Genre: Sci-fi

Premise: In the future, 99% of the human race has been eliminated due to a virus outbreak. One of the survivors is sent back in time to try and kill the man who started it all.

About: This is college roommates’ Terry Matalas and Travis Fickett’s first series, although the two have worked before in TV on such shows as “Terra Nova” and the CW’s “Nikita.” Fickett is pretty excited to have the job, offering, “It’s constantly surreal. I’m still not used to writing something and almost the next day seeing a prop or piece of costuming or something just take shape.” Indeed, this is every writer’s dream! 12 Monkeys will premiere on SyFy this January. This is an earlier draft of the script, before showrunner Natalie Chaidez came on and added some finishing touches. For those who don’t know how a TV series works, the writer of the show will sometimes head up the showrunner position (where they’re actually running the show), but in cases where the writers are really green, or in situations where the writers don’t want the responsibility, they’ll hire a separate person to run the show, as was the case here.

Writers: Terry Matalas & Travis Fickett (inspired by the film written by David Peoples & Janet Peoples)

Details: March 2012 draft – 62 pages

Count me as a big fan of Terry Gilliam’s 1995 film, “12 Monkeys.” You remember those days, right? When studios took chances? And 12 Monkeys was one hell of a chance to take. It dirtied up its stars. It was “artsy.” It was different. It even gave you an ending that, gasp, made you THINK!

So I wouldn’t say I was against making the film into a TV series. But here’s my problem. In this new dash to fill up the hundreds of original TV spots that are out there, the TV folks are starting to do what the lazy film folks have been doing: Look into the past. Find something that’s already proven, either in this medium or another, then translate it. I mean they’re making a TV show based on Limitless for God’s sakes. Limitless?? That’s not a TV show.

And then there’s Syfy. Syfy is this channel that has the potential to dominate the sci-fi landscape, to take this new television world that stresses quality, find some wild out-of-the-box ideas, and give them the A+ production treatment. Become the genre version of AMC. Instead, they’re making bad B-movies and cheesy shows like the cringe-worthy Walking Dead knock-off, Z Nation.

I’m going to hope that 12 Monkeys is part of a new company mandate to start offering quality material. Because if there was ever a project that had some actual weight behind it – something that you could really play with and sink your teeth into, this is that property.

Cole lives in a post-apocalyptic future. Weeds have grown up through the pavement. City buildings are falling apart due to lack of care. Technically, Cole is one of the “lucky” ones who survived the virus that killed 99% of the world, but it sure doesn’t feel that way. In this future, you can’t even breathe without the help of an oxygen mask.

So it sure is nice when Cole gets sent back to the past, like before this whole apocalypse thing happened. Cole’s looking for a woman named Cassie Reynolds, a cute doctor who, later in life, will inform Cole that he has to jump back into the past and find her. If that makes sense.

The reason Cole needs to find Cassie is because Cassie knows where the ominously named Mason Frost is. And Mason Frost is the one who creates the virus that kills everyone. I’m guessing Cole saw Terminator 2 growing up, and he assumes that if he kills Mason, he’ll save the world.

But first he’s got to convince Cassie that he’s actually from the future, as people of the year 2014 have a hard time accepting time-jumping at face value. Once he convinces her, the two go on a little quest to find Mason and (big spoilers!) when they do, Cole kills him. Except that when he gets back to the future, it’s still the same. Mason must not have been the key piece. Which puts Cole right back at square 1.

One of the things I found really cool about the original 12 Monkeys was that we weren’t sure whether Cole was crazy or not. The future could’ve all been in his mind. The past could’ve all been in his mind. Maybe he was just a guy sitting in a white padded room in a straight-jacket.

When they ditched that here, the pilot lost something for me. However, I did recognize the difficulty inherent in maintaining a question of sanity over an entire series. Time travel alone is tricky to wrangle, so I’m guessing they saw this other question as too complicated and turned a variable into a constant.

Was the constant any good? It’s hard to say. Sort of, maybe? I’ll tell you one choice that infuriated me though (spoilers). There are zombies in 12 Monkeys. It’s been many years since I’ve seen the Gilliam film but I’m fairly certain there were no zombies. Yeah, they don’t call them “zombies” here. But there are these semi-dead people with white eyes in the apocalyptic future who try to kill you.

Look, I don’t have a problem with adding zombies or vampires or werewolves to anything. What I have a problem with is when the monsters are shoe-horned into the story inorganically. Readers and viewers can tell when you’re hopping on a trend instead of building an honest mythology. And if it screams “cheat,” we’re going to call you on it. I mean there’s a chance this will all be explained later satisfactorily. But there wasn’t enough good in this pilot to imply that that would be the case.

Further lowering my confidence was the use of “Occam’s Razor” in the dialogue. I cannot tell you how many times I’ve read a character asking another character, “Have you heard of Occam’s Razor?” in a sci-fi script. Yes! We’ve heard of Occam’s Razor! In just about every single science-fiction screenplay written between the years of 1995-2005. It’s the sci-fi equivalent to the “Scorpion and the Frog” fable. These things need to be locked up in a writer’s “never to be used again” box.

I mean, come on. We’re writers here. One of the only things we have control over is effort. We might not be the most talented. We might not be the most educated. But we control how hard we try. And if you’re going with Occam’s Razor, one of the most often used example theories in the business, it says you’re not trying hard enough to come up with something original.

Another red flag here was the villain who was evil just because he’s a villain. Mason Frost is a nasty evil individual not because there was something in his past that made him this way. Not because of some psychological problem. But only because he’s the villain and it’s the villain’s job to be evil.

Characters in screenplays are supposed to be REAL. They’re supposed to have lived full lives, just like you and me. If you treat a character as if they are a simplistic cog in the machine, they will treat you that way right back. They will only give out what you put into them. And if all you think of them is that they’re “evil” then how do you think they’re going to represent themselves? In big general generic evil ways.

But if you figure out why your villain became this way. If you map out (either mentally or in a document) what brought them to this point in their lives, they’re going to give you a lot more. Because they have more to give back from. So yeah, that really frustrated me.

I mean the story for the 12 Monkeys pilot isn’t that bad. It’s kind of cool to see this disheveled guy from the future come back to this perfect world and try to kill this guy. It’s got a lot of the story elements that I champion here on the site. It’s got a goal. It’s got some of the biggest stakes you’re going to find. But everything else here felt too familiar. It didn’t feel like the writers were trying hard enough to give us something fresh. The zombies are a perfect example of that (“Hey, why not throw in zombies?” “Yeah, why not!”).

I will hope that the series proves me wrong but as for the pilot script, it wasn’t for me.

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: One of the many things you have to pull off in a TV pilot, is a “preview,” if you will, of what the show will be like going forward. By watching the first show, we should get a feel for what dozens of future episodes will look like. After 12 Monkeys was over, I didn’t see where we were going from here. (spoilers) He’d killed Mason, so he’d achieved his goal. Game over, right? Sure, when he gets to the future and learns that it’s still the apocalypse, we’re guessing he’s going to have to go back to the past again, but in what capacity? Are we just going to repeat this episode over and over again where he looks for “the next guy” to kill? I’m not getting a strong enough sense for what’s next. And when the audience doesn’t get that feel, they don’t tune in next week.

Newsletter is here!: Guys, the Newsletter is OUT! Check your SPAM and PROMOTIONS folders if you didn’t get it. A new horror spec reviewed with Apocalypse Now as its inspiration and a lot of other fun stuff. If you’re not on the Newsletter list, sign up here!

Genre: Sci-fi/Drama/Thriller

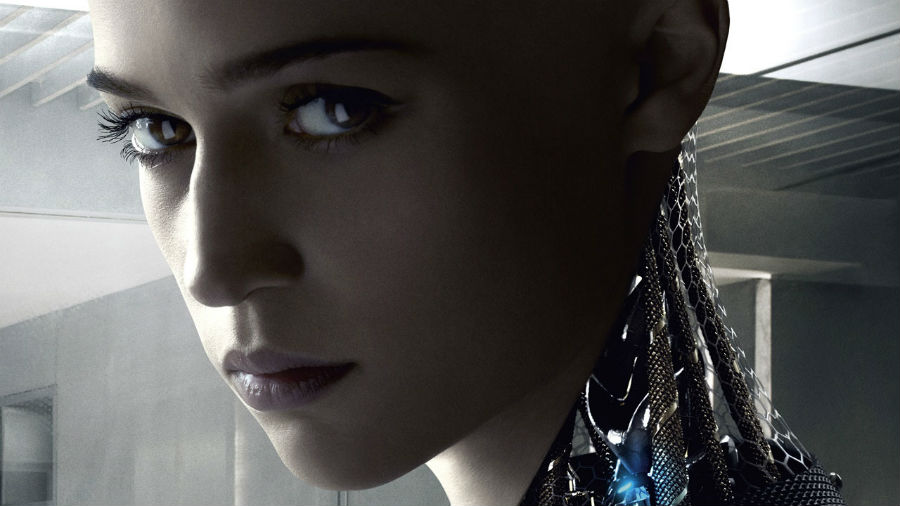

Premise: A billionaire programmer handpicks a young employee to spend a week at his remote estate and participate in a test involving his latest invention — an artificially intelligent female robot.

About: This will be the directorial debut of Alex Garland, who also wrote the script. Garland has been one of Danny Boyle’s right hand men, writing The Beach, 28 Days Later, and Sunshine. He penned the dark drama adaptation Never Let Me Go a few years ago, most recently scribbled the cult hit “Dredd,” and has also written drafts of Halo and Logan’s Run. In other words, he’s big time. This script sold last year. (Addition) This review originally appeared in the newsletter last year. Off of the cool trailer that debuted last week, I decided to post the review on the site.

Writer: Alex Garland

Details: 114 pages – undated – version “.08” (which leaves this draft legally over the limit)

Garland’s been hit or miss with me. He hit with 28 Days Later and Dredd but wrote two movies that utterly fell apart in their final acts in Sunshine and The Beach. I’d almost rather watch a bad movie from start to finish than watch one that starts well and then collapses. Then again, Boyle was guiding Garland along during those films, so maybe it was him who screwed them up.

I decided to read Ex Machina due to its “spec-friendly” nature. It’s a small character driven film hidden inside a sci-fi concept. The idea with any screenplay is to draw them in with the flashy premise, then make them stay with your characters.

Ex Machina introduces us to computer whiz Caleb, a young man who cares more about beating his personal 24 hour coding record than he does trolling the local Starbucks in hopes of convincing an artsy chick to give him her number. Caleb is currently coding a program that appears to be for a contest, a contest he’s desperately trying to win. And to his amazement, he does just that.

It’s only once we’re in a chauffer-driven limousine that we realize what this prize entails. Nathan Bateman, a young eccentric billionaire, has awarded Caleb one week at his home – to stay and hang out – though the exact reason for the stay hasn’t been revealed yet. As Caleb impatiently asks the chauffeur how long it will be until they get to the estate, the chauffeur calmly responds, “We’ve been driving through his estate for the past two hours.” Yes, Nathan is that kind of rich.

Nathan’s also kind of an asshole, and a douchebag, which we pick up on pretty quickly. He lives off in his own little Hearst Castle Wonderland, completely out of touch with reality. Of course, Nathan’s making so many amazing things happen, it doesn’t really matter. He believes he’s just created the first fully conscious artificially intelligent robot. That’s why Caleb’s been brought in, to test this creation. Which is how we meet Ava.

Ava is a beautiful piece of machinery that doesn’t look anything like a piece of machinery. She’s a flawless perfect stunning blonde woman who just happens to be made up of wires and circuit boards. But you wouldn’t know it by talking to her. She’s calm, clever, even funny. Caleb takes to her immediately. Maybe a little too much.

What follows is a series of tests that Caleb puts Ava through to determine if she’s just programmed to feel things or if she ACTUALLY feels things. For those of you who aren’t super-geeks who have read all the books on the Singularity, creating a robot that’s conscious of itself is basically the Holy Grail. And the more Caleb talks to Ava, the more convinced he is that Nathan has found this Holy Grail.

Ahh, if it were only that easy though. Things start to get messy. Caleb begins to suspect that Nathan is fucking with him. He just can’t figure out why or what about. He also begins to have feelings for Ava, something that would’ve sounded ridiculous at the start of all this, but now seems quite natural. He also learns that Ava hates her creator and would do anything to get away from him. Would Caleb…could Caleb perhaps…help her escape? They could even run off and be together. This becomes the plan as the story pushes towards its final act. That is until Caleb starts to wonder if Ava is playing him too.

Ex Machina reminded me that there are two ways you can start a screenplay. You can go the “introduce the main character’s world first” route, where you show Luke’s life as a frustrated wind farmer who wishes he were a star fighter battling the Empire. This is the method taught in most screenwriting books. The other method is to “jump right into it.” In this approach, you skip all those character establishing scenes and throw us into the story, as they do here with Ex Machina. I mean we have a single scene – Caleb writing code – before he’s off to meet Nathan.

There are pros and cons to each. In the “introduce the world” scenario, we get to know the character better. We understand his world, his backstory, his hopes, his dreams, his flaws. Because we know him better, we’re more likely to relate to him and root for him. The problem with this approach is that it can be boring. Scripts need to move and if we’re sitting around for ten scenes just “getting to know someone,” we’re probably going to get bored.

The “jump right into it” route takes care of this issue. We’re entertained right away so we don’t need to worry about that pesky drawn-out first act. The problem with this approach, of course, is that we don’t get to know our character as well, which means you run the risk of the audience not giving a shit because they don’t feel close to the person leading us through the journey.

A common solution is to quasi-combine the two options. For example, The Matrix throws us into the story right away, but then takes a step back and introduces us to Neo’s world. Or, you can throw us into the story right away, like Garland does here, and try to slip in bits and pieces of your protagonist’s life where you can. Which is hard because the best way to set up a character is to see him in his environment. But it can be done. For instance, Garland uses this scene of anticipation where we’re driving to Nathan’s mansion to slip in a few details about Caleb’s character. The point is, it’s tricky. But as long as you understand the challenge, it’s possible to overcome it.

As for the rest of the screenplay, I thought it was good, but not great. I loved the use of the “Great Gatsby”-like mystery box of “Who is Nathan?” I was pumped to find out. I also enjoyed the initial scenes between Caleb and Ava. But as the script went on, it started to feel like I was ahead of the story. What pulled me into this script were the mysteries. And those seemed to be answered fairly quickly. Afterwards, we’re left with some compelling questions and interactions (what is consciousness? Can a man fall in love with a machine? Is this all a game?) but the script was never as effective as when it had those mysteries going.

This is something I’ve noticed in a lot of scripts. Writers include early mysteries because they’re easy to create. Everything about the world is new, so it’s not hard to say, “What’s this person hiding?” However once they’ve got you hooked, they move on and focus on other things. But it’s kind of like hooking a kid on candy and then trying to feed him broccoli. The kid doesn’t want broccoli. They want candy! It is harder to introduce mysteries as the story continues, but it’s worth it to try. I know I would’ve liked an extra mystery or two in that second and third act.

Despite the eerie tone of this man cut off from society left to roam an immense mansion where he’s being watched by numerous cameras, his only interaction being with this weird creepy billionaire and his robot, the story doesn’t quite have the endurance to make it to the finish line. I think what it needed was another subplot, a little more going on inside the house, and a solid mid-point shift. Remember, mid-points are where you throw something at your audience that changes the story up a little so the second half doesn’t feel like a repeat of the first half. I didn’t see that here, and the story suffered a little as a result.

Still, the writing was strong, as you’d expect from someone as accomplished as Garland, and it passed the ultimate story test: Did I want to find out what happened in the end? The answer to that question was yes, and for that reason, it’s worth the read.

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: The script needed another mystery or two. And I think I found an opportunity that Garland missed. When we first meet Nathan, he gives Caleb a security card that he explains will let him into some rooms, but not all of them. What Garland probably should’ve done was highlight one specific room that was locked that Caleb was never allowed to go inside. I’ve never seen this device NOT work before. You use that room throughout as a mystery box, with the audience desperately anticipating what’s inside. That would’ve helped here, as the script ran out of mysteries too early.

Read as far as you can and tell us which script you liked best in the comments!

TITLE: The City

GENRE: Futuristic thriller

LOGLINE: An illegal artist hides in a nuclear wasteland to avoid a death-sentence but is forced back in an exchange to save his friends who have been kidnapped.

WHY YOU SHOULD READ: I’ve spent a bloody long time on this script – over 5 years – and it’s completely different now to what it was when I started, as it should be. The story at the crux of it remains the same, and that’s what it’s all about. It’s a small story in a bigger world… As Jim Jarmusch said, “I’d rather make a movie about a man walking his dog than about the Emperor of China.” Anyway now that it’s “done” I need to get it out there, and I’m at a bit of a loss as to how to do that! Sure I can send out script queries but I feel this needs a real read and review – good, bad or otherwise. I’ve had friends and friends of friends read it for me, but they’re probably just being nice when they tell me what they think. I want professional words of wisdom because if there is one thing I can do it’s take them, take advice, hit notes, improve, and ultimately, from this, write in a way that will help me progress my career. This script has been a part of my life for so long I’m feeling pretty lost right now! This feels like a handy next step…

TITLE: They Ate the Horses

GENRE: Adventure/Horror

LOGLINE: A century after mankind’s near extinction, a daring teen eludes her overprotective father, risks an adventure to a neighboring town, and quickly discovers slavers are the least of her worries.

WHY YOU SHOULD READ: Hey! Hey everybody! Another post-apocalyptic wasteland! Someone tell the DP to get the “grey” filter ready! You may notice that this is sarcasm. Glowing sarcasm, in fact. We’ve populated this world with likable (and not-so-likable) characters, danger, humor, and yes, even color. Come for the colorful take on life after (most) humans, stay for the ridiculous twist. I hope you have as much fun reading it as we did conceiving and writing it.

TITLE: The Benefactor

GENRE: Psychological Thriller

LOGLINE: A young widow discovers her husband’s accidental death is the latest in a series of murders-for-profit reaching back more than a decade.

WHY YOU SHOULD READ: This is based on my published novel. In its review, Mystery Scene magazine described the book as “a story Hitchcock would have approved of.” Exactly what I was striving for.

TITLE: PARKING ENFORCEMENT

GENRE: Buddy Comedy (Step Brothers meets 21 Jump Street)

LOGLINE: When two bumbling brothers get their shot at a badge after twenty years in Boston parking enforcement, they will uncover a police conspiracy forcing them to go after the very people they’ve spent their entire lives wanting to be a part of.

WHY YOU SHOULD READ: After failed attempts at recognition with less commercial fare, this is my first stab at a highly structured, broad commercial comedy. The initial inspiration for this came from a single question: what if The Departed was a comedy? Boston is always used in a very serious way where the deep roots of cops run for miles, so I wanted to take that aspect of it, flip it on its head for a comedy (a la The Heat) and ask a secondary question around, what if two people who had the badge in their blood wanted to be, but couldn’t? And, then finally, what if they were completely opposite brothers? I’d love to better understand what works here and what doesn’t from a story perspective. To date, this is the most structured and outlined script I’ve ever written.

TITLE: Broken Vessels

GENRE: Body-switching

LOGLINE: A New York City policeman tracks a serial killer through 700 years of dead bodies to find the secret to an immortal curse.

WHY YOU SHOULD READ: I’ve been a quarterfinalist in the Nicholl three times in four years (with two different scripts). I was a semifinalist in the Big Break the one, and only, time I entered. Frequent site contributor walker listed one of my scripts (not this one) as the best amateur script he’s ever read. I wrote this script with actors in mind. It is Oscar-bait for the Denzel Washington’s and Ryan Gosling’s of the acting world. Plus, you’ve said you are always looking for the perfect body-switching script. What if this is it?

Beyond that: At 40, I am stuck in a middle management job that requires me to get up at 3:30 in the morning and work 11 hours a day 6 to 7 days a week. I have a daughter at NYU, the most expensive school in the country, and my wife is now expecting our fourth child. I know I can write and, up until now, I have been willing to wait for my chance. Circumstances have conspired to put me in a more “Kyle-Killen-when-he-wrote-The Beaver” frame of mind. Were your site to bring that chance to me, I would not forget it—the way others that got their break from your site seem to have forgotten it.

Genre: Horror

Premise: A prequel to The Shining, The Overlook Hotel chronicles the 1918 construction of the infamous hotel.

About: Things seem to be really coming together for Glen Mazzara. The longtime TV writer became headline news in the trades when he took over as showrunner for Frank Darabont on The Walking Dead, follwing Darabont’s ugly exit from the show. Most predicted the series would suffer in quality, but Mazzara proved them all wrong, bringing the series to new heights. He’s now making the transition into features, writing the script for Hancock 2, and writing this high profile scarer for Warner Brothers. The film will be directed by the suddenly resurgent Mark Romanek, who had to wait 8 years between films after his critically appreciated “One Hour Photo” and his moody euthenaisa-esque “Never Let Me Go,” the film that got him this job.

Writer: Glen Mazzara (based on the prologue in Stephen King’s “The Shining.”)

Details: 115 pages – Studio draft (April 30th, 2014)

A special “ooh ooh ooh ah ah ah” shout out to everyone on our very last day of Halloween coverage. And what better way to celebrate the spookiest day of the year than with a review of The Shining prequel script!

As much as my bullshit meter goes up when studios try to capitalize on old horror properties (if they were such good ideas, why didn’t they make them a long time ago?), I’m more worried about what this means for writers. Between the new “Conjuring” universe approach and now another “based on a big property” release, I’m nervous about what this means for writers trying to sell horror. Horror has been one of the few genres that embraced new ideas from the spec market. If it goes the way of the action and adventure genres, focusing only on IP, that’s one less genre we have to play in. I hope I’m overreacting.

Now it might surprise some of you to know that I never really embraced The Shining as one of the horror greats. But I blame that less on story and more on Kubrick. I know he’s one of the masters. But his nihilist view of the world has never really gelled with my more hopeful view of things, so there was always a disconnect there. With that said, Jack Nicholson gave a superb performance, and the film was undeniably creepy. Let’s see if Mr. Mazzara can live up to that pedigree.

The year is 1918 and Bob T. Watson, husband to one of the richest women in the world, is looking for a way to be his own man – to create something that he can be known for, as opposed to always being seen as, “that rich woman’s husband.”

His vision is to build the grandest hotel in the nation, a breathtaking behemoth in the Colorado mountains. His plan is to create something so extravagant that the rich and famous will travel across land and sea to stay here.

But things don’t start out well. As a line of trucks carrying building supplies snake their way up the mountain, a flash flood hits. Bob can only watch from above as everyone in the trucks is violently wiped out. Decapitations. Bodies being severed in half. It isn’t pretty.

But Bob is a business man and decides to push on. He continues to build the hotel, despite the fact that some believe the land is now cursed.

Unfortunately for Bob, his problems aren’t limited to flash floods. His 8 year old son, Richard, “sees things” and is constantly claiming to spot dead people, including those men who perished in the flood. He also claims to see a woman named Norah, a woman who died 40 years ago on this mountain during a winter storm where she ran out of food and had to eat her own babies. Now that is truly disgusting. I hope she at least had some spices to flavor the meat.

Not long after guests start showing up, Bob’s OTHER son (spoiler), 12 year old Boyd, chokes on some meat and dies. This devastates Bob’s wife so much that she goes into a funk, which eventually leads to her falling and breaking her back, paralyzing her. On the plus side, he’s now the husband of the “paralyzed chick” instead of the rich one. Gotta look on the bright side, right?

Not unlike Jack Nicholson’s Jack Torrance, from the original “Shining,” Bob then finds himself having homicidal tendencies. He’s also confused when things just start showing up in his hotel, like a library that he never built, and those infamous garden mazes we saw in the original film.

If Bob wants to save his family along with this hotel, he’s going to have to get his shit together and figure out what’s causing all this madness, a reality we’re fairly sure will never come to fruition.

I’ve never read the book, “The Shining,” so I can’t speak to this prologue that the prequel is based on. But I can say that this very much feels like something based on a prologue. And what I mean by that is, I can imagine this 15 page story that Stephen King wrote, which likely highlighted 5 nefarious events (such as the flash flood), and I can see that all five of those points were dutifully incorporated into the screenplay.

And make no mistake. Those events are nefarious. The flood scene is like nothing we’ve ever seen on film before. It will be amazing. And the scene where Boyd, the son, chokes to death, was particularly graphic and disturbing. But I’m not sure there was anything left to “Overlook.” It feels like a “highlight reel” and nothing more. There’s no story here to hold it all together.

To be fair, the script starts off strong. We’re literally building towards something, and as viewers, we’re excited to see how that’s going to turn out. But the hotel is finished by the end of the first act, and Boyd is dead at the midpoint. From that point on, I had no idea where we were going. I’ve used the analogy before (in Gone Girl) of blowing up the balloon all the way until your climax. Well, Boyd’s death released all the air in the balloon, and we weren’t even halfway through the script. From then on, I’m not sure there was even a balloon to blow into anymore.

The script skittered about with a few cheap scares (seeing dead people) before eventually settling upon Bob T’s failing sanity as a narrative engine, much like the first film. But whereas The Shining built up to the loss of sanity nicely, here it seems to come as a last second bail-out. Like, “Hmm, nothing’s really happened for 30 pages. Maybe Bob should go crazy now.”

I’m not sure how this should be fixed other than to suggest a clearer goal be put in place after Boyd’s death. When a story wanders, it often comes back to an inactive protagonist. If the protagonist isn’t ACTIVELY pursuing anything, the story itself feels inactive. By giving the protagonist a goal, then, the script gains purpose. It gains direction.

So maybe Bob is looking into his son’s death. Whereas he didn’t believe in the paranormal before, the strange events surrounding Boyd’s death encourage him to find the truth. This gives the story momentum while still allowing you to do everything you were doing anyway (introducing scary garden maze scenes and such).

Also, something that bothered me from the original Shining was still in play here, which is that I never truly understood the rules of this universe. The big twist at the end of the original was cool at first, until I started to think about it, and then it didn’t make sense at all. I don’t want to get into spoilers here. But at the end of Overlook, there are some things that sure are spooky when you first see them. But then you’re like, “Wait a minute. Does that even make sense?” Like the library that just appears in the hotel. What is the logic behind that? Why would ghosts sneak a library into the hotel? Are they vociferous readers?

Anyway, the script isn’t bad, just light on story. I do think they should make this into a movie. The setting is unique for a horror film (the year adds a new dimension to the “spooky hotel” tale) and it’s a better set-up than most of the horror ideas out there. Certainly better than “Ouija.” But this highlight reel needs to be turned into more of a story. I hope they pull it off.

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Something that bothers me in any film is when a writer knows they’re going to kill off a character, so they never develop him. The problem when you do this is that when these characters die, we don’t feel anything. This is what happened with Boyd’s death, the older son. He was mentioned 1/10th as much as Richard (the other son), so when he died, despite it being an awesome death, I didn’t feel anything for him. You should treat any dying-later character with just as much depth and complexity as your other characters. The more that’s going on with them, the more shocking and more impactful their death will be.

At 29, Adi Shankar is one of the hottest young producers in town and one of the few guys who isn’t afraid to produce risky R-rated material. His credits include The Grey, Dredd, Lone Survivor, and A Walk Among The Tombstones. He’s also releasing one of my favorite scripts, The Voices, next year.

Shankar’s counter-culture approach extends to the web as well, where he’s produced the short film, “Punisher: Dirty Laundry,” starring Thomas Jane and Ron Pearlman, and “Venom: Truth in Journalism.” His newest offering is the animated dark comedy mini-series, “Judge Dredd: Superfiend,” which you can go watch right now!

SS: Before we get into writing, I’ve always admired your ability to make these risky R-rated films in an industry that’s typically afraid of that space. How do you pull it off?

AS: Most companies egregiously overspend on overhead. I believe in a lean, tight-knit team, and it allows me to be cost effective in all my decision-making and affords me the financial freedom to make “riskier” films.

SS: Okay, moving on to my bread and butter. I always talk to writers here on Scriptshadow from a writing perspective. But producers see the craft differently. From your side of the wall, what advice can you give writers just starting out?

AS:

1. When starting out, don’t be discouraged by people with the “9 to 5” jobs. They are the ones who urge you to “be realistic,” goad you as you attempt to understand yourself, and bring you down during your sporadic, minor, yet intangible victories. Take solace in the fact that these “9 to 5-ers” will get their minds blown when they see Katy Perry (or equivalent) at a restaurant one day and it will become the single defining moment of their lives, while you are attempting to add to the discourse of the culture.

2. Write every single day. If you don’t, writing will always just be your hobby. (Note: This doesn’t mean quitting your job)

3. You should read 200 “great” professional screenplays before you start writing so that you know what you are aspiring to be. The resources (scripts, interviews, trades, etc.) you have access to today as a beginning screenwriter are unparalleled and were only available to previous generations by becoming someone’s bitch. For the first time, you don’t even need to live in Los Angeles to be a screenwriter or to have your work read.

4. Follow the plethora of online recourses that weren’t available to past generations i.e Blacklist and the tracking boards, to see what’s selling, what’s getting heat and not selling, what’s getting acclaim, and what’s getting acclaim but not selling. This will inform your understanding of the marketplace and the business of screenwriting.

5. Write and produce for the Internet. It blows my mind that more people aren’t attempting to build a web footprint. Check out NEXT TIME ON LONNY it’s simple, smart, funny and is a blueprint for anyone who aspires to create.

SS: What about writers who are closer to the mid-level? These might be writers on the verge of breaking in or who have just punctured the lower levels of the industry. Any advice for them?

AS: The biggest misconception you have to psychologically fight is this idea that once you cross a certain imaginary threshold in your career you’ll feel “made.” You’ll never feel truly “made.” While, like any rote skill, things do get easier over time, you struggle consistently at any level and actually feel more not less pain at every higher rung on the proverbial ladder.

This industry is convoluted and hard for everyone: Whether you’re a novice writer or Robert Towne, a beginning actor or Russell Crowe, an assistant at the mailroom or Stacy Sneider there is always arbitrary red tape, infuriating walls built by insecure middlemen, and some asshole that just wants to fuck you over for the sake of fucking you over. You are constantly living with a damoclean sword over your head and a lottery ticket in your hand, one bad decision away from being black balled and one great sentence away from becoming the next big thing.

SS: Everybody’s trying to get their idea/script/project to the guy who’s able to say “yes” and the movie is greenlit. You’re occasionally that guy. In your best estimation, what do you need from a screenplay to give it that green light? What makes you say “yes?”

AS: Two things need to happen:

1. I need to respond to it creatively. (Note: I detest the routine and respond to material that is unconventional).

2. The market needs to respond to it financially.

As you can imagine 1 & 2 are almost always at odds with one another.

To be specific, by the “market” I don’t mean the movie-going public. Unless you are operating at the highest of levels (aka the Chris Nolan, Spielberg, JJ Abrams level), producers/directors don’t make movies for audiences, we make movies for distributors, and are beholden to what distributors believe audiences want (read: the last successful movie).

Second only to the inability of distributors to match a prospective customer with a specific product in a cost effective manner, the biggest problem that our industry needs to solve is the issue of access. Information is a commodity to the detriment of the business.

So my advice to writers: Figure out what the market wants and write the best version of that as quickly as you can before the market changes. For example, in 2008 it was quirky indie comedies, in 2010 it was $25-30 million dollar action movies, in 2012 it was $3 million dollar horror movies. Pretty soon the $7-12 million range, which for years had been the “no mans land,” is going to be the independent sweet spot.

SS: This leads me to a question I’ve always had. This industry is actor and director driven. If you get a big actor or director attached to your script, the project has a much better chance of getting made. So as a writer, should I be trying to find ways to get actors and directors to read my script so they’ll attach themselves, THEN come to you? Or should I come to you first and let you use your relationships with actors and directors to put that project together?

AS: It depends. I prefer STD free scripts, but sometimes if the attachments are so great then everyone is obviously going to pay more attention. Again, it depends on the producer and the genre of the script.

By and large I’ve found attachments for the sake of attachments to be a detriment. I once read a script that I thought was great but the manager insisted that a much hated director had to be attached to direct. That manager ultimately screwed the writers by making their very makeable, highly marketable script instantly un-makeable due to a bogus attachment. The marketplace moved on and the window of opportunity to make the film passed.

Also, when you’re attaching someone, realize that you are getting in business with the person, that person’s reputation within the industry, and reputation with the potential buyers for your project, not their credits.

SS: You sell your movies to many foreign territories, which is a way to fund your movies (or most of them) before they even get made. Film is becoming more and more of a global business. Should screenwriters be accounting for that in their screenplays? Should we be writing differently? How does one write for a “global audience?”

AS: Don’t worry about this. Just try to tell a really great story. The more you get caught up in trying to retrofit a human story into something that will “sell globally” the more you risk diluting your material.

SS: You were telling me about a project awhile back, an idea you came up with. And you said you went out and found a writer for that. How does a writer (say, a writer reading this right now) become the person you call to write your movie? How does he get in that room with you?

AS:

Step 1: In that particular instance the writer had written the last movie by the director whom I was developing the idea with. The brutal reality is that writers almost always get hired for an assignment because of a working relationship.

Step 2: When I call writer’s representatives, it’s preferable that they be “user friendly.” I’ve passed on working with so many talented writers because I thought their agent or manager was a cheese dick and was going to cause problems down the road.

Best blanket advice I can give to an up-and-coming writer:

Find a talented director at “your level” and partner with them and become “their writer” and start operating as a team (See: Wigard, Adam & Barrett, Simon). So many talented directors are in dire need of writer/producers to execute their wonderful ideas and more importantly for a creative partner who isn’t a cornball producer trying to pull a silver dollar out from behind their ear. This journey in 2014 is now too complicated and frankly impossible to do alone, so build a collective.

To be a douche and quote myself:

“Hollywood is undergoing a massive decentralization right now, caused by the ongoing collapse of the studio system and the rampant greed of the 90’s. It means that collectives of people who can consistently and autonomously deliver a product will have an advantage. They will help you sift through all the crap Hollywood throws at you, and more importantly give you the kind of creative autonomy that today’s non-celebrity filmmakers can only dream of.”

SS: Is it important that a writer be “good in the room” with you? Do you have to feel a chemistry or a certain energy and knowledge from them to work with them? Or do you only care about how good of a writer they are?

AS: Being good in the room doesn’t matter. I don’t want the guy who sells me the car to design and build the car too. I’m also not looking for a friend, girlfriend, roommate, drinking buddy, flip cup or beer pong partner. Humility, writing skills, and general insight about life that can be retrofitted into a screenplay are all that matter. I do meet many writers who are whiney and unloved and complain about “how unfair the industry is” and I generally want to bitch slap them … so don’t be that guy.

SS: I ask a lot of producers what they want from a script, and they almost always say, “I’m just looking for something great.” Is it really that easy? Or are there more factors involved?

AS: It’s that simple. We just want great material. Great material will attract a great director and that package will attract “bankable” (note: as an actor myself that word pisses me off) actors. It will make distributors fight over the distribution rights. Give me SOURCE CODE and I’ll produce and deliver you a finished film via text message faster than you can say Punisher Dirty Laundry.

SS: Does a writer need an agent for you to read their scripts? If you do receive scripts outside of agents, where do they come from?

AS: It’s a legal grey area. I desperately want to discover a great script from under a rock but legal reasons make it challenging.

Traditionally, success in this business has been proportional to one’s access to information. In their inevitable next evolution, online screenplay resources like ScriptShadow, Trigger Street, and Blacklist are very shortly going to revolutionize the way producers/actors/directors access material and democratize the green lighting process.

Before the Internet, an agent had the ability take a script off the shelf and present it as brand new. Tracking boards made the spec market efficient. Blogging made it possible for one to dissect material and allowed the industry to congregate behind risky but great material. The next tectonic shift will be numerically driven and force an egalitarian more “crowd sourced” process to the chaotic status quo.

On the issue of agents, keep in mind that reps are useless unless you have a career spark. To be clear, it’s on you at every juncture in your career to create a spark for yourself. If you are unrepped and looking for your big break right now the web stuff is the best platform to create a spark. What reps are really good at is turning a spark into a flame and the best reps will help convert that flame into a forest fire (see: Jennifer Lawrence and Bradley Cooper).

SS: Finally, we all know Hollywood prefers intellectual property that’s already proven. Since all screenwriters are poor and can’t afford to buy flashy intellectual property, what can they do to compete with these guys?

You bring up an interesting point. In television, the writers are the producers. This should be the case in the movie business as well, as it would eliminate a lot of the infrastructural problems we face.

A trend I’ve noticed is that once writers become deemed “professional writers” many take the mentality of “I need to be paid to write.” While I can sympathize, the fact of the matter is great screenplays are the lifeblood of this industry. If you have a great story that must be told … fucking write it.

It doesn’t make sense to waste time waiting for some jerk off producer or studio to “buy your idea.” Own it, control it, and if you really are that good you may have just written the next DALLAS BUYERS CLUB, PRISONERS, or LOW DWELLER (OUT OF THE FURNACE). Every major movie star and every major director needs a “next movie” and even those we have deemed gods at the moment are beholden to access to great material and are at the mercy of those who control it. Unencumbered scripts are easier to make.