Search Results for: the wall

Genre: Drama

Premise: A record executive in the 1970s suffers a mid-life crisis and goes back to his roots, hunting out new talent for his dying record label.

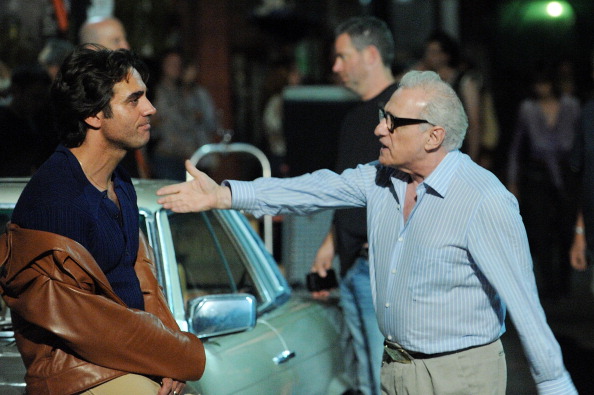

About: With Boardwalk Empire ending, Martin Scorsese and Terence Winter needed a new show to do for HBO. Enter rock n roll! And because it’s Scorsese, you better believe it ain’t set in modern day. Part of me thinks Scorsese hasn’t reached 2014 yet. He’s about 30 years behind us. So for him, he’s actually directing contemporary cinema. As for Terence Winter, besides creating Boardwalk Empire, he also wrote Scorsese’s The Wolf of Wall Street, a bunch of Sopranos episodes, the 50 Cent movie Get Rich or Die Tryin’, and even a couple of episodes of Xena: Warrior Princess.

Writer: Terence Winter

Details: 59 pages (Revised Draft, April 4th 2013)

Bobby Cannavale will star in the new HBO project

Bobby Cannavale will star in the new HBO project

Do I think Scorsese repeats himself a little too much? Ummmm, maayyyy-be? I mean, he definitely has a formula down for how he tells a story. And back in the day, when that approach was new, it was fun. But now, because it’s the only thing he does, you feel like you know all the beats of his stories before he does. Once the viewer is able to predict everything, there’s no reason to keep watching.

When you couple that with rock and roll as a subject matter, you’re walking on thin ice. Rock and roll is SO hard to do well because cliché is woven into its DNA. There’s a reason “sex, drugs and rock and roll” is one of the most popular phrases in history. Those things are always lumped together and as a viewer, there are only so many times you can see a musician ruining his career with drugs.

You gotta find a different way to do it. And, as I mentioned, with Scorsese directing, I was worried whether that could happen or not. Still, I held out hope that I’d be surprised. Let’s see if I was.

It’s 1973. 40-something Richie Finestra is a record exec at the dying American Century Records. The last remaining big band they have under their label is Led Zeppelin, and it looks like they’re going to jump ship too.

At American Century, we meet Richie’s team, which includes a combination of young A&R kids who aren’t finding enough new music and a bunch of middle-aged guys who are trying to hold onto the past.

Over the course of the pilot, we experience a group of flashbacks, when Richie was an up-and-coming exec, as he signed a talented young black musician named Lester. Richie promised Lester that if he made an album for him, he’d let Lester record an album of the music he loved, which was Blues. But that never happened, and now, sadly, Lester has become Richie’s driver, his musical dreams long forgotten.

As the days pass, Richie finds himself more and more frustrated with the direction of the company, and decides to make a radical change. He demands a divorce from his wife. Then he downgrades his position at the company to talent scout. He’s going back out there and do what these young bucks can’t – find music.

But the plan is thrown for a loop when Richie finds himself at the home of a couple of business associates and things get out of hand. During a fight, one of the men is accidentally killed, and Richie and the other associate decide to toss him into an alley in the hopes that the cops will think someone mugged him. Needless to say, a homicide detective shows up at Richie’s work the next day asking questions. We’ll see just how long Richie and his secret can last.

Okay, first question. Was it cliché? Yes. Pretty much every character here did some kind of drugs. Just once – ONE TIME – I’d like a character in a music movie not to do drugs. A character who shuns it. What’s the harm? Having one original character in this world? Because I’m pretty sure not EVERYBODY did drugs in the 70s. Although if they did, it would at least explain the fashion of the time.

The story itself was okay I guess. When you’re doing a period piece, you’re doing historical fiction. And when you’re doing historical fiction, you’re trying to educate (in an entertaining way) the viewer on the subject matter, whether it be casinos, money, the mob, whatever.

So I was really looking forward to learning new things about rock and roll in the 70s. I was disappointed. There’s nothing new here if you’ve seen Cameron Crowe’s Almost Famous. And that’s not good. With a movie, you only have a limited amount of time to get into details. With TV, you have an unlimited amount of time. TV thrives BECAUSE of the details. I get that this was just the pilot, but seeing a hot young singer bang a chick then pull out a heroin needle and shoot up, or watch two executives binge on coke until they were clueless… I saw that stuff 40 movies ago.

And it’s tough. I realize that you have to show SOME drug use since it’s rock and roll in the 70s. But there’s got to be a more original way to do it.

The one original and memorable aspect of the pilot was the Lester storyline. You know right away something’s up with Richie’s chauffeur, since we never see his face. And you know pretty quickly that this up-and-coming singer in the flashbacks, Lester, is probably him. So the dramatic irony feeds this aspect of the story. We know Lester’s career is doomed from the get-go.

But I thought RICHIE was going to be the one to screw him over. In the pilot, it’s nobody’s fault. Stories become more interesting when your protagonist’s’ choices drive the drama. So if our main character isn’t responsible for this man’s dried up life, then where’s the conflict?

And I don’t like mushy main characters, protagonists stuck in that boring middle-ground. Jordon Bellforte (The Wolf of Wall Street) isn’t KIND OF a greedy crazy asshole. He IS a greedy crazy asshole. I wanted Richie to have more wrong with him. I wanted him to be that record exec who rips off artists for his own personal gain. He’s done it his entire life and finally, now, he reliazes it’s wrong. He wants to change. Instead, Richie has no conviction. He’s not responsible for much of anything that’s wrong here. He’s just around.

In the end, I’m looking for three things from this kind of TV show. I want to learn something new about the subject matter (we learn the intricate nature of how casinos work in Casino), I want strong interesting characters that I care about (like Henry Hill in Goodfellas), or I want a cool story. There were little flickers of that stuff here (a quick scene about how a record contract works, the Lester storyline, the murder) but for the most part, this felt like a retread of stuff we’ve already seen. I couldn’t get into it.

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Inner conflict. You have to look at your character and ask, “What is the main conflict within this man?” “What is the thing he’s at odds with every day of his life?” Because if you can find a strong conflict within a character, you’re 90% of the way to creating a complex character. So with Richie, I was hoping to see him battling the fact that he screws singers over every day. He signs them to contracts he knows they’ll never make a penny for, and reaps the profits for his company. And it seemed to be heading in that direction with the Lester subplot, but it never quite got there.

Genre: Crime/Comedy

Premise: When the female TV star for a popular children’s show commits suicide, two low-life investigators are hired to look into claims that a dead-ringer for the actress has been seen around town.

About: One of the biggest specs out there right now, “The Nice Guys” has actually been around for over a decade, originally written in 2003. But the project has been jolted back to life, with both Russell Crowe and Ryan Gosling preliminarily attached. Shane Black (Lethal Weapon, Iron Man 3) co-wrote the script with Anthony Bagarozzi, who, despite this script being a decade old, is just now seeing his career blow up. He has four projects in various stages of development as a writer or director, including Doc Savage. Important to note: the script I’m reviewing today is the original draft written back in 2003.

Writers: Anthony Bagarozzi & Shane Black

Details: 135 pages (April 14, 2003)

Isn’t Hollywood great? No matter how deep into obscurity you sink, the town will always give you another chance. Shane Black was on one of the biggest screenwriting streaks in history in the 90s, selling every spec that spat out of his printer for a minimum of 1.3 trillion dollars. But then the printer carton burst on stylistic over-the-top dialogue-heavy specs and, Black found himself no longer able to heat his apartment with a fire full of hundred dollar bills.

Oh sure, Black probably got plenty of money in those “lean years” doing rewrites. But once you’ve tasted the frosting at the top of Hollywood’s cake, you never want to go back to the frozen Sara Lee stuff again. So Black did something smart. Instead of waiting for Hollywood to re-recognize his genius again, he directed his own script, Kiss Kiss Bang Bang. And for a brief moment, Black was back.

The flick didn’t make enough money to catapult him back to the top but it just so happened to get him a strong relationship with Robert Downey Jr., who became a super star when he starred in the surprise hit, Iron Man, a few years later.

Fast forward another few years, and guess who was now calling to ask Shane to direct the newest entry in the franchise?

What’s funny about all this is that a script Black wrote all the way back in 2003, which he couldn’t get the local community theater director to read, was now the hottest script in town. Does Black’s return celebrity make this script better than it once was? Or was the script overlooked in the first place? Let’s find out.

Suzy Shoemaker is the adorable 20-something star of one of those kids shows that every 4 year old in the universe loves. She’s also dead. Or, she kills herself at the beginning of the movie after a private sex tape surfaces of her.

Cut to Jackson Healy, a “private enforcer” of sorts, the adult version of a bully-for-hire, who thin-timidates anybody who messes with you, for the right price of course.

If Healy’s low-rent, Holland March is a 20 dollar a month storage unit. The 40-something private investigator makes most of his money by taking advantage of the Alzheimer’s crowd. Say a mentally absent old woman needs to find her husband (who’s, of course, dead). Holland has no problem taking the dough and “looking for him.”

These two winners are forced to team up and find “Alice,” a mysterious lookalike for the dead Suzy Shoemaker, and a semi-professional porn actress. Is it a coincidence that Suzy killed herself over a porn tape when there’s someone who looks exactly like her that does porn? That’s what these two need to find out.

Oh, and Suzy Shoemaker also happens to be the daughter of presidential hopeful David Shoemaker. All of a sudden, these suspicion crumbs are starting to look like they may belong to a freshly baked conspiracy scone.

To throw just one more wrench into this equation, March’s 14 year old overly-inquisitive daughter, Holly, wants to help. March knows this is a bad idea, but there are so many hip young folks involved in this mystery, that having a teenager around to do some undercover snooping may end up paying off.

Of course, you know if a 14 year old girl is getting involved in a case with dead people, that at some point said 14 year old girl is going to be in danger. So March and Healy aren’t just going to have to solve this case. They’re going to have to keep Holly safe, something that becomes harder and harder to do the deeper this mystery gets. And in case you’re wondering, it gets real deep!

Black (along with co-writer Bagarozzi) does what he does best. He puts a couple of flawed ill-matched individuals on a case together and allows them to equal-parts succeed and stumble their way to success. It’s what made Black one of the most successful screenplay writers ever.

But as we all know, this is one well-worn genre. The audience has seen it all. Therefore, if you want to succeed, you have to do more than follow a formula. And The Nice Guys separates itself from its competition in a couple of ways.

First off, this is Shane Black. He’s so fucking good at writing this kind of movie, that he stands out from everyone else just by showing up. Everything from the action to the dialogue is a level above. It’s funnier. It’s smarter. It’s better. Every other page we get a line like, “Marriage is buying a house for someone you hate.” Or, “If you had me ‘figured,’ jagoff, you’d start running – and you wouldn’t stop ‘til all the signs were in Spanish.”

Then there were the descriptions: “The Counter Girl is a punkish looking freak with pierced everything.”

We even get fun little moments that your average writer never thinks of. For example, you ever wonder where those stray bullets go? In a scene where Healy’s struggling to get away from the bad guys, he barely avoids a shot to the head. Instead of that being the end of it, we watch the bullet go out the window, across the street, and strike an unsuspecting woman at her window in the shoulder. She yelps and falls down out of frame. It was hilarious.

But just being the best at a genre isn’t enough. You should always be pushing yourself, looking for little angles to make your story different from any other “buddy cop” flick out there. Here, Black and Bagarozzi do this with Holly, March’s 14 year old daughter. I mean how many buddy cop movies have you seen where the cops are forced to lug a 14 year old girl around? Not many.

And it’s not just for show. You see, when you add an unknown element to a known situation, you get a new dynamic. Your cop duo can’t just hurl predictable insults at each other for 90 minutes. Healy has to be careful with what he says, since Holly’s always around. March has to stop every once in awhile and figure out how to keep Holly out of harm’s way.

There are even situations where March needs his daughter to get the job done (fitting in with a younger crowd to infiltrate a party). So his daughter temporarily becomes the most valuable commodity of the three, giving her the power, and shifting the dynamic, once again, to something that feels unfamiliar. Which is good! The last thing you want in a buddy-cop movie is brain-numbing familiarity.

Here’s the thing with The Nice Guys, though. It has a lot of moving parts. It’s basically like “The Other Guys,” but with a brain. And while that’s certainly nice (yay for movies that don’t pander!), it feels like it needs a simplicity pass. I couldn’t figure out, for the life of me, why Suzy Shoemaker’s aunt hired March to find Alice (the Suzy lookalike) in the first place. Did she think Alice was her niece? Did she just want to see a woman who looked like her niece? I don’t know.

And I know that information is in the script somewhere. But I had to process so much information, it slipped by me. This happens a lot. I’ll confusedly ask a writer, “Why did Ace want to double-cross Mary if he was in love with her?” And the writer, huffing and puffing, will animatedly respond with, “Did you even read the script!? The answer is on page 55 line 12. She gives him the copy of The Grapes of Wrath, which, if you remember, he read to her on page 12 in their childhood flashback, and she said, if you ever see this book again, it means I can never be with you.” Um, right.

The point is, the more complicated a plot is, the more hand-holding the reader needs. ESPECIALLY in the early-going, since that’s when the most new information is being thrown at the reader. Later, when we have all the names and relationships down, we can handle those details. But early on, it can be tough. So we need your help.

The only other issue I had is that it didn’t feel like there was enough conflict between Healy and March. This is always a sticky issue when you write a buddy-cop flick because, on the one hand, you don’t want to write another clichéd: two “cops” hate each other for no other reason than it leads to lots of conflict-fueled arguments!

But if you go away from this cliché, you run the risk of the relationship being bland. I mean sure, you can claim, “I didn’t do the cliché thing! Points for me!” But was it really worth it if we’re now bored by an uninspired relationship? I still haven’t figured out this balance. How does one write a genre where the very core rules of the genre are cliche, and then not make it cliche (I’d love to hear thoughts on this in the comments)?

Indeed, I felt like there was something left on the table between Healy and March. While they were definitely different characters, the longer the script went on, the more similar they felt. Maybe that’s because Black and Bagarozzi were looking to avoid the “clashing personalities” cliché. Maybe not. I don’t know. But I hope in subsequent drafts, they address it.

Anyway, regardless of its issues, The Nice Guys was a fun little script. Definitely worth reading. I mean, how can you say no to the newest/oldest Shane Black joint?

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Dialogue set ups and payoffs. Shane Black loves setups and payoffs. But he doesn’t only do it with his action. He’ll use the device in dialogue as well. This is a great way to get an easy laugh. For example, when March is forced to take Holly to a party to help them find Alice, they first walk in and see a bunch of sketchy characters. “Dad, there’s like, whores here and stuff.” March responds with, “Holly, how many times have I told you..? Don’t say, “and stuff.” Just say, “There are whores here.” Later on, Holly finds herself in a room watching porn with an overtly sexual redhead. Holly, working for her dad, casually asks the redhead if she’s seen Alice. “What’d she look like?” the redhead replies. “Well,” Holly says, “Sorta like that woman on TV, that kid’s show chick who died—“ “The one who just offed herself? That’s rad! She’s all, “remember kids, politeness counts,” meanwhile she’s like, doing anal and stuff.” Holly capitalizes on this: “Don’t say, “and stuff” – just say, “She’s doing anal.”

What I learned 2: What I’m about to tell you may be the most important advice you ever hear. Like, EVER, and stuff. I’m serious. Tape this to your wall. Tattoo it on your forehead. Ready? Never wait for this town (or for that matter, the world) to give you anything. If you want something, you will never have it unless you GO OUT AND GET IT. Black was in a downward slope in his career. If he would’ve kept writing scripts in his multi-million dollar basement, hoping for success again, I’m not sure we’d be hearing Black’s name today. Instead, he went out and MADE A MOVIE HIMSELF, which led to a relationship that would later turn him into one of the hottest directors in town. If I say it once, I’ll say it a thousand times: NEVER WAIT FOR ANYTHING. GO OUT AND GET IT.

Get Your Script Reviewed On Scriptshadow!: To submit your script for an Amateur Review, send in a PDF of your script, along with the title, genre, logline, and finally, something interesting about yourself and/or your script that you’d like us to post along with the script if reviewed. Use my submission address please: Carsonreeves3@gmail.com. Remember that your script will be posted. If you’re nervous about the effects of a bad review, feel free to use an alias name and/or title. It’s a good idea to resubmit every couple of weeks so your submission stays near the top.

Genre (from writers) Historical Action

Premise (from writers): In 30 A.D., a charismatic stonemason bent on revenge leads a band of guerrilla rebels against the Roman occupation of his homeland.

Why You Should Read (from writers): This is the story that led up to the biggest trade in human record. It is Braveheart meets Gladiator, with characters on a collision course that splits history in two. Come for the battle, the intrigue, and the epic. Stay for the sacrifice, the betrayals, and the passion that drives a man to darkness. — As co-writers, we work from 3,000 miles apart. Yes, we have two of the WASPiest names imaginable. No, they’re not pen names. We’ve been polishing this script to a trim, accelerative tale that strengthens, weaves, and deepens with each choice our characters make. The ending is the most difficult we’ve ever worked on, but the feedback on the resolution has been powerful. We have to earn the effect we want a story to have, and with this script we aim to challenge, to provoke, but most of all…to entertain.

Writers: Parker Jamison & Paul Kimball

Details: 112 pages

Man, the last couple of days have been carraaaa-zy in the comments section. The Comments Post did not go over well with a lot of you. Miss Scriptshadow’s review caused a nuclear-sized meltdown in the Grendl-verse, and some manic derilect from 2011 topped it all off with a bunch of “Carson is evil” comments.

Today, however, it’s going to be all about the script. If you want to talk about other things, feel free to go back to those earlier posts. But I want today to be about the writing, specifically Barabbas. I’ve already read Barabbas once for a consult and I liked it with reservations. So I’m really glad you guys picked it as a healthy discussion should continue to strengthen the script even more.

The story is not without its challenges. It puts itself in some unenviable writing situations, which I’ll get to after the summary. I’m also interested to see what these guys have done with the latest draft and how much the script has improved. Let’s take a look.

“Barabbas” offers something whether you’re familiar with the story of the man or not. If you’re like me and had never heard of him, Barabbas plays out like a slow-burning quasi-mystery, pulling in familiar elements from religious history that eventually lead to a shocking finale.

If you do know Barabbas’s name, the script plays out like “Titanic.” You know where this will eventually end up, so you’re curious what’s going to happen to get us there.

Joshua Barabbas, 30, is a stone mason. Along with his younger brother David, the two build bridges and aqueducts for the Romans who, at the time, were occupying Jerusalem. When the Romans raid the Jews’ own temple to pay them their wages, David and Joshua have had enough, and rebel.

When their friend is erroneously chosen as the instigator of this rebellion and crucified, an angry Barabbas is persuaded by a local politician, the sinister Melech, to start a war. Using rage to guide his leadership, Barabbas and his fellow workers attack the Romans, but eventually flee to the mountains once outnumbered.

Realizing that there’s no turning back, Barabbas starts to grow a small army with the hopes of driving the Romans out of Jerusalem. But when Barabbas falls for the wife of a key ally in the city, he loses focus, and the rebellion begins to fall apart.

In a last ditch effort to recruit a huge army from the surrounding regions, Barabbas designs a plan to take down the Roman Regional Governor Pontius Pilate. (major spoilers) He ultimately fails, and his life hangs in the balance of the people themselves, when they must choose which of two men shall be set free, Barabbas or Jesus Christ.

I knew this weekend’s Amateur Offerings was going to be good because I’d read two of the scripts and knew both were solid (the other being “Reeds in Winter” about the infamous Donner Party, which ended up in some gnarly cannibalism). The rub? They were both period pieces, which are the hardest to get readers on board with. Therefore it was satisfying to see them both end up with the most votes, as it shows that readers still respect challenging material.

With that said, each script has its trouble spots. Assuming the reader sticks around long enough to get into the story, which is never a guarantee with period pieces, I was always worried about that darned Barabbas second act.

The problem is this – the second act is where countless scripts go to die. It’s hard as hell to keep it interesting even under the best of circumstances. In Barabbas’s second act, our army is relegated to a single location up in the mountains. Keeping a “swords and sandals” period piece lively when the main character and his army are relegated to one spot for 60 pages is as challenging a proposition as you’re going to find in screenwriting.

Compare that to Braveheart. The great thing about that film was that William Wallace kept moving across the country to bigger and bigger cities, so we got this sense of BUILDING as the story went on. That’s harder to do when characters are hiding in caves in the mountains, especially when you’re limited by history. Barabbas’s army couldn’t have gotten TOO big or else he would’ve been more well known in the history books. Barabbas’s one defining characteristic in the bible is that so little is known about him.

But my gut’s telling me we need to either get Barabbas off that mountain space at some point, grow his army bigger in some way, or find some other means to spice up the second act.

What if, for example, Barabbas had to go out on some recruiting trips into the surrounding cities? If we built up certain meetings with city leaders he would have to win over in order to receive their soldiers, that’d be one way to keep the story dynamic.

Getting him off the mountain to meet Jesus at some point would be interesting as well, but Parker told me he doesn’t want to physically see Jesus until that final scene, which I understand.

Another thing that bothered me during the initial read, and something I don’t think Parker and Paul have addressed yet, is the character of David, Joshua’s brother. Over the course of the script, David sees Jesus speak (we don’t see this) and starts to respond to his teachings. Whereas Barabbas wants war, David preaches forgiveness and peace.

The problem is that all of this happens too late and doesn’t have enough conviction. I was bothered, for instance, by a character named Thaddeus, who comes into the story late to aggressively preach Jesus’s philosophy. I couldn’t understand why this character wasn’t David. In order to get the maximum amount of conflict from a relationship, you need the two characters to be on opposite sides of the philosophical spectrum. David was tepid in his support of Jesus’s teachings until the very end. Let’s have this guy go out there, see Jesus speak, and let him be the one who comes back and starts aggressively converting the other soldiers. Now you have a direct conflict. Barabbas needs soldiers to take down Pontius and his own brother is turning those soldiers into pacifists. Isn’t that better than Random Thaddeus, who I met five minutes ago, who has no allegiance to anyone, converting these people?

One of the complaints about Barabbas during AOW week was dialogue. Most people said it was serviceable, but that serviceable isn’t good enough in a spec trying to stand out. And I’d agree with that. But fixing this is a lot easier said than done.

What I believe people are responding to here is the lack of “fun” in the dialogue. People always seemed to speak in a proper and serious way. “You still labor at the aqueduct?” “Every day. Why?” “I’ve heard that funds are running short. That Pontius Pilate needs extra coin to finish it.” “As long as the Romans pay, we work.” This is a conversation between two people who have secretly loved each other since childhood. You’d think they’d have a more relaxed and easy rapport, right?

But the biggest issue here is that almost EVERYBODY spoke like this or very similar to this. So the problem might not be “dialogue” so much as “variety in dialogue.” I always talk about creating “dialogue-friendly” characters. People who have fun with the language and say things others wouldn’t. It would be nice if a featured character here were dialogue-friendly. From there, look at every character and figure out ways to make them speak differently from everyone else.

Finally, I wanted more out of the ending. I think the problem here is that Parker and Paul see the sacrifice at the end as the climax. Which it is. But before we get there, we need to give the audience the climax they’ve been waiting for, the one we’ve been building up for 80 pages, which is an attack on Pontius Pilate.

Let’s see him and his army try to head Pontius off at the pass on his way to Jerusalem. Let’s see him almost kill Pontius. He ALMOST does it! But something at the last seconds prevents him from succeeding and he’s captured.

Then, since it’s now personal between him and Pontius, we can see Pontius, behind-the-scenes, preparing Barabbas so that he’ll be the one picked for crucifixion by the people. Pontius makes him extra dirty and nasty looking, in the hopes that he’ll be the one killed.

I know we’re playing with fire here, but it could be an ironically delightful ending to see that Pontius had a horse in the race and was hoping to snuff out Barabbas, which, of course, would’ve changed history. He’s visibly disappointed, then, when Jesus is chosen instead.

Whatever these guys choose to do, though, I trust them. Barabbas is not perfect, but it shows a lot of skill, and it shows two writers who are going to make a splash at some point if they stick with it. I don’t know if it’s going to be with this script because, again, the subject matter is challenging, it’s a unique sell, and there’s that whole second act issue that I’m not convinced is solvable. But I just like these guys as writers and hope to see more work from them in the future.

Script link: Barabbas

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Use specificity instead of generalizations when writing description. Today’s “What I learned” actually comes from Casper Chris, who I thought made a GREAT observation when he compared two action paragraphs from Barabbas and Braveheart during AOW. Here were the two he compared…

Barabbas:

Barabbas leads the charge. The rest of the stonemasons pour down on the patrol. Slashing, spearing, hacking. Barabbas fights like a barbarian, fearsome and brutal. Ammon slices through soldiers with precision. David is quick and athletic.

Braveheart:

He dodges obstacles in the narrow streets — chickens, carts, barrels. Soldiers pop up; the first he gallops straight over; the next he whacks forehand, like a polo player; the next chops down on his left side; every time he swings the broadsword, a man dies.

Notice the difference. Whereas the Barabbas text uses mostly general words to describe the action (“slashing, spearing, hacking” “fights like a barbarian” “quick and athletic”), Braveheart uses specific imagery. There are more nouns here and the verbs are used to highlight powerful actions (“chickens, carts, barrels” “soldiers pop up” “he gallops straight over”). It was a great reminder that we need to put specific imagery into the reader’s head so he can properly imagine what’s happening up on the screen.

Tarantino’s writing probably contains more exceptional elements than any other writer in the business.

Tarantino’s writing probably contains more exceptional elements than any other writer in the business.

The worst scripts in the world? They aren’t the worst scripts in the world. There are scripts even worse.

Make sense? Probably not. But it will be by the end of this article.

Consider yourselves lucky. Here at Scriptshadow, we don’t let you see the bad stuff. The scripts you see on Amateur Offerings every week? Those writers have at least demonstrated an understanding of the craft. But the truly bad ones? Those don’t make it in front of your eyes. For that reason, you don’t know what it’s like to read something truly bad.

I remember a couple of years ago, I read this script where I had ZERO understanding of what was going on. This writer had the ability to write pages and pages of story where nothing actually happened, so I’d find myself having read 10 pages, but not being able to remember anything that transpired. If you put a gun to my head, I’d probably tell you it was about a goddess trying to blow up a volcano. But if the writer had told me it was about a Christmas tree who fell in love with a menorah, I wouldn’t have argued. It was that vague.

But look, the truth is, these “really bad” scripts are often the result of new writers who haven’t studied the craft and who have never gotten feedback. They write down exactly what’s in their head as they’re thinking it, believing it will make sense to us because it makes sense to them, not realizing that writing a screenplay requires a stricter kind of logic that takes some trial and error getting used to.

So to me, those aren’t the worst screenplays. The worst screenplays are the AVERAGE SCREENPLAYS.

There’s no emptier feeling I get than when I read an average screenplay. I mean, at least with a really bad script, you remember it. With an average script, it’s forgotten as soon as you put it down. It goes through you like fast food. And the sad thing is, I’ve been reading 15 of these scripts a month. It feels like this huge collective of screenwriters has accepted mediocrity. So when I see the spec market starving, it doesn’t surprise me. Who’s opening up their checkbook for another average script?

Let me give you an example. I once read a buddy-cop script (I had to go back to it to re-familiarize myself) that had the two cops who hated each other, it had the standard “witty” back-and-forth banter, it had the familiar drug plot, it had the cop who was secretly one of the bad guys. This is the exact dialogue going on in my head as I read it (“Seen that before. Seen that before. Seen that before. Seen that before.”). I must’ve said that to myself 80 times. There wasn’t a single elevated element in the story.

I don’t know what writers expect after writing these scripts. Do they think they should be praised because they successfully gave us an average version of something we’ve already seen before?

With a script, you have to stand out somehow. A series of average elements isn’t going to cut it. Readers want to see original takes on elevated material. Which brings us to the term of the day: Exceptional Elements.

An exceptional element is any element in your script that’s better than average. You’d like to have as many of these in your screenplay as possible. But realistically, you probably won’t get past 3. Which is fine, because that’s all you need to write something noticeable, and definitely all you need to write something better-than-average.

To add some context, there are three scripts I really liked over the last few weeks: Hot Air, Cake, and Tyrant. Let’s see what the exceptional elements were in each. With Hot Air, the dialogue (especially Lionel’s) was an exceptional element, the characters were an exceptional element, and the plotting was an exceptional element (I never quite knew where things were going next).

In Cake, the creation of a severely unlikable protagonist who we still ended up caring about was an exceptional element, the unusual premise was an exceptional element (haven’t seen that before) and the unique voice (the offbeat weird way the writer saw this world) was an exceptional element.

In Tyrant, the intricate nature of the relationships were an exceptional element, the lack of fear in pushing the boundaries was an exceptional moment (a few uncomfortable rape scenes, etc.) and the ending was an exceptional element (in that it revealed something shocking about our main character that we never would’ve guessed).

Before we get into specifics here, I want you to think about the screenplay you’re working on now. And I want you to take off your bullshit hat. Put your critics hat on, the guy who can tear down the latest blockbuster in a 300 word paragraph. That’s the guy we need judging your script. Now ask yourself, what are the exceptional elements in your script? What can you honestly say stands out from anything out there? Need some reference? Here are a dozen of the more popular screenplay elements to choose from. If you’re exceptional with just three of them, tell us in the comments section, cause we’re going to want to read your script.

Clever or unique Concept – One of the easiest ways to elevate your script is a great or unique concept. Dinosaurs being cloned to make a Dinosaur Theme Park (Jurassic Park). People who go inside other people’s heads (Being John Malkovich).

Unique or complicated characters – This is a biggie. If you’re going to have only one exceptional element, it should be this, because a script is often defined by its characters. Give us Jack Sparrow over Rick O’Connell (Brendan Frasier in The Mummy). Give us Jordan Belfort (The Wolf of Wall Street) over Sam Witwicky (Transformers).

Spinning a well-known idea – Taking ideas and spinning them is one of the easiest ways to stand out. Instead of that same-old same-old buddy cop script I talked about earlier? Make it two female cops instead (The Heat). Or set some ancient story in a different time (Count of Monte Cristo in the future – a script that sold last year). This is what’s known as a “fresh take,” and Hollywood loves fresh takes.

Take chances – How can you expect to be anything other than average if you don’t take chances? Playing it safe is the very definition of average. So you’ll have to roll the dice a few times and get out of your comfort zone. Seth McFarlane made a comedy about a grown man who was best friends with his childhood teddy bear. Nobody had ever written anything like that before. That’s rolling the dice.

Push boundaries – This will depend on the script. But if you’re writing in a genre that merits it, don’t play it safe. Push the boundaries. That’s what Seven did when it came out. We’d seen serial killer movies before. We’d never seen them with kills that were THAT sick, that intense.

Plotting – A deft plot that keeps its audience off balance (with mystery, surprises, dramatic irony, suspense, setups, payoffs, twists, reversals, drama, deft interweaving of subplots, etc.) can put you on Hollywood’s map. Hitchcock’s big exceptional element was his plotting.

A great ending – A masterful ending is a huge exceptional element because it’s the last thing the reader leaves with. If you can give them something immensely satisfying (The Shawshank Redemption) or shocking (The Sixth Sense) and it works? You’re golden.

Dialogue – One of the hardest elements to teach and the most dependent on talent. There are definitely ways to improve your dialogue, but usually people are either born with this element or they aren’t. Don’t fret if you aren’t though, because you still have all these other elements to choose from.

Imagination – If you’re writing fantasy or sci-fi, you better show us something we haven’t seen before. For example, if you’re going to put your characters in yet another mech suit (Matrix sequels, Avatar, Edge of Tomorrow), why should we trust you to give us an imaginative story? These are the genres that demand originality. So if you don’t have anything besides what you’ve seen in previous sci-fi movies, don’t play in this sandbox.

Voice – If you see the world in a different way from everyone else, it’s one of the easiest ways to stand out. This is all about the unique way you write and the unique way in which you observe the world. Having a truly original voice is almost the anti-average, because if someone can identify who you are by your script alone, it means you have a unique take on the world.

Scene writing – Are you an exceptional scene writer? Are you able to pull readers into every scene? Read Tarantino’s scenes like Jack Rabbit Slims or the Milk scene at the opening of Inglorious Basterds. Or watch the scene where the detective questions Norman Bates in Psycho. The level of suspense in these scenes is off the charts.

A great villain – Typically someone who’s complicated and not just evil for evil’s sake (which is the case in almost every average script I read). I still can’t get over The Governor in The Walking Dead. The way he fell in love with a woman and cared so deeply for her daughter, only to set up a plan to kill women and children a few scenes later.

In general, to avoid writing something average, you have to be your harshest critic. You have to be self-aware enough to call yourself on your bullshit. Look at every individual element in your screenplay and ask yourself, “Is this unique?” In some cases, it won’t be. That’s fine. As long as you have exceptional elements to offset the average ones. The Heat had an average plot. But by putting two women in the cop rolls instead of men, it gave the genre a fresh take. Exceptional element success.

The truth is, readers really want to love your script. But you’re preventing them from doing so when every element in your screenplay is something flat, derivative, uninspired, or rushed. Writing a great screenplay means doing the hard work, and that means not being satisfied with a bundle of average components. Average dialogue, average scene-construction, average concept, average imagination, average characters. We’ve already seen all these things so what do you gain by showing them to us again? Get in there and raise the quality of your script by infusing it with as many exceptional elements as you can. I’m rooting for you because the better you get at this, the more good scripts I get to read. Good luck!

We’re going to do something a little different in today’s article. We’re going to talk about the actual PRESENTATION of a screenplay. The way it’s written, the way it looks to a reader on the page. While not as important as story, the choices in how one presents his work can have a big influence on how the reader interprets it. The theme you’ll find here is that while some approaches are preferable to others, every writing choice you make should be made for one reason: it’s the best way to tell the story at that particular moment. With that said, here are some common issues I run into when I read scripts.

CLIPPED WRITING

Clipped writing is something I see a fair amount of. The idea behind this is that traditional writing is too long-winded for screenplays, which require a more “to the point” approach. The problem is, some people have taken this so far that it’s unclear what’s being said. After awhile, the reader starts to feel like they’re reading an illiterate robot. For that reason, this style probably shouldn’t be used outside of special situations. Maybe, for example, a character wakes up at the beginning of the script and is confused. So the confused stutter-pattern of clipped writing helps convey the character’s confusion. There are also times when it works in action sequences. But for the most part, try to write full sentences.

BOLDED SLUGS (or BOLDED UNDERLINED SLUGS)

Bolded slugs (or bolded underline slugs) have become in fashion lately. And to a certain extent, they make sense, as they visually signify a new location or scene, which can be helpful to the reader. Where bolded slugs get annoying is when there are a lot of short scenes or the writer is a slug-lover, so that four times a page, we’re stuck staring at big chunky ugly disruptive lines of text. My suggestion would be this. If you write a lot of long scenes, like, say, Tarantino, you can use bolded slugs. But if you’re constantly jumping from one place to the next, step away from the bold. It’ll shift the reader’s attention away from what really matters, which is the action and the dialogue.

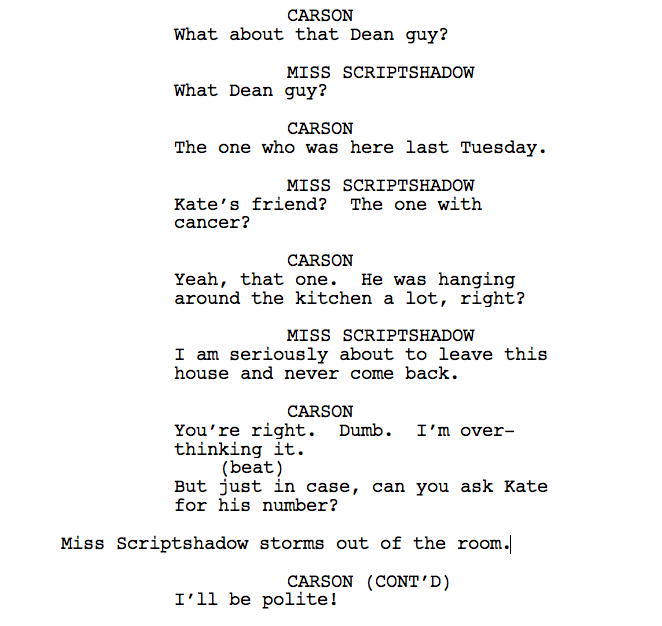

THE ‘GET INSIDE THE CHARACTER’S HEAD’ ACTION LINE

Using your description to tell us what a character is thinking is considered shoddy writing. However, I do see it quite a bit (there was a decent amount of it in “The Fault In Our Stars.”). Where it becomes problematic is when a writer gets carried away with it and starts using it for things we already know. As you can see above, we can tell from the dialogue that Miss Scriptshadow doesn’t want to see X-Men, so using description to tell the reader afterwards feels like overkill. If you want to make sure the reader gets the point, there are other options, like using an action. So you might cut to Miss Scriptshadow’s computer, see that she’s looking at a trailer for “The Other Woman,” longingly, then click it closed with a sigh. I’m telling you: Only use this device sparingly. It can get annoying quickly.

LOVE OF ADVERBS

Forget the dialogue here. Look at the action text. Carson “walks aggressively.” He “angrily opens it.” Adverbs make your writing look weak and indecisive. Instead, try to find a verb that says the same thing. You’ll notice that your sentence all of a sudden looks manly and strong! “Carson barges towards the fridge.” “He whips it open.” Just make sure that you have the right verb for the action. Don’t put in a verb that doesn’t fit just to avoid the adverb. In other words, don’t say Carson “dances over to the fridge” just because I said you had to verb it.

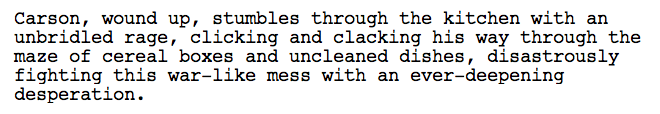

SIMPLIFY YOUR WRITING WHENEVER POSSIBLE

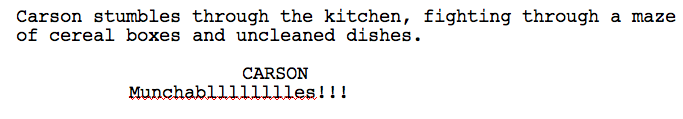

Readers don’t want to have to work for basic information. Screenwriting should be simple and to the point (most novelists will actually tell you the same thing). The above is a really clunky sentence, the kind a man could get lost in and never come back. If I had to read a whole script of that, I’d swallow a box of brads and die by internal bleeding first. To simplify this, focus on two things. First, figure out how to turn useless segments into actions, then figure out what’s redundant or isn’t needed. For example, there’s no need to say “wound up,” since we already know he’s wound up and it interrupts the flow of the sentence anyway. So we’ll drop that. “Clicking and clacking” does add some sound to the scene, but I’m not sure it’s necessary. “Disastrously fighting this war-like mess with an ever-deepening desperation” is redundant. If we really want to convey Carson’s anger, we can add an action, like him shouting in frustration at the end. So the new simpler text would look like this:

I’m not saying you should NEVER offer detail in your writing. You just only do it when it’s important. Like if a detective walks into a crime scene where very specific things will be important to know later on – then go for it – describe away. But a guy looking for munchables? We don’t need to get into any detail with that, unless you’ve got some amazing jokes you can weave into his search (even then, it’s probably not worth it – simplicity should usually win out).

SUBSEQUENT ACTION LINES (NO SPACES IN BETWEEN)

While I can’t speak for everybody, this practice drives me CRAAAA-ZY. I don’t know who came up with it, but the sooner it goes away, the better. First of all, you want to be weary of any writing device that goes against what readers are used to unless you’re positive it makes the script better. The above looks so odd to a reader, they’ll probably stop for a second and wonder if it’s a formatting error before moving on. I’m not even sure of this device’s intention. I just know that it looks and feels odd.

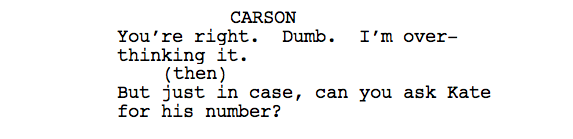

THE BEAT SHOULD NOT GO ON

There was a time and place for “beat” when the screenplay was a technical blueprint. But these days, it’s more about making the screenplay readable. Anything that breaks the suspension of disbelief is our enemy. So when you say “beat,” what does that mean? It means fake-ish artificial term that has no organic reason to be in your story. Whenever you can, replace “beat” with something more natural so as not to draw attention to its technical-ness. For example, I’d probably write this instead…

THE DREADED ‘WALL OF TEXT’

Okay, this above scene is kind of funny, but that’s not what we’re looking at. When a reader turns the page, they immediately see a general snapshot of said page. The last thing they want to see during this moment is a “WALL OF TEXT.” At least three paragraphs with five lines or more. At least one character who talks forever (or two characters who exchange 6-7 line chunks of dialogue each time they speak). There’s no doubt that there will be times in your script where you’ll need to write a lot. Characters do occasionally have monologues (even those should be rare though).

But if there are a lot of pages that look like this? With big huge paragraphs and character exchanges where both characters are taking forever to say shit? The reader has given up on you. The correct way to write is to rarely go over 3 lines per paragraph, and your characters shouldn’t exchange more than 2-3 lines at a time (this will differ depending on character and scene, but it’s an average to keep in mind). Also, it should be noted that the WORST place this can happen is on your first page. I see a LOT of amateur writers open with that wall of text and I just know the script is going to be bad. :(

IN SUMMARY

A good reader – and I’m talking about the reader who you’ll eventually have to get past to sell your script – takes his reading job just as seriously as you take your writing job. So he’s going to have his set of reading quirks, things he can’t stand. The last thing you want is to trigger any of those annoyances, because then the reader is judging you on something other than what they should be – the story. Like that wall of text. Again, when I see that, I know it’s over. I know it’s over right away. Sure, there are like 2 exceptions in the last 10 years of scripts overcoming this, but for the most part, readers know it’s a disaster. Just remember that your job is to make things as easy as humanly possible for the reader. You want their read to be effortless. So don’t do anything weird or annoying unless you’re absolutely sure it makes the reading experience and your story better.

What about you guys? What are some things that drive you nuts when you read?