Genre: Comedy/Period

Premise: A 1950s Hollywood fixer finds himself on his first job he can’t fix – the star of the studio’s biggest movie ever is kidnapped by a group of communists.

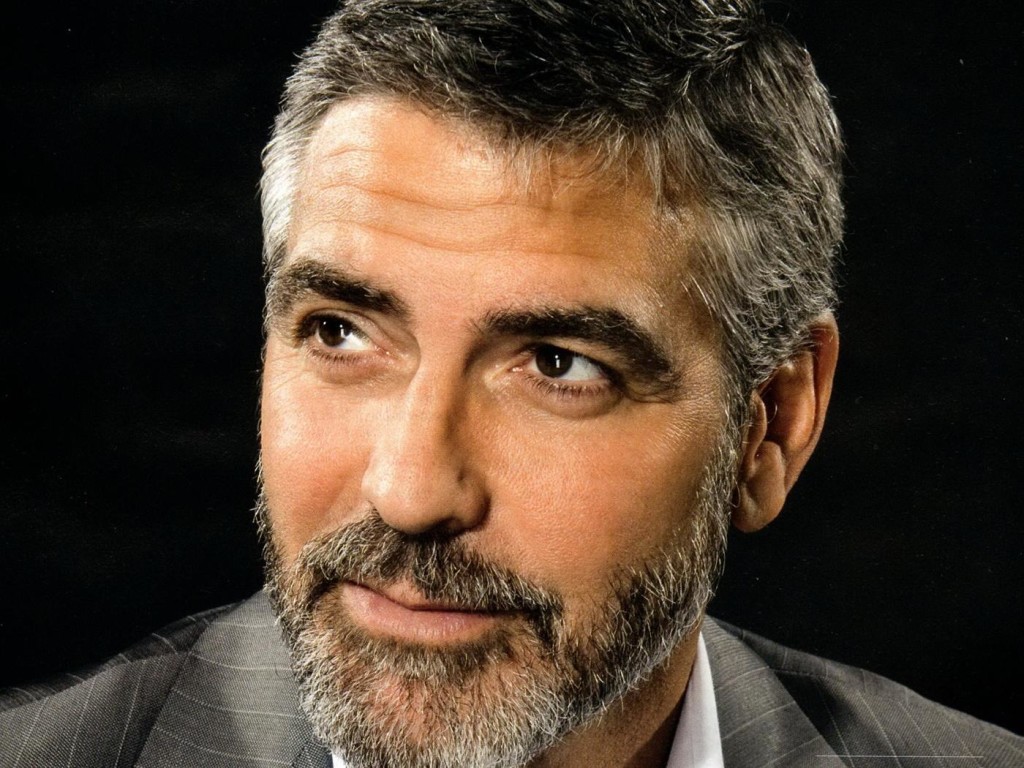

About: This is the Coens’ next movie. As you’d expect, actors are lining up in the hopes that the brilliant character-building brothers can put them in a position to win an Oscar. So this film is stacked. It will star Scarlett Johansson, Channing Tatum, Josh Brolin, Jonah Hill, Tilda Swinton (who it should be required is in every weird movie from here on out until the end of time) and, of course, George Clooney.

Writer: Joel & Ethan Coen

Details: 111 pages

There’s this rumor going around that I don’t like any movies/screenplays that don’t fall under the traditional safe Hollywood paradigm. This rumor started because I hated scripts and movies such as Upstream Color, Inside Llewyn Davis, Somewhere, and Winter’s Bone.

But it’s simply not true. I like plenty of indie movies. I enjoyed Blue is The Warmest Color, Silver Linings Playbook, Black Swan, Rushmore. What I don’t like is bad storytelling. And because indie film is a place where filmmakers take more chances, the results typically play at the ends of the spectrum, which leads to extreme reactions. So when I don’t like something, I really don’t like it. Inside Llweyn Davis still leaves a bad taste in my mouth. I mean you had the biggest asshole main character of the past decade in a movie without a plot.

And that’s what I don’t get. The Coens are always at their best when they’ve got a good plot going. The Big Lebowski, No Country, and Fargo all had big plots thrusting the story forward. Inside Llewyn Davis had… a lost cat. That was the plot.

And you know what? I don’t even require a plot to like a movie. I need a plot OR great characters. Just one of the two. Like Swingers. Swingers didn’t have a plot. But the movie had great characters, so you enjoyed the ride.

Which leads us to today’s script, the Coens’ latest. And I can start off with some good news. This one actually has a plot. Is that plot any good? Well, let’s take a trip into the Coen Brain Collective (bring any drugs you can locate within the next 10 seconds) to find out.

Eddie Mannix is a fixer. Hollywood in the 1950s is a lot like Hollywood today, with one major difference – it was easier to control the image of its stars. Which was important. Because studios used to OWN stars back then. There wasn’t any of this “free agency” shit. A studio had you under contract. So if you drank a lot, got arrested a lot, were gay, backed up your files on icloud – it was in their best interest to keep that information out of the papers. And that’s where Eddie Mannix came in. He was the master at getting rid of these problems.

Until this movie of course, when something goes horribly wrong. Mannix’s studio loses the star of its latest Ben-Hur-like film, “Hail, Caesar!” Baird Whitlock is yanked off the set by a bunch of commies, which was a really bad thing to be back in 1951 in Hollywood. These Commies, who happen to be screenwriters, are pissed! They’ve been writing all these movies for Hollywood, but other writers are getting the credit (hey, how is that any different from today?). So they do the obvious thing to enact revenge – they kidnap Baird and demand 100 thousand dollars from the studio (which I’m assuming was a lot of money in 1951).

As word starts to leak out that Baird may have been kidnapped, Mannix must work the phones to keep all the gossip columnists from publishing the story in tomorrow’s paper and ruining his studio’s investment forever. This little event also threatens to rekindle an old rumor of Baird’s that has plagued him since he first got into the business. We’re talking about the “On Wings as Eagles” rumor, which is something so big, so dark, that even Richard Gere would find it disturbing. Mannix has certainly got his work cut out for him. Can he save the day one last time? We shall see!

Let’s start out with the good. This is a lot better than Inside Llweyn Davis. It’s actually fun. In fact, it’s closest in tone to the Coens’ Big Lebowski. Unfortunately, it doesn’t have the same super memorable characters as Lebowski. Eddie Mannix is a wild-eyed work-hound, but I’m not sure I know anything about him beyond that.

Traditionally, we get to know the main character in a screenplay, understand the flaw holding him back, empathize with him, sympathize with him, hope that he changes, and that’s really why we go along for the ride. We’re rooting for this person to become better and succeed.

The Coens’, as you know, don’t always subscribe to this approach. Their characters have great big flaws, but those flaws aren’t always figured out. Look at The Dude in The Big Lebowski. His flaw is obvious. He’s a lazy irresponsible bum. He has no initiative and does nothing in life. In a normal movie, we’d watch as The Dude realized this, and eventually learned to take initiative.

Instead, The Dude keeps on being The Dude at the end. He’s The Dude. Nothing’s going to change about him. The question is, why does this work when every screenwriting book in the world tells you your main character has to have a flaw and that, over the course of the movie, they must overcome that flaw? It works because The Dude is also one of the most lovable characters ever created. Which means, purposefully or not, the Coens’ are drawing on one of the oldest screenwriting tricks in the business. They made their main character super-likable. And sometimes that’s enough.

Conversely, this is why, I believe, Inside Llewyn Davis didn’t catch fire with the public. The main character was a huge dick. Maybe this would’ve worked had Llewyn showed growth. Audiences have proven with movies like Groundhog Day that they’re willing to watch a dick if he shows signs of improving. But Llewyn never did.

If you’re going to give us an asshole character AND they’re going to remain an asshole character throughout the movie, fuggetaboutit. I mean the Coens are so amazing at creating secondary characters that they can keep their movies at least watchable (John Goodman and Justin Timberlake were great in Llewyn Davis), but in the end, it’s that protagonist who’s either going to lead you to the promised land or not.

Which brings us back to Hail Caesar. Eddie Mannix was so busy running around saving everybody else’s ass that I never got to know him. So I never really cared. And the more I thought about it, the more I realized the Coens missed a major opportunity in connecting us and making us care about Eddie. Eddie didn’t have a major relationship in the film. He never had a girl he liked, a family member he wasn’t getting along with, an important friendship or work relationship. He didn’t have that one thing that got us into his head. Again, look at The Dude. He had Walter (John Goodman). That was the entryway into The Dude’s mind so we could get to know him. That wasn’t here with Eddie. And it really hurt the screenplay. I mean how many screenplays survive when you don’t feel like you know the main character afterwards?

So despite having a few fun moments, Hail Caesar was a bit like a runaway chariot race. It eventually went scurrying off the tracks.

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: The hero’s key relationship in the story (girl, family member, friend) is one of the easiest ways to get the audience into the hero’s head. It’s through dialogue with these characters that we get to see your hero’s problems, his worldview, his flaws, his fears, his dreams, his insecurities – all the things that make him him. If your main character doesn’t have anyone to talk to, it’s going to be really hard for us to connect with him.

What I learned 2: Frack for drama! Never forget the importance of stakes for your main character. If there aren’t major consequences for your hero failing, you’re only mining a fraction of the drama you could be in your movie. The Coens, who are usually pretty good with stakes, had none here for Eddie (another problem with his character). I didn’t get the sense that he would be in any trouble if he didn’t find Baird. We needed that scene where the big scary mobster-like studio head took Eddie aside and said, “This is our biggest movie ever. I don’t want it to bomb because you didn’t do your job. You know what happens to people who don’t do their job, right Eddie?” And that’s all we needed.

Note: The Newsletter has JUST BEEN SENT OUT. Check your spam and promotions tabs if you didn’t receive it. E-mail me at carsonreeves1@gmail.com if you didn’t get it. If you want to be on the newsletter, you can sign up here.

This week’s amateur picks are linked below. Offer your constructive criticisms and then vote for the best one of the bunch in the comments!

TITLE: Spooked

GENRE: Horror-Comedy

LOGLINE: Two slackers with dead-end jobs try to turn their haunted past into reality TV stardom.

WHY YOU SHOULD READ: This was my first attempt at writing a feature-length screenplay and it became a Finalist in the 2013 PAGE International Screenwriting Awards. It also garnered a Fresh Voices nomination for “Best On Screen Chemistry.”

I’m not a comedy writer, but always thought ghost hunting shows lent themselves naturally to humor because

they take it so seriously — just like my protagonists.

After a year of rejections, I feel like I’m ready for whatever reaction you (and the SS community) can offer. Plus, I’m more

than a little annoyed about a recent TV web series springing up with the same name and subject matter. What

do I have to lose now?

I should also note, that a certain character quirk was written LONG before I ever watched Zombieland. (It took me a while

to get this one finished.) And I think my version plays out funnier anyway.

My 2nd feature is in a completely different genre (historical fantasy) and took 6 months of research/developing, 1 month to write. It’s currently placed as a semi-finalist for this year’s PAGE Awards.

TITLE: NERVE AND SINEW

GENRE: Action Thriller

LOGLINE: When an ex-UFC fighter reluctantly accepts a kidnapping job from the Russian mob, he sneaks into an upscale apartment complex to capture the target but finds himself in a high intensity hostage situation when armed terrorists simultaneously take over the building in a Mumbai-style attack.

WHY YOU SHOULD READ: Been hacking away at this craft for several years now. Have written several scripts, read countless others. It can be a frustrating grind — writing scripts and trying to find success with them. Sometimes I’d love to quit. But I just can’t. Nothing else even remotely interests me the same way.

This is a classic blood-pumping action thriller with a modern touch that should be a fun ride if it ever makes it to the screen. But don’t take my word for it. One reviewer had the following to say: “Although there are big budget explosions and gun fighting scenes, the script never feels cliche in its execution of plot. It doesn’t lean on the violence and pays close attention to staying original and dark throughout. This could be a big, blockbuster film that would attract a broad audience and potentially an A-list actor.”

Also, it’s a quick 105 pages with sparse, vertical writing. At the very least you won’t get a headache reading it.

It’s done well in contests (initial draft was top 15% in Nicholl) and on the Black List (revised draft recently received an overall rating of ‘8’), but I’d love to get it some more exposure. The more eyes on it, the better, right?

TITLE: THE SANDMAN

GENRE: period thriller

LOGLINE: In 1940’s LA, an orphan young man must unravel the mystery of “The Sandman” – a legendary lost film – before the beautiful blind girl he loves falls victim to the sinister forces who seek it

WHY YOU SHOULD READ: because it is a story for anyone who loves movies with a passion and finds in the cinema not only escape from life but life itself. If a young Dickens or Poe would have written a script in collaboration with Roger Ebert, I’d like to think they would come up with something like this.

TITLE: Goodnight Nobody

GENRE: Contained Thriller

LOGLINE: Besieged by “monsters” that have emerged from their toddlers’ closet, a couple must keep their wits about them if they hope to escape their house alive.

WHY YOU SHOULD READ: Whenever you read in a release from a prodco that they may have independently developed a similar idea, I’m the guy they’re talking to. Ten years ago I wrote a script about a lonely boy whose stuffed animal comes to life, and is still around when he’s an adult. I’m not saying that I was ripped off – my script would never have been in the same zip code as Seth McFarlane to have even seen it – but I had a similar idea once upon a time that just didn’t find its way up the chain despite my manger-at-the-time’s best efforts. Five years ago a script I wrote with a partner generated a little heat. It was a reinvention of the King Arthur saga. Then three other Arthur scripts sold before we could cash in on that heat. Our script withered on the Hollywood vine and died. This summer I almost sold a script to “Lifetime”, but turns out they had a too similar project already in the works. And, just this week, “Pivot” sold which has a very similar idea to a sci-fi spec I wrote earlier this year, so it’s another labor of love I get to throw into a drawer. I just need my luck to change. I always feel like I’m on the precipice, and just need to figure out what it is that’s holding me back. Maybe you guys can help me figure out what that is.

TITLE: Hellscape

GENRE: Horror

LOGLINE: When a teenage Scout troop becomes lost in the Utah desert, they experience terrifying hallucinations that point to a supernatural stalker.

WHY YOU SHOULD READ: Hellscape was actually inspired by a real-life event. A few years ago, I learned about a group of Boy Scouts who found themselves in a brutal heat wave while hiking the Grand Canyon. Before long, they were suffering bizarre, disturbingly realistic hallucinations. And that’s when the idea struck me – what if those hallucinations were something else, something paranormal? What better place for demonic mind games than a sweltering, Mars-like wasteland far from civilization?

Get Your Script Reviewed On Scriptshadow!: To submit your script for an Amateur Review, send in a PDF of your script, along with the title, genre, logline, and finally, something interesting about yourself and/or your script that you’d like us to post along with the script if reviewed. Use my submission address please: Carsonreeves3@gmail.com. Remember that your script will be posted. If you’re nervous about the effects of a bad review, feel free to use an alias name and/or title. It’s a good idea to resubmit every couple of weeks so your submission stays near the top.

Genre: Action/Thriller/Comedy

Premise (from writer): A team of disabled vets reluctantly reunite when their former commander drops a bombshell on them: the terrorist who caused their disabilities is in America to pull off a devastating attack, and they’re the only ones who can stop it.

Why You Should Read (from writer): It’s a 2014 Page Awards Semifialist, a 2014 Creative World Awards Quarterfinalist, and it made the top 15% of 2014 Nicholl fellowships. There’s a wide array of reactions to the script, and I’m really curious at to what the SS readers (and you) will say. As for the script? Action galore, fast-paced, complex female characters, wild twists, dark humor, and a strong theme. Oh, yeah, GSU up the wazoo.

Writer: Will Hare

Details: 107 pages

In the comments section of this batch of Amateur Offerings, readers remarked about a few of the entries gaining traction on other sites (being optioned, finishing in the semi-finals of contests, and in the case of Will Hare, having an indie movie probably going into production). The general consensus was, “Wait, if a guy doing this well has to come to Scriptshadow to still get help, how hard is it out there?”

It’s hard. Will has done great. He keeps writing and he keeps hustling and getting this far is a huge achievement. But people finishing high in contests and waiting for their first indie movie to get made are still a far ways away from being able to make a living at screenwriting. Heck, I know people who’ve sold scripts for 6 figures who are now back in their home towns bussing tables.

That’s why I don’t have any qualms putting these “higher amateurs” in the mix for Amateur Friday. You’re a struggling writer until you start getting consistent work. And for those who think it isn’t fair, my message is simple. Write a better script than these guys. If you’re going to compete with people like Travis Beachem and Dan Gilroy, you first gotta beat the guys finishing in the semi-finals of big contests (and actually, the guys who are winning those contests). So bring it!

It’s 2008. Afghanistan. Tough guy Major Fenton leads a group of young soldiers with cool nicknames (Gurps, Pops, Coldbeer, Sanjuro, Ikiru) into an Afghanistan town. Everything seems to be going fine as they drive up, until an evil female terrorist named Afshoon appears amidst the dust. Before they realize they’ve been ambushed, a firefight begins.

Cut to six years later and that government who so dutifully called for their services no longer seems to give a shit about them. Pops is missing a leg and has agoraphobia. Coldbeer (a female) has begun an online service focusing on physically abusing deadbeat dads. Sanjuro is still reeling from her sister’s death on that fateful day. And Gurps is in a mental ward sucking down Dr. Feelgood pills.

But when Fenton finds out that Afshoon has snuck into the U.S. and is preparing for an attack bigger than 9/11, he decides to get the band back together for an impromptu terrorist assassination, so the people of this country can finally see the group for who they are, heroes.

Of course, not everything goes as planned. Their journey takes them from Deadbeat Dad organizations to drug warehouses to The Taste of Chicago to the streets of Philadelphia. When it’s all said and done, will they kill the terrorists, save the United States, and become heroes? Or is this group destined to be a band of clueless misfits forever?

Berzerkers was kind of like if you took the sequence from “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest” where the mental patients go on a boat trip, combined that with Rush Hour 2, then dropped that combo into the F5 tornado from “Twister.”

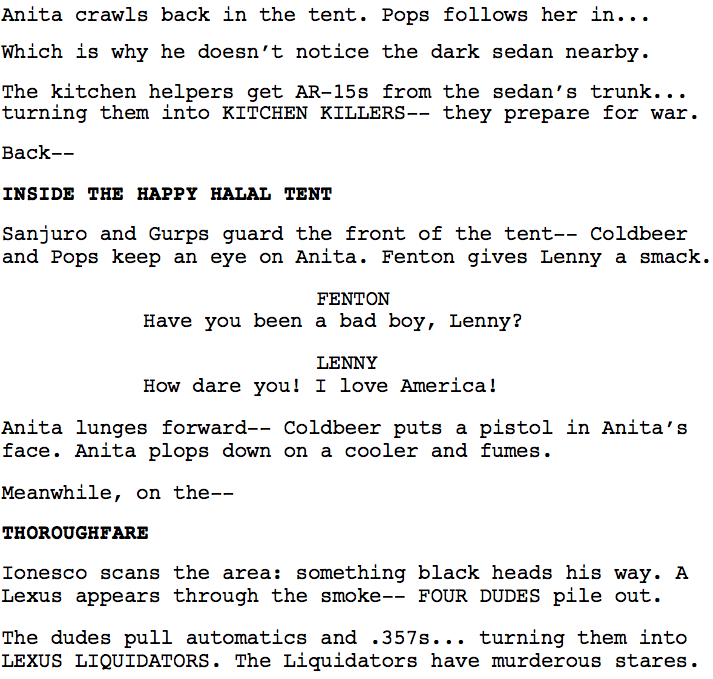

I will give Bezerkers this. It lived up to its name. This thing was NUTS! There is more shit packed into this script than any script I’ve read all summer. You gotta be on your game when you pick this thing up because it bombards you with information. Here’s a typical page from Berzerkers:

Let’s count all the elements on this page.

1) Anita

2) Pops

3) AR-15 guns

4) A sedan

5) Kitchen Killers

6) Happy Halal Tent

7) Sanjuro

8) Gurps

9) Fenton

10) Lenny

11) A cooler

12) Thoroughfare

13) Ionesco

14) A Lexus

15) Four dudes

16) 357s

17) LEXUS LIQUIDATORS

This isn’t even a full page, actually. It’s ¾ of a page. And there are 17 elements to keep track of! Imagine trying to juggle that many things in your head for an entire script. I was trying to keep everything straight but by page 20, I was doing that thing where I would get down the page and realize I didn’t remember anything I just read. So I had to go back and reread it again. And once I did this 5 or 6 times, my brain called “Uncle.” It needed out.

So I enacted my “Tough Cookies” policy. This is where if I don’t understand something or if I’ve made it halfway down the page and realize I haven’t grasped any of what I just read, I don’t go back and reread it. I charge forward.

My logic for this is that it’s the writer’s job to make it easy for me. It’s not my responsibility to want to read something. Of course, once you reach the “Tough Cookies” point, you’re only grasping a portion of what you’re reading, and by the time I reached the end, I didn’t know what 30% of the stuff being mentioned was. Maybe more.

This brings up an important question. How much information is too much information? How many characters can there be? How many plot twists? How many villains? How much jumping around? How extensive can the protagonist’s plan be? How crazy can each scene get?

Unfortunately, it’s not as simple as finding a number. The number of elements a reader allows correlates directly with how well you’re telling your story. Is the concept intriguing? Do we like the characters? Are the scenes exciting/fun? Is the story fresh/original? Is the dialogue strong? The higher you rank in all of these categories, the more leeway the reader’s going to give you as far as complexity.

And if you step back and look at the individual elements in Bezerkers, there’s definitely some good stuff going on. I like the idea. I think it’s funny. Some of the characters are well-conceived (Pops, an agoraphobic amputee). There are a lot of female characters in traditionally male roles, which was nice to see. It’s just that when crammed together along with all this other stuff, those little gems got buried.

One of the pieces I think was misconceived was the opening. It goes by way too fast. We know these characters for all of two seconds. They come upon some silhouette of a person in a dust storm. Somehow they know this is an evil enemy of theirs. Then, bam, the scene is over and we cut to present day. What?? The scene’s over before it began!

Sometimes, in our desire to get to our story as quickly as possible, we speed through important early scenes. This opener should’ve been milked. Get to know all these characters so we like them. Don’t just have them shooting the shit either. Give them choices to help define their characters for the audience (a driver can either go towards two sketchy looking men or take the long way around them – this would show whether he’s brave or a coward).

Then put us in that town and have the characters do whatever they’re supposed to do there (deliver supplies?). Build tension as we sense something is wrong. Some of the soldiers start to get worried. A few of them float the idea of ending the delivery early and heading back to the Humvee. But it’s too late. It’s a trap. And at the center of the trap is our villain, Afshoon, who we should get to know way more extensively in this version. This way, we feel like we know who these guys are, so when they get the band back together, we care about these folks.

I just want to conclude this by saying I love Will’s hustle. I love that he keeps writing and networking and pushing his work out there. That’s what you gotta do. If you keep doing those things, sooner or later it WILL pay off. And finally, I just want to part with this Pixar quote, yet again, since I keep seeing writers make this mistake: Simple story – Complex characters.

Script link: The Bezerkers

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Do not shorten an opening scene (or any scene for that matter) just to meet some beat sheet page number. If your scene needs time, it needs time. Would the famous opening scene from Inglorious Basterds have worked had it only been two pages? No. I think the opening scene in The Bezerkers needed that extra time to build tension and suspense, as well as to introduce us to everyone.

Writer Joseph Gangemi is debuting his new show “Red Oaks,” on Amazon today. Red Oaks is produced by Steven Soderbergh and the pilot was directed by Pineapple Express director David Gordon Green. It’s about a tennis pro’s crazy adventures back in the summer of 1985. As some of you know, I used to support myself by teaching tennis, so I couldn’t resist getting Joe in for an interview. What transpired was a full on course study in how to get into television writing. So any screenwriter looking to break into TV is going to want to take notes. Also, you can check out Joseph’s show on Amazon right now! For free!

Rising star Craig Roberts (Submarine, Neighbors) plays the lead in “Red Oaks.”

Rising star Craig Roberts (Submarine, Neighbors) plays the lead in “Red Oaks.”

SS: Hey Joe. Why don’t we start off with you letting us know a little about who you are and how your writing career came about.

JG: Sure! I’ve been a member of the WGA since ’97 when I sold my first spec to New Line. That same year as luck would have it I also sold my first novel, which I’d written with a friend back in college and that had been sitting in a drawer for years. (It was eventually published under a pseudonym, so don’t bother Googling!) The serendipitous sales of novel and spec enabled me to quit my day job in corporate America and turn to full-time writing. It’s helped that I’ve done it from Philadelphia, where the cost of living is lower than LA, and where there are fewer distractions. (Though my agents and manager are constantly after me to relocate.)

Since then I’ve worked for most of the studios on open writing assignments, published another novel—this time under my actual name—and had two of my specs reach the screen, WIND CHILL, which starred Emily Blunt and came out in 2007, and STONEHEARST ASYLUM, staring Kate Beckinsale, Michael Caine, and Ben Kingsley, which will be released this October 24th (Shameless plug!) In that time I also began writing for TV, and to date have sold three projects, including “Red Oaks.”

Television is a really appealing medium for a writer, and especially a novelist. Whenever my writer friends bemoan the shortening of attention spans and the death of the novel I point out that audiences still seem just as addicted to long, sprawling, episodic storytelling as they did in the Victorian era when the novel was born—they’ve just embraced a new delivery system. Not that novels and episodic TV offer identical experiences; but I do think they offer audiences some overlapping pleasures, like immersion in richly populated worlds thick with subplots and digression, a greater sense of the passage of time, etc.

So I didn’t need much arm-twisting to try my hand at TV. Also, TV is enjoying a golden era akin to that of indie movies in the ’90s—it’s the place where offbeat storytelling is still welcome, where niche audiences are cultivated and anti-heroes celebrated. Whereas the economics of filmmaking and especially marketing have forced the studios to narrow their offerings to a specific bandwidth, namely tent poles and those few high concept comedies that can withstand translation into other languages.

I sold my first TV pitch to Lionsgate and ABC seven years ago. It was called “The Lodge” and was a haunted hotel show. Unfortunately like a lot of pitches it didn’t survive the development process—an all too common case of seller and buyer not realizing until too late what kind of show we were making. (I thought it should be “Twin Peaks,” they wanted “Fantasy Island.”)

Eager not to repeat the experience, I decided with my next TV idea—another hour-long drama called “Strega,” which is a kind of male “Rosemary’s Baby”—to once more write it on spec. “Strega” had a lot of heat in the marketplace and eventually sold to ABC-Signature, where it’s now in the process of being packaged before being shopped further. (TV can be confusing because the studios are free to develop shows for other places besides their parent networks, hence the reason an end card on an NBC show might read “CBS Studios.” Studios produce TV shows, which are then licensed to networks for broadcast; it’s akin to how movies are made by studios and then licensed to theaters. The big difference being that in TV the networks weigh in creatively during development.)

When I was approached about “Red Oaks”—a show I sometimes half-jokingly describe as “‘Caddyshack’ with tennis”—I decided again to write the pilot on spec, in part because I was co-writing with a friend I’d never collaborated with before (Greg Jacobs, whose life story loosely inspired the show). But also because I was switching genres and needed to prove to myself I could write funny.

SS: As is always the case when I bring writers in, I’d love to know how you got your agent.

JG: I came by my agent in an unusual way. (Though the more breaking-in stories I hear the more I think there is no “usual” way.) Around ’96 a novelist pal of mine, Jon Cohen, invited me to tag along on a trip to LA, where he was meeting about a spec screenplay he’d just sold. (Jon would go on to write “Minority Report.”) Over dinner one night I met his agent Howie Sanders, who, upon learning I was a published short-story writer and aspiring screenwriter, graciously offered to read anything I might submit. When I got home I promptly FED EX’d him a romantic comedy spec. He called to say “I can’t break a new writer in with a romantic comedy—” Things were very different in ’96!—”but you have talent and you should write a horror movie or a thriller.” Since I liked horror (my first, pseudonymous novel was horror and eventually won a Bram Stoker Award for best first novel) I pitched him a few ideas. He responded to one, which I proceeded to outline and write and sent back to him for notes. We went back and forth for about six months, fine tuning to get it ready for the marketplace. Howie went out with it in October of 1997 and sold it to New Line. Which is what earned me my WGAE card— and Howie a place in my heart!

SS: Amazon has a unique way of creating pilots. Can you tell us how their system works?

JG: At the networks, cable channels, HBO, etc., pilots are only ever seen by executives and the occasional focus group, and all decisions about series orders are made behind closed doors, in corporate boardrooms. Amazon makes its pilots public, basing its series orders on the number of customer views, reviews, and five-star ratings, as well as chatter on social media. And just to clear up a common misconception, you don’t need to be an Amazon Prime subscriber to stream these pilots—anyone can go to the Amazon site now and screen “Red Oaks.”

What’s appealing about this model for a writer is that if you make an Amazon pilot you at least know your friends and family will get to see it. Which with networks is only the case if your show gets ordered to series and put on the schedule. There are many pilots that have been made but shelved, regardless of cast and pedigree. For instance HBO’s pilot of Jonathan Franzen’s bestseller “The Corrections,” starring Ewan McGregor. Also with the Amazon process at least you can sleep at night knowing you got your story “out there” where it can live or die based on its own merits and not whether it fits some corporate mandate at one particular moment in time. (“We need more shows that appeal to high earning males age 24-42.”) So there’s a meritocratic element that’s unique.

SS: And what was the process of you selling your script to Amazon? How did that happen?

JG: Greg Jacobs and I first met when he directed my spec “Wind Chill” (a spec co-written with my pal Steven Katz.) In addition to being a director Greg is Soderbergh’s longtime producer—in fact he won an Emmy last year for producing “Behind the Candelabra.” For years Greg has been regaling us with funny stories about his summer job as an assistant tennis pro in suburban New Jersey. When Soderbergh started getting involved in TV, he encouraged Greg to develop a show based on his misadventures, and Greg suggested bringing me in to help write it—because I’m a buddy, but also because I could bring some outsider perspective to the material and help transform autobiography into good drama. We outlined, which is where all the heavy lifting is really done, and then began passing a first draft back and forth until all parties felt it was ready to package with a director. David Gordon Green responded very quickly, and with him attached, we began shopping it.

SS: For the newbies here, can you talk about how the traditional pilot system works, so we can get some context?

JG: Summer is “pitch season.” In June you partner with a like-minded producer to pitch your project to studios, in hopes that one will take a shine to it and take it off the market with some sort of financial deal. At which point your new studio backer takes the lead in shopping the project in order to “set it up” at a network. As with spec scripts, the more competitive the interest in a project, the more likely you can get a more lucrative or desirable outcome. For instance you’ll often read in the trades that a hot project got a “put pilot” commitment from a network, which means that the deal struck carries a hefty penalty that the network must pay if they decide not to order the pilot. And every year there are a handful of direct-to-series orders, where a show’s creator is guaranteed his or her full writing/producing fee for X number of episodes (usually 12, or half of a network season) regardless of whether they are made and aired. Often this occurs when the creatives behind a show are household names, like David Fincher (“House of Cards”) or Soderbergh (“The Knick.”) But occasionally it happens with an unknown, as it did recently with Mickey Fisher and “Extant.”

If you sell a pitch in the summer, you spend the autumn going back and forth with the network, studio, and producers getting notes on the outline. Then around November 1 you finally get the go-ahead to start “writing pages,” with a goal of delivering the best draft you are capable of producing no later than the Christmas holidays when all the network execs jet off to Aspen. You sweat bullets throughout January, and then around February everyone holds their breath and hopes theirs is among the projects ordered to pilot. If you are among the lucky ones you make your pilot in the spring and deliver it in time for the “up fronts” in New York, when the networks begin touting their new shows to advertisers. Then around June you either get a series order, or go back to square one and start over.

The above is only for network development. AMC, HBO, Netflix, Amazon, etc., aren’t tied to the calendar and therefore have no official pitch season. Theirs is more like the “rolling admissions” policy of some universities.

SS: What do you think is the key to not just selling a pilot, but getting it on the air? Is there a formula for that?

JG: That’s the problem with a lot of network programming. It’s formulaic. (e.g. Legal Thriller; Forensic Procedural, etc.) Which is why so many of the cable shows are eating the Nets’ lunches and stealing their Emmy’s. Not to mention their viewers. And network execs—who are not dumb—realize this, and are trying to develop material that feels more “cable-like.” Darker themes. Anti-heroes. Period pieces.

SS: I’m curious about the financials for television. How much does a writer a) get paid for selling a pilot, b) get paid for being staffed on a high-rated show (Scandal) and c) get paid for a smaller show (like, say, Teen Wolf).

JG: There are guild minimums for every format and length of show—that’s the baseline. How much more you make for writing a pilot depends on (a) your quote (if you’ve sold pitches or been hired to write teleplays in the past), and/or (b) how much competition there is among interested buyers. A ballpark number I’ll throw out there for, say, an hour long network drama (because Guild rates differ depending on whether a show is network or cable) that isn’t subject to a bidding war could be around $90,000, give or take. This is called the “guarantee,” meaning the studio guarantees to pay you this much for your writing services provided the project is “set up” at a network, and regardless of whether the script is ever ordered to pilot. Once you get a pilot order, additional fees kick in—perhaps a production bonus, definitely some sort of producing fee. Remember in TV the writer-creator is also typically a producer. Often an Executive Producer (the highest position in TV credits.)

I’ve never been on a writing staff so it’s more difficult for me to give sample numbers. But back in the 90s I was invited to audition for the writing staff of one of the later seasons of “The X-Files,” and I recall being offered a contract that guaranteed me a certain amount per week for six weeks, after which the producers had the option of extending my employment for the rest of the season. And I think at the time I did the math and figured out I would have made about $125,000 if they kept me around for a full season. Which isn’t chump change by any stretch—especially if you are single, with no dependents, as I was at the time. But since I was only guaranteed six weeks of employment I concluded that it wasn’t worth uprooting and relocating to Los Angeles. So I politely declined. And heard that the producers—who were riding pretty high in the ratings then—were flabbergasted and outraged.

SS: If you’re a young writer who wants to get into TV, in your opinion, what’s the best route to take?

JG: As with features writing, there’s really no one best route—many roads lead to Rome. Take my friend Ben Cavell. He went to Hollywood with one spec script in hand (a cop show set in 19th century Boston, and this was back before period pieces were in vogue) and a single well-reviewed short story collection, and managed to land an entry level staff job writing on “Justified.”

My point is, talent and perseverance will pave just about any path you choose into this industry.

That said, writing a spec pilot of an original idea—as opposed to a spec episode of a show already on the air—seems like the best way to get noticed. Even if the show itself isn’t commercial or viable, the fact that you chose the tougher challenge of world-building shows people that you have moxy.

SS: And how do you get on to a writing staff? I have a talented writer friend who wants to get on a staff and learn but he has no idea where to even start.

JG: There’s a good piece on this subject in Mike Sack’s recently published book “Poking a Dead Frog: Conversations With Today’s Top Comedy Writers.” It happens to be by my TV agent Joel Begleiter, who talks about the pros and cons of writing an original versus a spec episode. He also gives some good advice on how to get the attention of guys like him, at big agencies like UTA.

I’ve heard that there are junior positions on writing staffs where you are called something like “story editor” or “writer’s assistant” or somesuch, where you can learn the business and eventually graduate to full-fledged Writer. But I’m not sure what qualifications you’d need to get those jobs. But a snappy spec pilot couldn’t hurt!

SS: What is the TV world looking for right now? Does it vary because there are so many outlets? Or is there a particular type of show that’s hot (aka – a show like Breaking Bad)?

JG: At present I’m hearing that the market is oversaturated with procedurals, that “light hour longs dramas” (think “Desperate Housewives”) are out of vogue, and that “noisy” dramas—the higher concept the better—are what execs are hungry for.

Also, genre is white hot. Nine out of ten genre shows are performing well, and in the case of “Game of Thrones” and “Walking Dead”—spectacularly so. (“‘Walking Dead’ is doing ‘ER’-in-the-’90s numbers internationally,” an exec gushed to me recently). Of course writers have to be smart—it makes no sense to pitch a vampire show when there are so many already on the air. And I would think it would be hard to do a high fantasy in the long shadow of the juggernaut “GoT” unless it’s based on a piece of fancy IP (Intellectual Property in Hollywood-speak) like Terry Brooks’ Shannara series or Anne McCaffery’s Dragonriders of Pern sequence.

SS: You’ve written features as well. Is that a world you’re still interested in? Or are the opportunities so good in TV right now that it’s not even worth it?

JG: I remain very interested in features and in fact Greg Jacobs and I have a film adaptation of Castle Freeman’s novel “Go With Me” that starts shooting in November. The screenplay form is so difficult to crack, and so satisfying when done well, that it presents an irresistible challenge I don’t think I’ll ever entirely master or get tired of tackling.

Writing for TV scratches a different creative itch and presents a different set of challenges—plotting out season-long story arcs, stage-managing a large cast of characters, evoking the passage of time, etc. Also, as you might guess, the sheer volume of writing a typical network requires to fill its schedule means there are that many more job opportunities for the working writer trying to maintain his WGA health coverage! And besides the networks there are countless cable channels, premium channels, subscription services like Netflix and Amazon and Hulu, websites like Funny or Die and emerging platforms like Xbox TV—all of which are hungry for content.

From an economic standpoint also TV is a sector of “showbusiness” that far outstrips boxoffice earnings. In my friend Lynda Obst’s book “Sleepless in Hollywood” (an essential state-of-the-industry book that should come shrink-wrapped with every newly issued WGA card) she points out that TV contributes nearly ten times more revenue to a studio’s bottom line than do feature films.

It reminds me of a time I was on the Fox lot to see a film exec friend. En route from the parking structure I noticed a huge new building being built across from the historic old Hollywood (and somewhat shabby) film building where I was headed. I asked my film exec friend about the new building and he gave a weary sigh and said, “That’s the new Fox TV building… that ‘The Simpsons’ built.”

SS: Wait, so you’re saying that a movie like The Avengers doesn’t make nearly as much money as, say, Gray’s Anatomy?

JG: Yeah, it kind of blew my mind too to learn that TV revenue so far outpaces film. Now I’m not sure if that includes ancillary income from things like Avengers lunch boxes and back packs. It might just be box office and DVD / download revenue (on the film side) versus licensing and syndication fees (on the TV side). But according to the numbers Lynda quotes in her book, TV generates ten times the revenue. Crazy. But maybe not when you consider that a hit show like “Walking Dead” is being viewed by something like 50 million people a week, worldwide. Can you imagine how valuable a show like that is in syndication? Not to mention the money that studios make spinning off international versions of hit American shows. “CSI: Moscow.” “The Office: Brazil.” Keep in mind also that American audiences only go to the movies on average a few times a month. (If that.) Now think about how many hours of TV the average viewer watches per week.

I don’t want to send your aspiring screenwriters scrambling for the exits, or turn them into TV converts. But I think there’s no reason they shouldn’t open themselves to alternate forms of storytelling. That’s a good career move in general. Not to mention a good way to keep yourself creatively engaged over the course of a career. I’d recommend writing novels as well. And graphic novels if you are so inclined. Hell, even videogames if you have the opportunity. It’s all storytelling, and makes you a better rounded storyteller.

SS: And finally, since Red Oaks is about tennis, which do you think is harder? Winning a point against Rafael Nadal or selling a pilot script?

JG: That’s a tough one! Though I can say facing off against Soderbergh in a notes meeting is equally intimidating.

Busier than normal here at the household. One of the Dragon Gods of Screenplay Heaven got sick and I had to take him to the vet. So I’m reposting my newsletter review of BIRDMAN, which is from a long time ago. Now since that time, they’ve come out with a trailer. And I’ll be the first to admit, the trailer looks awesome. It’s unique in all the right ways. It takes chances. It’s fun. But I’m not backing off my review. The script was borderline unreadable. And I know my review was a little mean-spirited, but as I know all of you can attest to, there’s nothing that gets you more riled up as a reader than a comedy where nothing is funny. Now whether this is another case of a “what the hell did I just read” turning into True Detective, we’ll have to see. But it’s pretty easy to come up with a cool looking trailer that then becomes a terrible movie. Heck, we see it every month. I’m hoping I’m wrong though. I’m hoping Inarritu had some vision that went beyond the script, which can sometimes happen with writer-director projects. So here’s my original newsletter review of Birdman. Also, I WILL be sending out a newsletter later this week. If you’re not on the list, you can join here.

Genre: Comedy

Premise: A famous director turns away from his successful blockbuster movie franchise to try and make it on Broadway.

About: “Birdman” is Alejandro Inarritu’s first foray into comedy. He’s best known for his dark gritty dramas like 21 Grams, Amores Perros, Biutiful, and Babel. Birdman is finished filming and stars Edward Norton, Michael Keaton, and Naomi Watts. Now, Inarritu actually has a little bit of history with the screenwriting world. He used to work closely with writer Guillermo Arriaga on all his films. Then Arriaga, a screenwriter through-and-through, began a personal campaign pushing the agenda that writers and directors should share an “auteur” credit in every movie, as they are just as responsible for the movie as the director. That pissed Inarritu off, who strongly disagreed, and the two’s friendship and working relationship fell apart as a result. This happened during the writing of Babel, and the two haven’t worked together since. It’s an interesting development in that one could argue that Biutiful was Inarritu’s worst film, and it was his first full movie without Arriaga. Coincidence? Maybe the script for Birdman, which Inarritu is the head writer on, will help us find out.

Writers: Alejandro G. Inarritu, Nicolas Giacobone, Alexander Dinelaris, Armando Bo

Details: 121 pages (Sept 10, 2012 draft)

I’m always interested when someone who’s successful in one arena tries to break out of the hole they’ve been pigeoned in (get it! “Birdman!”) into another arena. Not only is there the curiosity factor of if they can do it, but there’s a lot on the line. Everyone’s doubtful that you can pull it off, and they’re kind of ready to rip you apart if you fail. And there’s no genre harder to pull off than comedy.

So to hear that Inarritu was making a comedy – he being responsible for some of the most depressing films of the last decade – well, I’d be lying if I said I wasn’t surprised. Did Inarritu have a secret life? Did he stay home late at night watching Chris Farley movies and making farting noises with his armpit at the dinner table? Or was he just sick of being tabbed the super serious guy? Or better yet, did he just want to prove he could do it? These were questions I was curious to have answered.

Our oddly named hero, Riggan, is a 55 year old director whose successful film franchise “Birdman,” has made him a household name. But when given the chance to make a fourth Birdman film and add even more money to his coffers, Riggan decides, instead, to try out Broadway – to make a serious dramatic play which will bring him the respect he’s always longed for.

The problem is, he hates his lead. Which is a huge issue when your play debuts in a couple of weeks. Luckily, that lead gets injured, and Riggan is able to replace him with a hot Broadway actor named Matt Skinner. The Brando-like Skinner may be a better actor, but he’s also nuts. He lives and breathes his characters, and isn’t afraid to fuck with the production in order to get what he wants. For example, one day he sets fire to the set. Why? Cause he’s Matt Skinner!

If Riggan only had to worry about Matt, he MIGHT be able to get through this. But he’s also going a little nuts (he constantly talks with a manifestation of his Birdman character throughout the movie). He’s got a daughter who hates him, seemingly because he doesn’t know what Twitter is. And there are numerous cast and crew members who are banging (or wanting to bang) each other, inadvertently destroying this delicate production Riggan’s worked so hard to create. Will Riggan figure out a way to save his play and finally earn the respect he feels he deserves? You’ll be able to find out this fall.

Okay, I’m just going to come out and say it. This was terrible. I mean, it’s pretty much a failure on every level. This is a comedy without any laughs. The tone is all over the place (dead serious one moment, overly goofy the next). And I’m wondering if the script’s shortcomings are an ESL issue. Because very little made sense. I know I couldn’t write a comedy in another language. So there’s no shame in it. The shame is in trying to do something you shouldn’t have done in the first place.

Birdman’s problems go deep. Within the first 5 pages, I was confused. First of all, the main character starts in his dressing room, then walks out onto a stage, where the other characters are having a discussion about a psycho ex-boyfriend, which we believe to be a scene rehearsal. But then they turn to Riggan and ask him, mid-rehearsal, what he thinks about the matter. He says something to the effect of, “I don’t know the guy so I don’t know,” and we begin to think that maybe this isn’t a rehearsel. That it is, in fact, actors talking before rehearsal.

But then later in the conversation, Riggan gives one of the actors an acting note preceded by the parenthetical (as the director). Oh! I guess Riggan is the director now. Nobody told me that. Guess we were supposed to figure it out on our own. Except then we realize that Riggan is both the director AND the lead actor. So now I’m going back to the beginning and trying to figure out what this means. Was this a rehearsel or actors chatting? If it was rehearsel, why is the director AND lead actor not out there rehearsing with them? If it wasn’t a rehearsal, why is Riggan giving directing cues mid-coversation?

I see amateurs make this mistake a lot but rarely pros. Whenever you’re setting up a complicated situation (a writer-director you haven’t set up yet walking into an ambiguous scene), it’s your job to identify that it might be difficult for the reader to interpret and call upon your clarity wand to clear things up. Tell us Riggan is both the director and the lead actor in a description paragraph if you have to. Confusing a reader right off the bat in a screenplay is one of the worst things you can do. They lose trust in you and the script IMMEDIATELY and from that point on, you’re playing catch-up with their trust.

On top of this, it’s never clear if Riggan was the director of his famous franchise, Birdman, or the lead actor. He’s portrayed as a director in our story, so we naturally assume he was the director of Birdman. But then it’s indicated he ACTED in those movies too. This is so unnecessarily confusing. Why not just go with one or the other?

I loved Amores Perros. It made me an instant Inarritu fan. Babel had some really great moments in it as well. So I’ve always had a soft spot for Inarritu as a director. But comedy is not his forte. I respect stepping out of your comfort zone. But I mean… yikes. This is not funny or good or clear or anything that a screenplay needs to be. It wants to be five different movies instead of one. I mean, not even the basics are in place. There are no stakes! What happens if our main character, who has hundreds of millions in the bank, fails with this play? He goes back to making Birdman 4. Nothing is lost. Nor are we ever told what this play is about. This is a movie about a play and I don’t know what it’s about!

The only cool thing about this script is that Michael Keaton is playing Riggan – Keaton, of course, of Batman fame. There’ll be some nice irony here in that he’s basically playing a version of himself. And I see that Inarritu is doing a little auto-biographicalizing of his own. He’s trying to get some demons about the business out – how does one be a successful artist and balance family at the same time?

I like when writers bring their own problems into their characters as that’s usually when we see the deepest most meaningful exploration of character. Unfortunately, there was nothing authentic about the Riggan-daughter relationship. I don’t know. It was just… off. Her big monologue in the movie – the one that breaks down their relationship with one another – amounts to “You need to use Twitter more!” Does any of this script make sense? Or more importantly, has nobody told Inarritu that his script isn’t any good?

I think there needs to be a system in place where production companies and studios send their scripts out to a neutral party – someone who has zero skin in the game. Because a lot of money is about to be spent. Don’t you want someone telling you if your script is terrible? Don’t you want that chance to avoid a colossal mistake? Or to fix what’s broken? I get the feeling this script was written in a vacuum and these guys didn’t have anyone telling them how off it was.

Then again, it’s a comedy. And comedies are easy to hate if you’re not “getting” the sense of humor. So maybe I’m just not getting it. Also, the movie starts out with Michael Keaton floating in mid-air and never goes on to explain why. With a universe that untamed, maybe this isn’t the kind of script meant to be judged. Maybe you’re supposed to throw logic to the wind and just go with it. But there’s a fine line between that kind of movie and one that throws a bunch of nonsensical crazy shit at the screen and hopes it hits. Let’s hope Birdman isn’t the latter.

[x] what the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: If you want to go “off the reservation” with your script, like Birdman, go ahead and do it. But please take the time to be clear about what’s happening on the page. The wilder your story is, the less reference we have to draw on, which means we need more hand-holding along the way. If we’re confused about something as simple as what your hero does, that can kill the entire reading experience.

What I learned 2: When you write a dialogue scene, try not to think of it in terms of what you (the writer) need to do with the plot. Think of it in terms of what the characters need. This is a common mistake all writers make. We’re so focused on moving the plot forward or getting in those important lines of exposition, that we forget that in real life, there’s no all-knowing entity sitting above people forcing them to do anything. In real life, people just talk. So you kind of have to take yourself out of the equation and approach the scene from inside the two characters. They’re not thinking about what you, Aaron Sorkin, need them to say so he can properly pay off that first Act setup. They may just want the girl across from them to know that they like them. If you do this properly, your scenes will stop feeling stagey and plot-driven and start to feel more like two people actually talking.