Search Results for: star wars week

Genre: Sci-Fi Comedy

Premise: Set in the future, a married couple trying to join an exclusive orbiting community (above earth), is forced to adopt a 13 year old girl due to the community’s “families only” policy. Little do the girl and the community know, the couple’s intentions aren’t so kosher.

About: Every Friday, I review a script from the readers of the site. If you’re interested in submitting your script for an Amateur Review, send it in PDF form, along with your title, genre, logline, and why I should read your script to Carsonreeves3@gmail.com. Keep in mind your script will be posted in the review (feel free to keep your identity and script title private by providing an alias and fake title).

Writer: John Sweden

Details: 97 pages (This is an early draft of the script. The situations, characters, and plot may change significantly by the time the film is released. This is not a definitive statement about the project, but rather an analysis of this unique draft as it pertains to the craft of screenwriting).

I’ve been hearing some strongly opinionated rumblings about this script all week. I just want everyone to remember, this isn’t Trajent Future we’re talking about here. We don’t have the writer telling everyone they’re idiots for not liking his script (or at least, not yet). My assessment of John Sweden is that he’s a nice guy, someone interested in the craft, but whose proximity to screenwriting may not be as close as the rest of us. We all started somewhere. We all know what those early scripts of ours looked like, so don’t be mean here. Be critical, but don’t be mean. Now, having said that, I have to call it like I see it, so to Mr. Sweden, take a seat. There’s going to be some tough love in this breakdown. Try to take it constructively. In the end, it’s about learning from your mistakes and becoming a better screenwriter the next time around. :)

The first hint that something’s off here comes in that DAD and MOM, the main characters in Orbitals are referred to in quotes throughout the screenplay. So they’re “DAD” and “MOM.” Anyway, “Dad” and “Mom” are obsessed with sex. In fact, the movie starts out with them trying to make a sex tape. I’m not sure what this has to do with the story, other than maybe being a viral offshoot of Monday’s script review, but it’s a pretty darn strange way to open a script, I’ll tell you that.

Anyway, the other thing “Dad” and “Mom” do is swear a lot. Fuck this and fuck that and fuck fuck fuck and lots of use of the word fuck. I did a word count and there are over 150 uses of the word fuck. That’s almost 2 per page!

Now I’m a little confused about this next part, but I think “Dad” and “Mom” work for the military. And they need to get up to this orbiting community to execute a top secret plan. Unfortunately, the “Orbitals” don’t allow you up there unless you’re a full family, with children and such. So “Dad” and “Mom” decide to adopt a teenager.

Luckily for us, “Teenager” has a real name. Aubrey. And Aubrey, just like her new parents, likes to use the word “fuck” a lot. Now for reasons that aren’t entirely clear to me, once they have Aubrey, they do not go on their mission. They instead hang out at their apartment, celebrate a birthday, go shopping, try to have sex a few times, and watch movies. After awhile, they decide it’s time to head up to Orbital-Land, where we quickly learn their intentions aren’t as pure as we thought. “Dad” and “Mom” are terrorists! And they’re planning on blowing up the entire Orbital community – while discussing sex of course.

I’m just going to tell you right now – Orbitals is getting the worst Scriptshadow rating there is. And I don’t want to discourage John because this is not a rating that reflects his writing for the rest of his life. It is a rating that reflects this script only. The great thing about screenwriting is that as long as you have the drive, you can keep learning, keep getting better. This is probably a rating that would reflect every screenwriter’s first screenplay – which I assume that this is – so try to take these notes as constructively as possible.

When I first got to LA, I wrote a script with a friend and we managed to finagle it into a few pretty big hands by basically lying our asses off. We told our few contacts that we’d written something that huge producers were interested in (lie), tricking them into reading it themselves.

Eventually, a really big agent agreed to “have lunch” with us and we prepared for our imminent big break. “I knew this was going to be easy,” I thought, mapping out which kind of car I was going to buy, a Bentley or a Ferrari. Now let me tell you something I learned in retrospect. This script was fucking AWFUL. Like the worst script you can imagine. It was about the internet coming alive or something. I don’t even remember exactly because I’ve tried to purge my brain of its existence. To give you an idea of how bad it was, we gave the script to a couple of 15 year olds since that was our target demo and one of them came back and said it was the single worst thing he had ever read in his life. He actually thought we were kidding. “You didn’t really write this, did you?” He was 15! 15 year olds like everything!

Anyway, we later realized (hindsight is a beautiful thing huh?) that the agent who was most certainly going to give us our big break, wanted nothing to do with us. She was doing a favor for the person who gave her the script, who she thought was a lot closer to us than she actually was. So she sent her crony assistant, this total Hollywood douchebag who spent more effort trying to pick up our waitress than talk to us, which in retrospect sucked because we convinced ourselves the guy was a moron and therefore ignored everything he said to us. But the guy gave us some really important advice that I only grasped 5-6 years later. This is what he said.

Writing screenplays is not a joke. You are competing against guys who have dedicated their lives to this craft, who have a 15-20 year head start on you. These are the Derek Jeters and the David Beckhams of the screenwriting world. They will spend 1-2 years on their screenplay. They will have written 30-40 drafts. They will go over every scene 200-300 times. They will make sure every line of dialogue is sharp, relevant, reveals character, and pushes the story forward. They will obsess over that screenplay like you wouldn’t believe. And because they’ve written 30 screenplays already, they will know where all the mistakes are and how to fix them.

If you think you can just slap together a high concept idea with 2 good scenes and a threadbare story that barely makes sense and compete with that? You’re off your fucking rocker.

The agent-assistant (whatever he was) then made us pick up the tab and went over and asked that waitress out (she said yes) and in that moment I hated everything about Hollywood. But you know what? He was right. He was so very right. This isn’t a joke. It doesn’t matter how many bad movies you’ve seen. If you expect to break in with a script you wrote in 14 days? If you think that professionals in this business won’t be able to tell that you wrote the script in 14 days, due to its unoriginality, its sloppiness, its 70% of scenes that repeat information we already know, its lack of character development? That readers won’t know that you didn’t think a single plot point through or do more than a single rewrite, you’re crazy. The guys who matter know these things. You cannot trick them.

That’s not to say newcomers can’t write something decent. But if you want a fighting chance, go out and read the 5 best-selling screenwriting books so you have SOME idea of how to tell a story. Read at least a hundred screenplays so you know what kind of quality you’re going up against. Plot out your story beforehand so it doesn’t look like something that was made up on the spot. When you’re finished, read through it and note all the places you were bored. Come up with solutions and then rewrite it. And when you’re finished, repeat that process. Again. And again. And again. Give it to friends and ask them what parts they liked and didn’t like. Incorporate those responses. Rewrite it again. And again. And again.

Honestly, I don’t know where to begin with Orbitals. I guess I’ll start with the basics. Movies are about only giving the audience the good parts and cutting out all of the boring stuff. Orbitals is written the opposite way. It only gives you the boring parts, and could care less about the interesting stuff.

For example, the script is supposedly about a couple who adopts a girl to get access to the orbiting system above earth that they normally wouldn’t have access to. Therefore, when they adopt the girl, you’d think that we’d be – you know – on our way to the orbiting system. No. Orbitals spends the next 50 pages back at the apartment with its two lead characters talking about sex. That is not the “good parts.” The equivalent would be like in Star Wars, after Obi-Wan and Luke went and got Han as their pilot to go to Alderran, they then went back to Obi-Wan’s hut, shot the shit for 50 minutes, and THEN went to Alderran. Honestly, we have one straight 50 minute chunk in Orbitals that could be axed and the screenplay would be exactly the same (actually it would be better because it would be over sooner). That’s not a good sign.

The reason this makes me so angry is because this is Screenplay 101 stuff here. This is some of the first stuff you learn when writing. And so the fact that it’s ignored tells me the writer hasn’t even attempted to learn the craft. I have less sympathy for Amateur Friday writers if they’re not taking the craft seriously. Once again, you’re stepping up to the plate facing a jacked up on steroids Roger Clemens in his prime. You better have spent as much time as possible learning the difference between fastballs and curveballs and sliders before you grace that batting box.

Another Screenplay 101 mistake is that every character in Orbitals talks EXACTLY THE SAME. This is probably the number 1 telltale sign that you’re dealing with a new writer. Everyone here uses “fuck” in equal disparity, meaning nobody sounds unique. All the conversations have the exact same rhythm. And worse, they are exactly the same scenes repeated over and over and over again. The parents want to have sex. We get it. We don’t need 13 scenes in a row telling us that, specifically since having sex has nothing to do with the plot.

And the scenes themselves are like 10-15 pages long. The average scene is supposed to be 2-3 pages long. A “long” scene is considered 5 pages. And you should only have a few of those in your script. 10-15 pages is a lifetime for a scene. There’s a moment in Orbitals where the characters sit down and watch The Shining for five pages, get in an argument, and then have another 5 minute scene talking about watching The Shining and getting in an argument! I don’t even know where to begin with that. Why are we wasting five pages of a screenplay with our characters watching a movie???

There’s no structure here. There’s no conflict. There are no stakes. There’s no urgency. The characters are all the same. The dialogue is repetitive. The story repeats itself. The script basically ignores every good storytelling tenet in the book. And again, this is more a condemnation on the writer for thinking it’s easy than it is on the writing itself. I feel that if John actually studied the craft, read a few books, learned the basics, mapped out a plot ahead of time instead of making it up as he goes along, he could come up with something a thousand times better than this. But this is all we have. And it’s a great reminder that this craft is a lot harder than everybody thinks it is.

Script link: Orbitals

[x] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Readers have strong negative – often angry – reactions to scripts like this because we’re pissed that the writer actually made us spend 2 hours of our lives reading something that they scraped together in a couple of weeks between Modern Warfare and World of Warcraft sessions. You’re going up against veteran screenwriters who know ALL the tricks in the book. Who know how to mine emotion on the page so that they already have the reader in the palm of their hand by page 5. You’re going up against people who are getting professional feedback from producers and agents, then going back and fixing their mistakes until there are no mistakes left. You’re going up against people who are not only pouring over every scene in their screenplay, but every *sentence.* Every *word*. You’re going up against writers who can attach Robert Pattinson or Leonardo DiCaprio to their screenplays. That’s your competition. That’s why you have to be perfect . Every writer loves that fever draft you shoot through in a couple of weeks. But believe it or not, that’s the easy part. The real work comes afterwards. In the rewriting. If you’re not willing to make that commitment, this business isn’t for you.

Aliens is, quite simply, awesome. It’s one of those movies that works if you’re 15 or you’re 35. It’s got action. It’s got mystery. It’s got emotion. And it’s in the running for best sequel ever. When I give notes, there’s no movie I reference more than this one. I’ve been known to bring up Aliens while consulting on a romantic comedy. That’s how rich it is in screenwriting advice. Now I could sit here and whine that “Studios just don’t make summer movies like this anymore.” But the truth is, they’ve never made these kinds of summer movies consistently – movies with depth, movies with thought, movies where the story takes precedence over the effects. But when they do, it’s probably the best moviegoing experience you can have. So, keeping that in mind, here are ten screenwriting lessons you can learn from one of the best summer movies of all time.

KILL YOUR BABIES

Listening in on the director’s commentary of Aliens, you find out that Aliens was originally 30 minutes longer, as it included an extra early sequence of the LV-426 colonists being attacked by the aliens. Under the gun to deliver a 2 hour and 10 minute film, Cameron reluctantly cut the sequence at the last second, and wow did it make a difference. Without it, there was more build-up to the aliens, more suspense, more anticipation. We were practically bursting with every peek around a corner, every blip of the radar. Now Cameron only figured this out AFTER he shot the unnecessary footage, but let this be a lesson to all of us screenwriters. Sometimes you gotta get rid of the things you love in order to make the story better. Always ask yourself, “Is this scene/sequence really necessary to tell the story?” You might be surprised by the answer.

NOT EVERY FILM NEEDS A LOVE STORY

There’s a temptation to insert a love story into every movie you write, especially big popcorn movies, since the studios are trying to draw from every “quadrant” possible and therefore need a female love interest to bring in the female demographic. But there are certain stories where no matter what you do, it won’t fit. And if you’ve written one of those stories, don’t try to force it, because we’ll be able to tell. I thought Cameron handled this issue perfectly in Aliens. He knew a love story in this setting wasn’t going to fly, so instead he created “love story light,” between Ripley and Hicks, where we see them flirting, where we can tell that in another situation, they might have worked. But it never goes any further than that because tonally, and story-wise, he knew we wouldn’t have accepted it.

ALWAYS MAKE THINGS WORSE FOR YOUR CHARACTERS

As I’ve stated here many times before, one of the most potent tools a screenwriter possesses is the ability to make things worse for their characters. In action movies, that usually means escalating danger whenever possible. Aliens has one of the most memorable examples of this, when our characters are moving towards the central hub of the station, looking for the colonists, and Ripley realizes that, because they’re sitting on a nuclear reactor, they can’t fire their guns. The Captain informs his Lieutenant that he needs to collect all of the soldiers’ ammo (followed by one of the greatest movie lines ever “What are we supposed to use? Harsh language?”), and now, with our marines moving towards the nest of one of the most dangerous species in the universe, they must take them on WITHOUT FIREPOWER. Always make things worse for your characters!

USE YOUR MID-POINT TO CHANGE THE GAME

Something needs to happen at your midpoint that shifts the dynamic of the story, preferably making things worse for your characters. If you don’t do this, you run the risk of your second half feeling a lot like your first half, and that’s going to lead to boredom for the reader. In Aliens, their objective, once they realize what they’re up against, is to get up to the main ship and nuke the base. The mid-point, then, is when their pick-up ship crashes, leaving them stranded on the planet. Note how this forces them to reevaluate their plan, creating a second half that’s structurally different from the first one (the first half is about going in and kicking ass, the second half is about getting out and staying alive).

GET YOUR HERO OUT THERE DOING SHIT – KEEP THEM ACTIVE

Cameron had a tough task ahead of him when he wrote this script. Ripley, his hero, is on the bottom of the ranking totem pole. How, then, do you believably prop her up to become the de facto Captain of the mission? The answer lies inside one of the most important rules in screenwriting: You need to look for any opportunity to keep your hero active. Remember, THIS IS YOUR HERO. They need to be driving the story whenever possible. Cameron does this in subtle ways at first. While watching the marines secure the base, Ripley grabs a headset and makes them check out an acid hole. She then voices her frustration when she doesn’t believe the base to be secured. Then, of course, comes the key moment, when the Captain has a meltdown and she takes control of the tank-car and saves the soldiers herself. The important thing to remember is: Always look for ways to keep your hero active. If they’re in the backseat for too long, we’ll forget about them.

MOVE YOUR STORY ALONG

Beginning writers make this mistake constantly. They add numerous scenes between key plot points that don’t move the story forward. Bad move. You have to move from plot point to plot point quickly. Take a look at the first act here. We get the early boardroom scene where Ripley is informed that colonists have moved onto LV-426. In the very next scene, Burke and the Captain come to Ripley’s quarters to inform her that they’ve lost contact with LV-426. You don’t need 3 scenes of fluff between those two scenes. Just keep the story moving. Get your character(s) to where they need to be (in this case – to LV-426).

THE MORE UNLIKELY THE ACTION, THE MORE CONVINCING THE MOTIVATION MUST BE

You always have to have a reason – a motivation – for your character’s actions. If a character is super happy and loves life, it’s not going to make sense to an audience if they step in front of a bus and kill themselves. You need to motivate their actions. In addition to this, the more unlikely the action, the more convincing the motivation needs to be. So here, Burke wants Ripley to come with them to LV-426 as an advisor. Answer me this. Why the hell would Ripley put herself in jeopardy AGAIN after everything that just happened to her – what with the death of her entire crew, her almost biting it, and barely escaping a concentrated acid filled monster? The motivation here has to be pretty strong. Well, because the military holds Ripley responsible for their destroyed ship, she’s basically been relegated to peasant status for the rest of her life. Burke promises to get her job back as officer if she comes and helps them. That’s a motivation we can buy.

STRONG FATAL FLAW – RARE FOR A SUMMER MOVIE

What I loved about Aliens was that Cameron gave Ripley a fatal flaw. Usually, you don’t see this in a big summer action movie. Producers see it as too much effort for not enough payoff. But giving the main character of your action film an arc – and I’m not talking a cheap arc like alcoholism – is exactly what’s made movies like Aliens stand the test of time while all those other summer movies have faded away. So what is Ripley’s flaw? Trust. Or lack of it. Ripley doesn’t trust Burke. She doesn’t trust this mission. She doesn’t trust the marines. And she especially doesn’t trust Bishop, which is where the key sequences in this character arc play out. In the end, Ripley overcomes her flaw by trusting Bishop to come back and get them. This is why the moment when she and Newt make it to the top of the base is so powerful. For a moment, she was right. Bishop left them there. She never should’ve trusted him. Of course the ship appears at the last second and her arc is complete. She was, indeed, right to leave her trust in someone.

SEQUENCE DOMINATED MOVIE

One way to keep your movie moving is to break it down into sequences. Each sequence should act as a mini-movie. That means there should be a goal for each specific sequence. In the end, the characters either achieve their goal or fail at it, and we then move on to the next sequence. Let’s look at how Aliens does this. Once they’re on LV-426, the goal is to go in and figure out what the fuck is going on (new sequence). Once they find the colony empty, their goal shifts to finding out where the colonists are (new sequence). After that ends with them getting attacked by aliens, their goal becomes get off this rock and nuke the colony (new sequence). Once that fails, their goal becomes secure all passageways so the aliens can’t get to them (new sequence). Once that’s taken care of, the goal is to find a way back up to the ship (new sequence). Because there’s always a goal in place, the story is always moving. Our characters are always DOING SOMETHING (staying ACTIVE). The sequence approach is by no means a requirement, but I’ve found it to be pretty invaluable for action movies.

ACTIONS SPEAK LOUDER THAN WORDS (SHOW DON’T TELL!)

Aliens has one of the best climax fights in the history of cinema (“Get away from her you BITCH.”) And the reason it works so well? Because it was set up earlier, when Ripley shows the marines she’s capable of operating a loader (“Where do you want it?” she asks). Ahh, but I have a little surprise for you. Go pop Aliens in and fast-forward it to the early scene where Burke first comes to recruit Ripley. THIS is actually the first moment where the final fight is set up. “I heard you’re working the cargo docks,” Burke offers, smugly. “Running forklifts and loaders and that sort of thing?” It’s a quick line and I bring it up for an important reason. I bet none of you caught that line. Even if you’ve watched the film five or six times. That line probably slipped right by you. And the significance of it slipping by you is the point of this tip. You should always SHOW instead of TELL. When we SEE Ripley on that loader, it resonates. When we hear it in a line, it “slips right by us.” Had we never physically seen Riply on that loader, and Cameron had depended instead on Burke’s quick line of dialogue? There’s no way that final battle plays as well as it does. Always show. Never tell.

AND THERE YOU HAVE IT

I actually had 15 more tips, but contrary to popular belief, I do have a life, so those will have to wait for another day. I do have a question for all Aliens nerds out there though. How do they pull off the Loader special effects? I know in some cases it’s stop motion. And in other cases, Cameron says there’s a really strong person behind the loader, moving it. But there are certain shots when you can see the loader from the side that aren’t stop motion and nobody’s behind it. So how the hell does it still look so real? I mean, these are 1986 special effects we’re talking about here! Tune in next week where I give you 10 tips on what NOT to do via the disaster that was Alien 3.

These are 10 tips from the movie “Aliens.” To get 490 more tips from movies as varied as “Star Wars,” “When Harry Met Sally,” and “The Hangover,” check out my book, Scriptshadow Secrets, on Amazon!

The word “rules” stirs up a lot of debate in the University of Screenwriting. Some believe there should be no rules when you write. Others believe rules are the lifeblood of a screenplay. I fall somewhere in between. You definitely need to know the rules. Whether you choose to use them, however, is up to you. The thing is, most great scripts break at least a couple of rules. Why? Because if you follow ALL the rules then your story will be predictable, average, and boring. You need to take those chances in order to stand out. The problem is when these deviations get celebrated and writers erroneously believe that that’s proof rules aren’t important (“Quentin Tarantino writes 10 page dialogue scenes, so why can’t I!”). Rules are extremely important. David Mamet uses them

. Aaron Sorkin uses them. Michael Arndt (Toy Story 3

) lives by them. The key is knowing what rules you’re breaking so you can adapt your screenplay to absorb the breakage. Here are 7 memorable movies, the major screenwriting rules they break, and why they still worked.

The Social Network

Rule Broken: Page Count 162 pages

Why It Didn’t Matter: 162 pages! I get mad at people who write 122 pages. Who in the world gets to write 40 more pages than THAT and still get a pass? Why Aaron Sorkin of course! The man who could write a script in comic sans on discarded wallpaper and still get away with it. Well, before you think about reinstating that 30 page subplot about your hero’s blind Nazi mistress who’s just come down with a bout of scurvy, let’s take a look at the content of this behemoth. Go ahead and open up The Social Network right now. What I’m betting you’ll find is dialogue. Lots of dialogue. I’d go as far as to say that The Social Network is 95% dialogue. That’s important for two reasons. One, dialogue reads a LOT faster than action, making a 162 page script fly by like it’s 110 pages (Fincher actually shot the draft word for word and it ended up being under 2 hours). And two, dialogue is this particular writer’s biggest strength. If the reason your script is too long is because you have a lot of dialogue and you’re a dialogue master, then it’s not going to read like a script that’s too long. Now does this mean you get to write a 160 page script if it’s all dialogue? Hell no. Learn to be great with dialogue, put a few hit shows on the air famous for their dialogue, get a dialogue driven-script near the top of the Black List, THEN maybe you can write that 160 pager. But I’d still stick with the good old 110 page rule. That’ll force you to learn one of the most important skills in screenwriting, cutting out the pieces of the story that don’t matter.

Titanic

Rule Broken: The inciting incident doesn’t happen until 2 hours into the story.

Why It Didn’t Matter: The inciting incident is the incident that throws your hero into peril, that forces him or her to go on their journey. It usually happens around 15 minutes into the story (In Shrek, it’s when his swamp is invaded). Some might say that the inciting incident in Titanic is Jack meeting Rose. Some might say it’s Rose meeting Jack. And you can probably make a good case for either of those. But to me, what really incites this story is when the ship hits the iceberg. And that doesn’t happen until a full 2 hours into the movie. That means we’re stuck watching two people diddle around a ship and fall in love for two hours! Doesn’t that sound boring to you? And yet it works. You want to know why? Because Titanic has one of the most unique and powerful story advantages in the history of cinema – a built in super-dose of dramatic irony. Dramatic irony is when we the audience know something about the characters and their situation before they do, preferably something that puts them in danger. Remember in Die Hard when McClane gets stuck up on the roof with Hanz, who pretends to be a hostage but WE KNOW he’s the villain? That scene is exciting because of the dramatic irony. *We* know McClane is in trouble. But he doesn’t. Well Titanic has the mother of all dramatic ironies. We know that the Titanic is going to sink, and our poor characters don’t. So we watch for 2 hours with baited breath, wondering how they’re going to handle it, what they’re going to do when it happens, and specifically what will happen to Jack, since he’s unrepresented in the modern day storyline. Cameron could’ve added a whole extra hour in front of the iceberg collision if he wanted to because he had the single biggest case of dramatic irony on his side during the story. I don’t know if there can ever be another movie with this advantage. But I do know that a solid dose of dramatic irony will allow you to push key story points back if need be.

Lost In Translation

Rule Broken: No character goal

Why It Didn’t Matter: Lost In Translation is a story that wanders. Which makes sense because it’s about a girl stuck in a city where she doesn’t understand the language or know anyone. So the fact that she doesn’t have a goal stems organically from the situation. But make no mistake, if you’d had Scarlett Johanson, voluptuous as she is, wandering around Tokyo and riding trains for 2 straight hours, we would’ve killed ourselves by minute 40. If you don’t have a goal, you need to create a dramatic question that will drive the story. That question almost always comes in the form of a romantic interest. Bring in another character and now your dramatic question is posed: “Will these two end up together?” Or “What will happen between these two?” But Coppola takes it a step further. Had the person our protagonist met been some suave-ish good-looking 20-something who’s also stuck in Tokyo for a few weeks, that would’ve been a boring question. Because we’d already know the answer (“Yes, of course they’ll end up together”). Instead, she introduces an offbeat, older, weird guy who’s about as opposite from her as they come. Now that question has some real meat to it, some real uncertainty. I still recommend giving your characters a goal AND adding a dramatic question (in the recently discussed spec, “Seeking A Friend At the End Of The World,” about two people who meet a few days before the earth is to be struck by an asteroid, the couple is trying to reach a certain location (goal) and we’re wondering if they’re going to end up together (question)). But if you can’t add that goal, like Lost In Translation, you better add an interesting question to the mix or else there’s no reason for us to watch.

Apollo 13

Rule Broken: Audience already knows how the story ends.

Why It Didn’t Matter: I don’t’ know if I’d call this a broken rule per se, but it is something that a lot of famous real-life stories have to deal with, and Apollo 13 was one of the more famous ones so it’s worth exploring. How do you make a disaster movie work when everybody who sees it knows that your main characters get out alive? If dramatic irony is the audience being ahead of the characters in knowing something bad is going to happen to them, isn’t this the opposite? Which would then create the opposite effect? “Oh, well we know they’re going to be okay, so who cares?” Writers Broyles Jr. and Reinert, under Ron Howard’s direction, did two things to combat this problem. First, they made sure you loved these characters more than anything. That was key. Once we love the characters, we’re going to care about any threatening situation they’re in. And second, they always kept the focus on THE HERE AND NOW. Apollo 13 hits its characters with one obstacle after another, each one bigger and with larger implications than the last, sometimes compounding these obstacles on top of each other (they need to get the navigation data while coming up with a way to conserve air). Their journey is so battered with obstacles that all we’re focusing on is the RIGHT NOW. They’re so focused on surviving that so are we. If they didn’t have all these things to do up there. Had the obstacles been less challenging or not as many, there’s a good chance we would’ve seen through the charade and said, “Hey, don’t these guys all live? Who gives a shit?”

Rush Hour

Rule Broken: Derivative story execution

Why It Didn’t Matter: Being derivative is one of those mistakes that 99.999% of scripts can’t overcome. If we’ve seen it before, we will not want to see it again. Yet Rush Hour has one of the most derivative stories you can imagine and still works. This script is 48 Hours. This script is Lethal Weapon

. This script is Beverly Hills Cop

. It doesn’t even try to be anything else. So then why does it still work? Because the central relationship/dynamic is unique. We’ve never quite seen the pairing of an African American and a Chinese cop before. And so while everything that’s going on around them is shit we’ve seen a thousand times before, we excuse it because we’ve never seen this particular dynamic before. Now the screenwriting purist in me will beg you to write an original story AS WELL as have an original central relationship. However, if your buddy cop film (or romantic comedy, or road trip comedy) has a ho-hum storyline, make sure your central relationship is new/interesting/fresh/exciting in some way. You just might be able to cover-up the fact that your story is been-there-done-that.

Big

Rule Broken: No urgency (no ticking time bomb)

Why It Didn’t Matter: On its surface, Big is one of those scripts that seems like it follows the Hollywood formula to a tee. Well, yeah, concept-wise, it does. But the next time Big is on, fire up some popcorn and pay attention to the plot. What you’ll see is that there’s no urgency to the story at all. There *is* a time frame (I believe it’s six weeks until the wish-machine shows up again) but Hanks isn’t in a hurry to accomplish anything in the story. Contrast this with another high-concept comedy, Liar Liar, where Jim Carrey must figure out how to lie again before the big trial that night. So why does Big still work even though Tom Hanks’ character isn’t in a hurry to achieve anything? Because Big exploits its high concept premise better than almost every high concept comedy in history. From him playing on the giant piano with the boss to becoming a top toy company executive to being with a woman for the first time. Big gives you everything you want to see when you think of a kid getting stuck in a man’s body, and that helps us forget the fact that Hanks doesn’t have anything to actually do in this world.

Star Wars

Rule Broken: Main character isn’t introduced until 15 minutes into the story.

Why It Didn’t Matter: These days, if you’re not introducing your main character in the very first scene, then you sure as hell better be introducing him in the second one. Anything beyond that, and it’s no soup for you. The hero is the person the audience identifies with. We want to meet him as soon as possible. So then how does one of the greatest movies in history introduce its main character fifteen minutes into the story and get away with it? The answer is simpler than you think. It doesn’t matter that it takes so long for our hero to arrive because AN EXCITING STORY IS HAPPENING IN THE MEANTIME. Characters with immediate wants are tracking down characters with harmful plans. People are being killed to retrieve information. There’s mystery. Excitement. High stakes. Why would we be thinking about our main character when so much story awesomeness is going on? Had we started with Darth Vader chilling out on his throne back on Coruscant casually inquiring if his cronies had located the Death Star plans yet… Had we cut to R2 and C3PO casually landing on Tantooine, in no rush to find Obi-Wan… then yeah, we probably would’ve been like, dude, where the fuck is the main character?? But the intensity of the story, the immediacy of everyone’s actions, the mystery behind why it was all happening, kept us engaged to the point where we just weren’t thinking about it.

And there you go. Seven movies. Seven broken rules. Seven reasons why those movies still worked. Remember, no rule is carved in stone. Any rule can be broken. But if you’re going to break it, know why you’re breaking it and make sure it’s for a good reason. Otherwise, you’re flying by the seat of your pants. I’m still waiting for the first great script that isn’t built on a foundation of solid storytelling. I don’t think that script is coming any time soon so best to stick with what’s worked for thousands of years.

Genre: Horror

Premise: A group of paranormal researchers move in to the most haunted mansion in the world to try and prove the existence of ghosts.

About: One of our longtime commenters has thrown his hat into the ring. Very excited to finally be reviewing Andrew Mullen’s script! — Every Friday, I review a script from the readers of the site. If you’re interested in submitting your script for an Amateur Review, send it in PDF form, along with your title, genre, logline, and why I should read your script to Carsonreeves3@gmail.com. Keep in mind your script will be posted.

Writer: Andrew Mullen

Details: 146 pages (This is an early draft of the script. The situations, characters, and plot may change significantly by the time the film is released. This is not a definitive statement about the project, but rather an analysis of this unique draft as it pertains to the craft of screenwriting).

Andrew’s been commenting on Scriptshadow forever and I like to reward people who actively participate on the site, so I was more than happy to choose his script for this week’s Amateur Friday. Seeing that Andrew had always made astute points and solid observations, I was hoping for a three-for-three “worth the read” trifecta over the last three Amateur Fridays. What once seemed impossible was shaping up to be possible.

And then I saw the page count.

Pop quiz. What’s the first thing a reader looks at when he opens a screenplay? The title? No. The writer’s name? No. That little box on the top left corner of the PDF document that tells you how many pages it is? Ding ding ding! I saw “146” and my eyes closed. In an instant, all of the energy I had to read Shadows was drained. I know Andrew reads the site so I know he’s heard me say it a hundred times: Keep your script under 110 pages. Of all the rules you want to follow, this is somewhere near the top. And it has nothing to do with whether it’s possible to tell a good story over 110 pages. It has to do with the fact that 99.9% of producers, agents, and managers will close your script within 3 seconds of opening it after seeing that number. They will assume, rightly in 99.9% of the cases, that you don’t know what you’re doing yet, and move on to the next script.

Which is exactly what I planned to do. I mean, I have a few hundred amateur scripts that don’t break the 100 page barrier. I would be saving 45 minutes of my night to do something fun and enjoyable if I went back to the slush pile. But then I stopped. I thought, a) I like Andrew. b) This could serve as an example to amateur writers WHY it’s a terrible idea to write a 146 page script. And c) Maybe, just maybe, this will be that .01% of 146 page screenplays that’s good and force me to reevaluate how I approach the large page count rule.

So, was Shadows in that .01%?

Professor Malcom Dobbs and Dr. Butch Rubenstein are founders of the premiere paranormal research team on the planet. They’re the “Jodie Foster in Contact’s” of the paranormal world, willing to go to the ends of the earth to prove that ghosts do, in fact, exist. And they’re currently residing in the best possible place to prove this – a huge mansion with sprawling grounds known as Carrion Manor – a house many consider to be the most haunted in the world.

But with their grant running out, so is their time to prove the existence of ghosts, so the group is forced to take drastic measures. They head to a local nut house and ask for the services of 20-something Brenna, a pretty and kind woman with a dark past. Her entire family was slaughtered when she was a child, and that night she claimed to have heard voices, whispers, contact from another realm. This “contact” is exactly what our team needs to ramp up their experiments.

Basically, what these guys do is similar to the “night vision” sequence in the great horror film, “The Orphanage,” where they use all their technical equipment like computers, and cameras, and microphones, to monitor levels of energy as Brenna walks from room to room throughout the manor. This is one of the first problems I had with the script. There isn’t a lot of variety to these scenes. And we get a lot of them. Brenna walks into a room. The levels spike. Our paranormal team is excited. Some downtime. Then we repeat the process again.

During Brenna’s stay, she starts to fall for one of the team members, a child genius (now 27 years old) named Dr. Schordinger Pike. This was another issue I had with the script, as the development of Pike and Brenna’s relationship was way too simplistic, almost like two 6th graders falling in love, as opposed to a pair of 27 year olds (“She’s way out of my league. Right? Right. Not even the same sport!” Pike starts hyperventilating). Also, I find that when the love story isn’t the centerpiece of the film (in this case, the movie is about a haunted mansion) you can’t give it too much time. You can’t stop your screenplay to show the two lovers running through daisies and professing their love for one another. You almost have to build their relationship up in the background. Empire Strikes Back is a great example of this. Han and Leia fall in love amongst a zillion other things going on. Whereas here, we stop the story time and time again to give these two a scene where they can sit around and talk to each other. Always move your story along first. Never stop it for anything.

Anyway, another subplot that develops is the computer system that’s monitoring the house, dubbed “Casper.” Casper is the “Hal” of the family, and when things start going bad (real ghosts start appearing), Casper wants to do things his way. You probably know what I’m going to say here. A computer that controls the house is a different movie. It has nothing to do with what these guys are doing and therefore only serves to distract from the story. You want to get rid of this and focus specifically on the researchers’ goal (trying to prove that there are ghosts) and the obstacles they run into which make achieving that goal difficult.

I will say there’s some pretty cool stuff about the eclectic group of former house owners, and the fact that a lot of them had unfinished business when they died clues us in that we’ll be seeing them again. And we do. The final act is 30 intense pages of paranormal battles with numerous ghosts and creatures coming to take down our inhabitants, some of whom fall victim to the madness, some of whom escape. But there are too many dead spots in the script, which makes getting to that climax a chore.

So, the first thing that needs to be addressed is, “Why is this script so long?” I mean, did we really need this many pages to tell the story? The simple and final answer is no. We don’t need nearly this many pages. The reason a lot of scripts are too long is usually because a writer doesn’t know the specific story they’re trying to tell, so they tell several stories instead. And more stories equals more pages. This would fall in line with my previous observation, that we have the needless “Casper” subplot and a love story that requires the main story to stop every time it’s featured.

Figure out what your story is about and then ONLY GIVE US THE SCENES THAT PUSH THAT PARTICULAR STORY FORWARD. Doesn’t mean you can’t have subplots. Doesn’t mean you can’t have a minor tangent or two. But 98% of your script should be working to push that main throughline forward. So if you look at a similar film – The Orphanage – That’s a film about a woman who loses her son and tries to find him. Go rent that movie now. You’ll see that every single scene serves to push that story forward (find my son). We don’t deviate from that plan.

Another problem here is the long passages where nothing dramatic happens. There’s a tour of the house that begins on page 59 that just stops the story cold. We start with a couple of flirty scenes between Brenna and Pike as we explore a few of the rooms. Then we go into multiple flashbacks of the previous tenants in great detail, one after another. After this, Pike offers us a flashback of his OWN history. So we had this big long exposition scene regarding the house. And we’re following that with another exposition scene. Then Pike shows Brenna the house garden, another key area of the house, and more exposition. This is followed by another character talking about a Vietcong story whose purpose remains unclear to me. The problem here, besides the dozen straight pages of exposition, is that there’s nothing dramatic happening. No mystery, no problem, no twist, nothing at stake, nothing pushing the story forward. It’s just people talking for 12 minutes. And that’s the kind of stuff that will kill a script.

Likewise, there are other elements in Shadows that aren’t needed. For example, there’s a character named Lewis, a slacker intern who never does any work, who disappears for 50-60 pages at a time before popping back up again. We never know who the guy is or why he’s in the story. Later it’s discovered he’s using remote portions of the house to grow pot in. I’m all for adding humor to your story, but the humor should stem from the situation. This is something you’d put in Harold and Kumar Go To Siberia, not a haunted house movie. Again, this is the kind of stuff that adds pages to your screenplay and for no reason. Know what your story is and stay focused on that story. Don’t go exploring every little whim that pops into your head – like pot-growing interns.

This leads us to the ultimate question: What *is* the story in Shadows? Well, it’s almost clear. But it needs to be more clear. Because the clearer it is to you, the easier it will be to tell your story. These guys are looking for proof of the paranormal. I get that. But why? What do they gain by achieving this goal? A vague satisfaction for proving there are ghosts? Audiences tend to want something more concrete. So in The Orphanage, the goal is to find the son (concrete). In the recently reviewed Red Lights, a similar story about the paranormal, the goal is to bring down Silver (concrete). If there was something more specific lost in this house. Or something specific that happened in this house, then you’d have that concrete goal. Maybe they’re trying to prove a murder or find a clue to some buried treasure on the property? Giving your characters something specific to do is going to give the story a lot more juice.

Here’s the thing. There’s a story in here. Paranormal guys researching ghosts in the most haunted house in the world? I can get on board with that. And there’s actually some pretty cool ideas here. Like the old knight who used to live on the property who was never found. There’s potential there. But this whole story needs to be streamlined. I mean you need to book this guy on The Biggest Loser until he’s down to a slim and healthy 110 pages. Because people aren’t going to give you an opportunity until you show them that you respect their time. I realize this is some tough love critiquing going on here, but that’s only because I want Andrew to kick ass on the rewrite and on all his future scripts. And he will if he avoids these mistakes. Good luck Andrew. Hope these observations helped. :)

Script link: Shadows

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: This script was a little too prose-heavy, another factor contributing to the high page count. You definitely want to paint a picture when you write but not at the expense of keeping the eyes moving. Lines like this, “A dying jack o’ lantern smiles lewdly. The faintly glowing grimace flickers in the dark as if struggling for life,” can easily become “A flickering jack o’ lantern smiles lewdly,” which conveys the exact same image in half the words. Just keep it moving.

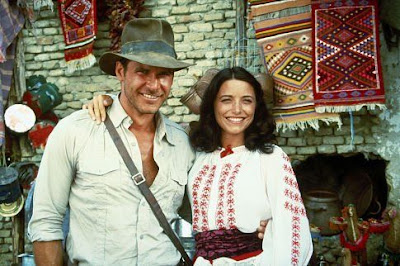

A couple of weeks back I posted my “10 Great Things About Die Hard” article and you guys responded. To quote Sally Fields: “You loved it! You really loved it!” Since I had so much fun breaking the movie down, you can expect this to be a semi-regular feature, and today I’m following it up with a film I’ve always wanted to dissect: Raiders Of The Lost Ark.

When it comes to summer action movies, there aren’t too many films that hold a candle to the perfectly crafted Raiders. Many have tried, and while some have cleaned up at the box office (Mummy, Tomb Raider

) they haven’t remained memorable past the summer they were released.

So what makes Indiana Jones such a classic? What makes this character one of the top ten movie characters of all time? Here are ten screenwriting choices that made Raiders Of The Lost Ark so amazing.

THE POWER OF THE ACTIVE PROTAGONIST

At some point in the evolution of screenwriting, a buzz word was born. The “active” protagonist. This refers to the hero who makes his own way, who drives the story forward instead of letting the story drive him. I don’t know when this buzz word became popular exactly, but I’m willing to bet it was soonafter Raiders debuted. One of the things that makes Indiana Jones such a great character is how ACTIVE he is. In the very first scene, it’s him who’s going after that gold idol. It’s him driving the pursuit of the Ark Of The Covenant. It’s him who decides to seek out Marion. It’s him who digs in the alternate location in Cairo. Indiana Jones’ CHOICES are what push this story forward. There’s very little “reactive” decision-making going on. And the man is never once passive. The “active” protagonist is the key ingredient for a great hero and a great action movie.

THE ROADMAP TO A LIKABLE HERO

Indiana Jones is almost the perfect character. Believe it or not, however, it isn’t Harrison Ford’s smile that makes Indy work. The screenplay does an excellent job of making us fall in love with him, and does so in three ways. 1) Indiana Jones is extremely active (as mentioned above). We instinctively like people who take action in life. They’re leaders. And we like to follow leaders. 2) He’s great at what he does. When we see Indiana cautiously avoid the light in the cave, casually wipe away spiders, or use his whip to swing across pits, we love him, because we’re drawn to people who are good at what they do. And 3) He’s screwed over. This is really the key one, because it creates sympathy for the main character. We watch as our hero risks life and limb to get the gold idol, only to watch as the bad guy heartlessly takes it away. If you want to create sympathy for a character, have them risk their life to get something only to have someone take it from them afterwards. We will love that character. We will want to see him succeed. I guarantee it.

ACTION SEQUENCES

When you think back to Indiana Jones, what you remember most are the great action sequences. Nearly every one of them is top notch. And there’s a reason for that. CLARITY . Each action sequence starts with a clear objective. Indiana tries to get the gold idol in the cave. Indiana must save Marion in the bar. Indiana must find the kidnapped Marion in the streets of Cairo. Indiana must destroy the plane that’s delivering the Ark. It’s so rare that we see action sequences these days with a clear objective, which is why so many of them suck. Look at Iron Man 2 for example. What the hell was that car race scene about? We have no idea, which is why despite some cool lightning whip special effects from Mickey Rourke, the scene sucked. Always create a clear objective in your action scenes.

REMIND YOUR AUDIENCE HOW DIFFICULT THE GOAL IS

High stakes are primarily created by crafting a hero who desperately wants to achieve his goal. I don’t know anyone who wants anything as much as Indiana Jones wants that Ark. But in order to build those stakes even higher, you want to remind the audience just how important and difficult it will be for your hero to achieve that goal. For example, there’s a nice little quiet scene in Raiders right before Indiana goes on his journey where his boss reminds him what finding the Ark means. “Nobody’s found the Ark in 3000 years. It’s like nothing you’ve gone after before.” It’s a small moment, but it’s a great reminder to the audience. “Whoa, this is a really big freaking deal.”

IGNORE THE RULES IF IT SUITS YOUR STORY

Part of becoming a great screenwriter is learning when rules don’t apply to the specific story you’re telling. Each story is unique and therefore forces you to make unique choices. One of the commonly held beliefs with any hero journey is that there must be a “refusal of the call.” When Luke is given the chance to help Obi-Wan, he backs down, “I can’t do that,” he says. “I still have to work on the farm.” Indiana Jones, however, never refuses the call. And Raiders is a better movie for it. Because the thing we like so much about Indiana Jones is that he’s gung-ho, that he’s not afraid of anything. So if the writers had manufactured a “refusal of the call” moment, with Indy saying, “But I have to stay here and teach. I have a dedication to the university,” it would’ve felt stale and forced. So whenever you’re trying to incorporate a rule into your story that isn’t working, consider the possibility that you may not need it.

GIVE A GREAT INTRO TO YOUR FEMALE LEAD

I can’t tell you how many male writers make this mistake (and how many female writers make this mistake in reverse). You need to put just as much thought into your female lead’s introductory scene as you do your male’s. Raiders is a perfect example of this. Indiana Jones has one of, if not the, greatest introductory scene in a movie ever. If you don’t give that same dedication and passion to Marion’s introduction, she’s going to disappear. That’s why, even though her entrance doesn’t compare to Indiana’s, it’s still pretty damn good. We have the great drinking competition scene followed by the battle with German/Nepalese thugs. The girl is badass, swallowing rum from a bullet hole leak in the middle of a life or death battle! Always always always give just as much thought to your female introduction as your male’s.

ADD IMMEDIACY AT EVERY TURN

The pace of Indiana Jones still holds up today, 25 years later. Not an easy task when you’re battling with the likes of Michael Bay and Steven Sommers, directors who have ruined audience’s attention spans with their ADD like cutting. Raiders achieves this pace not through dizzying editing tricks, but through good old fashioned story mechanics, specifically its desire to add immediacy to the story whenever the opportunity arises. Take when Indy arrives in Cairo for example. The first thing he’s told when he gets there is that the Germans are close to finding the Well of Souls! What?? This was supposed to be a simple one-man expedition! Now he’s in direct competition with a team of hundreds of men??? Because of this added immediacy, the stakes are raised and Indiana’s pursuit of his goal is more entertaining. So always look to add immediacy to your action movie where you can!

IF YOU HAVE A BORING CONVERSATION, INJECT SOME SUSPENSE INTO IT

You are always going to have two person dialogue scenes in your movie. These scenes can get very boring very quickly, especially in an action film. There’s a scene after Indy and Marion get to Cairo where they walk around the city. Technically, we don’t need this scene but it does help establish the relationship between the two, which is important for later on. Now a lesser writer may have sat these two in a room and had them divulge their pasts to each other in a boring explosion of exposition. Instead, Kasdan has them walking around, and *cutting to various bad guys getting in position to attack them.* This adds an element of suspense to the conversation, since we know that sooner or later, something bad is going to happen to our couple. MUCH more interesting than a straight forward dialogue scene between your two leads.

MOVING ON FROM DEATH IN AN ACTION MOVIE

Many times you’ll run into an issue where a major character in your movie dies. Yet you somehow must make us believe that your hero is willing to continue his journey. The perceived death of Marion creates this problem in Raiders. The formula to solve the problem? A quick 1-2 page scene of mourning, followed by the hero being placed in a dangerous situation. The mourning shows they properly care about the death, then the danger tricks the audience into forgetting about said death, allowing you to jump back into the story. So in Raiders, after Marion “dies,” Indiana sits back in his room, depressed, then gets a call from Belloq. The dangerous Belloq questions what Indie knows, followed by the entire bar prepping to shoot him. After that scene you’ll notice you’ve sort of forgotten about Marion, as crazy as it sounds. This exact same formula is used in Star Wars. Obi-Wan dies, we get the quick mourning scene on the Falcon, and then BOOM, tie fighters attack them, seguing us back into the thick of the story.

INDIANA’S ONE FAILURE – CHARACTER DEVELOPMENT

Raiders is about as perfect a movie as they come. However, it does drop the ball on one front. Indiana Jones is not a deep character. Now because this is an action movie, it doesn’t really matter. However, I’d argue that the script did hint at a character flaw in Indiana, but ultimately chickened out. Specifically, there’s a brief scene inside the tent when Indiana discovers Marion is still alive. This presents a clear choice: Take Marion and get the hell out of here, or keep her tied up so he can continue his pursuit of the Ark. What does he do? He continues his pursuit of the Ark. This proves that Indiana does have a flaw. His pursuit of material objects (his work) is more important to him than his relationships with real people (love). However, since this is the only true scene that presents this flaw as a choice, it’s the only time we really get inside Indiana’s head. Had we seen a few more instances of him battling this decision, I think Raiders would’ve hit us on an even deeper level.

Tune in next week when I dissect Indiana Jones and The Kingdom Of The Crystal Skull!