Genre: TV Pilot – Horror

Premise: A vampire strain makes its way onto a flight from Germany to the United States, threatening to unleash a plague that could wipe out humanity.

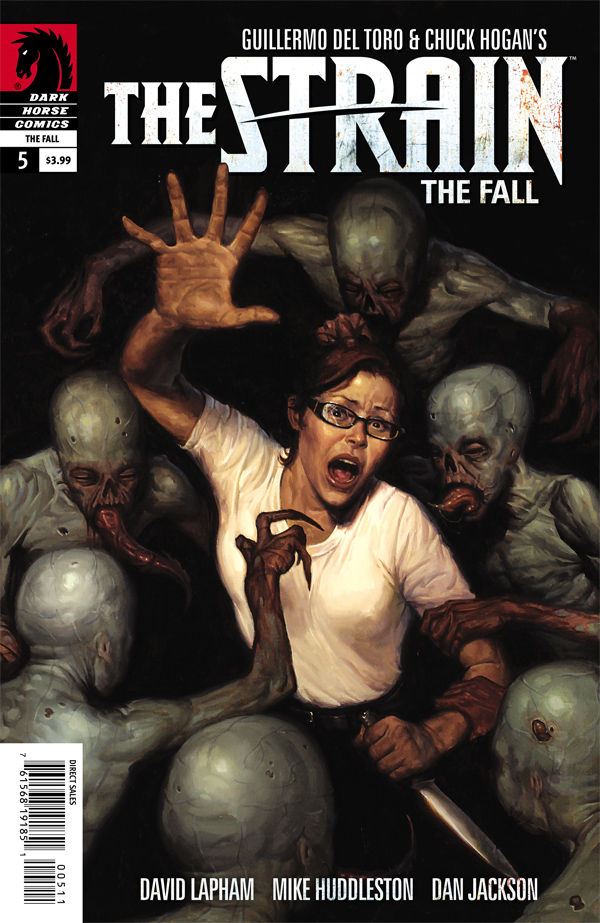

About: FX series “The Strain” is aiming to be the next big thing, FX’s answer to The Walking Dead. It’s got the pedigree to pull it off. With former Lost Exec Producer Carlton Cuse and Guillermo del Toro shepherding the show, geek blood is dripping off this thing by the bucket load. The Strain’s source material is a three-book trilogy co-authored by Del Toro and Chuck Hogan, whose 2004 book, Prince of Thieves, was turned into Ben Affleck’s, The Town. Man, self-publishing must be the way to go if even Del Toro has to do it to get something made!

Writers: Guillermo del Toro & Chuck Hogan

Details: 91 pages (June 26, 2013 draft – Production Draft).

I’ve been hearing some not-so-good things about The Strain. I’ve heard the source material isn’t so good. I’ve heard the script isn’t so good. But the talent involved gives one confidence. Del Toro’s working within the genre he’s most comfortable with (he felt a little out of sorts with Pacific Rim) and I’m a fan of novelist Chuck Hogan, who’s moving into screenwriting for the first time here. Plus, when you have low expectations, the only way to go is up.

40 year-old epidemiologist Ephraim Goodweather just got the call of his life. A plane just landed at JFK that’s “gone dark.” It’s sitting at the end of the runway without any signs of life. They need Ephraim to come in immediately and tell them what’s going on.

Problem is, Eph is in the middle of a court-appointed therapy session with his wife, who’s looking for any excuse to end their marriage. Eph having to leave in the middle of their appointment will likely be the last straw. But Eph can’t help it. In this case, he has to break the camel’s back.

But hey, it’s not like Eph’s running off to buy the latest Playstation. Lives are at risk here. Heck, this is a man who, if he screws up, an entire planet could die! So off to JFK he goes where he meets up with his sexy partner, Nora Martinez. The two board the plane to find that everyone’s dead. No signs of struggle. They’re all just sitting in their seats.

Then someone moves. Across the cabin, another body moves. 4 people have survived this mysterious phenomenon, and now Eph is hurrying to get them into quarantine. In the meantime, they trace some black light goo to the cargo bay, where there’s an old empty “cabinet” (aka, coffin) that has a lock ON THE INSIDE! Uh-oh.

Meanwhile, a crazy old man shows up begging Eph to burn the plane, the dead bodies, AND the living bodies, before “it” spreads. If doctors and scientists made decisions off the insane rantings of crazy old men, we probably wouldn’t have a planet to live on anymore. So they ignore him. Which is going to turn out to be a big mistake, methinks.

We hop back into New York where we meet Eldritch Palmer, the 3rd richest man in the world. Palmer is cavorting with pale people who don’t breathe, an indication that he’s up to something nasty. Indeed, he’s practically giddy with excitement about the news of the plane’s landing. Apparently, a long overdue event is about to occur. An event that will change the world forever.

The Strain is a competent pilot. That’s my problem with it. I want more than “competent.”

I mean we have all the ingredients for something cool, no doubt. We’ve got a mysterious plane landing where everyone is dead. We have implications of a demon/vampire unlike other iterations of vampires we’ve seen. We’ve got a conspiracy that starts with some of the richest men in the world.

While I was reading all this, I was thinking to myself, “I SHOULD be into this. So why aren’t I?”

Well, let’s start with the opening. A miscalculated opening is hard for a script to recover from. If readers are turned off immediately, they tend to keep that position throughout. Think about the last time you read a bad opening but ended up loving the script. It doesn’t happen often, does it?

The Strain’s opening wasn’t bad. But I’d seen it before. The pilot episode for Fringe was almost exactly the same, so right from the start, the story felt lazy.

From there, there were so many characters that there was no time to meet or get to know anybody. And the pilot was 30 pages longer than your average TV script. So it should’ve had plenty of time to set people up. The only person I got to know on any level was Dr. Ephraim. He was the only character who engaged in anything human, anything identifiable, via the therapy session he had with his wife.

One thing to remember is that TV is about characters. I get that the pilot has to set up the plot, but first and foremost, you have to hook us onto the people taking us through the story. Of the 20 characters introduced here, Ephraim is the only one I can visualize in my head. Everyone else was limited to a few lines of dialogue or a few adjectives of description.

One reason this may be the case? Ephraim was the only character who had to make a tough choice in the script. He’s in the middle of a marriage therapy session and he gets a call about the plane. There’s a potential disease outbreak on one side, and his marriage on the other. He’s gotta decide what’s more important. He picks the disease.

This isn’t just an example of a great way to introduce a character, but a reminder of how much more memorable someone is when they have to make a choice in a scene.

Outside of Ephraim, I’m not sure anyone here ever has a difficult choice to make. People tell other people what to do and they follow orders. No one finds themselves in a dilemma or a tough situation. It’s as if the plot is unfolding in raw form, before the writers came along and added drama to it.

Here’s what I mean. Take the scene where Eph and Nora have to check out the plane. As it’s written, they simply walk onto the plane, no problem. There’s no choice involved.

What if, instead, the airport Hazmat suits were damaged, left in a bad storage container. So Eph and Nora don’t have the proper protection to go inside. However, there are signs of life in the plane. If they don’t move fast, those people could die. Thus, a choice is presented. Go in with only threadbare protection, even though they’ll be at risk for exposure, or remain safe until better equipment comes, even though it probably means the remaining passengers will die.

And I’m not saying you have to write that scene. But you have to write “choice scenes” somewhere. You need choices. Or else there’s no drama.

In the Strain, everything’s laid out too perfectly. There aren’t enough obstacles making our characters’ lives difficult. Little troubles happen here and there (the coffin creature escapes) but it’s hard to tell how that affects things since we don’t understand what’s happening yet. In the end, I never felt that afraid or worried for anyone, which is strange when you consider that the fate of the world is at stake.

So, sadly, The Strain didn’t work for me. It’s not bad. But it left me wanting more. It needed more originality, better character setup, and more going wrong for the characters. Adding 5-6 more tough choices for people would’ve helped a lot.

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Repeat offender. Don’t use an adjective in your description, then quickly follow that with the same adjective in the dialogue. It reads lazy. So in The Strain, one of the characters is described as having “waxy” hands. Then, half a page later, one of the characters says, “Anything happens to her, I’ll find your waxy ass.” The repeat use of the word gives the text a lazy and uninspired feel.

What’s the quickest way to get a writer riled up? Bring up your writing process. There is nothing writers are more protective over, or feel more passionate about, than what is the proper way to write a script.

Go ahead, invite a few writers over and ask their opinion on outlining. Make sure to hide anything sharp beforehand. One writer will tell you outlining is essential and that there’s no possible way to write a good script without one, while the next will angrily defend the natural process of discovery that comes from free-form writing.

This kind of debate extends to structure, to theme, to characters. Writers always have strong opinions about these things and will fight other writers tooth and nail to prove that they’re right and you’re wrong.

If you ever find yourself in this situation and need to defuse it quickly, I have a solution. There is one thing that every single screenwriter in the world can agree on. That the Transformers movies are the worst written movies ever.

I don’t like to rail on films. I really don’t. But something about this franchise angers me. Transformers is the epitome of what’s wrong with the Hollywood system. The films are the poster-children for style over substance and a black eye for a trade that already struggles to be taken seriously.

How can you be proud to be a screenwriter when your peers are pushing this garbage onto the masses? Transformers is the leading generator of the all-to-familiar line: “I could’ve written something better than that.” It makes us all look like fools.

The crazy thing about all this? Transformers 4 is going to be the biggest movie of the year. If I’m a producer reading this entry, that’s exactly what I’m saying. “Yeah? Well if it’s so terrible, why is everyone going to see it?”

That’s a good question. And I don’t think we’re doing our jobs as screenwriters unless we’re trying to answer it. Because those producers are right. People are eating these movies up. And I don’t think it’s as simple as saying, “Yeah, that’s because people are idiots.”

There are idiots out there. But audiences vote for quality more often than they vote for crap. The Avengers, Toy Story 3, Avatar, The Dark Knight, were all #1 movies from years’ past. Those films were loved by both critics and audiences. But Transformers 4 is rolling by on a mere 17% Rotten Tomatoes score. So why is this happening? What is this film doing that’s making its awful script so insignificant?

Bonus Question: Is Shia better or worse off without the Transformers franchise?

Bonus Question: Is Shia better or worse off without the Transformers franchise?

Believe it or not, Transformers DOES do something right. You’ve heard it a million times from me but it never hurts to hear it again, since it’s the most crippling mistake a writer can make.

Write something that people will actually want to see.

Transformers is one of the coolest straight-up ideas ever. Note I didn’t say “concept.” There’s no concept here. This is an idea. But it’s such a great one, that it alone is responsible for 50% of the film’s success. Cars that turn into robots? Boys love cars. Boys love robots. Having the two transform into one-another? It’s genius. It’s the only toy idea that’s ever been announced as a movie where I’ve gone, “What took them so long?” The idea alone is a billion dollar idea.

This is important to note because a script is the sum of its parts. Assuming each part is given a number value from 1-10, your goal is to get as many high numbers for those parts as possible. If one part is a 2, that doesn’t necessarily mean your script is screwed. You could get a couple of 10s, and you’ve still got something pretty good. What nobody ever talks about, though, is that “idea” or “concept” is a weighted number. It’s more important than all the other numbers combined.

So when you go through the number values of Transformers’ parts, you get this: story = 0, characters = 3, dialogue = 1, structure = 2. You’d think the film couldn’t possibly survive numbers that low. Except when you get to “idea,” Transformers is a 100. Which means the sum of the parts is still high.

Another thing Transformers has going for it is it’s the ultimate “edgy” family movie. There aren’t too many movies that an entire family can go to and enjoy. Pixar films are the gold standard. But what if you have a 14 or 15 year old who thinks those movies are too sweet and saccharine? They’re not “cool” enough. Transformers is the perfect “next step up.” It’s edgier, yet still light enough that you can bring your 9 or 10 year old as well. I don’t have kids. But if I did, I could see my son wanting to see this movie and me shrugging my shoulders with a, “Hey, at least I get to see some awesome special effects.”

Here’s what I don’t understand though. Why CAN’T Transformers be a good story as well as a great action film? What’s preventing it from being both? Isn’t it a screenwriter’s job to take an idea and figure out a way to create a fully-fleshed out compelling story?

Look at Phil Lord and Chris Miller, the writers of The Lego Movie. That source material had WAY less to work with than Transformers, and they turned in a fun heart-warming action movie. What’s preventing Transformers from doing the same?

Besides the obvious (the director, Michael Bay, isn’t interested in the script), the reason they haven’t been able to do this is because of the mythology.

Mythology is the set of rules and backstory you create for your artificial worlds. It’s a crucial, often under-discussed, component in writing sci-fi or fantasy. If you don’t set up a set of rules for your world that makes sense, nothing you write on top of those rules will matter.

The mythology behind Transformers has never made sense. A group of alien robots come to earth to… turn into cars? Why?? It’s so silly, it’s ridiculous. By trying to stick with that mythology, the writers screwed themselves. Everything you build on top of “ridiculous” will be even more ridiculous! Screenplays need to be built on stable ground, not fault lines.

If you want to see mythology done right, watch The Matrix. There’s a lot of exposition in that movie. But after it’s all over, you understand why all the characters can do what they do. We know Neo can defy gravity but can’t breathe fire. The mythology has made that clear to us.

Once your mythology is set up, the next step is structure. Transformers fails spectacularly in this area as well. First off, each of its movies is well over 2 hours long. That alone tells you how little the writers (or producers and director) understand structure. The whole point of structure is to generate form, to give its subject a container. If you ignore it, your characters and story go off on numerous tangents.

Yesterday, Miss Scriptshadow confessed she’d been struggling with structure and wanted to know how I defined it. I explained it this way. Imagine Ferris Bueller’s Day Off. But all you have is Ferris and Cameron. You don’t have the “day off” part. You just have two characters who are friends.

An “unstructured” script would show these two going to class, eating lunch, maybe getting into trouble after school. It would be a series of unconnected scenes. “Structure” is when you add the “day off.” Now your characters have purpose, have a goal, have something to do. They must try to outwit the principal and get away with ditching school for a day. That simple addition of a container is what gives the script structure.

From there, you create little mini-movies (mini-goals) inside of the script to keep the story focused. First, Ferris must get Cameron on board for his plan. Then he must find a way to get his girlfriend out of school. Then they must have lunch at the best restaurant in town without getting caught. These little mini-movies keep everything contained and focused, and consequently, give the script momentum.

Nobody seems to know this in Transformers. Instead of clear focused goals, multiple characters have loads of unclear foggy goals, which continue to stack up on top of each other without clear resolutions. Characters do things without a point. There are long passages where we’re not sure why things are happening. The whole point of structuring something (typically through outlining – ahh! Sorry! I know you non-outliners hate that) is to prevent this. To give the story direction.

I know this isn’t a black and white issue. The industry will argue that any hit movie is good for the movie business. And studios will say that the Transformers’s on their slate are what allow them to make more challenging films like Black Swan and Silver Linings Playbook (although I wonder about this, since they were able to make these types of movies just fine well before Transformers came around). So I’m curious which side you come down on here.

Are there any screenwriting lessons to be learned from Transformers doing so well (you’re not allowed to say “That people are idiots)? And do you think these films are necessary for studios to make the more meaty stuff? Or is that BS?

Read this week’s Amateur Offerings collection and offer constructive criticism below, plus your vote for which script should be reviewed on Friday!

TITLE: ADAM

GENRE: Sci-fi Thriller

LOGLINE: A bio-mechanical man wakes with one memory: he must bring the woman he loves back to life. But his creator is on the hunt to catch his experiment, before the secret gets out.

WHY YOU SHOULD READ: A biologically engineered superhuman whose mind is half computer on the run through a post World War Three metropolis. Chased by cannibals, a cyborg with an identity crisis, a mysterious thin man, and corporate kingmakers. Helped only by an apathetic news anchor with hedonistic tendencies. — This is a story about the inevitable melding of man and machine, the digital world and the real one. The future of the internet and the human body. It questions how we will maintain our human identity in the face of exponential technological growth. — It’s Bourne+Blade Runner+Frankenstein with a hint of Hitchcock style thriller, Cronenberg and the Matrix.

TITLE: Haves and Have Nots

GENRE: Noir

LOGLINE: An investigative reporter returns home, delving into Las Vegas’ underground of addicts, prostitutes, and degenerates, to find her missing brother.

WHY YOU SHOULD READ: Carson writes that a lot of great specs are derived from the concept of taking a “seen-it-before” story and flipping it on its head. I took a noir, threw in a female protagonist and set it in Las Vegas. I integrated all of the set pieces of Vegas (casinos, strip clubs, pimps, vast expanses of emptiness) with the hallmarks of the noir genre: (tight, stylized dialogue, grittiness, femme fatales, a troubled hero with a cross to bear). I hope I did well.

TITLE: Tuesday’s Gone

GENRE: Dark comedy, meta-horror.

LOGLINE: Tuesday Wilson is a new mom. She spends her free time on Facebook. Uploading pics and bragging about her baby. When an ornery high school girl and her friends leave bad comments about said baby…she tracks each commenter down and takes their lives in funny, horrific ways. All the while a famous Hollywood actor and an old broken Detective are hot on her trail.

WHY YOU SHOULD READ: My name is Derek Williams. I had a pretty fucked up script called Goodbye Gene reviewed on AF early last year.

I’m now submitting my next script. It’s called Tuesday’s Gone. Nobody gets raped. No child molesters pop up. In the AF review Carson said, “the next thing this guy writes is probably going to get made. That’s what my gut is telling me.” Well…here it is. Let’s see how well you know your gut, sir.

This is a satire about “Facebook Moms.” Come on. We all know an annoying Facebook Mom.

TITLE: Big Bear

GENRE: Action/Thriller

LOGLINE: Two married elite special operatives infiltrate a southern California terrorist cell in order to thwart a major terrorist attack and ultimately take out Bin Laden’s successor– a man who is under increasing pressure to carry out a fresh act of headline-grabbing terror to cement himself as the new #1.

WHY YOU SHOULD READ: This script placed in the top 15% of the 2012 Nicholl Fellowship Screenwriting contest. (Somewhere between 720-1080 out of 7200 scripts!!) Considering that this script is far from a Nicholl-style script, I believe it fared pretty well. And since then, it’s been optioned, and undergone a few rewrites. BIG BEAR is an independent action movie. I personally wanted to focus more on the struggle between two married special operatives on the mission of their lives than blowing shit up. Bottom line: It’s different. I’d love to put the script out to your readers to see if it can be upgraded further.

~*COMEBACK SCRIPT*~

TITLE: THE HARVESTER

GENRE: Horror

LOGLINE: Murdered to advance the construction of an exclusive golf resort, a mountain man is resurrected by Death himself to take revenge as an undead killing machine.

WHY YOU SHOULD READ: I’m a lifelong horror fanatic and very much a product of the VHS generation. This is my sincere attempt at horror the way I lovingly remember it; gruesome and gory, but also imaginative, cinematic and, most importantly, FUN! THE HARVESTER is a high-concept, blood-soaked blast of old-school carnage with an ending so wild and explosive that it needs to be read to be believed. Hope you enjoy!

Get Your Script Reviewed On Scriptshadow!: To submit your script for an Amateur Review, send in a PDF of your script, along with the title, genre, logline, and finally, something interesting about yourself and/or your script that you’d like us to post along with the script if reviewed. Use my submission address please: Carsonreeves3@gmail.com. Remember that your script will be posted. If you’re nervous about the effects of a bad review, feel free to use an alias name and/or title. It’s a good idea to resubmit every couple of weeks so your submission stays near the top.

Genre (from writers) Historical Action

Premise (from writers): In 30 A.D., a charismatic stonemason bent on revenge leads a band of guerrilla rebels against the Roman occupation of his homeland.

Why You Should Read (from writers): This is the story that led up to the biggest trade in human record. It is Braveheart meets Gladiator, with characters on a collision course that splits history in two. Come for the battle, the intrigue, and the epic. Stay for the sacrifice, the betrayals, and the passion that drives a man to darkness. — As co-writers, we work from 3,000 miles apart. Yes, we have two of the WASPiest names imaginable. No, they’re not pen names. We’ve been polishing this script to a trim, accelerative tale that strengthens, weaves, and deepens with each choice our characters make. The ending is the most difficult we’ve ever worked on, but the feedback on the resolution has been powerful. We have to earn the effect we want a story to have, and with this script we aim to challenge, to provoke, but most of all…to entertain.

Writers: Parker Jamison & Paul Kimball

Details: 112 pages

Man, the last couple of days have been carraaaa-zy in the comments section. The Comments Post did not go over well with a lot of you. Miss Scriptshadow’s review caused a nuclear-sized meltdown in the Grendl-verse, and some manic derilect from 2011 topped it all off with a bunch of “Carson is evil” comments.

Today, however, it’s going to be all about the script. If you want to talk about other things, feel free to go back to those earlier posts. But I want today to be about the writing, specifically Barabbas. I’ve already read Barabbas once for a consult and I liked it with reservations. So I’m really glad you guys picked it as a healthy discussion should continue to strengthen the script even more.

The story is not without its challenges. It puts itself in some unenviable writing situations, which I’ll get to after the summary. I’m also interested to see what these guys have done with the latest draft and how much the script has improved. Let’s take a look.

“Barabbas” offers something whether you’re familiar with the story of the man or not. If you’re like me and had never heard of him, Barabbas plays out like a slow-burning quasi-mystery, pulling in familiar elements from religious history that eventually lead to a shocking finale.

If you do know Barabbas’s name, the script plays out like “Titanic.” You know where this will eventually end up, so you’re curious what’s going to happen to get us there.

Joshua Barabbas, 30, is a stone mason. Along with his younger brother David, the two build bridges and aqueducts for the Romans who, at the time, were occupying Jerusalem. When the Romans raid the Jews’ own temple to pay them their wages, David and Joshua have had enough, and rebel.

When their friend is erroneously chosen as the instigator of this rebellion and crucified, an angry Barabbas is persuaded by a local politician, the sinister Melech, to start a war. Using rage to guide his leadership, Barabbas and his fellow workers attack the Romans, but eventually flee to the mountains once outnumbered.

Realizing that there’s no turning back, Barabbas starts to grow a small army with the hopes of driving the Romans out of Jerusalem. But when Barabbas falls for the wife of a key ally in the city, he loses focus, and the rebellion begins to fall apart.

In a last ditch effort to recruit a huge army from the surrounding regions, Barabbas designs a plan to take down the Roman Regional Governor Pontius Pilate. (major spoilers) He ultimately fails, and his life hangs in the balance of the people themselves, when they must choose which of two men shall be set free, Barabbas or Jesus Christ.

I knew this weekend’s Amateur Offerings was going to be good because I’d read two of the scripts and knew both were solid (the other being “Reeds in Winter” about the infamous Donner Party, which ended up in some gnarly cannibalism). The rub? They were both period pieces, which are the hardest to get readers on board with. Therefore it was satisfying to see them both end up with the most votes, as it shows that readers still respect challenging material.

With that said, each script has its trouble spots. Assuming the reader sticks around long enough to get into the story, which is never a guarantee with period pieces, I was always worried about that darned Barabbas second act.

The problem is this – the second act is where countless scripts go to die. It’s hard as hell to keep it interesting even under the best of circumstances. In Barabbas’s second act, our army is relegated to a single location up in the mountains. Keeping a “swords and sandals” period piece lively when the main character and his army are relegated to one spot for 60 pages is as challenging a proposition as you’re going to find in screenwriting.

Compare that to Braveheart. The great thing about that film was that William Wallace kept moving across the country to bigger and bigger cities, so we got this sense of BUILDING as the story went on. That’s harder to do when characters are hiding in caves in the mountains, especially when you’re limited by history. Barabbas’s army couldn’t have gotten TOO big or else he would’ve been more well known in the history books. Barabbas’s one defining characteristic in the bible is that so little is known about him.

But my gut’s telling me we need to either get Barabbas off that mountain space at some point, grow his army bigger in some way, or find some other means to spice up the second act.

What if, for example, Barabbas had to go out on some recruiting trips into the surrounding cities? If we built up certain meetings with city leaders he would have to win over in order to receive their soldiers, that’d be one way to keep the story dynamic.

Getting him off the mountain to meet Jesus at some point would be interesting as well, but Parker told me he doesn’t want to physically see Jesus until that final scene, which I understand.

Another thing that bothered me during the initial read, and something I don’t think Parker and Paul have addressed yet, is the character of David, Joshua’s brother. Over the course of the script, David sees Jesus speak (we don’t see this) and starts to respond to his teachings. Whereas Barabbas wants war, David preaches forgiveness and peace.

The problem is that all of this happens too late and doesn’t have enough conviction. I was bothered, for instance, by a character named Thaddeus, who comes into the story late to aggressively preach Jesus’s philosophy. I couldn’t understand why this character wasn’t David. In order to get the maximum amount of conflict from a relationship, you need the two characters to be on opposite sides of the philosophical spectrum. David was tepid in his support of Jesus’s teachings until the very end. Let’s have this guy go out there, see Jesus speak, and let him be the one who comes back and starts aggressively converting the other soldiers. Now you have a direct conflict. Barabbas needs soldiers to take down Pontius and his own brother is turning those soldiers into pacifists. Isn’t that better than Random Thaddeus, who I met five minutes ago, who has no allegiance to anyone, converting these people?

One of the complaints about Barabbas during AOW week was dialogue. Most people said it was serviceable, but that serviceable isn’t good enough in a spec trying to stand out. And I’d agree with that. But fixing this is a lot easier said than done.

What I believe people are responding to here is the lack of “fun” in the dialogue. People always seemed to speak in a proper and serious way. “You still labor at the aqueduct?” “Every day. Why?” “I’ve heard that funds are running short. That Pontius Pilate needs extra coin to finish it.” “As long as the Romans pay, we work.” This is a conversation between two people who have secretly loved each other since childhood. You’d think they’d have a more relaxed and easy rapport, right?

But the biggest issue here is that almost EVERYBODY spoke like this or very similar to this. So the problem might not be “dialogue” so much as “variety in dialogue.” I always talk about creating “dialogue-friendly” characters. People who have fun with the language and say things others wouldn’t. It would be nice if a featured character here were dialogue-friendly. From there, look at every character and figure out ways to make them speak differently from everyone else.

Finally, I wanted more out of the ending. I think the problem here is that Parker and Paul see the sacrifice at the end as the climax. Which it is. But before we get there, we need to give the audience the climax they’ve been waiting for, the one we’ve been building up for 80 pages, which is an attack on Pontius Pilate.

Let’s see him and his army try to head Pontius off at the pass on his way to Jerusalem. Let’s see him almost kill Pontius. He ALMOST does it! But something at the last seconds prevents him from succeeding and he’s captured.

Then, since it’s now personal between him and Pontius, we can see Pontius, behind-the-scenes, preparing Barabbas so that he’ll be the one picked for crucifixion by the people. Pontius makes him extra dirty and nasty looking, in the hopes that he’ll be the one killed.

I know we’re playing with fire here, but it could be an ironically delightful ending to see that Pontius had a horse in the race and was hoping to snuff out Barabbas, which, of course, would’ve changed history. He’s visibly disappointed, then, when Jesus is chosen instead.

Whatever these guys choose to do, though, I trust them. Barabbas is not perfect, but it shows a lot of skill, and it shows two writers who are going to make a splash at some point if they stick with it. I don’t know if it’s going to be with this script because, again, the subject matter is challenging, it’s a unique sell, and there’s that whole second act issue that I’m not convinced is solvable. But I just like these guys as writers and hope to see more work from them in the future.

Script link: Barabbas

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Use specificity instead of generalizations when writing description. Today’s “What I learned” actually comes from Casper Chris, who I thought made a GREAT observation when he compared two action paragraphs from Barabbas and Braveheart during AOW. Here were the two he compared…

Barabbas:

Barabbas leads the charge. The rest of the stonemasons pour down on the patrol. Slashing, spearing, hacking. Barabbas fights like a barbarian, fearsome and brutal. Ammon slices through soldiers with precision. David is quick and athletic.

Braveheart:

He dodges obstacles in the narrow streets — chickens, carts, barrels. Soldiers pop up; the first he gallops straight over; the next he whacks forehand, like a polo player; the next chops down on his left side; every time he swings the broadsword, a man dies.

Notice the difference. Whereas the Barabbas text uses mostly general words to describe the action (“slashing, spearing, hacking” “fights like a barbarian” “quick and athletic”), Braveheart uses specific imagery. There are more nouns here and the verbs are used to highlight powerful actions (“chickens, carts, barrels” “soldiers pop up” “he gallops straight over”). It was a great reminder that we need to put specific imagery into the reader’s head so he can properly imagine what’s happening up on the screen.

Welcome to the 1st edition of “Comments of the Week” on Scriptshadow. This is where I turn it over to you guys, the readers of the site, to do my job for me! “Best Comments” will not be a weekly thing, but rather something that pops up every now and then. If you want to be included, offer a strong take on an interesting topic. You guys often say things way more profound than me, so it’s only natural that we share these comments with the masses.

We’ll start with a great exchange after my review of the TV Pilot, Rush, courtesy and Gyad and Larry.

I have to say I’m getting burnt out on morally dubious protagonists. Sure, as script readers the “edgy” character appeals to our jaded palates but there have been so many of late that seeing a morally upstanding hero in a (non-network) series is becoming unusual.

This is a good point. I’ve been telling people that this kind of character is the way to go when writing a television series. But are we becoming so inundated with them that they’re losing their luster? Either way, I liked what commenter Larry had to say about it…

Agreed. What makes shows like Breaking Bad or Walking Dead awesome is that people do bad things but for GOOD/honorable reasons. This Rush guy seems just to be out to make some cash.

I hadn’t thought of that it that way but it makes sense. Morally ambiguous or not, we like these characters better if they’re doing these bad things for good reasons. Though it should be noted that Walter White stops doing what he does for good reasons in the final two seasons. Then again, because we took that long journey with him, we still wanted to see him succeed, or maybe come back from the edge.

This leads us to our next observation from Adam Parker, a response to my review of The Martian. The discussion had to do with Mark Whatney being a flat character and did we care about his journey enough to stick around for the whole ordeal? Some commenters said we did because Mark’ life was on the line. To which Adam responded…

The main conflict (or narrative question) can NEVER be “Will the Main Character survive?” the answer is always YES.

While Adam’s statement isn’t true in all respects, the point he makes is a good one. 99% of the time, the main character will survive. So it isn’t enough to ONLY hinge your movie on that question. Instead, you should try and ask a deeper question. Like with Gravity (as some other commenters brought up), the question wasn’t only “Will she survive?” it was “Did she want to survive?” She’d lost her daughter and she was struggling with whether life was worth living. You’re always trying to find that deeper question to explore to give your story that added layer of depth.

Moving on to something way bigger in scope is the question of, what the hell is going on with the spec market? I honestly think Transcendence really fucked us. That was going to be the one original property that had a chance to stand up against these monster IPs. When it tanked, it scared the crap out of everyone. I still think the spec market will come back, but let’s not forget that there are new options being presented to writers. You have the ability to write something and publish it within 30 minutes on Amazon. That’s huge. Here’s Logline Villain’s thoughts on the matter…

Instead of adapting another’s book, one might consider writing his/her own book and then holding firm on scribing the adaption (e.g., Gillian Flynn – “Gone Girl”). Granted, the work has to be scooped up first, but that is always the requisite for breaking through in any writing platform.

Has it reached a point where penning a novel may be the aspiring screenwriter’s best opportunity to break through with ORIGINAL material? With self-publishing, the ‘net and Amazon, there are more avenues than ever to promote one’s novel – it worked out swimmingly in the case of today’s featured “The Martian“…

I suspect a market correction will come one day – where spec scripts are again in vogue – but is it worth crossing one’s fingers until then? I know, if it’s the next Chinatown, it will sell as a spec…

In the meantime, what’s more important? The end result or how one gets to the end result…

The egg must figure out a way to become a chicken. And the lion’s share of these adaptations are going to established chickens…

There’s more than one way to skin a cat.

But before you close Final Draft forever, heed PmLove’s response…

I remain unconvinced. We can spend our lives chasing our tails over a breakout novel or script, either way it’s still tough to be the goose that lays the golden egg. There are so many $0.99 self-published books it’s hard to see the wood for the trees – I’d want more compelling evidence to say that self-publishing a novel is more likely to lead to a screenwriting breakout for original ideas. I’d say you might be barking up the wrong tree.

A great point. The grass is always greener on the other side. I’m sure there are writers over on NovelShadow saying the same thing. “There are so many books out these days, it’s getting harder and harder to stand out. I should just go to Hollywood and write a screenplay. All the movies there suck. I know I could do better than them.”

We’re going to finish with a couple of thoughts from Nicholas J, who always seems to have well-thought-out takes on the days’ article. The first is a reminder of the importance of concept, which is easy to forget.

I think there’s a very good argument to be made that concept trumps all. Given the choice between a great script with a ‘meh’ concept and an average script with a great concept, I have to think the majority of people who make movies will take the high concept. You can improve the execution of a great concept, but you can’t really infuse a great concept into a script that doesn’t have one.

That last sentence is the golden nugget. I was just dealing with this recently with a writer. We were doing everything in our power to give his logline more kick. But the reality was, his story wasn’t unique enough to create a compelling logline. That’s not to say the script won’t be great, it just makes things harder for him since he’ll get less script reads. This is why I tell people, if you have a choice, give us a hook in your concept, something you can write a logline around. Because once you dedicate yourself to something and the months (or years) go by, you’re less inclined to give up on it, even if you know your concept is weak. You have too much invested to move on. All of that could’ve been avoided with a simple two-minute decision at the beginning of the process: “Is this a good concept?”

And here’s Nicholas’s negative take on last Thursday’s article about “Exceptional Elements.”

It’s not that the average writers have accepted mediocrity, it’s that they are average writers.

That’s kind of like saying a college quarterback that never reaches the NFL is worse than Peyton Manning because he’s accepted mediocrity. Sure, Manning worked hard to get where he is, but so did the other guy. Manning just has the better combination of skills necessary to succeed. Manning is just better.

It’s the same thing with writing. There’s a reason that a microscopic percentage of aspiring screenwriters find worthwhile success. Writing something great takes an exceptional combination of unnatural skills. But the most important skill to have is creativity.

Creativity can’t be learned. Have you ever played a board game like Balderdash or one where you write photo captions? Some people, no matter how hard they try, are never able to come up with something good. Their minds just don’t work that way. Chances are their minds are better suited for something else like mathematics or memorization. I have a friend who is a genius when it comes to how things work. He’ll take one look at an HVAC system, tell you what makes it inefficient, and what possibly could be done to improve it. (Though I have no idea if he’s right or not since I don’t understand a word of it.) But ask him to look at a photo and come up with a funny caption and his brain short circuits.

This is what results so often in those average scripts. It doesn’t take a creative mind to love movies. And it doesn’t take a creative mind to love writing. So a lot of people attempt to write movies despite not having an ounce of creativity. This is why you see so many knockoffs in the amateur pile.

The writer loves mafia movies so they think, “I’m going to write a mafia movie!” They sit down to write and think of all the mafia movies that they love. They pull elements from each, whether consciously or not, and end up writing a paint-by-numbers version of Goodfellas. They’ve failed to put any actual creativity into it, and yet they don’t even realize it.

On the other end, you have those crazy scripts that don’t make a lick of sense. I mean, it’s great that you came up with a movie idea about a dog that goes to shark heaven, but that idea is fucking stupid. You see this a lot with amateur scripts where the writer throws crazy elements at the page, thinking it makes their script original and awesome, but it just ends up as a confusing mess to everybody that isn’t the writer. This is a result of the writer forcing creativity when they have none, or having a lot of creativity but not knowing how to harness it into something sensible.

So not only do you have to be creative, but you have to find the right balance of your creativity. You have to know how to fit it into a genre, or at least something that people will understand and want to see. You have to know how to dial it back and amp it up when necessary. You have to give it structure.

And I’m sure there are plenty of pro writers out there that don’t have much creativity either. But chances are they won’t continue to be successful for long, and may find other opportunities in the business that suit them better. And once you’re in the business, as we all know, you don’t have to write the next ETERNAL SUNSHINE to make a sale. But if you’re still looking to break in, you better be on your A-game, and your A-game better come with a rollercoaster of balanced creativity. Nobody breaks in with paint-by-numbers Mafia Movie #253.

Or, you could know somebody important. That works too.

What do you guys think? Do you agree with Nicholas? This comment led to others asking, “How do you know if you’re exceptional or not?” Doesn’t everyone think they’re exceptional? Isn’t that why so many bad scripts get submitted everywhere? I guess by breaking things down into manageable chunks, I was hoping it would be easier for writers to see what their strengths and weaknesses were. But if you’re new to the craft, it’s hard to have any reference for what “exceptional” is. You don’t know what you don’t know. So I’ll leave it up to you guys. How does one know if their work is any good outside of the obvious (impartial feedback)? If you give us a good answer, you might find yourself featured on the next “Comments of the Week!”