Search Results for: F word

Genre: Drama

Premise: (from Hit List) A Texas lowlife is “born-again” and, over the next 20 years, builds an empire out of a prayer circle in his backyard, spanning publishing, broadcasting, and politics; all while fending off demons from his past.

About: Today’s writer, Jesse Maiman, studied screenwriting at Yale and currently teaches film history at the New York Film Academy. While he does not yet have a writing credit, he did produce the 2015 collection of short films, “The Heyday of Insensitive Bastards,” which starred James Franco, Kate Mara, Kristin Wiig, and Natalie Portman, among others. Being Christian finished on the 2016 Hit List.

Writer: Jesse Maiman

Details: 113 pages

We’re only 10 days away from the 2018 Hit List, a list of the best spec screenplays of the year (not to be confused with the Black List, which includes ALL scripts written during the year, including high profile adaptations and writers writing on assignment – that List comes out December 13). Over the last couple of years, I’ve found that The Hit List’s Top 10 more accurately represents the best scripts of the year compared to the The Black List’s Top 10. After those 10, however, The Hit List can’t compete, since it’s pitting mostly unknown screenwriters attempting to break in with spec scripts against seasoned writers getting paid six figures to adapt high profile material. Today’s script finished JUST INSIDE the top 10. Let’s see how it did.

The year is 2001 and John Christian Hillcox has become one of the most popular preachers in Texas. He’s also become one of the richest. And as we’re about to find out, a lot of that money wasn’t exactly earned. Within minutes of meeting Christian, we shoot back to the beginning of his life, where he’s being parented by his alcoholic sexually abusive father, Mason.

The evil that was his father inspired Christian to do everything in his power to make something of himself. Unfortunately, success was a long way’s away. As a junior in high school, Christian knocked up a classmate, and was told by her uncle that if he didn’t make an honest woman of her, he’d kill Christian. And so Christian got married to a girl he didn’t even like at age 16.

Once out of high school, Christian was desperate for money, and so teamed up with a gnarly acquaintance who knew how to hustle illegal aliens into America. The two got good at it, except for one hot day where they opened the door to freedom only to find their entire cargo dead from the heat. Actually, there was one young woman still alive, barely. That didn’t last long, as Christian covered her mouth with a towel and suffocated her. Couldn’t have witnesses.

Christian decided running aliens across the border wasn’t for him, and looked for other sources of income. That’s when he met a local preacher who told him the words that would change his life. If you sell Jesus, you can make more money than you can dream of. Christian took that advice to heart and quickly began shooting up the preacher ladder. And when it came time for his followers to donate to the lord, Christian kept anywhere between 70-80% of the money for himself.

When Christian found out that his wife had self-aborted their baby with a coat hanger, he divorced her, which is when he met Darlene, a Texas woman who loved money almost as much as he did. As their fortunes grew, the people Christian hoped were gone forever, came stumbling back. His abusive father, for one. Oh, and that guy who knows Christian killed an entire family of Mexicans. Can Christian keep them at bay? Or will his past come back to kill him?

Man, this script has it all!

Rape. Gay Preacher Sex. Stealing mass amounts of money. Pedophilia. Underage sex. Illegal aliens. Murder. Abortion.

Nothing is left off the table here. And, to be honest, I don’t know what to make of it.

Being Christian incorporates one of my least favorite narrative devices out there – the “Backstory as Story” Device. That’s when there is no present. There’s only what happened in the past. Since movies work best when they’re in the present, this approach is as problematic as they come.

The only person who knows how to do it is Scorsese. And even he fails sometimes. The only movie where this device truly shines is Goodfellas. And there are a couple of big reasons for that. The first is that the movie starts with a great teaser. A group of guys are riding along. Everything seems normal. Then we hear bumping. They stop. They go to the back of the car. We see that they’ve got a body inside the truck. It all of a sudden starts moving. And they begin beating it.

The reason this is relevant is because it creates a sense of curiosity in the audience. We want to know who these guys are and how the hell they got themselves into this situation. Therefore, we’re willing to do a little work in so far as learning about their past before we come back to the present.

Being Christian doesn’t have an intriguing teaser. We hear Christian preaching. Then we see him having sex with his wife. There isn’t a whole lot of curiosity built up by these events and therefore we’re less patient going into the backstory portion of the script.

The second thing that Scorsese does well with Goofellas – and he does it well with Casino also – is he gets very specific in how he details the world (crime for Goodfellas and casinos for Casino). That level of specificity means we’re learning a bunch of cool stuff about this world. And that’s fun. It’s also rare. Most writers don’t know any more about their subject matter than you do. So the stuff they detail turns out to be stuff you already knew. I would say that 80% of what I know about casinos to this day comes from watching Casino.

Being Christian doesn’t take us that deeply into the world of preachers and televangelists. Which is a second strike against it. So with each passing page, I was getting more and more bored. However, what Being Christian lacks in curiosity and detail, it makes up for in pure what-the-fuckness. This Christian dude is so bonkers that you can’t help but keep reading to see what craziness he’s going to get into next. I mean, when I read him killing the illegal alien, I was like, “What in the world is going on right now!???” I was abhorred, but I’d be lying if I said I wasn’t intrigued. If something as messed up as that could happen, what else did this script have in store?

Being Christian also utilized another Scorsese staple – dueling voice overs. At first, we’re hearing the movie solely through Christian’s voice over. But when Darlene arrives, we start getting her take as well. The choice doesn’t do much to improve the experience, and I would argue it actually hurts it. A lot of times writers will incorporate choices without considering whether they actually add to the story. Hearing Darlene’s inner thoughts is jarring at first, but, in the end, doesn’t tell us anything we don’t (arguably) already know.

Let this be a reminder to all writers to never incorporate things because they feel fun or cool or cause you saw it in one of your favorite movies. Just like a director should have a reason behind every shot (go handheld if you want to create a sense of unease), a screenwriter should have a reason behind every device. Otherwise, it just feels like you’re copying your heroes.

With all that said, the script remains entertaining throughout. Religion is one of the best ways to unleash one of writing’s most powerful tools – irony. Writing bad people who operate behind the veneer of religion works like gangbusters when done well. And Christian may have just become the poster child for it.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: “Unable to resist any longer, Christian and Tiffany grab each other’s faces and there’s a mess of tongues and lips.” I love this line. I love it because it’s a great example of adding a little something extra to the description. Most writers would’ve written, “Unable to resist any longer, Christian and Tiffany grab each other’s faces and kiss wildly.” “…a mess of tongue and lips” is so much more playful and descriptive. Turbo-boost your phrasing to give your description a little extra kick.

At times, screenwriting can feel overwhelming. From flaws to acts to conflict to irony to theme to subtext to arcs to suspense, the sheer number of stuff we’re asked to incorporate into a screenplay can seem paralyzing. Which sucks because once we start to fear writing, we’re less likely to write. And you’re not going to finish any screenplay, much less a great one, if you’re not writing. Which is why today, we’re going to strip all the complexity away and remind ourselves that writing is simple. Here are ten guidelines that should make your next screenplay easier to write than baking a pumpkin pie.

1) Make sure your idea is built around a goal – A goal driven narrative is one in which the hero is going after a goal. Raiders of the Lost Ark (find the Ark), Avengers Infinity War (stop Thanos), Searching (save the daughter), Murder on the Orient Express (solve the murder). The majority of problems screenwriters run into come when they write non-goal driven narratives. That’s because it’s less clear what the main character should be doing (since they’re not chasing a goal), and this leads to wishy-washy plots. Yesterday’s script, The Toymaker’s Secret, is a good example. There wasn’t really a goal in the story. It was a bunch of toys trying to stay out of the way of the new owners. Not surprising, then, that the script had a “Where the heck did that come from?” third act.

2) The goal comes from the problem – If you don’t know what your hero’s goal should be, it’s simple. It’s whatever the result of the problem is. In almost every movie, somewhere in the first fifteen minutes, a problem arises. In Jaws, it’s the arrival of a killer shark. In Misery, it’s that the writer’s car has crashed and he’s been kidnapped. In Halloween, it’s that Michael Meyers has escaped. In The Martian, Matt Damon is stranded on Mars. To find the goal, introduce a problem.

3) Make sure the story feels like it matters – There must be a sense of importance to your story or audiences will be uninterested in it. One of the reasons Tag was such a dud was because there was no sense of importance to the story. Who cares if a bunch of friends finally tag their elusive buddy? Meanwhile, in the movie that the film was modeled after, The Hangover, if the friends don’t find the groom, he misses his wedding and possibly dies.

4) Make your hero likable – I realize not everyone likes this rule. But since we’re talking about KEEPING SCREENWRITING SIMPLE, I suggest you adhere to it. If we like your hero, we will forgive nearly any other mistake you make. Check out Swingers. It’s an AWFUL plot. There’s no overarching goal. The characters wander from party to party, state to state. There’s no purpose, no destination. But Jon Favreau made sure, at the beginning of that screenplay, that you fell in love with Mikey (who gets dumped) and Trent (who cares only about making Mikey feel better). And so we didn’t care about the plot. Also check out “The Gal Who got Rattled” in The Ballad of Buster Scruggs. That narrative is a little wonky. But boy do they make sure you fall in love with Zoe Kazan. She’s earnest, thoughtful, kind, and wants to do the right thing no matter what.

5) Show don’t tell – This is one of the most oft-quoted screenwriting rules in existence. Yet writers continue to fail at it in almost every amateur script I read. A character, for example, will shoot an arrow to kill the bad guy in the climax. Except I’ll have no recollection of the hero ever knowing how to shoot an arrow. How does that work, I ask the writer. “It’s on page 27,” the writer replies, defiantly. “His best friend, Nick, says, “You don’t want to mess with Jake. He can shoot an arrow 100 yards and hit his target dead-center.” WELL OF COURSE I didn’t remember it. A character SAID it. Readers never remember that. They only remember when a character DOES it. If you want us to know that Jake can shoot an arrow, you have to SHOW us that he can shoot an arrow!

6) Obstacles, obstacles, and more obstacles – If you really want to distill a story down to its essence, all it is, is a) a character with a goal, b) that goal matters, and c) he encounters a bunch of obstacles along the way. Your job, then, is to create those obstacles. His wife leaves him. He wakes up in the trunk of a car. His house just blew up. The bad guy keeps popping up at every turn. The monster is getting smarter. The cops think he’s the murderer. He loses his only weapon. His best friend double-crosses him.

7) When writing dialogue, make sure the characters aren’t on the same page – They can be butting heads like rabid mountain goats, or have a respectful disagreement on what needs to be done next. As long as they’re not on the same page, you’re going to have conflict, which is essential for good dialogue. If your characters are on the same page, there’s no reason for them to speak, and therefore no reason to have a scene. Watch virtually any scene in Little Miss Sunshine to see this in action.

8) Instead of summarizing everything in agonizing detail, utilize highly descriptive words or phrases – Screenwriting is about distilling everything down to its bare essence. Therefore, instead of taking five paragraphs to describe how disgusting your hero’s apartment is, simply describe it as a “rotting pig sty.”

9) Stay away from the past – That means avoid flashbacks. That means stay away from elaborate backstories. Movies work best when characters are trying to figure things out NOW, in the present. This doesn’t mean the past won’t come up (Obi-Wan telling Luke he remembers fighting with his father in the Clone Wars). This doesn’t mean you can’t allude to the past (a character mourning the recent death of their spouse, for example). But this should never be the focus. The focus should always be the present. That’s where stories possess the most energy.

10) Contain your time frame – Movies work best when the timeframes are contained. Under two weeks is preferable. 72 hours is perfect if you really want your script to move. But any timeline that “frames” your movie will work. For example, Jaws takes place during one summer. There’s something about knowing where the destination is that solidifies the structure and comforts the viewer.

And there you go. Now get some writing done this holiday weekend. I’ll see you on Monday. Happy Thanksgiving!!!

P.S. This pizza has turkey, gravy, stuffing, and cranberry sauce. Now if only I could convince my family to adopt it as our Thanksgiving Day meal.

Genre: Family/Drama/Fantasy/Animation

Premise: A group of old fashioned toys live comfortably in an abandoned house. However, their world is turned upside-down when a single mother and her daughter move in.

About: This is Alex Garland’s latest script. He wrote it for his wife, Paloma Baeza, to direct. This would be her first feature. She’s directed four short films. The most recent, Poles Apart, is an animated film about a polar bear who meets a grizzly bear for the first time. Helena Botham Carter voiced the polar bear.

Writer: Alex Garland

Details: 106 pages

Alex Garland is one of my favorite writers. I loved his last two films, Ex Machina and Annihilation. And if you want to go back a ways, I thought his novel, The Beach, was excellent. So I’ll read anything he writes. Even if it’s a children’s story! That is, of course, if this is a children’s story. The Toymaker’s Secret is a bizarre amalgam of genres – family, horror, fantasy, ghost story, comedy, drama – which works in its favor sometimes, and against it in others. I guess you might call this a “darker” version of Toy Story. Let’s check out the plot.

In East London, 1891, the Toymaker is on his deathbed. It’s here where he tells his apprentice that it’s time to pass on his secret – the secret of bringing toys to life. The apprentice is crawling out of his skin, he’s so excited. But first, he brings up a quibble.

“Master, one question.”

“Speak.”

“Why?”

“Why what?”

“Why wait for the deathbed? Wouldn’t it have made more sense to have told me this days ago?”

“I just said. It’s the way it’s always been. Since the days of Merlin.”

“Yes, but just given the importance of the secret, it seems so risky to wait until now.”

“Well, there’s a nice symmetry, isn’t there? At the moment of death. Passing the secret of life.”

“But it does make the timing unnecessarily critical.”

“Well quite. And given that time is fast running out — “

“— But what if something had happened to you? You could have been hit by a horse-drawn carriage.”

“That’s exactly why I look both ways before crossing the road.”

“Or been struck by lightning.”

“Could we address these questions after I’ve imparted the secret, rather than before?”

The Toymaker then brings the apprentice close and whispers the secret. Moments later, he’s dead. The apprentice jumps for joy. But not for the reasons we think. “You old fool. I see it all now. The greatest secret in the history of mankind. And for centuries, it has been wasted on children’s toys. But no longer. I shall use it for a very different purpose. I shall build an army of mighty automatons. All shall fall before me like dry wheat beneath the scythe! And I shall rule THE WORLD!”

The apprentice then runs outside, gets hit by a horse and carriage, gets struck by lightning, and dies.

Cut to Alfred, a teddy bear, Tulip, a doll, Celine, a snake, and Gawain, a knight, watching from the window. The toys realize they’re on their own now, and when a new family moves in, they’re forced to relocate to the walls, where they build a new home. They watch this family live for 80 years, until they are no more. Then they spend the next couple of decades living in the house alone.

That is until Catherine, a single mother, and Emily, her 9 year old daughter, move in. The toys are annoyed, but they’ve done this dance before. Then everything changes when a local contractor stops by to look at the house, and announces that the kitchen ceiling is going to need to be replaced. Since 90% of the toys’ secret home is above the kitchen, this forces them to uproot and move everything to a different section of the house.

When more contractors show up and suggest more changes, the toys realize that if they don’t think of something fast, their secret existence will be discovered. That’s when they come up with a plan to haunt their inhabitants. They do a pretty good job of this, with Tulip allowing herself to be “discovered,” only to pull an Exorcist, twisting her head around and making weird noises.

The only problem is that Emily is on to them. She finds her way into the secret world of the toys and demands to know what’s going on. They confess that they’re terrible “people” and tried to get them to leave. Emily forgives them, but both sides then encounter a new threat. It turns out that a toy the Toymaker never finished has also been living in the bowels of the house. And now he wants revenge for being left by the other toys…

While Rian Johnson may have forever turned the phrase “subverting expectations” into a screenwriting swear word, it’s still something you want to be doing when you’re writing. Subverting expectations doesn’t have to be the opposite of a big twist we were expecting, or the opposite of the climax we all wanted. It can include going against any expectation the reader has, even the smallest ones.

When I started The Toymaker’s Secret and he was on his deathbed and he prepares to tell his apprentice his big secret, I groaned. I’d seen this scene way too many times before. I got ready for a lonnnng read. But then the apprentice asks, “Why wait for the deathbed? Wouldn’t it have made more sense to have told me this days ago?” and I laughed. Not only did it subvert my expectations, but it was a dead-on observation that I’d always wondered myself. I went from skeptical to intrigued.

Then, after the apprentice learns the secret, he screams out how he’s going to make an army of automatons and take over the world, and I groaned again. “Oh,” I thought. “It’s going to be one of those movies.” Then the apprentice runs outside and gets killed. My expectations were subverted a SECOND time. Once more, I was intrigued. I should’ve known better. This wasn’t some weekend screenwriting warrior we were talking about. It was Alex Garland. Lesson learned.

The best thing about The Toymaker’s Secret is the characters, specifically the toys. I loved three of the four toys immediately. Each of them had such distinctive personalities. Alfred was the rule-follower and task-master. Tulip was the overly curious one. And Gawain was extremely serious about his duty. That’s one of the most important parts of the game, guys. You want the reader to know who your characters are. They should never be confused or wishy-washy about them. The lone wishy-washy character here is Celine, the snake. And she disappears into the background as a result. The same will happen to your characters unless they’re DISTINCT. We must know who they are and what they represent. Never forget that.

The worst thing about The Toymaker’s Secret is the plot. Remember that when you stick your characters in a single location for the majority of the story, you are limiting your narrative options. It’s not a coincidence that the word “movie” comes from the verb “move.” Movies like stories that MOVE SOMEWHERE. The exception is when there’s an outside force inflicting conflict on the characters in the location. Like David Fincher’s movie, Panic Room. Those characters are constantly threatened by an outside force.

The Toymaker’s Secret’s narrative is driven more by the impending collision between humans and toys. That’s really the only reason to keep watching. We’re curious how the two are going to meet, and what will happen when they do. This type of story engine can work. It’s just hard. And you can see Garland struggling with it throughout. The plot never truly gets going.

It all catches up to him in the third act, where we throw in the insane toy who’s been locked in the basement the whole time. The “late-arriving villain” is another toughie to make work because we don’t know him well. Therefore we don’t know what he wants. Therefore we’re not scared of him. Therefore we don’t give him a lot of weight. When you try and build your climax around a plot point like that, the results are predictable.

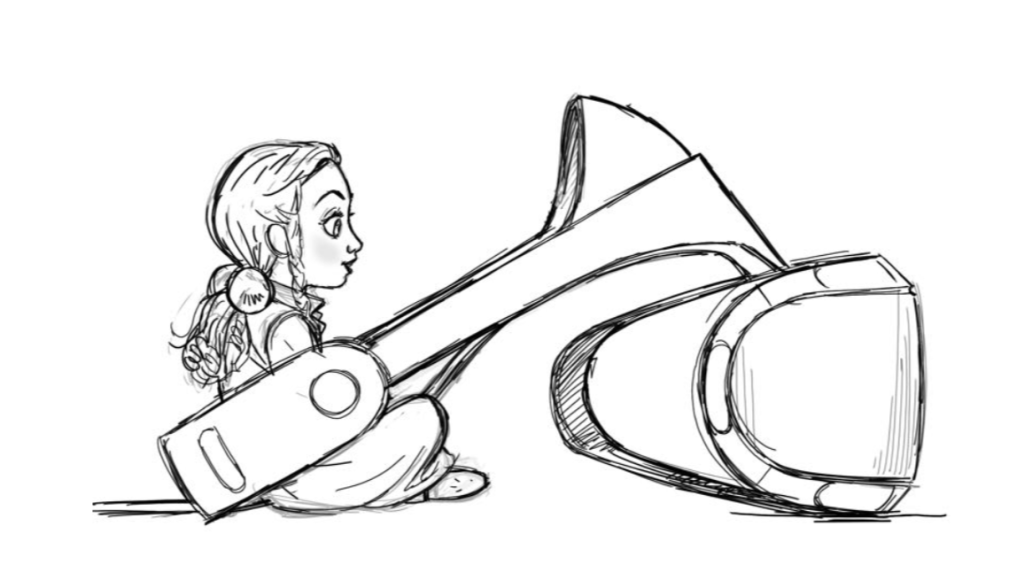

Which is too bad because I loved these toys. I thought Gawain, in particular, was hilarious. And Tulip was adorable. The scene where she sneaks into Emily’s room and uses a VR headset for the first time – rocking everything she knows about life – was wonderful. There’s a movie you can build around these characters, for sure. But this script tries to cover too many bases and, in the process, never discovers what kind of movie it wants to be. With that said, Garland keeps it readable, and I was never bored. So I’d say this is worth checking out.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: One word can add so much to an image. When Tulip is stabbing the contractor’s toe through the wall with Gawain’s sword, Alfred comes flying in to stop her before she’s discovered. Here’s the description.

We are with TULIP, about to JAB SAM again —

— when suddenly she is RUGBY TACKLED by ALFRED.

Garland could’ve easily used “tackled” all by itself. It does the job. But by adding “RUGBY” before it, it creates a much more specific image.

Genre: Comedy

Premise: In the fast-rising sport of Bricklaying, an anti-doping agent and disgraced former champion must take down the champion’s former nemesis, who they suspect is using a bricklaying-enhancement drug known as “Brick Dust.”

Why You Should Read: Bricks of Glory was inspired by a real life event called the Bricklayer 500 which takes place in Vegas every year. They take the top 20 bricklayers from around the world and compete to see who can build the highest (and most structurally sound) brick wall in 60 minutes. A friend of mine’s husband won the Regional Competition in my area so I went to Vegas to watch the show and attended the World of Concrete convention as research. Man, what a trip. I mean they seriously treat this like a major sporting event! I find it so hilarious! So in my script, I completely exaggerate this and make it a much bigger, funnier, spectacle of a sport. Bricklayers use flair, like lighting their walls on fire and juggling bricks, and the competition is so fierce, they resort to taking performance enhancing drugs. I’ve put a lot of work into this script, even doing table reads with stand up comedians to help me punch up the jokes. But if you want to see what inspired it, here’s a video recap of the Bricklayer 500 which should sell it better than I ever could: https://youtu.be/zR69ZFdldH0

Writer: Alison Parker

Details: 103 pages

It’s been 20 years, but the sequel to one of my favorite movies ever – Braveheart – has FINALLY come out (The Outlaw King). Yes, the adventures of Robert the Bruce, starring Chris Pine, arrived on Netflix this morning. The film is stuck at 60% on Rotten Tomatoes. But keep in mind that most of those reviews came in before the director cut 20 minutes from the film after festival showings, massively streamlining it. I’ll be watching Braveheart 2 this weekend and reviewing it Monday.

Today, we’re taking on one of my favorite AO comedy premises of 2018. I’m really excited about this since comedy gets a bad rap on this site. This sounds like a truly fun idea. And while kooky sports comedies have fallen out of favor in recent years, it’s a genre that can easily get hot again. Will Bricks of Glory be the script to do it? Let’s find out!

In the 1960s, when sports like baseball and football grew to record-breaking ratings, greedy sports CEOs looking to take advantage of their fans began charging unheard of sums for balls. The strategy backfired, and within a couple of years, fans completely abandoned ball-centric sports, sending all major leagues into bankruptcy. All of this allowed for non-ball-related sports to flourish, which is how bricklaying became the biggest sport in the U.S.

It’s now 1987 and the star of the sport is 27 year old Wayne Walker, whose theatrical style and killer catch-phrase (“Get laid!”) made him an instant celebrity. His number one fan is his young daughter, Harley, who couldn’t be more proud of her dad. That is until it’s discovered Wayne is using steroids to win! The disgraced champion is stripped of his trophies and given a 20 year ban from the sport!

Cut to 2007 and Harley now works for the World Anti-Doping Agency. Harley is given a task from the president of the agency himself. There’s a new super-powerful steroid being used in bricklaying called “Brick Dust.” The president asks Harley to reconnect with her estranged dad, get him to enter the Bricklayer 500, and exploit his contacts to identify who’s using the steroid so they can shut them down. Along the way, Wayne figures out what’s going on, but forgives his daughter, then enlists her as his bricklaying assistant. The two then team up to try and win the Bricklayer 500 together!

From the moment bricks started getting laid in Bricks of Glory, things were uneven. Alison invents a world where balls become too expensive and all sports collapse, paving the way for bricklaying to become the biggest sport in the world. My issue with this is that you don’t need it. You could popularize bricklaying without having to mention other sports. By introducing this loopy mythology, you rewrite the history books. I mean, we’re supposed to believe that since the 1980s, there has been no basketball, baseball, football, or soccer in the world. I know this is a comedy but that’s some MAJOR buy-in for a premise that didn’t need it.

From there, we have several time issues. The first part of the movie takes place in 1987. A featured scene in that section has our hero being tazed. But police didn’t have tazers in 1987. We then jump forward 20 years, where the rest of the movie takes place. So this movie takes place in 2007? That feels like a really odd year to set a mainstream comedy in if it doesn’t need to take place in that year for the plot to work. If you’re going to set a movie close to modern day, wouldn’t it be smarter to just set it in modern day?

Just to take you into the mindset of the seasoned reader, I’m assuming one of two things at this point. One, that the script is old and the writer never updated the timeline. Or two, they wanted Wayne’s heyday to be in the 80s because it’s funnier than the 90s. They also didn’t want Wayne to be too old when his ban was over, therefore choosing a 20 year ban (making him 47) as opposed to 30 years (making him 57) and accepted the year 2007 as the story year because they didn’t want to do the hard work to figure out how to get us to 2018.

I’ve told you this a million times already but I’ll say it again. If a script starts sloppy, it’s almost impossible for it to recover. I’ve already made so many judgements by this point that I’m nowhere near where the writer needs me to be – which is inside the story, not questioning anything. Again, I realize this is comedy. You can’t apply too much logic. But I also know that comedy works best when it’s simple. And it seems like way too much effort was put into an opening that could’ve easily introduced this premise in a simple way. The concept of bricklaying as a sport alone is funny! You don’t need a bunch of nonsense surrounding it.

As for the plot, I liked that the story was built around a family relationship. I think that’s smart. It grounds the story. It allows us to connect to the characters, as we’re rooting for this broken relationship to be fixed. I just found the whole steroid thing to be uninspired. Who cares about steroids in sports these days? Nobody. But there’s a way bigger screenwriting-related issue at play here. When you come up with a unique concept, you want the problems that arise to be related specifically to that concept. In other words, steroids can be applied to a hundred sports. What’s unique about bricklaying?

I like the idea that people are cheating in the sport. So maybe they suspect that the villain is using an illegal type of brick that’s 10% lighter or something. Or he’s using some caulk (is that what it’s called) that’s 50% stickier, allowing him to stack bricks quicker. Use your imagination. But steroids? I feel like I’m stuck in a time-warp with that storyline.

Bricklaying as a sport is a funny premise. Let’s not overcomplicate it. Set the story in the present. Wayne has been the sport’s poster child ever since videos of him bricklaying went viral a year ago. He’s recently gone Hollywood and isn’t doing the work (think Ronda Rousey). This has allowed a new young Justin Bieber like phenom to gain popularity (who beats him in the regionals). With the Bricklayer 500 coming up, everyone’s picking sides. Use the Rocky 4 structure. Wayne fears that he’s too old to hang with these young guns (which is funny since the sport has only been around for a year and he’s 28), and has to train with the original bricklayer who started it all, go “back to his roots” so to speak, to defeat this young upstart.

Script link: Bricks of Glory

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Times, ages, and dates. Readers are really good at picking up weird time-related issues in scripts. Which is relevant because timing is always changing in scripts. You might decide in your third draft, for example, that your hero’s brother should be 15, not 12. But then you forget to change the age later in the story, when you’ve jumped forward 5 years. You introduce this older version of the brother as 17 (12+5) as opposed to 20 (15+5). When you forget to do this stuff, it looks sloppy. It feels like you’re not on top of things. And that’s how I felt here. Just the fact that the story randomly takes place in 2007 is bizarre to me. And most readers are going to notice that. As annoying as it is, get your times, ages, and dates sorted out before you send your scripts anywhere. It seems like a small thing. But readers tend to judge this stuff harshly.

Yesterday, in response to the Nicholl-winning script, Numbers and Words, coupled with a larger discussion about Nicholl’s propensity to reward scripts with strong social messages, long-time thoughtful contributor Scott Serradell said this in the comment section:

I’m a little funny about the whole goings-on with Nicholl. I just question their legitimacy a bit if writers — knowing what advances in the Nicholl ranks — can then tune their stories to hit the right marks. Is that just tailoring? Or a polite form of trolling?

Well, let’s find out: My next script (and Nicholl entry) is titled “The Only Gay Bar in Gaza” — and it’s basically the brief (but beautiful) tragic romance between an Israeli man and a Palestinian man. Right there, I think I’ve got about 3 or 4 “message” boxes checked off. If I add a “based on a true story” it might just work!

I replied to Scott by saying if he really wrote that script and entered it into the Nicholl, I could guarantee, based on the concept alone, that it would make the semi-finals. If the execution was better-than-average, there’s a good chance it would be a finalist. Scott responded with,

But something about that ignites my cynicism. I mean, that little pitch above took all of 5 minutes to conjure up. And it certainly wasn’t because it was some personal story burning to get out; I merely took an assessment of what attributes the judges might be looking for and tailored (or trolled) my response accordingly. Is it right? Is that ethical? Well, if those are the rules of the game, does any of that matter? — If the broader goal is to get recognized by the industry, am I not obliged to do whatever it takes to set myself outside the pack?

That got me thinking. Not about the Nicholl. But about what happens when you remove yourself from the equation and generate ideas solely based on what you think the gatekeeper will respond to. Are you then better equipped to come up with successful ideas, similar to what Scott was able to do in this circumstance? The crippling x-factor in a screenwriter’s pursuit of writing a breakthrough script is the personal attachment he or she has to the idea. Writers often become fixated on commercially inert concepts simply because they’re obsessed with an aspect of the idea that they have a personal connection with.

This is true of every writer. Even professionals. How many ideas do you have on your computer that you love despite nobody else giving a damn? The reason for that is we have an intense connection to either the character, the concept, or the theme, that clouds our ability to judge the concept objectively. So today I’m asking, what if you removed the variable that’s clouding your judgement? What if you tried to come up with ideas that you, yourself, would never write, but you’re positive would make billions of dollars at the box office? Do you become a better idea-generator under those circumstances?

To see if this is the case, apply the same logic to Hollywood that Scott did with Nicholl. What does Hollywood like? The people who visit this site know the answer to this question better than anybody. They like superheroes. They like giant monsters (King Kong, Robots, Godzilla, sharks). They like horror. They like a guy with a gun. They really like a girl with a gun. Time-travel. Serial killers. Aliens. They like two-handers, especially action-comedy. They like biopics about people who led fascinating lives. They like true stories that involve heroism. They like the apocalypse. They like heists. They like irony.

Today’s post is more of an experiment than anything. Maybe my theory is wrong. But I’m curious to see what you guys would pitch if you had zero vested interest in your idea, and were only pitching what you were convinced Hollywood would go bonkers over. Is it as simple as saying, “A biopic about Horace Smith and Daniel B. Wesson, the founders of Smith and Wesson? Here’s my routing number. Transfer the 5 mil by Friday, thanks.” Or “A female FBI agent is tasked with putting together a team to take down the biggest crime organization in the city, which happens to be led by her father (or mother).”

Remove yourself from the equation and pitch your surefire Hollywood hits in the comments. Upvote any pitches you like. Let’s prove or disprove my theory by the end of the day.