Search Results for: F word

Guess what time it is? It’s time to venture into the SECOND ACT!

NOOOOOOOOOOO!!! you say.

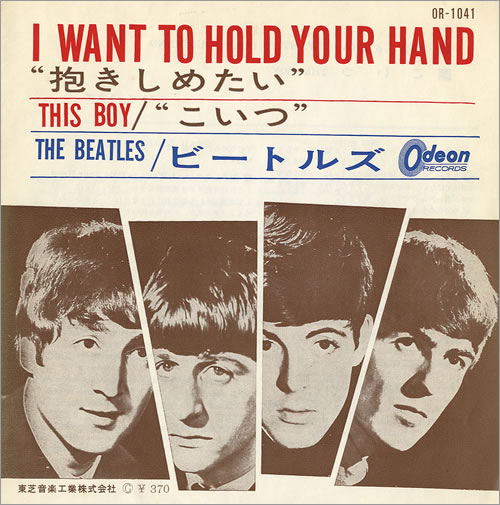

Don’t worry, my screenwriting salsolitos. Just like The Beatles, I’m going to hold your hand.

For those of you new to the site or you infrequent visitors, I’m doing a 13 week “Write a Screenplay” Challenge, where I guide you through the process of writing a screenplay step by step. If you missed the first few weeks, you can find them here:

As of today, you should have written 21 pages. That means you’ve completed your inciting incident (located near page 12-15) but are not quite at the end of your first act (page 25). So today, we’ll be covering the break into Act 2, as well as the first sequence of Act 2.

Now I heard some grumbling last week about 3 pages a day being too difficult. Come on, guys. Seriously? That’s one scene. You only have to write a single scene. You’re telling me you can’t write a scene in a day??

Maybe this will help. Brendan O’Brien and Andrew Jay Cohen said that when they were trying to figure out their script, “Neighbors” with director Nicholas Stoller, they’d pitch him a bunch of directions they could go, thinking he’d pick one and let them go write it.

Instead, Stoller would say, “Well let’s try that version right now.” “What do you mean right now?” they’d ask. “Let’s sit down and write it and see if it works?” “You mean write the script… now??” “Yeah.” And they’d sit down and write the whole thing over a few days. If it didn’t work, they’d try a different take.

The point is, you’re capable of one scene a day. Don’t be a perfectionist. Just write.

Okay, on to this week’s challenge. You’ve got between 4-8 pages before the end of your first act. If your hero is in a refusal of the call situation (Luke Skywalker claims he can’t join Obi-Wan because he must stay and help his Uncle on the farm), this will be the last bit of resistance your character experiences before accepting that they have to go on their journey (pursue their goal).

If your hero isn’t refusing the call, this is the last few pages of logistics before they pursue their objective. Indiana Jones don’t refuse no call. He just packs his bags and prepares for the fun. If your character doesn’t have any say in the matter, the forces of the story will simply kick them out on their journey, much like a bird kicks its babies out of the nest to see if they can fly. Tough love, amirite?

Now in some cases, a journey is literal. Rey’s journey in The Force Awakens takes her across the galaxy. Tom Cruise and Dustin Hoffman take a road trip to Vegas in Rain Man. Joy has to travel deep into the recesses of Riley’s mind in Inside Out.

Other times, it’s more symbolic. As long as your character is constantly pursuing something, even if they’re stationary, it’s considered a journey. To use the aforementioned Neighbors as an example, our heroes may be inside the same house the whole movie, but their “journey” consists of trying to get the frat next door kicked out.

So the first 15 pages of the second act are a unique time in a script. Your heroes are going off on their journey, but since we can’t throw the kitchen sink at the audience right away, this section tends to be more of a “feeling out” period for the characters. Maybe they’re feeling out each other (“Bad Grandpa”) or feeling out the situation (In a heist flick, the characters might scout out the bank they’re planning to rob, or the team they’re trying to recruit).

The late Blake Snyder, whose book “Save The Cat!” is somehow still the best selling screenwriting book out there despite Scriptshadow Secrets being available, famously termed this section, “Fun and Games.” Since Blake mainly wrote comedies, this was meant to define the period in the script where you showed off the promise of your premise.

The best example of this is probably super-hero origin stories. This is the moment when Spider-Man or Ant-Man first get their powers and play around with them. But it can also be applied to other genres. In Jurassic Park, it’s seeing the dinosaurs for the first time. In The Equalizer, it’s when Denzel starts administering justice on the locals.

If all of this is confusing, however, or it doesn’t feel like it applies to your movie, don’t worry. There’s a backup. What’s that backup?

SEQUENCES

Divide your script into a series of eight 12-15 page sequences. You’ve already finished the first two sequences. That was your first act. Now you’re on your third. You have to fill up 15 more pages. The easiest way to do this is to give your characters an objective they have to meet by those 15 pages. That way, you don’t have to worry about this giant chasm-filled void of a second act. You only have to write 5-7 scenes getting your hero to the end of that sequence goal.

A good example is the Mos Eisley sequence in Star Wars. We’re officially on our journey into the second act. What’s the goal here? The goal is to get a pilot and get the fuck off this planet, since the Empire is chasing us. We experience a series of scenes where our characters come to Mos Eisley, enter a bar, look for a pilot, get a pilot, head to the ship’s hanger, get chased by stormtroopers, then leave. That’s a sequence right there, folks. That’s all you have to do.

You can even use this for non-traditional scripts. Room is a movie that’s basically two long acts. It’s divided in half. But if you look closer, you’ll notice that there are sequences to give the story structure. For example, the fourth sequence of that movie (which would roughly be page 40/45 to page 52/60) is Ma (Brie Larson) planning the escape. That’s a sequence folks. It’s got a goal. It consists of a series of scenes. This stuff isn’t rocket science.

Gravity is a great movie to study for sequencing. It’s evenly broken down into a series of sequences where Sandra Bullock constantly has to get to the next destination, which usually takes between 10-15 pages (no, that is not an excuse to procrastinate!).

So that’s this week’s challenge, guys. You have to get 15 pages into Act 2. Seeing as we finished on page 21 last week, that means you only have to write 19 pages this week, which is LESS than 3 pages a day. Which means no more complaining. I’ll see you next week, with 40 total pages completed. And that’s when we head into the HEART of the second act. Ooh, I can’t wait for that. And by “can’t wait,” I mean, “Shit, that’s going to be terrifying.” Seeya then!

Genre: Drama

Premise: After a priest stumbles across the execution of a Mexican family who were trying to cross the border, he finds himself hunted by the killers.

About: This script sold two years ago in a mid-six-figure deal. The writer, Mike Maples, has been at the game for awhile, with his first and only feature credit, Miracle Run, being made back in 2004. Padre was pitched as being in the vein of No Country for Old Men and A History of Violence. Like I always say, guys, find those buzz-worthy movie titles to compare your script to. Whether it be “Fargo on the moon” or just, “This is the next Seven.”

Writer: Mike Maples

Details: 100 pages – undated

There are two types of screenwriters trying to break into the business. There are the ones who grew up on big fun movies who want to bring those same good vibes to the masses, and there are the ones who want to say something important with their work, who want to make “serious” films.

Take a guess which ones have an easier time getting into Hollywood.

That’s one of the first pieces of advice I’d give to anyone getting into screenwriting. Write something marketable. Yet when I run into one of these serious types, the suggestion of marketability is akin to asking them to copulate with a rhinoceros. They feel like they’re “selling out” if they even consider the masses while writing in their vintage 1982 moleskin notebook. It’s almost as if they’d prefer wallowing in obscurity for the rest of their lives, attempting to push that Afghani coming-of-age story, than break through with a strong horror premise AND THEN write their anti-Hollywood film.

Well if today’s script tells us anything, it’s that it IS possible to sell a thoughtful more serious spec. It doesn’t happen often. But it can happen. Let’s figure out what today’s writer did that was so special.

40 year-old Gideon Moss is a priest who lives just north of the Mexican border. While everyone else in the area is furious about illegal immigrants crossing into their country, Gideon regularly delivers water and food to those at the end of their journey.

One day, while on a run, he stumbles across a recently murdered family of Mexican immigrants. A quick look around and he spots, in the distance, a couple of locals staring at him. Doesn’t take much to add 2 and 2 together.

Figuring they’ve been made, the men, a part of a bigger militia, barge into Gideon’s church later that week during a sermon, round up him and all the Mexicans, take them to the desert, bury them alive, then crucify Gideon on a cross. Gotta give it to these guys for creativity.

Left to bleed out, Gideon escapes, and starts hunting the gang down one by one. Oh, there’s one last problem I forgot to mention. The militia? They’re all cops. So it’s not like our pal Gideon can ask for a helping hand. Lucky for him, and unlucky for the baddies, he has a very military-friendly past.

Okay, so this isn’t exactly an Afghani coming-of-age story, but it fits a rule that I push on writers attempting to write “serious” films. Make sure there’s at least one dead body. While there may be a temptation to mirror real life and call your script ‘realistic,’ the reality is that film is larger than life. You have to have at least one larger-than-life element in your story. A dead body fits that criteria.

Also, if you’re going to write one of these serious scripts, you need to be descriptive. You need to have the power of picture-painting. Your world is decidedly less exciting than 12 superheroes battling each other on an airport tarmac. So you have to make up for that in your ability to place your reader inside your world. A truck can’t just drive. It has to exist, as Maples shows us here: “A rooster tail of dust billows behind the truck and hangs in the still scorched air.”

It should also be mentioned that if you’re going to write this type of script, you have to have the skill to actually pull it off. The most painful scripts to read are the ones where writers without any skill try and weave their way through complex descriptive sentences. For example, they’d re-word the above into… “The truck lampoons the stretch of road with forest trees all around it and shifts into gear like a rocket out of hell.” Honestly, I read a lot of lines like that.

Also, you have to have dialogue skills for these scripts. When someone offers to help Gideon, despite the risks involved, he doesn’t reply, “No, your life is too valuable,” he replies, “Leave it be. Your box is thirty years down the line. No use taking a short cut.” That’s a professional line of dialogue right there. Or later we get this exchange, which takes place between the badass villain and one of his dim-witted minions: “What the fuck is this?” “You just squandered five of the ten words in your vocabulary, son. Keep the rest for later.”

Padre also utilizes two tropes that tend to work well in film. The first is the priest who’s not so priestly, and the second is the cop who’s not so friendly. As we like to preach around these parts, always look for irony in your story. Corrupt cops are as ironic as it gets. So are murdering priests. Usually, you only see one of these in a movie. It was fun to read a script where we got both.

And there were just little professional spikes that set this apart from the average amateur script. For example, a little girl is killed in that scene where the bad guys round up everyone in the church and bury them alive. Now normally, a writer would think that was enough. Nobody likes to see a little girl die. We’ll hate the bad guys even more and want to see them go down.

But Maples makes sure that we SET UP A SCENE WITH THIS GIRL EARLIER. So one of the first scenes is Gideon visiting a nurse friend at the hospital. The nurse gives him drugs to pass to the little girl, who’s sick at home because she’s illegal and can’t afford hospital care. Gideon delivers the medicine to the girl, so that we know her and care about her (not to mention doubles as a Save The Cat moment!). That makes her later death a thousand times more impactful. Amateur writers rarely think to do this sort of thing.

If there’s a knock against the script, it’s that it feels a little familiar. There are usually 3-4 of these kinds of scripts on the Black List each year. And I wasn’t a fan (spoiler) of the revelation that Gideon used to be a Black Ops soldier. It seemed like a lazy choice, and honestly, I don’t think it was necessary. Gideon comes off as badass enough that you don’t need to make him even more badass with some backstory title. But outside of that, this was a strong script.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: If you’re going to write a script like this, be honest with yourself and make sure your writing is at the level required to pull it off. I’m not saying you don’t have to know how to write to write “Neighbors.” But the skill level of putting words together is decidedly less important with scripts like Neighbors or Deeper. With drama, you will be judged more harshly on your writing ability, because your job is to set a mood and a tone with your writing, something that takes a lot of time and practice to master.

Welcome to Week 2 of the 13 Week “Write a F#&%ING Screenplay” challenge. Here’s a link to Week 1. If you’re coming into this late, you might be able to catch up. But once we get past this week, I recommend you follow the proper time frame. Give each assignment 7 days. We’re already going fast as it is, so I don’t want you going any faster.

Last week was all about the character bios and the outline. This week, you’re going to be drawing on both, but mainly your outline. Your outline is going to work as a series of checkpoints. You now always have a checkpoint 15 pages away or less.

That’s how I want you to start seeing your script. Not as a giant void of empty space, but a series of manageable sequences, each no more than 15 pages. Each scene averages 2 to 2 and a half pages. So every 15 pages, you’ll be writing 5-8 scenes.

Okay, now let’s get to the nitty gritty. You will be writing THREE PAGES A DAY MINIMUM. It is CRITICAL that you write at least these three pages a day. And that shouldn’t be difficult. You have an outline so a lot of the guess-work of “Where do I go next?” is taken care of. And writing three pages of double-spaced non-paragraph-intense script takes most people between 30 minutes and an hour.

If writing that many pages is hard for you, it usually means you’re being too hard on your writing. One of the most common mistakes new screenwriters make is they become obsessed with the actual written word and want to make every sentence something their English professor would be proud of.

You don’t need to worry about that. Your scene will be rewritten so many times, it won’t resemble what it was when you first wrote it. Therefore, all those extra hours you put into making your sentences perfect will have been a waste. Since nobody saw them anyway.

Perfecting your presentation is something you only want to worry about when you’re putting the finishing touches on a script you’re sending out. That stuff means nothing when you’re the only one reading it. Just write clearly and have fun doing it. The first draft should be the draft that’s the most exciting to write. Because it’s the draft where you’ll discover the most about your story. Don’t stifle that because you can’t decide if you should use a comma or a semicolon.

Three pages a day at 7 days a week means that next week, you will have finished 21 pages, which is kind of a weird place to stop since it’s right between the inciting incident and the end of the first act. But whatever. We’ll work with what we’ve got.

Our main concern is your inciting incident, and since every story is different, I can’t give you a one-size-fits-all solution for this. A script someone just sent me had the inciting incident on the very first page. And they did the same thing with my favorite script, Source Code. Our hero wakes up in the middle of his problem – he’s on a train that has a bomb about to blow and he must figure out who the bomber is.

There are also movies that need to establish multiple characters, like The Force Awakens, so it’s harder for that movie to set up its main character (Rey) and hit her inciting incident right at page 15. I’m guessing the inciting incident there is when Finn shows up at her doorstep with the bad guys in pursuit, and that happens on page 30. Others may say that Rey’s inciting incident is when BB-8 shows up on page 15, though I don’t think that’s a big enough problem to be considered an inciting incident.

The point is, the definitions for these screenwriting terms are fluid and dependent on the unique circumstances of your story. So don’t get too caught up in them if they’re confusing. Just make sure that you have those checkpoints marked. And between now and next week, the only checkpoint we’re worried about is between page 12-15. Something needs to happen there to kickstart your movie or we’ll get bored.

So what do you do in the meantime? Well, the first 15 pages are about setup. You’re setting up your characters. In the old screenwriting books, they’d say we want to meet our hero in their everyday lives. If we don’t see who they are to begin with, we won’t appreciate who they have to become when the shit hits the fan. So again, you saw this with Rey in The Force Awakens. We see her everyday life of scrapping and trying to survive.

If you’re like me, you like movies that start in motion. And in those cases, we won’t always be able to see who your character is in their everyday life. They may not even be in their environment when we meet them. Jason Bourne doesn’t start off in a cozy house in the suburbs making breakfast for his kids. He wakes up in unfamiliar territory.

Regardless of where we meet your character, you have to tell us as much as possible about them in a very short amount of time. If they’re in their environment, that’s easy. By seeing their everyday lives, we’ll get a sense of who they are and what their weaknesses are. If you start them in an unfamiliar environment, go back to that character bio I asked you to write, figure out what their flaw is, and write a scene that exposes that flaw, if not in their introductory scene, then soonafter. So in Trainwreck, we immediately establish that Amy Schumer is…. you guessed it, a trainwreck.

And again, don’t get too caught up in your beats. Every screenplay is like a snowflake. It’s different. It has its own quirks and needs. Okay, maybe that’s not like a snowflake at all but you get what I’m saying. Sometimes you want to start your script with a flashy teaser that has nothing to do with your hero. If that feels right for your script, DO IT! Don’t resist creativity because you’re trying to meet technical checkpoints. Those are there as a guide. And since this is the first draft, it’s okay to color outside the lines a bit.

After you write your inciting incident scene (the scene where a big problem alters your main character’s life forever and forces them to make a choice whether they’re going to fight that battle or throw in the towel), we have 6-7 pages left until next week’s assignment.

The Hero’s Journey, which is a template a lot of professional screenwriters use, identifies this section as “The Refusal of the Call.” Preferably, the problem that your hero is faced with is a big scary one. If it isn’t, you probably don’t have a movie. Because it’s big and scary, your main character will resist it. And that’s what this section of scenes is for. The hero wants to go hide, get away from this, not deal with it. But in the end, of course, they have to. Because otherwise we wouldn’t have a story to tell.

Each genre tends to have its own blueprint for this section, and there’s no way I can cover them all here. But think of this section as a push-pull situation. Write scenes that pull him, “You need to do this,” a mentor might say. Then scenes that push. Another character says, “You need to stay here and help with the farm.” It doesn’t have to be dialogue-based. These can be action scenes – in a sci-fi film, someone’s base can get attacked. Point is, this is a turbulent time where your hero’s every fiber is being tested.

Eventually, something will happen to push your character towards his adventure, sometimes by choice, sometimes by force. In The Hunger Games, Katniss chooses to swap herself for her sister. In Edge of Tomorrow, Tom Cruise never chooses anything. They MAKE HIM go. So just know that you have options and there’s no such thing as ONE WAY to do it.

Finally, writing is a fluid thing. Your best stuff comes when you’re inspired, and you can’t always predict when that’s going to happen. So don’t limit yourself to 3 pages if you’re on a roll. If you write 10 straight pages, GREAT! If you pull a Max Landis and write all 21 in a single day, GREAT!

But if you get to 21 before next Thursday, you don’t get to chill. You have to work on your script for at least 3 pages or 2 hours every day. Part of what I’m trying to instill in you here is discipline. The more writing becomes a daily thing, the more you’ll keep up with it. If you write 20 pages one day and take the next 5 off, it’s harder to come back.

So if you get to 21, go back and start rewriting your earlier scenes. Specifically, ask if your choice of scene is original. Have you seen that scene before in other movies? If the answer is yes, try to come up with a new angle into the scene – a more original choice.

I’ll give you an example. In yesterday’s script, two assistants trying to make their bosses fall in love trap them in an elevator together, hoping they’ll connect. The writer added a THIRD PERSON, a UPS delivery guy, in the elevator as well, who flipped out once the elevator stopped. It added another layer to the scene to make it feel more original. That’s what I want you to do if you have time to rewrite scenes.

If you have gobs of time or your parents are supporting your career, use the rest of your free time to KEEP FILLING IN YOUR OUTLINE. The more scenes you can figure out, the easier future writing sessions are going to be. And you know now that 15 pages is roughly 5-8 scenes. So you know how many scenes you need to fit in between each checkpoint.

Okay, that’s it for this week. Time to get some writing done. 21 pages, people. Good luck!!!

Genre: Period Political Thriller

Premise: Set in one of the most volatile cities during one of its most volatile eras – Beirut in the 1980s – High Wire Act follows a bottomed-out alcoholic diplomat who’s called upon to negotiate the release of a CIA agent who used to be his best friend.

About: From the writer who brought you Michael Clayton and FOUR of the Bourne scripts (Tony Gilroy) comes this hot project, which will star Jon Hamm and Rosamund Pike.

Writer: Tony Gilroy

Details: 120 pages

High Wire Act got me thinking about the types of movies Hollywood makes these days. Cause it ain’t movies like High Wire Act. Unless you have a prestige director and an Oscar campaign ready to roll, I know execs who’d be more welcoming to the Zika Virus than an obscure period political thriller.

Remember when they used to make movies like Boiler Room? Or Rounders? You didn’t even need a concept! All you needed was a subject matter. Uhh… traders on Wall Street. Uhh… poker players! We’ll figure out the story later.

Truth be told, I’m kinda glad those movies don’t get made anymore. They sucked. I mean go back and try and watch one of them. You’re sitting there going: This is basically about a guy named Matt Damon playing poker. They didn’t even try and hide it.

Luckily, High Wire Act is more sophisticated than those scripts, plus it has the benefit of being written by someone who actually understands screenwriting.

Mason Skiles, an American diplomat in 1972 Lebanon, has managed the rare feat, along with his wife, of becoming friends with many of the locals. There’s one boy in particular, 15 year old Kamir, who Mason has personally mentored and will soon send to school in the United States.

Unfortunately, however, school will not be in session for Kamir. A group of masked men crash one of Mason’s parties and take Kamir, who it turns out is the brother of a high profile terrorist. During the scuffle, Mason’s wife is shot and killed.

Cut to 10 years later and Mason is a drunk back in the states with a bargain basement arbitration practice. Just when things can’t sink any lower, he gets a call. It’s the CIA. They want him on a plane to Beirut pronto. But they won’t tell him why.

Mason reluctantly goes, where he finds out that his former best friend and fellow diplomat, Desmond, has been taken. And the kidnappers are requiring they deal with Mason only. Hmmm… that’s interesting.

So Mason goes to meet them and wouldn’t you know it, guess who the kidnapper is? That little boy, Kamir, is all grown up and ready to make a deal. The Israelis have kidnapped Kamir’s troublemaker brother. If Mason can get him back, Kamir will deliver Desmond.

And that’s where things get REALLY complicated. Kamir’s brother is essentially Osama Bin Laden to the Israelis. There’s no WAY they’re going to give him up. Which means Mason is going to have to pull off the greatest negotiation of all time in order to save his friend. Can he do it?

This script starts with a bang and never lets go. My issue with these scripts is that the writer will get too wrapped up in the politics side of things. That stuff isn’t interesting to me. Nor is it interesting to most. What audiences care about are people. If you can set up a cast of characters who are interesting and put them in dramatic situations that are compelling, it doesn’t matter what the overarching storyline is. WE WILL CARE.

And that’s what Gilroy does. He opens with a flashback that introduces us to our happy main character, his happy wife, his happy best friend, and the happy teenage boy he mentors.

Immediately after making us fall in love with them, the terrorists arrive and kill Mason’s wife. I was devastated. And why? It’s just words on a page. But this is the power of good screenwriting. You create moments between characters, make us care about them, then take those characters away.

Even more brilliant? PERSONAL STAKES. What bad writers do in these scripts is they introduce a bunch of random people with random ranks who we don’t know, and expect us to give a shit if one of them is kidnapped.

What Gilroy does is he makes the kidnapped guy our main character’s best friend (PERSONAL STAKES). And who’s the kidnapper? The kid Mason mentored (PERSONAL STAKES). Everything here is personal, which makes the bonds and thus the plotlines stronger.

Gilroy doesn’t stop there. He utilizes what I’ve deemed the “mystery goal.” The mystery goal adds flavor to a goal, it adds a spike. When Mason is called upon 10 years later to go back to Beirut, he isn’t told why. It’s a MYSTERY. So you’re not just sending your character somewhere (their goal) but strengthening it with a mystery along the way. Of COURSE we’re going to want to keep reading. Just like Mason, we want to find out what the fuck they want him for.

Another key tip is to make your mystery goal IMPORTANT. Typically, when you lay down a mystery, you can keep that mystery going for 10-15 pages and the reader’s going to stay invested. People naturally will stick around until the mystery is solved. But the more IMPORTANT you make that mystery, the longer you can stretch out the reveal.

The way the CIA talks to Mason about this Beirut trip, they make it sound like a really big fucking deal. Like this is one of those things you can’t pass on. As a reader I’m going, “Ooh, this seems big time. I have to know what this is about.” If the same person had come to Mason and said, “I heard these people are sorta interested in talking to you. Maybe you should check it out.” Does that sound important enough to make you care? Of course not.

Lots of great scenes here too. Bad writers take common scenes and play them out the way they alway play out. Good writers take common scenes and they TURN THEM in a way where they play out unexpectedly. So when Mason goes to meet with the kidnappers for the first time, there are two men in masks he’s talking to. The main one, the older guy, is screaming and yelling at Mason, telling him that Mason’s going to play by their rules. After about 3 minutes of this, the other masked man calmly raises his gun and shoots the man in the back of the head for being difficult. He then takes over the negotiation.

WHAT THE FUCK?? Wasn’t expecting that.

After all this, you’re probably expecting me to give this an impressive. I was actually going higher than that at the midpoint. This was going Top 25. But then the script started doing exactly what I said you shouldn’t do at the beginning. It started focusing on the politics, the web of lies, the world of the impersonal as opposed to the personal.

One of the issues here was that Beirut had a dozen warring factions inside of it in the 80s. So there were SO MANY bad guys. So many different clubs who were part of the problem. Add onto that people double-crossing each other and after awhile, you couldn’t keep track of it anymore.

It’s the double-edged sword with these types of scripts. As they move towards their climax, they have to get bigger. But the bigger they get, the harder it is to keep track of what’s going on. So you have to either deftly calibrate how much the audience can take, or be an expert at keeping loads of information clear and easy to digest.

I eventually got lost in all the madness. And that’s too bad, cause this script had a hold on me for a big portion of its page count.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: One of the oldest writing tricks in the book. Place your hero where he least wants to be. The last place Mason wants to be after his wife was murdered there is Beirut. So where is he sent to? Beirut. You do that and I’m telling you, most of your movie will write itself.

What I learned 2: You’re never going to write the perfect screenplay. The goal is simply to do more good than bad. If you can achieve that, you’ll have a script worth reading.

For the next three months, every Thursday, I will be guiding you through writing a feature-length (110 pages) screenplay. Why are we doing this? A few reasons. For new screenwriters, it’s a chance to learn how to write a screenplay. For experienced screenwriters, it’s an opportunity to learn a different approach to writing a screenplay. And for every screenwriter, it’s an opportunity to light a fire under your ass, keep you moving, and have a finished script in your lap in just 90 days.

We have three months to achieve this, which equates to roughly 13 weeks. Each week I’m going to give you a task, which you will need to finish by the following week. I’m going to need, at minimum, two hours of your time a day. However, the more time you can contribute to the cause, the better. More time means more thought, more trial and error, more swings, which means an overall improved product.

One of the biggest pushbacks I expect to encounter in this exercise is writers saying, “Well I don’t do it that way. I do it a different way.” Tough. This is about trying something new. It’s about going outside of your comfort zone so you can grow. I don’t expect you to write every script this way from here on out. But I do expect you to discover some new methods you’ll be able to use in future scripts. So don’t complain. Just do it.

The plan is to write both a first draft and a second draft. Afterwards, the best scripts will be chosen for a tournament. You do not have to participate in the tournament if you don’t want to. It’s merely there to incentivize you throughout your journey. Those tournament scripts will be put up for critique by the Scriptshadow Faithful, who will vote for the best script each week. The feedback they give you, you can then use for further rewrites to improve your script for the later rounds.

Are we ready? Okay, let’s get to it.

First and foremost, you need a concept. We’ve been trying to come up with those for the last two weeks. Guys, I tried to get through all the loglines you sent me but there were just too many. I’ll attempt to rate a few more today but don’t hold your breath. If you didn’t get any feedback, you’ll have to go with your gut and write the idea you like best. And really, let’s be honest. You were going to write your favorite idea anyway. :)

If you didn’t participate in the last two weeks, you’ll need to come up with a concept and logline pronto. Check out last week’s post, as well as the comments, and you’ll get an idea for which concepts tend to work best. Once you’ve identified your concept, it’s time for the first task. And the first task is one that 50% of screenwriters detest. I DON’T CARE. This is your week 1 assignment.

OUTLINE AND CHARACTER BIOS

For those of you who want to start writing your script, TOUGH. Unless you’re a genius, the screenwriter who jumps into his script immediately runs out of gas by page 45. Oh, they won’t admit it. They’ll keep writing. But deep down they know they’re lost. This week’s assignment is designed to prevent that from happening.

DAYS 1-3 – THE OUTLINE

There are six main points you want to identify in your outline. But before we get to those, let’s go over the basic blueprint of a story. A protagonist is breezing along in their life. Then something happens that jolts the status quo. This thrusts them onto a journey where they try to achieve a goal. They encounter lots of obstacles and uncertainty along the way. Then, in the end, they somehow pull off the impossible and achieve their goal (or fail!).

We’re writing 110 pages here. So you’ll break your outline down into Act 1 (roughly pages 1-27), Act 2 (roughly pages 28-85), and Act 3 (roughly pages 86-110). Your scenes will average between 2 and 3 pages long. That does not mean every scene will be 2 or 3 pages. It means this is the AVERAGE. Some scenes may be 7 pages. Others may be half a page. In the end, you’ll be writing between 45-60 scenes.

The more scenes you can fill in for your outline, the better. But the only ones that are required for next week are these six. If you can figure out more, great. But these are the essentials.

The Inciting Incident (somewhere between pages 5-12) – The Inciting Incident is a fancy way of saying the “problem” that enters your main character’s life. For Raiders, that’s when the government comes to Indiana Jones and says they’ve got a PROBLEM. Hitler’s looking for the Ark of the Convenant. You, Indiana, need to find it first. Or, more recently, in The Revenant, it’s when Leo is mauled by a bear. Everything is irrevocably changed in his life after that incident.

The First Act Turn (page 25-27) – The first act turn is when your main character will start off on his journey to try and obtain whatever it is he’s trying to obtain. So what happens between the inciting incident and the first act turn? Typically, a character will resist change, resist leaving the comfort of his life. But most of the time it’s just logistics. We’ll set up what needs to happen, how they plan to do it, how impossible the task will be, etc. It all depends on the story.

The Mid-Point Twist (page 50-55) – If your story moves along predictably for too long, the reader will get bored. The Mid-Point Twist is designed to prevent that from happening. It changes the rules of the game. And there’s a bit of creativity to it. It could be an unexpected death. It could be a major betrayal. It could be a twist (Luke and Han get to Alderran, but the planet they’re going to has disappeared!). The point of the Mid-Point Twist is throw your story’s planet off its axis.

The End of the Second Act (page 85-90) – This will be your main character’s lowest point. They likely just tried to defeat the villain or the problem and failed miserably. Along with this, everything else in your character’s life should be failing. Relationships. Their job. Their family. It’s all falling apart. Your hero will be AT HIS LOWEST POINT. Hey. HEY! Stop crying, dude. It’s just a movie. He’s going to get back up and kick ass in the third act. But right now, it looks like he’s fucked.

The Early Second Act Twist (page 45) – We’re going backwards here only because I wanted to get the important plot points down first. Once you have those, figure out page 45. Basically, page 45 will be 15-20 pages into your second act, typically where most writers start running out of ideas. You need to add some sort of unexpected moment here. Something that lights a fire under your plot. It’s not going to be as big as the Mid-Point Twist. But you can’t have 30 straight pages of the same pacing. You have to mix it up. The Early Second Act Twist in The Force Awakens occurs when Rey and Finn get captured by Han Solo. Notice how Han’s entrance into the story takes everything in a different direction.

The Late Second Act Twist (page 70) – This is the same idea as all the other “twists” we’ve been talking about. If you mosey along for too long without anything new or different happening, the reader gets bored. You need to be ahead of the reader, always coming up with plot points that they didn’t expect. I’ve seen writers use The Late Second Act Twist to kill off a character. In Frozen, it’s the moment where Hans reveals to Anna that his entire courting of her was a sham designed to take over her kingdom.

Once you have these six key moments in the script mapped out, you’re in great shape. Why? Because now you always know where you’re going. You always know where you’re sending your characters, which will give your script PURPOSE, something people who write randomly and without an outline rarely have. And don’t worry. These moments are not set in stone. As you write the script, you’ll have new ideas, and these key points may change. That’s fine. But by having something in place initially, you’ll be able to write a lot faster.

It should also be noted that not every story will follow this path. Not every script’s structure is based off of Raiders of The Lost Ark. I get that. Still, you want to think of these moments in a script as CHECKPOINTS. Whether you’re writing the next Star Wars or the next Magnolia, every 15-20 pages, something needs to happen to stir the pot. So if you’re going to take on something unique, no need to fret. Give yourself those 6 checkpoints so that your script is moving towards something.

DAYS 4-7 – CHARACTER BIOS

I know. You HATE CHARACTER BIOS. Look at it this way. Remember when your parents told you to eat your vegetables but you never understand why when Captain Crunch and pop tarts tasted so much better? Then when you hit adulthood and you were 40 pounds overweight, you looked back and thought, “Hmm, mom and dad may have been right about that one.” Well, the same thing’s going on here. Character bios may not be fun. But you’ll thank me for them later.

What you’re going to do is write a character bio every day for your four biggest characters. One of those characters will likely be your villain. Here are the things I want you to include in each bio. Try to get between 1500-2500 words for each character.

1) Their flaw – Figure out what’s holding your character back at this moment in their life, the thing that’s keeping them from reaching their full potential as a human being. Stick with popular relatable themes. Selfishness, egotistical, stubbornness, fear of putting themselves out there, doesn’t believe in themselves. You may not explore this flaw in the movie. But it’s good to know, as it will be the main thing that defines your character.

2) Where they were born – A lawyer from the projects in Chicago is going to talk and act differently than a lawyer from the upper crust of a rich East Coast suburb.

3) What their family life was/is like – Our relationships with our siblings, but in particular, our mother and father, influences our personality and approach to life more than anything else. Know your character’s relationship with each and every family member.

4) Their school history – Were they a nerd? The popular kid? A drug dealer? An athlete. Our school experience, particularly high school, affects who we are and how we act for the rest of our lives. So the more you know about this period in your character’s life, the better.

5) Their work history – Work is 50% of our lives (for many of us, a lot more). It has a big effect on who we are. So you want to establish what your character used to do before they got their current job, and also the events that led to them getting their current job.

6) Highlights of their life – This is basically everything else, the character’s highlight reel, if it were. When they lost their virginity, any devastting breakups, their highest points, their lowest points. Just let loose here and use this section to discover what your character’s life has been like.

And that’s it! You’ve completed your weekly task. If you finish ahead of time, go back to your outline and fill in the areas between the major plot points. The more scenes you can outline ahead of time, and the more detail you can add to those scenes, the easier it will be to write the script when that time comes. Okay, all of this starts RIGHT NOW. So what are you waiting for???