Search Results for: F word

Get Your Script Reviewed On Scriptshadow!: To submit your script for an Amateur Review, send in a PDF of your script, along with the title, genre, logline, and finally, something interesting about yourself and/or your script that you’d like us to post along with the script if reviewed. Use my submission address please: Carsonreeves3@gmail.com. Remember that your script will be posted. If you’re nervous about the effects of a bad review, feel free to use an alias name and/or title. It’s a good idea to resubmit every couple of weeks so your submission stays near the top.

Genre: Comedy

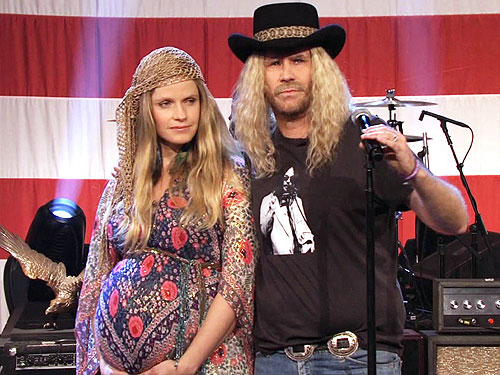

Premise (from writer): Two brothers-in-law who hate each other must get along when their wives become pregnant and the couples are forced to move in together to save money before the babies arrive.

Why You Should Read (from writer): Having this kid is expensive. More than I even calculated for. And believe me, I calculated. I wonder if there is a simple solution to cut costs and release the worry and anxiety I feel about making all this work. My wife suggested moving in with her sister and her husband during the pregnancy. Smart. But I don’t care for that guy. Can’t stand going to dinner with him. Living with him for nine months? Nah. But my wife. My wife is persistent and she makes a good case. What if we all moved in? What if…

Writer: Emmitt Webb

Details: 104 pages

So I’ve come across “Pregnant Pals” a few times when picking Amateur Offerings scripts, and I’ve always passed over it. Why? To be honest, it felt contrived. I have trouble getting on board with the idea that two people who hate each other’s guts would willingly move in together. Even if you bring the wives into the equation. What wife, wanting her first pregnancy to go as smooth as possible, would bring into her home two warring husbands? It doesn’t feel realistic.

With that said, it’s a comedy. And comedies don’t have to make as much sense as other genres. So when Pregnant Pals won a spot in Amateur Offerings via “Random Picks” Week and then edged past the competition on a day when most people were focused on finishing their SS250 scripts before the deadline, I threw my preconceived notions to the curb and put my hope in the power of pregnancy.

So the plot is pretty much identical to the logline. On the one side we have Pete and Katie Gurley. Pete’s a super-confident guy who’s pumped that he just got his wife pregnant. On the other side we have Langford and Darla Winston. Langford’s a wet blanket serious type. And Darla is Katie’s sister. It just so happens that on the very same day, Langford got Darla pregnant.

What could be better than two sisters with the same due date, right?

Well, there’s a problem. Pete and Langford hate each other. Like more than Donald Trump and Mexico hate each other. And that wouldn’t be a problem except for that Langford just ran out of money, which means he can’t support his family.

Darla hints about their financial woes to Katie, and the next thing you know, Katie asks if they’d like to live with her and Pete during their pregnancy. Pete and Langford are strongly opposed to this, but when the wives insist on it, they have no choice. What follows is 9 months of a lot of anger, conflict, frustration, and, of course, shenanigans.

It took me awhile to understand what kind of movie I was reading here. At around page 40, I got it. This is Stepbrothers, the unofficial sequel. And when you look at it that way, you can kind of see it working. Because Stepbrothers wasn’t a movie that really worked on paper. It was an overly simplistic idea that got the perfect actors to play the two main parts.

So if this was cast well, maybe the things I’m about to say don’t matter as much. But I always subscribe to the theory, “Fulfill the potential of your script yourself. Don’t hope others see the potential and fulfill it for you.” To that end, there are some issues that need to be addressed here.

Let’s start with the first two scenes in the script. Both scenes are sex scenes between our main couples where the sisters get pregnant. In the first scene, Pete looks for positive reinforcement from Katie after the sex. It’s a chipper fun scene. I don’t have any complaints. However, in the very next scene, after Langford and Darla finish their sex, Langford ALSO looks for reinforcement about his performance.

Now their approach in seeking reinforcement is different, but this is the key moment in the story where you want to establish just how different your two main characters are. These are the characters who are going to be driving the conflict throughout the screenplay. By showing them essentially acting the same way, you’re telling the reader they’re similar. When you’re writing comedies, this moment needs to show how extreme the differences are between the characters.

The next issue was dialogue. I never got the sense that Emmitt obsessed over the dialogue. Partly because the jokes weren’t as clever as they could be, and partly because a lot of lines contained mistakes. Take this exchange between Pete and Katie. In it, Pete doesn’t want to have dinner with Langston and Darla: “I’ll give you one thousand dollars if I don’t have to attend tonight,” Pete pleads. Katie replies: “You don’t have one thousand dollars to bet.” This exchange doesn’t make sense. Pete never brought up betting. He said he’d GIVE Katie a thousand dollars. It’s a small thing but it’s a red flag. As a reader, I’m now, in the back of my mind, wondering if the writer has the chops to write good dialogue.

Later in the screenplay, there’s a scene where Katie forces Pete to text Langford. Langford gets the text, but doesn’t know who it is, so he asks. Pete writes back: “It’s Pete.” “Who?” Langford replies. “You mean whom?” Pete shoots back. The problem with this exchange isn’t the exchange itself. It’s that Emmitt would constantly misuse “your” and “you’re” throughout the screenplay. How can I trust characters correcting characters’ grammar when the writer himself can’t use the correct words?

And then there are basic lines of dialogue, like, “I don’t see what’s your issue with him,” which literally reads out as, “I don’t see what is your issue with him.” By itself, a reader can forgive this. When it’s surrounded by other dialogue issues, however, it becomes one more piece to add to the “Can I start skimming now?” puzzle.

And this is a script built around dialogue. It’s going for that quippy rom-com or bro-com fire-back-and-forth dialogue. In these types of scripts, you can be a little weak in the concept department. You can be a little weak in the plotting department. But the one area you can’t be weak in is the dialogue department. That department is your star. Under that reality, lines like, “I don’t see what is your issue with him” become script-killers.

If I were giving notes on this as an executive hoping to get the studio excited about the project, I’d come up with a setup that was much less convoluted. Have Pete and Katie living the dream. They just bought a new house, they’re successful, they got pregnant. They’re at the pinnacle of their lives. Use the first few scenes to establish that.

Scene four, the doorbell rings. It’s Katie’s long-lost estranged sister and her deadbeat boyfriend/husband (he refuses to use “labels”). They ran out of money. This is the only place they had to come to. Katie can’t turn her sister away. Of course she lets them stay. Of course, one week turns into two, two to four, etc.

In this new version, it’s not just Pete and Langford who have issues with each other (they’re from two completely different worlds), but also Katie and her sister, who need to resolve some life-long issues. They’re also both pregnant, which complicates matters. But the experience ends up bonding them, and everyone leaves happy.

Doing it this way would also allow you to do more with the story. One of the problems with the script now is that the husbands already hate each other when they move in. So there aren’t a whole lot of places to go with that. If the husbands didn’t even know each other, then the script starts off with them trying to make it work, realizing they come from two different worlds, going to outright hatred, eventually finding common ground, and finally becoming friends. In other words, there’s more of an ARC to the storyline, which tends to be more pleasing from a storytelling perspective.

But the point is, I think the setup here is more complicated than it needs to be. Simplify it. The great thing about Step-Brothers is how invisible the setup is. Right now, the setup for Pregnant Pals is one of the most convoluted I’ve seen all year! And like I always say: Convoluted is evil. Destroy all convolutedness!

Script link: Pregnant Pals

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: I find that writers needlessly overcomplicate concepts or plots to the point where they’re so convoluted, they don’t make sense. Always take a step back and look for ways to simplify the concept. If there’s one thing I’ve learned about screenwriting over the years, it’s that the simplest solution is usually the best one.

I’ve talked about this scene on the site before, but no matter how many times I write about it, I can’t get it out of my mind. To me, it represents everything that was wrong with the two Matrix sequels and every bad writing choice that could have possibly been made in a single scene. So I wanted you to watch the scene for yourself, then I’ll break down everything that’s wrong with it (there’s a lot) so that you never make the same mistakes in your work. Here we go. Are you ready? (I apologize for the badly synced Youtube video but it’s the only one I could find).

1) We don’t have any idea who this other character is – Outside of some vague reference of this old dude being important to the city, we have no idea who he is. If we know zero about a character in a scene, we’re probably not going to give a shit about what he says. And let me make clear that the main reason we don’t know who he is is because the Wachowskis do a terrible (lazy) job of setting him up. Set up your characters clearly so we know and understand what they’re about.

2) There is ZERO conflict in the scene – Outside of a couple of minor misunderstandings, this may be the most conflict-free scene ever written. It is so devoid of any drama that it is the embodiment of boredom. Always try to include conflict in every scene!

3) Philosophizing – This one gets me in trouble but I’ll continue to spread its message. Don’t have your characters philosophizing about things. It’s just boring to listen to unless you have an extremely unique view of the world and you’re a borderline genius with insight into things that nobody’s ever thought of before. Which neither of these two have. (While I didn’t like True Detective, I admit that Rust Cohle’s philosophizing would fall under the ‘good’ category)

4) Characters need goals in scenes – Scenes always work better when every character in the scene is trying to get something (or one’s trying to get, and the other’s trying to resist). Neither of these two characters are trying to get anything. They’re just leisurely talking about their shitty living arrangements. Compare this scene to the one in the original Matrix where Agent Smith philosophizes about how humans are a virus. Yes, I said “philosophizing.” Something I just told you not to do. Ah, but the big difference? AGENT SMITH WANTED SOMETHING (A GOAL) FROM MORPHEUS. He wanted the codes. He was trying to break him down. So the philosophizing a) was placed before an important moment and therefore we were willing to wait for that moment, and b) had a plot purpose. The closest thing to a goal in this scene is that Boring Old Guy likes water.

5) Zero suspense – It’s as if The Wachowskis forgot what suspense is in this movie. Look at the scene from the original film where Neo is going to see the Oracle. In that scene, we have what could be construed as a ‘boring” scene when Neo is stuck in a room with a bunch of child prodigies. The difference there was that the Oracle had been built up as this extremely important character who was going to give us incredibly important information (tell Neo whether he was “The One” or not). When you build something up that’s going to be anticipated by the audience (code word: suspense), then you can slip in exposition and philosophizing and backstory in the meantime, due to us being so eager to see what you promised us. When you don’t promise us anything, however, you get scenes like this, that just sit there.

6) Characters standing around – Characters standing or sitting around is usually the most boring way to present a scene possible and should be avoided at all costs. Instead, have your characters chatting on their way to something important – a goal they’re trying to achieve. If they’re not walking somewhere, have it so one of the characters has to be somewhere soon, and therefore must leave at any moment (which is the perfect segue into our next problem).

7) No scene agitator – There’s nothing agitating this scene. It sits there, unimpeded, allowed to be its boring self. Get someone out there (an “agitator”) that says they need Neo right now, so we feel a sense of tension in the scene, that they must finish this talk quickly. This will also create suspense, as the audience will be wondering, “Ooh, why is Neo being called away?”

8) Sloppily executed – Notice how we go from one boring standing talking scene TO ANOTHER ONE WITH THE EXACT SAME CHARACTERS. Your job as a screenwriter is to make things as seamless as possible. If they wanted Neo and this Councilor guy to look out at the inner workings of the city, for God’s sake, start them there instead of creating this awkward, “Let’s go take a look at the inner workings of the city, are you up for it?” transition moment. I mean would it have been that hard to start with Neo already on the lower level overlooking the city?

9) Dialogue that tells us things WE ALREADY KNOW – “These machines are keeping us alive while other machines are trying to kill us.” Jeez, Captain Duh, thanks for pointing that out. In general, never repeat things the audience already knows unless it’s a really important plot point that they might forget otherwise.

10) Scene didn’t need to exist in the first place – This is the biggest faux pas of them all. You should only include a scene if it pushes the story forward. How does this scene get our characters any closer to defeating the agents or preparing for the invasion of their city? It doesn’t. And therefore, it should’ve never been included.

Is “Billions” Showtime’s answer to “House of Cards?” It sure seems that way. So how does it stack up? Should Frank Underwood be worried?

Genre: TV Pilot/Drama

Premise: A New York City Attorney attempts to take down one of the richest and most beloved men in New York.

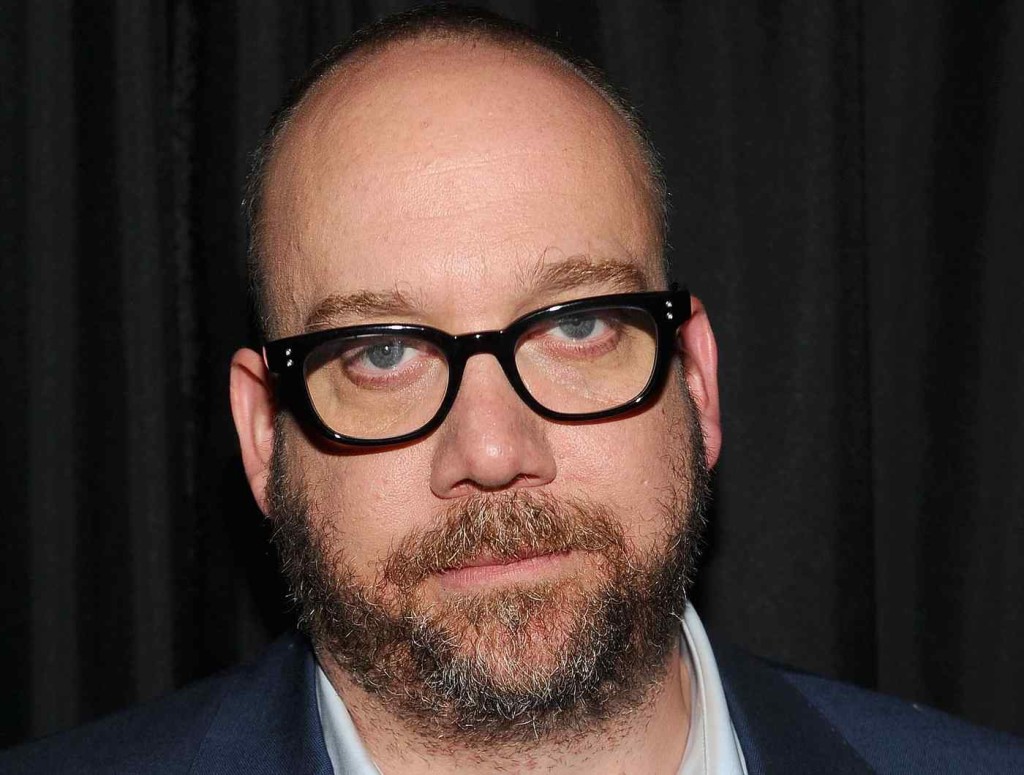

About: Billions has been building buzz for a few months now in anticipation of its late year launch on Showtime, which is quietly becoming a force in an increasingly competitive TV landscape. With Homeland, Ray Donovan, The Affair, and Masters of Sex, the longtime cable mainstay is even starting to make HBO sweat. The show has a stellar cast that includes Paul Giamatti, Damian Lewis, and Malin Ackerman. It’s written by Ocean’s 13 writers Brian Koppleman and David Levien, as well as Andrew Ross Sorkin, who’s the co-host of CNBC’s Squawk Box, whatever the hell that is.

Writer: Brian Koppleman & David Levien & Andrew Ross Sorkin

Details: 62 pages – Draft 1.5

So before I get into Billions, I want to share with you a little LA secret. When you come to LA on vacation… THERE’S NOTHING TO DO HERE. Nothing. One of the saddest things I see is tourists wandering around the concrete jungle that is Sunset Boulevard and La Brea, looking for something, ANYTHING to do.

But there’s nothing.

Disney Land? It’s Disney World’s pathetic little brother. The beach? It’s polluted. Famous restaurants? Try New York. Rodeo Drive? See how much fun steps are for more than 30 seconds. There is nowhere to go here and seeing the heartbroken tourists’ faces when they realize this is the case is heartbreaking in itself.

So I’m going to give you somewhere to go. Are you ready? Roscoe’s Chicken and Waffles. I don’t know what kind of batter crack concoction they mix into their waffles and chicken, but when you go there, order both, and prepare to have a carnival in your tonsils. There are a few locations. I recommend the one on Pico, as that’s the only one I’ve been to. It’s great. And when you’re finished, just get on a plane and go home. There’s honestly nothing left to do.

And if you want to know what this has to do with Billions, well, if I were at Roscoe’s right now, I’d order a billion waffles. And so would an uncomfortable Paul Giamatti. They’re that good.

I’m not sure Bobby Axelrod would join us though. The 40-something’s 20-something physique seems very anti-waffle. The discipline of not dipping one’s fried chicken in syrup is the same discipline that’s likely made him a billionaire.

Across town (that town being New York City), Chuck Rhodes, the U.S. attorney to the Southern District of New York, is planning Axelrod’s demise. While the office doesn’t have any hard proof, all arrows point to Axelrod doing some not-so-savory financial naughtiness to build his company.

Here’s the problem though. Axelrod is beloved in New York. It’s made very clear that if Chuck goes after him and fails? He’ll be lucky to get a job at Roscoe’s Chicken and Waffles on Pico. That’s how these power plays go down. If you go after someone and it doesn’t work out? Pack your bags, baby. And get ready to suck syrup.

And really, there isn’t much that happens in this pilot other than setting up that impending conflict. There’s also an overtly-manufactured storyline where Chuck’s wife works as the in-house psychologist at Axelrod’s company (how convenient for the story!) as well as some periphery players like an SEC lackey who wants Chuck to go after Axelrod and then swoop in and take all the credit. But for the most part, this is one big setup for the fun that will go down in future episodes.

Here’s a nice little tip for a lot of aspiring screenwriters out there. If you’re having trouble coming up with an idea for a movie/show? Or you want to juice up your current script, which feels kind of weak? Look to money. Outside of love, money is the most universally understood thing in the world. A 40 year-old billionaire in New York City understands the value of it. A 5 year-old homeless boy in Somalia understands the value of it.

So if you build a story around money – the need for more of it, the desire to steal it, the problems that come with it – at the very least, you’re going to have the core of something compelling.

And Billions taps into that. What we get from this pilot is that a war that revolves around moola is about to go down. And that’s exciting. I like wars!

But Billions may have forgotten about one of the unwritten rules of screenwriting. And that’s that extremely rich protagonists aren’t sympathetic, aren’t relatable, and are generally disliked. Unless you make them likable in other ways. But our co-protagonist here, Barry Axelrod, starts out the story answering the question: “Chopper’s waiting. We’re gonna be late,” with “How am I late when it’s my fucking chopper.”

Already, I’m not really into this guy. Even when we find out he sends kids to college based on a fund he built after his company was destroyed in September 11, he doesn’t seem happy to do it. In fact, he seems miserable.

In the show that Billions is trying to be, House of Cards, that pilot opens up with our main character, Frank Underwood, getting fucked over. He was promised a prominent position in the White House for his support during the campaign, and when the president won, he went back on his word and discarded Frank.

So even though Frank became a scheming manipulator, we were on his side. We saw these people screw him over. So we wanted him to even the score. It’s very subtle differences in screenplays like this that can have a huge impact on the story.

Another problem with Billions is that it’s very inside-baseball. And I love that they brought in the Squawk Box dude to help with the authenticity of the story. But they go so far with it that, at a certain point, I couldn’t relate to what was happening at all. Big guys with lots of money trying to screw over other guys with lots of money. Who am I siding with here?

The US attorney? He’s kind of a hard-ass dick. So again, that’s one more character I’m not relating to. The one character who sticks out is Dr. Mojo, the psychologist at Axelrod’s company. The character’s written as this female alpha-dog who doesn’t just give her thoughts on feelings, but tells her money-hungry clientele what to buy, what to sell, what to get rid of.

I’d never seen that character before and it reminded me how important it is to look at each character you’ve written and ask, “Am I writing this character the exact same way everyone else is?” Usually when I see a psychologist, she’s calm, soothing, there to bring out exposition from the other character. For once, we got less of “How does that make you feel” and more of “You need to do this, this and this.”

But I think the biggest Billions Blunder is that it doesn’t tap into the one thing that an audience wants out of a show like this – they want the poor to finally take down the rich, the rich who have been taking advantage of the poor for centuries. There are no poor people represented here. Just politicians trying to eliminate Axelrod. And it’s not even because they think what he’s doing is wrong. They just want to use the political clout gained from eliminating him to further their career.

When you add up all these issues to a script that feels drier than a Roscoe’s waffle that’s been left in the sun all day, you get a show with an uncertain future. With that said, I know they’re putting a lot of resources into this show. They really want it to work. So hopefully they’ve figured some of these issues out in the interim.

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Billions failed to answer a critical question all screenwriters need to ask themselves at the beginning of their story. Who is it the audience is going to root for? If you don’t have a clear answer to that question, you’re gonna be in trouble. Because if we have nobody to root for in a story that’s conceivably going to go on for 75-100 hours, we’re probably going to tune out pretty quick. I’ve heard Vince Gilligan talk about how worried he was that nobody would want to root for a guy who made and sold meth. But Walter White’s family needed him. Without that money, they were screwed. So of course we wanted him to succeed. What he was doing, he was doing for a good cause. There’s nothing like that here.

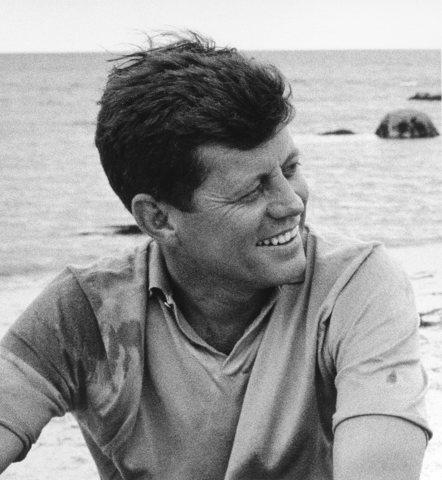

Genre: War/Period/Real-life story

Premise: The story of how a young World War 2 Navy commander saved a group of men after their ship was destroyed by the Japanese. That man? John F. Kennedy.

About: This script made a lot of noise a few months ago and will probably end up pretty high on this year’s Black List. Although the script went into just about every major production company in town, there hasn’t been any mention of a sale yet. Should it indeed finish high on the Black List though, expect that to change. Co-writer Evan Kilgore is a novelist with 4 books to his name and his writing partner, Samuel Franco, executive produced 2014’s small indie film, Affuenza. In other words, Hollywood had no idea who these guys were. Well, they know now!

Writers: Samuel Franco & Evan Kilgore

Details: 117 pages (5/4/15 draft)

I have to give it to Franco and Kilgore (that sounds strangely like a 1930s comedy duo). They may have discovered the most genius idea ever. First off, what are movies about? They’re about heroes. And what bigger hero is there than John F. Kennedy? So already, this writing team has tapped into an extremely marketable character.

But wait, there’s more!

The problem with JFK is that all his stories have been told. Or at least, THAT’S WHAT WE THOUGHT! Franco and Kilgore discovered this long forgotten heroic war story of JFK’s. And guess when that story takes place? World War 2. World War 2 is one of the easiest subject matters to market in the movie industry.

So let’s recap. We’ve got…

1) One of the greatest heroes in American history.

2) A little-known heroic story from his past.

3) A World War 2 setting.

As they’d say on Seinfeld: “It’s gold, Jerry! Gold!” However, there’s this strange Dallasian cloud hanging over this project. Despite having all these elements in place, despite it going into every territory in town, it didn’t sell. What does that mean? Could it be that the script’s bad? That’s what was on my mind when I picked Mayday 109 up. Let’s see if we can get a better understanding of what went on here.

JFK was a kid with way too many health problems. He was supposed to die numerous times growing up, but he always seemed to fight his way through it. And if there’s anything this first act is about, it’s about how JFK never stops fighting.

At Harvard, he competes in the Swimming Championships despite having a 101 fever. When his older brother, Joe, throws it in his face that he’s not up to snuff, JFK challenges him to a sailboat race. Despite never having beat his bro before, he does it this time. JFK don’t give up and don’t back down. Betta ask somebody.

Cut to the Japanese bombing Pearl Harbor and JFK wants to go to war, something his father is against. JFK goes anyway and within a few years becomes the Captain of a Patrol boat. This doesn’t sit well with the crew, who believe it’s the Kennedy name that got him the position, not his actual ability.

Before he can dissolve that tension, their ship is rammed into by a giant Japanese destroyer. His men are scattered everywhere and somehow JFK is able to save 10 of the 12 crew, getting them over to a nearby patch of land.

From there, the group must make a tough decision. Do they try and swim to a nearby island that gives them a better chance at contacting help? Or stay here and wait for someone to pick them up, a decision that could end with the Japs finding them first.

Kennedy convinces the reluctant group to swim, and that begins an island-hopping adventure where Kennedy swims from island to island looking for friendlies. Eventually, he finds some locals, carves a “help” message into a coconut, and has them travel to a nearby base. This coconut would later become famous, as it’s one of the reasons Kennedy was able to become president of the United States.

The cool thing about writing a true story is that everything’s all plotted out for you. Sure, you need to cut some things and move other things around, and maybe even get creative with the order in which the story is told. But if you’ve found a good real-life story, you have what all screenwriters dream of – a defacto outline ready to go.

Mayday 109 has that. After the crash, you’ve got that strong goal (get to safety). The stakes are high (Japanese boats heavily patrol the area), the urgency is there (they have no food, no water. If they don’t find a solution soon, they die). And yet something’s missing. What it is, I’m not sure.

My initial instinct is that the story’s too chaotic. It doesn’t have the proper structure in place to take advantage of the dramatic problem. I’m reminded of another boat wreck movie, Titanic. One of the reasons James Cameron’s movie worked so well was because he designed his story to milk the tension, to milk the suspense.

The Titanic doesn’t just hit an iceberg and go down 2 minutes later. That would’ve been chaotic and crazy, but it would’ve been over within 2 minutes! Instead, they hit the iceberg and there’s this realization that the ship is going down, but it’s going to take a couple of hours. This means that everything that happens from that point on, even basic conversations, are going to have an undercurrent of suspense to them. Because we know the end is coming. And everyone’s running out of options as far as what to do.

Here in Mayday, it doesn’t feel like that kind of thought – the kind that maximizes the suspense – has been put into this. There’s more of a “moment-to-moment” approach, where we’re simply trying to solve immediate problems (Should we swim to the next island? Yes or no?). And while that kind of storytelling is perfectly valid, it can become exhausting.

And repetitive too. The script is pretty much about Kennedy swimming. A lot. If I’m being honest, I got sick of that. And that’s supposed to be the core of where the story’s excitement comes from.

Finally, I feel like the character stuff was a bit on the nose, specifically JFK’s relationship with his father. We never go beyond the basic, “Dad doesn’t believe in me” stuff, and it kept the script from really resonating on a deeper level. For example, we get lines like JFK saying to his dad, “Just once believe in me the way you believe in Joe.” That line can work if the rest of the dialogue is deftly written. But if the rest of the dialogue feels surface-level and on-the-nose, lines like this stick out as a problem.

As I’ve said to you guys before, the key to making a script really resonate with the reader is to do so on the character front. You can have a wild captivating story like this one. But if you don’t create a couple of fascinating relationships within the chaos that need to be resolved, each which strike to the core of who your characters are and what their problems are, the story will sink.

Not to get all James Cameron on you. But Rose from Titanic is the perfect example of this. She was trapped in a life that prevented her from being who she wanted to be. Her relationship with her fiancé represented this. So when she finally broke away from that, it was emotionally cathartic for the audience. There’s an attempt to do something similar here with JFK and an ensign who doesn’t like him, but again, it happens mostly on the surface.

And I don’t want to be too down on the script. It’s not a bad screenplay. I think there’s just an element to the story that hasn’t been realized yet. I hope the writers figure out what that is, because if they do, I could easily see someone like Robert Zemeckis coming on and directing this. It seems like it’s right up his current wheelhouse.

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: I am hereby limiting ALL SCREENWRITERS to only THIRTY DASHES (outside of sluglines) in each screenplay they write. NOT A DASH MORE! The overuse of this inorganic-looking character can quickly make a screenplay look like a technical document. Remember, the uglified formatting of a screenplay ALREADY makes it look too technical. You don’t want to add anything that’s going to accentuate that. If I were to estimate how many times the dash was used in Mayday 109, I’d say easily in the neighborhood of 1500 times. It really killed the look and flow of the script.

Get Your Script Reviewed On Scriptshadow!: To submit your script for an Amateur Review, send in a PDF of your script, along with the title, genre, logline, and finally, something interesting about yourself and/or your script that you’d like us to post along with the script if reviewed. Use my submission address please: Carsonreeves3@gmail.com. Remember that your script will be posted. If you’re nervous about the effects of a bad review, feel free to use an alias name and/or title. It’s a good idea to resubmit every couple of weeks so your submission stays near the top.

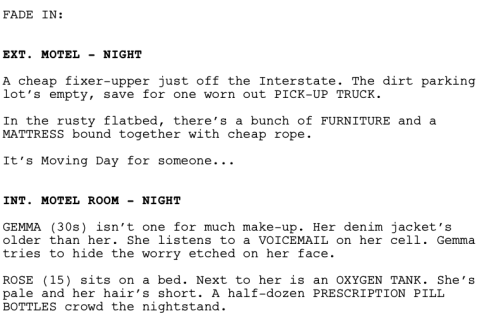

Genre: Thriller/Lifetime (Made-For-TV)

Premise (from writer): When her homecoming ends in tragedy, a desperate single mother spins a web of lies to protect the family nursery from a ruthless property developer.

Why You Should Read (from writer): Breaking into the industry through Lifetime MoW (Movie of the Week) means is legit. Many writers have started out there and transitioned into feature films. It’s a subject we’ve never covered on Scriptshadow in my 4 years there. We’re always focused on high concept studio-oriented stuff. Why not made-for-TV? That career path would make for an interesting discussion in your blog.

Writer: Brett Martin (Electric Dreamer)

Details: 105 pages (note: This is an updated draft from the one posted on Amateur Offerings) – Edit: I’ve been informed that I read the OLD draft. Take that into consideration when reading the review. Sorry about that, Brett!

Long-time commenter and awesome community member, Electric Dreamer, has bestowed upon the Scriptshadow community a challenge heretofore unknown to the reader faithful. To review a made-for-TV screenplay.

We talk about genre scripts and Oscar hopefuls and giant spec sales all the time, ignoring the fact that there’s a huge industry that exists below the line where writers make a living on, let’s just be honest here, guilty pleasure TV flicks. “The Day Janie Left” doesn’t just write itself, you know.

So I thought today’s review could double as primer for the made-for-TV world. If you want to play in the sandbox where the sand isn’t as deep, where you can develop your skills before moving up to the big leagues, then Made-For-TV might be for you. Let’s check out Electric’s “Reap What You Sow” to see what these films are all about.

30-something Gemma has just arrived back in her home town with her 15 year old cancer-stricken daughter, Rose. The two are flat broke and from the bits and pieces of their conversation we’re privy to, it sounds like Gemma is hoping to reconnect with her father, possibly even stay with him, a difficult decision since he’s always been an abusive alcoholic.

But when Gemma shows up at her childhood home, her father is dead, his neck pierced with a broken whiskey bottle. It would appear that he had a drunken accident.

OR DID HE???

When studly Sheriff and former Gemma boyfriend Carl Baxter comes to take a look at the mess, he’s not convinced that this was an accident. In fact, he’s suspicious of the fresh bruises that have appeared around Gemma’s neck.

COULD GEMMA HAVE MURDERED HER FATHER???

While Carl turns the dad’s death into an official murder investigation, Gemma learns that the richest man in town, Walt Sharpe, was just about to close a deal to buy Gemma’s house. It doesn’t take Gemma long to realize that Sharpe wants to build some giant resort, and that her father’s house is right in the middle of it.

Apparently, when the dad died, the contract disappeared. So Walt employs his right hand man, Butch Garner, to form a relationship with Gemma, allowing him access to the house where he might possibly locate this missing contract.

But then Butch starts to actually like Gemma, and everything gets redonkulous. This forces the increasingly psychotic Walt to try and get the house through other means. And through that pursuit, we learn the shocking truth behind who killed Gemma’s father.

Okay, I’m going to start off with some advice right out of the gate. Brett sent me a new version of his script, in which he says he completely rewrote the first 12 pages. I COULD TELL. And this is why I warn writers away from doing massive changes at the last second.

Screenplays are odd beasts. They don’t operate under the known laws of physics. You can look at a change you just made and think, “Wow, I really nailed that. That’s so much better than what I had before.” Then you pick up your script a week later, read the same scene, and it’s like a mentally challenged fifth grader hijacked your script.

What happened?

What happened was TIME. Time allows perspective. When you rush, you don’t have perspective. You can’t see how the changes fit into the larger picture yet.

That’s clearly what happened here because once the script got going, it was fine. It was only the first few scenes that had me confused. For example, here’s the first half-page.

So we’re at a motel. Then we’re told of furniture and a mattress outside and that “It’s Moving Day for someone…” Is this an off-the-cuff description to add color to the writing? Or is this referring to specific character(s) we’re about to meet?

This early in a script, before you’ve identified the style or voice of the writer, you have to assume that everything is being written with a purpose. Therefore, I’ll assume the “moving” has to do with our characters (Gemma and Rose). But if it’s “moving day,” why aren’t they moving from their home? Why are we at a motel?

Maybe they’re in the process of moving? Like they’re on one leg of the journey? Except in the scenes that follow, there’s no actual moving that occurs. The point is, I’m stuck trying to figure something out that should be obvious. And I believe this mistake was made because of rushed writing.

I point this out in my book as one of my tips. Don’t make a lot of changes right before you send your script out. Something’s bound to get screwed up.

Moving on. Reap What You Sow is a very tight story. One thing I’ve realized about the Lifetime/Hallmark movies is that because they embrace formula so openly, they’re perfect for the GSU (Goal, Stakes, Urgency) approach. These movies DESPERATELY want you to use this formula. And they don’t care if it’s transparent.

So here Gemma has a goal – she has to get her late father’s garden/landscaping business up and running to secure the house. The stakes are if she fails, she loses the house. And the urgency is that she only has a month to do it or else Walt gets the home.

But Brett didn’t stop there. Brett use something I like to call GSU-squared (or even GSU-cubed). This is when you give GSU to EVERY SINGLE MAJOR CHARACTER IN YOUR SCRIPT.

So we know Gemma’s GSU plight. But we also have Walt’s. His goal is to get the house from Gemma. The stakes are that if he fails, he can’t build his super-resort. And the urgency is the same time frame that Gemma’s got (since they’re working off the same ticking time bomb – one month).

Then you have Butch. Butch’s goal is to find the contract. The stakes are his standing in Walt’s company. And the urgency is the same (1 month).

By giving every character GSU, your script is always MOVING. Whenever we cut to a character, they have something they’re trying to achieve. And because of “S” (stakes), that something is always important.

If you’ve ever found yourself cutting to characters and they feel boring or static, chances are it’s because they don’t have a goal, or there are no stakes attached to their goal, or there’s no time constraint involved in their journey. Give a character GSU and they instantly come alive.

So Brett did a really good job there.

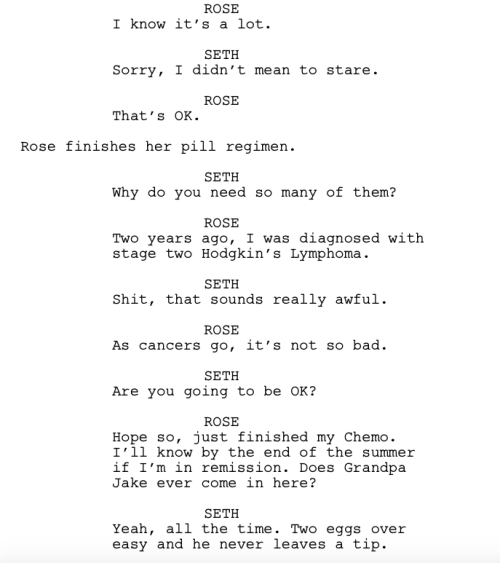

But where Reap What You Sow runs into problems is in its dialogue. And maybe this is because I don’t understand the expectations for dialogue in made-for-TV movies (the extent of my made-for-TV watching is limited to Mommy Dearest), but whether their expectations are low or not, there wasn’t enough LIFE in these words. Here’s a sampling from a scene in which Rose’s new crush, Seth, stares at her oxygen get-up.

It felt like dialogue. It never felt like people talking. And I think that’s because Brett didn’t know his characters well enough. Rose, in particular, seemed like she was only there to add financial strife to Gemma’s situation. I never saw her as a real person. And when you don’t get to know your characters, you don’t learn their little idiosyncrices, their fears and reservations – the things that inform how a person speaks.

For example, I read a script not long ago where a meathead character would pepper his speech with “you know” every five seconds, even when he didn’t need to. Or, to compare similar characters, there’s the character of Emma in the TV show, The Bates Motel. Like Rose, she needs a breathing apparatus.

Emma is infatuated with Norman, so every part of the way she speaks is geared towards pleasing him, impressing him, trying to get him to notice her. There’s a neediness to her speech pattern that brings her dialogue alive. Here in “Reap What You Sow,” characters speak mainly to move plot along or give opinions about things (i.e. “I don’t like Butch.”). There’s a lack of naturalism and a lack of fun to the dialogue.

And I don’t think this being a TV movie should be an excuse to write less-interesting dialogue. Sure, the dialogue’s probably going to be more on-the-nose than in, say, a David Fincher film, but you should still try to be on-the-nose with some flair.

I guess the best way to sum up my reaction to the dialogue here is that it felt like Brett was bored writing it. I want him to write a version where it feels like he’s having fun. And isn’t that what Lifetime wants anyway? Don’t they want a little cheese? A little goofiness? A little flash?

It’s nearly impossible for me to give a rating here because I’m trying to rate something that embraces a lower quality product. And while I definitely thought there was a lot to celebrate, the story wasn’t challenging enough to keep me engaged. That and the dialogue were what kept this from being “worth the read.”

With that said, I feel like Brett achieved what he set out to do, and I don’t see his script as being that far behind what Lifetime puts on the air. What did you guys think?

Script link: Reap What You Sow (new version)

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Brett hooked me up with a couple of writers who have operated in the Made-For-TV-Movie world. After promising each of them a box of Sprinkles cupcakes, they’ve shared with me some trade secrets. They say that Hallmark responds to scripts that promote the wholesome, family love, uplifting thing. While Lifetime is a little more varied. They prefer the tawdry woman in danger scenario. But also like domestic strife, standing up to invaders, and the storybook romance (an old flame rekindled). Any made-for-TV movie fans here? What other secrets can you tell us!?