Search Results for: the wall

Today I use this wild thriller to teach you how to write better action sequences.

Genre: Thriller

Premise: When a crossword puzzle maker finds out his dead father hid a code inside of him, he must figure out what it means before a pissed off CIA finds him first.

About: I keep seeing this name in the trades wherever I turn. “Joby Harold.” He wrote the King Arthur remake. He wrote the new upcoming Robin Hood movie. He just signed on to rewrite DC’s new Flash movie. “Who is this writer??” I’ve been saying every time I see him. A little research shows he wrote and directed the Hayden Christensen movie, “Awake,” back in 2007. But he hasn’t done much since. I traced his re-rise back to this script, which he wrote in 2011. Let’s find out why this got him back on Hollywood’s radar, and led to him being one of the hottest screenwriters in town.

Writer: Joby Harold

Details: 114 pages – 2011 draft

This week’s going to be fun. Tuesday through Friday I’m going to review the Top 4 scripts from the Scriptshadow Tournament, with the winning script, The Savage, getting the final, Friday, review.

But that leaves an open slot for today. And while I’d love to use that time to discuss the box office battle that was Split versus A Dog’s Purpose, I’ve opted instead to figure out where Joby Harold came from.

Whenever you’ve got a guy tearing up the assignment circuit, you want to know what their secret is. I’ll save you the suspense though, since I already know the answer. You get big assignments in a genre because you wrote something good in that genre. This is an actiony thriller script. He’s writing actiony blockbuster scripts.

But what about the content? What’s inside this script’s walls? Is it good? Will it help me forget my unhealthy obsession with the Split versus A Dog’s Purpose box office battle? I hope so.

Jake Richmond lives a quiet existence in San Fransisco writing crossword puzzles for The San Fransisco Post. He’s divorced with a young daughter, Emma, who’s the apple of his eye. Unfortunately for Jake, his past is a rotten apple. He was found on a boat when he was a toddler and has no idea who his parents are.

Then one day, while riding on the subway, an old man notices the unique cross Jake has around his neck, the cross that was found on him as a child. He lets Jake know how rare the cross is and encourages him to come to his museum to learn more about it.

Jake does, reluctantly, and it’s there that the man finds a little trap door within the cross, where a teensy-tiny scroll comes out. On that scroll? A phone number! They call it, where a 35 year old message tells him who his parents were and that Jake’s carrying something valuable inside his body.

The lousy news is, the CIA stole the device designed to receive that call, and they want to kill Jake just like they killed Jake’s dad! Why? We don’t know yet. But we get the feeling Jake knows something big. Or, at least, he will once he pieces together the puzzle his dad left for him.

That puzzle leads him all across the United States solving all sorts of weird puzzles. For example, at one point, Jake has to cut himself open to receive another clue, which is a long string with tiny knots in it. Those knots? They’re morse code, motherfucker!

On another occasion, Jake is given a series of directions that takes his car in every which way, making dozens of turns that make no sense. That is until after he gets to the destination – a storage facility – and needs to know what number locker to open. Zoom out. The number was traced via the path he just took with his car!

All the while, Jake is being followed by a mysterious CIA operative named Mr. Poe, who has a creepy Marathon Man-y vibe to him. Jake’s only hope of surviving this chaos is to find out what his dad was hiding from the CIA and use that knowledge to bargain for his life.

The Key Man is an old-fashioned mystery-on-the-run thriller. And mystery-on-the-run-thrillers are tough to write because there are only so many ways to write the “on-the-run” stuff, and the “mystery” stuff requires a hell of a lot of intelligence and creativity to come up with anything fresh.

Typically the way these scripts work is they start off with one good puzzle component, then each subsequent component gets cheesier and/or dumber. And that’s because we, as writers, are inherently lazy. So with each subsequent mystery, we’re less motivated to write something as good as the last one.

The initial component in The Key Man is that the first clue’s been surgically implanted inside Jake’s body. This leads to the best set-piece of the script, which is Jake holding a nurse hostage and making her perform surgery on him to retrieve the clue.

Unfortunately, this is where the mysteries go downhill. A string with knots acting as morse code felt a little… I don’t know, far-fetched? And then we’re deciphering that code to come up with a long string of numbers and letters, which we eventually learn are directions (the letters are direction and the numbers the number of blocks to go).

Look, I’m not going to rail on Harold here. I’ve tried to write these things myself and they’re really fucking hard. If you can come up with a COUPLE of good clues/mysteries, you’re doing a good job. But these scripts have 7 or 8. And unless you have the endurance to stick those out and be creative with each one, you’re not going to write anything good.

And really, this is a lesson for every genre. One of the biggest reasons that bad screenplays happen is lack of effort. The writer knows their choice for this next scene or this next sequence isn’t great, but they tell themselves, “It’s good enough.” Once you start using that phrase (good enough), you’ve lost the battle.

Another thing I want to bring up here is the difference between simple action and structured action. Simple action is straight forward, no brains necessary, action. This is how The Key Man starts. We’re following this couple and their child as they run from the CIA. However, THAT’S ALL THAT’S HAPPENING. It’s linear, it’s straightforward, it doesn’t require anything from the viewer.

Structured action is when a story is built into the action. There are multiple threads going on or a complex problem involved or a character conflict that’s agitating the scene, or all of the above. Audiences like structured action because it ENGAGES them on more than just a “look at all the flying colors” basis.

A good structured action scene is the plane crash in the movie, Flight. Before there’s even a problem, you have a drunk pilot. That adds complexity to the issue. Next you have a set of broken hydraulics, which make it impossible to control the plane. Then you have a young co-pilot who’s freaking the fuck out. So we gotta calm him down. Then we realize that the only way to save everyone is to pull off an impossible flight maneuver that’s never been attempted before (turn the plane upside-down). There’s no guarantee that will work. So it’s an all-or-nothing proposition.

You can tell that this crash sequence has been THOUGHT THROUGH. There are things going on on multiple levels, giving the scene a three-dimensional structure. The simple action version of this scene would’ve been, one pilot, an engine problem, and an attempt to make an emergency landing. And that would’ve been it. I suppose it could’ve worked. But how exciting would that have been?

Anyway, getting back to The Key Man. This script had some fun moments but it never rose to a level that allowed it to overcome this conceit: a father leaves his son a dozen impossible-to-solve puzzles to find what he left him. Why not just put the answer in the initial necklace note and call it a day?

Of course, you could make a similar argument for movies like National Treasure. So maybe the problem’s me. I crave a more sophisticated and believable puzzle to get me going these days.

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Almost all of your action scenes should be STRUCTURED. What I often find is that the writer will structure THEIR MOST IMPORTANT action scene (so the featured plane crash in “Flight”) and then go with simple action scenes the rest of the way. Take the extra time and structure ALL your action scenes. I promise you your script will be better for it.

Today’s writer makes one of the snazziest minor innovations to the screenwriting format I’ve seen since I started reading. This needs to become a mainstay in all scripts going forward!

Genre: Western/Thriller

Premise: When a poor but ambitious family man finds a barrel of gold, he attempts to follow his dreams without allowing his greed to drive him insane.

About: This script finished in the middle of the pack on last year’s Black List. These days, many Black List scripts come already optioned or purchased, or, at the very least, campaigned for. Let the Evil Go West is one of the few scripts that made the list bare naked. That implies that it was passed around due to the quality of the script alone – a rarity. Screenwriter Carlos Rios is an alumni of Universal’s Emerging Writer’s Fellowship, which is becoming a hotbed for finding strong emerging talent.

Writer: Carlos Rios

Details: 117 pages

One of the things you become keen on when you read a lot of scripts is knowing when you’re reading a writer and when you’re reading a pretender. The pretender is like the annoying guy at the party. He’s got nothing of substance going on so the only way to get your attention is to yell and scream and jump in the pool several times.

On the flip side, good writers are like Andy Warhol. They’re so confident in themselves that they’ll stand in one place, barely say a word, and let the party come to them.

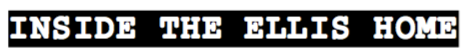

Let The Evil Go West is one of the coolest written scripts of 2016. I LOVE this guy’s style. First off, he grounds that style in the format’s most dependable approach – SIMPLICITY. His writing is descriptive, but always stays on point, rarely eclipsing 3 lines.

On top of that, he uses a “continuous style.” A continuous style continues sentences and paragraphs even after a line break, sometimes bypassing capitalization in order to keep your eyes moving.

It’s a best of both worlds scenario. The only benefit of “wall of text” writing is that the sentences visually connect one after another so it feels like one continuous thought. The problem with walls of text is that they’re daunting and readers feel overwhelmed by them.

With a continuous writing style, we jump down to a new paragraph, and yet we’re still within the same thought, action, or description. However, we don’t have to deal with the cumbersome mass of text that usually accompanies that kind of connective writing.

Rios is a such a snazzy writer, he even innovated the format. More on that in a second. But first, let’s learn what this script is about.

30-something Abner Ellis is a lot like Daniel Plainview from There Will Be Blood. He’s an ambitious man who wants to take advantage of a country that’s still in its infancy. He’s got a beautiful wife, Elspeth, and a handsome little boy, Benjamin, who he plans to bring along on this journey.

The problem is, Abner is poor as shit. And back then, the only way to make money was to have money (actually, that hasn’t changed). Unfortunately, Abner’s been stuck in a string of low-paying jobs that eventually brings him to the Trans-Continental railroad.

While working for 2 dollars a day clearing land, Abner lucks out when he finds a barrel of gold in the nearby forest. Sure, there are four dead men laying by it, all of whom killed each other over the stash. But that’s the last thing on Abner’s mind. He’s finally in the game.

Abner moves his family up to Wyoming where he puts his grand plan into motion. Abner will build an entire town that the brand new railroad will run through. Elsbeth isn’t so sure, but Abner’s dogged determination to make something of his life eventually convinces her.

There’s one problem. Abner’s losing it. He’s so obsessed with his barrel of gold and so convinced that the next guy is around the corner, plotting to steal it, that he becomes more protective of it than he does his own family. And when real threats do surface, he’ll do anything to keep his gold. Even if it means killing those closest to him.

You’re dying to know what that innovation is, right? Okay, let’s do it.

One of the annoying things about reading is the inefficient syntax that delineates DAY from NIGHT at the end of a slugline. Most of the time, readers shoot past slugs to get to the important stuff, and often become confused as a result, needing to back up and check what the slug said to gain context. DAY and NIGHT are just one casualty of this glitch.

So Rios REVERSE BLOCKS his nighttime slugs. This way, we get an instantaneous VISUAL CUE that it’s night time. It’s genius! This was the first script I’ve read where I instantly knew whether it was night or day without having to read anything.

Now if someone could invent a visual slug that also delineated EXTERIOR and INTERIOR we could streamline screenwriting forever and push these janky math-like documents one step closer to a natural storytelling medium.

Well that’s great, Script Nerd Carson. But what about the script?

The script was great. There were so many hallmarks of good storytelling here.

Start with Abner. Scripts work better when the main character has a strong drive. Not only do we like people who are driven more than those who aren’t, but driven characters create a natural reason for us to keep reading. We want to see if the character is going to achieve what they’re driven to do.

Abner wants nothing more than to become great. So we want to see if he can do it.

Contrast that with a character who’s fine with where he is in life. Maybe something terrible happens to him and that’s what begins his story. You can still write a good script this way, but the story’s always going to be more powerful and the main character more likable when it’s HIM WANTING SOMETHING that drives the story as opposed to the story driving him.

But what really placed this script above so many others was the VARIETY IN STORYTELLING. What this means is that when you write a movie like Taken or Bourne, there’s only one beat being repeated throughout the movie – CHARGE THROUGH OBSTACLES TO CONQUER THE GOAL (“take down the CIA” in Bourne, “find my daughter” in Taken).

That can get tiring if every section is like that. Sometimes what intermediate writers will do to alleviate this is write a slow “sit-down-and-talk” scene. But all that does is momentarily alter the pacing. It doesn’t add VARIETY to the way the story is being told.

Variety in storytelling means creating entire sections that have a different purpose and feel than other sections. When you do this right it’s like magic because it keeps the reader off-balance and unable to tell where the story is going.

For example, early on we have a section where Abner goes off to make money on the railroad. It’s a goal-oriented sequence – get a job to support my family. However, when Abner brings the gold home, that section is entirely different. It has no goal. Instead, Rios builds a sense of fear surrounding the gold – that someone may have followed Abner and is planning to kill the family and take the gold.

So even though we’re sitting in one location for 15 pages, we have something that’s driving our interest – a potential threat from outside. And that fear permeates every scene. More importantly to my point, IT FEELS COMPLETELY DIFFERENT FROM THE RAILROAD SECTION.

So that’s something to keep in mind – that you’re not hitting the same story beat over and over again every sequence. Granted, it’s easier to do this when the timeline is extended, like it is here, but crafty writers can achieve this in time-crunched narratives as well.

The only reservation I have about the script is that the ending gets really dark. The whole movie was such a rush and then we’re hit with this hard-to-take finale. I guess it was inevitable but still tough to swallow. However, if you liked There Will Be Blood and The Shining, you’re going to go fucking go apeshit over this.

What a script!

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[x] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: There’s no need to draw attention to jumps in time (writing down: “6 months later”). Remember that time jumps can kill plot momentum. We’re zipping along and then we see: “1 Year Later.” We feel the wind sucked out of the plot. We’ve got to start building momentum all over again. For that reason, only notate time jumps if it’s necessary for clarity. Otherwise, do what Rios does here and use visual cues to show we’ve jumped forward. For example, we’re on an empty strip of land that Abner’s just purchased for his town, than we cut to an almost completed train station and we just seamlessly keep moving through the story.

Genre: Contained Thriller

Premise: In an apocalyptic future, a teenaged girl raised underground by her robotic mother, begins to question whether everything she’s been taught by Mother is true.

About: This Black List script is written from across the pond. So all you UK writers who think getting your work recognized in Hollywood is impossible, don’t give up! Now Green did work as Colin Farrell’s assistant on Miami Vice, but before you go thinking that’s what got him this opportunity, note that that movie came out all the way back in 2006. I doubt Green called Farrell up after ten years and said, “Hey, remember how I kept your coffee at exactly 71 degrees for the entire production of Miami Vice? Can you read my script?” and Farrell was like, “Sure, and I’ll give it to Spielberg tomorrow.” And, to be honest, I’m not sure Colin Farrell, with his current stature in Hollywood, would be able to do anything for Green anyway. Since Green’s short stint in P.A.’ing, he’s written and produced a couple of short films, but this is his first known screenplay.

Writer: Michael Lloyd Green

Details: 102 pages

A few people have asked me, “Why do readers like contained thrillers?” And while the first answer is that they’re cheap to make and therefore, with a cool concept, have a shot at getting made. They’re also scripts that don’t require the reader to take notes.

This may seem like a strange detail to someone who doesn’t read a lot. But all readers know that there are easy reads and there are difficult reads, and the difficult ones are when you have to take a ton of notes.

Like, recently, I read a love story that took place during World War 1 in Germany. Every page, I had to stop and write down either a new character’s name or a location I was unfamiliar with or some important detail about the war. Those scripts take a lot more out of you.

This script has three characters. Not only that, but the characters’ names are Mother, Daughter, and Drifter. Talk about a script tailor-made for no notes! And, look, I know it sucks. A reader’s job is to read. He should suck it up and work hard even when a script is difficult.

That’s a wonderful way to look at things if you’re an idealist. But the REALITY of the matter is that readers are overworked writers who would rather be working on their own scripts. So you can write as an idealist or write as a realist. It’s up to you.

Does that mean don’t ever write a complicated story? No. Of course not. Some of the best spec scripts ever – The Truman Show, Seven, The Imitation Game, American Beauty – they require focus and, yes, the occasional note-taking.

But this is what makes the screenwriting medium so interesting. If you’re going to go that route, you need to know how to simplify the things that need to be simple, how to always make things clear, and how to make the read easy amongst all that detail. And that takes practice. And it takes KNOWING that you have to do that in the first place, because you’ve written a half-dozen screenplays before this one and got lots of coverage saying, “I don’t know what’s going on here. There’s too much.” It takes time to find that sweet spot of “enough to give your script depth” but not so much that it’s hard to keep up.

So with all that swimming in your noon-day noggin, let’s jump into today’s script, “Mother.”

“Mother” takes place in an underground cavern built to sustain people after a nuclear war. The problem is, there are no people. At least not yet. The entity who runs this facility, a robotic entity known as “Mother,” incubates the first human embryo for a plan, we presume, that will open the door up for earth’s repopulation.

Soon, Daughter is born. Daughter loves her robotic mother at first, but when she grows into her teens, she becomes bored and curious. What’s outside of these dark walls? Mother insists that to go outside means death. The air is contaminated and no human beings have survived.

Except that soon after Daughter finds a secret exit, a bloodied woman appears on the other side. Daughter lets her in, and the woman, “Drifter,” begins to spin a tale that sounds a lot different than the one Daughter’s been told. For starters, there are obviously other human beings alive.

Mother finds out about Drifter, and to both Daughter’s and Drifter’s surprise, decides to help her. But Drifter remains skeptical of Mother, and starts filling Daughter in on what she knows of the outside. For starters, there are machines roaming around, killing people. Could Mother be associated with these machines?

Then again, Daughter repeatedly catches Drifter lying about things herself, leaving her to make the impossible choice. Believe the woman who’s raised her, or the woman who represents everything she’s wanted – to be free and live out in the wild? It’s a decision that, most certainly, will end in death… for one of them.

We’ve been here before, right?

Two people in a contained room. A third enters. Wreaks havoc.

We just saw it with Cloverfield Lane.

It’s a recipe that works.

So what has today’s script added to the setup? Well, we’re in the future. We’ve got a robot. That’s different. And we’ve also got a unique relationship. This isn’t two people who’ve been forced down into a shelter against their will. These “people” have been here for awhile. And the fact that they’re family creates the potential for new plotlines.

The first of those is trust – the trust between a mother and her daughter, and how we’re innately supposed to go along with the way our parents raise us. As children, we don’t know any better. So if our father or mother tells us that killing is good, we believe them. Because what else do we have to go on?

That’s the dilemma at the heart of “Mother.” When does raising a child turn into manipulating a child? And aren’t we all, to a degree, manipulated? We’ve been raised on the morals and ethics of the parents who birthed us. And since our childhood years are the most influential on our make-up, we usually take those beliefs all the way through life.

So that’s the undercurrent of Mother, which is interesting, I guess.

But what about the plot? Does Green solve the biggest issue facing Contained Thriller writers: Coming up with enough story to last an entire movie? Unfortunately not. He does okay. But I felt like I read half-a-dozen scenes of Drifter in the Infirmary complaining about Mother and trying to get Daughter to come with her.

Also, Drifter falls short as a character because she’s so mysterious. Again, when you have a character built on mystery, you can’t explore them below the surface. To do so would be to reveal who they are, which is something the character’s not created for. So Drifter ends up coming off as a repetitive sock puppet – there to repeatedly say, “Mother is lying. I’m not.”

Luckily, the Mother-Daughter relationship is compelling enough to overshadow this weakness. Whenever you can write a character who fills two different extremes, you’re going to get some interesting results. (spoiler) That’s what Mother is. She genuinely loves her child, but she’s also perfectly capable of killing her if she isn’t up to speed with what the repopulation of the human race requires.

So “Mother” was an okay execution of a popular setup that did some nice things. But in the end, it didn’t do enough to excite me or advance the genre. In that sense, it wasn’t for me.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: When you’re choosing a script to write, ask yourself, “Is this a note-taking script or a non-note-taking script?” If it’s the former, realize that you’ll be fighting an uphill battle against a reader who will resist the amount of focus required to understand your story. However, if you work hard to make all that extra information clear, and you’ve written an engaging story on top of that, you can travel down this path and survive.

Genre: Sci-fi/Fantasy

Premise: A ragtag group of rebels attempt to steal the plans to the biggest weapon in the galaxy.

About: Rogue One is the first movie in the “standalone” Star Wars universe. Its production struggles have been well-documented, as over 40% of the film was reshot. Look no further than the first trailer for Rogue One to see how bad it got. Barely anything we see in that first trailer is in the final film. The film was directed by Godzilla director Gareth Edwards and comes out… TODAY!

Writers: Chris Weitz and Tony Gilroy (story by John Knoll and Gar Whitta) (based on characters by George Lucas)

Details: 2 hours and 13 minutes

I’ll get right to it.

I was so disappointed by Rogue One that I considered not writing this review.

I thought this movie would at least be decent. Most of the people I trust online liked it. But everyone seems to be wearing their Star Wars goggles (Star Wars Goggles is a phenomenon by which you love a Star Wars movie right after you see it, then several months later realize you hate it).

I’m struggling, ten hours later, to find anything that I liked.

Everything about this film was either bad or weird. And the only times it felt anything like a Star Wars movie was when it cross-referenced the other films.

THERE WILL BE SPOILERS BELOW!!!

For those who don’t know anything about the plot, the infamous Death Star’s killer planet ray was created by a dude who hated what he was doing so much, he built a secret flaw in the system that would allow anyone who knew about it to blow the whole thing up. The Rebel Alliance recruits the man’s daughter, now a criminal, to find her father and retrieve those plans. She, in turn, teams up with a rag-tag group of nasty dudes to go perform the mission.

It’s a pretty good plot, to be honest. So where does it go wrong?

The characters. Oh my God, the characters.

Jyn Erso – Easily the least charismatic lead character in any Star Wars movie. And that’s hard to pull off when you’re competing against the prequels. Holy shit was this character boring. She just looked angry a lot of the time. We don’t need to look further to know why this movie failed. If your lead character isn’t interesting. If we don’t care whether they succeed or not, the most adept screenwriting plotter in the world can’t save the film. I felt 1000 times more emotional watching William Wallace (an obvious inspiration) lose his father as a kid than I did Jyn Erso cradling her dead father. And I’d known William Wallace’s character for one scene. Boring boring boring boring. People can hate on Rey. But one thing Rey was not was boring.

Cassian Andor – So we’ve at least gotten the worst character out of the way, right. Nope! There’s a character who’s, somehow, even more boring! Cassian Andor! I think this guy was supposed to be the Han Solo of the group, but here’s the problem. He had no wit and no charm. Like most characters in this movie, he kept his thoughts close to the vest which meant we never got a chance to know or care about him. This is the problem when everyone has a secret motive, is we don’t get to know them as people. And if we don’t know them, we don’t care about them.

Bodhi Rook – Okay, phew. We’re done with the scathing character assassinations, right? I mean, it can’t get worse than that. Oh no, it can get worse. It can get so very worse. I am officially announcing Bodhi Rook as the second most annoying character in the Star Wars universe behind Jar Jar Binks. WHAT THE FUCK WAS GOING ON WITH THIS CHARACTER? Half the time he was mumbling to himself. The other half he had to be told to do something eight times before he understood it. Riz Ahmed better thank his lucky stars that The Night Of came out this year. Or there’s a good chance this role would’ve ended his career.

So did I like anyone? Yeah, Ben Mendelsohn was solid as Orson Krennic. Donnie Yen was cool as a blind dude with Jedi aspirations. And K-2SO was good with a few funny lines. But it was like using the Chicago Fire to roast marshmallows. Are these performances really that tasty when the rest of the movie is burning down all around you?

And don’t get me started on the special effects. There hasn’t been a moment I’ve felt more uncomfortable during a movie all year than when General Tarkin’s CGI character appeared. He looked and moved so robotically, it was like I was transferred back to 2002 CGI. This is Star Wars. There isn’t a production that has better resources in the special effects department. Hell, Star Wars CREATED the special effects industry. And this is what they give us??? Some video game CGI character that takes us right out of every scene he’s in?

Then there’s Vader.

No.

Just no.

Everything about Vader in this movie sucked. Meeting Vader on his nerdy Lava Hideout (an early iteration of Vader’s home that previous Star Wars teams scrapped because it was so dorky) for a scene that made no sense other than to… well, have a Vader scene. And then, to resort to giving Vader a 1980s Arnold Scwartzennegar zinger???? “Make sure not to choke on your aspirations?” It was cringe-worthy to the millionth degree. I felt like I was watching two 12 year old’s rendition of what a new Darth Vader scene should look like.

And then in the end, we get this Vader song and dance kill a bunch of people in a hallway scene that WAS THE MOST UNNECESSARY SCENE IN THE MOVIE. Not only does it show that the writers don’t understand why Vader is cool (Vader is cool cause he’s stoic), but think about this for a second. If you’re a kid who’s never seen a Star Wars movie, and you’re watching this film, you’d be like, “Why is that guy in the dark suit who was in one pointless scene all of a sudden the star of this ending?”

Then there was the score.

What the hell did this new guy do to the Star Wars score???? He turned it into one of those scores you hear in Star Wars parody videos where it’s clear they didn’t get the rights to the music. So they changed up the second half of the chords to stay out of legal trouble. That’s what Micahel Guggianico’s entire score felt like. You kept waiting for the iconic melody and it never came. It was like bad sex. Never any climax.

And I don’t usually talk about score cause I don’t know shit about it. But there is no franchise more tied to its score than Star Wars. Maybe after a second viewing I could appreciate it more. A lot of good music tends to grow on you. But honestly? I don’t know if I’m going to watch this again. And you’re talking to someone who’s watched every Star Wars movie at least five times (even the prequels!).

Is there anything, ANYTHING, that I liked here? Let’s see. I thought Jedha was a cool idea. That was one of the better sequences. And I thought the tropical island location was a fresh way to explore a Star Wars battle.

But you know what bothered me? This plot was BEGGING our characters to sneak onto the Death Star, yet they never go there! Think about it. The original Star Wars was limited in its ability to explore the Death Star due to budget. This movie could’ve explored the intricacies of the Death Star on a whole new level. The most iconic villain lair of them all. Yet we never go there. It was an odd choice to say the least.

Rogue One helped me better understand why Star Wars worked. Star Wars was a simple story about a boy with big dreams. It’s so relatable. All this shit about “STAR WARS MUST BE DARK” is a big part of why this movie failed. All the characters were rebels and resistors. There was no purity, no one truly good to get behind.

It resulted in a beautiful to look at film with no soul.

[ ] What the hell did I just watch?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the price of admission

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: If your main character is boring, you’re fucked. Plain and simple. And let’s go further than that. If the bulk of your main character’s personality is introverted, it’s hard for that character to stand out. You can only have a character stare out forlorn for so long before we get sick of them.

Michael Jackson once sang, “I’m looking at the man in the mirror. I’m asking him to change his ways.”

I don’t know if mega-star screenwriter Steven Knight (Allied) is a Michael Jackson fan or not, but I was reading an interview he did at Slash-Film the other day, and one of the questions asked of Knight was one that has pockmarked the screenwriting community for centuries. It’s the closest thing we have to a trigger question. Our equivalent of a political nut walking into a room and saying, “I can’t wait for Trump to build that wall.”

“SHOULD YOU FOLLOW THE RULES?”

Early in the interview Knight says that he avoids following screenwriting rules, specifically the one that states a character has to CHANGE over the course of a movie. When then asked which rules he isn’t fond of, Knight doubled-down on character change…

I mean, the arc thing is interesting. It’s good sometimes to have a character that starts as one thing and ends as another, but James Bond, Hercules, these are pretty enduring stories. [Laughs] Like a Greek myth. In a Greek myth, you can have the characters and objects, and it just goes through these events in the same as a computer game now.

I’ve always found this discussion fascinating because I believe it’s essential that a character change over the course of a movie. In fact, I’d argue that 99% of main characters in films do change, and that if your character doesn’t change in some way, we’ll feel let down, even leave disliking that character.

The only time a character doesn’t change and it still works is when that character dies because of their inability to change. I just watched Hell or High Water, and in that movie, the trouble-making brother lived a selfish sinful life. He never changed his ways (spoiler) and he ended up dying because of it. We also saw this with Robert DeNiro’s character in Heat.

Here’s where everyone gets tripped up though. They think that “change” has to happen along the traditional lines of assigning your character a flaw, and then having that character overcome that flaw by the end of the movie.

I agree that, when done well, this is the most effective way for change to work. When a selfish character (Trainwreck) learns to become selfless, we feel warm inside. When a stubborn character (Hoosiers) learns to listen to others, we feel tender inside.

However, the more scripts I read, the more I realize this type of change doesn’t happen often. And a look into history tells us why. The time when this advice became popularized was in the 80s and 90s, a period when comedies, rom-coms, and less serious fare dominated. In those movies, the “flaw-change” worked perfectly. The films (along with animated and sports movies), were already skirting reality, so the fact that this unrealistic 180 degree character turnaround occurs at the end of the movie didn’t faze anyone. They bought into it wholeheartedly.

But when you watch a movie like Drive or Bourne or Mad Max or Arrival – you don’t see traditional flaws explored. And because you don’t, you don’t see that arc Knight is referring to.

BUT…

Those characters still change. And the reason screenwriters miss it is because they’re looking specifically for the flaw-change. But alas, my screenwriting snickerdoodles, there are OTHER WAYS TO CHANGE A CHARACTER.

Two big ones, in fact:

LEARNING

and

OVERCOMING

Learning is just like it sounds. The character doesn’t have to become a different person by the end of the movie, which is where rule-defamers get their panties in a bunch. But they do need to learn something. I consider this a “mini-change,” and while not as earth-shattering as a core change, it still leaves the audience feeling good, since the character has evolved.

One of my favorite movies of all time is Ferris Bueller’s Day Off, a film used by flaw-change naysayers as proof that your main character doesn’t have to change over the course of the film. Ferris Bueller has no flaw, they say. And therefore he doesn’t fix his flaw by the end of the movie.

But let’s look at that analysis more closely. Is Ferris Bueller the same person at the end of that film as he was at the beginning? I’d say no way. Ferris has LEARNED two valuable lessons – the value of friendship (with Cameron) and the value of family (with his sister). If Ferris hadn’t changed, he’d still be joking around when Cameron has a breakdown destroying his father’s car. If Ferris hadn’t changed, he wouldn’t have connected with his troublemaker sister, who saves his ass at the end of the day.

The operative word here is that Ferris has LEARNED something. And if you’re not going to add a full-scale flaw-change, this is a nice secondary option. Make sure your character has learned something by the end of the day. It doesn’t have to be big. But it should make us feel that, going forward, the character is better equipped for life.

Next we have “OVERCOMING,” and overcoming comes in two flavors:

LOSS

ADDICTION

Movies that tackle these subject matters tend to be more serious. As a result, the gimmicky “overcoming a flaw” stuff doesn’t work as well (it can work, but it takes more skill to do so). The good news is, this is a fairly easy “change” to pull off. Since the problem is built right into the character, all you have to do is have the character overcome that problem and they have “changed.”

Arrival is an example of “overcoming loss.” Amy Adams’s character, Louise, has lost her child. Her entire life is defined by this loss. By the end of the movie, she’s able to find peace with the loss and move on. Louise is in a better place at the end of the movie than she was at the beginning (note: I know it’s more complicated than that because of the time stuff – but I don’t want to get into spoilers here).

I want you to think about that for a second because it gets to the heart of why, I believe, Steven Knight is wrong. If Louise is the same bummed out hopeless person in the last frame of the movie as she was at the beginning, would we be satisfied? I’m willing to bet you’d all have the same reaction: “Well what the fuck was the point of that then?” This is why change is important. It makes us feel like the journey we just went on had a point.

For an example of a character overcoming addiction, look no further than The Girl On The Train. That film is about a woman whose drinking is so bad, it’s preventing her from solving a murder. If she doesn’t change her ways (her drinking), she will wallow in this drifting pointless existence til the day she dies. Change is imperative for her to succeed and for us to feel satisfied. And she does just that.

And that’s what I want to get across here. Characters must change over the course of the story. It doesn’t have to be with a flaw. It can be by learning something. Or it can be by overcoming something within. But they can’t be at the exact same point at the end as they were at the beginning, or else what’s the point of making us watch your stupid movie for two hours?

I’m so sure of this, that I pose a challenge to you: Name me any good movie where the main character doesn’t change in the three ways listed above (flaw, learn, overcome) where the character doesn’t then end up dead.

And yes, I know the first film you’ll go to is the James Bond series. I don’t know these films well enough to argue against them. But I have a feeling that, in a lot of Bond films, Bond learns something by the end of the movie. Especially in the Daniel Craig versions, which are more character-driven. But what I’m really curious about is if anyone can give me examples other than Bond. And remember, the films have to actually be good! Meaning, the act of not changing the characters resulted in a strong film.

Go at it!