Genre: Drama

Premise: A single mother and her family struggle to make ends meet in a dying town that finds itself descending into madness.

About: Lost River is the writing-directing debut of actor Ryan Gosling. Gosling put together a stellar cast that included Christina Hendricks, Saoirse Ronan, and Eva Mendes. The script played a couple festivals but the consensus seemed to be that while ambitious, the movie is a miss. It came out this weekend and currently has a Rotten Tomatoes score of 31%. The script (formerly titled, “How to Catch a Monster”) first came to my attention when it finished extremely high on The Hit List, a list of the best specs of the year. However, it was conspicuously absent from The Black List, which was released a few days later. Was the script great? Was it terrible? Who knew? Well, it was time I knew. And hence, today’s review!

Writer: Ryan Gosling

Details: 101 pages (April 19, 2012 draft)

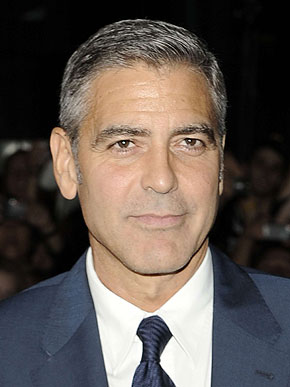

Most people would argue that Ryan Gosling has it all. He’s handsome. He’s a movie star. He’s one of the few big actors in Hollywood who hasn’t sold out. Oh, let’s not forget he’s married to one of the most beautiful women in show business. So when the man decides, “Hey, I’m going to write and direct a movie cause why the hell not,” the response was probably akin to the way the DJ world embraced Paris Hilton when she decided to become a DJ.

And they have a point. I mean let’s pretend we’re there to watch Ryan casting his film. What if a screenwriter showed up and said, “I’d like to play a major role in your movie.” We’ll even give this writer the benefit of the doubt. Let’s say he has the perfect look for the part. So Ryan responds, “Well, have you ever acted before?” “No,” he says, “But I watch a lot of movies. And I write a lot of scripts, so I understand character.”

Do you think Ryan would cast him? I’m guessing not. My gut tells me he’s going with a much more experienced actor. Why? Because he knows how hard acting is. Because, after putting all that time and effort into becoming the great actor that he is, he knows how intense one must train as an actor to become great at it.

So then why does he think screenwriting would be any different? I would argue that becoming a good screenwriter is much harder than becoming a good actor. 99.99999999999999% of the people on the planet can’t keep a reader’s attention for more than 2 minutes on the page.

That’s not to say you can’t have crossovers. Matt Damon writes. Ben Affleck writes. Chris Rock writes. Actually, Chris Rock’s debatable. But in any case, these are guys who have always been writing, who came into the business as double-threats. I confess I don’t know the specifics of Ryan’s background, but it seems like he just decided to write a script one day. And whenever you’re someone successful who enters another space, people are waiting to jump on you. Especially people on the internet, which might as well be called Haterverse.

I’m going to try and not be one of those people. I want to read this screenplay objectively. I just have a lot of respect for how difficult it is to write a good script. Therefore it’s hard for me to see people who haven’t gone through the trials and tribulations of struggling through this craft without a skeptical eye.

Billy, on the cusp of the big four-o, knows her stripper days are numbered. And it couldn’t come at a worse time. She’s days away from losing her home and doesn’t have many skill sets to change that fate. Any that don’t include polls that is.

Her only shot is a loan and, ironically, the bank manager she needs to convince happens to be the guy she made fun of back in high school when she was the mean hot chick. But Bank Manager Guy doesn’t hold grudges, and offers her a job at his new unique facility, a sort of live theater house with some weird shit that goes on in the basement.

Billy takes the job because… what else is she gonna do? In the meantime, her teenage son, Bones, is running around trying to avoid the town bully, whose name is literally “Bully.” Bones finds spiritual solace in learning that a former town from the 1950s is buried under the nearby river and starts spending his time diving underneath the river and exploring it.

We’ve also got Rat, Bones’s teenage crush who lives with her formerly famous actress grandmother who now watches her old silent movies on repeat all day. If you stop them she begins a high-pitched scream that doesn’t end until you start them again. And we’ve also got Frankie, Billy’s 4 year old son who’s… SUICIDAL! Yes, Frankie dreams of getting run over by a car so whenever he’s near a street he runs into it, hoping to get hit.

That, in a nutshell, is Lost River.

Gosling maybe should’ve titled this “I’m Lost River,” cause that’s how I felt half the time. The thing is, the script isn’t that bad. It’s just that Gosling makes a classic amateur blunder, one that pretty much every beginner screenwriter makes for their first few screenplays. That’s that he builds the story way too slowly. Everything takes forever to happen. If he would’ve just sped it all up, this might have been a good movie.

Case in point. The script’s most compelling element was this old underwater city. Ask me what page this city first gets mentioned. Page 10? No. Page 20? Nuh-uh. By page 30 at least. No. 40? Nosir. It isn’t mentioned until page 50!

Wha???????

You’ve even titled the script after this underwater town. Why isn’t it mentioned until the film is halfway over???

In addition to this, we have the Wolf Playhouse and its sketchy basement activities. This part of the script also had some cool ideas in it. Billy’s job is to get inside this clear bullet-proof shatter proof super-reinforced coffin of sorts. Men then come into the room and take their rage out on you. They can do whatever they want, except touch you, obviously, since you’re protected by this super-coffin.

But that storyline doesn’t truly get started until around page 75. With just 25 pages to go in the script!!! Naturally, the rest of that storyline feels rushed. This is a classic structural problem and something that if you don’t write a lot of screenplays, you’ll likely screw up.

I was recently explaining to a writer that anybody can ramble a story together over 150 pages. Just by the mere fact that you’re continuing to type, you’re going to carve together a story at some point. What the pros do differently is they make sure every scene has a strong reason for being there. This ensures that the story is tight and focused.

One of the easiest ways for me to tell if a writer knows what he’s doing is to read the first few pages of his script. A good writer makes you feel like you’re going somewhere right away, like there’s a meticulous design being laid out. Inexperienced writers just sort of write scenes until they come up with an idea for a good scene. They then, inexplicably, keep the previous four or five pointless scenes, believing those scenes justify themselves by the mere fact that they inspired the relevant scene. That’s not how screenwriting works. You have to jump into your story right away and never waste space.

The rest of Lost River is a mixed bag of floating debris. Gosling is trying to create something deeper and more thoughtful here, but it’s not entirely clear what that is. He gives his characters names like Bones, Bully, and, Rat. He’s got the big bad wolf play theatre. Rat lives in a “nest” inside her hoarder grandma’s house. The Lochness monster even makes a cameo. So I guess it’s like this fairy tale but because the script takes so long to find itself, none of those symbolic references register in any meaningful way. In fact, they often feel on-the-nose and silly.

And then you just have weird choices like a suicidal 4 year-old obsessed with getting hit by a car. When Frankie escapes from school to run out in the street and get hit, Billy confronts his teacher with this line. “You fucking bitch.” The teacher’s response: “I have never, in my entire career, dealt with a child who was hellbent on getting hit by a car. It’s all he wants to do. You ever ask yourself why your son has a death wish at four years old?” Not gonna lie. Almost put down the script after that one. And are 4 year-olds even capable of suicidal thoughts? This didn’t make any sense to me.

I wish Gosling would’ve let a professional screenwriter write this for him. There are some genuinely cool ideas in here. But ideas without focus are just ramblings. And that’s a bit what Lost River felt like.

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Whatever pace you’re setting up your story at, chances are it’s slower than it needs to be, especially if you’re new to screenwriting. This is why you hear all these rules like “combine scenes” and “only write scenes if they’re absolutely necessary.” It’s all to move the story along faster so that you keep your reader interested.

After yesterday’s spectacular surprise, the buzz is high for this week’s Amateur Offerings. If you’re too shy to display your script to the world, maybe doing the Scriptshadow 250 dance is a better option. You know how it works. Read til you’re bored. Share your thoughts in the comments!

Title: Guilt

Genre: Dark Comedy (99 pgs)

Logline: A crack-smoking lawyer, witness to a murder, tries to redeem himself by vindicating the teen prostitute wrongly accused of the crime.

Why you should read: Though I’d love to come up with some touching, true-life moment that makes this story personal, I cannot. I simply wasn’t born into the same dire circumstances as those typically faced with the horrors of an unjust justice system. I’m also not a self-absorbed coke fiend like my protagonist. But while this story isn’t a reflection of my life, I know it is for many others, and I hope I was able to capture at least some of that strife, in addition to bringing some moments of ironic hilarity.

I’ve been a long time reader of Scriptshadow, mainly because no matter what the article or review, you seem to provide something fresh every time. You could throw a rock in any direction and hit five blogs on “how to write a screenplay”, or “the 10 mistakes young writers make”, but every one of them seems to just regurgitate the same points. It’s like no one has an original perspective on the business, except you and maybe a handful of others. And to your perspective, I made this script as lean as possible, while creating a fun character that any A-list actor should be dying to play.

My initial goal in writing Guilt was to meld the tragic angst of the Verdict, with the drug-fueled narcissism of The Wolf of Wall Street, along with a healthy GSU, because this young girl doesn’t have long before she’s put away for life.

Here’s what one Blacklist reader had to say: “What makes this script so interesting is how intelligently it tackles the unjust practice of forcing innocents into accepting plea deals. It’s rare to see a comedy that can highlight such a serious social ill while still keeping the laugh factor high, but thankfully, this script does just that. Reginald is a well-developed anti-hero; his heart is usually in the right place, but his actions don’t’ always reflect his good intentions. Though not perfect (see below), his relationship with his daughter Becca is what ultimately grounds Reginald as it gives him the greatest high of all time, one he could never receive from a drug. The dialogue, in particular Reginald’s monologues, is also extremely funny and well-written.”

I hope you find it a fun read!

Who doesn’t believe in second chances!?

Title: The Creation of Adam

Genre: Thriller/Horror

Logline: When Adam, a troubled teenager, learns from his father that they both carry an evil that is passed from father to son, Adam must decide to fight the demon…or become one.

Why you should read: Last year, when my script was featured on AOW, I got a very enthusiastic email from an actor-director who wanted to make the film with his friend, a famous actress, and a couple of other talents from CAA. My screenwriter’s dream was crushed when the actress decided that it wasn’t for her.The director probably went to look for another project to do with her and I was back to writing something new.

Here it is, a thriller/horror script, Shining meets The Omen, a movie I feel so passionate about, I’m willing to cheat the lottery, direct-produce-edit it myself if I need to. So, why should you read it? Because this script has mystery, thrills, horror, very cinematic set pieces you’ve never seen before and a weird father-son relationship gone horribly bad. A reader wrote “This script takes coming of age to a whole new level” Hope you agree.

Title: Drawing Dead

Genre: Crime

Logline: An opportunistic and ambitious sniper-turned-hitman gets the opportunity of a lifetime to fulfil his ambitions when he gets the job of killing the woman he’s falling in love with.

Why you should read: I work in an advertising agency, where I’m a strategist. My best work to date by far has been the strategies I’ve developed for how to appear hard at work in an open-plan office where my screen is on public display. And so, in emails to myself, word documents and in the notes section of powerpoint slides, this script slowly came together. When people were getting too close I’d switch to my native Norwegian, just in case.

Anyways, the script is a blend of three crime sub-genres (all with a twist): the hitman movie (Gen-Y has entered the workforce), the film-noir (the femme fatale and private detective join forces) and the Mafia film (a dysfunctional crime family replaces scare tactics with modern marketing principles).

I can but hope that the whole proves greater than the sum of its parts and that the result is a fresh and interesting read. I hope you enjoy it and I very much look forward to your feedback!

Title: Cielo Drive

Genre: Action

Logline: Taken set against the Manson Family murders. Sharon Tate’s father, an Army Intelligence vet, takes matters into his own hands when he infiltrates the L.A. underground scene in order to find her killer. — Tate’s father do go undercover but it’s never been revealed what he actually found. He was close enough to finding something that the LAPD were nervous about his presence.

Why you should read: My name is Erik Stiller, and I’ve just been promoted to Staff Writer for the upcoming season of CBS’ CRIMINAL MINDS. If you like LA history and revenge-action with a good man doing brutal shit then check out this feature.

Title: THE FUSE IS BURNING…

Genre: Mystery/Thriller

Logline : A troubled man tries to find solace by searching a desert canyon for dinosaur fossils. But everything changes when a young girl is found murdered in the same remote region.

Why you should read: There’s nothing like a good story. And this one begins one hundred sixty five million years ago.

Get Your Script Reviewed On Scriptshadow!: To submit your script for an Amateur Review, send in a PDF of your script, along with the title, genre, logline, and finally, something interesting about yourself and/or your script that you’d like us to post along with the script if reviewed. Use my submission address please: Carsonreeves3@gmail.com. Remember that your script will be posted. If you’re nervous about the effects of a bad review, feel free to use an alias name and/or title. It’s a good idea to resubmit every couple of weeks so your submission stays near the top.

Genre: Comedy

Premise: A vapid beauty queen is abducted by aliens who think her title means she’s Earth’s ambassador to the universe.

About: It’s “Galaxy Quest” meets “Legally Blonde.” Deep space has never been more shallow (Carson note: When everyone pitched their ideas on “pitch your script day,” this idea shot to the top of the list!)

Writer: Colin O’Brien

Details: 106 pages

Alice Eve for Jane? Yespleasethankyou.

Alice Eve for Jane? Yespleasethankyou.

When you put a logline out there for the screenwriting community to grade and the feedback isn’t good, it’s easy to accuse the readers of jealousy, or sabotage, or “not getting it,” or my favorite: “Being wrong.” You know your idea is great. If they don’t acknowledge that, then there must be something wrong with them.

But the reality is, when a good logline gets posted, the community is the first to say so. And I don’t think we’ve ever had the kind of response to a logline as we did with Miss Universe, which first lit up the comments section when we did “Pitch your screenplay” Day. Everybody loved the idea. The only problem was, Colin hadn’t written it yet. So he went back to his pot of gold and made the long trek over the rainbow so we could finally read it.

It should be noted, however, this is a comedy logline. I’ve come across more great comedy loglines that turned into garbage screenplays than any other genre. It just seems easier to come up with a funny comedy logline than in any other genre. But it’s harder to write comedy than any other genre. So as excited as I was for Colin’s idea, I’d been down this road before.

I should add that Scriptshadow hasn’t always been a bastion for comedy discoveries. We had I Am Ryan Reynolds up for Amateur Offerings and the readers ignored it. The script would later go on to make the Black List. So as much as I love our readers who point out grammar errors on page 37, I want the comedy guys to show up today. I want the funny dudes to reach out and tell us what they think.

24 year-old Jane Breslin isn’t the brightest star in the universe. But that doesn’t matter if you hold the title of Miss Universe. Which Jane does. And boy is she excited about it. Her guido bofo Lyle, however, hasn’t been too excited. The last year has been a whirlwind of pageants and Jane’s rule of no sex during competition has left him… how do you say? A little blue in the nether region. But now that Jane’s won the final prize, he can FINALLY do a little copulation nation.

That is until Jane’s beamed up to an interplanetary spaceship of misfit aliens who think she really is Miss Universe – as in earth’s leader. Jane’s been called upon by alien Captain Hazz Mathers in hopes of negotiating the end of a universal war with Queen Kar-uton, the leader of the lizard people – known best for invading unsuspecting planets and turning them into giant dust bunnies.

When Jane can’t speak the Kar’uton’s native tongue to save their asses, Hazz realizes he may have made an oopsies. But it’s too late now. His trip to earth has piqued the Kar-uton’s interest, which they’ve now decided to invade and destroy.

They do this by sending a fake Jane down onto the planet to have sex with as many earthlings as possible so she can start laying alien eggs that will soon hatch, birth an alien army, and spell the end of mankind.

In the meantime, Hazz takes Jane to his old planet, which has since been destroyed by the Kar’uton. It’s there where she meets the planet’s former King, who it turns out… IS HER FATHER. Not sure how that happened. He informs Jane that she has the power to make a difference, inspiring her to jet back to earth with her alien misfit buddies and save earth. And with it, the universe!

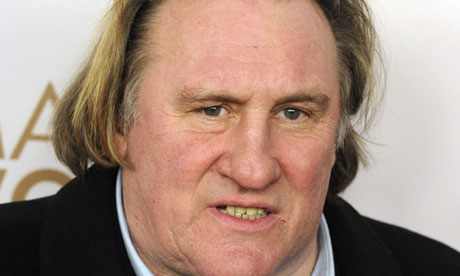

Gerard Depardieu for one of the aliens. Keeps the make-up budget low.

Gerard Depardieu for one of the aliens. Keeps the make-up budget low.

I have a prediction. I believe that with the help of the Scriptshadow community, Miss Universe can become a movie. It hits that perfect sweet spot between Galaxy Quest and Ghostbusters. Along with a female lead (the new hot thing in Hollywood), and a great hook, this script has all sorts of market potential.

But it’s not there yet. And that’s okay. Comedies like these need to be work-shopped. You need to identify the stuff that’s not funny, get it out of there, and try something else. If you keep doing that and keep eliminating the least funny stuff with every draft, you can get something really good at the end of the process.

Here’s what worked for me. Alien Jane. Alien Jane was AWESOME. I actually thought the first act was too textbook. It felt like I was in a Blake Snyder seminar. But when Alien Jane showed up and started casually telling everyone that she was here to destroy earth, I started laughing. Hard. I loved the media coverage of her as well. That’s exactly what would happen if an alien Miss Universe did a press tour!

I thought the tone was solid. I thought most of the characters were great (and imaginative). I thought little touches like Bott being self-conscious that he was a cyborg were great. And I thought that Colin got a lot of out of the premise. It wasn’t perfect but he did more with this than a lot of writers would’ve done.

Here’s what I didn’t like. First, make it clear that Hazz is an alien! He’s introduced as “goofy-handsome” and I just assumed he was human. Which destroyed the whole point of the premise. Why wouldn’t a human know that Jane wasn’t actually an ambassador to the universe? It was only over time (not because of the writer) that I gathered he was alien. That’s an easy fix but a really important one.

Next, I didn’t like the King being Jane’s father. To put it bluntly, I thought it was stupid. And I lost a lot of faith in the script once that happened.

But when I took a step back, I realized it wasn’t just that that disappointed me. It was the entire storyline up in space. WHAT WERE THE CHARACTERS DOING UP THERE??? They had no direction, no purpose. All the fun and important stuff was happening down on earth. In the meantime, our main character’s biggest objective was playing matchmaker to a couple of crew members!??

That’s a subplot! It should not be a main storyline in the movie.

The biggest change that needs to be made here is that the up-in-space characters need a GOAL. That goal needs STAKES. And that goal and those stakes need URGENCY. I have an idea that isn’t very good but maybe it’ll get you started. Maybe, in that initial fight with the Kar’utons, they have to make an emergency light-speed jump to avoid being blown up. In the process, their ship breaks down and they’re stranded. With Alien Kate quickly populating earth with killer alien eggs, they only have hours to figure out a way to get back and save mankind. And it needs to be your main character who’s instrumental in figuring out how to do that.

I think Colin can come up with something way better than that. I’d like more movement in space if possible. But the point is, you need a storyline that FEELS IMPORTANT up there. Right now, everyone up in the alien ship just seems to be hanging out.

Scriptshadow Nation – I implore you to help Colin out. Read this script. Or hell, just read the logline. Then give Colin funny ideas to make this better. Those of you who don’t like commenting, at least upvote the ideas you think are funny. Let’s help Colin turn this into something great. I think it has loads of potential!

Oh, and one last thing. A writer e-mailed me to demand that the title of this be changed to “Miss Universe Saves the Universe.” The same writer proposed the title change to Colin but Colin doesn’t like it. So please vote which title you think is better in the comments.

Screenplay link: Miss Universe

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Relationship exploration needs to happen AROUND THE PLOT. It can’t BE THE PLOT. The entire second act stopped so that Jane could help Bott try and land his crush, Zumba. I actually liked that story thread. But it’s not big enough to drive the entire up-in-space story. There needs to be something bigger they’re trying to achieve, and then Jane’s matchmaking needs to take place around that bigger objective. Look at Han and Leia in Star Wars. All of their relationship development occurs as they’re trying to achieve bigger things. The movie never stops to center on them just chatting. In the later sequels of the series (Return of the Jedi), when the writing got worse, it did stop to center on them. It’s no coincidence that the relationship became less interesting in the process.

It’s time for another edition of “Didn’t Get Picked.” It’s often debated how much query letters matter. I’m here to tell you that THEY DEFINITELY MATTER. As someone who receives a ton of queries (for Amateur Offerings, for The Scriptshadow 250), I assure you, I can determine a lot from a query. In fact, I have an unofficial checklist of how I go from e-mail to full script read. It starts with me opening the e-mail. This is what happens next.

1) Can the writer put together basic sentences without any errors? If so, go to 2.

2) Is the query well-written? Does it display thought, care, passion? If so, go to 3.

3) Does the writer know how to write a proper logline? If so, go to 4.

4) Is the idea a good one? If so, go to 5.

5) Read the first page of the script. Does it pull you in? If so, go to 6.

6) Read until page 5. Is the script still keeping you interested? If so, go to 7.

7) Read until you get bored. If you’ve done your job, I will not want to put your script down until the last page.

Obviously, you can’t get to number 7 without first getting through numbers 1-4. I’d say about 50% of the queries I read don’t get past number 2. But if you get past number 2, there’s a good chance you know a good idea from a bad one. Or that you can at least craft a solid logline. So, many who get past 2 at least get me to read their first page. Of the people who get that first-page read, I’d say 25% of them get past number 6 (read at least five pages). Of those who get that far, I’d say I finish about 5% of those scripts. And I’m guessing the industry average is similar.

The lesson here being that nobody even touches your script unless your query letter and logline are solid. The frustrating thing about this is that writers don’t receive queries. So they have little reference for what it’s like to read a query letter. How can you get good at something if you can’t study it? Well, that’s what today is about. I’m going to put up some real-life queries that were sent to me and explain why they didn’t make the cut. We’re not here to bash people or to tell them they suck. We’re here to help each other learn. Let’s get started!

SOCCERROCK by xxxx xxxxxx

A retired pro soccer player from the United States has his career

resurrected to help the British Secret Service capture an elusive

terrorist cell and Kris Sanderson is also reunited with Dead Egypt,

the world’s most famous heavy metal band.

The world’s most popular sport is soccer. More countries are

registered with soccer’s governing body, FIFA (Federation

International Football Association), than in the United Nations.

From the slums of Argentina, to the sub zero temperatures in Siberia,

someone is playing soccer as you read this. Since the days of Elvis

Presley, to the sold out stadiums featuring Metallica, rock & roll

music is a global phenomenon. When you combine these two genres, the

results are electric and this is truly an original concept. Almost

every soccer movie ever made involves kids and cute animals, and is

usually a G-RATED affair. Every other sport has films of a more adult

nature. Hockey has “SLAP SHOT”, baseball has “MAJOR LEAGUE”, football

has “THE LONGEST YARD”, and golf has “TIN CUP”, just to name a few

examples. Where is the great adult soccer movie?? Using my experiences

as a professional soccer player for twelve years, as well as being a

sports writer and roadie for rock bands, SOCCERROCK is an

action/adventure story that is void of all the corny formulas that

exist in every Hollywood soccer production.

You want to start out a query letter by introducing yourself. Even if it’s a quick introduction. To jump right into your logline without saying anything is jarring. I’ll excuse this if the writer uses my format preference (genre, title, logline, why you should read), but as you can see, that wasn’t the case here. As it turns out, I didn’t have to read any further to know that the script was in trouble. As passionately as the writer pitches his project, the logline indicates a story so unfocused as to be unreadable. From my experience, if a one-sentence logline is unfocused, the script will be extremely unfocused. There are three separate ideas here. A soccer idea. A heavy metal band idea. And a British Secret Service idea. True, the mixing of these elements is what makes the idea unique, but that doesn’t matter if the script sounds all over the place. I’d encourage the writer to focus on one subject with his next script.

Hi,

thanks for taking the time to read this email (and hopefully the script). I’m a Welsh based writer working in the tv industry as an assistant director. For the past two years I’ve placed in the quarter finals of the Nicholls with this script, and have used the notes from them to improve the script to get it to a stage where I think its ready to be pushed out into the industry.

This is where you come in Mr. Reeves. Hopefully you’ll agree and feature this script on your website and offer some good notes. I look forward to hearing back from you.

Title: Big Red

Genre: Sci-Fi / Family

Logline: Erin is a child orphan who runs away with a fugitive robot to find a new home.

Okay, so this time we have someone who greets me! That’s good! Unfortunately, the first letter of the opening paragraph isn’t capitalized. That tells me the writer hastily sent this query out and therefore doesn’t care enough about the craft. Later I also see an “its” instead of the correct, “it’s,” and that pretty much ensures the submission won’t make the cut. I’m looking for writers who care, who take this seriously, and who put effort into the written word – ALL the written words. Finally, the logline doesn’t introduce any conflict into the story. Someone runs away with a robot. But then what happens to ruin their plan? You need to include the key conflict in your logline.

Carson,

Hope your weekend was productive. I’ve been a fan of your site for nearly five years. It’s been a huge part of my screenwriting education. Below are the details of my Amateur Offerings Weekend submission.

-MAQ

Title: Page Turn Her

Genre: Drama/Comedy

Logline: A love-struck ad writer finds a magical journal that controls his unrequited crush’s actions, but he hesitates using it because the men who get close to her have a tendency to die.

Why you should read: I’m a longtime Scriptshadow reader whose last script, “King of Matrimony,” made it into Amateur Offerings Weekend. Based on the comments, I thought it would have been selected. Regardless, this new script is better in every way.

I have to give it to Michael. The man is persistent! He consistently submits his script every week, so I feel like the least I can do is explain why I haven’t chosen him. This is actually a pretty strong query. Michael keeps the introduction brief and catches my attention with flattery (been a fan of the site for five years). He can obviously write a clean sentence. There isn’t anything wrong with the query itself. It’s when I get to the logline that I have a problem. The logline starts out as a sort of magical What Women Want type film (ad writer who finds a magical journal that allows him access to his crush) but then becomes something much darker at the end (people are dying??). Put simply, it feels like a confused idea. Making matters worse is that it’s listed as a “Drama/Comedy.” So in addition to the comedy element (magic journal) and thriller element (people dying who get too close), there’s also a dramatic element? I don’t know if this idea needs to be scrapped or Michael just needs someone to help him focus it. But for future reference, you want your idea to be clean and easy to understand. If it results in even the slightest bit of confusion, rethink it. Hopefully this helps, Michael. And keep writing!

Title: The Psycho Sweethearts Reality Show

Genre: Dark Comedy/Satire

Logline: A reality show follows newly wed husband and wife serial killers as they try to keep their sanity as their celebrity increases.

Writer: Writer’s Anonymous

Why You Should Read: I was chatting with a group of friends when reality shows came up. I watch NOT ONE currently and never will again which I’m extremely proud about when a idea hit me.

Hey, maybe, I would watch a reality show if it were on street gangs, mafia, drug cartels, serial killers, spies, banksters or even the Illuminati. That idea thoroughly cemented in my head, I decided to try this idea for my next script. Finished the first draft in a month and rewrote it a month or two later. I believe I have something “SPECIAL” for the Scriptshadow community though I readily admit may be a draft or two away.

Scriptshadow community, you’re happy to run with the other ideas if you want.

This is a superficial script on superficial couple in a superficial world and I need all the constructive criticism you can give me.

I tried to keep the formatting of the e-mail to show that it had 2-3 line spaces between each section but it wouldn’t stick. Wonky formatting is an easy way to dismiss a writer. If you want to know how your e-mail is being seen, open up another e-mail account (if you’re on gmail, get a Hotmail account) and send your query to that e-mail. It’s an easy way to see how your query looks.

There are some other red flags here as well. How are you going to write about something you know nothing about? Just about the only way to give us an authentic story is to know as much about your subject matter as possible. Case in point: I think there ARE reality shows for all the subjects he mentions but because he doesn’t know anything about reality shows, he doesn’t know that. This said to me this was more of an experiment than a script the writer actually cared about. The last sentence also has an error in it: “This is a superficial script on superficial couple in a superficial world…” Writers have to remember that this is a PROFESSION they’re trying to break into. So you have to present yourself and your script professionally. If you didn’t put 100% effort into a 200 word e-mail, there’s no way you put it into a 20,000 word screenplay.

Title of script: HIT YOURSELF

Genre: Thriller / Dark comedy

Logline: When a retired hitman is hunted by his former employers for refusing to kill a homeless witness, they murder his best friend, causing him to seek revenge by writing a book, exposing their secrets to the public. But when it fails to sell, he is forced to pick up the gun, one last time.

Why you should read my screenplay:

This being my very first attempt at screenwriting, I feel it is a good example of just how much one can learn within a six month period. While the story itself went through several changes, the characters do not let their fictional roots ruin their ability to feel real.

The ghetto / drug area setting is very real, as I used real life experiences for my backdrop.

My style differs from the everyday writer, as I tried to take risks which I knew could either lose the reader, or keep them interested.

The main story and subplot blend together nicely, with some great twists. The further you read, the more things make sense, and things you thought seemed pointless become clear, up to the final image.

Finally, while it is a fairly simple story, showing how karma really can be a bitch, no matter how guilty you feel for your actions, it still manages to challenge you, as you keep track of timeline jumps and plot points that make you realize that what you thought you knew, was wrong. Not everything is what it seems.

Thanks for your time!!

Phil Golub

This isn’t a bad query. But there are a few reasons I didn’t pick it. First, the logline is more summary than logline. A logline sets up your concept, your main character, and the main conflict. It’s very succinct. This one rambles. You can also spot some story issues within it. Everything seems okay when we’re talking about a hitman being hunted, but then all of a sudden someone is writing a book? And we have to wait for that book to be released before the real story can begin? Writing and releasing a book takes, what? 6-12 months? What are we doing in the story during that time? Watching the character write? That’s not going to sell any tickets. You could do a time jump over this period, of course, but then you have a big weird time jump in the middle of your movie. Hitmen movies shouldn’t have time jumps. They should happen within a contained time frame. Imagine if Taken had a 1 year jump at the midpoint. It wouldn’t be Taken. As if to confirm my fears, the writer than tells me this is his first screenplay. I get that some people use Amateur Friday to learn. But you don’t want to tell anyone this is your first script in a query. Everybody in the business knows that first scripts are terrible (with the rare exception – usually from writers who have written in other mediums). So the query reader immediately loses faith in you. Finally, the “why you should read” reads too formal (“I feel it is a good example of just how…). There’s a lack of freedom to the writing that tells me the script will feel the same. Writing should feel effortless to the reader, not like you’re proving a point in a senior thesis.

To all the writers whose queries I featured today: Don’t let any of this discourage you. You’re now armed with more knowledge so that your next script and next query will be better. As long as you love screenwriting and dedicate yourself to it, you’ll eventually write something great and pitch it perfectly. But you need these speed bumps along the way to learn how to do it right.

Genre: Independent/Romantic Comedy

Premise: A Texas Lottery fraud investigator investigates a woman who has won the lottery three times, which amounts to septillion-to-one odds.

About: The hottest spec in town right now is Septillion to One. The quirky story has Alexander Payne circling and as soon as you get Payne onboard, you’re in the Oscar discussion. Which means the script will probably get someone like George Clooney for the lead, and I’m guessing Olivia Wilde for the co-lead. But what about our writers? Well, the writing team consists of Adam Perlman, who wrote on Aaron Sorkin’s The Newsroom, and Graham Sack, who doesn’t have a writing credit to his name. Sack was a child actor, however, known for such movies as Dunston Checks In and Miracle Child.

Writers: Adam R. Perlman & Graham Sack

Details: 119 pages

Many people equate selling a screenplay to winning the lottery. They point out all the scripts registered by the WGA each year and how only 75 of them sell, or something ridiculous like that. The truth is, the odds aren’t as bad as you think. I mean, how many screenplays are really written each year? Maybe 100,000? If 75 of those sell, those odds are a hell of a lot better than septillion to one.

Plus, unlike the lottery, skill factors into the equation. You can game the system with a couple of hacks, dramatically increasing your odds. Writing in one of Hollywood’s favored spec genres increases your odds. Making your main character a male between the ages of 30-50 increases your odds. A high concept increases your odds. If you’ve added enough of these hacks, and you’ve put a lot of time and effort into the craft, your odds of selling a spec aren’t that ridiculous at all.

For whatever reason though, despite KNOWING these hacks, tons of writers ignore them, pushing the odds out of their favor. Doing so will never skew the odds as bad as septillion to one. But they will keep you from becoming the next Septillion to One.

Texas State Lottery Investigator Clark Hauser is a stickler for the rules. And when I say stickler, I mean he went after his own step-father for taking bribes. Of course, that was back when Clark worked for the FBI and his step-father worked for Congress. And it was because his step-father worked for Congress that he was able to pull some favors and get Clark fired for coming after him.

Now Clark is stuck in the miserable position of working for the Texas State Lottery. And to add insult to injury, his step-father has primary custody over his daughter, Megan. Not only that, but Step Daddy wants sole custody. There’s nothing Clark can do for this girl anymore, he points out. If his daughter’s going to flourish, she’s going to need Grandpa’s money.

But Clark’s luck is changing. When the Texas Lottery starts vetting its past winners to find a poster-worthy candidate to sell a flashy new lottery drawing, Clark becomes aware of Joy Taylor’s story. Joy has won THREE lotteries in three different states. The odds of that happening are so astronomical, Clark knows she’s cheating. All he has to do is prove the scam, and his job prospects will go through the roof.

Despite Clark clearly liking Joy, he has always been, and will always be, about the rules. And even as their friendship grows, Clark continues to accumulate evidence that will help him prove that Joy’s a sham. The problem is, nothing he finds sticks. And if Joy is guilty, she seems to be the most casual most unworried suspect in the world. Could it be that Joy truly is the luckiest person in the world? Or is there something more sinister going on here?

Scene construction is one of those quick ways for me to determine whether I’m dealing with an amateur or a pro. If a scene is constructed in such a way that indicates an understanding of the craft, I know I’m in for a good read. If there is no form whatsoever in a scene – just people talking, babbling on endlessly without a point – I know I’m about to check into the Boredasaurus Hotel.

So when Clark first comes to question Joy about her amazing luck, the scene takes place during a bingo game, with Joy as the presenter. Therefore, Clark is forced to ask Joy questions WHILE she calls out numbers to the crowd. It’s little things like this – an element that’s agitating the conversation – that tell me I’m dealing with a pro. You never want to make things easy on your characters, even conversations. This choice may seem insignificant to the uninitiated. But it tells me I have a real writer on my hands.

We have the basics taken care of as well. Clark’s boss wants to use Joy as the poster-girl for the upcoming mega-lottery draw in a week. Clark knows that if Joy’s a fraud, she’s going to destroy the public’s trust in the lottery. So he makes it his goal to find out her scam before the lottery has the opportunity to embarrass itself. There’s your “U” in GSU. One week to prove she’s a cheater.

If the script has an Achilles heel, it might be Clark himself. The guy is super annoying. He’s such a stickler for the rules that you feel like if you ever had to spend five minutes with the man, you’d shoot yourself in the face. I mean who likes sticklers? That quality is almost universally saved for the villain (think Ed Rooney in Ferris Bueller’s Day Off).

So what do they do to cancel our hatred out and actually make us root for the guy? They start by giving Clark a daughter who he loves more than anything. It’s hard to dislike dads who will do anything for their daughters. I mean Clark is willing to give up every penny he has to send his talented daughter to the best music school in the country. Audiences absolutely LOVE selfless people. They love people who help others. And they love dads who put their kids first.

The writers also create a villain who’s way more of an asshole than the hero is annoying. The step-dad here tells Clark he’ll pay for Megan (the daughter) to go to the elite school, but only if Clark gives him full custody. He also regularly reminds Clark how pathetic he is and how far he’s fallen. Kind of makes you forget about the whole stickler issue.

I’ve seen the “make your hero more likable by making the bad guy more hateable” approach used to great effect. They actually do it a lot in the reality show, Survivor.

I’ll notice, for example, that I don’t particularly like one of the contestants. But as soon as the show builds up a villain who bullies that contestant? I can’t root for that character enough. The show is so aware of this secret power that when their big villains get voted off the show, they use clever editing and selective scenes to create ANOTHER villain out of the remaining contestants, just so it builds up support for the remaining players.

Finally, if you want to study how character flaws work in screenplays, find this script and read it. “Septillion” puts heavy emphasis on Clark’s obsession with the rules (his flaw). That’s what he needs to overcome to grow as a person. (spoilers) So the end of the script puts him in a position where he can either continue to follow the rules (and in the process screw over Joy) or loosen up (let Joy get away with it). It’s a little heavy-handed and on-the-nose but it’s this over-the-top quality that helps you see how arcing works. A great character arc is yet another script hack you can use to increase the odds of winning the spec lottery.

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Child custody is one of the most effective emotional plotlines you can add to your screenplay. If you create a situation where your main character doesn’t have primary child custody, and over the course of the screenplay make it more and more likely that he’ll lose custody, that’s almost guaranteed to pull a reader in. No one wants to see a parent who loves their child lose that child. So know that this subplot can be used to great effect to emotionally manipulate and pull a reader in.