Remember, the two goals here are to tell us your favorite script from the bunch, and to share your thoughts about the scripts so as to help the writers improve. Now get to it!

Title: The Peak of Fear

Genre: Horror

Logline: A documentary producer’s search for the cause of her father’s suicide leads her to a remote mountain weather station. A horrifying truth is revealed when she and her team are stranded by natural , and supernatural forces seeking revenge. Based on True Events.

Why You Should Read: As an adventure documentary filmmaker I’ve been in numerous places where I found myself saying – “This would be a great setting for a film”. A few years back I did a film on Mount Washington. More people have died there than on Everest. Having spent 3 nights up there in the desolate Weather Observatory, trapped by the elements, I can assure you that the place is a cosmic focal point of bad karma. “The Peak of Fear” is based on a true story which makes it even more terrifying. It’s full of “dramatic irony”, “flawed characters”, “mystery boxes” and “realistic dialogue”. Think “The Ring” meets “Cliffhanger” with a dash of “Mama”.

Title: Extradition

Genre: Action/Thriller

Logline: When a guilt-ridden husband tracks his wife’s killer to Cambodia, a non-extradition country, he must negotiate a strange land, its uncooperative police force and a ruthless gang to bring him to justice.

Why You Should Read: Ask any cop why they chose the profession, they’ll tell you the same thing – “to help people.” Ask us for the truth, and we’ll tell you about the first time we watched Martin Riggs, John McClane or Johnny Utah take down a bad guy. — Extradition is my humble attempt at inspiring the next generation of crime fighters, and was inspired by a conversation with a fugitive that detained on a traffic stop, only to have to release upon learning his warrant was non-extradition.

Title: CRYO

Genre: Sci-fi/Adventure.

Logline: The survivors of a horrific crash find shelter in an abandoned fortress only to discover a young woman who has been cryogenically frozen for a hundred years (A futuristic re-imagining of Sleep Beauty).

Why You Should Read: I’ve been writing for years and had some limited success by placing in competitions (like the semis of Nicholls etc) and had lots of feedback from query emails (for example I’ve had BenderSpink request to read my scripts two or three times) but I’ve never gotten any further than that. Perhaps my ideas/loglines are intriguing but the actual script and/or my style of writing doesn’t reel them in.

I feel like I’ve lost a lot of momentum recently and I just wanted to try a different approach. Cryo is a script of mine that I never really knew what to do with because it started out as an experiment. Most of my scripts have ended up in the 110 page range so I decided to write a script that would be a lean, mean 90 pages. A script readers dream.

As anyone will tell you writing a ‘dead on’ 90 page script is extremely easy to do, but extremely hard to get right. A producer once told me “A complete feature script that is dead on 90 pages either means the writer is a very talented or very inexperienced”.

I had initially envisioned Cryo as being the first part in an interconnected set of films which would re-imagine popular fairy tales in a sci-fi setting. Of course this was before every spec script started to sell itself as a ‘Marvel cinematic universe’ style starter.

A first for Scriptshadow. I thought it’d be helpful for you guys to see some real industry coverage (from William Morris Endeavor)!

Title: The Almighty Stud

Genre: Comedy

Logline: A flunking seminary student is chosen by God (and bestowed with a celestial superhero outfit) to seduce a reclusive female pop star and foil her plan to destroy the balance between the sexes.

Why You Should Read: The Almighty Stud was recently submitted to WME and the reader had very complimentary things to say, such as, “The biggest strength of The Almighty Stud is its great comedic timing along with an original storyline.” The screenplay was rated as GOOD and CONSIDER. I’ve attached the coverage in case you want to peruse it.

Coverage: WME Coverage Link

And finally, I mean, how am I going to pass up someone who includes a Scriptshadow rap in his “Why You Should Read?”

Title: JoePudder72’s Merry eMas

Genre: Comedy

Logline: The manager of a failing mall secretly conspires to holiday shop using his nemesis – the world’s biggest eRetailer, but when his mobile device is stolen, things get complicated (JINGLE ALL THE WAY meets FALLING DOWN).

Why You Should Read: I’m a writer from Vancouver BC, trying to get credit on a film that doesn’t include in its production contract “producer will provide pizza” with the amendment “two toppings only.” Sadly, I’ve signed a document with just such a clause.

My script would be natural to review on Friday November 28, better known as Black Friday (the warm up for cyber Monday). I think you should consider doing so, because I wrote you and the SS community a little poem.

REEVES RAP

He’s a screenplay talent scout,

His “Bada Bing!” is In-N-Out,

Got his own story currency –

Goals, stakes, mad urgency,

Plots that make him dance with glee,

Have reveals, twists, an amputee,

These things a scribe should learn to heed,

To avoid the dreaded – “what the Hell did I just read?”

And get a script that’s good to go,

Props from posters like Kay and Poe,

But you know your work is at its best,

If it gets the nod from Miss SS,

I tell ya dude this ain’t no scam,

Time to get with the PROGRAM,

As in – DISCIPLE Bitch!

Now I gotta kill this rhyme,

The end is now – it’s bullet time

Get Your Script Reviewed On Scriptshadow!: To submit your script for an Amateur Review, send in a PDF of your script, along with the title, genre, logline, and finally, something interesting about yourself and/or your script that you’d like us to post along with the script if reviewed. Use my submission address please: Carsonreeves3@gmail.com. Remember that your script will be posted. If you’re nervous about the effects of a bad review, feel free to use an alias name and/or title. It’s a good idea to resubmit every couple of weeks so your submission stays near the top.

Genre: Psychological Thriller

Premise (from writer): A young widow discovers her husband’s accidental death is the latest in a series of murders-for-profit reaching back more than a decade.

Why You Should Read (from writer): This is based on my published novel. In its review, Mystery Scene magazine described the book as “a story Hitchcock would have approved of.” Exactly what I was striving for.

Writer: John Joseph Moran

Details: 118 pages

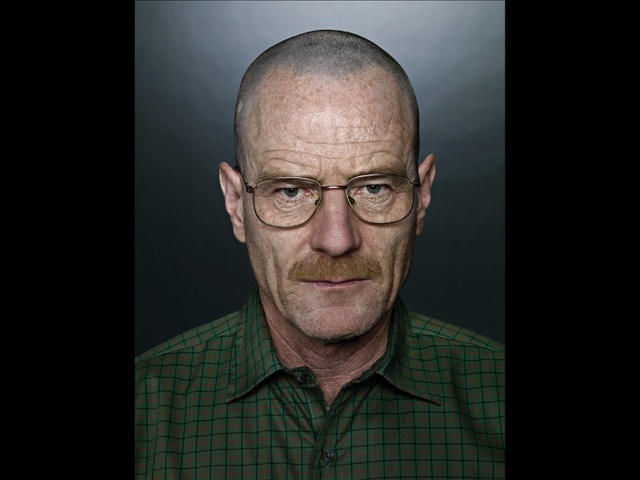

Christoph Waltz for Seifer? No-brainer.

Christoph Waltz for Seifer? No-brainer.

Scripts that start out fun always seem to have an advantage over ones that don’t. It takes more effort to get into those moody reads and even when you do, they never quite read as fast as the fun ones. I’m not saying you should never write a drama, of course. But in the competitive world of spec writing where every variable counts, picking up something that moves quickly sure makes things easier.

And that’s the experience I had with The Benefactor. Even at 117 pages, it never really slowed down. But why do I still have a case of the reluctants when thinking about it? Something about it feels… how do I put it? Light. There’s a level of sophistication missing, which left my suspension of disbelief in constant flux. The Benefactor destroyed the Amateur Offerings competition two Saturdays ago so I know a lot of you read it. Maybe, then, you can help me figure out why I felt this way.

When 35 year-old Claire Medina’s husband is hit and killed by a car, it’s bittersweet. On the one hand, he was her husband and father to her daughter. On the other, he was abusive and an altogether terrible person. As much as Claire hates to admit it, there’s a freeing feeling to her husband being out of her life. It’s almost too good to be true.

It turns out that’s exactly the case. A month later, Claire is approached by the sinister Nikolas Seifer, who informs her that he runs a unique business. He finds troubling individuals, individuals that spouses or family members wouldn’t mind dead, and he kills them in what looks to be an unfortunate “accident.” Afterwards, he approaches the spouse and asks for half of their fortune as payment for improving their lives.

Half Claire’s fortune is a lot of money. So Claire tries to find something on Seifer to use against him. But this guy is clever. He’s implicated Claire for the murder of her husband in several ways in case she doesn’t pay up.

Eventually, Claire realizes the best option is to give Seifer the cash and be done with it. So that’s what she does. But 18 months later (yes, you read that right – we have an 18 month time jump), Seifer appears again and tells Claire that to complete the loop, she has to kill someone for Seifer, his next mark.

Claire decides to turn the tables though, encouraging her mark, Fanning, to fake his death in order to take down Seifer. As her and Fanning wait for their plan to take shape, they fall for one another. But just as they believe they’ve cornered Seifer, he turns the tables back on them, and Claire finds herself fighting for her life, as she’s implicated for the murder of Fanning’s wife, a murder she didn’t commit.

This was a wild one. Lots of twists and turns here. The danger with a lot of twists and turns though, is that unless you’re extremely diligent, you’re bound to create some plot holes. There were a good half-a-dozen times here where I stopped and went, “Waaaait a minute. Couldn’t they just…?”

Like Seifer’s system. It’s a clever premise, don’t get me wrong. A hitman predicts that you want your spouse dead and therefore does it for you, only asking for the money afterwards so there’s no way for you to get caught. The catch is, he extorts you for the money.

But why only target “bad” people in this scheme? Since he’s extorting the people for money afterwards either way, can’t he technically do this to anyone, bad or good? What’s the advantage of only targeting bad people? I suppose it’s a little easier to deal with someone who kinda likes the fact that their asshole husband is dead. But nobody’s going to be thrilled when you demand half their fortune for the hit, whether they hated their hubby or not.

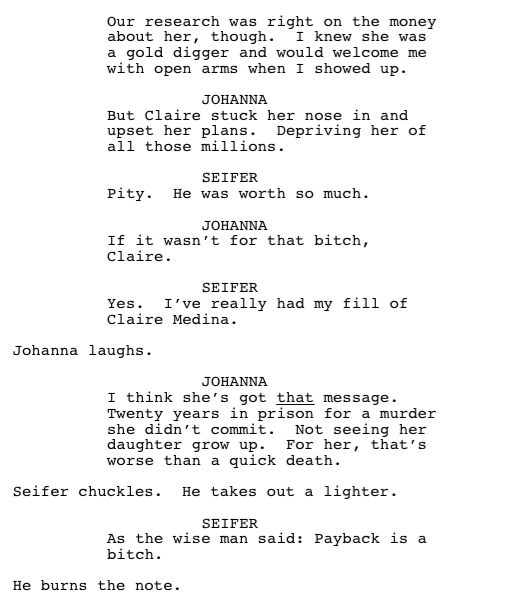

That’s what’s so frustrating about this script. It kept me reading all the way through. I wanted to find out what happened in the end. Yet it was littered with these lazy story pockets that weren’t believable for some reason or another. And again, it went back to a lack of sophistication. Let me show you a snippet of dialogue. Here, Seifer and his cohort, Johanna, are discussing how Fanning’s wife turned on Claire and their plan, allowing Seifer to gain the upper hand against them.

This is so over-the-top and on-the-nose, you can practically hear the sound of Seifer twirling his mustache, with Johanna “MUWHAHAHAING” in the background.

You may also notice the “explainy” nature of the dialogue (“Twenty years in prison for a murder she didn’t commit…”). There is a TON of this throughout the script. “Why can’t we go to the police?” “Because if Character A tells Character B we went to the police then it’ll mean we’re screwed. But if we follow Option C instead, then…”

Explainy dialogue almost always means the writer is using his characters to talk to the reader instead of his characters talking to each other. This is why this dialogue feels stilted and artificial, because it’s being directed at the wrong person. Dialogue must always, first and foremost, sound like two characters talking to each other. As soon as one of them stands up on their “explanation soapbox” to address the reader directly, you’ve pierced the reader’s suspension of disbelief.

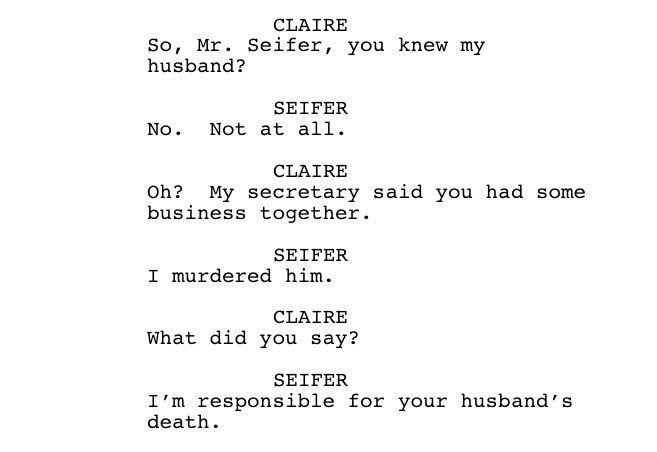

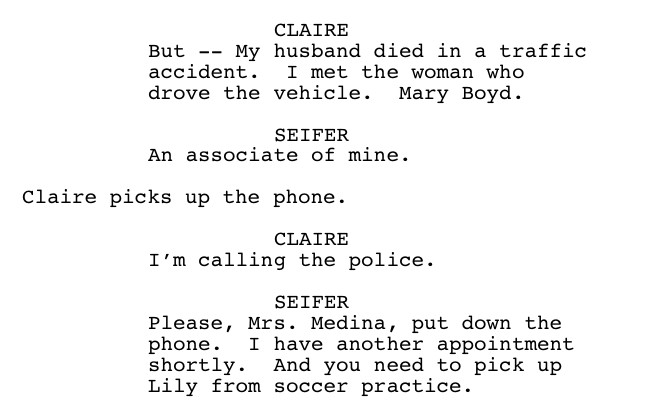

And that problem was persistent throughout much of the screenplay. Too much of the dialogue felt “off” for one reason or another. Take this exchange early in the script. Four weeks after her husband’s death, Claire is sitting in her office when Seifer arrives. Here’s the exchange.

While I don’t think this is terrible dialogue, it rang false (to me, at least). If someone says to you, “I murdered your husband,” are you really going to respond with, “But – My husband died in a traffic accident. I met the woman who drove the vehicle. Mary Boyd.” Someone just told you they are a murderer and you’re responding with a conversational rebuttal?

I could see freaking out. I could see realizing you’re in danger and enacting some sort of stall tactic while you figure out what to do. At the very least, note Claire freezing when she hears these chilling words. But without clarification, it reads like the ho-hum response of someone who’s just been accused of leaving the iron on. It’s emblematic of issues I had with the dialogue throughout.

The other big problem here has to do with time. Remember that unless you’re doing a period piece, you want the time frame for you movie to be as contained as possible. Any big time jumps mean a loss of momentum. But they also mean a lack of planning. It’s indicative of a writer who hasn’t worked hard enough to keep his story moving in one continuous timeline.

I mean the 18 month time jump is nothing short of a momentum assassination. If there’s any way to eliminate it, I’d do it. And then there’s Claire going to jail and the subsequent courtroom trial, which is another huge time jump. You have yourself a thriller here. You don’t want to end up in a boring courtroom drama sequence. Case in point. Imagine if Silence of the Lambs ended in a courtroom case. Do you think it’d still be considered a classic?

As soon As Claire goes to jail, get her out on bond, and have her and Fanning find and confront Seifert. It makes no sense to have your main character sitting in jail while this Fanning character, who we met less than 30 pages ago, searches for our villain.

Speaking of Fanning, I thought for sure he was going to turn out bad. I thought the whole idea behind Seifer’s system was that he targeted evil people. With Claire disrupting the system, I believed the irony would be that she’d pay the price. Fanning would end up doing something horrible to her. But even if you don’t explore that avenue, it seemed weird that all these people Seifer had killed previously were terrible human beings, yet Fanning turned out to be a great guy.

Anyway, I think Moran deserves some props for coming up with a unique premise and an unpredictable story that moves from start to finish. But to get this up to “worth the read” territory or higher, he needs to shore up some of the dialogue issues. I mean this is a “Hitchcock-like” story and I don’t remember a single conversation that included dramatic irony. Watch Psycho and note how nearly every dialogue scene contains dramatic irony (one character is lying to another). Fix that and the excessive time jumps and The Benefactor is going to be the real deal.

Script link: The Benefactor

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me (just missed a ‘worth the read’)

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Beware of characters being too “explainy” (“Why can’t we go to the police?” “Because a) it means blah blah, b) that would entail blah blah blah, and c) the villain would blah blah us”). Either cut all this explaining out or look for other ways to convey the message. For example: “Why can’t we go to the police?” Claire pulls out a newspaper with the headline, “Man Found Dead in Car.” “This is the last guy who tried to go to the police.”

What is the second act? When does it begin? When does it end? I started asking myself these questions after watching this writers roundtable the other day (thank you, commenter who posted this). John Favreau brings up a great point about how the second act is a series of lessons for your main character, and that’s something I’ll get to later on. But just the topic of the second act in general intrigued me, because I think no matter how much you dissect it, the second act is still full of mysteries. It’s like this cave where, every time you think you’ve found the end, there’s another little tunnel that extends even deeper.

Before you can figure anything out about this elusive act, though, you have to know where it begins and where it ends. It begins when your character goes on his journey to pursue his goal. So for those of you who saw Interstellar, that would’ve been when Coop blasts off in his ship on his JOURNEY to find new planets that will save mankind.

The end of the second act is a little trickier to locate. A lot of people will say that it’s when your character is at his lowest point. But I don’t think that’s helpful. It doesn’t give you a concrete destination to take your character. A better definition is probably: when it APPEARS that your main character has FAILED at his goal. Now Interstellar had a whole lot of shit going on, so it’s not the easiest script to decipher when this happened, but I’d probably say the end of the second act is (spoiler) when Matt Damon nearly kills Coop. Either that or when Matt Damon destroys the orbiting ship. In The Hangover, it’d be when they think they’ve found Doug, only to realize it’s not “their” Doug. Time is up. There’s nowhere else to look. They’ve failed at their goal.

Preferably, this “start goal/finish goal” is how you’d approach all your second acts. But as we all know, not every story is this “clean.” Sometimes, the character goal will shift to something else in the middle of the movie (in Aliens, the goal is to go in there and kill the aliens. But when that goes bad, it becomes more about escaping). In other cases, the goal isn’t concrete (American Beauty). And in some movies, there isn’t a goal driving the story at all (When Harry Met Sally). Now I’m not saying that every screenplay has to be goal-oriented, but I will say that the further you move away from that model, the trickier the second act gets. And when you’re talking about something that’s tricky ANYWAY, you can see why so many scripts die here.

To be honest, I wish someone would write a book and just definitively declare the death of the 3-Act structure and make it 4 acts instead. That way you’d have 4 evenly divided sections, making it so much easier to get a handle on your story. In the 4-act scenario, the second act would be the “wind-up” act, where mysteries are being set up and the hero is getting a feel for just how bad the situation is. And the 3rd act would be when the shit really hits the fan. When the big-daddy obstacles are thrown at your hero and when success really starts to come into doubt. The 4th act would then be the rebirth, regroup and charge-in act. To me that’s a lot easier to get my head around.

But even if you have all that stuff in order, there are still certain things you gotta hit in the second act. Obstacles, for example. You want to throw things in the way of your hero so that nothing they do is easy. And remember, it’s hard to throw obstacles at your hero if they don’t have a goal they’re pursuing. Because if there’s no goal, then how do you place something in the way of that goal?

Now here’s where we get to what Favreau was talking about. As much focus is put on properly plotting the second act, the second act is really about character, and more specifically, TESTING YOUR HERO. Let me repeat that. The second act should put your hero through a SERIES OF TESTS. If you’re not testing your hero, you’re not developing your character. And the development of your character is the key to creating an emotional connection with the audience.

To achieve this, you first have to know what your main character’s flaw is. What is it that’s keeping them from being happy, keeping them from being “whole?” This is something your hero may not even be aware of. So for Gravity, Sandra Bullock’s character’s flaw was that she’d given up on life. She’d packed it in. This way, every obstacle that arrived onscreen wasn’t just an excuse to create a fun special effects shot. It was a test of her resolve. To see if she would fight to live or to give in. So the one-two punch of finding a flaw, and then repeatedly testing that flaw, is one that really packs an emotional wallop into the second act, and what builds the bridge for you to care so much in that final act, when the final test arrives.

In addition to this, the second act is about keeping things fresh. Most of the bad second acts I read – and I read a lot – make one critical mistake. They keep giving you the same thing. For example, I recently read a romantic comedy where the main character was pursuing a girl. The second act consisted of scene after scene of him trying to win over this girl. They were all the same scenes. Sure, the locations were different, but the make-up of each of these scenes was the same.

You solve this by BUILDING your second act. And to properly build, you need to do two things. Each major plot point must feel bigger than the previous one. And each major plot point must have HIGHER STAKES than the previous one. There will be some ebb and flow in the valleys between the major plot points. But the plot points themselves must feel bigger as they go on. Early in the second act of Star Wars, Luke and Obi-Wan need to find a pilot. The stakes are pretty high cause of this R2-D2 fellow. Later in the second act, they’re trying to escape from the Death Star with the Princess. A bigger plot point with higher stakes.

But just building isn’t enough. The second act is such a huge chasm of never-ending space that you have to surprise your audience every once in awhile, or else they get bored. You can do this with a surprising mid-point twist (in Gone Girl – spoiler – this is when we find out that Amy has been conning Nick), you can have your hero unexpectedly achieve his goal (he finds the killer!) only to announce a new goal soon after (it turns out they were after the wrong guy all along – the real killer’s still out there!). Or just throw in a fun surprise or three, something the audience isn’t expecting.

Keep in mind that it’s really hard to do any of this without a plan in place. And this is where you usually see the difference between amateurs and pros. Amateurs will try and wing the second act. They’ll try to come up with all these things on the fly, not realizing just how long the act is, usually resulting in them running out of steam (almost always around page 50).

Pros know that the second act is like a 100 day hike up the Pacific Coast Trail. If they don’t chart how much food and water they need, when they’re going to reach re-supply stations, or forget crucial tools they need to survive, they’re probably going to die. So as much as some of you hate to hear this, one of the biggest keys to surviving the second act is outlining. It’s a portion of the script that’s screaming out for a plan. And while I’m not saying you non-outliners can’t be one of the lucky ones who emerges at the finish line unscathed, it’s a lot more likely that you’ll die a drawn out agonizing death. ☺

I’d love to hear your own experiences with second acts and what helps you guys get through them. The more we can help each other out, the better we all get.

Genre: Drama/Adventure

Premise: The heretofore unknown tale of Pinocchio’s famous father, Geppetto.

About: Michael Vukadinovich’s script hit the spec market in 2011 and was snatched up immediately by 20th Century Fox for mid six figures. Vukadinovich began his career as a playwright (his most celebrated work being, “Trog and Clay (An Imagined History of the Electric Chair)” before moving into screenwriting. He has another project with Peter Dinklage attached called, “Rememory” about a professor who can record memories. The Three Misfortunes of Geppetto was a 2011 Black List script. Shawn Levy, the director of the Night at the Museum movies and, more recently, “This is Where I Leave You,” is attached to direct.

Writer: Michael Vukadinovich

Details: 118 pages

I decided to review this script today for one reason. To highlight the most spec-sale friendly of all the types of scripts out there.

There is no other type of script that has done better in the market over the last ten years. The formula? You find a fairy tale, then find a new angle to tell the story from. Whether it be the recent Malificent, about one of the most famous fairy tale villains in history, the edgy take on Snow White that was Snow White and the Huntsman, the dark spec sale from a couple of years ago, “Pan,” that reimagines Peter Pan as a serial killer. I’ve read 20 other spec sales in the past five years that have also succeeded with this formula. Hollywood goes nuts over this stuff.

And it’s not hard to imagine why. When a studio looks at a project, the first thing they do is ask how it can be marketed. Will the marketing be easy or difficult? The more difficult it is, the more stellar the other components of the screenplay have to be. But usually, there’s a tipping point – and it’s not very far down the line – where if the marketing is too tricky, they don’t bite.

With these kinds of screenplays, the marketing is always done for you. You say, “Snow White” and people immediately know who that is. There’s a comfort level there, like having your favorite coffee in the morning or turning on your favorite sit-com after a long day of work. So studios are always all over these scripts. In addition to Shakespeare adaptations, they’re one of the most bankable script approaches out there.

The Three Misfortunes of Geppetto places us squarely in the year 1919 where we meet Geppetto, an optimistic enthusiastic young man with his whole life ahead of him. But Geppetto can only think of one thing – the beautiful Julia Moon. Their love for one another is so powerful, you get the sense they fell in love BEFORE first sight.

The two know they’re spending the rest of their lives together, but before that can happen, the Depression hits and Geppetto’s family loses everything. This is when we first meet Geppetto’s evil nemesis, Edmund Vile (pronounced “Vee-lay!” he tells everyone). Edmund hates Geppetto and his perfect life and will do anything to destroy it. He starts by trapping Geppetto’s parents on a train crossing, watching gleefully as the train hits and kills them.

When Geppetto is later sent off to the war, he hears that Edmund has moved in on Julia. She refuses to marry him, but when word comes back, erroneously, that Geppetto has died, she has no choice. When Geppetto finds this out, it’s a race to get back in time to stop the wedding and be with Julia once more.

(spoilers) Geppetto succeeds in the knick of time, and ends up marrying Julia. But then Edmund has a witch put a spell on the two, making it impossible for them to have children. The couple will have to come up with another solution, a solution I’m pretty sure you can figure out. But the evil Edmund will do his best to stop it, in a last ditch attempt to destroy the couple’s life forever.

Jiminy makes a cameo in the script!

Jiminy makes a cameo in the script!

So let’s see if we can do this here. Pick a well-known fairy tale that’s in the public domain. Let’s say… Beauty and the Beast. Now look for a new angle to tell the story from. We could set the story in modern times? That could make it fresh. We could make the girl the “beast” instead of the guy. Role-reversal usually works. Or maybe we tell the story on a planet inhabited by beasts, and the girl is the only “human” and therefore a “beast” to them.

I’m only half-joking with these ideas. Obviously, I’m making this sound a little easier than it is, but I bet if you spent an entire week trying to come up with a fun fresh take on a fairy tale, you could. Of course, the second ingredient to this meal is that you have to love these kinds of stories. If you’re writing strictly for cash, the reader can tell. That’s what’s allowed “Geppetto” to stand above its competition. You can tell Vukadinovich loves his subject matter.

I’m not sure I’ve ever read something so unapologetically saccharine. “Geppetto” wears its heart on its XXL sleeves, pumping its sugar-laced blood directly into the reader’s veins for good measure. Geppetto, with his idealistic world view and his stay-positive attitude despite one tragedy after another makes it impossible to root against him.

Indeed, we talk about making characters likable all the time. One of the easiest ways to do so is to bestow tragedy upon tragedy on your character. We see that here, with his parents dying, with Geppetto and Julia not being able to have kids. Poor Geppetto even has to watch a baby whale die!

But what if you want to take your character from likable to lovable? Spiking the likable punch requires never having your hero sulk about his misfortunes. Have him stay positive and keep fighting. No character is more likable than the one who stares adversity in the eyes and keeps on fighting. Think about it. Who are the people in life you most admire? Chances are they’re people who keep fighting no matter how bad it gets.

Where Geppetto stumbles is in its structure. It sets up its story nicely. And then when Geppetto goes off to war, the story goal arrives – he must get back to Julia before she marries Edmund. (spoiler) But that goal is achieved on page 75. And there are still 45 pages to go. “Geppetto” decides not to replace this goal with a new one.

Instead, the goal is shifted over to Edmund – His goal becomes to ruin Geppetto’s and Julia’s happiness. You can probably hear me groaning. I don’t like non-specific goals. They don’t have that clean understandable objective that the audience can get behind. I can understand stopping a wedding. Destroying one’s happiness is too vague. And it shifts the goal away from the main character, which is always a dangerous thing to do, especially as you’re entering your last act, when, preferably, you want your hero to be his most active (if he has no goal to pursue, then by definition he’s not going to be active).

So that really hurt the script, and it’s something I’m sure the studio has been trying to address in the rewrites. Another problem is that “Geppetto” loves its influences a little too much, those influences being Forrest Gump, The Princess Bride, It’s a Wonderful Life, and Amelie. True love is mentioned numerous times here. We also start in the present with a grandfatherly character telling his grandson this tale. We have fun little flashbacks, a la Forrest Gump, of great grandfathers, great great grandfathers, and great great great grandfathers, dying of heart attacks. And Edmund seems almost beat for beat, a Mr. Potter clone. Sometimes reading Geppetto was like driving down memory lane for your favorite movies.

Despite that, the script has such an earnest idealistic love for its story, and Geppetto is so darn likable, that the script survives this and the structure problem. It’s an unexpectedly sweet tale that is sure to give you goosebumps at least a couple of times. And, for the most part, the proper way to approach this kind of script.

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Remember that when you shift the goal that’s driving your story over to your villain, you are making your main character inactive or reactive. Since audiences tend to like characters who are active (who drive the story), this is a dangerous route to take. However, if you do it, I’d advise doing it in the first half of your screenplay as opposed to the second. The second half is where you want your hero the MOST active. For example, in Star Wars, the movie starts off with the villain having the goal (Darth Vader is trying to get a hold of the Death Star plans). But in the end, Luke has the goal that’s driving the story (to destroy the Death Star).

Genre: Drama

Premise: When a retired criminal gets back in the drug game, he starts taking out the organization’s dead weight, having no idea that one of his targets is his son.

About: Bill Kennedy has been steadily moving up the ladder, having recently penned the weird but kinda-funny Haley Joel Osmet comedy, Sex Ed. He’s also one of the bigger writers on the series, House of Cards (he’s written 8 episodes), and recently adapted “Cyber Storm” for Fox. That project is about a massive snow storm that cuts New York off from the rest of the world (and, of course, chaos ensues). This script, The Fixer, finished with 7 votes on the latest Black List.

Writer: Bill Kennedy

Details: 115 pages (4/9/13 draft)

Anybody here hear of Charles Bukowski? He’s a semi-famous American writer who wrote some pretty great books in the 60s and 70s. He was also strongly opinionated. He thought a whole lot of other writers sucked. In fact, it was rare that Bukowski came across anything that he liked.

Now you have to remember, Bukowski lived back in a time before Amazon and Goodreads. Outside of recommendations from the New York Times, the only way to find out if a book was any good was to actually read it. The insanity, right? So Bukowski used to sit in the library and open book after book, reading as many pages as he could muster, before throwing them down and moving on to the next one. “Why doesn’t anybody SAY something?” he would ask. “Why doesn’t anybody SCREAM OUT?” he wanted to know.

He hated so many of the books he opened, he started to wonder if there was any good writing anymore. Then he came across a book called “Ask The Dust” by John Fante. “The lines flowed easily across the page,” he said. “Each line had its own energy and was followed by another like it. The very substance of each line gave the page a form, a feeling of something carved into it. And here, at last, was a man who was not afraid of emotion. The humor and the pain were intermixed with a superb simplicity. The beginning of that book was a wild and enormous miracle to me.”

Wow! Talk about an endorsement. Isn’t this what we all hope for? To pick something up and be so taken away that the very foundation of our being is shaken?

I bet you’re wondering right now, is The Fixer the next great script? The next Desperate Hours or Nightcrawler? Had I found something with the kind of passion and power to make me stand on the metaphoric mountain tops and demand the world read it, like had happened with Bukowski and Ask the Dust?

In a word, no.

But, I will say this. I read the first five pages of seven professional scripts before I read The Fixer and The Fixer was the only one that attempted to grab me. It was the only script that seemed to WANT me to read it – reminding me of Bukowski’s experience. The first scene finishes with this voice over line: “I’d kill the cockfuck if I could. But I can’t, and I need money to run away, to start over. So I’m going to have to kill these guys, who happen to be friends of mine.” A few pages later, a criminal is so mad that McDonald’s won’t serve his son a Happy Meal because it’s before 10:30 AM, he puts a gun to the checker’s head and tells him, “Get me a motherfucking happy meal.”

This is a script that wants to be read.

I’ve said this before. While not every story is meant to be told this way, most scripts need an edge to stand out. This script had a big ole heaping of edge. BUT. Grabbing someone’s attention and keeping someone’s attention are two different things. The Fixer grabbed me. I prayed it wouldn’t let me go.

50-something Joe is a Fixer. I must admit, I’m not clear on what that is. But according to the few clues we get, it means Joe matches business people together, and then takes a cut of their business. Joe has been out of the game for awhile but he’s going stir-crazy at home. His wife is battling severe depression and rarely leaves the bedroom. Joe wants back in the game.

A friend sets him up with a local drug dealer, Terrance (the guy I mentioned earlier who demanded a Happy Meal), and Joe starts helping him get rid of the dead weight in his business. Joe finds out pretty quickly when he looks into the books that someone is shorting Terrance, and the two start trying to figure out who it is.

Meanwhile, we meet Nick. Nick is Joe’s son, a perennial screw-up. Nick’s harboring a secret from his father – that he’s gay, which keeps him from telling his dad anything that’s going on in his life. Nick gets a job offer to start selling drugs. This is his chance to finally make some money, to show his father that he’s worth something, so he takes it. The problem is, his deadbeat boyfriend, Mark, keeps injecting just as much as he’s selling. Naturally, this leaves him short come pay-up time.

As you might have guessed, Nick is working for Terrance, which means Nick is unknowingly working for his father. And when his father unknowingly pinpoints him as the dealer who’s shorting Terrance, Nick is given less than a week to find the money or die. Will Joe figure out he ordered his own son’s killing before the trigger is pulled? Gosh-darnit I hope so.

The Fixer has a pretty nice premise. You have some nice irony here. A man who unknowingly orders a hit on his son. And Kennedy’s put a lot of work into the character stuff in general. This is what good screenwriters do – every single character has something going on. They’re not paper characters. They’re real people with real problems.

Joe’s wife has severe depression and stays home all day, slowly sucking all of Joe’s life away in the process. Nick is secretly gay and terrified to tell his father. Terrance is still in love with his son’s mother, but she won’t give him the time of day. He’s running this business so he can woo her back with a good life.

Despite this, there were other parts of Joe’s character that were bothering me. Although he clearly starts as our main character, he kind of gets moved to the background. He only seemed to pop up to keep Terrance in check every so often. When you introduce someone as the captain of your ship, we expect to see them at the wheel. Joe wasn’t at the wheel very much.

I started to wonder why Kennedy was doing this. And then I realized, Joe is the only character here who doesn’t have anything at stake. Nick is 5 figures in the hole and needs to find the money to save his life. Terrance needs this business to get the love of his life back. But why did Joe need this? If this all falls apart, he goes right back to his previous life and, presumably, could go ahead and hook up with another drug dealer and start over again.

Also, Kennedy didn’t make it clear enough what a “Fixer” was. We’re told, in Joe’s own words, that a Fixer is someone who brings two business people together and gets a cut of their business. But then Joe goes and leads a drug operation. Does this also fall under the definition of “Fixer” as well? Or is he doing this independent of his old job?

A writer can never forget that while something may be obvious to them, they are not the audience for their scripts. Most of the audience won’t know the details of their world. Therefore, it’s up to the writer to explain them and make them clear. I didn’t get that here.

Finally, I didn’t get the sense that Kennedy really knew this world. He knew more than most. But as far as the specifics of how a drug operation was run, a lot of stuff felt muddy. Here’s something to remember. When you’re writing any kind of criminal movie, your bar has to be Scorsese. One of the reasons his movies are so successful is because he leaves no doubt that he knows this world inside out. We get details on top of details on top of details about how the drug trade works, the casino trade works, the financial trade works. That’s the kind of specificity you have to bring to the table because if you don’t, the script always feels lacking in a way the audience can’t quite put their finger on.

How do you achieve this kind of realism? You may not be able to physically go into the drug trade to do research (although I’d be impressed by any writer so dedicated as to do this). But you can still watch documentaries, read nonfiction books, go to message boards that have real people who do this kind of shit to talk to. I just always feel a little cheated when the subject matter I’m reading about feels fudged.

The Fixer started off with a bang, and was pretty good in places. But in the end, it didn’t quite keep my attention.

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: To understand if your character has the appropriate level of stakes attached to his character, you simply ask, “If this character fails, what do they lose?” For Joe, if this drug operation fails, he goes right back to where he was at the beginning, where the worst problem he was dealing with was that he was bored. I don’t think those stakes are high enough. (I suppose you can make the argument that the stakes are his son’s life, but not only does that development come late in the script, but those stakes feel indirect, since he has no clue that his son’s life is even in danger. – This brings up an interesting question – does one need to be aware of one’s stakes for them to work?)