Search Results for: the wall

Genre: Drama

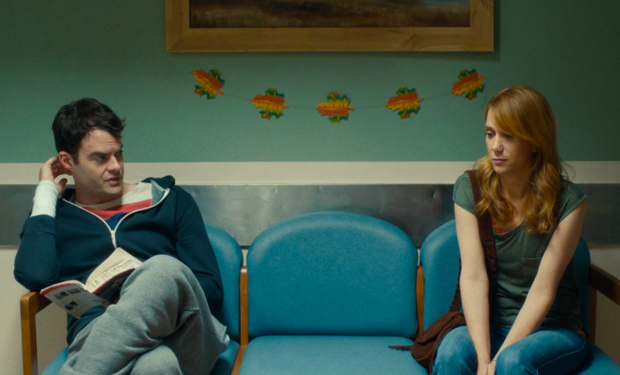

Premise: When 30-something Milo tries to commit suicide, his estranged sister, Maggie, invites him into her home, where the two start the process of healing old wounds.

About: Writer/director Craig Johnson graduated from NYU film school a decade ago, where he originally conceived of this idea with fellow student Mark Heyman (who wrote Black Swan). The two eventually went their separate ways, coming back to the script only recently, where they re-focused it on its best asset, the brother-sister relationship. Johnson has one other movie under his belt, the little seen True Adolescents, which starred Mark Duplass. He’d been trying to get Skeleton Twins made for awhile with different packages, but it wasn’t until Kristin Wiig came on that he finally believed the movie would get made. And it did!

Writers: Mark Heyman and Craig Johnson

Details: 93 minute runtime

I actually saw two movies this weekend. The Skeleton Twins and The Maze Runner. For The Maze Runner, I tried to bring a little of that “opening day enthusiasm” typically reserved for movies like The Avengers and Star Wars. So I lugged in a big block of cheese. ‘Cause it was a maze? Like rats in a maze? The theater ushers didn’t understand the joke and told me I either needed to eat the cheese, throw it away, or not see the movie. I sighed and threw it away.

The cheese turned out to be relevant in a different way in that most of Maze Runner was cheesy as hell. Even worse, it employed the classic screenwriting mistake of making the main character ask 60 million questions: “What is this place?” “Where are those guys going?” “What happens in there?” “What’s a runner?” “What’s that noise?” “What happens if they don’t come back?” “What’s a Griever?” Word to the wise – if your main character is always asking questions, he doesn’t have any time to, actually, you know, do stuff.

The movie really wasn’t that bad. It was just generic. I hate giving that note to writers cause it sounds so vague but it’s so often the problem. Every choice feels like the first choice the writer came up with. A maze that changes. Seen it before. Spiders inside the maze? That must’ve taken a while to come up with. The lovable underdog fat kid. Oh, and let’s not forget the dialogue (Mopey character who thinks he’s going to die: “Take this [trinket] and give it to my parents when you get out of here.” Hero gives the trinket back to mopey character. “No. You’re going to give it to them yourself.”).

But the biggest faux pas is something you just can’t screw up as a screenwriter. You have to give them the promise of the premise. If you’re writing a script about a giant maze, that maze better be fucking a-maze-ing. And this one wasn’t. It basically amounted to tall ivy-covered walls with giant spiders running around in them. That’s it?? Your maze boils down to Wrigley Field meets Harry Potter?

Lucky for me, I also got my suicide on this weekend. But before I get to Skeleton Twins, I have to do some name-dropping. It was Friday night at the Arclight in Hollywood. As Miss Scriptshadow and I were heading to our theater we saw none other than KEVIN SMITH barge through the lobby (he was moving like a cannonball). I remembered that his movie Tusk was opening and figured he was going to watch his own movie. Which is kind of strange but also kind of cool at the same time.

The funniest part was as he walked through, every single person turned (around 100) and whispered, “That’s Kevin Smith. Hey, that’s Kevin Smith. That’s Kevin Smith.” I guess if there’s one place Kevin Smith is going to be a mega-celebrity, it would be at a cinema-loving theater like Arclight in Hollywood.

Anyway, we rode that excitement wave right into our suicide film, which I was only seeing because it got such a high score on Rotten Tomatoes (I’ll see anything above 90%). Usually I despise films like this. Depressed indie people being depressed, trying to commit suicide, then being more depressed. Count me out. But lo and behold, this ended up being one of my favorite films of the year!

30-something siblings Maggie and Milo haven’t seen each other for ten years. Coincidentally, on the exact same day, they both try to commit suicide. Maggie gets the call about Milo being at the hospital before she can off herself, so she goes there and asks Milo to come live with her and her husband, man-child but sincerely lovable Lance, until he feels better.

Over the next few weeks, Milo, who’s gay, reconnects with an older man whom we find out was his teacher in high school. In the meantime, we find out that Maggie, who’s trying to have a baby with Lance, is secretly taking birth control so she doesn’t have a child. She’s also banging her scuba instructor, which I guess makes the birth control a “kill two birds with one stone” type of deal.

We eventually learn that the siblings’ self-destructive ways stem from their own father jumping off a bridge when they were just kids. It seems, for all intents and purposes, that they’re just following the script, doing what daddy did. So the question becomes, can they put the past behind them and move forward? Or are they on a collision course with fate, one they have no control over?

First I lauded a script about two cancer-stricken teenagers earlier this year. Now I’m touting suicide entertainment. What’s wrong with me???

Not only was The Skeleton Twins good, but it succeeded where many other an indie film have failed. You see, when you don’t have a clear plot (like The Maze Runner – “Get out of the maze”), the story can easily get away from you. Without that big plot-centric protagonist goal, it’s not always clear where you’re supposed to take the story.

Well, in character-driven screenplays, like this one, the point shifts from achieving a goal to resolving relationships. That’s it. That is what’s going to drive the reader’s interest or not drive it. You create 3-5 unresolved relationships – characters with a big problem between them – and then you use your story to explore those problems. If the problems are interesting and you explore them in an interesting way, we’ll stick around to see what happens. Here are the four main relationships in The Skeleton Twins…

1) Maggie and Lance – she’s not sure if she wants to be with him.

2) Maggie and her scuba instructor – she’s trying to end the affair but can’t.

3) Milo and the old high school instructor – their relationship was cut off when they started it in high school. They have to figure out where it is now.

4) Milo and Maggie – they still have a few things from the past to resolve.

The other big thing you want to do with these non-plot-heavy indie movies is throw a lot of plot points at the story. Remember, we don’t have that big goal at the end to drive the film (Win the Hunger Games!), so you have to, sort of, distract us from that.

The Skeleton Twins does a great job of this. Maggie and Milo’s mom (whom they both hate) shows up unexpectedly. We find out Maggie’s hiding birth control. Maggie has an affair. We find out Milo had a relationship with his high school teacher. Lance finds out Maggie’s been on birth control this whole time they’ve been trying for a baby. Maggie ironically forgets to take the pill, discovers she’s late for that time of the month. I mean, for a tiny indie movie, there’s a lot of shit happening here. And that’s the way you have to do it with these indies.

I think lots of writers believe that because it’s an “indie” they need to show 20 minute shots of characters forlornly looking out at the sunrise set to an 8 minute Iron and Wine song set on repeat. There are a few of those shots in here, for sure. But the reason The Skeleton Twins succeeds where all these other indies fail is because it really packs a lot of plotting into its 90 page run time. There’s never something not happening.

On the non-screenwriting front, it was genius to cast comedians in these roles. This movie would’ve crumbled under the weight of two dramatic actors playing ultra-dramatic roles. The reason the film never falls too far into depression-ville is because of the dry offbeat humor Wiig and Hader keep slipping into their performances. Even Luke Wilson was great as the husband. Both funny and sympathetic.

This was a hell of good film. I should’ve saved my block of cheese for it.

THE MAZE RUNNER

[ ] what the hell did I just watch?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the price of admission

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

SKELETON TWINS

[ ] what the hell did I just watch?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the price of admission

[x] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Small indie movies need a lot of PLOT POINTS. You need to keep throwing things at the characters or revealing secrets to keep the story moving and alive. Go too long without anything significant happening and your script gets pulled into that “indie boring void” that so often dooms an indie film. Don’t become another one of those indie films.

All this week, I’ll be putting one of YOUR dialogue scenes up against a pro’s. My job, and your job as readers of Scriptshadow, is to figure out why the dialogue in the pro scenes works better. The ultimate goal, this week, is to learn as much as we can about dialogue. It’s a tricky skill to master so hopefully these exercises can help demystify it.

This first scene needs little setup. It’s the first scene in the script, takes place in a restaurant, and has three characters, Johnny, Tony, and Paul.

JOHNNY, TONY, and PAUL are sitting around a table. Johnny’s suit jacket is slung over the back of his chair. They are all enjoying a small meal. Each man wears a red tie to signify their allegiance to their gang.

JOHNNY: You’re a fuckin’ moron aren’t you?

TONY: That’s a little harsh don’t ya think?

JOHNNY: No I think it’s the right word. There’s nothing wrong with robbery. Stealing is a gift handed down to us by our forefathers.

Tony answers sarcastically.

TONY: Is that fucking so?

JOHNNY: Yes, Tony, it’s fucking so. And if you don’t shut your lips for a second I’m gonna sew ‘em up.

PAUL: Hey, hey, Johnny, calm down.

JOHNNY: Hey Paulie relax. Don’t make this fucking personal. Anyway, do you know how much we paid for Manhattan Island?

Tony doesn’t answer.

JOHNNY (CONT’D): Five bucks. We spent five bucks on this ashtray and now it’s one of the biggest commerce centers of the entire world.

TONY: So what, at least they got something. I never left a five spot in a safe I just robbed.

Johnny rubs his eyes.

JOHNNY: Tony, Tony, you fucking idiot.

Johnny turns to the window behind him.

JOHNNY (CONT’D): Tony, you see your fucking Jaguar out there.

A Jaguar rests in the parking lot.

JOHNNY (CONT’D): Now imagine not knowing what the potential of a car was then being offered a buck for it. You don’t know any better so you take the offer, then I turn around and make a fortune, I’ve just stolen your fortune.

TONY: Yeah but if I didn’t know–

JOHNNY: It doesn’t matter. In the constitution it says that I am guaranteed life, liberty, pursuit of happiness. And how is happiness achieved in this materialistic world.

PAUL: Money.

John rubs Paul’s head.

JOHNNY: That’s right Paul, and if I have to steal to get the money that makes me happy then I’m gonna steal my mother fucking ass off.

TONY: All I was sayin’ is the plan better be tight.

JOHNNY: And just how long have you been doing this?

PAUL: Oh shit Tony, not again.

Tony looks at Paul like he doesn’t know what he’s talking about.

TONY: No, no I was just sayin’.

JOHNNY: You were just sayin’ what? What was it that you just so happened to say?

TONY: I just wanted to make sure that everything was accounted for. That all things were taken into consideration.

JOHNNY: So you’re the fucking Don now?

TONY: That’s not what I’m sayin’.

JOHNNY: Alright was there another ceremony? Are you a made man now?

TONY: No.

JOHNNY: But I am so everything I say goes. If you have a problem with that I can get you a nice pair of cement boots and you can take it up with a flounder.

Johnny pulls a folded piece of paper out of his jacket and opens it.

JOHNNY (CONT’D): Alright, so…

TONY: Alright, but Johnny…

PAUL: Tony just shut up.

TONY: What I was just sayin’…

PAUL It don’t matter.

The next scene takes place in a ratty cocktail lounge. 50 year old Billy Batts, wearing a cheap out-of-date suit, used to be a big shot gangster. He’s since spent a long time in prison and just got out. A sharply dressed HOOD approaches Billy with his girlfriend. This is the first scene in the script (it would later be moved).

HOOD: Billy. You look beautiful. Welcome home.

BATTS: (laughing and turning to the bartender): What are you having. Give’em what they’re drinking.

We see four other men, including HENRY HILL and JAMES CONWAY, standing near Billy Batts at the bar, raise their glasses in salute. TOMMY DEVITO and another beehive blonde enter. Billy Batts looks up and sees Tommy.

BATTS: Hey, look at him. Tommy. You grew up.

TOMMY (preening a little): Billy, how are you?

BATTS (smiling broadly at Tommy and the girl): Son of a bitch. Get over here.

Tommy walks over and Billy, too aggressively, grabs Tommy around the neck. Tommy doesn’t like it.

TOMMY (forcing a laugh): Hey, Billy. Watch the suit.

BATTS (squeezing Tommy’s cheek, a little too hard): Listen to him. ‘Watch the suit,’ he says. A little pisser I’ve known all my life. Hey, Tommy, don’t get too big.

TOMMY: Don’t go busting my balls. Okay?

BATTS: (laughing, to the crowd at the bar) Busting his balls? (to Tommy) If I was busting your balls, I’d send you home for your shine box.

Tommy’s smile turns to a glare as he realizes Billy is making fun of him. The men at the bar are roaring with laughter. His girl is looking glumly at her shoes.

BATTS (to the hoods at the bar): You remember Tommy’s shines? The kid was great. He made mirrors.

TOMMY (almost a threat): No more shines, Billy.

BATTS: Come ooonnn. Tommeeee. We’re only kidding. You can’t take a joke? Come ooonn.

We see that Tommy is still angry but begins to relax with Billy’s apparent apology, but as soon as Billy sees that Tommy is beginning to relax, he contemptuously turns his back on Tommy.

BATTS (facing the bar): Now get the hell home and get your shine box.

Henry quickly steps in front of Tommy who is about to explode. Batts is facing the bar and does not see just how furious Tommy has become.

HENRY (gently wrestling Tommy away from the bar): Come on, relax. He’s drunk. He’s been locked up for six years.

TOMMY: I don’t give a shit. The guy’s got no right.

HENRY: Tommy. He doesn’t mean anything. Forget about it.

TOMMY (trying to wrestle past Henry): He’s insulting me. Rat bastard. He’s never been any fuckin’ good.

HENRY: Tommy. Come on. Relax.

TOMMY (to Henry): Keep him here. I’m going for a bag.

Today’s comparison is kind of tricky. One could make the argument that the dialogue in the first scene, from our amateur writer, is better than the second, which is a scene from Goodfellas. It’s more colorful. More varied. The characters play off each other well. You don’t find any fun lines like, “If you have a problem with that I can get you a nice pair of cement boots and you can take it up with a flounder” in the Goodfellas scene.

And this is where discussing dialogue can be confusing. Because there are two big problems with the amateur entry that keep it from being as good as the professional one. The first is that the ultimate goal of the scene (and the characters) is weak. Johnny is trying to convince Tony and Paul to rob something with him.

We’re occasionally strapped with scenes that have weak goals in our scripts, but it’s our job as writers to identify that problem and come up with a solution, some way to counteract this weakness and still make the scene interesting. In this case, the writer made a crucial mistake. He set the scene at a table. People sitting around tables talking is really hard to make interesting. So you’ve strapped an already weak situation on top of an unintereseting one.

Writers are aware when they do this either consciously or subconsciously, but instead of doing the hard work and rethinking the scene, they try to write flashy fun dialogue in the hopes of masking the problem. If you’ve ever rewritten the dialogue a hundred times in a scene and it’s still not working, this is usually the problem. It’s not that the dialogue isn’t working. It’s that the underpinnings of the scene aren’t working.

The second problem is that there’s no conflict in the scene. Well, there’s a little conflict. Johnny’s giving the others a hard time. But true conflict requires consequences. If Paul and Tony act up, the worst you suspect Johnny will do is curse them out. Which means that you have a dialogue scene with no conflict. And no conflict means no tension, and no tension means no drama.

Let’s switch over to the second scene now. Notice how the dialogue is serving a purpose. The two main characters have goals. Each one is posturing, trying to be seen as the bigger man in the room. The stakes are high because this is very important to both of them, especially Tommy, who’s upset that Billy doesn’t realize he’s a big shot now.

Because our two characters have clear goals with high stakes attache, and that those goals contrast one another, you have conflict/tension between them. Compare the tension in the second scene to that in the first. It’s WAY higher, right? That’s because the writer put the elements in place ahead of time to ensure he’d get the most amount of conflict in the scene. And conflict is one of the huge keys to good dialogue.

This is one of the big things I’m realizing this week. The pros are laying the foundation for the scene first – how they’re going to make it build and pay off – then they lay the dialogue on top of that. The amateurs are just laying the dialogue down right away. It’s like putting a rug on a dusty dry-wall floor. The rug itself may be pretty (like all the fun banter in the first scene) but it doesn’t look right inside an unfinished room.

Now some of you may say this is another apples to oranges comparison. One scene has characters who are going to kill someone and the other just people talking. So clearly the more intense scene is going to win out on the drama-meter.

This is something else I’m trying to convey this week. The Goodfellas writer never would’ve written the first scene. He knows that three people sitting down at a table with no internal or external conflict is a recipe for boredom.

Think about it. Before the Goodfellas scene was written, the writer was faced with a choice of how to introduce these characters. He very well could’ve put Henry Hill, Tommy, and James at a table and let them chat. Maybe show how impatient Tommy was with the waiter to convey his anger issues. But he knew that no matter how well he wrote that scene, it didn’t have anywhere to go.

So instead, he creates an outside source of conflict, Billy Batts, pitts one of our guys against him, and now we have ourselves a scene. We’ve got conflict, we’ve got tension. We’ve got a scenes that BUILDS. That’s a scenario you can draw a lot of good dialogue from.

Knowing all this, how would I improve the first scene? Well, outside of writing a completely different scene, I’d look for a source of conflict, either inside the group or outside the group. That’s one of the easiest ways to boost dialogue.

Maybe there’s a table of super-rowdy drunk college kids next to them. Johnny can’t seem to get through his sentences without another outburst of laughter drowning him out. With each outburst, he gets more and more pissed off. Maybe at one point, a kid gets up from the table and stumbles into Johnny. Doesn’t even apologize, just walks off. Notice how we now have a scene that’s BUILDING, that has suspense, like the Goodfellas scene, as we know Johnny is going to deal with these kids at some point, and it’s going to be good. That’s one example. Now you try. What source of conflict would you use?

What I learned: Create an audience for your characters to add a different dynamic to the conversation. One of the reasons the Goodfellas scene plays so well is because it isn’t just a scene between Batts and Tommy. If that was it, Tommy might have let it go. It’s that Batts has brought in an audience. His insults aren’t intimate. He’s performing them in front of others so that they sting Tommy even harder. Writers often get wrapped up in just the two characters featured in a scene, not realizing that bringing in one of the dozens or hundreds of characters around them could give the scene a fresh new energy.

All this week, I’ll be putting one of YOUR dialogue scenes up against a pro’s. My job, and your job as readers of Scriptshadow, is to figure out why the dialogue in the pro scenes works better. The ultimate goal, this week, is to learn as much about dialogue as we can. It’s such a tricky skill to master and hopefully these exercises can help demystify it.

Our first scene introduces us to Boyd, a washed up cop, and Dominique, a drug addicted jazz singer. Boyd has just driven Dominique home from the station after she was released from a solicitation charge. As she gets out, she invites him up to her apartment for a drink. This is where the scene takes place (in the apartment). Outside of the car ride they just shared, this is their first conversation.

Boyd grabs a bottle of the good stuff off the makeshift bar.

DOMINIQUE: Not that one. That one’s for show.

Fishing inside a cabinet, Dominique produces the exact same bottle. She pours them both a drink.

Curious, Boyd sniffs his bottle, then sniffs what she’s poured. He smiles knowingly.

BOYD: Thanks.

Dominique’s on one side of the large canopy bed. Boyd’s miles away, on the other side. Morning light creeps around the drapes.

BOYD: I saw you once.

DOMINIQUE: Don’t be coy, detective. I see you in the back, watching me. You think I don’t, but I do.

BOYD: One, remind me to pick a new spot. And two, it was a long time ago, Chicago. A club called Mister Lucky’s.

DOMINIQUE (playful): What do you know about Mister Lucky’s?

BOYD: I knew talent when I saw it.

Dominique blushes.

BOYD: Which makes me wonder –

DOMINIQUE: What’s a girl like me doing working at Club Cake?

BOYD: Something like that.

DOMINIQUE : Atoning for my indiscretions. And you? What kind of cop’s moonlighting for an asshole like Q?

BOYD: They say true success is knowing your limits and not letting others burden you with their expectations.

DOMINIQUE: What’s that? Some new age, 12 step bullshit?

BOYD : My way of saying we have a lot in common. Boyd raises his glass.

BOYD: To indiscretions and atonement.

They toast.

DOMINIQUE: I’d thought it’d get easier.

BOYD: So did I.

DOMINIQUE : Daisy said you were a good guy. Are you?

BOYD: When I’m not burdened by expectations? — Yeah.

DOMINIQUE : I’ve got enough pricks in my life. I could use a friend with no expectations.

BOYD: Then I’m your man.

Biting her lip.

DOMINIQUE: Come on.

Dominique steps out of the ripped dress. Boyd’s eyes follow long legs and firm ass down the hall.

DOMINIQUE: Bring the bottle.

BOYD: Where are we going?

DOMINIQUE: To bed.

Sitting on the large canopy bed, Boyd’s confused. Off his look.

DOMINIQUE: That one’s for show.

In this next scene, we have Tom, a homicide detective, paying a visit to Vanessa, a successful novelist who’s a person of interest in a murder case. The two have met before, but this is the first time Tom is seeing her alone. Her house is a huge, a mansion. The scene takes place up in her large office.

He follows her inside. He watches her body. His movements are tentative, off-balance. She turns [the music] down.

On a table by the window, he sees [a computer]. Spread around it are newspaper clippings. They are all about him. We see the headline on one: KILLER COP TO FACE POLICE REVIEW. She sees him glancing at the clips.

VANESSA: I’m using you for my detective. In my book. You don’t mind, do you?

She smiles. He looks at her, expressionless.

VANESSA: Would you like a drink? I was just going to have one.

TOM: No, thanks.

She goes to the bar.

VANESSA: That’s right. You’re off the Jack Daniels too, aren’t you?

She is making herself a drink. She takes the ice out and then opens a drawer and gets an icepick. It has a fat wooden end. She uses the icepick on the ice, her back to him. He watches her.

TOM: I’d like to ask you a few more questions.

VANESSA: I’d like to ask you some, too.

She turns to him, icepick in hand, smiles.

VANESSA: For my book.

She turns back to the ice, works on it with the pick. She raises her arm, plunges it. Raises it, plunges it. He watches her.

TOM (wary): What kind of questions?

She puts the icepick down, pours herself a drink, turns to him.

VANESSA: How does it feel to kill someone?

He looks at her for a long beat.

TOM (finally): You tell me.

VANESSA: I don’t know. But you do.

Their eyes are on each other.

TOM (finally): It was an accident. They got in the line of fire.

VANESSA: Four shootings in five years. All accidents.

TOM (after a long beat): They were drug buys. I was a vice cop.

A long beat, as they look at each other.

TOM: Tell me about Professor Goldstein.

Beat.

VANESSA: There’s a name from the past.

TOM: You want a name from the present? How about Hazel Dobkins?

She looks at him a long beat, sips her drink, never takes her eyes off him.

VANESSA: Noah was my counselor in my freshman year. (she smiles) That’s probably where I got the idea for the icepick. For my book. Funny how the subconscious works. (a beat) Hazel is my friend.

TOM: She wiped out her whole family.

VANESSA: Yes. She’s helped me understand homicidal impulse.

TOM: Didn’t you study it in school?

VANESSA: Only in theory. (she smiles) You know all about homicidal impulse, don’t you, shooter? Not in theory — in practice.

He stares at her a long beat.

VANESSA (continuing quietly): What happened, Tom? Did you get sucked into it? Did you like it too much?

TOM (after a beat): No.

He stares at her, almost horrified.

VANESSA (quietly): Tell me about the coke, Tom. The day you shot those two tourists — how much coke did you do?

She steps closer to him.

VANESSA (continuing): Tell me, Tom.

She puts her hand softly on his cheek. He grabs her hand roughly, holds it.

TOM: I didn’t.

VANESSA: Yes, you did. They never tested you, did they? But Internal Affairs knew.

They are face to face. He is still holding her roughly by the hand.

VANESSA (continuing): Your wife knew, didn’t she? She knew what was going on. Tommy got too close to the flame. Tommy liked it.

He twists her hand. They’re pressed against each other — their eyes digging into each other.

VANESSA: (continuing; in a whisper): That’s why she killed herself?

He is twisting her arm, staring at her, pulling her against him. We hear the DOOR behind them. A beat, and he lets her go, turns away from her.

Roxy stands there, staring at them. Her hair is up. She wears a black motorcycle jacket, a black T-shirt, and black jeans and cowboy boots.

VANESSA (continuing brightly): Hiya, hon. You two have met, haven’t you?

Roxy looks at Tom. Vanessa goes to her, kisses her briefly on the lips, stands there with her arm around her — both of them looking at Tom.

He walks by them, opens the door to go, his face a mask.

VANESSA (continuing): You’re going to make a terrific character, Tom.

He doesn’t look at her; he’s gone.

So what’s the big difference? The first scene is two people talking. The second scene is a SCENE.

What do I mean by that? Well, let’s take a look at the first scene. It’s not bad. But there doesn’t seem to be a clear goal for our characters. It’s more of a mish-mash of conversation interrupted by the occasional piece of backstory. “What’s that? Some new age, 12 step bullshit?” “My way of saying we have a lot in common.” Boyd raises his glass “To indiscretions and atonement.” “I thought it’d get easier.” “So did I.” “Daisy said you were a good guy. Are you?”

“I thought it’d get easier??” Where did that come from?? This seems to be the beginning of a new beat in the scene, a new segment of conversation, which is fine. You can switch gears in a scene . But the problem with this scene is that it never quite finds the gear it wants to cruise in. It feels like it’s always switching gears. This is usually due to the writer being unclear on what his characters want in the scene (their goal). If the writer doesn’t know what they want, he has the characters talk to fill up air, and that almost always results in bad dialogue.

I see a lot of beginners writing this way. They have a vague idea of where they want the scene to end (in this case: the characters having sex), but they haven’t thought about what each character wants that will lead them to that goal. So the dialogue essentially becomes a time-wasting feature until one of the characters says to the other, “Let’s go to bed.”

If, for example, Boyd really wants sex from this girl (his goal), you can play with that. It’s not going to be as strong as a detective probing someone about their role in a murder, but stakes are relative to the characters and the situation, and you can make some of the simplest goals feel important. For example, let’s say we make Boyd a sex addict (He doesn’t have to be. He can just be horny. But I’m raising the stakes a little). Boyd’s goal in this scene, then, is to have sex. Once you have a goal, you can create obstacles to that goal, and now you have conflict, which creates tension/drama.

The way the scene’s written now, Dominique is making it clear she’s going to have sex with Boyd no matter what. I mean she’s practically got it tattooed on her forehead. That means everything in the scene is a foregone conclusion, which is boring. Instead, what if Dominique is fucking with Boyd, just like Vanessa is fucking with Tom. One second Dominique is being flirty, the next she’s stonewalling Boyd. It’s driving him crazy. He doesn’t know if she wants him or not. By doing this, the GOAL IS IN DOUBT. And if the goal is in doubt, the dialogue has purpose. Because it means Boyd has to use his words (his dialogue) to get something.

The second scene is from Basic Instinct (I changed the character names in hopes that you wouldn’t know). Whereas our amateur scene just plopped its two characters down into a room, you can tell the scene in Basic Instinct was CONSTRUCTED. What I mean by that is that pieces were put into place to mine as much drama as possible from the scene.

The very first thing that happens is Tom sees the newspaper clippings of himself on the desk. This is significant because Tom thought he was coming in here as the dominant party. This switches things up. It means Vanessa has become the dominant player. These kinds of things always work – where you change the assumed dynamic between the players in the scene. A cop is supposed to be in charge around a suspect. But now, the suspect is in charge, and that gives the scene an exciting unpredictable energy.

Next, the scene has clear goals. Tom wants to find out information about the murder from Vanessa. Vanessa, on the other hand, her goal is to intimidate Tom. She wants him to know that if he’s going to look into her as a suspect, it’s going to come at a price. This creates a TON of conflict, which is the fuel for any great scene. Looking back at that first scene, I’m not sure I noticed any conflict.

Next, we have subtext. Tom’s not coming right out and saying “I think you’re the murderer.” That would be boring. He’s digging, he’s probing. Nor is she saying, “Don’t fuck with me, Tom! I will make your life miserable.” That also would be boring. She’s showing him that she’s looked into him. She’s crunching ice. She’s pushing his buttons.

Next, the scene builds. Each segment of the scene escalates the tension. The tension near the end of the scene is higher than the tension at the midway point which is higher than the tension at the ¼ point which is higher than the tension at the beginning. That’s good writing, when a scene builds up, when you feel that air being pumped into the balloon. Go back to the first scene again. Notice how ¾ of the way into the scene, the energy doesn’t feel that much different from the energy at the beginning of the scene.

Finally, Eszterhas (our writer) throws a little twist into the end, by having Roxy show up. It’s not a huge part of the scene, but it’s a calculated measure. Watching Vanessa flip the switch and become rosy and sweet shows how calculating she is, how easy it is for her to go from one extreme to the next, which is scary if you’re Tom.

There’s a lot more to talk about with both of these scenes, and I encourage you guys to point out what you find. And hey, if you want to rewrite the opening scene to show the writer how you’d make it better, by all means, go ahead. I’d be interested to see what you came up with. This week should be fun!

What I learned: Sitting two people down and having them talk is usually not enough for a scene. What Basic Instinct teaches us is that you should construct the elements of your scene in such a manner as to create and build tension.

Genre: TV show – Drama

Premise: A young ballet actress with a haunting past joins one of the top ballet companies in New York. Once there, she quickly realizes just how competitive the New York ballet scene is.

About: As it became harder for actress Moira Walley-Beckett’s to find acting roles (she had parts in over 35 TV shows), she transitioned into writing, joining writing staffs for a few failed shows before eventually finding a writing gig on the short lived but heavily hyped, Pan Am. That exposure helped her become part of one of the most famous writing staffs in history, that of Breaking Bad. Walley-Beckett actually wrote two of the most talked about episodes in the series – first, Fly, with co-writer Sam Catlin. And then Ozymandias, which is considered to be one of the best television episodes in history. Now that Breaking Bad is over, Walley-Beckett is heading out into the scary world of show creation, where she’ll be the big writer in the room. Does her pilot warrant this promotion? Let’s find out.

Writer: Moira Walley-Beckett

Details: 60 pages

One of the first things you want to look for with any idea is irony, as it continues to be the best way to sell a show/movie. A lawyer who can’t lie. A vegetarian chef opens the best steakhouse in the city. The ballet profession’s dirty little secret – that it’s the most abusive and cruel profession of all. Without irony, you’re forced to cram as much information about your show as possible into the logline to help the consumer get what’s unique about it. And no matter how hard you try, you can never seem to make it all fit.

Taking on ballet’s dirty little secrets felt right for a Breaking Bad alum. That writer’s room was used to dealing with dirty little secrets. But the ticket for this anticipation train comes with an asterisk at the top. Wasn’t this idea just done in movie form a few years ago in Black Swan?

I’m seeing more and more of this as scripted television continues its Big Bang expansion. Instead of looking for new ideas, writers are taking their favorite movies and simply turning them into TV shows.

Did you like Twister? Make a show about storm chasers. Neighbors? Make a show about a frat house. Lucy? Make a show about a secret agent who gets really smart. It’s gotten to the point where writers are being straight up lazy. And the only way lazy entries work is if you can bring something fresh to the idea. The fact that you didn’t work at all to come up with the idea in the first place sheds doubt on this possibility. But I’m going to hold out hope. I’d love to watch the ballet version of Breaking Bad.

When we meet 21 year old Claire Robbins, she’s running away in the middle of the night. What she’s running from is a mystery, but by the look on her face, you can tell it’s haunt-you-for-the-rest-of-your-life bad.

Claire escapes on a train and arrives in New York City the next day, where she knows a total of zero people. Luckily, Claire’s got one hell of a skill to fall back on. Girl can dance. So she heads to one of the best ballet companies in the city, snags an audition, and kills it. She makes it into the troupe.

If you don’t already know, ballet chicks are the most ruthless, the most jealous, the most nasty girls on the planet. Actually, I don’t know if that’s true or not. But that’s the way they were portrayed in Black Swan and since I base all my knowledge in life on movies, I’m assuming this to be fact.

When the other girls figure out how awesome Claire is, they get even more jealous. And when cut-throat bi-sexual troupe leader, Paul, decides to have her headline his next show, well, the jealousy hits an all time high.

Claire somehow makes a couple of friends, including Mia, who spends more time banging random hook-ups than breathing. And Daphne, who secretly works at a strip club in order to afford an apartment overlooking the Hudson River.

Unfortunately, that past she ran away from ends up finding her, a man she shares a terrifying secret with. Will she be able to handle the pressure of New York City and her elite ballet troupe, or will she falter and have to go back to her hometown, where, surely, this horrible secret will continue?

Well, let’s just get this out of the way. Flesh and Bone failed test number 1. It wasn’t fresh. This was almost EXACTLY like Black Swan. A timid little girl. A dance troupe where all the girls hate her. An overbearing troupe leader who uses his power for inappropriate means. The aging girl who sees the new girl as a threat to her spot. Our heroine gets the lead part. We even have a wild night out to a strip club, similar to the famous night out between Natalie Portman and Mila Kunis.

It’s a weakness every writer seems susceptible to. We fall in love with certain movies, and we want to make something similar. So we go in with the best of intentions, oblivious to the fact that our movie/show is the EXACT SAME THING as our favorite movie.

I mean we could literally write a beat for beat remake of Titanic and not know it until someone says, “You do know they already made a movie about the Titanic with a doomed couple that revolved around a missing diamond that sunk with the ship, right?” Ohhhhh, we think as we’re counting future box office receipts in our head. Yeah, I guess I didn’t consider that.

But if you’re able to move past the show’s common bond with the Aronofsky thriller, you’ll find some good stuff. What a TV show allows you to do is explore the more specific areas of a subject matter, enabling you to go beyond the classic movie beats into stuff like bleeding ballet shoes at the end of a dance, pulling an entire toenail off before the next session, and those dirty ugly locker room sessions before and after practice (girls stuffing paper towels into their no-no area because they forgot to bring tampons).

Also, a few of the characters are well-drawn. I liked the sex-crazed Mia. I liked secret stripper Daphne. This easily could’ve devolved into wall-to-wall darkness, which can drown a show (AMC’s “Low Winter Sun”). These two lit things up with their overbearing personalities, a nice contrast to many of the unscrupulous things happening elsewhere in the story.

In fact, there was enough good for me to almost give this a worth the read… until the ending. Now this is a huge spoiler, so turn away if you don’t want to know. But basically, a guy from back home keeps calling Claire throughout the episode, but she keeps avoiding him.

Finally, in the last scene, she answers, and we cut to the caller, Bryan, sitting in Claire’s bedroom back home. After a few exchanges, we realize that Bryan is Claire’s brother. And he’s beating off. To Claire. This is when we learn that Claire ran away from an incestual relationship with her brother. Cut to black.

Uhhhh…SAY WHAT!??

Where the HECK did this come from??? Where was this set up? What in King Joseph’s name happened earlier in the episode to indicate that incest was going to be a theme in this story?

I couldn’t believe that after a pretty well-written pilot, I witnessed a classic rookie mistake. The twist ending that has nothing to do with anything, and is only there for shock value. Twist endings need to be set up with a series of hidden clues to work. We get none of that here, turning the ending into a desperate gimmick rather than an “Oh my God!” moment.

To be honest, I think Moira could’ve saved this pilot with only a slight shift in her approach. One of the friend characters, Daphne, secretly moonlights as a stripper. Why didn’t Moira move this character angle over to Claire??? That’s a hook for a show. A girl at one of the most prestigious dance companies in New York moonlights as a stripper. There’s your irony. Now you have someone who has to hide that world while she becomes a star in the ballet world. I don’t know how long you could keep that going. She might have to quit stripping during the first or second season, but it’s a great place to start a character. Way more interesting (and relevant) than Incest Ballet Chick.

Not a badly written pilot at all. But a few questionable choices kept it from reaching its potential.

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: The “mystery box past” is a staple in television, and it’s a great way to hook your viewer for future episodes. You simply hint that something bad happened in your hero’s past, and if that something sounds dirty or scandalous or intriguing enough, the viewer will want to tune in for future episodes to find out what it is. We saw it with Scandal (the main character had an affair with the president), we saw it with Lost (with all the characters) and we see it here, with the incest shocker. I didn’t like the incest shocker, but the mystery box past is still a great tool to use when used well.

One of you suggested this in the comments the other day and it sounded like a wonderful debate. The two biggest geek shows on TV are Game of Thrones and The Walking Dead. My guess is that both shows have a lot of crossover viewers, which means most of you are educated enough to offer your opinion on both. Therefore, I shall ask: Which is the better written show, The Walking Dead or Game of Thrones? Notice I didn’t ask which is the “better” show, but which show is better written.

In my eyes, this isn’t even a fair fight. The Walking Dead is a much better written show. I’ve never felt more worried for characters than I do during this show. At any moment, they’re in danger from either a zombie or fellow human attack, which leads to that necessary discomfort the audience must feel in order for the story to work.

The scene-writing is also top-notch, always so clever. They’re constantly setting up complex situations that don’t have clear resolutions, keeping you on the edge of your seat for up to 10 minutes at a time. My favorite scene of the year (in anything!) is the one where Rick sends his son and Michonne out to get food while he takes a nap in an abandoned suburban house. In the interim, raiders show up and take over the house, forcing Rick to hide.

If he tries to leave, they’ll easily catch and kill him. If he doesn’t, his son comes home unaware the raiders are there and they’ll kill him instead. These are the best kinds of scenes because there’s no solution. Every road traveled leads to failure. And if you set up that kind of situation, you better believe your reader/viewers are going to stick around to see what happens. The Walking Dead is filled with cleverly thought-out scenes like this.

Like any show, The Walking Dead has some good characters and some not so good characters. But on the whole, they’re good. Watching Rick fight a daily battle against losing his humanity is one of the better inner conflicts I’ve watched a main character go through. Watching inventive characters like the zombie-carrying sword-wielding Michonne emerge is beyond delightful. And meeting the best villain of the last decade in the endlessly complex “The Governor” was the cherry on top of Season 3.

Finally, The Walking Dead is really good at structuring its storylines. There’s almost always an episode goal (Find a way out of the house without the Raiders seeing you), a season goal (Get to the safe city, Terminus), and a series goal (survive and find ultimate safety) to keep everything focused and on track. There’s never a point in The Walking Dead where you’re saying, “Wait, what’s going on again?” It’s always clearly laid out.

Game of Thrones is a completely different animal, but good in its own ways. Its number 1 asset is its mythology. With The Walking Dead, the mythology is being built as we experience it. There’s not a lot of mystery there. But some of the things affecting the characters in Game of Thrones go back thousands of years. For that reason, you feel like you’re living in a truly immersive world, and every episode is a gift you get to unwrap to find out more about that world.

Another reason I love Game of Thrones is its restraint. Unlike certain fantasy franchises that throw a million pieces of fantasy at you a minute (orcs, spells, invisibility, giant spiders, talking trees), Thrones TEASES their fantasy elements. We hear about dragons, White Walkers, people coming back from the dead. But because these things are only hinted at, we don’t grow numb to them after five minutes. Instead, we eagerly anticipate when we’ll get to see them, which is another reason we’re so excited to keep watching.

Also, the relationships the show creates are captivating. Every character is connected to every other character in some way. To give you a taste, Cersei Lannister, the Queen, is secretly sleeping with her brother Jaime Lannister. We later find out that the three children the King and Queen have are not the King’s. They’re all from Jaime, which makes them inbreds. One of these children, the evil, unstable Joffrey, becomes King. Rumors spread throughout the land that Joffrey is the inbred son of Cersei and Jaime. Cersei must do everything in her power to keep this information from getting to Joffrey, since unstable kings who find out that they’re inbred probably aren’t going to take it well.

Finally, there are a lot of standout characters on the show. The empowered “mother of dragons,” Khaleesi, is exciting to watch as she goes from underdog outsider to plotting her Iron Throne takeover. Tyrion, the “imp,” played by Peter Dinklage, is lovely to watch if only because the character is so unexpected. Occasionally he’ll play the coward, only to follow it up by slapping the king. Arya Stark, the young daughter of the slain Ned Stark, is pulled from her family and must survive out in the wild. There’s the impossibly cold Cersei Lannister, whose utter hatred for the world drives her every action. Her son Joffrey is so evil, you can’t look away, lest you miss him chopping someone’s head off. The always manipulative brothel owner, Littlefinger, charms with his whispering schemes and careful chess moves in order to keep his place in power. There’s always a character to look forward to here.

But here’s why Game of Thrones doesn’t compete with The Walking Dead. Whereas The Walking Dead is always clear – we always know what’s going on and can therefore participate in every aspect of the story – Game of Thrones is too often confusing. And it all comes back to one issue – there are too many characters.

In a show like this, a show that DEPENDS on you knowing the intricate details of every relationship, being confused about who’s who can destroy the enjoyment of an entire episode. If I’m only just remembering that Robb Stark wants to kill Character A at the end of a scene where two characters are discreetly talking about Character A, I’ve missed the whole point of the scene. This happens a lot in Game of Thrones.

Tons of characters also means entire episodes go by without us seeing some of the characters. So when we finally come back to them, we barely remember what they’re up to. Again, two or three scenes may go by before we recall what they’re doing in this location in the first place. For example, I was watching Jon Snow traverse the North Mountains for an entire episode before I remembered, from a couple of episodes ago, why he was sent there in the first place.

No matter how you spin it, this is bad writing. One of the requirements of writing any story is that the reader always understand what’s going on. If they don’t, it can only be because you, the writer, don’t want them to for some reason. In other words, it’s the writer’s choice. But a lot of the confusion that comes from Game of Thrones is not due to the writer’s choice. It’s due to there being too many characters and too many camps to keep track of.

Another problem with Game of Thrones is that it errs on the side of “telling” instead of showing. It’s gotten better at this as the show’s gone on. But in the first season, there were endless scenes where two people were in a room talking. Therefore, instead of seeing troops move across the land, we hear two people TALK ABOUT troops walking across the land. Indeed, every other scene appears to be strictly exposition, which would often grind the show to a halt.

What’s interesting is that this exposition is a result of choices the writers made a long time ago. If you’re going to have a dozen factions all vying for the throne, you’re guaranteeing you’re going to have a ton of exposition. The Walking Dead doesn’t have that kind of complexity in its endgame. The endgame is simply, “survive,” so its exposition is often minimal, and we can focus more on the fun stuff, which is showing and not telling (characters getting into dangerous situations and then trying to get out of them).

Personally, I think both shows are great in their own way. But The Walking Dead is a cleaner more action-oriented story that can just “be,” whereas Thrones has to talk you through much of its world to get to its payoffs, which can sometimes feel like work.

What do you think? Which is your favorite show and why? Make sure to support your opinion with valid points about the writing. And yes, this may be the nerdiest post I’ve written this year.

note: I’m on Season 2, Episode 5 of Game of Thrones. Please note spoilers in your comments!