Search Results for: scriptshadow 250

Genre: Romantic Comedy/comedy

Premise: (from writers) When a slacker is dumped mid-proposal at a musical version of Pride and Prejudice, he enlists the help of his best friend to go back in time and kill the one person they hold responsible for his girlfriend’s high ideals: Jane Austen.

About: Every Friday, I review a script from the readers of the site. If you’re interested in submitting your script for an Amateur Review, send it in PDF form, along with your title, genre, logline, and why I should read your script to Carsonreeves3@gmail.com. Keep in mind your script will be posted in the review (feel free to keep your identity and script title private by providing an alias and fake title). Also, it’s a good idea to resubmit every couple of weeks so that your submission stays near the top of the pile.

Writers: Howard Dorre (story by Andy Kimble and Howard Dorre)

Details: 112 pages (This is an early draft of the script. The situations, characters, and plot may change significantly by the time the film is released. This is not a definitive statement about it a little buggy out there is the project, but rather an analysis of this unique draft as it pertains to the craft of screenwriting).

Previously on Scriptshadow: Some months ago a writer e-mailed me frustrated that a script titled “F*cking Jane Austen” had made the Black List. That’s because he and his partner had written a script with almost the exact same premise. Adding insult to injury, he read the other script and felt it wasn’t as good as his own. It was a bold claim. Writers often believe their scripts are better than the stuff that sells. So he put his money where his mouth was, issuing a challenge. Have me review both scripts and decide which was better.

So yesterday I reviewed the Black List script, F*ucking Jane Austen, which, in a nutshell was well constructed but too generic. Today I’ll be reviewing its amateur doppelgänger, Killing Jane, and deciding once and for all who owns who in the First Annual Jane Austen Back In Time Romantic Comedy Smack Down.

Much like yesterday’s script, it all starts with two twenty-something slackers. We have Pan, a Hometown Buffet Assistant Manager, and we have his best friend, Jared, who is some sort of assistant scientist.

Also much like yesterday’s script, Pan is dumped by the girl he thought he was going to spend the rest of his life with. At first the openings were so similar, and so common to this genre, that I began to question whether any writer in the romantic comedy genre aspired to be original anymore. But the more I thought about it, the more I realized this was about Jane Austen, noted for her books about love and romance. So I suppose it makes sense that the movie starts with a girl dumping our hero. Still, I would’ve preferred something a little more original.

Anyway, Pan becomes convinced that the reason his gf left him was because she, and all women for that matter, had developed unrealistic expectations of men that could all be tied back to Jane Austen and her ridiculously gooey novels about love and romance.

So Pan and Jared get to talking and realize that the best way to take care of this problem is to go back in time and kill Jane Austen! Well lucky for them, Jared has access to a time machine prototype at the lab!

So they take the time machine back where they immediately run into Thomas Lefroy. For non-Jane Austen historians, this was Jane Austen’s one significant lover. Thomas just so happens to be on his way to a ball, where he plans to court – who else but… Jane Austen! Our not-so-heroic duo joins him, and pretty soon they’re at an actual ball where the infamous Austin is socializing. Maybe this hit won’t be as difficult as they thought.

Now you have to remember, Jane hasn’t actually written any novels yet, so she’s sort of a nobody. That makes priority number one finding her. So Pan starts chatting up some hottie in a coreset bad mouthing Austen at every turn, only to find out that he’s actually talking to… Jane Austen!

Now Pan didn’t expect Jane to be hot so this is throwing off his game. Jared just wants to kill the bitch and go home but the more Pan talks to her the more he kind of likes her. Lucky for them, they’re able to cajole their way into staying the night, and that allows Pan even more access to Jane. He uses this time to share with her his “thoughts” about things that will be available in the future, and she’s so taken by his “imagination,” that she quickly falls for him.

But just when we think nobody’s getting killed, Lefroy comes along, pissed that this Pan fellow has stolen his lady, and starts devising a plan to shorten his life expectancy by about 250 years. Pan and Jared must get back to the future just to stay alive, but then what happens to Jane? Will Pan ever see her again?

If you were comparing both of these scripts just on the craft, yesterday’s script would come out on top. It’s way more polished. Take Jared being a scientist for example. Whenever you create a time travel script, how you approach sending your characters through time often tells a seasoned reader how dedicated you are to your premise. If you throw something lazy in there, that tells them that you’re not exerting 100% effort. If you come up with something inventive however, that tells us you went that extra mile and are serious about your screenplay. Jumping back in time via a DeLorean is unique. Jumping back in time via the intestines of a rhinoceros is unique (from the recently reviewed Past Imperfect).

Making the best friend character a scientist with access to a time machine is probably one of the laziest options you could come up with. Not only that. But Jared was introduced, in the flashback scene, as the “cool kid.” That means making him a scientist is not only lazy, but inconsistent with his character.Yesterday’s choice was no home run either, but this option felt particularly convenient.

This was followed by a dreaded celebrity cameo with David Hasselhoff. I’m not going to call the celebrity cameo a death knell because as we’ve seen, a lot of professionals use it. But I will tell you this. David Hasselhoff has appeared in more comedy scripts that I’ve read than I have fingers. So again, you have another unoriginal choice, giving me the impression that you’re not trying hard enough.

What I quickly realized was that while yesterday’s script was too uptight, this script was too loosey-goosey. It was almost the exact opposite in that sense. But here’s where things get interesting. Because this script wasn’t so locked down on rails like yesterday’s offering, the writers were able to take more chances. And while those chances didn’t always pay off, they made the script more interesting, less predictable, and funnier.

Maybe the humor in this one just suited my taste better but when Jared busts out “Ice Ice Baby” on the piano at the ball, I was definitely laughing. And when Pan accidentally walks in on Jared (earlier in the script) potentially masturbating to Dora the Explorer, I nearly lost it. It just seemed like these two had fun with the premise and weren’t afraid to let their hair down. I think that’s one of the challenges but necessities of comedy. Yes you have to have to structure. But if we don’t feel like you’re enjoying yourselves and having fun with it, then the comedy isn’t going to play.

But when I really decided I liked this script better was around page 75, when we jump back into the present. In yesterday’s script, I always knew exactly what was going to happen and when it was going to happen. I was shocked here then that we jumped back into the present with so much time left. I just had no idea where that would go and I’m not saying it was the most amazing choice in the world. But the fact that it was a choice I wasn’t expecting exemplified why I preferred it. Because the writers weren’t so locked down in story beats and act markers, the story unraveled in a more organic and engaging manner.

Now a huge issue that I’m sure a lot of you are going to bring up is the difference in the premises. In yesterday’s premise, the goal was to have sex with Jane Austen. In today’s script, the goal is to kill Jane Austen. I’ll tell you right now. Having your goal in a comedy be to kill someone is always a bit of a risky venture. I know they just did it in Horrible Bosses, but they really made those bosses evil and therefore almost deserve what was coming to them. This is Jane Austen we’re talking about. She hasn’t done anything to anyone. So producers are going to have a tough time with that, as they’ll be afraid your heroes will come off as unlikable from the get go.

Now personally, this kind of premise doesn’t bother me. I think it’s kind of funny actually and reminds me of the more cruel minded films of the 80s like Throw Mama From The Train. I also think that it’s part of what makes this treatment better than yesterday’s. The writers are willing to take more chances and be a little more daring. But this really bothers people for some reason so you may have to rethink that.

Despite all this praise, I still can’t recommend Killing Jane. The recklessness of the storytelling definitely leads to a lot of funny moments, but craft-wise this script is far from where it needs to be. Take Pan for instance. He spends a lot of time trying to convince Jane to be a writer, something that at this point in her life, she’s doubting she has the ability to do. But the scenes are empty because there are no stakes on Pan’s end of the conversation.

Let’s contrast that with Back To The Future. There’s a nice little scene in the middle of the movie where Marty is talking to his dad at high school and realizes he’s writing something. He asks him whathim and his dad says a science fiction novel. Marty laughs and says, get out of here. I never knew you did anything creative. He then asks if he can read it. His dad says no, because if someone else read his work and didn’t like it, he didn’t know if he could handle that kind of rejection. The scene works because Marty is also pursuing something in the arts. He wants to be a guitarist – a rock star. But he too is afraid of putting himself out there. So there’s something personal in the exchange for Marty. Not just the father.

So if I were writing Pan, I would probably give him some artistic ambition and put him at a turning point in his own life. He’s been given an opportunity to take a stable well-paying job in the “real world,” or he can keep pursuing this artistic endeavor, even though there’s no guarantee it will pay off. Now when he talks to Jane about continuing her writing, there’s something at stake for Pan because he’s going through something similar in his own life.

So I feel like these guys still have a ways to go in terms of learning the craft but I did like this better than F*cking Jane Austen and for that reason Killing Jane wins the First Annual Jane Austen Back In Time Romantic Comedy Smack Down!!! Congratulations guys. :-)

Script link: Killing Jane

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Your script isn’t dead if a similar idea gets purchased. The sell gets tougher, but there could always be another company out there who wants to make the same movie. Your idea really isn’t dead until that similar project goes into production. So it’s your job to monitor sites like Deadline Hollywood and IMDB Pro and pay close attention to those projects’ status. Because if you wait until the movie comes out before you find out, you might have just wasted eight months of your time working on a dead man walking script. This is why information is so crucial to every screenwriter.

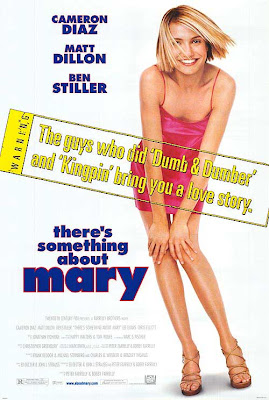

It’s Comedy Theme Week everyone. For a detailed rundown of what that means, head back to Monday’s post, where you’ll get a glimpse of our first review, Dumb and Dumber. Tuesday, I took on the best sports comedy ever (yeah, I said it), Happy Gilmore. Wednesday was Grouuuuuundhog Day. Thursday, Wedding Crashers. And for our final film of the week, one of my favorite comedies ever, There’s Something About Mary!

Genre: Comedy

Premise: 15 years after a horrifying prom night accident, a man decides to take a second shot at the girl he fell in love with. Only problem is every other man in the world wants her too.

About: The movie that propelled cinema into a decade of gross-out humor (some of which is still going on today), There’s Something About Mary became a sleeper hit back in 1998, bringing in 176 million dollars at the box office. In one of the best known gags in the film, where Mary erroneously mistakes Ted’s semen for hair gel, Cameron Diaz was said to have fought the gag ferociously. Her argument (which was rather sound if you think about it) was that a woman on a date would be checking herself constantly, and therefore would never have her hair like that. The Farrelly’s finally convinced her to give it a shot, and we subsequently got one of the most memorable moments in film history.

Writers: Peter and Bobby Farrelly

There’s Something About Mary is in my top 3 comedies of all time. The structure, much like the Farrelly’s other movie I reviewed this week, Dumb and Dumber, is all over the place. But the reason this film makes you laugh is because it has some of the best comedy set pieces ever written. And it’s a testament to how finicky comedy is, because I’ve seen the Farrelly’s create countless set pieces since then that just weren’t funny. And that’s one of the reasons I wanted to revisit this classic. I wanted to figure out what made this one different.

First, the structure. Again. Three words. “What the hell?” This is a really oddly-structured film. The movie places its first act in the past, establishing Ted and Mary’s relationship as teenagers. It then spends its entire second act with the two apart. I want you to think about that for a second. A romantic comedy (which is what this essentially is) keeps its two leads apart for the entire middle portion of the movie. What the hell?

It gets weirder. We started off with Ted as our main character. But the middle act actually switches over and makes Mary the main character, occasionally giving the spotlight to Healy (Matt Dillon’s private detective villain). So the entire middle act is dedicated to a relationship which isn’t the main relationship in the movie. The main relationship, Ted and Mary, doesn’t get kickstarted again until the final act! That’s when Ted arrives in Florida and makes his move on Mary. The third act then becomes its own little romantic comedy, with the traditional, “Guy gets girl, guy loses girl, guy gets girl back.” With montages and everything!

So why does it still work? Well, I think I know. All of the guy characters in this movie have incredibly strong goals: “To get Mary.” That drive means that it doesn’t matter whose story we jump to, because when we get there, that storyline will have intense forward momentum driven by that character’s pursuit of that goal (Mary). Also, through it all, the story’s driven by our ultimate wish, to see Ted get Mary. In fact, outside of When Harry Met Sally, I don’t know of a comedy or romantic comedy where you want the two main characters to get together as much as this one.

And I think that’s a huge part of why the movie works. There’s Something About Mary spends the first 90 minutes of its running time building up Ted’s attempt to get Mary. Remember how yesterday I said the reason Wedding Crashers was weak was because the stakes were low? Well here, the stakes are as high as they can possibly be. The reason we care so much in the last 30 minutes is because we’ve just spent the entire movie watching Ted go through hell and back to get to Mary. This build-up is what makes their scenes together so captivating. Because they’re packed with the tension of “Will this work out? Does he finally have her?” Go back and watch that scene where Ted first meets Mary again. In that 3 second moment after Mary responds, “Didn’t we just do that?” to Ted’s asking her if she wants to get some coffee and catch up, I can’t remember a time in movies when my heart sank that much. And it’s all due to the buildup of stakes.

Attention to stakes is also the key to one of the most famous comedy scenes ever, when Ted gets his balls stuck in a zipper. The reason this scene works so well is not because, “Wowza! His nuts are stuck in a zipper!” It works because for the last 20 minutes, the writers have built up that this is the single most important moment in Ted’s life. Somehow the nerdiest kid in school has pulled off the impossible – he’s taking the prettiest girl in school to the prom (stakes)! We are on pins and needles begging that this works out. So when it starts to backfire, and when that fateful zipper moment comes, and we’re hoping and praying he somehow fixes it in time to still go to prom. When it doesn’t? And the situation continues to get worse instead? It breaks our heart. Because we know this is it. You don’t get a second chance to take the prettiest girl in school to prom.

The scene also does double duty, creating a key residual effect. That terrible situation he went through? That losing of the chance to go out with the most popular girl in school? It makes Ted the single most sympathetic character in the world. I mean we’ll go anywhere with this guy after that. And so when we learn that he’s going to take another shot at Mary, even if he’s going about it creepily and hiring a private investigator? We don’t care. Because we believe he deserves that shot. And whereas yesterday the goal of getting some random girl at a wedding made Wedding Crashers’ driving force weak, the pursuit of the perfect girl who you lost out on when you were in high school because of a freak accident…that goal is about as strong as they come.

I want you to think about that because it’s an important screenwriting lesson to remember. What happens if Owen Wilson loses that girl? Let’s see. He loses out on a girl he’s known for all of 24 hours. No offense but: BIG FUCKING DEAL. He’ll get over it. But with Ted, this is the girl he’s spent every day for the last 15 years thinking about. It’s personal. There’s history there. If he loses this girl, you feel there’s a good chance it will destroy him for the rest of his life.

The Farrelly’s, like Happy Gilmore, have also created a great villain. Unlike the one-dimensional forgettable villain in Wedding Crashers, Tad Healy has a ton going on. He’s smart. He’s funny. He’s slimy. He’s good at what he does. This is what I mean when I say, “Add some dimension to your villain.” Again, you could’ve just made him a great big asshole. But Healy is much more than that, which is why his character is so memorable.

Another thing I like about the Farrelly’s comedy is they always ask the question, “How can we make this worse for the character?” And when you do that, you usually end up with something funnier. So in the scene where Healy drugs the dog so it likes him and impresses Mary, they say, “How can I make this worse for Healy?” Well, what if the dog died? So now the dog’s dead. And now Healy has to do the whole “CPR” bit on the dog and bring it back to life before the women come back in the room. You see this device being used again and again throughout the movie, especially on Ted, and it’s a big reason for all the hilarious set pieces.

But I think the thing that sticks out to me most when breaking down this film, is how wonky that structure is. The Farrellys have really weird structures to their films. Just like Dumb and Dumber, we have our heroes starting in one place, driving to another, and then beginning a relationship in the final act. But Mary is even more complicated, since the second character (Healy) is our villain, and isn’t with Ted on his trip. Therefore you have this cross-cutting storyline going on in the second act where we’re jumping back and forth between Ted’s journey and Healy and Mary’s courting. I have to admit, it’s different from any comedy plot I’ve read, and I get the impression that Peter and Bobby haven’t ever looked at a manual on how to structure a screenplay. This is why Dumb and Dumber and Mary feel so fresh. They don’t go how you think they’re going to go. However, before you jump on that bandwagon, it’s important to note that this seems to hurt them just as much as it’s helped them. They have some dreadfully unfunny movies in their vault, many of which peter out near the end (Stuck On You, Me Myself and Irene, and The Heartbreak Kid), and a lot of that is structure-related.

Lots of other things to take away from this movie. I didn’t get the chance to show, once again, how much effort the Farrellys put into making you love their hero (he befriends the retarded brother. He wants to help out Mary even after learning she’s 250 pounds and in a wheelchair), but I think it’s safe to say that a big part of the formula for their success is making sure you love and root for their protagonist. I also thought this was one of the few “romantic comedies” to create a fully rounded female character. She was maybe a wee bit on the wish-fulfillment side (she loves sports, likes to hang with the guys, doesn’t care about looks) but Mary is definitely different from every other romantic comedy lead female you’ve seen. There’s Something About Mary is one of those few screenplays that takes chances, breaks the rules, and those changes actually end up making the final product better. I can’t tell you if this happened on purpose or by accident. All I can tell you is that it worked.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[x] genius

What I learned: KYFC! Know your fucking characters! I’ve been encountering this a lot lately in the amateur screenplays I’ve been reading. Writers aren’t thinking about their characters! They don’t know what their character does for a living, what their passion is, what their dreams are, what their vices are, what their bad habits are, what they like in the opposite sex, what their education is, what state they grew up in. I used to be of the opinion that this stuff didn’t matter. I’ve done a 180 on that and let me tell you why. I’ve realized that a lot of boring dialogue comes from the fact that the writer doesn’t know enough about the character who’s speaking that dialogue. When you don’t know that person, you give them generic lines. Let me give you an example. There’s a moment where Mary’s roommate, the old woman, asks her if Matt Dillon, who she’s going on a date with, is cute. She replies, “He’s no Steve Young.” Now this is by no means an earth-shattering line of dialogue. However, it’s a line of dialogue that could only come from Mary herself. It’s a line of dialogue that tells us a lot about who Mary is (she likes football – which is also established earlier in the screenplay when she’s telling Ted about her love for the 49ers). Without knowing that Mary is a woman who loves football and the 49ers, we may have heard a more generic response such as: “He’s all right I guess.” That’s a line that anybody in the world could’ve said. It’s generic and uninteresting. And the less you know about your characters, the more lines LIKE THAT are going to come out of your characters’ mouths. Add enough of them up, combined with enough lines from other characters who you don’t know well, and the more non-specific lacking-of-insight boring generic dialogue you’re going to get. So people, please: KYFC!

What I learned from Comedy Week: In 4 out of 5 of this week’s comedies, the writers went out of their way to make their characters sympathetic. Loving the characters may not be a requirement (you don’t love Phil in Groundhog Day), but in comedies, it helps a lot. Also, in 4 out of 5 of the comedies, the characters had incredibly strong goals. I can’t stress this enough. The more your hero wants to achieve his goal, and the bigger and more important that goal is, the better your script is going to be. It’s no coincidence that the script with the weakest central goal (Wedding Crashers) was also the weakest of the comedies. Outside of that, the rules are fairly wide open. Just try to keep the stakes up, not just for the film but for the set pieces and individual scenes as well. Add multiple dimensions to your villain to make him memorable. And make sure your concept is funny to begin with! Any other trends you guys caught from this week’s entries, please include in the comments section! :)

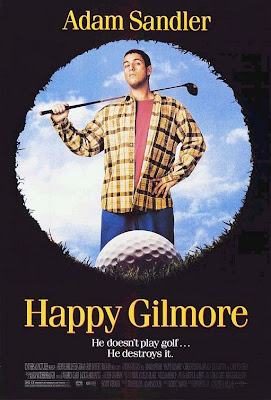

It’s Comedy Theme Week everyone. For a detailed rundown of what that means, head back to Monday’s post, where you’ll get a glimpse of our first review, Dumb and Dumber. Today, I’m taking on the best sports comedy ever made, Happy Gilmore.

Genre: Comedy

Premise: A failed hockey player is forced to join the pro golf tour in order to save his grandmother’s home.

About: As not many people saw Adam Sandler as a movie star at the time, Happy Gilmore did only so-so at the box office, taking in 38 million dollars. The movie, however, would later become a huge hit on video and help propel Sandler into becoming one of the highest paid actors in the world. Roger Ebert said of Sandler’s performance at the time, which he did not like, that he “doesn’t have a pleasing personality: He seems angry even when he’s not supposed to be, and his habit of pounding everyone he dislikes is tiring in a PG-13 movie.” As I find Sander’s anger to not only be the funniest part of the film, but an integral part of his character and character arc (and thus organic to the story), it just goes to show how polarizing reactions to comedy can be!

Writers: Tim Herlihy and Adam Sandler

Leave it to Adam Sandler to restore some normalcy to the craft of screenwriting.

Uhhhhh….what?? Did I just mention Adam Sandler and screenwriting in the same sentence? And that sentence didn’t include the words “dreadful,” “incomprehensible,” “horrifying,” “unreadable,” or “brain-cancer-inducing?” I believe I did. Yes, believe it or not, before Sandler and his “writing team” began invading our cineplexes with movies like “Has-Beens Hanging Out At A Cabin” or whatever the hell that piece of crap was with him and Chris Rock and Kevin James, he actually made a few good movies. And Happy Gilmore, by a country mile, was the best of them.

While yesterday’s comedy made all sorts of funky structure-breaking choices that confused and confounded me, Happy Gilmore is one of the most straightforward by-the-book executions of the three-act structure there is. In fact, if I was going to recommend a template for the execution of the single protagonist comedy, I would put Liar Liar first and Happy Gilmore second. As shocking as it sounds, this screenplay is a thing of beauty.

As many of you know, Happy Gilmore is about a lousy hockey player with anger management issues who’s forced to become a professional golfer in order to save his grandmother’s house. Happy’s unique talent is his ability to drive the ball further than any professional golfer in the world. But after his success begins to draw the ire of tour hot shot and universal asshole Shooter McGavin, Happy finds himself not only struggling to win back his grandmother’s home, but trying to defeat the best golfer in the world.

What I love about Happy Gilmore is that it follows all the rules, yet still manages to feel fresh and funny. It starts by giving us a hero with a flaw. Happy has anger issues. This flaw, while admittedly simplistic, gives our character some depth, something to overcome during the course of his journey. And even better, in “proper” screenwriting fashion, we find out about this flaw not because our hero or some other character *tells* us he has anger issues. We find out through his *actions*. After not making the hockey team, Happy proceeds to beat the shit out of his coach.

This is followed by the inciting incident, the moment in the screenplay that incites a call to action. Happy’s grandmother loses her house because she didn’t pay her taxes. She owes $250,000 dollars and if she doesn’t come up with it within 90 days, the house will be sold off. So our character goal is set: Get $275,000 before the 90 days is up.

In order to beef up that goal, the writers make sure you know that the grandma is the nicest sweetest coolest most loving woman in the world. And because you love her, you want to see Happy get her house back for her. Also, remember how the other day I was talking about positive and negative stakes? How you want your character to not only GAIN something if he wins, but LOSE something if he loses? We have that here when we find out Grandma is staying at the nursing home equivalent of a concentration camp. If Happy gets the money, he gets her house back. If he loses, she’s stuck in this hellhole forever!

But here’s where the genius really kicks in. For most movies to work, your hero must DESPERATELY WANT TO ACHIEVE HIS GOAL. If your hero doesn’t want to achieve his goal, then what’s the point in watching? He doesn’t really care. So why should we? But if someone’s desperately going after a goal doing something they enjoy, where’s the fun in that? Especially in a comedy. It’s much more fun if they DON’T like what they’re doing. And Happy hates playing golf. So then how do you make someone despereately want to achieve something if they don’t like what they’re doing? Simple. You force them into it. So Happy hates golf, but he HAS to play it. And this conflict he has with the sport is what leads to the majority of the comedy in the movie. Again, CONFLICT BREEDS COMEDY. This is how we get Happy swearing up a storm as he tears up a pack of clubs on national TV while the Tour President tries to calm down the sponsors. Or how we get the classic comedy moment of Happy fighting Bob Barker. It’s the key component to the movie working, that Happy wants desperately to achieve his goal, but still hates what he’s doing.

One commonality we see between Happy Gilmore and Dumb and Dumber is that the writers work really hard to make sure you love the main character. We start out with Happy’s voice over. Voice overs always get you into the head of your hero, breaking that fourth wall and making you feel like you know them. So it’s a great device to create sympathy (though still dangerous!). Through it, we find out that Happy lost his father when he was young (sympathy). Happy doesn’t make the hockey team (more sympathy). Happy gets dumped by his girlfriend (more sympathy). Happy employs a homeless man as his caddy (more sympathy). But what you may not have picked up on, is that there’s a very subtle twist to all of these sympathetic moments to draw our attention away from the fact that the writers are pining for our sympathy. Each moment is cloaked inside comedy. In other words, because we’re laughing, we forget that the writers are blatantly manipulating us. When Happy gets kicked off the team, he hilariously beats the shit out of the coach. When his girlfriend leaves him, he screams at her through the intercom (she eventually leaves and Happy is talking to a young boy and an aging Chinese maid). It’s very cleverly disguised inside comedy, and a neat trick to use in your own comedies.

Another great touch is that Happy Gilmore constructs the perfect villain: Shooter McGavin. A lot of writers think you just throw an asshole into the mix and that’ll be enough. Crafting a villain, even in a simple comedy, requires a lot of work. You have to give us someone we hate, but not in that obvious cliché stereotyped way. The mix here of arrogance, passive-aggressiveness, fakeness, and elitism, along with all those annoying little traits (his little “shooting of the guns” and recycled jokes) makes Shooter just a little bit different from the other villains you’ve seen in comedies.

Even the love interest is perfectly executed here. Usually, the love interest in a non-romantic comedy is unnaturally wedged into the story to appease producers. Here, it feels organic to the story. The romantic lead (who’s Claire from Modern Family btw) is the public relations director of the tour. So when one of the tour players is acting up (in this case, Happy Gilmore), it’s only natural that she be brought in to keep him in check. This stuff sounds like it just happens. But you gotta be on your game to make it feel natural. And you have to admit, you never question it in Happy Gilmore.

Chubbs (the one-armed golf pro) is also organically integrated into the script. Whenever you write a sports comedy, you want to not only have an internal flaw (anger, in this case) that the hero battles, but an external one as well, so there’s something physical they have to fix in order to achieve their goal. Here, it’s Happy’s putting. That’s what’s preventing him from beating Shooter. This is the reason Chubbs becomes essential. He has to teach Happy how to putt. Again, it seems obvious, but that’s because it’s so well done.

Another key that makes Happy Gilmore work – and a requirement for any good comedy – is that it exploits its premise. Whenever you come up with a comedy idea, you want to make sure you have 3 or 4 scenes that showcase that idea. That’s why the Bob Barker fight is genius. That’s why Chubbs taking Happy to the miniature golf course and Happy getting in a fight with the laughing clown is genius. These are the moments that represent the audience’s expectations of the idea. If you’re not including these scenes, you might as well not write the movie.

Happy Gilmore is also an incredibly tight script. That was another reason Dumb and Dumber threw me for a loop. It’s over 2 hours long. Most comedies need to be short. You’re making people laugh. Not giving them a history lesson. So by making Happy Gilmore a lean 93 minutes long, it forces the writer to make every scene count. And indeed, every single scene here pushes the story forward. Even the most questionable story-related scene, the pro-am tournament with Bob Barker, sets up Shooter’s goon/cronie who later tries to take down Happy in the Tour Championships.

This is by far the best sports comedy ever made. And just as a straight comedy, it’s pretty high up there as well. If you’re writing a comedy with a single protagonist trying to obtain a goal (like most comedies), you definitely want to study the structure of Happy Gilmore. It’s pretty much perfect.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[x] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Look to make your villain unique through a combination of traits. Shooter McGavin is clever (sending Happy to the 9th tee at nine), passive aggressive (offering backhanded compliments whenever asked about Happy’s talent), cowardly (backing away from a fight) phony (pretending to care about his fans when all he cares about is himself). This combination of qualities gives him a depth that you don’t often see in comedic villains. Making your villain a straight-forward asshole may get the job done, but layering him with numerous quirks and traits will separate him from all the cliché villains of the past.

Genre: Horror

Premise: A group of paranormal researchers move in to the most haunted mansion in the world to try and prove the existence of ghosts.

About: One of our longtime commenters has thrown his hat into the ring. Very excited to finally be reviewing Andrew Mullen’s script! — Every Friday, I review a script from the readers of the site. If you’re interested in submitting your script for an Amateur Review, send it in PDF form, along with your title, genre, logline, and why I should read your script to Carsonreeves3@gmail.com. Keep in mind your script will be posted.

Writer: Andrew Mullen

Details: 146 pages (This is an early draft of the script. The situations, characters, and plot may change significantly by the time the film is released. This is not a definitive statement about the project, but rather an analysis of this unique draft as it pertains to the craft of screenwriting).

Andrew’s been commenting on Scriptshadow forever and I like to reward people who actively participate on the site, so I was more than happy to choose his script for this week’s Amateur Friday. Seeing that Andrew had always made astute points and solid observations, I was hoping for a three-for-three “worth the read” trifecta over the last three Amateur Fridays. What once seemed impossible was shaping up to be possible.

And then I saw the page count.

Pop quiz. What’s the first thing a reader looks at when he opens a screenplay? The title? No. The writer’s name? No. That little box on the top left corner of the PDF document that tells you how many pages it is? Ding ding ding! I saw “146” and my eyes closed. In an instant, all of the energy I had to read Shadows was drained. I know Andrew reads the site so I know he’s heard me say it a hundred times: Keep your script under 110 pages. Of all the rules you want to follow, this is somewhere near the top. And it has nothing to do with whether it’s possible to tell a good story over 110 pages. It has to do with the fact that 99.9% of producers, agents, and managers will close your script within 3 seconds of opening it after seeing that number. They will assume, rightly in 99.9% of the cases, that you don’t know what you’re doing yet, and move on to the next script.

Which is exactly what I planned to do. I mean, I have a few hundred amateur scripts that don’t break the 100 page barrier. I would be saving 45 minutes of my night to do something fun and enjoyable if I went back to the slush pile. But then I stopped. I thought, a) I like Andrew. b) This could serve as an example to amateur writers WHY it’s a terrible idea to write a 146 page script. And c) Maybe, just maybe, this will be that .01% of 146 page screenplays that’s good and force me to reevaluate how I approach the large page count rule.

So, was Shadows in that .01%?

Professor Malcom Dobbs and Dr. Butch Rubenstein are founders of the premiere paranormal research team on the planet. They’re the “Jodie Foster in Contact’s” of the paranormal world, willing to go to the ends of the earth to prove that ghosts do, in fact, exist. And they’re currently residing in the best possible place to prove this – a huge mansion with sprawling grounds known as Carrion Manor – a house many consider to be the most haunted in the world.

But with their grant running out, so is their time to prove the existence of ghosts, so the group is forced to take drastic measures. They head to a local nut house and ask for the services of 20-something Brenna, a pretty and kind woman with a dark past. Her entire family was slaughtered when she was a child, and that night she claimed to have heard voices, whispers, contact from another realm. This “contact” is exactly what our team needs to ramp up their experiments.

Basically, what these guys do is similar to the “night vision” sequence in the great horror film, “The Orphanage,” where they use all their technical equipment like computers, and cameras, and microphones, to monitor levels of energy as Brenna walks from room to room throughout the manor. This is one of the first problems I had with the script. There isn’t a lot of variety to these scenes. And we get a lot of them. Brenna walks into a room. The levels spike. Our paranormal team is excited. Some downtime. Then we repeat the process again.

During Brenna’s stay, she starts to fall for one of the team members, a child genius (now 27 years old) named Dr. Schordinger Pike. This was another issue I had with the script, as the development of Pike and Brenna’s relationship was way too simplistic, almost like two 6th graders falling in love, as opposed to a pair of 27 year olds (“She’s way out of my league. Right? Right. Not even the same sport!” Pike starts hyperventilating). Also, I find that when the love story isn’t the centerpiece of the film (in this case, the movie is about a haunted mansion) you can’t give it too much time. You can’t stop your screenplay to show the two lovers running through daisies and professing their love for one another. You almost have to build their relationship up in the background. Empire Strikes Back is a great example of this. Han and Leia fall in love amongst a zillion other things going on. Whereas here, we stop the story time and time again to give these two a scene where they can sit around and talk to each other. Always move your story along first. Never stop it for anything.

Anyway, another subplot that develops is the computer system that’s monitoring the house, dubbed “Casper.” Casper is the “Hal” of the family, and when things start going bad (real ghosts start appearing), Casper wants to do things his way. You probably know what I’m going to say here. A computer that controls the house is a different movie. It has nothing to do with what these guys are doing and therefore only serves to distract from the story. You want to get rid of this and focus specifically on the researchers’ goal (trying to prove that there are ghosts) and the obstacles they run into which make achieving that goal difficult.

I will say there’s some pretty cool stuff about the eclectic group of former house owners, and the fact that a lot of them had unfinished business when they died clues us in that we’ll be seeing them again. And we do. The final act is 30 intense pages of paranormal battles with numerous ghosts and creatures coming to take down our inhabitants, some of whom fall victim to the madness, some of whom escape. But there are too many dead spots in the script, which makes getting to that climax a chore.

So, the first thing that needs to be addressed is, “Why is this script so long?” I mean, did we really need this many pages to tell the story? The simple and final answer is no. We don’t need nearly this many pages. The reason a lot of scripts are too long is usually because a writer doesn’t know the specific story they’re trying to tell, so they tell several stories instead. And more stories equals more pages. This would fall in line with my previous observation, that we have the needless “Casper” subplot and a love story that requires the main story to stop every time it’s featured.

Figure out what your story is about and then ONLY GIVE US THE SCENES THAT PUSH THAT PARTICULAR STORY FORWARD. Doesn’t mean you can’t have subplots. Doesn’t mean you can’t have a minor tangent or two. But 98% of your script should be working to push that main throughline forward. So if you look at a similar film – The Orphanage – That’s a film about a woman who loses her son and tries to find him. Go rent that movie now. You’ll see that every single scene serves to push that story forward (find my son). We don’t deviate from that plan.

Another problem here is the long passages where nothing dramatic happens. There’s a tour of the house that begins on page 59 that just stops the story cold. We start with a couple of flirty scenes between Brenna and Pike as we explore a few of the rooms. Then we go into multiple flashbacks of the previous tenants in great detail, one after another. After this, Pike offers us a flashback of his OWN history. So we had this big long exposition scene regarding the house. And we’re following that with another exposition scene. Then Pike shows Brenna the house garden, another key area of the house, and more exposition. This is followed by another character talking about a Vietcong story whose purpose remains unclear to me. The problem here, besides the dozen straight pages of exposition, is that there’s nothing dramatic happening. No mystery, no problem, no twist, nothing at stake, nothing pushing the story forward. It’s just people talking for 12 minutes. And that’s the kind of stuff that will kill a script.

Likewise, there are other elements in Shadows that aren’t needed. For example, there’s a character named Lewis, a slacker intern who never does any work, who disappears for 50-60 pages at a time before popping back up again. We never know who the guy is or why he’s in the story. Later it’s discovered he’s using remote portions of the house to grow pot in. I’m all for adding humor to your story, but the humor should stem from the situation. This is something you’d put in Harold and Kumar Go To Siberia, not a haunted house movie. Again, this is the kind of stuff that adds pages to your screenplay and for no reason. Know what your story is and stay focused on that story. Don’t go exploring every little whim that pops into your head – like pot-growing interns.

This leads us to the ultimate question: What *is* the story in Shadows? Well, it’s almost clear. But it needs to be more clear. Because the clearer it is to you, the easier it will be to tell your story. These guys are looking for proof of the paranormal. I get that. But why? What do they gain by achieving this goal? A vague satisfaction for proving there are ghosts? Audiences tend to want something more concrete. So in The Orphanage, the goal is to find the son (concrete). In the recently reviewed Red Lights, a similar story about the paranormal, the goal is to bring down Silver (concrete). If there was something more specific lost in this house. Or something specific that happened in this house, then you’d have that concrete goal. Maybe they’re trying to prove a murder or find a clue to some buried treasure on the property? Giving your characters something specific to do is going to give the story a lot more juice.

Here’s the thing. There’s a story in here. Paranormal guys researching ghosts in the most haunted house in the world? I can get on board with that. And there’s actually some pretty cool ideas here. Like the old knight who used to live on the property who was never found. There’s potential there. But this whole story needs to be streamlined. I mean you need to book this guy on The Biggest Loser until he’s down to a slim and healthy 110 pages. Because people aren’t going to give you an opportunity until you show them that you respect their time. I realize this is some tough love critiquing going on here, but that’s only because I want Andrew to kick ass on the rewrite and on all his future scripts. And he will if he avoids these mistakes. Good luck Andrew. Hope these observations helped. :)

Script link: Shadows

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: This script was a little too prose-heavy, another factor contributing to the high page count. You definitely want to paint a picture when you write but not at the expense of keeping the eyes moving. Lines like this, “A dying jack o’ lantern smiles lewdly. The faintly glowing grimace flickers in the dark as if struggling for life,” can easily become “A flickering jack o’ lantern smiles lewdly,” which conveys the exact same image in half the words. Just keep it moving.

Genre: Comedy

Premise: Three men on the verge of middle age celebrate a bachelor party at Glastonbury, a notorious mythic music festival in the UK.

About: (Correction – Although Sean does have credits, he does not have representation). — If you are a repped or unrepped writer, feel free to submit your script for Amateur/Repped Friday by sending it (in PDF form) to Carsonreeves3@gmail.com. Please include your title, genre, logline, and why I should read your script. Also keep in mind that your script will be posted.

Writer: Sean Vaardal

Details: 103 pages – Feb. 14, 2011 draft

Lots of people have asked me to write an article on what makes a great query letter. That article has been written somewhere in the neighborhood of 713,000 times already, so I’m not going to rehash it here on Scriptshadow. But I will broach the subject because Sean’s query to me is the reason I picked him for today’s review. Before I get to Sean, let me address a few general thoughts.

Guys, I love you. And you send me some really passionate stories about how difficult it is out there and how hard it is to get your work noticed. However…I can’t pick your script when every tenth word in your query letter is misspelled. i can’t pick ur script if u don’t capitalize or punctuate correctly or if you write 2 me in text speak. I can’t pick your script if you ramble on incoherently about your concept or your aspirations. If you ramble on in a 500 word query letter, I can only imagine how unfocused your screenplay is going to be.

You need to approach your query letter with the same level of professionalism you’d imagine Ernest Hemingway would have done it. That’s not to say you should be buttoned up and humorless. But be focused, devoid of mistakes, and get to the point quickly. I thought Sean’s query was pretty much perfect, so I decided to include it here. Here’s what he wrote…

Dear Carson,

I am a scriptwriter with credits on two award-winning British comedy shows Smack The Pony and Monkey Dust.

I would like to send you my new feature-length script, a comedy called Glastonburied.

I got the idea after an article in The Economist, which said 43 is the age at which you are apparently no longer young. According to this, I have only 6 months left before I am ‘officially’ old. But what I want to know is: How do you stop being young, and are you supposed to? And if so, when does the wisdom start kicking in?

I thought this ‘tipping point’ idea was a good way of analysing three, 40-something friends over a weekend at the Glastonbury music festival. A place where people go to lose themselves or find themselves. A place where all your dreams can come true, a place of myths and legends, bands and chaos, where you might enter an innocent but leave with a rare, new kind of knowledge.

Glastonburied is like The Breakfast Club for adults. It combines male identity themes reminiscent in Sideways, with the added mayhem of Withnail & I.

Go on Carson, you old mucker, make it your Amateur Friday pick of the month.

Cheers,

Sean

Now I don’t know what a “mucker” is, and I’m not going to speak for every agent, manager, and producer out there, but I’ll tell you why this worked for me. First, he exhibits a clear grasp of the English language, which indicates to me that at the very least, his writing will be easy to read. Next, he uses a well-known trick to pitch his idea – relating his screenplay to his own life. If I believe that there are some personal issues you’re exploring in your script, I know I’m reading something meaningful to the writer, which almost always ends up in a better screenplay. Sean also gives me a couple of movie references so I know what to expect, and ends with a pleasant-humored challenge, encouraging me to give his script a shot.

Now, of course, this query got me to read the screenplay. But that doesn’t mean I’m going to like it. Did I like Glastonburied? Read on to find out.

Gary Newman is a piano bar singer just north of 40 who’s beginning to have panic attacks during his performances. It seems as if Gary’s directionless life has finally caught up with him, a life that was once quite promising . You see, back in 2003, Gary won one of those “Idol” shows in Britain, and was for a brief time on top of the world. Clearly, that top has bottomed out.

Adding salt to the wound, Gary’s fiance just called off their wedding. The reason being simply… he’s a shell of his former self. It would’ve been nice, of course, if she would’ve told him this BEFORE Gary’s two best friends showed up for his weekend bachelor party. And because Gary doesn’t want to deal with the consequences of telling them what happened, he decides to keep the break-up a secret.

The friends in question are Jeff, a once moderately successful actor, not unlike Thomas Hayden Church in Sideways, and Keith, a rich family man desperately clinging to his youth. The three of them head off to Glastonbury, a famous/infamous music festival where people go to lose themselves, in search of one last wild time together before Gary gets married (or not).

Naturally, once they get to the festival, all hell breaks loose. A urinating witch immediately puts a spell on them, they befriend a couple of hot young ladies who may be Nazi sympathizers, they meet and participate in some local cult rituals, and of course do a lot of drugs. The characters in Glastonburied do a LOT of drugs. In the end, Gary must decide whether to embrace the next stage of his life or stay trapped in his middling existence forever.

Alright so, first off, let me just say, Sean, I’m on your side. I liked the presentation. I liked the pitch. But since it does nobody any good if I sugar coat my reaction, I’m going to hold Glastonburied to the same high standards I hold million dollar sales. I think this script needs a considerable amount of work. And it starts with the main character. I have a tough time accepting lead characters as celebrities or former celebrities in a character piece, because there’s nothing relateable to an audience about someone who’s a current or former celebrity. Think about it. How many people have won an American Idol like competition in their life? 200? 250? So that’s 250 people who know exactly what your main character feels like. There are obviously exceptions and there was a connection between the character’s past (he’s a musician) and the current situation (he’s at a music festival), but here’s the specific reason why it didn’t work for me: It was false advertising. In the query letter, it was implied I would read a personal everyman journey. That’s the whole reason I wanted to read it! Because it was tackling a normal everyday guy’s collision with that most relate-able of relate-able situations: getting older. So when the main character was given this totally specific celebrity past, every drop of realism, every ounce of that “everyman” I was hoping for, instantly vaporized.

I was also bummed about the way the story was set up. What hooked me in the query was the bit about a guy learning he had six months before officially becoming “old,” and therefore wanting to do something exciting with his last bit of “youth.” But in the script, this line (about becoming 43) is buried deep within the second act, long after it’s lost its significance. That line was the perfect inciting incident for the movie and the fact that it has nothing to do with why he and his friends go to Glastonbury was a bummer.

The structure here needs work as well. Glastonburied is missing three very important story elements: A character goal, stakes, and urgency. Gary isn’t trying to obtain any goal in the script other than a vague sense of holding onto his youth. And since he’s not trying to obtain any goal, there are no stakes to his journey. You can’t gain or lose anything if you’re not going after anything in the first place. And of course, since there’s no goal or stakes, there’s no urgency. You can’t be in a hurry to achieve anything if there’s nothing you’re trying to achieve.

This leaves the plot in the same hole so many other struggling comedies find themselves in: it’s essentially a loosely connected series of comedic situations. This is great if you’re directing a Saturday Night Live episode, but not if you’re constructing a story where all the pieces are supposed to fit together.

Let’s go back to Hangover to see how this is executed. Notice how CLEAR these three elements are.

Goal: Find Doug.

Stakes: If they don’t find him, he doesn’t get married.

Urgency: They have two days before the wedding.

I’m not saying to copy this exact structure by any means, but these elements need to be in place for a comedy such as this to work. You also need to be aware of when specific story choices eliminate these opportunities. For example, Gary’s wife breaking up with him before the bachelor party was an interesting choice, but in making that choice, the ticking time bomb (urgency) was eliminated. There’s no need to get to the wedding if the wedding doesn’t exist.

I think a lot of my reaction goes back to the fact that I felt misled from the query. If this was going to be a goofy romp with lots of drugs and pissing witches and strange cults and that sort of thing, that’s fine. That type of comedy can work. But if I’m going in believing this is another Sideways or Breakfast Club

, I’m going to be sorely disappointed. That’s a big lesson I learned here. Don’t falsely sell your script in your query. Make sure it’s representative of what you’ve pitched. But hey, maybe I’m being way too hard on Sean here, and since you guys will be going in with a better understanding of what the script’s about, you very well might love it. A comedy set at one of these crazy ass music festivals is a good idea. Download it yourself and leave your thoughts in the comments section.

Script link: Glastonburied

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Whatever genre you’re writing, make sure the tone of your query reflects that genre. So if it’s a comedy, throw a joke in the e-mail to prove that you’re funny. If it’s a dark drama, keep the query more professional and straight-forward. Whatever the case, please, before you send your query to anyone, give it to your parents or the most anal punctuation/spelling Nazi you know and ask them to weed out all of the mistakes. It’s hard to catch the eye of someone in this industry. They’re all so busy. So bring your best game to that query.