Search Results for: F word

Genre: Romantic Comedy

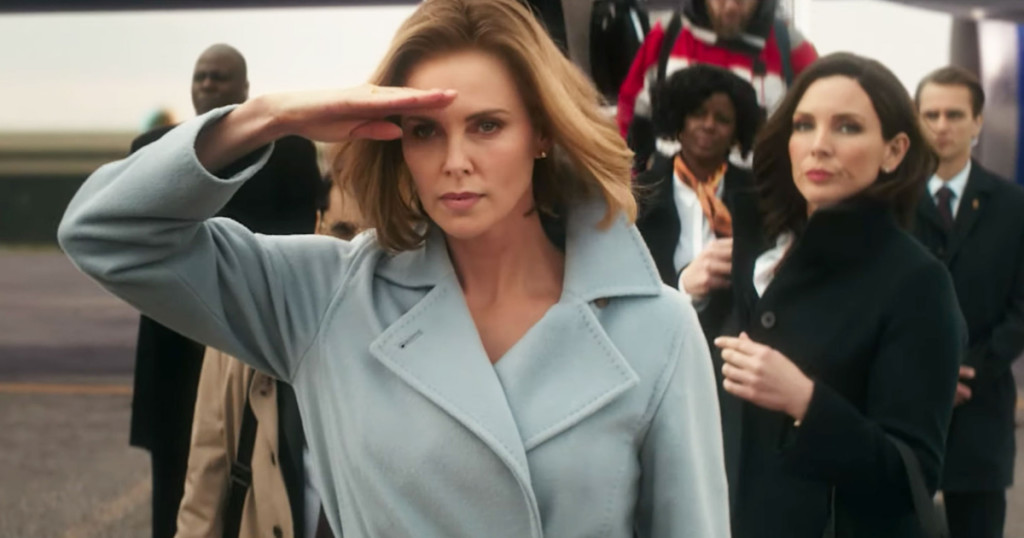

Premise: A schlubby political writer is scooped up by the Secretary Of State to help write speeches for her presidential run.

About: This script made the Black List – count with me now – EIGHT years ago. Never say die in this business, right? Dan Sterling, the script’s original writer, has written on The Office, King of the Hill, and South Park. Liz Hannah (The Post) came in to, presumably, add some authenticity and believability to Charlotte’s character. And then, of course, Seth Rogen’s uncredited gang of punch-up writers came in to add a lot of jokes, which I’ll be discussing in the review. Jonathan Levine, who’s worked with Rogen before on 50/50, directed the film.

Writer: Dan Sterling and Liz Hannah

Details: 2 hours long

Before we get started, can we all take a second to appreciate how hard it is to make a good comedy? I mean, how many truly funny comedies have there been since the beginning of the century? Five maybe? If that? That’s one every four years. I came into this screenwriting adventure thinking comedy was the easiest genre. I now believe it to be the hardest.

The Long Shot took that handicap, shoved all its chips in, and said, “I’ll raise you another handicap.” They added politics to the mix. Yeah, because politics in 2019 isn’t polarizing at all. I actually think The Long Shot did a pretty good job handling its political plotline. But here’s the final word on The Long Shot. The movie is a couple of inches shy of being really good. And, unfortunately, those couple of inches are the difference between a comedy blowing up and fading away. I mean it was RIGHT THERE. What happened?

Charlotte is the Secretary of State and one of the top Democrat hopefuls to take the office of the presidency in 2024. But when the current president, unexpectedly, decides he’s not running for re-election, Charlotte decides to take a shot (a long shot) at being the U.S.’s first female president in 2020.

There’s a small problem. Charlotte’s numbers show that she’s not funny. She needs someone to help punch up her speeches with some humor. Enter Fred Flarsky, a dopey glorified blogger who writes scathing articles on big business. While these articles are a bit… aggressive, they’re also funny. And here’s the thing – Charlotte actually knows Flarsky. She babysat for him when he was a kid. So when the two bump into each other at a fund-raising event, it’s a natural fit.

Charlotte’s team hates Flarsky. He looks like one of those old multi-colored umbrellas wrapped around a potato. And outside of his writing, he’s kinda clueless. But Charlotte likes him. And as the two work together on her big environmental pitch, a romance blossoms. There’s only one problem. Everyone knows that the optics of this perfect specimen of a human being known as Charlotte being with Flarsky aren’t ideal. Which means, sadly, their relationship is doomed.

This movie does so much right! We’ve got a super-clear high-stakes goal driving the plot – Charlotte’s bid for presidency. We’ve got two characters who we want to be together but have several levels of conflict getting in the way. We’ve got lots of great dialogue. All of the characters except for a few minor exceptions are funny. O’Shea Jackson Jr. is a movie star in the making. What I could do with just an ounce of his charm. And on top of that, all of the romance works, which is the hardest part in these movies! Theron and Rogen, surprisingly, have amazing chemistry.

And like I said, it makes for a good movie.

But then why isn’t it a GREAT movie? What’s holding it back?

For starters, Rogen’s joke people need to step the f*&% off. For crying out loud. You had a good script as is. Then Rogen’s people came in and added 50+ s&*%, p&*%, vomit, b*&^er, and bodily fluid jokes. I mean, seriously? I get it if you’re making Pineapple Express, The Extended Edition. But this is a political romantic comedy. Why is there a scene where Charlize Theron explains that she once had to s&%* in her purse during a meeting? Why is the CLIMAX of the movie, no pun intended, Seth Rogen jacking off into his own face? Seriously? That’s how you’re going to end your movie?

And here’s the real problem. When they test these jokes on audiences, people WILL LAUGH. That’s because they’re obligatory laugh jokes. People laugh at the outrageousness of them even though they don’t actually find them funny. However, Rogen’s team can point out that people DID laugh and therefore the jokes should stay. Again, I have no issues with this humor when it’s appropriate. A bodily fluid joke makes sense in a movie like The 40 Year Old Virgin, which is about a man who’s never used his bodily fluids. It makes zero sense here. This should’ve been a sweet political romantic comedy. Instead, they raunchified it, confusing the tone.

Then we had seemingly small miscues that had much bigger ramifications than the filmmakers realized. One of the major plot machinations was that Charlotte’s “humor” number was down. That was the only thing out of all of her traits the public didn’t like. But here’s the weird thing. The number was still high. She had, like, an 89 out of 100. It just wasn’t *as high* as the other numbers. The reason this is a big deal is because the ENTIRE MOVIE is built on her needing a comedy writer to make her funnier! So why are they giving her a B+ level of humor?? In comedy movies, you work with extremes. Subtle doesn’t fly. Make her comedy number a 65 so that SHE ACTUALLY NEEDS HELP. Otherwise, there’s no need to have Flarsky in the movie.

Sadly, we have yet another case of over-development. I get that this script was ten years old. But the only thing you should’ve had to update was the political stuff. They shouldn’t have messed with everything else and they ESPECIALLY shouldn’t have stuffed in a bunch of lowest common denominator jokes. These guys are comedy veterans. They should know by now that different comedies require different types of humor.

I have one last thought. I remember there was this old belief, when movie stars didn’t do TV, that went something like this: “Why would they pay for you at a theater if they can get you at home for free?” It sounded good but there wasn’t any real way to prove or disprove the hypothesis since there weren’t enough people crossing over to a study on. But then the Franchinizing happened, and movie stars were forced into television. And I think I can finally say that when there aren’t any special effects or big concepts in a movie – when the film is just about the actors, as is the case with The Long Shot – it doesn’t feel special anymore. You’re sitting there watching the movie and saying, “Was this really worth 20 bucks?” The answer, unfortunately, is no.

But I have a feeling this is going to become a huge hit on digital. Had it debuted on Netflix, it would’ve been their best romantic comedy ever, and probably would’ve gotten a lot more fanfare. It’s a good movie. It really is. It just never gets over that “great” hump.

[ ] What the hell did I just watch?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the stream (when it comes to digital)

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: I’m going to steal from myself and use my original Flarsky ‘what I learned’ tip – “The impossible choice. Force one of your leads into an impossible choice at the end of the movie. Here, Charlotte must choose between her career and Flarsky. If you set that decision up well (where each choice has devastating consequences), we’ll be dying to know what they choose.” I’d add to this that when you’re writing a character piece, the “impossible choice” is really the only way to end your movie. You don’t have a big action set piece to do the heavy lifting. It’s all character. And there’s nothing more compelling than one of your characters being forced to decide between two things that they desperately want.

Genre: Thriller

Premise: A highly publicized AMA session with an aging musician goes off the rails when a hacker starts revealing dark secrets from his past.

About: This script finished in the top 10 of last year’s Hit List. The writer, John Wikstrom, is a Florida State grad who has a couple of short films under his belt. Wikstrom is repped by one of the last big spec agents in Hollywood, David Boxerbaum.

Writer: John Wikstrom

Details: 105 pages

Praise the LOOOORRRD! A non-biopic. I feel like throwing a party.

One of the hardest things to do in screenwriting is to find an idea that nobody’s come up with yet. But doing so is not impossible. In fact, a quick way to circumvent the issue is to choose a subject that’s only recently been added to the public lexicon.

While AMAs aren’t rolled-off-the-assembly-line-yesterday new, they’re new to most people. And that makes them potential fodder for a movie. But can someone build an entire narrative around people asking questions? Let’s find out.

Margo is that rare Los Angeles publicist who’s actually sweet. That wholesome quality has made her popular with artists, and that popularity results in the Johnny Cash-esque David Dollar requesting that Margo personally direct his AMA (“Ask Me Anything”) on Reddit, where he’s promoting yet another greatest hits album.

Margo heads over to Davey’s enormous mansion in the hills and is immediately charmed by the 70 year old legend in spite of herself. Davey seems amused by this thing they’re doing. This is a man who came up in the old school era where you remained elusive and mysterious. Nowadays artists are sharing their latest bowel movement on Instagram. It’s all a bit confusing for an old man.

Margo tells him not to worry. She’ll take the reins. She’ll read off the most upvoted questions, he’ll answer them, and she’ll type. An hour of painless fun. And it is painless for awhile. Until a mystery user posts a picture of Davey’s old girlfriend, Elizabeth Kelly, with a black eye, and asks the question, “Did you beat her?” Margo tells Davey he doesn’t have to answer but he insists he has nothing to hide, and explains that Elizabeth was actually hurting herself back then, which was well documented.

The AMA gets back on track but then things get real. Someone posts all of Davey’s financial records as well as his entire e-mail inbox. And just as Margo prepares to end the AMA, a naked picture of her is posted. She gets a direct message informing her that there are more where that came from if she stops this AMA. They have no choice but to keep going.

Surprisingly, every accusation that the reddit users are able to dig up from Davey’s private files, he has a perfectly reasonable answer for. This only makes them more frantic, more determined to take him down. But what they don’t realize is that they can’t take Davey down. He hasn’t done anything wrong. Still, something about all this doesn’t seem right. But neither we nor Margo nor the Reddit users can figure out what it is. Is Davey hiding something? Or is he yet another victim of a society who will do anything to get their piece of flesh?

I have to say, this one kept me guessing.

And I’ll explain why.

I want everyone to imagine the version of this story that came into their head when they read the logline. It probably went something like this. A young female publicist goes to an older entertainer’s home for an AMA. A hacker comes into the AMA. He starts exposing #metoo’ish secrets from the musician’s past. Our musician character fights back, denies, tries to explain it away, cover his tracks, until finally the hacker exposes him as the evil predatory monster that he is. He even tries to assault our poor little heroine.

The fact that you would’ve written that version of the story is why this writer has moved into the professional ranks and you haven’t.

When you come up with an idea – especially an idea inspired by headlines, like this one – it is imperative you not give us the execution we’re expecting. One of the first things the professional screenwriter asks when they come up with an idea is, “What is the movie the audience expects me to write?” Once they have that locked down, they make sure they don’t write that movie.

That doesn’t mean they won’t include parts of that movie. In fact, it’s advantageous to do so. In order to use an audience’s expectations against them, you must start by leading them down a path they expect to be led down. However, the further into the woods you get, the more you should be veering off that path.

I don’t want to spoil this script since it has a lot of surprises, but I’ll say this. There’s a moment after the midpoint where you realize Davey is innocent of the charges these people are leveling against him. Once that reality hit, I had no idea where the story was going. I thought I knew. I thought for sure I was getting the obvious version of the story. The fact that Wikstrom didn’t give me that was awesome.

Another thing I admire about AMA is how big it seems for such a small movie. That’s really hard to do. When you’re writing a typical contained thriller, one of the limitations is that the story feels tiny. A home invasion thriller can be riveting. But it’s only ever a story about those people in that house. What’s cool about AMA is that despite it being a single location movie centered around two characters, it feels huge, because it’s playing out on a world stage. That’s a producer’s dream. To have a movie you can make for so little money that feels enormous.

These types of movies live and die on the dialogue and while I wouldn’t classify the dialogue here as great, it’s pretty good for a thriller. A key component to creating good dialogue is power dynamics. You want to set a power structure between the characters that has one person above the other. This allows for conflict and subtext. Margo has to be respectful, since she works for this person. Davey has enormous power in the dynamic as he’s a legend and knows he can do what he wants. It’s hard to convey exactly why this is important but if you can imagine, for a second, two characters who are on the same level conversing in this situation, you can deduce that their conversation wouldn’t be nearly as interesting as one with this much of a power tilt.

The only thing I didn’t like about the script was that it was hard to buy that this would happen. I’ll give it to Wikstrom that he made sure there were reasons at every turn for why the AMA had to keep going (Margo was being threatened with nude selfies if she quit). But I’m not sure the whole thing passes the smell test. It’s a bit ridiculous. With that said, it was highly entertaining ridiculousness.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[xx] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: The three E’s. Educate, Elevate, and Entertain. Use your story to educate people about something (#metoo). Elevate the idea above what the average writer would do with it (went in a different direction than what was expected). Entertain (package it as a contained thriller). A common mistake with a lot of writers is they only focus on the first two. In other words, they write an uber-serious morality thesis about where we are as a society. Never forget that the first two don’t mean anything without the last one.

I was going to write an article today about why Luke Skywalker is legendary and Rey is forgettable. But I was afraid if I posted another Star Wars article, I would need to place archers on top of my building. The reason I wanted to write the article was because it’s easier to understand why a character works if you compare them to one who doesn’t, and vice versa. But I realized I could explore the same topic utilizing another Disney property, which has a little movie coming up, The Avengers.

Not all of Marvel’s superheroes are created equal. Some are entertaining while others are not. So I thought I’d rank the Top 10 Avengers from most popular to least and deconstruct exactly what it is about the top characters that makes them more popular. If you can identify that, you can take those lessons into your own scripts, and hopefully create better characters yourselves. So first, I’ll give you my character rankings. I understand that not everyone will feel the same way. But I’d be surprised if your list wasn’t at least similar to mine.

1 – Iron Man (Tony Stark)

2 – Spider-Man (Peter Parker)

3 – Thor

4 – Captain America (Steve Rogers)

5 – Hulk (Bruce Banner)

6 – Ant-Man (Scott Lang)

7 – Black Panther (T’Challa)

8 – Dr. Strange (Stephen Strange)

9 – Captain Marvel (Carol Danvers)

10 – Black Widow (Natasha Romanoff)

I’m guessing some of you might put Black Panther above Hulk and Ant-Man. You might put Captain America above Thor. But your overall list probably falls somewhere around what I’ve got.

Now the first thing I want you to do is – and it’s something you should do with your own characters as well – assign a couple of defining adjectives to each character. Tony Stark, for example, might be, “fun” and “a motormouth.” Captain America might be, “stoic,” and “stuck-up.” Do that all the way down the list.

Now notice the adjectives you use for our top three characters: Iron Man, Spider-Man, and Thor. They’re really positive, right? There’s a connection to “fun” with all of them. They’re not afraid to joke around. They talk a lot. They never take things too seriously.

Now look at some of the characters near the bottom. Black Widow, Dr. Strange, and Black Panther. The adjectives that come to mind are more serious. “Calculated.” “Thoughtful.” “Righteous.”

The first lesson we can learn from this is that when it comes to writing for the masses, infusing your characters with personality is going to make them stand out more. One of the toughest types of heroes to get audiences on board with are serious heroes. I mean who wants to be stuck in a room with the serious boring guy? Not me.

How is it, then, that Marvel’s most serious superhero of them all, Captain America, is still in most people’s top 5? Shouldn’t we be bored by him? The answer to that is tricky. I personally think Steve Rogers is as boring as watching soap being made. But I’ll tell you when I like him the most. It’s when he’s paired with Iron Man. The easiest way to make a stoic character pop is to pit them against (or with) a character who’s the complete opposite of them. Iron Man doesn’t take the fight seriously. Captain America takes everything deadly seriously. So you can actually hide a stoic character’s weakness simply by pairing them up with the right person.

Moving on, let’s discuss Thor. Thor is an interesting situation in that he started off lame. His first two movies were some of the worst in the MCU. But he slowly worked his way up into the top 3 by becoming more humorous. And I’ll repeat what I said above. Giving your character personality is a better bet then making them stoic and serious. But blanket personality isn’t the full story here. It’s that Thor is a norse God who isn’t afraid to crack a joke. In other words, his character is pure irony. And that’s why he’s popped lately. He became the embodiment of irony.

What about Peter Parker? Outside of the positive attributes I mentioned earlier, Spider-Man is pure wish-fulfillment. To be a high school kid who’s a superhero… who wouldn’t have wanted that? It’s the coolest thing in the world. And the fact that the character of Peter Parker embraces that and loves it, makes us love him. But really, this is all about positivity, about fun, about having a personality. He’s a joyous character and people like to spend time around joyous people.

Hulk is a tough one. He’s got the biggest inner battle going on of anyone. If he gives in to his anger, he turns into a monster. That’s relatable. When we lose our cool, we all turn into “monsters.” The problem with Hulk’s character is unique to this genre: We don’t want him to succeed. We don’t want Bruce Banner to keep his anger in check because that means we don’t get to see the coolest superhero of all. So we’re actually rooting against him to keep his cool which means we’re rooting against the lesson the character is teaching us (that it’s better to keep your cool). I would still argue, however, that this character is pure fun. Hulk smash. Hulk personality.

Ant-Man exhibits a lot of the attributes of our top three superheroes. So why isn’t he as popular? The problem with Ant-Man is that they made a slight tonal shift that resulted in a character who was goofier and sillier. That shift had consequences. If a character isn’t taking everything seriously, he’s sub-communicating to the audience that we don’t have to take it seriously either. This hurt Ant-Man in the sequel. He’s a prat-falling clown most of the time, which meant, in the end, none of this nonsense mattered. So yes, characters with personality resonate with audiences more. But if you go too far down the spectrum – if you get too goofy or silly (some might call it “Jar Jar Syndrome”) audiences will stop taking the character seriously and disassociate from them.

Black Panther was handcuffed from the start. He’s a King. And kings, almost by definition, have to be stoic. They have to be under control. These are traits that are wonderful in the real world. But in movies? They can single-handedly begin long naps. And so T’Challa is operating from a deficit. It’s no surprise that the breakout good-guy character from that movie wasn’t Black Panther, but rather Shuri, who exhibited many of the traits that our top 3 superheroes on the list exhibit. Black Panther only becomes interesting when he’s challenged by the bad guy (Killmonger). And if that’s the only way for your character to come alive, there’s probably something wrong with the character.

Dr. Strange is not only serious but he’s a know-it-all. He believes he’s always right. But instead of that being a flaw he must overcome, it’s worn as a badge of honor. The character only came alive when he started having some fun in Avengers: Infinity War. Yet more evidence that giving characters personality makes them more likable, and by proxy, more popular. Ignore that formula and you see what happens (Dr. Strange was one of the worst performers in the MCU).

Although it’s hard to examine Captain Marvel without all its baggage, I’ll try. The problem with this character is one of the most crippling mistakes you can make in a screenplay. She’s undefined. On the one hand, she’s a tough serious pilot determined to understand what happened to her. On the other, she’s a wise-cracking Tony Stark clone always on the lookout for the perfect zinger. When you try and do two things at once with a character, it comes off as inauthentic. The audience doesn’t know why the character isn’t working, only that something’s off. And that’s what happened with Captain Marvel. They didn’t define the character one way or the other.

Finally, you have Black Widow. And Black Widow is number 10 for a reason. She exhibits the absolute worst thing you can ever do with a character. She’s bland. There isn’t a single trait of Black Widow that stands out. She’s generic. She’s average. And this is a mistake TONS of amateur screenwriters make. It just happened in a script I read this week. None of the characters had a single exceptional trait. And that’s the quickest way to make a character forgettable.

So what’s the lesson here? Is it to never write a serious character again? No. Keep in mind we’re talking about mass appeal characters. When you’re writing for large audiences, you’re better off giving us heroes with personality. You can write them as serious if you want. But the more serious you make them? The less audiences are going to connect with them. Look at the most serious Avenger of all – Vision. Easily one of the most boring superheroes you’ll meet. Coincidence? Now if you’re writing independent stuff – edgier fare – then it’s okay to drop the big personalities. But your character better be fighting something within themselves. There needs to be a tortured aspect to them to some degree. Cause if they’re just serious people with nothing going on inside, they’re going to be insufferably boring. And that is what I hope people take away from today’s post. :)

Genre: Biopic/True Story

Premise: Based on a true story, a failed New York model transitions into the lucrative world of weed-dealing.

About: Today’s script comes from Elyse Hollander, who you may remember as the writer of 2016’s #1 Black List script, Blonde Ambition, about Madonna’s early days in New York. I refused to read that one for two years because a movie about Madonna sounded boring, but it ended up being great. Unfortunately, the movie will never get made. It makes Madonna look bad. Maybe that’s why Elyse wrote another script, so she can actually get something produced. This one finished with 13 votes on last year’s Black List, which barely got it into the top 20. — For those of you who read my newsletter, I told you last month to seek out a good article to adapt. Well, today, we have another example of what happens when you do that. Queens of the Stoned Age was adapted from a GQ article.

Writer: Elyse Hollander (based on the article written by Suketu Mehta)

Details: 114 pages

So far, nearly everything outside the top 10 of the 2018 Black List has been mediocre. That’s not a surprise. There are usually 5-6 really good scripts a year and everything else lands between “just good enough to get votes” and “mildly entertaining.”

We’ve had some intense debates in previous Black List threads about how arbitrary landing on the Black List is. One of our popular commenters says there isn’t a single script in history that hasn’t made the Black List that deserved to. That in all cases, the scripts that made the Black List are better than every single amateur screenplay. I tend to take a more fluid approach to the argument. I believe that 85-90% of the scripts that make the Black List are better than any amateur scripts out there. But that the last 10-15% could easily be replaced by some of the better amateur scripts floating around town.

So what do those 90% do that you’re not doing? They typically do one thing really well and everything else is at least above average. So they have a really great plot, or they’re good with character, or they’re really good with dialogue, or they have a strong voice. And then there’s nothing else that’s terrible in them. Because that’s what I find dooms a lot of amateur scripts. They’ll do something well, but then the dialogue will be abysmal. Or the characters are so boring. Or the plot is embarrassingly static.

This is why I tell everyone to learn the basics. You can’t cheat that. If you try and skip over something, it’ll come back to haunt you. And you won’t know because you can’t identify a mistake if you’ve never been taught that it’s a mistake. I see this with character writing all the time. The characters are soooooo boring because the writer never learned what you have to do to write impactful characters (conflict within the character, a strong introduction, active, a personality that pops, interesting conflict-filled relationships, making sure they arc over the course of a story).

This is why you should never stop learning. There’s always stuff to get better at, and if you do that long enough, you won’t have any weaknesses. From there, all you need to do is find a great concept and write at least one great character, and you’re in.

So what does Elyse Hollander do better than most writers? Let’s find out.

Honey is a model on the wrong side of her early-20s. She ain’t been booking gigs lately. And she actually owes her modeling agency a ton of money for sponsoring her. If Honey doesn’t come up with a plan quick, she’ll be one of the many failed girls who come to New York and leave two years later with their tail between their legs.

But Honey is different. She’s got a plan. She figures she can start selling weed to people in her friend’s club. Her advantage over other dealers? Guys like buying weed from hot chicks better than smelly fat dudes. Honey’s plan is so successful, she’s soon hiring fellow failed-model friends to help her. When the club closes down for tax evasion, the girls take their racket to the streets, or more accurately, direct delivery.

Soon the operation gets big enough that Honey needs to buy more product, which means dealing with bigger people. This is when she meets Rich, a trust fund son who likes to dabble on the wrong side of the law. This guy, Rich, starts selling Honey her product, but not without expecting something in return. Honey does everything in her power to rebuff Rich’s advances, but at a certain point, it’s give in or bail out. She chooses to bail. And that makes Rich an angry man.

Honey goes to another dealer, Dell, but is forced to buy the product on credit. This turns out to be a horrible choice, as Rich steals all of it in an act of revenge. Dell then comes to Honey and tells her that if she doesn’t pay him back within 48 hours, her friends are going to end up in a New Jersey landfill. Honey will have to use all her wits to defeat the psychopathic Rich, save her friends, and continue to be the Queen of the New York weed scene.

Is it possible to hear someone’s head fall in a script review?

If so, then yes, that was my head falling.

Sigh.

I can’t take it anymore. These people who watch a Scorsese flick then immediately run to their computer to write their screenplay.

The voice over. The tough protagonist who lets you know how the operation works. More voice over. The something bad happens in the first scene. The flashback to “two years earlier.” The voice over. The Scorsese formula is already stale for Scorsese. How are you going to make the imitation crab version tasty?

One of the things that drives me crazy about the Scorsese Formula is that there aren’t any scenes in the first 50 pages of the script. It’s just one long voice over. I like scenes. I like to be in situations. I don’t like someone chirping over my shoulder like a narrator in a World War 2 propaganda film.

I was seriously about to give up on the script.

But then something happened.

Rich.

If this script taught me anything, it’s that a great antagonist can save a screenplay. Ideally, the best character in your script is the hero. But if your hero isn’t up to snuff, you can still land the plane with a killer villain. And Rich the Villain was killer.

He was slimy. He was scary. Every scene he was in, you leaned in closer. There was never point in this script where I had to see Honey succeed. But there were plenty of points where I had to see Rich fail. I hated this rat so much, I kept reading to make sure he got his comeuppance.

A lot of people ask me, what makes a great villain?

The answer is complicated because it’s a mix of ingredients. It’s never one thing. But I will say this: If your villain is only evil to be evil, he’s boring. At the very least, give your villain a REASON to act the way he does. So here, Rich likes Honey. And he’s rich, so he’s used to getting what he wants. When Honey then rejects him, he’s furious. And he will stop at nothing to regain the pride he lost by getting rejected by her. In other words, THERE IS A REASON THAT HE IS ACTING THIS WAY. It’s not just because you need a bad guy doing bad things.

As is always the case with these Scorsese Formula movies, after the endless voice over stops and the movie starts telling an actual story, everything picks up. I was sleepwalking through the first 50 pages. But as soon as Narrator Nate shut up, I became engaged. I liked the scenes. And I thought the drama between Honey, Dell, and Rich was top-shelf.

That’s what I would say gets Hollander on the Black List above the typical amateur screenwriter. She wrote a great character. And despite the annoying Scorsese thing (which is more of a personal annoyance), like I said, she doesn’t do anything poorly. Everything else is either average or above.

If this script were a horse in the Kentucky Derby, it would’ve been last for the first 75% of the race. But it kicked it into gear and slipped into third place at the finish line. So I’d say it’s worth a read.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: One of my biggest pet peeves is when your characters get stopped by the police when they have something in their car that could incriminate them, and instead of cleverly getting out of the situation themselves, the cops just let them go. Please, if you ever write one of these scenes, have your characters outsmart the cops. Characters should earn every break they get in a story. Nothing should EVER be handed to them. If that happens, you’re cheating.

What I learned 2: A writer must always ask themselves, “Is there anything about my hero(es) that might turn an audience off?” Here you have people blessed to be in the top .000001% of beauty in the world. Will we root for these people? Curious to hear your thoughts.

Genre: Horror/Comedy

Premise: (from Hit List) A couple leaves city life behind them for a simpler life in a tiny house. But this idyllic paradise is not all it seems when paranormal activity starts to occur.

About: This script made last year’s Hit List with 8 votes. It was co-written by Paul Soter, a member of the Broken Lizard collective, the guys who made the cult classic comedy, Super Troopers. He teamed up to write this with The Gracias Brothers, who operate a small production company in Culver City (Culver City is where Sony Pictures is located, for those outside of LA).

Writers: Paul Soter & The Gracias Brothers

Details: 104 pages

Tiny House Theme Week continues! And yes, if you’re wondering, I did consider writing this entire review in size 8 pt. font. Assuming you made it out of yesterday’s tiny house alive, you won’t find today’s story any easier to escape, and that’s because we’re not just dealing with any tiny house… but a HAUNTED tiny house.

Before we get to the script, let me take you into the mind of a reader who’s seen every idea under the sun. The concept a reader most fears is an inert one. He reads the idea and he doesn’t see a story. Why doesn’t he see a story? Because there’s no clear engine that’s going to push the narrative forward.

Here, we have this couple who moves into a tiny house, and who we know, at some point, is going to be haunted. That’s fine. Characters being haunted is entertaining when done well. But where is the narrative thrust here? What are the characters going to do in the meantime? That’s what scares me most about an idea – characters sitting around not doing anything. Waiting for the story to happen to them.

Another thing you want in your idea is POP. There’s gotta be that element that pops out and gets you excited about the story. When it comes to comedy, the easiest way to do this is through irony. When I read this logline, I didn’t see any irony whatsoever. A tiny house and ghosts are two random things. When you hear them together, you don’t think, “movie.”

Here’s another logline for you: “A star sumo wrestler’s life is turned upside-down when his minimalist wife convinces him to buy and live in a tiny house.” Yes, I know that’s a dumb idea. No need to point it out. However, can you at least see there’s a sense of irony now? We “get” the conflict.

Needless to say, I saw choppy waters ahead for Tiny Haunted House. But plenty of scripts have surprised me before. Maybe this will be another one.

Uly is a famous pickler living in the weirdest city in the United States, Portland. Well, maybe “famous” is pushing it. He has a steady flow of 10-12 customers who like his pickled products. He’s married to Nan, who looks like she should be in a picture of women eagerly awaiting soldiers retuning from World War 2. Nan is a writer who isn’t a fan of the digitized word. If everything could go back to print, she’d be ecstatic.

The couple is the epitome of happy until tragedy strikes. Their pride and joy, Fillmore the Parrot, is boiled to death during a kitchen accident. Uly and Nan can’t stay here any longer. The memories of their time spent with Filmore would make it impossible. So they decide to move across the country to a place in Massachusetts.

Unfortunately, they don’t have a lot of money. So they need to downsize. Using an online real estate service, they buy a cozy little house with cute pictures sight unseen. When they get there, however, they’re shocked to find that it’s a LOT smaller than they thought it was. Ever the optimists, they make the best of the situation, and within a week, they’re living… if not comfortably, manageably.

Then one day a squirrel leads Uly out into the forest (Uly loves animals – he names the squirrel, “Mr. Nutso.”) and digs up an arrowhead. It’s a little spooky but kinda cool! However then strange things start happening in the house. Like the magnet board keeps unmagnetizing. And a stuffed baby goat animal keeps moving around. And the wood beam at the top of the house drips. But the scariest thing is that a disembodied voice keeps whispering to Uly, “PIIIIIIIICCCKKKLLLLLEEE ITTTTTT.” This places Uly and Nan in the age-old predicament: “What do you do when your tiny house is haunted?”

So was this one of those surprise scripts?

I’ll say this. It’s been a while since I’ve read a script that was written this lovingly. I mean that. This wasn’t something these guys whipped together over a couple of months. Every single line has been pored over to make sure it’s perfect. It was a little jarring, to be honest, cause I’m not used to it. Especially in a script like this, which is basically a goofy comedy. That loving quality infuses the script with a pleasant charm.

But just like I suspected from the logline – there isn’t a whole lot of story here. Once the characters get to the house, there’s no inertia at all. I’m ALWAYS wary when a movie is designed for the characters to wait around for the story to come to them. As I’ve said numerous times on this site, movies work best when heroes are active – are going after things. The ‘waiting around’ effect is multiplied if you plop your characters down into a single location. I mean you can argue that “It” is a movie where we’re waiting around for the clown to do his thing. But in the meantime, the characters are out living their lives, meeting each other, growing their friendship. There’s still a sense that the story is moving forward.

Tiny Haunted House starts to pick up when Nan and Uly realize the house is haunted and start to troubleshoot the problem. For those new to screenwriting, there’s a reason for this. This is the first moment where the characters ACT, as opposed to being acted upon. It shows just how powerful the nature of active characters is. I was bored to tears for 50 pages. And then at least when they call a priest to see if the place was haunted, I was curious what would happen.

The script jumps up another peg when the couple begins to look into the history of the house. Not only are the characters being active but these writers are EXTREMELY original and it’s a backstory unlike anything any other writer would come up with. It’s too bad, really. There’s talent and care and originality put into this script but the first half of it so mind-numbingly slow that it killed the script for me. I couldn’t get back into it no matter how hard I tried.

I’m not going to write this script off. I think some people might like it. But when it comes to tiny houses, I think I’ll stick to Youtube videos. :)

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Use comparison to give perspective when describing size. Saying, “The room is small,” does nothing for the reader. Small means different things to different people. Instead, give us a comparison that puts an image in our head. Here’s the writers describing the bathroom: “Nan and Uly peek into a facility where sink, toilet, and shower all insanely share the same square footage as your average airplane lavatory.” You now know EXACTLY how big the bathroom is.