Today’s review isn’t so much about Jurassic World as it is about changing your life.

Genre: Action-Adventure

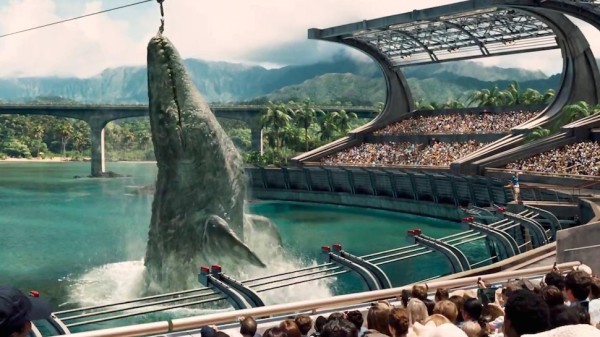

Premise: In order to draw in more customers, a dinosaur theme park genetically modifies a T-Rex to make it bigger, badder, and scarier. Yeah, like that’s going to turn out well.

About: Universal’s been desperate to make another Jurassic Park film for years. The problem was always, “Why would an audience want another Jurassic Park movie?” The last one was terrible. And there are only so many ways to go back to that park. But Universal stayed the course, believing in their product, and boy did it pay off this weekend. The movie made 205 million dollars. Some say it even saved the summer movie season, as the box office numbers this summer have been dismal. One of the biggest gambles for Universal was the hiring of director Colin Trevorrow, a director with only one feature credit to his name, the well-received but microscopic indie film, “Safety Not Guaranteed.” Spielberg himself signed off on Trevorrow.

Writers: Rick Jaffa & Amanda Silver and Colin Trevorrow & Derek Connolly (story by Rick Jaffa & Amanda Silver – some characters by Michael Crichton)

Details: 124 minutes

If you had told me four months ago that Jurassic World was going to gross 200 million dollars on its opening weekend and have the largest global opening of all time (north of 500 million), I would’ve said, “Yeah, and I’m a stegosaurus.”

Yet, improbably, the franchise many thought was out of pterodactyl juice, has positioned itself to be the number 1 grossing film of the year. That’s in a year that has The Avengers 2 and Star Wars 7! We’re still a ways away from that announcement, but however the raptor claws choose to slice it, it’s gotta be considered the biggest surprise of the year. I guess people still really like dinosaurs!

The plot for Jurassic World is pretty much this: Genetically-spliced killer dinosaur gets loose on an island. It starts killing everything.

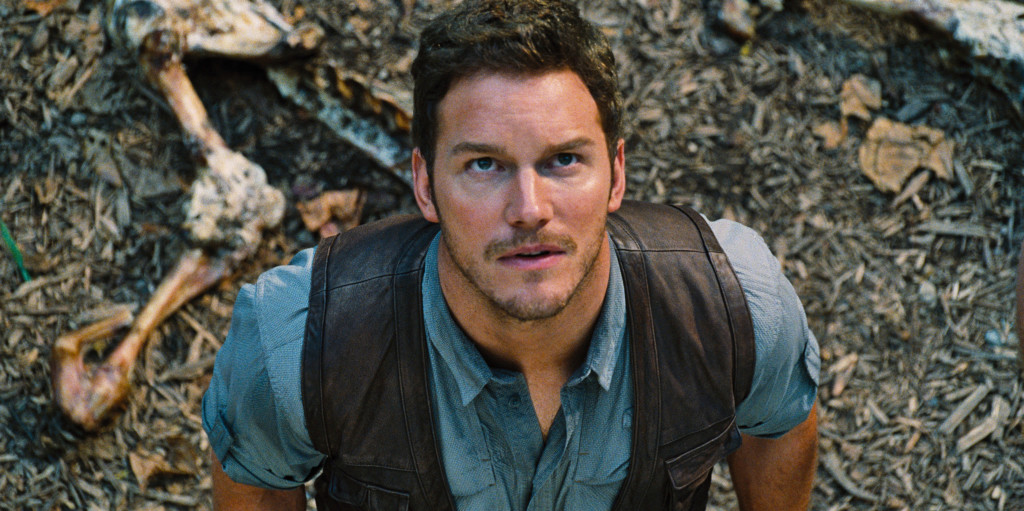

This dinosaur’s potential appetizers include Owen, a rough-and-tumble grease-monkey who’s been training raptors to obey human commands. There’s brothers Zach and Gray, both struggling with the impending divorce of their parents. And then there’s Claire, the uptight manager of Jurassic World who, as Zach and Gray’s aunt, has been charged with taking care of them for the weekend.

Claire is really the centerpiece of the movie, as these two poles (Owen on one side and Zach and Gray on the other) try to warm the ice queen up. If you really break it down, Jurassic World is about how life doesn’t always go as planned and the importance of learning to accept that and adapt to it.

And dinosaurs killing each other of course.

I’m sure you’d like to hear what I thought of Jurassic World but, to be honest, you could look at 20 other reviews online and get a close approximation of how I felt. This is a big dumb movie meant to be enjoyed with the lights turned off. Both in the theater and in your heads. It’s not groundbreaking but it’s better than you expect it to be, nudging itself into the “second best” position of the four Jurassic Park films. Which means Trevorrow outdid one of Spielberg’s entries. Not bad for someone who’s never made a blockbuster before.

So all that’s fine and dandy. But there’s a much bigger story here for those paying attention. And it’s a story that could change your lives. A guy wrote and directed a dirt-cheap indie film with one special effects scene and was handed the reins to a major studio franchise. I want you to think about that for a second. I mean really think about it.

Tomorrow, you could start developing a feature film. In five months, you could be shooting it. In a year, you could be in Steven Spielberg’s office discussing the success of that film and be offered a major franchise. Sound impossible? We JUST saw it done. And now that it’s BEEN done, you can bet your ass that studios are going to give chances to MORE up-and-coming directors with only one small film on their resume.

I mean, have you heard some of the names being considered for the next Spider-Man film? The director of Napolean Dynamite. The director of Me, Earl, and the Dying Girl. This is happening. The ride has started. Get on it!

But why is it happening? Well, here’s how I see it. The special effects industry has things figured out on their end. So studios feel confident they have that covered. They know the computer wizards are going to give them those “wowee” shots they can highlight in a trailer to bring audiences in.

What the studios don’t have covered is good storytellers, people who understand how to build a story, how to create suspense, but most importantly, how to arc characters.

Movies, at their core, represent our connections with people. We must connect in some way with the souls who are taking us on this journey. And during that journey, those souls must learn something through the experience they’re put through. They must come out on the other side better people in some way, giving hope to the human experience – that we are capable of becoming better versions of ourselves.

It sounds like screenwriting book bullshit but I would say the ability to show character change in a convincing and emotionally compelling way is what separates the men from the boys. Because anyone can write an action scene. Anyone can scribble, “And then the T-Rex crushes the copter in half with its jaws.”

But not everyone can take the character of Claire, establish her inability to connect in any emotional capacity, and then use the story to challenge that flaw until, in the end, she figures out how to open up. It’s just not done in the vast majority of amateur screenplays I read. And, often times, it’s the reason one’s story leaves so little emotional impact. If everyone in the story is the same at the end as they were at the beginning, then what was the point of telling the story in the first place?

But I don’t want to get hung up on negatives. I’m just thrilled to see what was once thought to be impossible opportunities now presenting themselves regularly. The industry is always going to be hard up for great storytellers.

Make your movies. Let them see what they’re missing. Then celebrate when you get that call from Spielberg.

[ ] what the hell did I just watch?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the price of admission

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: If you want to make big sci-fi movies like Jurassic World, write or direct an indie film with some sort of sci-fi storyline. Colin Trevorrow doesn’t get the Jurassic World call if Safety Not Guaranteed is about a horrible-with-women CEO who falls in love with a Speed Dating coach. His movie was about a guy who claims he’s going to travel back in time. This might seem obvious but I see a lot of writers writing in genres that have nothing to do with the genre they eventually want to make big movies in. So just be smart about that.

I hope nobody’s experiencing any lasting psychological effects from Weird Scripts Week. I know I’ve been unaffected by it. The pet monkey I purchased yesterday has been working out splendidly. Still learning how to deal with the beating of the chest and the feces throwing. But other than that, I think this was a wonderful decision. Still trying to figure out how I came up with the idea. You guys have 47 days left til the Scriptshadow 250 Screenwriting Contest deadline, so keep writing. In the meantime, here are five juicy distractions.

Title: Triumph and Disaster

Genre: Dark Comedy

Logline: A man with frontal lobe damage teams up with a sex addicted widow and a porn-obsessed autistic teenager to race to Las Vegas to meet Lynda Carter, aka Wonder Woman, in an attempt to get the man’s restraining order lifted — all while their respective loved ones do everything they can to stop them.

Why you should read: I know there’s been some opposition to scribes getting reviewed more than once, but my script NERVE AND SINEW got a ‘worth the read’ last year, and I think this one is at that level (or even hopefully beyond it). It’s a low budget, simple story with memorable, complex characters. And sex. A pretty good amount of it. Also, this script takes the opportunity to honor Lynda Carter before she gives way to Gal Gadot.

Title: A Harry Dick Apocalypse

Genre: Horror-Comedy

Logline: A cynical poker player who must become America’s ace in the hole when he bluffs his way into the president’s secret bunker during a global cataclysm.

Why you should read: I’ve been writing for much of my adult life but exclusively screenplays for the past eleven years. One of the best compliments I’ve received about the script is that the reader didn’t have to read the character slug-lines to know who was speaking. The best compliment I’ve had is that it’s a funny story. My inspiration was “Dawn of the Dead” (I know you hate zombies but they are just garnish on the plate) and “Dr. Strangelove,” with a dash of Woody Allen’s “Banana’s.” I tried to make the characters as neurotic as those on the TV series, “The Office.”

Random Submission E-mail found in Carson’s Inbox:

HI, there,

I understand from the web that you are looking to have a movie script reviewed.

Please feel free to Google me (Ab Vegvarry) and if you are still interested get in touch, and you won’t be disappointed.

regards,

Abb Vegvary

(no script attached)

Title: Chickin Lickin

Genre: Drama/Coming of Age

Logline: A tentative young woman gains confidence after the rescue of a baby chicken brings her under the tutelage of a Miyagi-style mentor who trains roosters for cock-fighting.

Why you should read: Cock-fighting is outlawed in the continental U.S. but still legal in Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands. I’ve been living in St. Thomas for the past 20 years and wanted to utilize an unusual dynamic which might feasibly only exist there, in order to write a different sort of coming of age story. Hope it works! Thanks for checking it out.

Title: Every Good Intention

Genre: Drama/Thriller

Logline: In the wake of their mother’s death, estranged brothers Darren and Reed Holt find themselves at odds with one another after “the perfect robbery” goes horribly wrong, threatening both of their lives.

Why you should read: EVERY GOOD INTENTION is set among the backdrop of Cleveland, Ohio, where the lifestyles of its citizens can be as harsh as the ever-changing seasons. If you love a great character-driven story, you will appreciate this tale of complicated relationships, wasted pasts and foolish pride. If you prefer the intensity of an action-driven script, then you will certainly enjoy the dramatic consequences and fallout that arise from a robbery gone awry. To sum it all up, think OUT OF THE FURNACE meets A SIMPLE PLAN. This is a script that reads like a 90 minute gritty Bruce Springsteen ballad. I realize it can be a challenge to pull off a satisfying character story these days that lacks all the CGI and big-budget effects, however, sometimes real life can be pretty interesting. I wanted to write a story that someone could read and say, “I know a guy like this, and could see that happening…”

Title: Death of the Party

Genre: Thriller/Slasher

Logline: A privileged teen is terrorized by a Snapchat serial killer, while her party guests fall prey at her secluded mansion.

Why you should read: When writing this script, our main goals were to always keep the reader guessing, always keep the reader entertained, and to write a movie we would want to see on opening night. — DOTP is lean. It’s fast-paced. It’s a suspenseful, genre-bending tale, written to maximize mystery, tension, and fear. But most importantly, it’s FUN! — We are graduates of The Second City Chicago (commonly referred to as the Harvard of Comedy). Although this isn’t a comedic script, SC gave us the tools to know how to concoct a story that gets to the point quickly, has no fat, and packs a wallop. In sketch format, there’s no time for unnecessary frills. You have to hook them quickly, and keep them riveted, or die a horrible, horrible death in front of an unforgiving crowd that’s not afraid to boo you right off the Windy City stage.

Is today’s script a spiritual sequel to yesterday’s entry? They’re both about bubbles. As long as we’re on the topic, David Lynch should ditch Saliva Bubble and direct this. It would be EPIC!

It’s finally here! The culmination of Weird Scripts Week! On Monday you saw us deal with James Bond and robot sharks. On Tuesday, talking cows. On Wednesday we went into the mind of a man living his own musical. Yesterday’s script was about spit. But today is truly the pinnacle of weirdness. Get the drugs out and enjoy…

Genre: Biopic

Premise: I told you I was saving the craziest for last. How ‘bout a biopic of Michael Jackson told through the eyes of his chimpanzee, Bubbles!

About: This script went out earlier this year, and while it’s got about as much chance of getting made as Uwe Boll does helming a Star Wars movie, it wins the “Oh I’ve gotta read this” premise of the year award. While writer Isaac Adamson doesn’t have a legendary list of IMDB credits, he’s far from a stranger to Hollywood. His first novel, Tokyo Suckerpunch, has been in development for years at Sony. If Allan Loeb’s Collateral Beauty is ending up number 1 on this year’s Black List like everyone is telling me it will (I still haven’t read it – saving it for when I can relax and enjoy), my guess is that Bubbles ends up at number 2.

Writer: Isaac Adamson

Details: 122 pages

Isaac Adamson, I don’t know who you are. But you’re a genius, my friend.

This is one of those ideas you and your screenwriting friends come up with at 3 in the morning after a night of drinking, laugh uproariously about, then after the laughter’s died down, you proclaim, “No, but really, what if I ACTUALLY wrote it?” And then everyone laughs and says, “Yeah, you should TOTALLY write it.” “Oh my God. Yeah. That would be hilarious!”

And then the next morning through the foggy haze, before you’ve emptied your loose change on three Sausage McGriddles, you remember your crazy premise about telling Michael Jackson’s story through his chimpanzee’s point of view and you grimace and say, “Was I bananas??”

Isaac Adamson must have put down the McGriddles because he not only wrote it, he committed to it. And really, that’s the only way to do it. When you come up with a gimmick premise, you quickly find that there’s nothing to really say past page 15. You’ve introduced the gimmick. What’s left to do?

If you want to extend an idea like that into feature length, you have to embrace and treat the characters like real people, with real problems and real conflicts. And with the exception of Bubbles’ thoughtful meanderings, that’s exactly what Adamson does.

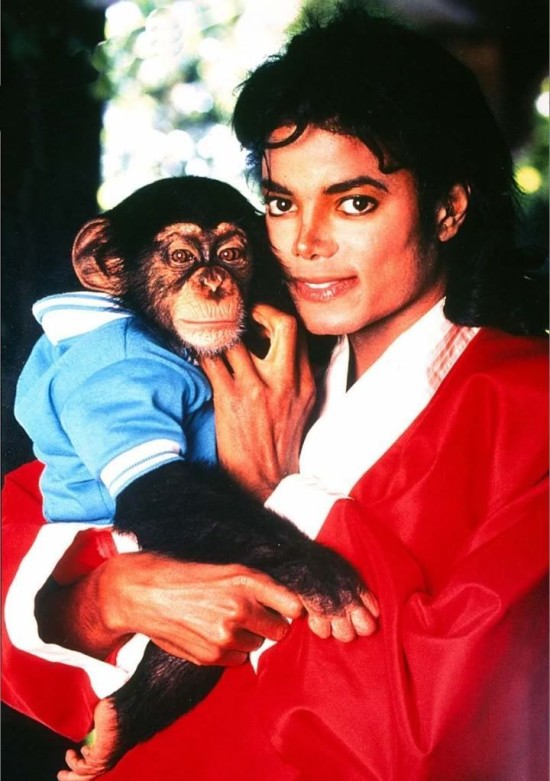

“Bubbles” opens up with a voice over from Bubbles himself. It’s present day and Bubbles lives in a cage along with a number of other animals. He’s not thrilled about it, but as he explains to us in the coming pages, he’s not sure he prefers his previous life either.

Flash back to 1985, the height of Michael Jackson’s fame. Michael has just come out with Thriller, the biggest album of all time! And he wants more. He wants his next album to do the impossible – to sell 100 million records.

He also doesn’t want to be alone during that journey. When you reach that kind of fame, it’s difficult to find friends. This is usually where your family comes in, but Michael’s family, particularly his evil father, Joe, is more interested in using Michael’s fame to jumpstart their own careers than support and love their son/brother.

So Michael buys a monkey! Whereas Michael is childlike and simplistic, Bubbles is a cross between an overly-educated Oxford graduate and a Roman philosopher. He ruminates about Michael’s life choices with such voice over lines as: “Should I have been alarmed that the notion of myself as sovereign provoked such laughter from The King? Or that seeing me festooned in the regal accouterments induced only befuddled discomfiture from these hirsute gentlemen of New Jersey?”

Michael and Bubbles become fast friends, and Bubbles takes pride in that a man who everyone refers to as “The King” has made him his prince. We follow the two through Michael’s struggles to make that impossible 100 million copy album, and during that time, Bubbles, too, becomes a celebrity (particularly in Japan).

But things start to change when Michael moves into Neverland Ranch, a place where he’s finally free of his blood-sucking family. Neverland brings with it many children, distracting Michael from Bubbles. And when one particular child, Jordan Chandler, becomes Michael’s best friend, Bubbles feels like he’s on the outs.

When Jordan’s father (who happens to be a screenwriter!) threatens to sue Michael for molesting his child, Michael’s kingdom, as well as his friendship with Bubbles, unwinds to a point where it can never be salvaged again.

We always talk about how once you find your idea, or your subject, you need to find your angle. Your angle can take what’s, at face value, a generic idea, and bring it to life. I mean, imagine if this was just another Michael Jackson biopic. Adamson would be lucky if Lifetime requested it. By exploring Michael through the angle of his pet chimpanzee, we get a completely unique perspective of the pop star. What was once dull is now fresh. This was the first great choice Adamson made.

The second was to treat everybody here like real people. Once you treat your characters like real people, your reader will actually invest in them. This doesn’t work if you play everyone as a farce. This was my problem with yesterday’s script. Nobody in One Saliva Bubble was real. They were all goofy gimmicks, and therefore we could never get inside of them. For a short movie, gimmicks are fine. For a feature, though? If you’re going to ask someone to sit still for two hours? You need to give them something to invest in.

With that said, I was surprised how far Adamson went down this path. I was curious how he would treat the child molestation charges on Michael but he faces them head on – to the point where they’re the climax of the story (okay, that was unintended, I swear). And because we’d invested so much in Michael by this point – seen how everyone around him existed only to take advantage of him – we really cared about what happened next.

Bubbles the character is a mixed bag. His high-brow observations do get a little tedious at times, but more often than not, they’re fun. For example, when Michael leaves the house only to come back with bandages on his face, Bubbles assumes that his “King” must have gone off to battle, defending his kingdom and defeating his many foes.

And it’s not like he’s unconnected to the plot. His jealousy of the people who hang around Michael are what drive his actions, and it’s why (spoiler), in the end, he’s forced to leave Neverland Ranch.

My issues with “Bubbles” are tempered by the commitment to the idea, but I did have a problem with the script length. This is the kind of premise you want to get in and out of faster than a Hollywood and Vine escort. There’s an entire “Michael in the UK” section that Bubbles doesn’t even participate in that easily could’ve been excised.

I also wished there was more Joe. When you have any script that doesn’t fit nicely into a movie-like structure (which is the case with most biopics), a great villain can be a huge help. You get the audience so wound up about the antagonist and so obsessed with seeing his demise, that they don’t even notice the movie’s flying by. From everything I’ve read, Joe Jackson is a terrible person, especially to Michael. So I would’ve loved to have seen that conflict explored more.

This script will probably never sell and most definitely will never be made. But it does so much more. It shows Hollywood that you’re not afraid to think outside of the box. And while Hollywood loves its formulas, the people who work within it secretly pain for these new voices, for new ideas, for new angles. Those angles may never make it to the big screen, but those writers are admired and called upon again and again for potential writing assignments because they showed that they could go where other writers were too afraid to. So while Bubbles isn’t a perfect story, it’s perfect in its uniqueness, which is why I’d be an idiot not to call it impressive.

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[x] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: As simplistic as this sounds, if there’s one thing I’ve learned from this week, it’s that if you want to write something weird, utilizing animals in some unique way is a good place to start. Especially if you want to make the Black List, which thrives on celebrating weird stories. High-ranking Black List scripts The Beaver, The Muppet Man, and The Voices all focused on animals in some weird way. Add Bubbles to that list.

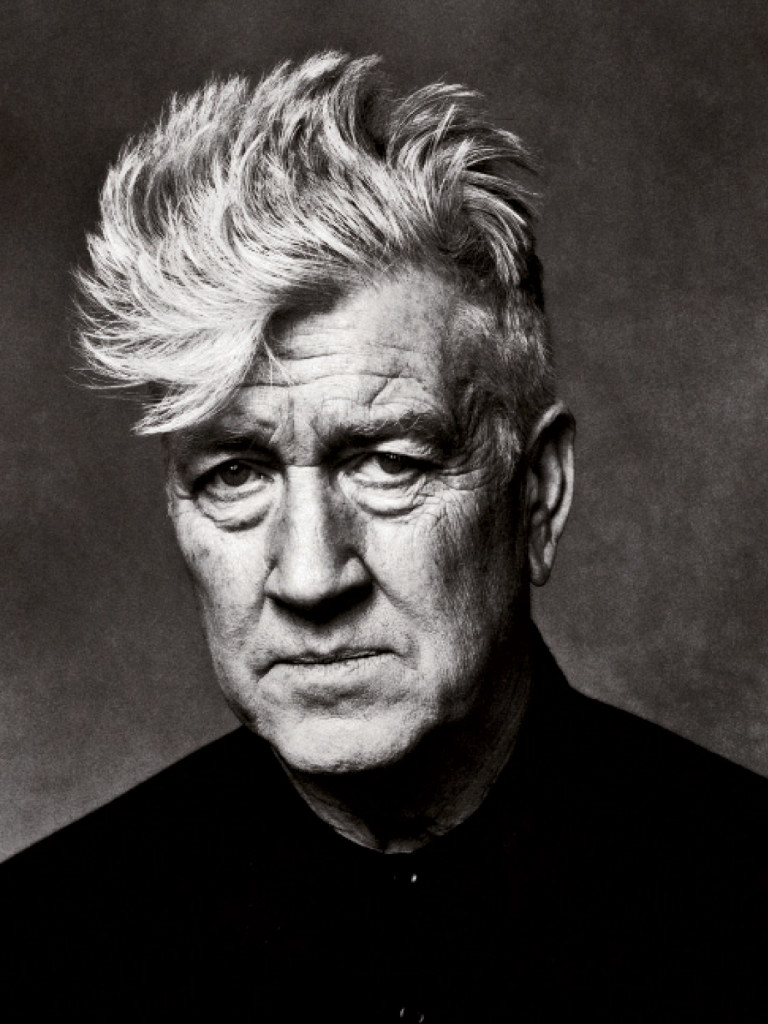

You didn’t think we’d go through an entire Weird Scripts week without reviewing a David Lynch script, did you?

Welcome to Weird Scripts Week! This week, I’ll be reviewing odd scripts, odd ideas, and writing that’s just plain odd. It will all culminate Friday when I review the strangest premise I’ve ever reviewed on Scriptshadow. To check out Monday’s cross between an aquarium and a power drill, click here. Tuesday’s script will turn you into a vegetarian. Yesterday’s script will send you off into your own 24 hour video. And today is… well today we’re talking about spit.

Genre: Comedy?

Premise: When a guard’s tiny saliva bubble shoots out of his mouth and into the circuitry of a top-secret government project, it starts a chain reaction that discombobulates an entire town.

About: After some grandstanding from both Showtime and David Lynch on budget issues for Lynch’s new version of Twin Peaks, the series will be making a return later this year. A couple of low-rated Showtime shows may pay the price for that but if you want to work with visionary directors, there will be casualties. Speaking of casualties, One Saliva Bubble is Lynch’s passion project, and I don’t think he’s ever gotten over having to move on from it. The director of such films as Eraserhead, Dune, and Mulholland Drive actually had a co-writer on this script named Mark Frost, who went on to write the two 2000s Fantastic Four movies. He was also a writer on the original TV version of The Equalizer.

Writers: David Lynch and Mark Frost

Details: 140 pages (first draft – 5/20/87 draft)

For our fourth script in this week’s Weird Scripts series, we’re going to the granddaddy of weird – the maestro of misinterpretation, the grand pooba of pointlessness, the conductor of confusing. Yup, I’m talking about David Lynch. The old school Lynch came up during a time where you were actually encouraged – gasp – to be different. To try new and offbeat things.

What Lynch’s mentors didn’t know was that telling him this was like telling Homer Simpson he could design his own donut line. You talk about a guy who took advice to heart. Sheesh. I’d expect more sense out of an Amanda Bynes and Miley Cyrus collaboration than I do this man’s movies. Does One Saliva Bubble fall in line with the rest of his work? We shall see…

Somewhere near the tiny town of Newtonville is a secret military base. It just so happens that on this evening, at this base, a few guards are joking around near an exposed computer panel, and a spittle of saliva shoots out of one of their mouths, lands on the panel, and short-circuits a tiny portion of the wiring.

This causes a malfunction whereby the panel erroneously sends a signal to a military satellite to start a countdown sequence for some top secret weapon. 24 hours later, this satellite shoots a laser beam down to Newtonville, which bounces around, hitting almost everyone in town.

The hardest hit is the airport. It’s there where our four protagonists are located for various reasons. There’s the psychotic contract killer, Horton Thursby, the genius Swiss scientist, Professor Hugo Zinzermacher, the loser middle-aged family man, Wally Newton, and the town idiot, who’s just come back from the insane asylum, Newt Newton.

What this laser beam does is it displaces the minds of our four characters, so that Horton and Wally switch bodies and Hugo and Newt switch bodies. For reasons I can’t even begin to explain, while their personalities have been transported, none of the characters actually know they’re inside new bodies.

This leads to mayhem. For example, a major company has brought Professor Hugo in from Sweden to help them come up with a winning formula to defeat their nemesis. But instead, they unknowingly get Newt, who carries a sock full of toys with him wherever he goes. When brought to the company, Newt as Hugo starts playing with his toys on the floor, and the entire company rushes to figure out what it all means, what this genius is trying to tell them.

Horton, on the other hand, heads home to Wally’s home life, a life where the “old Wally” gets bossed around by both his wife and his son. When they try and pull that bullshit on him this time, he tells them that if they ever fuck with him again, they’ll regret it for the rest of their lives. Wally’s home problems: solved.

Wally, on the other hand (who’s now in Horton’s body), finds himself as the head of an organized crime ring, and his tough guy underlings are confused about his new nice-guy managing style. The professor, meanwhile, is brought back to Newt’s house, a place where Newt is assumed to be retarded. Which, of course, becomes very confusing when “Newt” starts solving math equations that would frustrate Will Hunting.

When an outside U.S. military division suspects something is amiss in the town of Newtonville, they send a couple of guys out there to get to the bottom of it. But it might be too late. Our characters have already turned, and it’s only a matter of time before they undo the balance of the town and the military establishment that birthed this horrid experiment.

There’s actually a lot more to this story (more characters – more body switches) but to try and summarize them all would require the help of Michio Kaku and Neil deGrasse Tyson. There are people dressed in Heinz bottles, a roller skating rink where everyone skates in rhythmic unison, and an obsessive thread where everyone keeps complaining that there’s “no cheese” in town.

So did it work?

Well, I’ll say this. This is easier to follow than your average Lynch movie. That’s probably because Lynch has a co-writer this go-around. When you don’t have to explain anything to anyone, you can follow whatever whim you fancy. But if you have a co-writer, he needs to know what you’re doing so he can do the same.

The simple act of having to explain yourself requires you to follow some sort of logic, and that’s not how Lynch prefers to write. As a result, there’s something of a story here. I’m just not convinced it’s very good.

Body-switching movies are essentially dramatic irony movies. We know who the person in the body is, but the other characters do not. This allows for a lot of fun scenes that write themselves. For example, we know that Wally’s wife and son run his life, that they bully and berate him every day. So when a cold-blooded killer shows up at home that night in Wally’s body, we know mom and son are in for a world of hurt.

The problem with the premise is that Lynch and Frost are trying to bullshit us. “Bullshitting” is when you fudge something you know you shouldn’t be fudging and hope the reader either doesn’t notice it or goes along with it. The thing is, the reader always smells the bullshit. You might get it past a few really dumb people, but any reader or audience member worth their salt is going to smell your shit from a mile away. I’m going to say this once: You’re not as sly as you think.

The bullshit here resides in the form of the body-switching rules. The switches allow for every single trait of the characters to be transferred into the new bodies EXCEPT their knowledge that they’re in a new body. This becomes a major plot hole because how are we supposed to believe that a contract killer isn’t all of a sudden aware that he’s not with his gang anymore, but hanging out in a middle class suburban home with a wife and son?

It doesn’t make sense. And eccentric directors like Lynch shouldn’t get a pass just because they’re weird. I’m fine with doing the crazy dance on your pages. But you can’t bullshit us on the major hook of your story.

Speaking of story, while this is more coherent than most Lynch films, it’s far from perfect. The body-switching and subsequent division of characters into their new lives is just a reaction to this laser beam event. Once that’s happened, the characters lack a point or a goal.

Lynch and Frost attempt to bring in this second military presence to draw the story to some sort of conclusion, but it’s a half-hearted attempt at best. It comes in so late that we’re not even sure what the military’s goal is or what they’re trying to do. Stop it? Turn these four people back to normal? Does that really matter?

And I think that’s the most telltale question of all. “Does it really matter?” If fixing the problem inherent in your story (in this case, the body switching) doesn’t matter (or only barely matters), that means there are no stakes to the story, which would explain why, when you read One Saliva Bubble, you’re not ever engaged.

Think about this in terms of Tom Hanks’s “Big.” If he doesn’t change back, he misses 30 years of his life. He never gets to see his family again. There are some real stakes attached to him not going back to his kid body.

This would also explain why the script is 140 pages. Usually, when don’t have some sort of structure in place to push you towards the third-act climax, you just keep writing more and more scenes. And why wouldn’t you? If your characters have nowhere to be (no problem to fix, no goal to achieve), you’ll naturally just keep exploring the premise (in this case, body switching).

So where does One Saliva Bubble fall on the Weird Scripts Week scale? That’s a great question. I think it lands at number two behind “Bessie.” It’s a weird script, but it’s not Lynchian weird. I’m still debating whether that’s a good thing or a bad thing.

Script link: One Saliva Bubble

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Playing something as a gimmick compared to playing something as authentic. When you play a concept as a gimmick, you won’t be able to explore your characters in a meaningful way, and, as a result, those characters will never resonate with your audience. So here, Lynch and Frost choose to play their premise as a gimmick. You could almost call this “The Zany Adventures of Four People Who Switch Bodies After Being Hit by a Laser Beam.” For example, the writers aren’t interested in, say, Horton the Killer learning to take care of a family for the first time in his life. They just want to show the fun scenes of a school bully beating up the son character so that our contract killer in disguise can square off against the bully and make him piss his pants. And I’m not saying those scenes aren’t fun. But they’re surface-level scenes. Unless you’re reflecting on how the unfamiliar experience you’ve put your character in CHANGES that character, you’re not really exploring that character or making them compelling to the audience.

While most of this week’s scripts have been forgotten by Hollywood, this one was recently chosen by a major star to become his next big project.

Welcome to Weird Scripts Week! This week I’ll be reviewing odd scripts, odd ideas, and writing that’s just plain odd. It will culminate Friday when I review the strangest premise I’ve ever reviewed on Scriptshadow. To check out Monday’s cross between The Terminator and Jaws, click here. Yesterday’s talking cow screenplay can be seen here. And today, we head to the land of musicals.

Genre: Dramedy/Musical

Premise: When a buttoned-up company man is involved in an accident, the world around him becomes one giant musical number.

About: Bob The Musical is a project that’s been kicking around Hollywood for many years, likely due to its tricky tone. Whenever you’re dealing with something this unusual, every inch of the script is going to be scrutinized until it feels right. And with “Bob” being drafted by more writers than the perpetually developed “Akira,” we’re thinking they want to make sure this one’s just right before going forward. Tom Cruise to the rescue! Cruise attached himself to Bob recently, which means one of his writers will be brought in to write the definitive version of the film and they’ll go forward whether the thing’s ready or not (the power of the movie star!). This is an old draft of the script (couldn’t find a new one) but the concept’s so unique, I had to check it out. I have no idea how close this draft will be to the final film. The script was written by Mike Binder, who gave us films like The Upside of Anger and Reign Over Me. But there have been many drafts since.

Writer: Mike Binder

Details: 112 pages (undated – but I think this draft is about 10 years old)

Now you’d THINK that Mr. Cruise would’ve exited musical theater after Rock of Ages. But we’re talking about a guy who’s navigated a 30-year career in Hollywood, and he seems to understand something a lot of other stars who have faded don’t – which is that if you keep doing the same thing over and over again, you’ll be forgotten.

With films like Rock of Ages, Edge of Tomorrow, Valkyrie, and now Bob the Musical, Cruise is taking chances. And maybe they don’t all pay off. But you’d much rather go down swinging than get walked. Even his Mission Impossible franchise reflects this, as each entry feels a bit different from the last. Let’s see how this one shapes up for him.

Hit it, Charlie!

Stiff-as-a-board Bob Bowman works for one of the richest men in Philadelphia, Ronald Gold. The Trump-like Gold wants to build a brand new skyscaper. But he’s given his team an impossible task. He wants his building on LAKE FRONT PROPERTY.

The thing with Philadelphia is, all the lake-front property is protected by these historic landmark clauses and can’t be purchased. Except for one building, Bob learns. A single building is a week shy of hitting the required 100 year mark to be considered “historic,” which means if Bob can get them to sign a deal by Friday, he’ll become partner.

Bob goes to check the building out, which houses a struggling theater run by the nicest woman in Philadelphia, Mary (when faced with cutting her actors’ salaries due to slow sales, she opts to absorb the hit in her own paycheck – awwww).

It becomes clear to Bob that in order to secure this building, he’ll have to lie to Mary, pretending to be interested in the arts, get her to sign a partnership deal, then use Gold’s legal muscle to wrangle the property away, bulldoze the hopeless theater, and build his partner-making skyscraper.

However, on the way out of that first meeting, one of the old Gargoyles from the building falls onto Bob, knocking him out and sending him to the hospital. When he wakes up, he starts hearing… music. But not just any music. The people around him, they’re…. SINGING. And… DANCING.

When he’s riding down the elevator, a kid starts rapping how his mom won’t leave him alone. When he walks to work, the city becomes one giant song-and-dance routine. When he gets to work, his secretary sings a tragedy about how she hates her boss (Bob) more than anything. When he goes to a basketball game and a fight breaks out on the floor, the players segue into a scene from West Side Story.

While Bob is understandably freaked out, he realizes that this is a new part of his life, and that he must fight through it to close the building deal. But when he starts to fall in love with Mary, and the song and dance numbers become more invasive, Bob will come face-to-face with his own song, a song where he can either croon his way to partner, or Celine Dion his way into Mary’s heart.

The setup for this script was actually pretty solid. Weird Scripts Week has been an exercise in sloppy screenwriting, but Binder sets up a tight story, cluing us in on who Bob is (very selfish and uptight), what he wants (to be a partner in Gold’s company) and what he needs to do to get it (cheat the girl he’s falling in love with to sign a deal that secretly gives Gold control of her building so he can tear it down).

This conflict of needing to lie to a character you’re falling for in order to achieve a goal is a well-worn trope, but when done well, it usually works. And it works here up to a point.

Bob the Musical begins running into trouble in its second act, where it gets stuck somewhere in between a Charlie Kaufman joint and a 1990s Jim Carrey comedy. Things eventually become so formulaic (Mary gets mad at Bob and states the deal is off. So Bob must apologize and try a new approach to get her to sign!) that the brilliance of the premise loses its luster.

Even the songs and dances start becoming predictable, with the tough pissed off teenager spouting out, of course, Eminem-style raps.

And this is where a lot of these scripts die, in fact. With writers playing things too safe. There’s a form of execution in these screenplays that’s just cute enough to get a polite smile from the reader, but not big enough to impress them. And Bob The Musical starts to feel like one big polite smile. I remember specifically that polite smile on my face with the West Side Story scene.

If I know screenwriters, they’d be more okay with a woman telling them post sex that their manhood wasn’t big enough than to hear that someone “politely smiled” while reading their script.

It goes back to the “first choice syndrome” we talk about here. On a clever premise like Bob the Musical, you can’t use first choices. You have to throw those out and think of something crazier. And then throw that out and think of something crazier! Really push yourself because that’s the only way you’re going to get to those truly outrageous memorable ideas.

Even more so in scripts like this. I mean, if you have a weird or crazy premise, why would you restrict it? Why would you play it safe? If you’re making a movie about being inside John Malkovich’s head, you want a scene that includes a 7th and a half floor.

That’s not to say you throw all rules out the door. You still need some structure and focus to keep the story on track. But you don’t want to be the false advertiser. You don’t want to promise your audience something and give them something else. That’s the fastest way to get a crowd to turn on you.

With that being said, this script has always had an uphill battle. It’s one of those stories that you don’t truly know if it’s working until you see it on the big screen. We need to hear the music, hear the singing, see the dancing, in order to ingest the power of the storytelling, and that’s just not possible on the page. So I have sympathy for the project and this draft that Binder wrote. But I still wish he would’ve done more with it.

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Drop CLUES to help your reader know who your hero is. When a reader reads a script, one of the first thing’s he’s looking for is CLUES about your hero. What is the hero doing? How is he acting? What does he say? We’re trying to figure out who this guy is and the clues you drop are going to tell us. For example, one of the early description lines in Bob the Musical is, “Bob rounds the corner, looking serious as usual.” That phrase there, serious as usual, sticks in our head. Later, someone’s on the street singing. Bob, who’s talking on his phone, covers his free ear and STARTS TALKING LOUDER. Another clue. He’s easily annoyed. Then later, after a co-worker expresses excitement about something, we get this line: “Bob walks out of his office displaying no emotion at all.” Just by highlighting those three clues, I’m betting you already have a great feel for who Bob is. Yet most writers, and in particular amateur writers, are very vague and general when describing their hero or conveying his actions. Without those vital clues, we never get a feel for who he is, and we go through the story imagining some vague figure leading us. It’s only a matter of time, then, before we become bored with them.

What I learned 2: One of the craziest realizations to come out of this week has been how influenced we are by the times. Especially with yesterday’s and today’s scripts, where you could FEEL the late 90s influences guiding these writers’ choices. I mean Bob The Musical was hitting Liar Liar and What Women Want story beats almost to the tilt (After hearing their struggling inner songs, Bob shows up to work and starts paying attention to people and complimenting them). So when you’re writing your script, think into the future. Ask yourself, will someone who reads this in 2030 be like, “Oh my God, this feels so 2015.” If so, you’re probably being too influenced by the films of the moment. Try to look for other inspiration to stand out. Movies from the 1960s, 1970s. Unique paintings. Strange music. Find inspiration that allows your screenplay to feel unlike anything that’s out there right now.