Genre: Horror

Premise: A non-traditional horror tale centering around three young women at a girl’s boarding school.

About: “February” made the 2012 Blood List, but the more interesting story is who wrote it. Now I didn’t know this before I read the script (I try to research the screenplay after I read it so I don’t go in with any preconceived notions), but the script was written by Osgood Perkins. Does that name sound familiar? It should. It comes from some prime horror stock. That’s right. Osgood is the son of Anthony Perkins, who played Norman Bates in Psycho. Now before you assume he got this far through nepotism, you might want to read the script and then my review.

Writer: Osgood Perkins

Details: 111 pages – June 2012 Draft

Halloween Madness at Scriptshadow continues!

Halloween Madness at Scriptshadow continues!

In the casting profession, you’ll often hear casting directors talk about going through hundreds of auditions in order to get to “the one,” that one actor who makes everyone in the room sit up and pay attention. They talk about noticing that “special something” in the actor, an indescribable secret sauce that you can’t quantify.

Every once in awhile, I’m lucky enough to have the same experience with reading screenplays. You see, the reason that having a unique voice is so often touted as the key to breaking in, is because so much of what we read as readers is the same. It’s written the same, it’s structured the same, it’s imagined the same. So if you find something that doesn’t feel like the rest, you’re immediately drawn in.

I liked Perkins’ writing here so much that I’m going to implore you to find the script and read it yourself before you read my review (plenty of people should have the script in the comments). The beauty of this script is in the way that it grows and surprises you. Reading plot points beforehand is going to take away from that experience. With that warning, let us begin.

“February” is an aptly titled script as the word is meant to convey a feeling. The cold empty air of a February morning. It’s a common practice in Perkins’ writing. February is 75% atmosphere, and the best script I’ve ever read at using atmosphere to engage the reader.

The story starts out at The Bramford School For Girls, on the week the parents are taking their kids away for the weekend. 17 year old Rose, however, informs the headmaster that she miscommunicated the day to her parents, and will therefore have to stay at the school an extra night.

We quickly find out Rose is a little con girl. She orchestrated this hole in her schedule so she could spend the night with her boyfriend. But her plans are thrown into disarray when the headmaster assigns Rose to watch over 13 year old Kat, another girl whose parents didn’t show up.

Kat is a weird kid. She’s plagued with that “something’s off” look in her eyes. You can routinely expect a 1-2 second delay in every response she gives. But Rose could care less. She’s all about hanging out with her boyfriend, and leaves Kat at the empty school to fend for herself.

In the meantime, we cut to a plane flying into Providence, and meet another strange character, the 20 year old, Joan. Joan looks even more out of it than Kat. What’s going on here? Is there some sort of virus spreading through the country making women lose their shit? We’re not sure. All we know is that Joan’s surprised to find a hospital bracelet on her wrist. How did it get there? And how come she doesn’t know?

When she lands, Joan heads out of the empty airport into the beginnings of a winter storm. A seemingly sweet married couple in their 50s spot her. When they hear she’s going to the same town they are, they offer her a ride. Unsure at first, she eventually agrees.

Back at the Girl’s School, Rose comes back from her date, only to find Kat missing. She sneaks around the campus looking for her, eventually finding her in the most unlikely of places. It is a place that will set the stage for a shocking turn of events which will bring Rose, Kat, and Joan together in a way we never could’ve expected.

I’ve mentioned this before, but when I really like a script, it’s hard for me to break it down. I’m so caught up in the story, I’m not paying attention to a lot of the technical aspects. This is the ideal scenario. You want your story to be so compelling that the reader never has a chance to understand why it’s working. They’re too busy flipping through the pages, wanting to find out what happens next.

This it the most atmospheric script I’ve ever read. Atmosphere is essential to horror screenplays. You don’t have the music score doing the work for you as your characters walk into danger, so it’s what you describe and how you describe it that creates the suspense and the tension to pull your reader in. Here’s an example from “February,” a quick excerpt from a scene in the cafeteria.

Notice the sounds and images here. The kitchen door, whining. The man’s footsteps, crunching. The focus on how the man walks, having to pull his weight along. The sound of the refrigerator fan humming. Perkins pays attention to all the little details surrounding the moment in order to bring the moment itself to life. Now you have to be careful about this. You don’t want to overwrite. But readers will give you a little more slack when you’re great with description, as Perkins obviously is.

But what really pulled me in here was the puzzle. The screenplay is set up sort of like Pulp Fiction, where you’re bouncing around from character to character, trying to figure out how it all fits together. I mean when we jumped to Joan for the first time on the plane 40 pages into the script, I threw up my hands and was like, “Where the hell is this going?” The last thing I expected was to be leaving the boarding school, and my brain had to work overtime to figure out how those two threads were going to come together. I loved it.

Perkins also has an amazing ability to make even the most minute moments mysterious. For example, this is how Joan was introduced: “She’s roughly 20 but looks older, some of the brilliance having gone from her eyes.” (line space) “If you asked for her name, she’d tell you it’s JOAN.” You see what I mean. Even a simple character introduction comes with a mystery! Her name is Joan. Or maybe it isn’t. How could something as simple as a name come with such uncertainty??

Now this script isn’t going to be for everyone. Some are going to find it slow. Perkins makes you read for a long time before he rewards you with any payoffs, and his focus on description and ambiance is so heavy at times that it might turn people off. I can already hear some of you, while reading it, saying, “Get to the point already.”

But I loved it. There’s something inherently suspenseful about his style, allowing even the most mundane scenes to come alive. For example, when the ultra-fragile Joan is having breakfast with Bill (the husband character who gave her a ride), we’re convinced that he’s angling for something here, that he has a possibly evil agenda. Which makes us worried for Joan. But at the same time, we haven’t figured Joan out either (what was up with that hospital bracelet??), and a part of us is wondering if she’s the one we have to worry about. I rarely feel so much energy underneath a scene that was, basically, two people talking over a meal.

But the kicker of why this horror script is so much better than everything else out there is the writer’s choices. As I like to say (or at least, am about to) “Voice is choice.” (major spoiler follows) Had you given 100 writers the premise of, “Write about a psychopathic 13 year old killer,” 99 of them would’ve written a straight-forward slasher type script following a 13 year old girl going from victim to victim. “February” is anything but that. It deftly weaves three giant puzzle pieces together into one of the more satisfying (and creepy) revelations I’ve ever come across. Remember this always, guys. When you come up with an idea, sit down and think about EVERY ANGLE you can tell that idea from. Don’t just hop into the first approach that comes to mind because that’s probably the most boring approach.

“February” reminded me a lot of Wentworth Miller’s writing, but I think Perkins is even better. If I were a horror screenwriter, I would say that these two guys are the ones you want to be studying right now. They’re the ones with the most interesting vision. Even though I thought Interstate 5 was decent, the writing here really shows how big the gap is between average and great. You really see how good writing can elevate something. What a script!

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[x] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: If you love writing description but you’re tired of the screenwriting Gestapo telling you that there’s no place for excessive description in screenwriting, here’s a workaround for you: Hide your description INSIDE OF ACTION. That way, the description doesn’t sit out on its own and bore the reader. For example, let’s say you want to describe the kitchen during a night scene, that it has “slivers of moonlight” that “shine off of hanging pots.” Don’t start your scene with that description. Wait until there’s some action in the scene and then squeeze the description inside of the action, like Perkins does. Here he is describing Rose in the kitchen: “She steps deeper into the dark room, guiding herself by the slivers of moonlight that shine off of hanging pots and pans and along the sharp edges of metal counter tops.”

Correction: Soo Hugh is not a man! Sorry for the screw-up.

Genre: Sci-fi

Premise: When a group of children in a small town start exhibiting dangerous behavior, a child care specialist must figure out the link between them, a link that may be otherworldly.

About: The Visitors (now renamed “The Whispers”) is an alien invasion series executive produced by the one man you want your alien invasion show produced by, Steven Spielberg. It’s been written by Soo Hugh, who’s still looking for her big break. She’s written for The Killing and Under the Dome. But writing for Spielberg is by far her biggest accomplishment yet.

Writer: Soo Hugh (based on a Ray Bradbury story – “Zero Hour”)

Details: 59 pages – 1/09/2014 3rd Draft

Halloween madness continues. But today, we’re moving from serial killers to alien killers. Or, more specifically, child alien killers!

Uh-huh. Uh-huh.

Can’t think of anything scarier than that now can ya?

Let me say this. I went into this not knowing what it was about. So once I realized what the premise was, I kinda lost some enthusiasm. Because here’s the thing. I’m always asking for irony right? I’m always saying, “Make sure your premise is ironic if you want people to read it!” And The Visitors is ironic. Aliens are using the most unsuspecting resource you could imagine to take over the planet – children!

Little children aren’t supposed to be able to do something as immense as take over a planet. Hence the irony.

But at what point does an ironic concept turn silly? I’m having a hard time buying into this premise of little 7 year olds taking down society. I mean, for argument’s sake, let’s take it to the extreme, make it SUPER ironic. Let’s say that BABIES are taking over the planet. That’s ironic. But a good idea? I don’t think so. Unless it’s a comedy. I guess the first thing I learned from today’s read is that there’s a limit to how far you can push irony.

Anyway, The Visitors focuses on Baltimore FBI agent and child care specialist, Claire Bennigan. Claire’s had a tough couple of years. Her 7 year old son, Henry, lost his hearing due to a virus. And a couple of months ago she lost her husband due to death. Luckily, she’s finally back on the saddle, taking on a case where a young girl has murdered her mother.

Claire checks it out, learning that the daughter claims to have been manipulated by an imaginary friend named “Drill.” This is curious, since Claire recently heard of another elementary schooler who built a bomb at the request of an imaginary friend named, “Drill.”

All the other agents think this is some Slender Man nonsense. Some boogeyman the kids have made up and who a few have taken too far. But Claire isn’t so sure. Kids don’t know how to build bombs, do they?

Meanwhile, on the other side of the world, in Algeria, they’ve just found a freaking crashed spaceship! Nobody’s in the ship. But curiously, underneath the ship is the jutting wreckage of a U.S. F-22 military jet. And when they clear the wreckage, they realize there’s no body inside. Hmm, what could THAT be about?

As more and more children claim that “Drill” has asked them to participate in “the game,” Claire must put together what the game is and how it ends. Because if the kids she’s interviewed are any indication, the game ends very very badly.

I’ll get this out of the way first. I’ve said it before. If the reader doesn’t buy into the premise, nothing else you write will matter. They’re already on to the next script, even if they’re still physically reading yours. This actually JUST happened to me last week. I found a really great script, sent it to a producer, and he admitted he loved the writing but he didn’t enjoy the story cause he never bought into the premise.

This can be tough and confusing on writers. They’ll send a script out, get a “no” back with no explanation, and, being writers, immediately assume the worst and think they’re the shittiest writer on the planet, head over to the local wine & spirits, buy the cheapest largest bottle of whiskey they can find, and drown their sorrows in it. All when it MAY just have been that the reader didn’t like the premise.

So where does that leave me and The Visitors? Well, I’m sorry but I just can’t see a 7 year old ordering a bomb strike on France (this didn’t happen but it’s plausible with the way the story’s going).

But how was the rest of the pilot! Well, it was pretty good. I mean, Soo definitely knows what he’s doing. The opening scene is great, as a mom follows around her daughter who we know is leading her into a death trap. There were plenty of other suspenseful moments like this (when the Algerian General greets the Americans, he doesn’t show us the picture of what he’s found in the desert. He shows the characters – we have to WAIT to find out what it looks like).

And Soo keeps things fresh with a lot of mystery boxes as well. There’s a man who wakes up in the middle of New York covered in tattoos. What’s he doing there? And why is he screaming in Arabic? There’s the crashed military jet underneath the spaceship. How the hell did that get there? And where is the pilot?

Also, like in any good teleplay, the main character should be a mystery box in themselves. They are your “tip of the iceberg” and the next 7 seasons should reveal what’s underneath the water. Claire’s husband just died. But there are hints that she may have been involved somehow. We want to know more.

There was also something kinda cool I noticed. Again, the key with any story is keeping your audience around. You have to give them reasons, carrots dangling in front of the donkey if you will, to keep reading.

A clever little trick, then, is to go to a commercial on a cliffhanger – such as your characters looking off at something amazing that we don’t see yet – then, when you cut back from commercial break, DON’T show your readers that thing. Go to another set of characters who you need to do some boring exposition scene with. You could even throw in another scene after that. Then, and only then, do you cut back to the “what did the characters see” scene. You use the suspense created from that scene to sandwich in other less exciting scenes. We’ll keep watching because we’re high on the suspense wave.

Nitpicks: Now, I have a few things to nitpick here. Number one, I think we’re done with the mysterious tattooed character thing. When SNL starts making fun of something (they did an amusing trailer mash-up for all the YA novel movies) that usually places it squarely in the cliché category. It’s time to think of something besides tattoos.

Next, I don’t know if this is just me or not, but when I see a deaf kid in a show/movie, I groan. Besides being cliche, there’s something desperate about it, like you want us to love your kid and the parent so much that you stoop to the level of making him deaf. It’s too manipulative.

Now there is a way to subvert this and other clichés. You research the shit out of the subject matter so it comes off as authentic and honest. If you really know what being deaf is like and you’re able to show that to us specifically, we’ll buy in. But if all you know about being deaf is what you’ve seen in movies, and you include a deaf character, it is almost certain that that character will reek of cliché.

Finally, drop the weird character names. You’re not a Hollywood couple. You don’t have to name your kid after a walrus placenta (“Walcenta?”). Weird names draw attention to themselves and they irk readers. Look no further than the comments section of Scriptshadow to see it in action. “Minx” is not a real name for a kid. At least I’ve never seen it before. So whenever the name came up, I winced.

Despite these criticisms, I see Soo as a good writer. While I didn’t love this, I still stuck around to see how it ended. I’m just not sure this is a good enough (or big enough) idea for a TV show, but I’d love to be proven wrong.

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: When you’re approaching a big or dangerous or scary moment, make sure to TAKE YOUR TIME and milk the suspense beforehand. I see too many writers eager to get right to the good stuff. No. Make the audience WAIT for the good stuff. In the meantime, look for fun ways to prolong the anticipation. In the opening scene, Amanda, the mom, is chasing Harper, who runs up into her tree house. Harper is acting strange and we know something bad is coming. So does Soo say, “Amanda climbs the ladder and corners Harper?” No. That would be too fast. As Amanda climbs the rungs, Soo points out that each step struggles with the weight of an adult. Any second, the rungs could collapse and she could fall. Those are the kinds of things you want to focus on your way to the big moment. Draw it out!

Genre: Horror

Premise: The son of an infamous serial killer goes on the road with the daughter of one of the victims to find and stop his father.

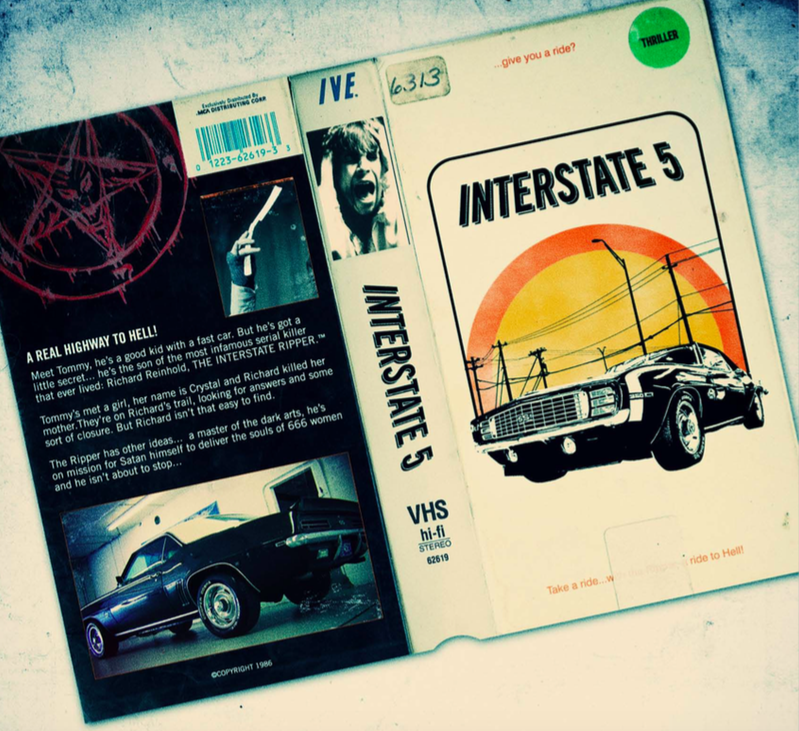

About: Today’s spec made The Blood List (the annual list of the scariest screenplays) in 2012 and resulted in the writer, an unknown, getting the job to write the new Texas Chainsaw Massacre film, Leatherface.

Writer: Seth Sherwood

Details: 105 pages

Interstate 5’s cool title page!

Interstate 5’s cool title page!

It’s Halloweeeeeeeeeeeeen!

Well, it’s almost Halloween anyway.

Actually, it’s still 11 days until Halloween.

But that’s not going to stop us from enjoying the most unnecessary holiday of the year, right? Carson! How could you call Halloween unnecessary?? Well let’s think about this for a second. This is a holiday… ABOUT SCARING PEOPLE. Does that make sense to you?

We’ve got holidays celebrating the birth of Jesus Christ. We’ve got holidays celebrating the birth of a nation. Those holidays feel like there are some actual stakes attached to them, to use a screenwriting phrase. Halloween? It’s like a bunch of dope-smoking teens got together and came up with a joke holiday. “Yo man, they should create a holiday for scaring people.” “Yeah man, and like, you should get candy and shit.”

Hey, I’m not complaining. I still have half my stash of single package Reeses peanut butter cups from 5th grade and I plan to ration those puppies out for another seven years at least. Love me some Resses. But it is one of the stranger curiosities of the American calendar.

Although that’s not the reason I picked Interstate 5 for a Scriptshadow review. It’s important for you guys to know what’s required of a script to get an unknown screenwriter (you) that all-important “big assignment.” Sherwood was just another guy trying to break through the Hollywood gates before he wrote this. Now he’s writing a major horror property. That’s a big deal. Not just for the assignment itself. But once you write on a major property, the rest of the industry takes you seriously. So let’s see what was so special about Interstate 5.

The year is 1985. Noted serial killer Richard Reinhold, who was once captured and thrown in prison, escaped eight years ago, and he’s just started killing again. His victims of choice, like most serial killers, are young women. He picks them up along the highway, rapes them, and carves them like a pumpkin.

But this story isn’t about Richard. It’s about Tommy, a 20-something who was unfortunate enough to be born Richard’s son. Tommy’s life has been a nightmare ever since his father was captured, and now he wants to find some closure. He wants to find his father and kill him.

Tommy is joined by Crystal, whose mother was one of Richard’s victims. The two, armed with Richard’s diary, which details every woman he killed and every place that he stopped at, head down Richard’s famous stomping grounds, Interstate 5, trying to catch up to his killing spree.

Tommy also uses a lot of drugs to cope with his shitty reality. Stress and drugs tend not to mix, so everywhere they stop, Tommy’s convinced he sees the ghosts of the dead victims. Crystal, who was very much pro-Tommy at first, starts to freak out about this, cause she isn’t seeing what he’s seeing.

As they get closer and closer to catching his father, Crystal starts to suspect that Tommy’s losing it. That Tommy may, in fact, be BECOMING his father. The reality, however, is much worse than Crystal could ever imagine. The truth is far far worse.

More Halloween scripts coming your way!

More Halloween scripts coming your way!

So what makes a good horror movie? Scares? Blood? Scantily clad women running through the forest at night? I’m sure we could have a lively debate about the answer, but I’ll say this. I was watching my favorite show last night, The Walking Dead, a show that has somehow GROWN its audience with every successive season, and I asked myself, “Why do myself and others like this so much?”

The answer came pretty early on. What The Walking Dead does better than any other horror show (or movie), is that it provides a constant impending sense of doom. In last night’s episode, our group runs into a priest. The priest seems feeble, a coward if there ever was one. But the longer the episode goes on, the more suspicious we become of this man. Is he really just a priest? Is he really out here all by himself? What is he hiding? We’re not sure, but we think it’s something. And that makes us worried for our characters, which is why we keep watching. We want to make sure they’re going to be okay.

There are parallels in Interstate 5. I have to admit that the first half of the script was a little bland. They’re basically just looking for his dad. Nothing surprising happens. I’d venture to say there wasn’t a single unexpected moment in the first half (you guys know how this drives me crazy – never give your audience what they expect. Find out what they expect and use that against them).

But then the script does introduce a twist, and it’s a pretty good one (spoilers). It turns out Crystal is working with the police. This whole story she’s concocted about Richard killing her mom is a façade so she can use Tommy to find Richard.

Not only does this introduce dramatic irony (we know Crystal’s a cop, but Tommy doesn’t) but it’s the beginning of Interstate 5’s “impending sense of doom.” Tommy’s starting to lose it. He’s starting to see more of these “ghosts.” He’s starting to feel the memories of his father invade him, change him. We begin to realize that Tommy is not as innocent as he seems. He may have those same genetic psychopathic tendencies, which means that Crystal is in danger. The further they go, the more convinced we become that he’s going to do something to her. Just like The Walking Dead. We stick around to see if she’s going to be okay.

But here’s where things get a little tricky. This “impending sense of doom” device only works IF YOU CARE about the character’s safety. With The Walking Dead, we’ve known those characters for 4 seasons. We’ve developed a connection with them. So of course we’re going to care about their safety.

In Interstate 5, I barely knew Crystal. Beyond her having a dead mom (which didn’t even turn out to be true), I’m not sure I knew one unique thing about her. And this is why feature writing is so hard. You have 1/50th of the space (compared to TV) to create a memorable character the audience cares about. Crystal wasn’t a bad character by any means. But I didn’t LOVE her. And I think the audience has to love a character to care whether they get hurt or not.

Despite that, I think Sherwood did a good job delving into Tommy’s character. Just by being the son of a serial killer and all the baggage that comes with that, you’ve got somebody pretty complex. Add to that a pill addiction, visions, flashbacks to happy times between him and his father, and the demons he’s fighting inside when dealing with Crystal, and this is a pretty strong character exploration.

I think that’s what the producers of Leatherface saw in this. They saw an attempt to explore a character as opposed to another boring jump-scare flick or another boring gore-focused flick. Anybody can write jump scares and gore. Literally, a second grader can write, “And then he stabs her over and over again.” Not that I’d want my kid hanging out with that second grader. But the point is, it’s easy. It takes a lot more skill to explore a character. It shows the producer that you’re willing to look into WHY the character became the way he did. And when you do that, you tend to create more interesting characters.

So why didn’t that happen with Crystal? I’ll get to that in the “What I learned” section. But right now, I’ll just say Interstate 5 is a solid worth-the-read. It was teetering between a “wasn’t for me” and “worth the read” for awhile, but I have to admit, its little twist ending there (a total, “How the heck didn’t I see that coming???” moment) solidified it as a script worthy of your attention.

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Remember, when you create “fake” characters, it’s harder to explore them on a real level. One of the reasons I never connected with Crystal was because Crystal’s character was a lie. She wasn’t who she said she was for half the movie. When you’re writing that kind of character, you can’t have the character talk about their REAL life, their REAL experiences, because to do so would give up who they secretly were. So the reader’s only going to get a shell of who the character is. False characters are great for twists, but they provide a challenge on the character development front. So make sure to weigh the risks versus the rewards when you write this kind of character.

Get Your Script Reviewed On Scriptshadow!: To submit your script for an Amateur Review, send in a PDF of your script, along with the title, genre, logline, and finally, something interesting about yourself and/or your script that you’d like us to post along with the script if reviewed. Use my submission address please: Carsonreeves3@gmail.com. Remember that your script will be posted. If you’re nervous about the effects of a bad review, feel free to use an alias name and/or title. It’s a good idea to resubmit every couple of weeks so your submission stays near the top.

Genre: Crime-Thriller

Premise (from writer): Over the course of one night, a reformed father must step back into his murky past to find his criminal brother who is the only suitable donor for his dying son…

Why You Should Read (from writer): I think it was Tarantino that said he’d been staring through the window at the industry for so long prior to Reservoir Dogs’ success that it felt normal for him to be on the outside now. At times I very much feel the same. I’ve had the agents, the managers, the lawyers and done the water bottle tour too. I’ve had scripts go out to all the major studios and prod cos and placed highly or won most of the major contests worth entering. I’ve written/directed my own award winning short films that allowed me to go around the world to various festivals and meet audiences first hand, and I’ve had pilots go into networks and yet I’m still here bashing away, whilst staring through that looking glass and working as a bartender. So, I decided to take stock, go away and write something that I’d want to see at the cinema. A movie me and my buddies would find cool. It’s taken me 13 feature scripts and 4 pilots to “find my voice” and I’m keen to show it to a script writing community that’s as passionate about writing great stories as I am. This is REBEL CITY – with echoes of Michael Mann’s Thief and The Friends of Eddie Coyle – it’s a neo noir crime flick… Hope you like it as much as I enjoyed writing it.

Writer: Chris Ryden

Details: 114 pages

Man, I hadn’t read the “Why You Should Read” until just now. That shows how hard this business is. Chris has already made a ton of headway in his career, and yet he’s still, as he points out, “bashing away.”

After reading Rebel City, I know why he’s made it as far as he has. Chris can fucking write. Not only does he have all the technical stuff down (very sparse description, clean easy-to-read writing, characters that pop off the page as soon as they’re introduced, gets to the point quickly in scenes) but this just feels like a movie when you read it.

One of the things I love, as a reader, is when I go into something with expectations, and those expectations are immediately turned on their head. Like when I see “Crime” as the genre, 9 out of 10 times I know we’re going to start in some restaurant (or bar, or club) with a bunch of “tough guys” (cops or thugs) talking “tough guy speak.” The restaurant will always be over-described, giving the first page wall-of-text ebola. We’ll then listen in on the tough-guy speak, only to realize by the second page that there’s no point to the scene other than for the writer to be able to write this dialogue – dialogue, mind you, that is 95% clichéd.

In Rebel City, we start with a black screen and a phone call. The discussion is quick and to the point. “Where the fuck are you, Seamus?” “Your flight landed four hours ago.” “Wasn’t on it.” “I didn’t hear that.” “I’ll come get you.”

Not only do we start unexpectedly. But we start with PURPOSE. The words coming out of the characters’ mouths actually MEAN something. A story is being presented. In the very first scene! That’s how you catch a reader’s attention.

And that’s how Rebel City opens. Jonjo, a former criminal who used to live in the small dirty city of Cork, has to go back there to pick up his derelict brother, Seamus. You see, Jonjo’s 7 year old son is dying. Seamus is the only kidney match for him. But Seamus is a wreck. He’s already missed half a dozen plane flights back here with various excuses, and somehow Jonjo knows that if he doesn’t get him now, he might never get him.

So back to Cork Jonjo flies, thinking he’ll just show up at his old house and there Seamus will be. Except it’s never that easy with Seamus. Instead of his brother, Jonjo runs into three thugs who rough him up, telling him he needs to give Seamus a message. They want Florenta back, whoever the fuck that is.

Jonjo then heads to his sister’s place, who he hasn’t seen in years, and she wants nothing to do with him ON TOP of not knowing where Seamus is. Jonjo realizes that if he’s going to find Seamus, he’s going to have to go back inside the grisly underworld he worked so hard to escape. He’s going to have to be Bad Jonjo again.

So then, in the spirit of The Equalizer and John Wick (“That dog was a dying gift from my wife!”), that’s exactly where Jonjo heads. He meets some old friends and makes some new ones (if “making new friends” includes being shot at, tied up, and tortured). The longer he looks for Seamus, the more he realizes his brother’s involved in some deep shit, the kind of shit where even if he finds him, there’s no guarantee they’re going to get out of this town alive. But Jonjo’s son takes precedence over everything. If there’s any chance of getting his brother, he’s going to take it.

It’s hard to read Rebel City and not marvel at the skill on display here, particularly the dialogue, which is something we don’t get to celebrate enough on the site. Chris keeps his dialogue short and to the point so it zings by, knows his characters well enough that each one sounds a little different, and gives each line a touch of salad dressing to elevate it above regular conversation.

And his description isn’t too shabby either. Chris never lingers, never over-describes, but adds just enough flavor to paint a picture.

You’re probably sensing from my tone that there’s a “but” coming. And there is. But there’s something that didn’t click here for me. And this is one of the most frustrating parts of my job. It’s kind of like being a music producer. You have a singer come in and they have an AMAZING voice. It fucking blows you away. Then later you pop in a song of theirs and the song is ho-hum. You still hear that amazing voice, but the song isn’t doing it for you.

I think my reservations are due, in part, to me hoping the script would go in another direction. I thought Jonjo was going to pick up the world’s shittiest brother, Seamus, and the two would have to navigate themselves out of the town. Cause to me, Seamus was the most interesting character in the screenplay. He’s this piece of shit who has the opportunity to save his own nephew, and yet he can’t fucking get on a plane with a ticket already bought and paid for. I wanted to know more about what made that guy tick. And I wanted to see that sibling relationship play out over the course of the movie.

But after 20 pages, I realized that Seamus was a plot device only. He exists only to get Jonjo there, which means Jonjo’s going to be doing this alone. And don’t get me wrong. There are still some nice moments. Hell, I think the Peg-Leg Pete Dominatrix scene (page 65 for those who want to jump straight to it) should go down in the annals of Amateur Friday history. That was some fun/hilarious/disturbing shit.

But a lot of the other conversations and scenes felt too familiar. Just like those singers who can knock a high note out of the park, Chris had a stranglehold on these characters and they all sounded wonderful. Still, the song wasn’t making me dance. If you’ve asked one low-rent punk where Seamus is, you’ve asked them all.

So if I were Chris, I’d embrace the absurdity of this world. Just like the Peg Leg Pete scene and, to a lesser extent, the Evelyn scene (I feel like we cut out of that scene before things could get good), you make this a cast of characters that are over-the-top and fucking weird. Each one moreso than the last. The further this journey goes on, the stranger it gets. Because, yeah, the Cunninghams were okay as a gang, but they were far from MEMORABLE. I want memorable.

Also, and keep in mind this is coming from a sci-fi geek, I thought the mystery government high-tech box thing should have played a much bigger part in the story. That was the first moment where I went, “Whoa, what the hell is Seamus involved in here?” There was finally some real mystery to the story. But as soon as it’s mentioned, it goes back into hibernation. I would’ve loved for that to arrive earlier and be a bigger part of the plot.

The way I see this is we’ve already seen the standard version of this movie. The thug underbelly English/Irish life. So what are you going to do to make your “thug underbelly English/Irish life movie” different? How do you make yours stand out? I say you do it by putting more crazy into these characters. I understand this changes the tone of the movie significantly, and if that’s not the movie you want to write, don’t write it just because I think you should. But that was my problem with the script. It felt too familiar.

Script link: Rebel City

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: It’s no secret that I believe opening scenes are the most important scenes in the script. They’re the scenes where you either hook the reader or lose them. So here’s a strategy for writing them. Whatever TYPE of movie you’re writing (genre plus concept) ask yourself, what’s the most likely opening scene for that kind of movie. For example, if you’re writing a Western, the most likely opening scene might be a duel in the middle of town. Then, write something COMPLETELY DIFFERENT FROM THAT. Just write something they aren’t expecting. Because if you can defy your reader’s expectations on the VERY FIRST PAGE, they’re going to trust you as a writer. They’re going to believe you can keep doing that over and over again.

In some ways, a script is like a computer game. You’re writing a bunch of code in the hopes of providing the end user with a seamless enjoyable experience. If you get a line of code wrong, you’ll see a small glitch in the game. Get a few lines wrong, the game gets “glitchy.” Get a lot of code wrong and the game becomes unplayable.

How do you fix the game? You troubleshoot. You figure out where the glitch is occurring, what the corresponding lines of code are, and you rewrite them until the glitch goes away. Screenwriting isn’t that different. If the solitary McCall from The Equalizer is singing karaoke, that’s a glitch. All it takes is one reader to note, “That doesn’t match up with how McCall acts for the rest of the screenplay.” This observation helps the writer make a simple fix. He drops the scene where McCall is singing karaoke. Problem solved.

Unfortunately, you don’t always have the advantage of feedback. It’s hard to get friends to read your script and give detailed notes. And forget about someone doing it twice on the same screenplay. They may not say, “I’d rather kill myself than read this a second time” but you can tell by their expressions that that’s exactly what they’re thinking. Therefore, script reads must be saved. They cannot be burned. So in the meantime, you’ll be your own troubleshooting your stuff. But lucky you. I’m here to help.

The first thing you want to do when troubleshooting a draft is to get some distance from it. The more time you can spare (1 month is preferable to 1 week), the better. Essential for good troubleshooting is objectivity. And you can’t have that if you just finished a two month rewrite. It’s impossible for you to see anything objectively at this point.

Once you’ve created enough distance, read your script. Now when you do this, don’t worry about technical things (your sluglines or your description). That’s not what’s important. What’s important with any script is how it makes the reader FEEL. If the reader is swept away by the material – if they’re riveted or excited or sad, these are all good things. What you’re trying to do when you read your script, is act as the reader. You’re gauging how it makes you FEEL.

There is one particular feeling you want to pay attention to above all others: Boredom. Boredom is the biggest baddest enemy to writing. Scripts can survive angry readers. Scripts can survive frustrated readers. But no script can survive a bored reader. So every time you feel bored, write it down. Write down your other feelings as well (anger, happiness, shock), but boredom should take a 10 multiple priority over the other stuff.

Now keep in mind, you’re not a true reader of your script, since you’ve already read it dozens of times yourself. There’s going to be some reader-fatigue every time your read your own stuff, making you an imperfect test subject. But generally speaking, you should trust your feelings. If something feels boring or stupid to you, it’ll probably feel boring or stupid to others.

Once you’ve done this, look through your notes, and find the 4-5 biggest reactions you had. Like if a 20 page chunk was boring, that’s important. If you hated a character, that’s important. If a plot point or a plot twist felt really stupid to you, that’s important. We pick the five biggest reactions because we don’t want to be overwhelmed. You don’t want to try and fix every little thing yet. Besides, when you start fixing the big things, you’ll notice that a lot of the smaller things will correct themselves.

Now here comes the toughest part of troubleshooting. Once you’ve identified that a section of your script is boring, you need to figure out why. And why isn’t always clear. For example, let’s say Frank is writing a Die Hard-like movie that takes place on an oil tanker. Somewhere around the midpoint, Frank realizes that he’s bored with his script. The story is lifeless. What’s wrong?

I might read Frank’s “Die Tanker Die” and notice that at the midpoint, there’s a big four-scene chunk, 10 pages in total, of Frank’s hero, McChucker Doogan, talking about his backstory to his French love interest, Nadine Steauxpede. All four scenes are essentially saying the same thing. McChucker lost his family in a fire and he’s depressed about it. I might then tell Frank to combine all four of those scenes into a single one (or tell him to get rid of them completely). Instantly, the pace picks up, and all of a sudden the midpoint isn’t dragging anymore.

But it’s typically not that easy. Usually, a script issue is due to choices made long before the problematic scene (or sequence) was written. To figure our where the problem originated requires you to be a bit of a detective. And you don’t have to be an expert in screenwriting to crack the case. You just have to be perceptive. So let’s get back to that midpoint of Die Tanker Die. The new scene where we realize we’re bored is when McChucker’s hiding in a cabinet in the mess hall to evade the villain, Crooks Caravelli.

Why are you bored? This should be one of the most exciting scenes in the script! McChucker is inches away from being discovered by Crooks!

Look deeper into the scene. Instead of focusing on your general feeling of boredom, ask yourself, “What specifically is making me bored?” I don’t mean in “screenwriting-speak.” Speak plainly. What’s making you bored? You might realize after awhile that, “You know what? I don’t really like McChucker in this scene.” Okay, now we’re on to something. Just like a good detective, keep asking questions. Why don’t you like McChucker in this scene? Think hard. After a few minutes, you realize that it’s because McChucker’s hiding. But it’s not just that. It’s because so far, that’s all McChucker’s been doing throughout the script – is hiding. Unlike John McClane from Die Hard, who goes out there and actively kills the terrorists, McChucker is a hide-o-holic. He’s an inactive hero. Oh my god, you realize. No wonder I don’t like McChucker. He’s a wimp!

Now you have your first directive on the rewrite – Rewrite McChucker’s character. Make him more active. Make him braver. What’s important to note here, is that the scene where you realized you were bored wasn’t the reason you were bored. You were bored because of choices you made a long time ago – in the design of McChucker’s character.

But let’s say McChucker wasn’t the problem. Heck, McChucker’s your favorite part of the script! What then? Here’s something that might help. Try to locate that exact moment when you became bored. What was the exact scene that did it in for you? Treat it like a murder mystery. Look for the clues to solve the murder.

Say for instance the scene that really did you in was when Crooks Caravelli went on a three page monologue to his cronies about the parallels of their plight to the Greek Gods. Something bothered you about that scene but what was it?? Was the monologue badly written? Not really. Then it hits you. Why does Crooks have so much time to ramble on for three pages??? Shouldn’t he be, you know, enacting his plan?? Aha, you realize. If he’s got all that time, it means he’s not in a hurry. If he’s not in a hurry, then three’s not enough urgency in the story. That’s the problem.

So you go back to the drawing board and you add a plot point where the coast guard is on their way to the oil tanker. They’ll be there in 30 minutes. That’s how long Crooks has to finish his plan. Under this new setup, the writer realizes Crooks doesn’t have time to spout out empty 3-page monologues because he needs every second he’s got to complete his plan. Problem solved.

It’s important to remember that there’s never any ONE WAY to solve a problem. I could look at this same problem and come up with a completely different solution. For example, maybe McChucker sneaks into the bridge when Crooks isn’t there and notices that they’re heading towards a small unidentified body of land, land that shouldn’t be there. Before McChucker can find out more, Crooks comes back, and McChucker has to sneak out. We may not have the urgency of the Coast Guard on our tail in this version, but we now have some good old fashioned suspense driving the story. What’s this mysterious body of land?? Why are they going there??

Keep in mind that extended feelings of boredom (like beyond 20 pages) are indicative of much deeper problems that are usually due to one of three things: concept, structure, or character. If your concept is boring (2 guys fishing on a Sunday afternoon), it’s going to be hard for even the best writers to find 2 hours of drama in it. Make sure you have a concept that’s constantly putting your characters in trouble, is constantly forcing them to act.

If concept’s not a problem and large swaths of script are still boring, check your GSU. Make sure your hero and villain always have a goal, that there are high stakes attached, and that there’s a sense of urgency behind the objective. It’s fine if the goal keeps changing as long as it continues to meet the GSU criteria (every new goal is coupled with stakes and urgency – or the previous stakes and urgency are still in play).

If your structure is fine, ask yourself if your characters are interesting. Do they have compelling personalities? Are they fighting something inside of themselves (a flaw, a vice, good vs. evil). Are they fighting something with another character (can this marriage work, can this broken father-daughter relationship be salvaged, can we win this battle even though we have completely different opinions on how to fight it). Are the characters unique? Are they likable? Are they unpredictable? A lot of times a plot isn’t working because the characters inside that plot are boring as shit.

You’ll find that if you fix the 5 biggest problems in your script, your script will instantly be better. But note that with these new changes come new ideas, new additions to your script. And therefore, after you make the changes, you’ll go right back to the troubleshooting stage again. Figure out the five biggest new problems in your new draft, come up with solutions, and write a new draft. You’ll keep doing this for however long your process is (for some people it’s 5 drafts, for others it’s 20), until you finally feel confident that the script is the best you can make it. Now, my friend, you can send your script out there for the world to see and hope all that hard work paid off. I’m betting it will have.

What about you guys? How do you trouble shoot your scripts?