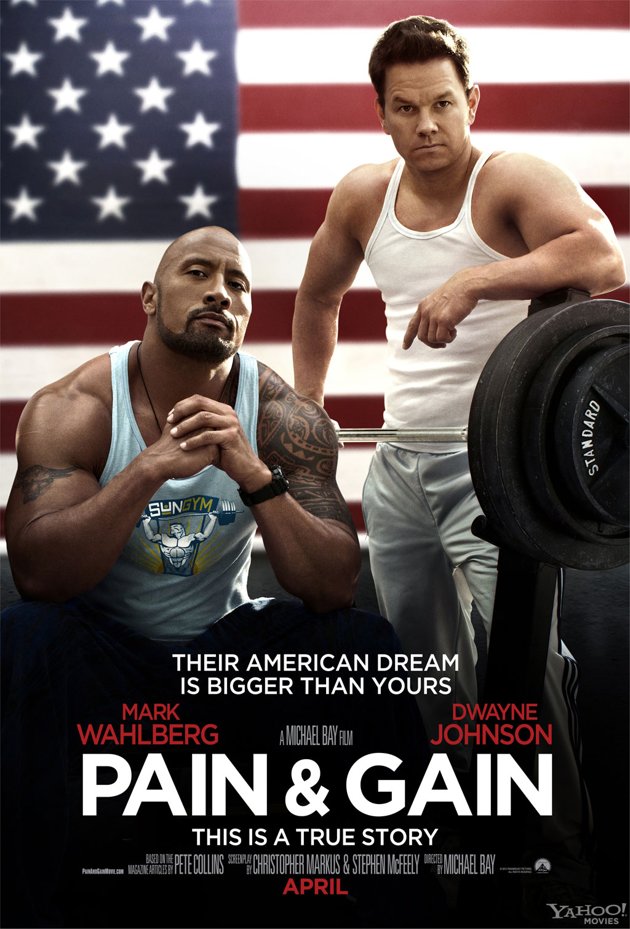

Michael Bay goes indie on us. Does he finally realize what a screenplay is in the process?

Genre: Action/Comedy/Crime

Premise: Based on a true story, a fitness trainer kidnaps one of his rich clients, eventually taking over his life. He must then fend off the man’s attempts to claim his life back.

About: This is Michael Bay’s version of an indie film – something he’s talked about doing for over a decade. It stars Mark Wahlberg and The Rock and comes out April 26th. Bay and Wahlberg got along so well during filming, Bay convinced Marky Mark (the busiest actor in Hollywood) to be in the next Transformers movie. P&G is written by big-budget scribes Christopher Markus and Stephen McFeely, who scripted the three Narnia screenplays, the first Captain America script, and are doing the next Thor and Captain America scripts respectively. However, because it’s Bay’s baby, and he was shepherding pretty much the whole writing process, I’ll be looking at this, basically, as his script.

Writers: Christopher Markus & Stephen McFeely (revisions by Jerry Stahl) (Current Revisions by Christopher Markus & Stephen McFeely)

Details: 116 pages – 1/21/11 draft

Awhile back, I heard that Michael Bay wanted to make a “smaller” more “personal” movie. Which was a little surprising. I mean this is a guy who was infamously quoted as saying, “I make movies so I can buy Ferraris” (which I can confirm is 100% true – I saw him out in one of these Ferraris once!). But you figure even the master of the ‘splosion would get tired of his 10,000th Transformer movie, even if they were paying him upwards of 100 million for each one.

So what does a “personal” Michael Bay film look like? Hmmm, well…you aren’t going to be getting Upstream Color 2, if that’s what you’re hoping for. If Bay can’t have big explosions, he’s going to have big somethings. And in this case it’s the big bulky frames of Mark Wahlberg and The Rock! You’re also going to have big soundtracks, like the irresistibly funky Top 40 hit, Thrift Shop! I guess we shouldn’t be surprised, then, that Bay’s smaller personal films are still basically big snazzy films, dressed down slightly.

Where Bay has always faltered in his movies, though, has been the script. He just doesn’t give a shit about it. Either that or he doesn’t understand storytelling. That’s what keeps him from the heights of guys like JJ Abrams, Peter Jackson and James Cameron. True, the Transformers movies have made a ton of money, but they’ve come at the cost of respect. Audiences just don’t take Bay seriously because his stories are a mish-mash of clichés, huge leaps of logic, and good old fashioned bad writing. They are the epitome of style over substance. One would think, then, that if he was telling a smaller story without all the pressures 250 million benjamins brings, that he’d like to get a little more into the story, a little more into the characters. Well, let’s jump in and see if that’s true.

The year is 1995. The town is Miami. The man is Daniel Lugo. Daniel Lugo believes in America. He believes in the notion that hard work pays off. And he’s chosen to do his hard work in the fitness sector, a place where he can milk his charm to make others believe that if they work hard enough, they can look just as big and strong and buff as him.

But Daniel also realizes that there’s a ceiling to what he does. There wasn’t any reality TV back in 1995, so you couldn’t turn your fitness charm into a Bravo show just yet. You worked your butt off 12 hours a day and you earned 50-60 Gs max. Daniel believes that America rewards you for your time. But that reward wasn’t big enough in his opinion.

So Daniel comes up with a plan. Why not kidnap one of his rich clients, kill him, and take all his stuff? Sure, sounds like fun to me. All he has to do is recruit his Mimbo trainer friend Adrian (The Rock) and a former drug addict named Paul Doyle (desperate to be a part of, well, ANYTHING). The three kidnap one of Daniel’s rich clients, Marc Schiller, a slimy piece of work who made his fortune fucking over all kinds of people, then try to kill him.

But the killing doesn’t go as planned and Schiller survives. Here’s the catch though. Schiller’s scared to provoke Daniel because Daniel knows about all his secret illegal doings. If he goes to the police, the police will just find out about all his criminal activity. Daniel figures this out and just moves into Schiller’s place and starts living his life. I mean, what’s to stop him? Eventually Schiller gets fed up, though, and hires a private investigator to collect evidence on Daniel’s shady doings so he can take him down in court. Daniel will probably survive the investigation if he lays low, but when he’s presented with an opportunity to take another high-flying businessman down, he lets greed get the best of him. And that’s when things really start spinning out of control.

Oh boy.

Okay, I want you to imagine Fargo………………..directed by Michael Bay.

Are you imagining that movie?

Okay, well, that’s the exact movie you get with Pain and Gain.

A story dependent on its intricately woven plot and characters directed by someone who doesn’t understand plot or characters.

Now I’m of the belief that there’s no single template for a good script, just as there’s no single template for a bad one. However, there are a number of things you can do to sway the odds in or out of your favor. Here you have a main character who’s kidnapping someone so he can steal all his money, after which he’ll kill him. Okay, got it. We’re rooting for a character to kill people for his own selfish interests. That’s typically not going to go over well with audiences.

Now this can sometimes work in a comedy setting IF the character doing the kidnapping is really funny. But that’s not the case here. At most you get a few hollow chuckles out of Daniels’ antics. There’s a mastery of tone required in this situation, tone that bounces back and forth between seriousness and humor, that is so hard to pull off. It’s a tone the Coens have perfected over time. And it’s something so alien to Bay that I’m surprised he chose to do this film in the first place. I mean, is Bay a secret Coen Brothers fan?

Another problem here is that there are only two interesting characters, Daniel Lugo and Marc Schiller. Daniel works because he’s a walking hypocrite. He says he believes in America and working hard, yet he’s constantly looking for the shortest shortcut to the top. Schiller works because he’s over the top and fun. But everyone else here is boring as hell. I mean The Rock’s character (Adrian) has absolutely nothing going on. He just jumps whenever Daniel says jump. Ditto Paul Boyle, whose only twist is a barely-there drug addiction. The reason this matters is because the script presents itself as an exploration of a bunch of wild weird people caught up in a crazy plot. But there were only two wild and weird people worth watching. Everyone else was boring.

Then there were just things that didn’t make sense. Schiller wanted his life back but couldn’t tell the police because he had too much to hide. So he hires a private investigator to put a case together against Daniel stealing his life. But wait a minute…If he’s putting together a case against Daniel, wouldn’t he eventually have to go to the courts to get his stuff back anyway? Doesn’t that put him in the same position he was in from the get-go? Having to go to the cops? Since that didn’t make a whole lot of sense, and since most of the plot rode on the assumption that it did, you just didn’t care much what happened. When you add on top of that the fact that you hated everyone in the movie, both bad guys and “good,” there wasn’t much left for Pain and Gain to offer.

This script was a hot mess!

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Instead of using “We see,” try to convey your imagery and action through description. Pain and Gain opens with our main character doing sit-ups on a roof. The description reads like so: “He crunches toward his knees and sees the parking lot. When he lies back down, he sees the sky. – Up, parking lot. Down, sky.” With this description, we can tell what the camera is doing (showing the crunches from Daniel’s POV), without physically saying, “The camera shows…” or “WE SEE the parking lot from his point of view, then the sky as he comes back down.” The reason this is important is because it keeps us inside the story. The second you say “POV” “the camera” or “We see,” you remind the reader that they’re reading a movie. Now I still see professional writers using these terms (especially writer-directors, who like to write specific shots into their scripts), and they’re by no means script-killers. But, preferably, you want to be as invisible as possible about your script being a script. You can’t whisk your reader away if you’re constantly reminding them that they’re reading a screenplay.

Author Ira Levin’s book about a woman impregnated with Satan’s child was deemed so commercial that legendary producer Robert Evans snatched up the rights before the book was even finished. He then recruited European director Roman Polanski to write and direct the film, which would become Polanski’s first foray into American cinema. Polanski wanted his wife, Sharon Tate, to play the part of Rosemary, but Evans convinced him to go with Mia Farrow, despite the fact that her husband at the time, Frank Sinatra, wanted her to quit the profession. In fact, when she officially accepted the part, he filed for divorce. The film’s adapted screenplay went on to get nominated for an Oscar and was a huge box office success, grossing ten times its budget. Some, however, believe that because of the movie’s subject matter, its principal participants were cursed. Polanski, of course, lost his wife in the Manson murders, then later sexually assaulted a young girl, forcing him to flee to France and never set foot in America again. And Mia Farrow, after being left by Sinatra, eventually married Woody Allen, which of course ended in tragedy when she found out Allen was having a sexual relationship with her adopted daughter from a previous marriage. Regardless of all that, Rosemary’s Baby is one of the best movies from the 60s, and therefore ripe for its share of screenwriting tips.

1) The Villain Goal – I often talk about giving your protagonist a goal, as that goal will drive the story. However, if your protagonist doesn’t have a goal, you can transfer the goal over to the story’s villain. That’s the case with Rosemary’s Baby. The story is being driven by a goal held by Rosemary’s elderly neighbors, Roman and Minnie Castevet. The two need a woman to carry Satan’s baby. And she’s been chosen.

2) DRAMATIC IRONY ALERT – Remember what Dramatic Irony is. It’s when we know something one of the key characters does not. And it works best when the thing we know is something that puts our character in danger. Almost all of Rosemary’s Baby is based on this device. We know that she’s carrying the devil’s baby and that all these people around her are manipulating her, but she doesn’t. We want to scream, “Run! Get away from everyone!” which is usually when “dramatic irony” is working best.

3) Look for your scares using human psychological elements – When most writers think about scares, they think of the cliché stuff. Ghosts, demons, witches, etc. Rosemary’s Baby is a horror film without any real “scares.” Its horror comes from its psychological nature, the fact that Rosemary is being manipulated. To me, the scariest situation of all is when the person you’re supposed to trust the most deceives you, which is a big part of why this movie works so well. Rosemary’s own husband has sold her off to the devil. If you can’t trust your own spouse, who can you trust?

4) When writing a horror film, jump into your mysteries right away – You need to hook your reader immediately in a horror script, and one of the best ways to do this is to introduce a mystery inside the first couple of scenes. Here, we see it when Rosemary and her husband, Guy, are checking out the apartment. They discover an armoire hiding a closet. Keep in mind, this is the 60s. If the screenwriter is jumping right into the mysteries in a 1968 film, you better hope you’re doing it in 2013, where audiences are 10,000 times less patient.

5) Contained movies require writers adept at adding conflict – Remember, when writing a contained film (almost all of Rosemary’s Baby takes place in an apartment), you need to add AS MUCH CONFLICT AS POSSIBLE. You do this in three main areas – internal level, relationship level, and external level. On the internal level, Rosemary battles with her desire to make everyone happy, even though inside everything’s telling her to look out for herself. That line of conflict stays present throughout the entire movie. On the relationship level, Rosemary is having marital issues with her husband, Guy, who seems to be putting his career ahead of Rosemary. This causes lots of conflict during their time together. And of course, externally, Rosemary is battling the invasion of her elderly neighbors, who are trying to control her life. Conflict should be present in all your films, but you better PACK IT IN if you’re writing a contained film.

6) Nice Villains Finish First – I continue to believe that nice villains (when done right) are the scariest villains of all. Asshole cruel dickhead terrible villains are often cliché and boring. Whereas there will always be situations where scary or “clearly bad” villains are necessary (i.e. Buffalo Bill wasn’t very nice), nice villains should at least be considered when writing your script. Here we have neighbors Minnie and Roman Castevet, who have orchestrated the rape and manipulation of our heroine, Rosemary. But they’re always there for her with a smile. They’re the first people to help here whenever there’s a problem. This movie just does not work if these two are forceful and mean and clearly cruel.

7) Don’t let your protagonist be wimpy for too long – In this kind of movie, everything is predicated on our character being duped. So for a good portion of the movie, the protagonist must play that role. But if this goes on for too long, we start to get frustrated by the character, sometimes even turning on them. We don’t like characters who don’t do anything to change their shitty circumstances. So at some point (usually in the second half of the second act) the protagonist should start rebelling. Here, it’s when Rosemary throws her own party. From that point on, Rosemary begins making her own decisions, as opposed to letting the decisions be made for her.

8) Build up suspense by allowing your audience to see their presents the night before Christmas – Waiting for the horror to finally arrive is one of the more enjoyable aspects of watching a horror film. But it’s a lot more fun when the writer teases that horror. It’s kind of like getting to touch and lift and shake your gifts the night before Christmas. It gets your mind spinning, excited and curious about what could be in those boxes. Here we get the armoire blocking the closet. We also get Rosemary’s friend, Hutch, warning her about all the strange deaths in her building. We see it later in the first act when Rosemary’s new friend seemingly commits suicide by jumping to her death. These moments are just like getting to hold and shake those unwrapped gifts. They make us eager to see what’s inside.

9) Whoever has the goal that’s driving the movie (even if it’s your villain) should encounter obstacles along the way – This is important to remember. When your hero is driving the movie with their goal, what makes their journey interesting are all the obstacles they encounter along the way. This same approach must be applied if your villain is the one driving the story. Since our villains’ goal is to guide Rosemary through her pregnancy so she has a healthy baby, Polanski creates ways to foil that plan. First, Rosemary’s friend Hutch shows up, who becomes suspicious of Rosemary’s neighbors. Then later, Rosemary insists on throwing a party with all her old friends, friends who could conceivably convince her how strange her pregnancy is. Regardless of who has the goal in your story, they should always encounter obstacles.

10) Go against the obvious with your horror ending – Again, most writers believe that a horror ending has to be the grandest scariest freakiest craziest spookiest scenario possible. As a result, a lot of the endings to horror scripts end up being similar. What separates Rosemary’s Baby and a big reason it’s such a classic, is that it does the exact opposite with its ending. Rosemary walks through a brightly lit apartment with people everywhere, sitting and talking in very non-threatening ways. Nobody really says or does anything when they see her. She’s allowed to be in the room without retaliation. What makes it so spooky is just how un-spooky it is!

These are 10 tips from the movie “Rosemary’s Baby.” To get 500 more tips from movies as varied as “Aliens,” “Pulp Fiction,” and “The Hangover,” check out my book, Scriptshadow Secrets, on Amazon!

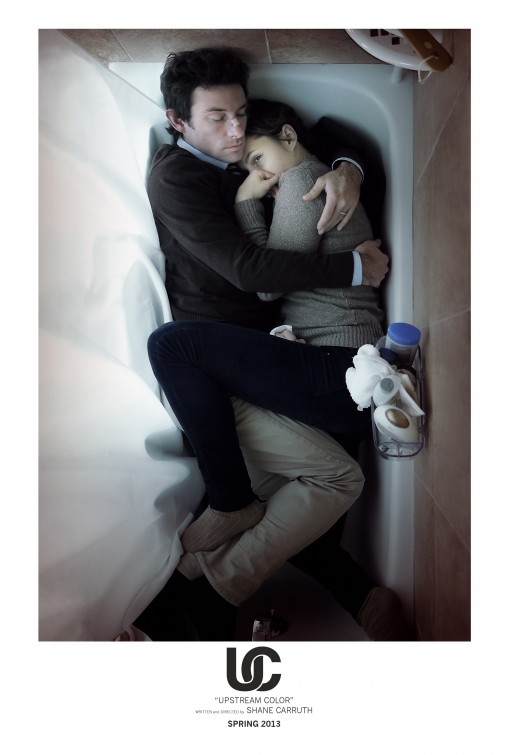

Genre: Drama

Premise: A woman is kidnapped, drugged, and robbed of her life’s savings. She must now figure out how to reclaim her life, a task made easier when she meets a man on a train. Plus there are pigs.

About: Shane Carruth became a breakout sensation in the filmmaking world a decade ago when his first film, Primer, shocked Sundance and became the Grand Jury Prize Winner. The time-travelling mind-bending thriller shot for under 10 grand gave young filmmakers everywhere hope that they, too, could shoot films on the cheap and become star directors. But in the years after, Shane’s inexperience with the Hollywood system led him to dead end after dead end, unable to put together another movie. He then shocked the film world (once again) when this new film of his showed up at Sundance this year, a film no one knew he had even made. Carruth wrote, directed, and starred in the movie.

Writer: Shane Carruth.

Details: 97 minutes

Upstream Color was one of the most frustrating movies I’ve ever seen. It was a movie designed to destroy you, to make you detest it. It challenged you to be the one person in the theater who came away saying, “I liked that.” Even still, if you managed to be that person, you didn’t know why you were that person, why you liked it. Or maybe you did. Maybe you convinced yourself you did. Like Carruth’s first movie, Primer, it’s a film that makes you feel smart if you can follow along. It makes you feel superior. It’s a recipe that Carruth’s used to gain his cult following: Make the puzzle complex enough so that you feel good if you can put it together.

But there’s a difference between being a skilled puzzle maker and just throwing a bunch of pieces on the screen. In fact, I think there are many parallels here to Shane Carruth’s career and Richard Kelly’s. Both broke through with these strange puzzle-centric stories and made them jusssst weird enough that you weren’t sure if their intrigue was created on purpose or the result of pure luck. Kelly’s mess of a second film, Southland Tales, proved that it was probably the latter. And Upstream Color, in my opinion, proves the same.

Let me give you some background here. Keep in mind I heard this through the grape vine. It’s by no means fact. But I did hear it from a couple of independent sources so I’m willing to believe it. Shane came out of Primer with Hollywood in the palm of his hands. Everyone wanted to work with him. They tabbed him a young Kubrick. So Shane went around pitching a half thought-through idea about some marine biologists that was part drama, part romantic comedy, part sea adventure, etc. Nobody really understood what the movie was about so Shane went back and wrote this script called “A Topiary,” about kids who used star burst energy to create and control flying dragon-like creatures.

It was 244 pages long. (for those who are mathematically challenged, that would be a 4 hour movie)

Despite this, Shane had some big people who wanted to help him. How big? Try David Fincher. Fincher wanted to shepherd his career, guide him along, produce his films. So Shane showed him his script and then waited for the money. Except Fincher (and others) had some problems with the script. It was long and wandering and devoid of drama. They wanted to give Shane notes. Shane was SHOCKED. Shocked! I mean, are you serious? You’re not just going to give me a hundred million dollars without any strings attached and let me make my movie??? And thus began why Shane Carruth hasn’t made a movie in ten years. Cause he told guys like David Fincher to go fuck themselves.

Now some of you might be holding up your fists and screaming, “you go, girl.” “Fuck Hollywood.” Except David Fincher isn’t just anyone in the land of smog and billboards. Fincher notoriously went through hell with “the system” when he made Alien 3. It’s something that still affects him today, and why he tries to stay somewhat outside the system even as he’s working within it. In other words, Fincher is one of the few people who actually understands what it’s like to be in Shane’s shoes. He’s sympathetic. So if Shane’s having trouble with this guy, I can only imagine how he rubbed everyone else.

Now the reason I bring this up is because Upstream Color plays like a movie that nobody else but Shane has seen. You know how you screen things for friends or let friends read your scripts so that you can iron out the things that don’t make sense? Things that don’t seem to be playing the way you intended them to? This film didn’t go through that process. Or if it did, Carruth ignored any and all feedback. Because the storytelling here is a mess. It’s like the ultimate experimental student film. Zero script and a bunch of experimentation.

So what is it about? Well, I needed to consult with a few other people to come to this summary, but here’s the best I could do. There’s this woman, a film editor or something, I think. She gets kidnapped by this guy who’s created these “drug-worms,” little maggots infested with some sort of mind-control chemical. Once swallowed, the victim basically becomes a mental slave. The guy who kidnaps her then tells her to clear out all her bank accounts and give him all the money. She wakes up a few weeks later, having no idea why she’s broke and can’t remember anything.

But that becomes the least of her worries when she notes a worm swimming through her body up around skin level. She tries to keep cutting it out but with no success. She then hears a noise, a loud “WOOOMP WOOOMP” that draws her from her home out to a pig farm. She tells the strange pig farmer that she can’t get this worm out. No problem, the pig farmer says, and performs surgery on her, inserting (I believe) some pig parts inside of her. This seems to eliminate the problem. Or so we believe.

The woman then wakes out of her mental stupor, realizing that she’s lost her job and that a couple of months have gone by. As she attempts to put her life back together, she meets a dude on the train who has a sketchy (potentially illegal) hotel job. Sketchy Hotel Guy takes a liking to the woman and keeps asking her out. But because the last dude she met led to worms and pig parts inside her body, she’s understandably reluctant. Eventually, however, his persistence pays off, and the two start dating. Except this is REALLY DEPRESSING DATING. Like, both of these people have extremely mundane boring lives and talk about the most boring things imaginable. So we must endure banal, directionless, sad dialogue between them for many many scenes.

Eventually, Sketchy Hotel Guy realizes that Pig Girl isn’t all mentally there. Clue number one is that she likes to take a bag of rocks to the local swimming pool, dump them on the swimming pool floor, recover them one at a time, reciting lines from an obscure book while doing so. Observing this, it occurs to Sketchy Hotel Guy that the two of them might be under some mind control. So he and Pig Girl do some investigation, locate the pig farmer, go to his place, and realize that each of the pigs he owns is some sort of psychic counterpart to a human being out there in society. Which means they’ve both been psychically pig-abducted. I think. They then go out, tell all of the psychically abducted pig people that they’re being controlled by pigs, and those people come to the pig farm to look at their pig counterparts, coming to terms with the reality that they’re… sorta pigs too, now. Then they all go home and order pizzas with extra pepperoni (okay, I made that last part up).

Okay, I’m just going to state the obvious here. This idea is dumb. I’m sorry, but it’s just dumb! Psychically controlled pig people? There’s no screenwriting gobbledy-gook that needs to be mentioned or applied here. It’s just a DUMB IDEA. I don’t care how you dress it up. You put lipstick on a pig, it’s still a pig. Someone needed to tell Shane Carruth that this was a dumb idea and to not to make this movie! But, see, Shane Carruth isolated himself from Hollywood so that nobody could tell him no. He’s like the indie version of George Lucas.

I mean, nothing really matters if the idea is stupid, right? If people aren’t on board with the idea, they won’t give a crap about the story. Except for the rare case when you get a really awesome storyteller who can make a bad idea interesting. Shane Carruth, however, is not that storyteller. You’d have a better chance translating Mayan scripture than one of his stories. And some people think that’s by design. I don’t. I believe that the success of a storyteller is dependent on the audience understanding his work in the way he intended for it to be understood. If he’s trying to make you see “A” and you’re seeing “B,” that’s a failure. And I don’t think anyone but a scattered few are interpreting Shane’s work the way he intended. And this could’ve been avoided by simply – oh I don’t know – LISTENING to other people. Other people’s opinions are not the devil. You don’t even have to make the changes they suggest. Just LISTEN to them. If you did, you might be able to make more than one film a decade.

Personally, I think the movie would’ve been better if the guy who kidnapped her originally (who hypnotized her so she wouldn’t remember who he was) was the one she later started dating, instead of Sketchy Hotel Guy. I mean, now you have some actual dramatic irony. We know this guy is dangerous, that he’s stolen this woman’s money, and she’s falling in love with him. That’s a scenario I would’ve been intrigued by.

But there’s nothing as skilled as that here. It’s all just strange ideas mixed in with an awkward romantic relationship storyline. I did like a few things. I liked the title. I liked the cinematography. I liked the score. The first few minutes of the movie were captivating in a purely cinematic way. But it always comes back to the story for me. If you don’t know how to dramatize situations, how to add suspense or create compelling relationships or clear conflict. Or just make sense! You’re going to fall on your face. And Upstream Color, along with all the little piglets it birthed, falls squarely on its face.

[x] what the hell did I just watch?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth watching

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Dumb ideas make bad movies. I know this sounds obvious but I see a TON of scripts that are doomed before I even read the first line because the ideas are dumb. Simple test. Throw your idea in with a bunch of others, send them to some friends, don’t tell them which one is yours. Ask them to rank the ideas from best to worst. If your idea isn’t coming out near the top, don’t write it. Or just pitch your idea to people. Regardless of what they say (they’re all going to tell you they “like” it to be nice to you), look at their eyes. Are they excited, or are they confused and bored? A sign of a good idea is when they jump in and start adding ideas. Or they’re just excited. If someone looks genuinely excited about your idea, you know you have something good.

This is your chance to discuss the week’s amateur scripts, offered originally in the Scriptshadow newsletter. The primary goal for this discussion is to find out which script(s) is the best candidate for a future Amateur Friday review. The secondary goal is to keep things positive in the comments with constructive criticism.

Below are the scripts up for review, along with the download links. Want to receive the scripts early? Head over to the Contact page, e-mail us, and “Opt In” to the newsletter.

Happy reading!

THRILLER WEEK!

TITLE: Eden Burning

GENRE: Horror / Psychological Thriller

LOGLINE: An ostracized teen struggles to clear his name of the grisly murder he allegedly committed as a child and clashes with a mysterious, malevolent entity hell-bent on stopping him.

WHY YOU SHOULD READ (from writer): “Eden Burning” has received attention from a number of small production studios — one of them refers to the script as their “The Butterfly Effect.” Honestly, I’m more concerned with developing my craft right now. I’m a longtime fan of ScriptShadow and I’ve dreamed of having the community dissect one of my scripts. Take a look, I promise you’ll be entertained.

TITLE: The Transit of Venus Jones

GENRE: Sci-fi / Thriller

LOGLINE: A woman discovers that her robotic boyfriend is a real man – a fugitive on the run – who will take her on the ride of her life as they battle the eerie technology of the not-so-distant future.

TITLE: The Intake

GENRE: Psychological Thriller

LOGLINE: Her once unflappable confidence shaken by a client suicide, a university therapist takes on a new young client who pushes her therapeutic and ethical buttons – with eerily accurate descriptions of murders that are not public knowledge.

TITLE: False Flag

GENRE: Action/Thriller

LOGLINE: C.I.A. agent Sean Murray is ordered to carry out a false flag op on American soil. His life, and America, will never be the same.

TITLE: Frame-Up

GENRE: Action/Thriller

LOGLINE: Drugged with a roofie at a fraternity party, an innocent freshman wakes up next to a murdered man. Now she’s on the run from the police, while she tries to outwit the spy organization that is framing her for the crime.

Amateur Friday Submission Process: To submit your script for an Amateur Review, send in a PDF of your script, a PDF of the first ten pages of your script, your title, genre, logline, and finally, why I should read your script. Use my submission address please: Carsonreeves3@gmail.com. Your script and “first ten” will be posted. If you’re nervous about the effects of a bad review, feel free to use an alias name and/or title. It’s a good idea to resubmit every couple of weeks so your submission stays near the top.

Genre: Horror/Comedy

Premise: (from writer) When the girl of his dreams is kidnapped by a legion of monsters and her sorceress-possessed father, a timid teen must rally his misfit friends and faithful mummy to save his crush before her sacrifice unleashes Armageddon.

About: Day 2 of The Smackdown is here. The rules are simple: Two scripts enter, one script leaves. Why is this happening? A couple of weeks ago, you guys voted on the best of the 5 Amateur Offerings. But the votes were too close to count. So instead of picking one, I decided to review both – The Turning Season was yesterday. And Monster Mash is today. Who’s going to win? That’s up to you!

Writer: Daniel Caporetto

Details: 102 pages

When I imagined the Smackdown in my head, it made a lot more sense. Two horror scripts duking it out for Week of April 8th supremacy on Scriptshadow. How could it go wrong? But now that I’ve read Monster Mash, I’m not sure I’m down with the Smackdown. These scripts couldn’t be more different. Turning Season bobs where this weaves. It ducks where this dunks. We’re comparing a heavy horror drama to a goofy horror comedy. Emotion vs. laughs. Can such a thing be done?

Well, let’s start by asking the big question: Was Monster Mash funny? Let me answer that question this way. If you’d told me this was from the same guys who wrote Harold and Kumar, I probably would’ve believed you. So that’s something. The problem is, lots of folks will say that that’s not a good thing. I’d respond by saying writing a goofy script that actually works is hard as hell. It’s such a fine line between funny and stupid. I mean we have zombies giving hummers and mummies RECEIVING hummers here. High-brow this ain’t. Yet for all its craziness, I think it achieves what it’s trying to do.

Our story begins back in the Egyptian ages n shit. No idea how long ago that was but we’ll say 3000 years, give or take like…3000 years. A Kim Kardashian-looking Egyptian princess, Manzazuu, is going about her daily routine, trying to sacrifice her daughter to the Gods for eternal power or something like that, when her hubby comes flying out of nowhere demanding she stop. She refuses so he chops off her head. Apparently domestic dispute laws were really lax back then.

Cut to the present where 18 year old slacker Will is trying to figure out a way to snag school hottie Sandra from her asshole jock boyfriend, Mark. It’s actually working, as Sandra seems to like him, but for whatever reason, he can’t seal the deal. The good news is, there’s a Halloween party tonight, and he, along with his best friends Chuck (vulgar asshole) and Dom (really long bangs) are going to go there to sort their female problems out.

Unfortunately, across town, a new package has just showed up at the museum. A package of DEATH!!! Okay, maybe that’s an exaggeration. It’s an Egyptian exhibit. But this exhibit is a teensy bit more interactive than the museum is prepared for. That’s because a couple of short mummies pop out, and a scepter-staff thing channels a long ago power that possesses an overweight worker named Tim. And guess who the possessor is? That’s right: Manzazuu! She’s back. In a severely out-of-shape man’s body!

Manzazuu’s first order of business is to secure an army. So she raises the dead, infesting the local town with lots of zombies. She also sends out her wolf guards to find Sandra, as Sandra happens to be her great great great great great great great great great great great grand daughter or something, which means Manzazuu can sacrifice her to raise the serpent God of Death, who will, of course, help her destroy the world.

This means Will, Chuck, Dom, Dom’s crush (male-energy Lila), and one of Manzazuu’s zombies they’ve converted, must suit up, arm themselves, and get to the museum to stop this sacrifice, all the while working through their problems with each other.

If I worked at a production company and someone asked me point blank, “What did you think of Monster Mash?” my response would be something like, “It wasn’t bad. It moved quickly. It had some funny moments. The guy knows how to write. But it was just too goofy for my taste.” “My taste” is the operative phrase here. I’m not 21, though I have a feeling I’d be a lot more into this if I were. That’s the tough thing about judging a script that isn’t your cup of tea. You have to guess what the target demo will think of it. And my guess is that they’d like Monster Mash.

I mean there’s some funny stuff here. When Manzazuu comes back in the body of a middle aged overweight man, yet still dresses like Kim Kardashian… that was funny. When the Chubby mummy can’t talk and therefore communicates via charades…that was funny. The mummy getting sexually molested by the high school slut…that was funny. The script kept a good stream of laughs coming.

But in the end I just wanted more from these characters. I don’t even know if this feeling is relevant anymore because I DO see a lot of professional comedy scripts that ignore character development. But I’m of the belief that if you make us believe in and care about your characters, that their escapades are going to be that much funnier, because we’re always more emotionally invested in people we care about.

Caporetto DOES make some inroads into this department, or at least tries to. Sandra’s dealing with the loss of her mom, for example. But for the most part, it was a bunch of surface level kids without a care in the world. If you look back at The Hangover, you’ll notice how intensely the stakes were set up. That wedding meant everything to Doug’s fiancé. And it meant everything to Doug himself. So when Doug gets lost, we know how important it is for them to get him back to his wedding on time. It’s not like Doug woke up in the opening scene trashed out of his mind with two hookers on his side. That scene might’ve been funny, but it doesn’t make us care about Doug. You’re just playing with fire when the pillars of your story are jokes.

On top of that, those pillars need to be clear. For example, I couldn’t figure out the relationship between Sandra and Will. She clearly likes him. There’s even an implied history there (they used to be together??). Yet he’s afraid to tell her he likes her? Why would he be afraid when she’s practically throwing herself at him? That whole relationship just needed to be better defined. I probably would’ve had Sandra more openly rejecting Will, making his job a lot tougher.

I also don’t like when different relationships in a movie tackle the same problem. Will’s wondering if Sandra likes him. And Dom’s wondering if Lila likes him. It’s the same thing and therefore lazy. Have Dom’s problem be something different. Maybe he’s trying to BREAK-UP with his girlfriend of two years, but she won’t let him. Anything so that two of your main characters aren’t tackling the exact same issue.

Some of this laziness crept in to other parts of the script as well (two of our main four characters have parents who work at their high school). It’s a little too neat, too cozy. And it’s not to say these things are script-killers. But they’re things experienced readers notice. They want to know that you, the writer, have exhausted every choice before deciding on one. And if the parents of two of your main characters are both teachers, that implies you’re not really trying that hard.

Monster Mash is one of the better scripts I’ve read in this genre in awhile, which is a tough genre to write. But personally, it was too goofy (and not deep enough) for me. I wanted to latch onto these characters as opposed to simply observe their antics. What did you guys think? Am I being too harsh? Should I not take this too seriously and loosen up? Oh, and which script won the Smackdown?? It was close, but I’d cast my vote for The Turning Season.

Script link – Monster Mash

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Make sure each character has a problem independent of the story. In other words, if none of these crazy mummies and zombies had showed up, would your characters still have an issue they had to overcome? The answer should be yes. Here, Will is trying to get Sandra. That’s his problem he needs to solve. It’s not done very well because Sandra appears to already like him. But the idea behind it is good. Try to do this for EVERY character. Give them a problem independent of the story. That way, parallel to solving the giant overall goal, they’re trying to conquer these smaller more personal goals.