!

TITLE: Quilted

GENRE: HORROR COMEDY

LOGLINE: A 16-year-old neighborhood outcast must save his only ally, an anxious 7-year-old girl, from the supernatural entity, Vitadenghis, whom she has unwittingly summoned with toilet paper.

WHY YOU SHOULD READ: This script reflects my fears at the world of today. Come on, headlines are enough to make you shit in your pants. I wanted to take a few of those things, apply some good teenage angst and foible, lots of sexual innuendo, blood and fun and toilet paper. It has heart too, because I have a big heart too. I often receive the largest number of up votes on S.S with small vignettes I write about my life, but those vignettes are often morose, heart tugging things with little room for humor. I wanted to share something that might put a smile on someone’s face here. Let them save the lump in their throat for that special family’s member or their doctor. No lumps in this one, well, maybe at the end, or maybe I’ll be lumped into the scrap pile, but hopefully, someone will soften to it, give it a squeeze.

TITLE: Oakwood

GENRE: Western

LOGLINE: A grizzled alcoholic travels by hook or crook across the Old West to bury his brother but is hunted by those he’s wronged all the way.

WHY YOU SHOULD READ: Last time I was here, I was dominated by the Benny Pickles script “Of Glass and Golden Clockwork” and deservedly so. Despite not winning the coveted Friday slot, I was still given a TON of awesome advice on how to better my script (Monty), and was subsequently a Top 10% in the Nicholl Fellowship. Not huge accolades, but for my first screenplay? It felt good! — This is now my third script and I feel like I’ve gotten better since I submitted last. But this is a Western, damn it, and nobody wants them anymore. It truly needs to be the absolute best it can be to get any sort of traction. I really hope that the ScriptShadow community can help me again whether I move beyond AOW or not.

TITLE: Midnight Leather

GENRE: Psychological Thriller / Horror

LOGLINE: After a scandal leaves her hounded by the paparazzi, a grief-stricken actress tries to rebuild her life within the privacy of an isolated mansion that has a secret, and horrifying, past.

WHY YOU SHOULD READ: The Scriptshadow 250 Contest sounds AWESOME and I can’t wait to enter! But before I submit this script, I’d love to get it crowd-tested and work in a few more rewrites before the August 1 deadline. Midnight Leather is my sixth script, and it’s been described as psychologically dark, emotionally raw, and having a third act that will linger with you for the rest of the day. The female lead is actress bait for an A-lister looking for her BLACK SWAN, and overall, the script is in the same vein as SHUTTER ISLAND and THE OTHERS.

TITLE: Sugar Daddy

GENRE: Thriller/Drama

LOGLINE: An underachieving medical student gets embroiled in the dangerous world of organ trafficking when she accepts a scholarship sponsored by a conniving businessman.

WHY YOU SHOULD READ: I’ve always been a big fan of the May-December romance trope. Whether it’s Jane Eyre, Beauty and the Beast, Last Tango in Paris or My Fair Lady, there’s something that always draws me to the relationship dynamic between an older man and a younger woman. This fascination may even be part of the reason why Fifty Shades of Grey is currently in first place at the box office this week. — So imagine if you could get your hands on a script that contains a lead pair with a similar relationship dynamic and a suspenseful plot set in a cut-throat (literally) and grizzly world where nobody has a moral compass. Imagine a script that’s as sexy as it is intelligent and thought provoking. That is ‘Sugar Daddy’ in a nutshell.

TITLE: INDIANA JONES AND THE STONE OF DESTINY

GENRE: ACTION ADVENTURE

LOGLINE: Memories of an artifact from Indy’s past begin to resurface as the famous archeologist searches for the greatest legend in history, the lost city of Atlantis.

WHY YOU SHOULD READ: The Indiana Jones character is at a crossroads. While fans and professionals bicker back and forth on whether or not to reboot the franchise or let Harrison Ford have one more shot, time for one of those scenarios is quickly dwindling. I believe I have written a great script that has just the answer – why not do both? — I attended film school at Columbia College before transferring to USC. I never finished. Instead I started working in the restaurant business, and I now own a catering company for private jets. But I never stopped writing. See what you think.