Search Results for: the wall

Congrats to Scott Serrandell who won this past weekend’s dialogue mini-contest. Some really funny dialogue, exactly what I was I was looking for. I’ll be looking forward to see what he does in the official Scriptshadow Short Script Contest.

Genre: Drama

Premise: (from The Black List) A multigenerational love story that weaves together a number of characters whose lives intersect over the course of decades from the streets of New York to the Spanish countryside and back.

About: Dan Fogelman broke onto the scene with the original Ryan Gosling and Emma Stone pairing, “Crazy, Stupid, Love.” His next project, the oldies-Hangover film, Last Vegas (which he made clear to me was written BEFORE The Hangover), was a sneaky hit. Mixed in there were The Guilt Trip and Danny Collins, neither of which did well. Nowadays, Fogelman has moved over to television, with his viral NBC show, This is Us. “Life Itself,” a highly ranked 2016 Black List script, is his return to features and will star Oscar Isaac and Olivia Wilde. Fogelman will direct.

Writer: Dan Fogelman

Details: 116 pages

Dan Fogelman is one of the biggest screenwriting success stories of the past decade. He came out of nowhere five years ago to sell three huge specs at a time when everyone thought the giant spec sale was dead. And he was doing it with the kinds of movies Hollywood doesn’t make anymore, mid-budget light-as-a-feather dramadies with heart.

Things looked bad when one of his biggest sales, Danny Collins, however, failed badly at the box office. It was looking like Fogelman was in trouble. So he just hopped over to the TV side where he now has one of the most buzzed about shows on television (This Is Us). When you think about it, Fogelman’s character-first stories were always better for television anyway. So we probably should’ve seen it coming.

But now Fogelman’s back with a feature. Let’s see how he did.

I have to admit, the last thing I expected when I opened a Dan Fogelman script was Samuel Jackson screaming at me. Yes, Samuel Jackson is our narrator. At least for now. There’s a lot of “at least for now” in Life Itself. To give you a taste of that, we meet Julianne Moore a few pages later. And Julianne Moore gets slammed into by a bus, her bones and guts sprayed everywhere.

Yes, Life Itself is Dan Fogelman unhinged.

Confused yet? I was. Eventually, after things settle down, we meet Will Dempsey, a sometimes-writer who’s devastated by his pregnant wife, Abby, leaving him. Will was so destroyed, in fact, that he spent six months in a nut house. Now he spends most of his days talking to his therapist, who looks a lot like Julianne Moore.

We jump back in time to see how these two met. You’ve never seen two people more perfect for each other and more in love than these two. Which begs the question – how could Abby possibly leave Will?

To answer that question, we’ll need to get into spoilers, as Life Itself is one giant spoiler-fest. Which makes sense since life itself is a spoiler fest. So don’t read on if you don’t want to know what happens. I’ll be semi-vague in order to protect the script’s twists. But what we learn is that Abby and Will didn’t divorce. A far worse tragedy occurred. And that is why Will has gone off the rails.

Oh, but if you think that’s all you’re getting here, let me remind you that Life Itself is DAN FOGELMAN UNHINGED. After getting over the shock of the earlier tragedy, Fogelman hits us with a DOUBLE TRAGEDY that was so shocking, I spent the next ten pages reading the script through tears. No, I’m not kidding.

Without getting into too much detail, we cut to years later where we follow Will and Abby’s daughter, Dylan (named after Abby’s favorite musician, Bob Dylan), growing up, and explore how the tragedies of her earlier life have turned her into the rebellious and dangerous beauty she is today.

In the meantime, we follow a poor Spanish family who is peripherally attached to Abby and Will. And, at a certain point, we realize that that Spanish families’ story is going to loop back around and re-intersect with that of our original characters. But while we’re praying it intersects the way we hope it will, there are no promises when it comes to Fogelman’s most twisty and turny narrative yet.

I apologize that summary was so vague but there are too many major twists and turns and I don’t want to ruin them ahead of the film. That makes this script difficult to analyze but I’ll do my best.

I want to start with bravery. As a writer, one of your jobs is to evolve. Each script you write, you want to push yourself into new, even uncomfortable, territory. If all you’re doing is rehashing the same old characters and storylines that you always do, you’re never going to write anything great.

I did not recognize this Dan Fogelman at all. I remembered in his previous scripts that he always played things safe and predictably. He did safe and predictable well. But you always knew what you were getting from Fogelman, and that kept his scripts from ever elevating into awesomeness.

Life Itself is a whole other beast. At first, Sam Jackson is breaking the fourth wall, screaming at both us and our hero. Then Julianne Moore gets violently slaughtered by a bus. Then we’re hit with two major fucking traumatic twists within a ten page period. Then, for the second half of the script, we’re meeting this whole other family in Spain…

It’s like, “What the hell??”

Truth be told, this story is better suited for a novel or a television show. Whenever you have multiple characters and you really want to delve into those characters (I mean, beyond the basic likable trait and character flaw), you need time. And you can only get that with the 60,000+ words a novel affords you or the 7+ seasons a TV show does.

When you try to do the same thing with a feature, you always run up against the problem of plot. Features need the plot to keep moving. And that always conflicts with character development. Yes, you can do both. And the best writers do. But only to an extent. I don’t care how talented you are. If you need your characters to destroy the Death Star by the end of the movie, you need to keep your plot moving along. And that takes away those slower character-driven scenes that are such a staple in TV shows.

And yet, Fogelman gets as close to pulling it off as one can. I’m not sure how he does it but I want to say the twists are a big part. He knows that because there’s no plot, if he hits you with 40 scenes in a row of characters saying I love you and I hate you, we’ll be bored to death. So he slams you with these huge shockers that we never saw coming and it’s like this jolt of espresso that powers us through another 15 pages of character development until the next twist arrives.

I do think this approach finally bit him in the ass, though. Because the first act was so strong and so unexpected, the second quieter half, with the Spanish family, couldn’t quite live up to it. And while there will always be parts of a screenplay that play better than others, you should try to make it so that each quarter of your script is better than the previous quarter. That’s because you want your final quarter to bring the house down. And in Life Itself, it’s the first and second quarters that bring the house down.

Still, this is quite an achievement. It’s unlike anything you’ll read all year. It’s complex yet a surprisingly quick read (one of Fogelman’s specialities). I would go so far as to say this is his best script. Could it have been better had he hit a home run in the 3rd Act? Sure. But I’d still recommend this to anyone wanting to learn how to write vibrant memorable characters.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[x] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: As much as I hate flashbacks, there’s no question that they help the reader care about a character more. For example, if I introduced you to John, the hockey player with an attitude, all you see is a hockey player with an attitude. But if, at some point, I flash back to when John was a child and showed that he witnessed his father beat his mother to death, that character is fleshed out ten-fold. He carries so much more weight. That’s what Fogelman does here on multiple occasions and it really helps his characters shine.

I’m not going to lie. I wasn’t thrilled with the results from last week’s dialogue challenge. Nobody blew me away with any world-changing dialogue. It seemed like some people weren’t even paying attention to the dialogue. They had an idea for a short and dialogue happened to be a part of it. I take responsibility for this. Obviously, something I’m saying isn’t getting through.

So I want a do-over. I think you guys are capable of much better. And we’re going to be learning from the master today so I’m hoping that’ll inspire you. But before we start, there was one issue from last week I want to eliminate immediately…

TOO MUCH DESCRIPTION

When dialogue is being featured, you don’t want anything mucking it up. And nothing mucks up dialogue faster than a bunch of description. You want the reader’s eyes on the center of the page. You don’t want them to keep looking left to read some superfluous action. It KILLS the rhythm of the scene. And rhythm is one of the keys to great dialogue. So please: KEEP DESCRIPTION TO A MINIMUM WHEN FEATURING DIALOGUE.

Now, on to today’s three dialogue tips, inspired by Quentin Tarantino.

IRONY

Like most things in screenwriting, dialogue improves with irony. You achieve this by having your characters speak in a manner that’s the opposite of who they are. A famous example of this is Jules and Vincent in Tarantino’s Pulp Fiction. They’re the chatty hitmen. They’re talking about burgers, footrubs, TV pilots. Hitmen aren’t supposed to be fun and chatty. So it’s ironic. And audiences eat irony up. Nuns talking about fucking. Clowns talking about suicide. Kids talking about 401ks. Use irony to write better dialogue.

LOOMING SENSE OF DREAD (SUSPENSE)

Set up a scenario by which something bad (or potentially bad) is coming, draw the resolution out as long as possible, and have fun with the dialogue in the meantime. The space between the beginning and end of a line of suspense is one of the easiest places to write dialogue because your audience is so dialed in. This allows you to have fun with your dialogue as well as the particular conflict within that scene. The best example of this in Tarantino’s world is the beginning of Inglorious Basterds. Hans the Nazi comes into a farm house looking for Jews (who happen to be hiding underneath the floor). Tarantino has so much fun as we wonder if Hans is going to find what he’s looking for. Also note that Hans is a chatty polite Nazi (irony!).

SEXUAL TENSION WITH AN OBSTACLE IN THE WAY

An easy way to bump up your dialogue is to put two characters with heavy sexual chemistry together, then place an obstacle in the way of them being able to act on that attraction. The bigger the obstacle, the better the dialogue will play out. Tarantino’s most famous scene ever is built around this conceit: Vincent Vega and Mia Wallace going out for dinner. Vincent is doing this as a favor to his boss, who’s married to Mia. So the obstacle between them is as big as it gets. If Vincent does anything with Mia, he will be killed (as Tarantino cleverly set up in the earlier scene between Vincent and Jules). This is why the sexual chemistry (and subsequent dialogue) crackles so much. Because they fucking want each other but cannot talk about or act on it. This creates subtext, which adds a whole other layer underneath the already fun dialogue that’s happening on the surface. An easy way to write great dialogue.

BONUS TIP: DIALOGUE OBSTACLES

I’ve already told you guys to place obstacles in front of your hero’s goal. So if Daniel is trying to defeat Johnny in the karate tournament, you give him a broken leg (obstacle) to make achieving his goal even harder. What I’ve noticed about Tarantino is he places obstacles in his dialogue. So it’s rarely as simple as, “Are you okay today?” “Yeah, how bout you?” “Tough day at work.” “Hey, one day at a time, right?” Instead, when someone says something, he’ll have the other character challenge it, or say he doesn’t know what he’s talking about. This is the “obstacle” that forces the first character to re-route or explain things further. What this does is it gives the dialogue more of an unpredictable pattern, and adds a playfullness to it. Here’s an example:

Notice how he says, “I don’t watch TV.” That dialogue obstacle leads to the best line in the exchange, “Yes, but you’re aware that there’s an invention called televsion, and on that invention they show shows?” That line is nowhere to be found without a dialogue obstacle.

And there you have it. If you look at Tarantino’s less memorable scenes, they’re usually scenes that aren’t utilizing these tips. For example, the Butch and Fabienne motel room scene in Pulp Fiction talking about pancakes has some fun exchanges, but it’s way slower than a typical Tarantino scene because it isn’t using any of these devices.

So tomorrow, that’s what this weekend’s short contest will require. You’ll have to use two of these four devices. And also, remember to have fun with your dialogue. Stay away from the mundane and the obvious. Memorable dialogue requires characters to say things in colorful, unexpected, and unpredictable ways. I didn’t see enough of that last week. Hopefully, that will change tomorrow!

AND DON’T FORGET TO SIGN UP FOR THE OFFICIAL SCRIPTSHADOW SHORT SCRIPT CONTEST! IT’S FREE AND THE WINNER GETS THEIR SHORT PRODUCED!!!

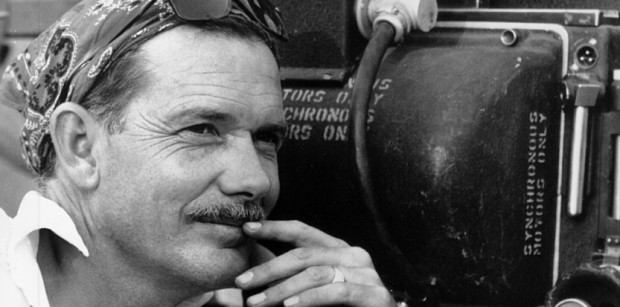

Genre: True Story

Premise: (from Black List) After losing his luster and respect in Hollywood, famed director Sam Peckinpah hopes to direct his next great film with financial backing from Colombian drug lords and brings along a novice screenwriter to write the film in Colombia.

About: “If They Move Kill’em” landed on the 2012 Black List and was Kel Symons breakthrough screenplay. For those who don’t know, the subject of the script, Sam Peckinpah, was one of the best directors of the late 60s and early 70s, responsible for such classics as The Wild Bunch, The Getaway, and Straw Dogs. He was also a notorious addict who burned the candle at both ends AND in the middle.

Writer: Kel Symons

Details: 96 pages – 1st draft

Sam Peckinpah was the anti-establishment writer-director of his time. He hated… well, pretty much everything besides making movies. And to be involved in one of his films was like riding on a rollercoaster built entirely out of razor blades. While it may not have been enjoyable to be a part of the Sam Peckinpah legacy, you sure as hell came away with a lot of stories.

“If They Move Kill’em” is constructed around this conceit. It’s 1978, which was long after the apex of Peckinpah’s career. The Wild Bunch, his most famous film, was a decade old at this point. And while previous studio regimes had a “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” approach to substance abuse, movies were becoming big business, and that meant more scrutiny at every level. Heck, Star Wars had just come out a year earlier. Everyone was starting to see what movies could become. Which made Peckinpah a relic of the old guard.

This is perhaps why Peckinpah decided to make his next movie in Columbia using 100% drug money. Peckinpah’s drug-fueled logic was this: Sure, I might be using blood-soaked hundred dollar bills to make entertainment, but at least I don’t have to answer to a bunch of self-serving liars in suits hell-bent on destroying my vision. The Columbians loved his Westerns. They’d let him do whatever he wanted.

There was only one problem. Peckinpah wasn’t making a Western. He was a making a commentary about the Columbian drug-trade, something he didn’t necessarily mention when all of the “financing” was being put in place. Therefore, when he flies down to Columbia to finalize the details, his drug-lord handlers are none too thrilled about this surprising turn of events.

Meanwhile, Peckinpah has hired a neophyte screenwriter, Charlie Stetler, to write his film. Charlie, a straight arrow with an 8 months pregnant wife, isn’t prepared for the world he’s dropped into. This is a man whose most exciting daily event is when the coffee machine breaks at the community college he teaches at. Now he’s walking through metal detectors with suitcases full of half-a-million dollars.

Peckinpah uses a steady diet of gin and tonics, whiskey, and Columbian coke to fuel the prep for his film. But when the Madero brothers, his financiers, learn that Peckinpah isn’t giving them the next Wild Bunch, they go apeshit and consider killing off the prick and his sidecar screenwriting act.

What scares the shit out of Charlie is that Peckinpah isn’t worried about this one bit! He’d rather challenge random drug lords to arm-wrestling matches than figure out a way to escape back to America before they get a bullet to the head. That’s when Charlie considers the unthinkable. Maybe this was all part of the plan. Maybe Peckinpah came down here to end his life in one final blaze of glory. And poor Charlie is just collateral damage.

Boy, this started out great. Peckinpah is one hell of a character. He is a feeding frenzy of drugs, alcohol, and women. He is a raging lunatic, a hurricane looking to sweep anything within a one mile radius into his circle of pain and loathing. And for that reason, whenever we’re highlighting Sam, the script works.

Where “If They Move Kill’em” runs into problems is in its plotting, as it never seems like Symons has much of a plan here. It’s almost like he’s hoping once we land in Columbia, the movie will write itself. In his defense, it would seem that way. He’s got this great character in this volatile setting. Why wouldn’t the script write itself?

Welcome to screenwriting. Where IT’S NEVER FUCKING EASY. Even when you think it’s going to be easy, it’s not easy. I can’t tell you how many times I’ve thought to myself, “Well, at least I have that one scene coming up. That scene is going to be amazing.” Then I get there and realize it’s the hardest scene in the script to write.

What “Shoot’em” reminded me of is that you still have to outline. You still have to plot. You still have to structure. Because if you don’t, your story just sort of drifts. It may drift into some interesting places. But it’s still drifting. The reason you plot is so your story can build – so that it moves towards an identifiable climax, something we can look forward to.

That’s the problem here. Where are we moving towards? Are we moving towards an agreement to make the movie? Is that the main character’s goal? We’re certainly not moving towards the completion of production, since 3/4 of the way into the script, we’re nowhere near shooting a frame of film. So the audience is asking, “What’s the end game here?”

How this hurts you is simple. You don’t know where you’re going so you just start writing shit down hoping for the best. About 70 pages in, for example, Sam and Charlie are sent off to a cocaine processing plant while the Madero brothers figure out what to do with them. And then we just watch our characters hang out.

You’re 3/4 of the way into your movie. Your characters shouldn’t just be “hanging out.” With 30 pages left in your script, we need to be building towards something. Especially when you’ve made a promise to the audience by chronicling this insane main character.

A great example of doing this the right way is The Wolf of Wall Street. That film has a clear structure. We see the rise of Jordan Belforte. Then we see the fall. We always know where we are. And, more importantly, we’re always MOVING. We’re never just sitting around waiting for things to happen. That’s the death knell of any screenplay. If your characters are waiting for anything for longer than a scene? You need to rewrite that section of the script.

Yet I wouldn’t give up on this project. Peckinpah is a person who’s worthy of being written about. He’s built for biopicing. I could see every actor between 50-60 dying to play him. Bryan Cranston would probably be the way to go. Maybe even Pitt. But this script is a reminder that a character isn’t enough. It’s a superb starting place. But you still need a plot with a plan. And I never saw that here.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: The “innocent” thrown into the lion’s den is a great trope. Shonda Rhimes has built an entire TV empire around this setup. Remember that you’re always looking for conflict and contrast in storytelling. If someone’s in an environment they’re familiar with and/or comfortable in, that’s boring. But throw them into a world that they despise or are scared of, now you’ve got a movie. Peckinpah going to Columbia wouldn’t have been enough. He’s just as crazy as his hosts. But Charlie, the sweet and innocent screenwriter with a heart of gold being thrown into Columbia? Now you’ve got a movie. To test this, write a scene where a scheming drug addict walks into a strip club. I guarantee it will suck. Now write a scene where a bible salesman is dragged into a strip club. Watch the scene come alive.

Last month I was reading a script that wasn’t very good and I asked myself, what could make this script better? The answer to that question sounded something like this: more original characters, more active characters, characters with more depth, less on-the-nose dialogue, higher stakes, more unique choices, a better handle on structure, a second act that doesn’t repeat itself, more obstacles to overcome, a flashier villain… and the list goes on.

The point being, this writer needed to spend more time learning the craft.

So then I thought, well that’s kinda lame. I mean, yeah, they do need to learn this stuff. But what if there were some things they could do RIGHT NOW that could leave a big impact on their script.

That’s what gave me the idea for today’s article. There’s lots of screenwriting tips out there, lots of lessons, lots of tools. But what tools give you the BIGGEST BANG FOR YOUR BUCK? That means you don’t have to do a lot, and yet you get tons of upside through the application.

So after you read this, bust open that script you’re working on and incorporate a few of these immediately. And because I enjoy a flair for the dramatic, I’ll be listing our Bang For Your Buck tools in reverse order, with the best tip coming last. Here we go!

NUMBER 5: TICKING TIME BOMB (OR “TICKING CLOCK”)

I just completed a consultation script the other day that had way too slow of a second act. Months were going by with no end in sight. I was getting bored. And I thought, if only there was a ticking time bomb here, the story would feel so much faster.

A ticking time bomb is any looming moment that spells doom. And here’s something a lot of Scriptshadow readers don’t know. A ticking time bomb is not limited to the entire narrative. It can be used for single acts, single sequences, even individual scenes. If you’ve got a boring talky scene between two characters, add a ticking time bomb!

Let’s say you’re writing a teen comedy like The Edge of Seventeen and you have a conversation between your leads in one of their bedrooms that’s boring no matter how you arrange the dialogue. Pull the scene out and place it outside of school, five minutes before the first bell rings. Give the talk some importance (it’s a conversation that needs to be had), and make it so if the hero gets in after that bell, he gets detention all weekend. Watch that very same conversation come alive. Ticking time bombs give you so much for so little when you know how to use them.

NUMBER 4: UNDERDOG

Granted this is something you’ll probably have to do at an earlier stage in the writing, but underdog characters are so beloved by audiences that using them is almost like cheating. You barely have to do anything and the audience is rooting for your hero.

If you look at the 10 highest grossing movies of 2016, 7 of them are led by underdog characters (Rogue One, Finding Dory, The Secret Life of Pets, The Jungle Book, Zootopia, Suicide Squad, Sing). Not every story is right for underdogs (Batman vs. Superman), but it sure helps when they are.

NUMBER 3: SHOW DON’T TELL

Welcome to one of the most common mistakes beginner AND intermediate screenwriters make, and one of the easiest ways to identify a newbie. If a writer’s characters are always solving problems with what they say, rather than what they do, I know the script is in trouble.

But here’s the great thing about “show don’t tell.” It isn’t just about looking less newbie-ish. It actually MAKES YOUR SCRIPT BETTER. Even a lazy use of showing tends to outclass an inspired use of telling. It’s why one of the first tasks they have you do in film school is shoot a movie without sound.

I was watching the pilot for the British TV show, Utopia, last weekend. In the first scene, these thugs enter a comic book shop, and one by one, kill everyone in it. Then, just as they’re about to leave, one of the thugs bends down, and we see that a young boy is hiding under one of the stands.

We could’ve easily turned this into a dialogue scene. “What are you doing under there, little guy?” “Nothing.” “What comic is that you’ve got?” “X-Men.” “Yeah? You like X-Men?” And blah blah blah. But no, they don’t do that. The thug, who’s been working his way through a box of candy the whole scene, extends the box of candy out to the boy, a psychotic look on his face. And the last shot is of the boy reaching forward to take a piece. Then we cut out. It’s a much better scene because of the showing.

NUMBER 2: DRAMATIC IRONY

Ooh, this is a good one. Dramatic irony is the act of letting the audience know something the hero (or the key character in the scene) does not know, and typically that something is bad.

So let’s say a surgeon is doing a routine appendix surgery on a patient and the patient unexpectedly dies. We then cut to the patient’s wife, who’s casually reading a magazine in the waiting room. We stay on the surgeon, as he gulps, and slowly moves towards the wife to tell her the bad news.

This is dramatic irony. We know the wife’s husband is dead before the wife does. This lets us play with the reveal, as the surgeon comes up and asks to speak with the wife. And the wife launches into an opinion about an ad in the magazine she’s reading. And the surgeon is looking for the right moment to butt in. And so on and so forth. And we just play that dramatic irony out.

Dramatic irony ALMOST ALWAYS WORKS. It’s really hard to fuck up if you know what you’re doing. (bonus tip: The more that’s at stake in the scene, the better the dramatic irony will play).

NUMBER ONE BANG FOR YOUR BUCK SCREENWRITING TOOL… SETUPS AND PAYOFFS

Not only are setups and payoffs one of the easiest things to learn, but they’re mind-bogglingly effective. You could introduce the dumbest plot beat ever. But if it’s a payoff to an earlier setup, the audience will gleefully cheer, “Of course! Because of the thing earlier!!!” There’s something about connecting two things on their own that sends audiences into a euphoria.

I divide setups and payoffs into two categories. Power setups and payoffs and Fun setups and payoffs.

Power setups and payoffs work by introducing something seemingly innocuous, not drawing too much attention to it, but just enough attention so that it’s remembered, and then later, have that seemingly innocuous thing be the solution to a key plot point.

One of the best examples of this is when the Crazy Clock Tower Lady in Back to the Future barges in between Marty and his girlfriend right before they’re going to kiss, and screams, “Save The Clock Tower,” before launching into the Clock Tower’s history, which includes it being destroyed when lightning struck it over 30 years ago.

Then, later, when Marty is thrown into the past and he and Doc are trying to find a substitute for nuclear energy and Doc confesses that the only thing in the 1950s that has that same kind of power is a bolt of lightning, but unfortunately there’s no way to tell when and where they’ll strike, Marty holds up the Save the Clock Tower flyer and says, “We do now.”

Fun setups and payoffs don’t affect the plot but never fail to leave a smile on the audiences’ face. Another example from Back to the Future is when, in the present, Marty’s mom throws a sheet cake down welcoming “Uncle Joey” back from jail. “We have to eat this ourselves. Uncle Joey didn’t make bail again.”

Then later, when Marty is in the past and visits his mom’s house, he sees Uncle Joey as a toddler in his playpen. Marty leans down, “Better get used to these bars, kid.”

Back to the Future is actually the best movie to watch to study setups and payoffs. But the point is, by setting something up early and paying it off later, the audience feels like they’ve been a participant in the movie, creating the illusion that they’ve broken through the fourth wall. It makes them feel good. And you barely had to do anything to get them to feel that way.

Genre: Biopic

Premise: Thomas Edison and George Westinghouse battle it out to light the Chicago World’s Fair. The winner will end up lighting America.

About: Graham Moore burst onto the scene when he wrote The Imitation Game, a script that snagged the top spot on the Black List and then went on to surprising box office success. Moore would eventually win the Oscar for best adapted screenplay. The scribe, an admitted history junkie, did double duty this time around. He wrote a book about Edison and Westinghouse, then adapted it himself. The film will reteam Moore with Benedict Cumberbatch, who will play the prickly Thomas Edison, and director Morten Tyldum. The film will also star Eddie Redmayne as the main character in lawyer, Paul Cravath. (edit, oops! I got these two projects mixed up. Cumberbatch is appearing in The Current War. My fault!)

Writer: Graham Moore

Details: 134 pages

While everybody’s worked up about the upcoming Oscars, I’ve already moved on to next year’s Oscars! And today, we have what will surely be a major contender in the top categories.

Moore finds himself in a very enviable position. He’s a screenwriter who loves biopics living in the golden age of biopics. Outside of a couple of names (Aaron Sorkin comes to mind), there isn’t anyone better than him at it. And he’s proven that again, today.

26 year old Paul Cravath was only in law school two short years ago. Now he’s been tasked with telling one of his firm’s biggest clients, George Westinghouse, to give up his bid for lighting Chicago’s World Fair.

It’s 1888, a time when electricity is just starting to make its way into cities. Everyone knows that whoever can win this war will be rich beyond comprehension. The person leading the pack is Thomas Edison, who’s created a functional, if sloppy, light bulb.

George Westinghouse, on the other hand, has created a light bulb with the kind of warm dreamlike glow that leaves you feeling all fuzzy inside. The problem is that Edison came up with his bulb first. And he’s suing Westinghouse on a number of fronts to make sure he can’t light the fair.

Now that doesn’t sound fair, does it?

Westinghouse, against the advice of the firm, employs Paul Cravath to fight Edison tooth and nail. There has to be a flaw in his patent that will allow Westinghouse to win this battle. The problem is that Paul doesn’t have enough manpower to fight someone as big as Edison. There aren’t enough hours in the day.

So Paul invents the first ever hierarchal legal research system, employing associate attorneys who can do the medial work for him so he can focus on the big picture. Ironically, this system is as inventive as the light bulb, as it would become the operating foundation for every working law firm today.

But will that be enough to take out Edison? Only one way to find out.

I always find it interesting where a writer places his point of view. I mean, you have Thomas Edison. You have George Westinghouse. They are the “big picture” characters here. Yet Moore chooses to tell his story from a lawyer’s point of view. Was that a smart move?

Well, the core component of all drama is conflict. Where the conflict lies is where the entertainment is going to be. So Moore asked, where do these two titans meet? They meet at the point of this patent. And wherever there’s a patent battle, there’s a lawyer.

I probably wouldn’t have done this myself because when I think “lawyer,” I think “boring.” Especially a patent lawyer. But Moore treats his lawyer much like Tom Cruise’s part in A Few Good Men (not surprisingly, an Aaron Sorkin creation), where he plans to get Edison in court and force him to admit he cheated on the patent.

And that’s all well and good. But what I like about Moore is he has the ability to surprise you in a genre that’s plagued by its plainness.

Halfway into the story (spoilers), Westinghouse loses the patent battle to Edison. That’s right, HE LOSES. Not only is this a great plot beat (we’ve lost the battle with half the script remaining. Everyone’s asking, where do we go now??), but it allows Moore to introduce a third character.

Nikolas Tesla.

And I will tell you right now. Whoever plays this part is going to be a breakout star (unless he’s already a star). Moore goes so kooky with Tesla that you can’t look away from him. There’s a great little screenwriting tip here. Give a character a DEFINING ACTION, and if that action is strong enough, we’ll know exactly who that character is for the rest of the script. Moore focuses on Tesla’s “weird wave.” He keeps making this weird uncomfortable wave around people, and it perfectly embodied his oddness.

Tesla’s created a different kind of electricity that would not be bound by Edison’s patent. But Tesla’s a wild card. He’s got zero infrastructure. So Paul tells Westinghouse, who does have infrastructure, to team up with Tesla on his bid. The two become an unlikely pair with a common goal. Take out Edison.

Whenever you write biopics – hell, whenever you write a script – you need CHARACTERS. This is something it took me years to figure out. I was always a plot junkie. I thought fun stories, cool twists and great set pieces were the key to writing a great script.

But, in reality, it’s the characters. Because characters are interesting on their own. You can place a good character in a mediocre scene and we’ll still be drawn to him. Thomas Edison is a great character. He’s a fucking asshole. He’s full of himself. The man SUED HIS OWN SON! Whenever you put that guy in a scene, we pay attention.

Nikolas Tesla is a great character. He’s quirky, he’s weird, his mangled English leaves you scratching your head every time he speaks. The surprise element of Tesla makes him a fascinating character to watch as well. We never know what he’s going to do next.

Now here’s where the character argument gets interesting. Somebody in your script has to be the straight man. They’re the person who grounds the script. In most cases, this will be the hero. As a result, your hero ends up being the most challenging character to write. How do you make this person as interesting as an asshole, or a weirdo?

This is where a screenwriter earns his mettle. Because it isn’t easy. However, there are little things you can do to make us care. For starters, you can make your hero extremely determined. Audiences love determined people. You can make him an underdog. Audiences love rooting for the underdog.

Admittedly, these are “straight man interesting traits,” and therefore will never be as fun to watch as an outlandish part. But played right, we’ll be invested in the character’s journey. You can then use the orbiting characters to add a dose of spice to the story.

Of course, you don’t HAVE to make the main character the straight man. Alan Turing in The Imitation Game was offbeat. The same thing can be said for Jordan Belfort in The Wolf of Wall Street and John Nash in A Beautiful Mind. So it’s all a matter of whose story you’re telling and who’s point of view you want to tell it from.

As for the rest of the script, Moore includes some classic screenplay elements. We have a ticking time bomb – everything must be done before the World’s Fair. We have the “impossible task” (we’re told at the beginning that Edison’s lightbulb patent is one of the most airtight patents in history). We have that conflict I referred to. You can feel the weight of these two titans crashing down on the plot at all times.

The only problem I had with the script was the beginning. I didn’t understand why the heads of the firm were trying to get Westinghouse to pull out of a legal battle with Edison. Since when has a law firm ever turned away the money of its rich clients? That felt a bit forced to me.

But outside of that, this script was as bright as its subject matter. Moore has proven, once again, that he’s a hell of a screenwriter.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[x] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Make sure to remind your audience that your hero’s task is impossible. Hearing someone say, “Edison’s patent is the most airtight patent in history,” prefaces just how difficult the journey will be. Had this line not been written in, I wouldn’t have realized just how much of an uphill battle this was.