Genre: Psychological drama. I think.

Premise (after reading): Unhappy with her life, a housewife visits a physicist who transforms the way she views the world – and her own mind.

About: Carson received an email the other morning proposing I, Miss Scriptshadow, review our very own Grendl’s script. I have the female perspective on my side, which Grendl insisted was crucial. I know nothing about this script and I barely know Grendl outside of occasionally hearing Carson say things like, “The psychoness continues” while reading comments. The only stipulation for this review was a promise not to represent Grendl in a sketched caricature. So, instead, I’m including a suggested image by Grendl himself.

Writer: Grendl

Detail: 118 pages

I honestly don’t know how to start.

Grendl, dearest Grendl, has chosen moi as the prime-time reviewer of yet another supposed masterpiece: Undertow. I remember very clearly my day of reckoning, as if it had wandered to me in a lucid dream…

Carson awoke with drowsy requests for a crepe breakfast, and the cat was agitated and restless, seemingly unaware of my impending call to glory. I grumbled about the day’s chores, and rolled out of bed to mix up a batch of my very best crepe batter, prepared for yet another amazing day.

Unsavory rap music now thrumming through the apartment, I suddenly heard from the bedroom a tentative, “Um, there’s an interesting email from Guess Who. And it involves you.”

The email itself was tame, still not without a touch of the Gren’s signature, eerie flair – the above-featured black and white photo of a woman basking in ocean water taunted us from beneath the text. Why? We don’t know. We probably never will. I suspect it represents an ‘undertow’ of some nature. Either way, the woman looks to be having a grand time. I hope she’s not drowning. But, knowing Grendl, she’s probably already dead.

We start quietly with Veronica, a bored housewife, meeting her artist ex-lover Dean in a cafe as they discuss the probability that Veronica’s husband Eric is cheating with a redhead: a hair has been found plucked from his pants zipper, and it certainly doesn’t belong to Veronica. That hair makes for light conversation, something one-and-done for Veronica, and we quickly move into discussion about Dean’s big art showing at the MET.

Dean concludes their meeting by mentioning psychiatrist-but-not-really, Dr. Michael Saeghardt, and how the darkness in his life has all but gone as a result of Michael’s ‘radical’ work. Intrigued, Veronica visits Michael later in a spooky building after deciding she is simply ‘not happy,’ only to be greeted by a scary-as-hell janitor and the implication that all is not what it appears.

In fact, Michael is a physicist, an expert on ‘slip streams’ or channels of mental energies that surge across our planet, accessible through levels and lucid dreamlike states of mind. Veronica must use the escape word to get out of the stream: “hand.” Once uttered, Veronica ‘wakes up’ and sees her own naked body suspended in a clear chamber. She runs out of the room to see a black and white cat, which melts into a psychedelic, zebra-striped concoction of goop that splashes every surface as it chases her from the building. She ‘wakes up’ again on a beach to see a man named Harrington (not his full name, mind you), and then a little boy, Kyle. Kyle pulls her into a WWII-style shoot-out with laughing Germans.

But, wait! Veronica’s now in a movie theater with an old high school flame. Then she’s on a game show set where the janitor, Haberdasher, brings out the living corpses of each ex-boyfriend from her past so we can gloss over their histories with Veronica. In real life (supposedly) Dean reveals he found his soulmate through one of these ‘experiences.’ Veronica hopes for the same, but it never really happens for her – she’s still stuck with Eric. We finally end up in a courtroom wherein it is suggested Veronica made everyone up, and is actually a serial killer hell-bent on forcing unsuspecting men to her delusional will. The cat makes another appearance here, by the way.

It is now Dean who ‘wakes up’ from this experience (his? hers? I don’t know!) and waltzes out to meet up with a beautiful blonde who’s lost her… cat. Is it black and white, he asks? Nope. It’s gray.

Fade. Out.

I didn’t know how to start this review, and I certainly don’t know how to follow up a summary like that. I have never read anything so trippy in my life, which is really saying something since I delight in trippy. It’s what turned me on to film, the capacity for exploratory visuals, and worlds. Scenarios otherwise impossible and laughable in real life.

Yet, Undertow is perhaps exploratory to a fault.

While the dialogue is at times full of gems and the imaginative elements are unparalleled, everything just drags on and on. Conversations that could’ve ended in two pages instead last ten. Nothing connected for me even when it seemed to be laid out – the cat meant something, right? There was also a special ring, like an Inception token, to discern ‘slip streams’ and real life. Again, whether it really meant anything, or even connected as a common thread, is lost on me.

Grendl is truly tapped into the visual complexities of such an unusual world, such unusual circumstances. But that’s where the logic stops for me, and the confusing barrage of a dream world gone haywire, starts.

The biggest problem I noticed after really getting into the story was tonal inconsistency. I told Carson after getting through the first fifteen pages that I was getting a Blue Jasmine vibe: Privileged ‘bitchy’ woman is perpetually unhappy.

Then it got weird, with naked bodies in chambers tied to a ‘true’ physical world – okay, that’s the Matrix. Right?

Then, slip stream ‘levels’ and hypnotized dream sequences. That sounds a hell of a lot like Inception.

The rest is a psychotic Alice in Wonderland, if Alice were to face all her ex-boyfriends.

Reality-bending scripts are incredibly difficult to make work – not only does there need to be a clear establishment of rules and boundaries, but we need to have a little fun with it, too. Then it needs to service a plot that makes sense, and vice versa. It can’t be whatever just because we say it is. It can’t be entropic just because a physicist in the script explained it all away as free-flowing energy. Reality needs to be reality, and dream worlds need to be dream worlds. There has to be that distinction no matter what. I’m sure there were plot twists I missed because of subtle reality-dream-world mingling, and that’s the kind of movie I don’t want to watch in my free time. This is, without a doubt, a script from Shane Carruth’s wet dreams.

Carson once described the proportionate work required in reading a specific script as the ‘burden of investment’: When a script is aesthetically dense, too difficult to read in one sitting, mapped out so chaotically it gives you a migraine, etc., then there is a certain ‘investment’ you make as a reader in order to understand the script in its entirety. The ‘burden’ part is simply the taxation of mental energy. Undertow maintained a HUGE burden of investment. I didn’t know which way was up or down after I got to fade out, and I’m not sure I wanted to know. My head was spinning. It’s good to make a reader think about your words after they’ve closed your script, but this was the sort of thinking that’s driven normally sane people to suicide.

The hardest part of this review is knowing deep in my gut that this was a laborious passion piece, a work Grendl perhaps holds very close to that Grinch-y heart of his. Undertow is not without intellect. It is not without observing human ills. It is not without an inkling of theme, or characters with real problems, scenes built on wild abstraction.

I just don’t get it, that’s all.

Hell, not everyone’s understood my work – it happens to all of us writers, beholden to artistic liberty and all at once the ability to tap into a commercially-viable well of generic human experience. A rock and a hard place.

This script could be something quite fascinating – pare down the dialogue, make it clear what is reality and what is not. Focus on one major narrative, one smaller narrative. Kill your darlings. Assuming this is meant to be in salable condition one day, the goal would be to take the bizarre – the shades of Shane Carruth – and churn it into something the layman would go see on a Friday night.

And if it’s never to be sold? Then I suppose the above doesn’t matter. Do with it what you will. As for my ‘female perspective,’ I understand some of the underlying issues Veronica faces are perhaps meant to draw in a female audience, but I prefer to believe gender has nothing to do with it. If a character is great, it’s because of their actions. Not gender.

[x] what the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

WHAT I LEARNED: When dialogue scenes last too long, as many of these did, it’s usually because the writer isn’t tuned into the point of the scene (understands what each character in the scene is trying to achieve). If you know each character’s goal in the scene, you know exactly when they’ve achieved or failed, and therefore to end the scene and move on.

Genre: Comedy TV Pilot

Premise: After being held in an underground bunker for 15 years by a cult leader, a young woman attempts to navigate the complexities of New York City.

About: This is Tina Fey’s next big show for NBC. She wrote it with Robert Carlock, who wrote for Friends and 30 Rock. Due to the duo’s clout, they’ve gotten the coveted “straight to series” order, which seems to be happening more and more as the networks try to escape the expensive and laborious process of pilot season. Keeping it in the NBC family, the series will star “The Office” actress Ellie Kemper. Fey was the first ever female head writer on Saturday Night Live. She is also (and this is likely more interesting to me than all of you) a HUGE Star Wars fan. Yeah!

Writer: Tina Fey and Robert Carlock

Details: 28 pages (10/22/13 draft)

Despite the golden age of television becoming more and more golden, one of the genres that’s still stuck applying bronzer to itself is comedy. Comedies don’t have that “sexy” factor for some reason. They don’t have cancer-stricken meth dealing chemistry teachers looking into the camera and saying, “I am the danger.” They don’t have the coolest fucking zombie dispatcher in the universe telling his buddies, after being captured by cannibals, “They screwed with the wrong people.”

Since Modern Family came on the scene, there hasn’t been a single exciting comedy to talk about, and I think that’s because the TV comedy universe isn’t changing with the times. They haven’t traversed that same gap that the 1 hour drama has. Think about it. There are so many unique shows to pick from these days. Everyone is taking chances. But on the comedy front? What is there? Girls. Brooklyn Nine Nine maybe? Some people like “Louie” but I can’t watch it for more than 5 minutes without wanting to scrape my eyeballs out with a coat hanger.

Luckily we have Fey. I don’t like everything she does. But there’s an energy in her comedy that’s hard to match. Whether you like it or not, you know she’s having a blast doing it. Combined with a unique premise, which this has, I had high hopes for Tooken. Let’s see if they were met.

Kimmy Schmidt was snatched out of her front yard when she was 13 by a man named Richard Wayne Gary Wayne. Kimmy was the 4th of a group of women who would later become known to the world as the Indiana Mole Women.

The unfortunate four were kept in an underground bunker where they were told that the world above had been destroyed, taken over by robots, and that Richard Wayne Gary Wayne’s relationship with God was the only thing keeping them alive. That ended when the FBI showed up (and a nearby black man became famous for explaining to the world what happened via an auto-tuned Youtube video, which also happens to be the opening credits).

After being interviewed by Matt Lauer in New York, the girls prepare to head back to Indiana where they’ll start their lives. But Kimmy wants to do something bigger with herself and decides to stay in New York. She’s got a bunch of cash because of the Indiana Mole Women Fund, so she heads into a city with an 8th grade education and no idea what’s happened for the past 15 years.

She eventually meets Titus, a gay 30-something failed actor who’s sole goal in life is to make the cast for the Broadway musical, The Lion King. Short on money, Titus brings Kimmy in as a roommate, taking advantage of her complete financial ignorance.

On their first night together, he takes her out on the town, where she does a bunch of 90s dancing and attempts her first kiss, before Titus realizes that she’s one of the Mole Women. Feeling bad, he gives her her money back and tells her to get out of New York before it eats her up. She refuses to, saying that they’re going to take New York by storm and achieve their dreams together!

I gotta admit, breaking down half-hour comedy pilots is a little out of my comfort zone, but the more I read of Tooken, the more I realized writing is writing. You gotta come up with great characters. You gotta come up with interesting situations. And if it’s a comedy, you gotta make people laugh.

Sadly, I don’t know if Tooken achieved any of those.

The oldest staple in comedy is the fish out of water. It works every time. The only thing you have to do is come up with a fresh angle for it. And they did! I’ve never seen a Cult fish out of water comedy before. The problem was they didn’t fulfill the promise of that premise. It was like the fish was brought out of water, then placed in a New York City where it always rained. In other words, he was only slightly out of his element.

There were a few premise-fulfilling jokes, like the 90s dancing at the club and being excited about a tiny New York apartment because Kimmy was used to sleeping in a box. But other then that, the script was relegated to plot setup, which is the problem with these comedy pilots. You have to lay enough pipe for a hundred episodes and do it in just 22 minutes. So I get that it’s hard. But you’ve got to figure it out! Comedy is cut-throat. If people don’t laugh during the first episode, they’re done! I was really excited about Super Fun Night when it came out because I love Rebel Wilson. But I knew after 10 minutes that it wasn’t working. I never watched another episode.

It’s a moment you hope you never encounter in a script. That beat where you know the thing isn’t working and it isn’t going to work. I was on the fence for awhile here, but when Titus showed up, I knew it was over.

It doesn’t matter if you’re writing a comedy, a thriller, a drama or a period piece. One thing you can NEVER do is write uninspired characters. And you definitely can’t mail in a KEY character. Titus being an over-the-top gay Latino struggling Broadway actor is something I’ve seen dozens of variations of already. It was too safe.

But it wasn’t just him as an individual. It was him combined with Kimmy. When you pair up your two main characters in a comedy, they’re supposed to make each other funnier! They’re supposed to complement or clash with each other in a way that brings out some humor.

There was no clashing or complementing here. Titus was just this normal slightly sketchy guy who liked to go out. How does that complement a woman in ANY sort of interesting way who spent the last 15 years in an underground bunker?

I would rather Kimmy met a semi-cute straight New Yorker who we see some potential romantic possibilities with later in the series. That’s TV comedy 101. Give us two people we want to see get together.

Or team her up with some jaded New York bitch who’s the complete opposite of Kimmy. Whereas Kimmy has this boundless gullible optimism and, because of her experience, desire to always smell the roses, this roommate is out of touch and completely dependent on the New York machine. At least then we have some conflict.

To add injury to insult, the funniest parts of Tooken all took place within the opening five pages. The autotuned opening credits. One of the girls wearing rusty braces. Another girl, who was still brainwashed, confused after the Matt Lauer interview (“I’m married to you now. I go with you?”). But from then on, sadly, it was Exposition Series Setup City.

Of course, comedy is one of the most fluid processes in the business. It’s always changing right up to the shooting as they keep refining the jokes. So you know they’re going to keep working on this. My worry is that it’s not the jokes here. There’s something wrong with the foundation. They’re not mining this premise enough, which is forcing them to find comedy in the wrong places. And with how important the Titus character is, his miscalculation could prove to be a show-killer. They need someone who’s better integrated into the story and the theme.

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Find your comedy in drama. One of the easiest places to find comedy ideas is through real life drama. Look at any dire or intense situation and ask yourself, “Is there a way to make this funny?” Fey and Carlock clearly got this idea from the Ariel Castro kidnappings. They asked themselves, what would it be like coming back to society after living in isolation for 15 years? They had to change the backstory so as not to make it offensive, but this comedy idea was birthed from about as tragic a situation as you’re going to find.

Genre: Comedy

Premise: A man and woman working for a black market organ delivery service try to deliver a heart to a client while being pursued by the woman’s insane female boss.

About: Nat Faxon & Jim Rash are plenty busy these days. The Academy Award winning duo (The Descendants) jump back and forth between writing and acting projects (you’ve seen Rash as the unforgettable Dean in the recently cancelled “Community”) and are coming off of the indie flick, “The Way Way Back.” Their newest project, The Heart, has Kristin Wiig attached, and seemed like a go movie until a couple of months ago, when Indian Paintbrush got nervous about the budget. From what I understand, the movie isn’t cancelled or anything. I think they’re just trying to figure out how to make it for cheaper.

Writers: Nat Faxon & Jim Rash

Details: 109 pages (February 24th, 2014 draft)

I don’t know what Kristin Wiig is doing. Ever since Bridesmaids, she’s chosen to be in all these tiny indie movies that go straight to Itunes. And look, I think going indie is fine. You develop some street cred. Show everyone that you’re about the art.

But those decisions only work if the movies are actually good. And none of Wiig’s have been. Friends with Kids. Girl Most Likely. Hateship Loveship.

Hateship Loveship???

Someone really made a movie called “Hateship Loveship?” And people allowed this to happen?

Part of the problem is that the roles Wiig’s been choosing aren’t very interesting. The whole point of going indie is to play characters that you wouldn’t be able to play otherwise. Stretch your acting muscles a little. Her characters have been one step above mumblecore – which is to say they’re invisible.

And that’s my biggest problem with The Heart. Our main character (or, co-main character), Lucy, is invisible, keeping her emotions and opinions inside for the most part. This is one of the trickiest things a writer can tackle, is creating a reserved main character. Reserved main characters don’t “pop” on the page. They get lost amongst the action paragraphs and the sluglines while any character with something to say overshadows them.

That’s why I loved Cake so much, another female-driven indie flick. Cake’s main character, the grieving, angry, says-what’s-on-her-mind Claire made her presence felt on every page. Lucy keeps her thoughts in check unless she feels something needs to be said. The thing is, if that person isn’t active or constantly making choices that are disturbing the story, they just become the “boring character who doesn’t talk.”

Oh, I haven’t actually told you what the plot of The Heart is, have I?

So this woman, Lucy, has a grandmother who needs special care. So she needs money. Her current job, which entails delivering equipment for Chuck E. Cheese type establishments, isn’t exactly satisfying, particularly because her psycho boss, Dawn, is currently trying to prostitute her to clean up a bad business transaction.

So when Joe comes around, a courier for an illegal organ trade operation, and offers her ten grand to help him deliver a heart to Florida, she doesn’t have a choice. She has to take it. Of course, Lucy thinks this is all above the board. So when the only stipulation is that they use her van, she doesn’t think much of it.

However, when shit starts going south, Joe’s failure to mention the “illegal” part of his job comes out quickly. But Lucy isn’t exactly an innocent party here. She quit work without telling her boss. And she didn’t deliver the box of stuffed animals she was supposed to deliver. And those stuffed animals just happen to be packed with COCAINE because Dawn – it turns out – is running more than just a Chuck E. Cheese product delivery service.

That sends Dawn on their trail, who believes Lucy stole the cocaine on purpose. When she then finds out about this heart though, a heart that’s worth half a million dollars to its recipient, Dawn decides that she’ll be taking that heart and upping the delivery price. Throw in Joe’s criminal boss and our angry heart recipient (who’s a Pecan Roll Restaurant magnate), and pretty soon everyone’s trying to get their hands on this heart before it stops beating.

The Heart starts off really clunky, as the script strains to introduce all of our characters. Beware ye, the screenwriter, of the hero introduction scene. This is the scene where you need to tell us who our main character is. If said character is afraid of commitment, you want to open with a scene where they break up with a girlfriend because things are moving along “too quickly.”

Good screenwriters know this, and therefore spend a lot of time trying to perfect this introductory scene so the audience knows exactly who’s taking them through the story. Here’s the problem though. We writers can get TOO wrapped up in these scenes. We’re working so hard to sell the character, we fail to notice that the scene is starting to feel like a great big advertisement for our main character instead of, you know, a seamless piece of a giant puzzle.

Lucy’s introductory scene, where she’s trying to get a kid off one of the machines so she can re-stock it, feels too “set-up-y.” You can feel the writers underneath the scene “making sure” that the character is coming off the way they need her to. And the irony is that when you do this – when you spend more time on this scene than any other scene in the script to make sure it’s right – it ends up feeling the least natural of them all.

Here’s the solution. Whenever you write this scene (or really ANY scene that requires you to stuff a lot of shit in it – like exposition), take an “entertainment pass” on the scene. In other words, don’t read the scene seeing if you were able to slip in that one key character trait. Or see if you accurately portrayed their flaw. Just read the scene to see if it entertains you. Does the scene work on its own, independent of any of the things you’re trying to sneak in there?

Because here’s the shitty thing about writing. I know when a writer is trying to do something clever – like slip some exposition into a line of dialogue. And I commend them when they do it well! But the audience doesn’t know or care about that stuff. They don’t clap and say, “Yeah! Did you see the way that writer hid his exposition!? Wow!” All that stuff is invisible to them and supposed to be a given. All that matters to the audience is that they like the scene. So if anything feels stilted, they’re not going to enjoy it.

However, once The Heart gets on the road, it gets a lot better. I mean, for awhile there, I was like, “What were these guys thinking?” But I’ll tell you when I changed my mind. It’s when we find out that Lucy’s boss was secretly a coke-dealer using her business to deliver the drug. That was the first time I felt like the writers hadn’t just slapped this together.

That’s important. Because unless we encounter some unexpected plot points along the way in your story, the implication is a lazy effort. As soon as a reader senses laziness – that you didn’t work your ass off on each and every decision – they know that script is going nowhere fast. But yeah, after that moment happened, the script really started to take off and challenge the reader. I thought I knew where this was going, but instead, I was inundated with surprise after surprise.

Probably one of the best things these guys do is they have something going on with EVERY CHARACTER, even the smallest ones. And I think I know why. Faxon and Rash are character actors. They’re used to playing characters who were an afterthought to the writer. You can tell they use their writing to make sure that that never happens to an actor in one of their movies.

And what’s great about beefing up your secondary characters is that it often opens up new plot possibilities. For example, we have Gordy, our heart recipient. He has this whole backstory with his family and his restaurant franchise. That allowed Faxon and Rash to discover Gordy’s brother, who has his OWN backstory (he secretly likes Gordy’s wife and therefore wouldn’t mind if Gordy bit the dust). Because they went so far as to build up those backstories, it allowed them to come up with the brother trying to interfere in the heart transfer, as he becomes yet another player who goes after Joe and Lucy. In his case, he wants to destroy it.

So not only does it make the characters pop more. It invigorates the imagination and opens up more avenues for you to be creative.

As for the script as a whole, it’s got solid GSU (Goal – get the heart there, Stakes – both our heroes lives are on the line PLUS they both need the money badly, and urgency – the heart stops beating in 36 hours). Along with the unexpected twists and turns in the plot, it was a really fun read.

But the opening and the underwritten Lucy kept this from being anything more than a casual recommendation. Lucy is so restrained and so introverted for the majority of the time, combined with the fact that she’s not dictating any of the action (Joe is), that she’s not memorable enough. And the opening is trying to set up too much. We don’t get on the road until page 35, and I think that’s a direct result of too much information being jumbled into that first act.

So it was a cool script. It just needs to be tuned up in a couple of places.

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: In a big rowdy movie with lots of big personalities, the quietest character is usually going to get lost in the shuffle. So you have to think real hard about making that quiet character one of your protagonists. It’s not that a quiet protagonist can’t work. You’re just severely handicapping yourself when you use one. So think twice about it.

TV Pilot edition! Play nice.

Want to see new amateur scripts delivered to your email? Head over to the Contact page, e-mail us, and “Opt In” to the newsletter.

TITLE: Shrapnel

GENRE: Crime Drama

LOGLINE: An ambitious junkie and his severely traumatized war veteran sister, struggle with working for their manipulative crime boss father’s drug trafficking business.

WHY YOU SHOULD READ: The Sopranos meets Breaking Bad…. Could the bar be set any higher? Back in February when I uploaded Shrapnel to the Black List, it was ranked no. 2 overall on the monthly list. At its core, Shrapnel is about a brother and sister fighting their true identities trying to be people that they’re not in order to please those around them.Anyway, with the main goal of becoming a TV writer, the purpose of Shrapnel is to serve as a convincing staffing sample for similar genre/tone shows. It is not the most high concept of ideas and as a consequence I don’t expect to become the next Mickey Fisher with this project. I simply wrote the show that I want to watch. But concepts aside, the reason why we tune into our favourite shows each week is because of the characters, and hopefully the dried blood of my passion for the characters/story world is evident on the page.

TITLE: Jane

GENRE: N/A

LOGLINE: A woman posing as an IT security specialist lives a secret life as an assassin for hire.

WHY YOU SHOULD READ: I’m an aspiring screenwriter from New York. You should read JANE because it’s only 50 pages. It’s also very divisive. Two notable amateur Friday alums had this to say about it:

“Until the very, very end, the script has a few storylines that vie for attention but seem inconsequential to one another. Jane’s mission in the pilot doesn’t really give us further insight into her character despite her resourcefulness and how lethal she can be.”

and …

“I want to read it again tonight because, for the second time in a row now, I enjoyed it so much I came away with no constructive notes whatsoever. It’s making me feel like a fanboy.”

TITLE: Cartella

GENRE: Drama

LOGLINE: After her father dies in a shootout, a single mother finds herself to be the unexpected heir of a Mexican drug cartel.

WHY YOU SHOULD READ: Let me ask you something, AOW vets. When’s the last time you wrote an hour-long pilot in a week? I’m talking pitch to polished draft. Well, that’s the story behind “Cartella.” I was a finalist for the Television Academy Internship in the TV Writing Drama category, and had a week to submit an original script. For months I’d been searching for an opportunity to get this project off the ground, and this was it. After six grueling days, I busted out 49 pages of blood, sweat and tears. Even though I didn’t get the internship, I’m damn proud of the result.

I’ve been doing paid script coverage for almost a year now, while attending school full time as a screenwriting major. So when I say I know this pilot is good, I know it’s good. I wouldn’t have submitted it to the illustrious Scriptshadow if I didn’t believe it had a shot. This is my second original pilot and third TV project.

LOGLINE: Based on true events. At the beginning of World War 2, America scrambles to assemble the Office of Strategic Services, the wartime intelligence agency and predecessor of the CIA.

WHY YOU SHOULD READ: My writing partner and I are huge history buffs and we think the story of the OSS should be told, and would make an excellent hour long cabler. You should read this, because it has Nazis! But seriously, check out the opening Teaser and see if it hooks you to read more. We appreciate all your constructive criticism.

GENRE: Sci-fi, Action

LOGLINE: In the faraway future, a bitter hitman is sent aboard a sentient space station to kill his next target, but finds himself embroiled in a complex time loop among a series of psychopathic characters all hunting him down for his new found time machine.

WHY YOU SHOULD READ: This script has grubs the size of cars, cannibalistic priests, cults that worship machines, androids that kill, a civil war, an Abbé Faria, and finally… A John Titor. What more could you ask for?

Get Your Script Reviewed On Scriptshadow!: To submit your script for an Amateur Review, send in a PDF of your script, along with the title, genre, logline, and finally, something interesting about yourself and/or your script that you’d like us to post along with the script if reviewed. Use my submission address please: Carsonreeves3@gmail.com. Remember that your script will be posted. If you’re nervous about the effects of a bad review, feel free to use an alias name and/or title. It’s a good idea to resubmit every couple of weeks so your submission stays near the top.

Genre (from writer): Action/Adventure, Fantasy

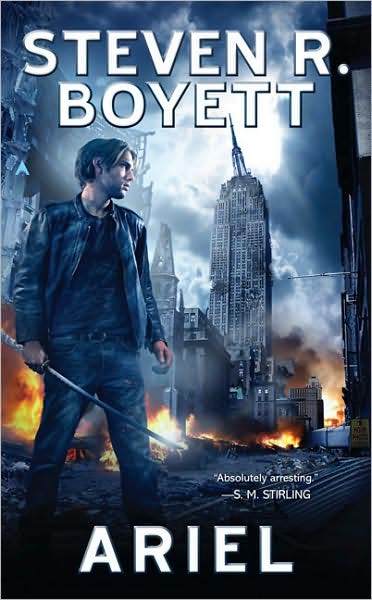

Premise (from writer): At the end of the world, young loner Pete Garey and his unicorn companion, Ariel, fight to survive in the chaos of the Change, where magic rules and they battle a dark sorcerer who covets the powers of her horn.

Why you should read (from writer): I have written a fantasy/adventure called “ARIEL” based on the 80′s cult classic young-adult novel by Steven R. Boyett. The script won Best Action/Adventure Screenplay in the Script Exposure Screenwriting Competition, and was chosen by Stephanie Palmer to be pitched from the stage at the AFM in November 2013. I first fell in love with this story when I was 14 years old. It really made an impression on me, (mythical creatures and post-apocalypse, whee!) and I always thought it would make a great movie. ARIEL seems to have a lingering effect on many of its fans. So, fast-forward to thirty years later: I optioned the rights and wrote the screenplay. I hope you and your readers will enjoy it too! — ARIEL is an edgy post-apocalyptic urban fantasy, an exciting road adventure, and a surprisingly funny story of courage and trust on Pete’s journey to becoming a man. — P.S. I had to laugh when I saw Friday’s newsletter and the presence of FIREWAKE on Amateur Offerings. I hope you will not be put off by the idea of TWO talking unicorn scripts – really, what are the odds?? That said, I have read FIREWAKE and the only similarity between the two is a talking unicorn character – they are very different stories.

Writer: Stacy Langton (based on the novel by Steven R. Boyett)

Details: 118 pages

Due to a mix-up in me being an idiot, I just discovered that today’s slated review, Black Autumn, was written by S.D., who’s other script (Primal) was reviewed just three weeks ago. I didn’t think it was fair to give up an amateur slot to someone who had just been reviewed, which sent me scrambling for a replacement. If you guys still want to get a Black Autumn review, let me know and I’ll figure out a day. But today feels like we must release someone new from the Matrix.

Where do you go for replacements at 11 o’clock on a Thursday night? I’ll tell you where. Unicorn Land!

Luckily for me, I had TWO unicorn scripts to choose from! It was a toss up, but I ended up going with Ariel. What did I hope to learn from this experience? Well, let me say this. Some writer (whose name I’m forgetting) once noted that if Harry Potter was the EXACT SAME STORY but written as a spec script called, “Limpy Ladderbottoms and the Candles of Pegasus,” it never would’ve sold. People only take chances on this “out there stuff” if it’s been proven in another medium first. Well, with Ariel being based on a book, I figured if it’s any good, we can give it a Potter platform!

18 year old Pete Garey is just a regular high school dude… until The Change comes. The Change is when the entire world stops working, all electricity, all machines, all batteries. Nobody knows why this happened. All they know is that they can’t cycle through Netflix movies for 30 minutes at a time anymore.

Oh, and that mythical creatures have invaded the earth!

While bumbling around, trying to figure out what’s going on, Pete meets Ariel, a unicorn. Ariel pulled a Harrison Ford so Pete must nurse her back to health, and along the way, they become friends! You may be asking how that can happen. It’s because Ariel can talk! She speaks in a little girl voice, and over time, Pete teaches her the entire English language so they can communicate.

As they head to the library to try and figure out what’s happening, Pete and Ariel feel the presence of a very powerful man, the Sorcerer, who they believe wants to find and kill Ariel so he can take Ariel’s horn! For those of you ignorants who know nothing about unicorns, a unicorn’s horn is said to be packed with magic. Therefore, they’re in high demand.

After the sorcerer hires some horn-men (get it? Instead of hit-men) to steal Ariel’s horn, it becomes clear that the only way they’re going to stop this meanie is to go mano et unicorno with the Sorcerer. Problem is, he’s in freaking New York, which is forever away. So they head down that way, picking up a samurai, a little boy, a horny woman, and a few other peeps, hoping to resolve this Sorcerer problem once and for all.

Hm.

I’m going to have a tough time with this one. First of all, we have to be fair here. This isn’t the kind of script that most people who visit this site are into. So right off the bat, Stacy’s got a tough sell. I’m sure if this was being reviewed on one of those Twilight sites, it’d be a whole different story.

But it does lead me to my first question. Who is the audience here? Because you’d think if we’re following talking unicorns, we’re looking at a 5-11 year old demographic. But the thing is, sex is a huge part of this script. One of the major threads is that only virgins can touch unicorns. And Pete is a virgin. That’s what allows Pete and Ariel to become so close.

That leads me to my next question. Why did it matter if only virgins could touch unicorns? Virgin or not, everybody was still able to see and talk to Ariel, so losing your virginity only deprived you of touch. You could still hang out, crack jokes about zebras, and get wasted on moonshine. Right?

Issue three was that I got the feeling there was a weird sexual thing going on between Ariel and Pete. I don’t know if that was on purpose or I was totally misreading it. But it made me feel the way the rope in gym did when you slid down it. Then you start imagining where everything goes and it’s just… well, it’s not church conversation, let’s just say that.

But let’s move past all that stuff. If I’m being honest, it’s hard for me to see what makes these magic worlds work or not. As crazy as a sexually frustrated talking unicorn sounds, is it any stranger than Harry Potter casting Griffensporf Level 5 spells on his ginger friend, turning him into an eagle spider? Not being the audience for this world, trying to gauge its logic is a hornless endeavor.

All I can do is comment on the story. Everything else being even, did the characters and the plot compel me to read on?

In a word, they did not.

First off, there was the double time-jump-forward in the opening ten pages (we jump a year forward after the opening scene, then jump another year forward after another scene). Not only is this clunky, it indicates a writer who doesn’t know where to begin their story. If we’re going to jump, just do it that one time. Two years ahead.

From there, there was a LOT of expositional dialogue with very little drama. It was a lot of characters talking about people they knew and how “you should meet this person” and “you can go to the library” and how “I’ve heard of this sorcerer,” and then “who is the sorcerer” and “what does he want” and “where are we going.”

Instead of scenes being used for dramatic purposes, they were used to talk about plot details plot details plot details. Characters talking about the plot is boring. Readers want drama!

For example, there was a scene in The Walking Dead (zombie apocalypse show) where Rick, our hero, shows up with his son and a friend at an abandoned house. He wants to rest and they want to go into town to look for food. So he takes a nap and they leave. While they’re out, some violent raiders come to the house, and Rick must hide. He knows his son and friend are coming back soon, and when they do, these men will surely kill them. But Rick can’t do anything about it. He’s trapped, unable to warn them without letting the raiders know he’s there. That’s drama! We have no idea how our characters are going to get out of this so we have to read on to find out! We don’t get a single crafty dramatic scene like that here.

There was also ZERO subtext going on under any of the scenes. Characters almost exclusively delivered two kinds of dialogue: They’d say exactly what they were thinking, or they would discuss plot exposition that set up later events.

This kind of thing becomes apparent once you run into a scene that actually does display subtext or conflict. And that’s what happened here. I noticed, all of a sudden, that I was drawn into a scene. It was when the new girl joins the group, and Ariel becomes jealous of her. Ariel tells Pete that she doesn’t trust her, but that’s not what she’s really saying. She’s saying, “This girl is trying to take my man. And I don’t like it.” They then kind of dance around that reality, without saying it out loud. That’s what I mean by subtext. But that was the only time it happened in the entire script.

Remember, the reader likes figuring things out. They enjoy trying to measure what two people are really saying while they’re talking. It’s like a little adventure. When you have two people saying exactly what they feel (“I love you.” “I love you too”), we don’t get to go on those adventures. So we become bored.

In addition to that, the goal was too muddy. Everybody talked about this Sorcerer guy, but I couldn’t figure out who he was or why he was important. People would say his name and then everyone would get jittery. So for a big portion of the script’s first half, we’re just talking about this guy but not doing anything about him.

Then, at some point, they say, “Okay, well, let’s go get him.” Which was good, because now our characters were actually moving forward. But I still didn’t know what the plan was. Was it to kill him? Talk to him? Strike a deal so he didn’t take Ariel’s horn? When the motivation for the main goal driving the story is muddy, the reader loses interest. How can someone be into something if they’re not sure why it’s happening? Look at Lord of the Rings. We know what Frodo is doing the whole time. He’s going to the volcano to destroy the ring. That’s always clear.

I think this script needed a clear goal right away. The motivation behind that goal needed to be strong. The scenes themselves needed less exposition, more drama, and more subtext. And it would’ve been nice if some of the rules had been clearer. Again, why does it matter if you can’t touch a unicorn if you can still see it and talk to it? Other than petting privileges being revoked, it’s the same thing.

On the plus side, the script was properly formatted. There was some imagination behind the world. And there was a certain charm to some of the characters. I think Stacy was up against a tough crowd. Even if this was the greatest talking unicorn movie ever made, you’d still have to drag me to the theater. That shows you just how high the standards were. I dearly hope this doesn’t hurt my chances of seeing a real unicorn someday, but this wasn’t for me.

Screenplay link: Ariel

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: For a dramatically potent scene, create a complicated situation where success is in doubt. That’s all that Walking Dead scene was.