Search Results for: F word

Save the Cat. The phrase sounds so innocuous and yet it’s become the most popular screenwriting tip in history. More popular than even GSU! For those who don’t know, “saving the cat,” is a term the late Blake Snyder coined that refers to a moment early in the screenplay when your hero does something nice, endearing or helpful to someone or something else. As long as it’s not too generic or too on-the-nose (would we believe that Ethan Hawk would stop running from the bad guys to help a little old woman cross the street?), it’ll make us like your hero. Why has the Save The Cat scene endured for 20+ years? The reason is important so I want you to pay attention. One of the most crucial aspects of making a story work is the reader connecting with the main character. And the easiest ways to solidify that connection is to make them likable. What’s more likable than “saving” someone?

Well the other day I stumbled across one of the best movies ever, The Shawshank Redemption, and I came across a scene that, in retrospect, was the scene that made me fall in love with Andy Dufresne. The reason this particular scene is so important is because Andy Dufresne is considered one of the most likable protagonists in cinema history. After that scene, myself and millions of movie fans liked this guy more than we liked our own friends. So if we can identify what made us fall in love with Andy, we can harness that power to use in our own screenplays. I know all of you are scrambling to figure out which scene I’m talking about. Shawshank has so many good ones, it’s hard to keep track. But before we get to the scene, let’s break down the explanation.

I would argue a more impactful scene than even saving the cat, is a hero’s ability to cleverly out-maneuver the bad guys in the face of adversity. The more clever the character is in the moment, and the more intense the adversity, the better this tool will work. For those of you who’ve read my book, you’ll remember me highlighting one of these scenes. This was before I realized how powerful this scene was so I didn’t give the weight it deserved. But the scene occurred in Terminator 2 at the psychiatric ward when Sarah Connor is running away from the guards. She reaches a locked gate, opens it with her stolen keys, then, as the guards are approaching, reaches back through the bars, inserts the key and then RIPS the top of the key off. When the guards get to the gate, they find that their key is worthless, as the bottom half of Sarah’s key has jammed the lock. This is the epitome of being clever in the face of adversity.

Let’s get back to Shawshank. Now that you have this extra information, do you know what scene I’m referring to? Well, you can watch it right here. Yep, it’s the famous rooftop tarring scene. Now there are a few things going on in this scene but the part I want you to pay attention to is the moment Captain Hadley is running to throw Andy off the roof. This is the highest level of adversity a character can face. His death. Andy then yells out the line that saves him – “Cause if you do trust her, there’s no reason you can’t keep that $35,000.” Captain Hadley stops at the last second, demands an explanation. Andy goes on to inform him of a tax loophole that will allow Hadley to keep his inherited money tax free. After some back and forth, Andy says he’ll even do the paperwork for him, so he won’t have to hire a lawyer. In less than 60 seconds, Andy’s gone from public enemy number 1 to the Captain’s new best friend. You gotta be mighty clever to pull that off. And because Darabont is such a genius, he doubles down! He buttons the scene with a Save The Cat moment – Andy getting beers for his fellow inmates. Is it any wonder, now, why Andy Dufresne is one of the most liked characters ever?

An important distinction I want to make is that being clever is good. Being clever will always make your hero likable. Ferris Bueller was clever. He was always outsmarting everyone. But what turbocharges this tool is being clever in the face of adversity. Real adversity. When we see someone who’s doomed reach into their back pocket and outsmart the bad guys, that’s when the audience feels the warmest and fuzziest. It’s that energy that allows you, the writer, to reach out and join hands with the audience. The both of you are now interlocked as presidents of your hero’s fan club.

Now it’s important to note that the action your hero performs must actually be clever. It has to be something that surprises the audience, something they wouldn’t have thought of themselves. For example, your hero palming a paper clip he later uses to discreetly unlock his handcuffs with won’t do the job. We’ve seen that so many times that we could’ve thought of it ourselves. It must be an act that we wouldn’t have thought of.

Ever wonder why Wesley, from The Princess Bride, is one of the most popular characters of all time? It has a lot to do with William Goldman giving him three scenes IN A ROW where he’s clever in the face of adversity (first the sword fight with Inigo Montoya, second the brawl with Fezzik, and third a duel of wits with Vizzini). One of the reasons The Martian became such a huge book (and later a huge movie) is because Mark Watney is handed a series of obstacles, each of which would ordinarily kill a man, that he cleverly overcomes. First is lack of communication. Next is food. Next he’s critically injured from the air lock explosion. The more we see characters overcome these moments using their intelligence, the more we love them.

So why don’t we see more of these scenes in movies? Because they’re hard to come up with! It’s much easier to save the cat. Have your hero toss a twenty into a homeless man’s cup, follow it with a conversation between the two to show that our hero knows and cares about him, and boom, we’ll like the hero well enough. But that’s child’s play. I can teach a sixth grader to do that. Creating a scenario to show off how clever your hero is is much harder. Which is why, I’d argue, it’s more powerful.

So Carson, if coming up with these scenes is so hard, how do you do it? You do it by identifying your character’s biggest strength. What are they known for? Once you figure that out, you can build a scenario that allows them to show off that strength. Sarah Connor spent a decade preparing to survive. She’s a survivalist. So it would make sense that she’d have a few tricks up her sleeve to outrun pursuers. Andy Dufresne is a tax lawyer. So of course he’s going to know about tax loopholes. Wesley spent years pirating on a ship. He’s spent a decade fighting people. So he’s going to know a few things about sparring with opponents. Find the strength, then create a scenario to highlight that strength.

The reason this works is because it’s built on the concept of us liking people who are good at things. It’s why we can’t look away when Lebron James drives the lane. It’s why we wait with baited breath when Neil deGrasse Tyson is about to answer a question about the universe. It’s why people loved watching Bobby Fischer play chess. We’re drawn to people who are great at things. All this tool is doing is placing that expertise to the most extreme test, when it matters most. And even though it’s complete fiction, we’re entranced by it. We love to see the people we love overcome adversity with their wits.

Sadly, I haven’t been able to come up with a catchy nickname for this type of scene. I’m not clever enough (heh heh). So, I’ll leave that up to you guys in the comments. Whoever comes up with with the best nickname, I’ll give you a free logline consultation. So go at it!

Welcome to 2019!

It snuck up on us, didn’t it?

I had this whole list of things I wanted to get done before the end of the year. Didn’t get to cross anything out. Not to worry, though. This is going to be a great year for screenwriting. I can feel it. And it’s gonna be an even better year on Scriptshadow. Here’s a breakdown of things to come.

Tomorrow, I’m going to post an article on the most underrated scene to write in all of screenwriting. This scene is so powerful, I would place its impact above saving the cat. Unfortunately, I don’t have a catchy “save the cat” like name for it yet. So we’ll have a little competition to see who can nickname the scene tomorrow.

Friday, I’ll be doing a script review. For the weekend, we’ll be having the first Amateur Offerings battle of the year. Let’s start the year off right and find a gem! If you’d like to partake in Amateur Offerings, send a PDF of your script to carsonreeves3@gmail.com with the title, genre, logline, and why you think your script should get a shot.

Monday, I’ll be reviewing Escape Room, assuming it doesn’t have a cataclysmic Rotten Tomatoes score. Why Escape Room? Simple. It’s the perfect spec script premise. If you’re writing a script to sell, you’re not going to get much closer to conceptual perfection than this. Tuesday and Wednesday, I’ll be reviewing scripts. And next Thursday, I’m writing up a First 10 Pages Article, as well as introducing the First 10 Pages Competition. You’ll definitely want to tune in for that.

So a month ago, on a pleasant 70 degree Los Angeles afternoon, I was reading an amateur screenplay. As I finished up the first act, I sat back and sighed. I was bored. Bored bored bored. It wasn’t that the script was bad. Bad implies incompetence. The script was… there. It existed. But that’s all it did. And that’s when a profoundly simple question struck me. Why is it so hard to write a good screenplay? We all love movies. We’ve seen hundreds of them. We know how to BE entertained. But for some reason, we don’t know how to reverse the process and entertain others.

In my opinion, the first problem is effort. I don’t think screenwriters put nearly as much effort into their screenplays as they need to. If you want to write something good, you have to do the boring stuff. You have to do research. You have to outline. You have to do more rewrites than you’d like. You have to write giant backstories for your mythology. You have to have higher standards than the average writer (not settle for “okay” scenes or “okay” characters). Something that drives me BANANAS is when I read a script about a particular subject matter and I know more about the subject matter than the writer! That tells me the only research they did was a cursory glance around the internet. That’s not how good writing works. Not only is a deep dive into your subject matter going to make the journey more fascinating, but the more you know about your subject matter, the more ideas you get. But we live in a time – sigh – when people only do the absolute minimum required. That’s fine. As long as you’re okay with the absolute minimum reaction.

Next, you have to have a good idea. This means a concept that feels larger than life (The Meg), that contains heavy conflict (Fight Club), that’s clever (Game Night), that’s ironic (Liar Liar), that taps into the zeitgeist (Crazy Rich Asians), that’s controversial (Get Home Safe). It takes most writers 6-10 scripts to finally recognize a good idea. Before that, writers write selfishly. They don’t recognize that their idea must appeal to an audience beyond themselves. This results in a lot of nebulous wandering narratives where the writer erroneously believes that just by letting the world into their head, they’re entertaining them. they’re making deep statements about the world.

Actually, one of a writer’s biggest ah-ha moments is when they see an advertisement for a boring movie that nobody’s going to see and they think, “Who in their right mind thought that was a good idea???” It’s only in that small window of time where, if they look at their own script through that same lens, they realize, “Ohhhhhhhhhh. Nobody would want to see this either!!” It’s then when they finally realize this is a business. They now go into the idea-creation process with a new tool – The “Is this a movie people would actually pay to see?” tool. One of the reasons so few writers make it in Hollywood is because they never have this ah-ha moment.

Finally, it’s about execution. Execution is bred from knowledge and practice. How many screenplays you’ve written. How many times you’ve encountered specific scenarios. It took me 10 lousy screenplays to recognize that movies don’t work if the hero isn’t active. For some of you, it will take less. Or, you can simply take my word for it and it won’t take you any screenplays at all. But that’s the case with this medium. You need to repeatedly fail at scenarios in order to know what to do when you encounter them again.

For a long time, I couldn’t figure out the second half of the second act. My scripts would always run out of steam before I got to the third act. That is, until, I read about the “lowest point” second-to-third-act transition. That being when your hero falls to his lowest point (“point of death” some teachers refer to it as) right before the third act. Now that I knew my hero was headed to this “point of death,” I could write towards that.

This is the part no writer wants to hear. But when it comes to writing a good screenplay, a pivotal variable is “time put in.” You have to write a lot. Then you have to write a lot more. Then more. The people who aren’t serious about this craft will fall to the wayside during this period. Just by the fact that you continue on, you increase your chances. At a certain point, you’ll know enough to pass the threshold by which Hollywood identifies professional writing. And assuming you’ve got a good idea with strong execution, you’ll make it. But make no mistake, it’s a long and trying journey. Here’s to conquering that journey in 2019!

Scriptshadow may be on a break til the new year. But that doesn’t mean I’m not thinking of you! Is anyone doing the 10-Day Writing Challenge? How are you holding up? Don’t think, just write. That’s the key to defeating WR (Writing Resistance).

I’ve used this time to relax and catch up on some entertainment. I saw Bumblebee. It was surprisingly good, even if it took the screenplay for E.T. and copy-replaced every instance of “E.T.” with “Bumblebee.” Oh stop. I kid because I love. It was nice to have a director who actually cared about character this time around. A huge upgrade over the original Transformers movies for sure. Another movie I saw was Predator. Oh boy, that was a rough one. For the first 30 minutes, I was convinced I was watching the worst movie of 2018. I mean we have the autistic genius child trope, the Tourette Syndrome trope, the wise-cracking comedy relief trope. If there’s a trope that didn’t get used in this movie, I’m not aware of it. To the film’s credit, it gets better as it goes on. But not by much.

As for Netflix viewing, I tried to watch that John Grisham True Crime series, The Innocent Man. It’s pretty good. If good means boring. An episode and a half in and I know two women were murdered and confessions were made. I knew these things before the show started. Move faster please. I tried to watch that Black Mirror choose-your-own-adventure episode but pressing play informed me that my technology wasn’t up-to-date enough to watch it. Figuring this was part of the fun, I pressed play again. Same message. And again. Same message. Eventually I realized this wasn’t part of the show and that I really did have old technology. I guess no Black Mirror for me.

This turned out to be a blessing in disguise because it led me to check out Escape at Dannemora, the Showtime show that Ben Stiller directed. Ben Stiller is one of the most underrated directors in the business. He’s really really good. And this show doesn’t even utilize his keen directing eye. It’s all about character, acting, and story. I’ve only watched one episode but this may be the best TV show I’ve seen all year. I may do an article on it in the future. So check out the show!

Finally, someone told me about this writing program called Hemingway Editor. It operates within your browser so you don’t have to download anything. The program’s hook is that it assesses your writing on the fly, showing you what’s weak via various highlights. It also tells you (in real time) what level your writing is. I copy and pasted some of my writing on there for fun, and found that the majority of it hovers between 3rd and 4th grade level, lol. Um, can someone say, ego boost? Here I was this whole time aiming for kindergarten. Convinced it was faulty, I copy and pasted some famous works in there, such as a page of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, and her writing is at a 12th grade level!

I’m trying to figure out how it assesses this grade. I suspect big vocabulary words (which Shelley likes to use) may be contributing to the number. Maybe you guys can play with it and help find out. It’s kind of like a video game. What do you do to get your score up? Let me know what you come up with in the Comments Section!

Genre: Biopic

Premise: While a student at Stanford University, Evan Spiegel creates the American multinational technology and social media company Snapchat.

About: This is the number 1 script on the 2018 Black List, which was released yesterday. The writer, Elissa Karasik attended Stansford, and would later work as an assistant to two showrunners, on both Backstrom and Bones (according to The Hit List, which had Frat Boy Genius as its number 13 script).

Writer: Elissa Karasik

Details: 116 pages

The Black List is here and already the complaining has begun! I know the Black List has its issues, but Barky put up a great comment yesterday and I echo everything he had to say in it: “I hate to say it, but most who complain about the quality of the scripts in these lists just have sour grapes. Generally, if you spend any time reading the scripts, it’s pretty easy to tell why there was interest in them. No script is perfect, but there is always SOMETHING, be it concept, voice, character work, etc, that stands out in these scripts. I guarantee you, no matter whose script is up there, someone is going to say it doesn’t deserve to be there. Instead of griping and tearing these scripts down, we should be asking ourselves what it might have been that got interest in the first place, and how we can add such elements to our own scripts.” Well put!

So what are my thoughts on this year’s scripts? For starters, I’m ecstatic that Michael Voyer made the Top 10 with The Broodmare. It wasn’t long ago he wrote me an e-mail confessing he was thinking about giving up. Just goes to show, you gotta keep at it. Normally, I would turn my nose up at the number 2 script, King Richard, as it is yet another member of the tiresome genre known as the biopic. However, a lot of you know my previous life was tennis-centric and Richard Williams was one of the strangest, most controversial figures in tennis for a long time. I’m interested to see if the writer can bring us anything new about him.

Harry’s All Night Hamburgers is a great title and since it’s science-fiction, I’ll definitely check it out. Of course Get Home Safe is in the top 3. The script and its 2-page (or 100 page, depending on how you look at it) FU to white males may have turned a lot of people in the industry off. But the important thing is that it GOT PEOPLE TALKING IN THE FIRST PLACE. It’s hard to stand out when all you have is paper and ink, and Christy Hall figured out how to do it. I’m shocked Cobweb is ranked so high. It’s a very average script. It reads fast, though.

“In Retrospect” reminds me of the old days with its mind-bending high concept. I always felt that like-minded “The Cell” could’ve been a great movie. They didn’t do enough rewrites on the script though. This concept (going into other people’s minds to get something done) is still there for the taking. I feel bad for perennial Black Lister, Gary Spinelli. His script, Rub & Tug was on the fast track to getting made before the trans community shamed Scarlett Johansson for daring to portray them. That baffling play has ensured the movie will never be made (or, if it does, the budget will be 1 million and no one will see it). Not sure what the endgame was there.

Queens of the Stoned Age sounds decent at best, but Elyse Hollander has ensured I’ll read anything of hers after Blonde Ambition. A Vanilla Ice biopic might be too much for me to handle. Unless I light up a stage and wax a chump like a candle. The Fastest Game sounds interesting. I like when writers find a new angle into old subject matter. I’ve heard of gambling before. But I’ve never heard of the sport “Jai Alai.” I want to know more. There was another script about Bob Ross a few years back. This one, Happy Little Trees, with its conflict-heavy logline, sounds a lot better. A logline without conflict is like a burger without fries.

Good to see The Beast made the list as it proves The Black List can still have fun. “Dark” sounds cool. Oil rigs and creatures hidden away for hundreds of years? Count me in. Kill the Leopard has the single most confusing logline I’ve ever read in my life. There may be 17 movies going on in that sucker. “Mamba” is one to keep an eye on. Kobe’s sexual assault case came during a time when that sort of thing could be buried. If it resurfaces as a “thing” in this era, especially with Bryant moving into movie production himself, it could get ugly.

It’s EXCELLENT to see Nicholas Mariani back on the Black List. The Defender doesn’t sound like my cup of tea. But if it’s from Mariani, I’ll read it. For those who don’t know, Mariani wrote the number 1 script on my Scriptshadow Top 25 list, Desperate Hours. I don’t know if I’m reading this right. But I’m pretty sure there’s a thriller on the list about a rabbit. Former Black List topper Graham Moore is back with a new script. His last project about Tesla got buried due to a similar project. Good to see him back in the saddle.

I find it baffling that every year on the Black List, there are two scripts with similar concepts that end up suspiciously close to each other in the vote tally. This year we have both The Second Life of Ben Haskins and The 29th Accident, both about dead partners who come back to life. There’s got to be a glitch in the voting process due to how often this happens.

Inhuman Nature sounds like a comedy set up but I think it’s being sold as serious? Nobody Nothing Nowhere sounds like one of those trippy ideas that could be either really good… or really bad. Wendi sounds okay. I didn’t know that Murdoch’s second wife came from the slums of China.

So, yeah, there’s a lot of good reading ahead. And, no doubt, there will also be some surprises. If you read anything on the list before me, please share your thoughts in the comments section. I’d rather go off recommendations from people I know than randoms. In the meantime, let’s check out the number 1 script on the list!!!

Evan Spiegel, as our title implies, is a frat boy. He is not, however, a genius. At least according to our story’s narrator, Lily, who uses the majority of her voice-overing to paint Evan as an entitled douchebag idiot. But let’s not get ahead of ourselves. One day in college Evan hears a student discussing accidentally sending an embarrassing photo to his mom, which gives him the idea for Snapchat (then titled Picaboo). Snapchat deletes photos several seconds after they’re sent.

Evan teams up with his two best pals, Bobby (who handles coding), and Reggie (who handles day to day operations) and moves to California where they desperately try and get their app off the ground, all while Lily offers her unfiltered thoughts on how dumb Evan is. Eventually, Evan realizes he should be targeting high school kids, and that’s when his app blows up. One of those kids ends up being the daughter of Michael Lynton, then CEO of Sony Entertainment. Michael gives Evan the money to take Snapchat into the stratosphere, and that’s exactly where it goes. The app is worth 13 billion dollars within a couple of years.

Despite it being increasingly unclear why Lily is in the movie, she continues her verbal voice over assault on Evan. The journey culminates in the infamous Sony Hack of 2014, where Michael Lynton’s e-mails are exposed, some of which expose how stupid he thinks Evan is. Evan is furious, goes on a retreat to get his mind straight, then comes back promising to be a better listener. Unfortunately, the damage has been done, and Snapchat is now worth 14 billion dollars instead of 29 billion. We’re left with the now infamous quote from Kylie Jenner, who, with one tweet, temporarily sank Snapchat’s worth by 15 percent: ““Sooo does anyone else not open Snapchat anymore? Or is it just me… ugh this is so sad.”

Frat Boy Genius has an unsympathetic hero and an even more unsympathetic narrator, which makes for a tough read. When you don’t have anyone to root for, why would you keep reading? In the case of Frat Boy Genius, the answer is you want to see how all of this ends. When this much success is attained, when this much money is made, you know you’re cruising towards a wreck. And I wanted to be on the highway when that wreck happened so I could slow down and gawk at the carnage.

But holy hell was the ride tough. Lily, our narrator, is the equivalent of a five year old child who keeps asking if we’re there yet. Except instead of asking if we’re there, she’s making quip after redundant quip about how awful Evan is. Here she is after Evan hits on a random girl. “I don’t have words for this interaction. It’s like you don’t even have to be attractive to be a fuccboi anymore.” There are lots of lines like that.

It’s no surprise, then, that the script picks up considerably during the stretches where Lily disappears. There’s actually a really interesting story here about a guy fresh out of college with a weak app idea who’s in way over his head. Where The Social Network was about the CEO’s control, Frat Boy Genius is about a guy who has no idea what he’s doing having to navigate shark-infested waters, making life-changing decisions on the fly and somehow, impossibly, making just the right combination of moves to create a 29 billion dollar company. When we’re focused on that, Frat Boy Genius is borderline awesome.

Unfortunately, Lily comes back to rain on the 3rd Act’s parade, and the story must weather her irritating Mystery Science Theater’esque opinion on everything. Eventually, we learn why Lily is so angry, which is that she came up with the “Stories” portion of the app and Evan gave her idea to someone else in the company more qualified to work on it. The problem is it’s too little, too late. We already hated Lily with a passion. So the fact that her hatred of Evan is finally explained has no bearing on us.

This is something that could’ve been corrected with a couple of changes. Karasik needed Lily to tell us up front – possibly with a flash-forward – that Evan screwed her over. It’s kind of in there now, but it’s vague. It needs to be clear. That way, we understand why she’s so angry and judge her less for it. The second thing Karasik needed to do was tone down the jealousy and over-the-top anger of Lily. It made Lily come off as a grade-A bitch.

Had she done that, Lily becomes someone we root for, which is something this script needed. Again, there are no heroes in Frat Boy Genius and that makes the story hollow. One of the reasons The Social Network resonated with audiences was that Eduardo, Mark Zuckerberg’s business partner, was once his best friend. We understood how hurt he was by being ousted, which gave the script a stronger emotional through-line. Frat Boy Genius does’t have that because it’s too wrapped up in its own anger.

But I will say this – I wanted to get to the end. I wanted to see what happened to these people. And that’s still a rarity when I read a script. Mostly, I finish scripts because I’m obligated to (we’re going to be exploring this in the First 10 Pages Challenge in the new year so stay tuned!). This one I finished because I wanted to. Which was just enough for me to rate it worth the read.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Have at least ONE PERSON to root for in your screenplay. It doesn’t have to be the hero. It doesn’t even have to be the second biggest character. But we do need SOMEONE. Or else the script ends up feeling sad.

What I learned 2: Vendetta Writing. If you’re writing something with some sort of vendetta, your writing comes across as cruel and one-sided. To write a good screenplay, you need to find the humanity in everyone. We’re all shades of gray. One could argue that the whole point of making movies is to explore that gray area. I would’ve loved to have seen that here.

As we anxiously await the end of the year screenwriting lists, we turn to one of Hollywood’s go-to moves – free IP!

Genre: Fantasy

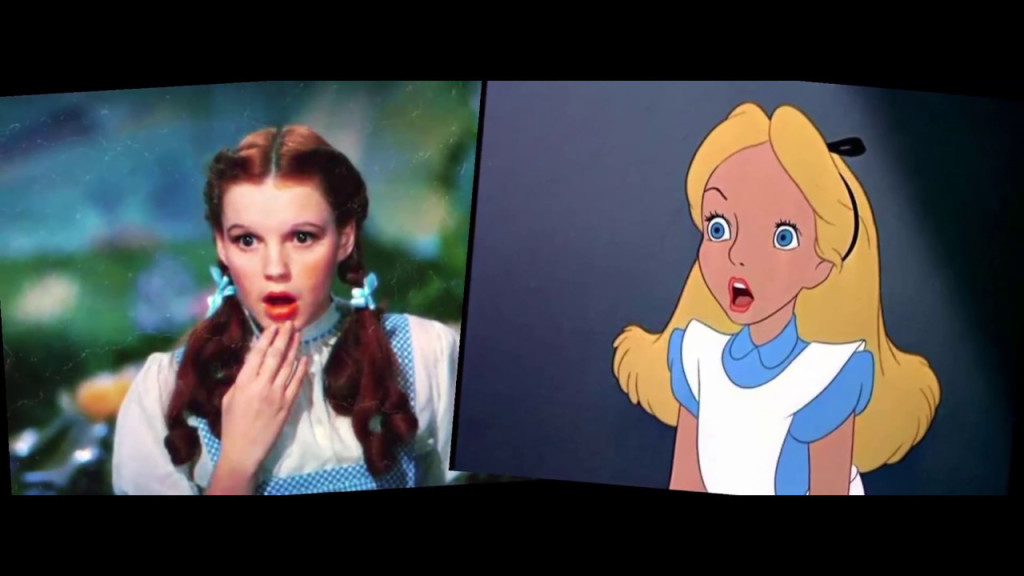

Premise: Dorothy Gale and Alice meet in a home for those having nightmares and embark on a journey to save the imaginations of the world.

About: This script made last year’s Black List. The script was involved in a bidding war and eventually got gobbled up by Netflix. This is an intriguing purchase in that this film will cost at least 120 million dollars (probably more). It’s also an indication that Netflix is now poaching on film studios’ favorite material – old IP. The writer, Justin Merz, is an English teacher.

Writer: Justin Merz (based on the characters created by L. Frank Baum, Lewis Caroll, and J.M. Barrie)

Details: 114 pages

When in doubt about what to write next, turn to the classics.

Cain and Abel, Shakespeare, Wizard of Oz, Frankenstein, The Count of Monte Cristo, dare I say ROBIN HOOD(???) – I just did. I said Robin Hood. But it’s true. Hollywood never tires of these stories because they tick two of the most important boxes in production. They are KNOWN TO EVERYONE and they are FREE TO LICENSE. That’s profit on both ends, baby. And yet, Hollywood’s been screwing up the formula. They’ve got the Robin Hood Problem. The Pan Debacle. The Frankenstein Atrocity. And when was the last time someone gave us a good Shakespeare adaptation? It’s been so long, it’s starting to feel like it was back when Shakey was alive!

I suspect that there are so many options bouncing around our field of vision these days that if we whiff even a HINT of dust on a movie, we’re out. “We’ve seen this already!” we scream to our glowing portals. Only for the studios to be confused when we don’t show up to their latest CGI debacle. The trick to writing in this genre is you have to make it feel new. That’s the only way to wipe the dust off. And hence I give you Dorothy & Alice, a script that will attempt to reinvent a story we know by combining TWO tales into one. Let’s see if it works…

It’s 1901 and an 18 year-old Dorothy keeps having nightmares where she tries to get back to Oz but can’t find it. UNTIL NOW. Dorothy digs under some dirt, finds the yellow brick road, which leads her to someone named Ozra – protector of the Emerald Tower – who informs her that she needs to find something called THE DREAM STONE stat! If she doesn’t, it’s likely that the Red Prince will. And if he gets the stone back to his mommy, it will allow her to destroy any reality – Oz, Wonderland, Neverland, even Earth!

Dorothy’s cool uncle (her aunt has since died) believes that her crazy dreams are real and sets her up with a dream specialist who lives all the way out in London. Once there, Dorothy stays at a special hospital for girls who have wild dreams like hers. She’s thrilled when the head doctor, Dr. Rose, believes that Oz exists. But the good vibes don’t last. A crazed former patient named Alice pops in and recruits her to come to Wonderland where it’s believed the Dream Stone is located.

When Dr. Rose learns that the girls have escaped, she sends two of her men to neighboring Neverland through a Matrix-like contraption that allows people to jump into the dream world at will. Dorthy and Alice travel across the magnificent Wonderland, only to get picked up by Princess Tiger Lilly, who whisks them off to Neverland. Once in Neverland, the Red Queen arrives looking for the dream stone and, wouldn’t you know it, the Red Queen is Dr. Rose!!! Spoiler alert. From there it’s a battle to secure the dream stone and the good guys win and it’s all happily ever after………. or is it?

So here’s the deal.

I can’t stand scripts that are one giant CGI fest. For starters, when it comes to worlds this unique, it’s hard to imagine what we’re looking at based solely on words on a page. But, more importantly, when you write these movies, you risk slipping into CGI dependency, where the answer to your story problem becomes an enormous set piece on top of a giant rose with 50 foot monsters attempting to eat your hero.

The irony of a scene like this is that it’s both imaginative and unimaginative all at once. Sure, we’ve never seen it before. But we’ve seen enough stuff like it where it isn’t interesting. It’s much harder, and more rewarding, to come up with an emotionally resonant character-driven scene. But the more you fall into “GIANT CGI MOVIE MINDSET,” the less likely you are to go with that option.

I actually liked how this script began because it was character driven. I thought it was a really interesting question the author was posing – What is your life like three years after going through an incredible experience that nobody else believes you went through? Imagine how frustrating that must be. And when you add the death of Auntie Em, it makes Dorothy’s situation even more sympathetic.

I WANTED TO WATCH THAT MOVIE.

I even liked it once we got London. Again, it was because the writer was forced to write real things. Just to be clear about what that means – I believe that readers are attracted to things that they can relate to in their own lives. That’s a big reason why Harry Potter is so popular. It mirrored the school experience everyone goes through. When we get to London in Dorothy and Alice, we’re still dealing with real world things like settling into a new place and meeting new people.

Once we get to Wonderland, all of that goes out the window. It’s one CGI experience after another. And while I understand that a lot of this is inherent to the concept (it’s called WONDER-land, so there has to be plenty of wonder), that doesn’t mean you throw out the tool that helps the reader relate to what’s going on. You can ALWAYS use that tool, no matter how insane the world you’re writing about is. In Raiders, it’s the broken relationship between Indiana and Marion. Who hasn’t had to navigate a broken relationship before? It’s the thing that reminds us these people aren’t that different from ourselves.

I don’t know what the flaw or conflict or relationship issue any character here is going through. All I knew was that every ten pages, there’d be a new creature. That’s lazy. Not engaging.

Something that amazes me every time I think about it is the climax of The Matrix. It’s the epitome of the argument that character is more important than spectacle. The climax of The Matrix takes place IN A HALLWAY. The background is WALLPAPER. Think about that for a moment. That’s how minimalist the movie is. And we’re talking about a film that pioneered special effects. Yet the final battle is as simple as it can get.

I try and tell every writer I can about this scene because it’s more than just an example. It’s a way of thinking. When you’re struggling with your script, the solution is rarely to come up with the best action or chase or explosion scene ever. But rather, it’s to explore who your character is and how you can use this experience they’re in to test them.

A lot of you are probably confused now because I’ve gone on this whole rant yet Dorothy And Alice sold to Netflix. So why did it sell? I don’t know. But I can hypothesize. My guess would be that Netflix wants to get into the IP game. And going with free well-known IP is one of the easiest ways to do it. The writer DID come up with a new take, which is to combine two worlds. I suspect that that also had something to do with it, as it gives them unlimited options for sequels if the film does well. And the script is written well. I’m not saying this script is bad by any means. It provides spectacle if that’s what you’re looking for. My argument is that this stuff doesn’t resonate unless you prioritize character over spectacle. And I didn’t see that here.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: As a counter-argument to my review, I will admit that these kinds of scripts are good for writers who want to show that they have the ability to write big set-piece laden Hollywood screenplays. The scripts themselves don’t often sell. But if you can be consistently imaginative, and write even two REALLY INVENTIVE set pieces, that could get you an assignment on one of these effects-heavy projects. — HOWEVER, if you do that AND YOU NAIL THE CHARACTERS, you will be desired by every major studio in town.