Search Results for: F word

A friend of mine gave me a script last week with that desperate look in his eyes. You know the look I’m talking about. That tired bloodshot I’ve-been-crying-for-seven-days Shia LaBeouf “I Am Not Famous Anymore” eyes-behind-the-paper-bag look? I looked at my friend and said, “Are you okay?” All he responded with was: “Second act… (then he shook his head) second act.” That was it.

For centuries, screenwriters have stood on the precipice of that second act, looked out at its grand canyon of unknowns, and given up right then and there. I honestly believe that the second act is what sends 80% of the writers who come to Hollywood, looking to break in, back to where they came from. Because when you think about it, the first act is easy. You’re just setting up your concept and your protagonist, something you probably already knew just by coming up with the logline.

But the second act is different. That’s because the second act is where you actually have to BE A WRITER. You have to know how to, you know, craft a story n’ stuff. That takes two things. Practice and Know-how. I can’t do the practice for you. But I can give you the know-how. Now what I’m about to tell you is assuming you already know the basics of structure (and if you don’t, you should buy my book, dammit. It’s only $4.99 right now!). First act is 25% of your screenplay, second act is 50%, third act is 25% (roughly). You should know how to give your protagonist a goal (find the Ark, defeat the terrorists, get your life back on track, a la Blue Jasmine) that is driving him through the story, as well as understand how to apply stakes and urgency to that pursuit. Assuming you’re on top of that, here’s the rest of what you need to know.

Character Development

One of the reasons the first act tends to be easy is because it’s clear what you have to set up. If your movie is about finding the Ark, then you set up who your main character is, what the Ark is, and why he wants to get it. The second act isn’t as clear. I mean sure, you know your hero has to go off in pursuit of his goal, but that can get boring if that’s the ONLY thing he’s doing. Enter character development, which really boils down to one thing: your hero having a flaw and having that flaw get in the way of him achieving his goal. This is actually one of the more fun aspects of writing. Because whatever specific goal you’ve given your protag, you simply give them a flaw that makes achieving that goal really hard. In The Matrix, Neo’s goal is to find out if he’s “The One.” The problem is, he doesn’t believe in himself (his flaw). So there are numerous times throughout the script where that doubt is tested (jumping between buildings, fighting Morpheus, fighting Agent Smith in the subway). Sometimes your character will be victorious against their flaw, more often they’ll fail, but the choices they make and their actions in relation to this flaw are what begin to shape (or “develop”) that character in the reader’s eyes. You can develop your character in other ways (via backstory or everyday choices and actions), but developing them in relation to their flaw is usually the most compelling part for a reader to read.

Relationship Development

This one doesn’t get talked about as much but it’s just as important as character development. In fact, the two often go hand in hand. But it needs its own section because, really, when you get into the second act, it’s about your characters interacting with one another. You can cram all the plot you want into your second act and it won’t work unless we’re invested in your characters, and typically the only way we’re going to be invested in your characters is if there’s something unresolved between them that we want resolved. Take last year’s highest grossing film, The Hunger Games. Katniss has unresolved relationships with both Peeta (are they friends? Are they more?) and Gale (her guy back home – will she ever be able to be with him?). We keep reading/watching through that second act because we want to know what’s going to happen in those relationships. If, by contrast, a relationship has no unknowns, nothing to resolve, why would we care about it? This is why relationship development is so important. Each relationship is like an unresolved mini-story that we want to get to the end of.

Secondary Character Exploration

With your second act being so big, it allows you to spend a little extra time on characters besides your hero. Oftentimes, this is by necessity. A certain character may not even be introduced until the second act, so you have no choice but to explore them there. Take the current film that’s storming the box office right now, Frozen. In it, the love interest, Kristoff, isn’t introduced until Anna has gone off on her journey. Therefore, we need to spend some time getting to know the guy, which includes getting to know what his job is, along with who his friends and family are (the trolls). Much like you’ll explore your primary character’s flaw, you can explore your secondary characters’ flaws as well, just not as extensively, since you don’t want them to overshadow your main character.

Conflict

The second act is nicknamed the “Conflict Act” so this one’s especially important. Essentially, you’re looking to create conflict in as many scenarios as possible. If you’re writing a haunted house script and a character walks into a room, is there a strange noise coming from somewhere in that room that our character must look into? That’s conflict. If you’re writing a war film and your hero wants to go on a mission to save his buddy, but the general tells him he can’t spare any men and won’t help him, that’s conflict. If your hero is trying to win the Hunger Games, are there two-dozen people trying to stop her? That’s conflict. If your hero is trying to get her life back together (Blue Jasmine) does she have to shack up with a sister who she screwed over earlier in life? That’s conflict. Here’s the thing, one of the most boring types of scripts to read are those where everything is REALLY EASY for the protagonist. They just waltz through the second act barely encountering conflict. The second act should be the opposite of that. You should be packing in conflict every chance you get.

Can someone PLEASE write a buddy-cop movie about Shia’s bag and Pharrell’s hat?

Can someone PLEASE write a buddy-cop movie about Shia’s bag and Pharrell’s hat?

Obstacles

Obstacles are a specific form of conflict and one of your best friends in the second act because they’re an easy way to both infuse conflict, as well as change up the story a little. The thing with the second act is that you never want your reader/audience getting too comfortable. If we go along for too long and nothing unexpected happens, we get bored. So you use obstacles to throw off your characters AND your audience. It should also be noted that you can’t create obstacles if your protagonist ISN’T PURSUING A GOAL. How do you place something in the way of your protagonist if they’re not trying to achieve something? You should mix up obstacles. Some should be big, some should be small. The best obstacles throw your protagonists’ plans into disarray and have the audience going, “Oh shit! What are they going to do now???” Star Wars is famous for one of these obstacles. Our heroes’ goal is to get the Death Star plans to Alderaan. But when they get to the planet, it’s been blown up by the Death Star! Talk about an obstacle. NOW WHAT DO THEY DO??

Push-Pull

There should always be some push-pull in your second act. What I mean by that is your characters should be both MAKING THINGS HAPPEN (push) and HAVING THINGS HAPPEN TO THEM (pull). If you only go one way or the other, your story starts to feel predictable. Which is a recipe for boredom. Readers love it when they’re unsure about what’s going to happen, so you use push-pull to keep them off-balance. Take the example I just used above. Han, Luke and Obi-Wan have gotten to Alderaan only to find that the planet’s been blown up. Now at this point in the movie, there’s been a lot of push. Our characters have been actively trying to get these Death Star plans to Alderaan. To have yet another “push” (“Hey, let’s go to this nearby moon I know of and regroup”) would continue the “push” and feel monotnous. So instead, the screenplay pulls, in this case LITERALLY, as the Death Star pulls them in. Now, instead of making their own way (“pushing”), something is happening TO them (“pull”). Another way to look at it is, sometimes your characters should be acting on the story, and sometimes your story should be acting on the characters. Use the push-pull method to keep the reader off-balance.

Escalation Nation

The second act is where you escalate the story. This should be simple if you follow the Scriptshadow method of writing (GSU). Escalation simply means “upping the stakes.” And you should be doing that every 15 pages or so. We should be getting the feeling that your main character is getting into this situation SO DEEP that it’s becoming harder and harder to get out, and that more and more is on the line if he doesn’t figure things out. If you don’t escalate, your entire second act will feel flat. Let me give you an example. In Back to the Future, Marty gets stuck in the past. That’s a good place to put a character. We’re wondering how the hell he’s going to get out of this predicament and back to the present. But if that’s ALL he needs to do for 60 pages, we’re going to get bored. The escalation comes when he finds out that he’s accidentally made his mom fall in love with him instead of his dad. Therefore, it’s not only about getting back to the present, it’s about getting his parents to fall in love again so he’ll exist! That’s escalation. Preferably, you’ll escalate the plot throughout the 2nd act, anywhere from 2-4 times.

Twist n’ Surprise

Finally, you have to use your second act to surprise your reader. 60 pages is a long time for a reader not to be shocked, caught off guard, or surprised. I personally love an unexpected plot point or character reveal. To use Frozen, again, as an example, (spoiler) we find out around the midpoint that Hans (the prince that Anna falls in love with initially) is actually a bad guy. What you must always remember is that screenwriting is a dance of expectation. The reader is constantly believing the script is going to go this way (typically the way all the scripts he reads go). Your job is to keep a barometer on that and take the script another way. Twists and surprises are your primary weapons against expectation, so you’ll definitely want to use them in your second act.

In summary, the second act is hard. But if you have a structural road-map for your story (you know where your characters are going and what they’re going after), then these tools should fill in the rest. Hope they were helpful and good luck implementing them in your latest script. May you be the next giant Hollywood spec sale! :)

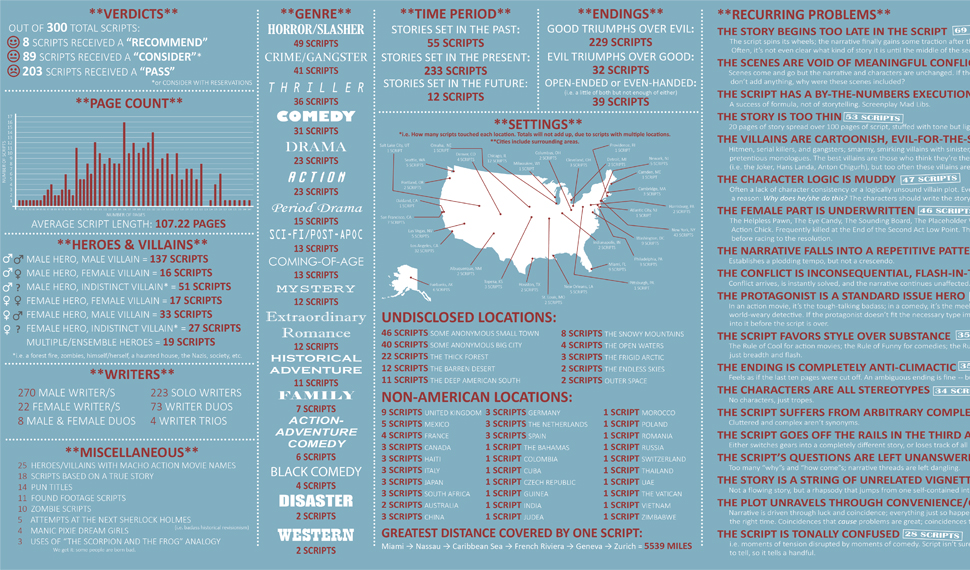

One of the best things to happen to the screenwriting community was this info-graphic. An industry reader read 300 scripts and tracked very specific data on all of them, which allowed him to create a breakdown of all the faults he found. Yeah yeah, that’s kind of depressing. But it’s also helpful! Because guess what? I see these exact same things all the time too and I just say, “Ahhhhhh! Why can’t writers NOT DO these things??” If they understood these pitfalls, screenplays across the world would be so much better. Of course, everybody’s in a different place and we’re all learning at different rates, so yeah, I guess you have to take that into account. But not after today fellas and gals. After today, you are NOT going to be making these mistakes ANY MORE. So, here’s our mystery infographic maker’s TOP 5 mistakes he encountered while reading 300 screenplays, along with my own precious surefire ways to avoid making those mistakes yourselves.

BIGGEST PROBLEM – “The story begins too late in the script.”

(69 scripts out of 300)

Oh my gosh golly loggins, yes, yes AND YES AGAIN. This is SUCH a huge problem in amateur scripts. It’s the radiation poisoning of script killers. What I mean by that is it’s a slow painful way to kill off a script, as the story keeps going, and going, and going, and nothing resembling a story is emerging. This usually happens for a couple of reasons. First, writers can get lost in setting up their characters and world. Sure, setting that stuff up is important, but if you’re not careful, 30 pages have gone by and all you’ve done is set everything up! You haven’t actually introduced a plot. Also, new writers, in particular, use three or four scenes to make a point, whereas pros know to make the point in one. Readers don’t need to be repeatedly told things to get them. Yes, Mr and Mrs. Johnson are having marital problems. But showing four separate fight scenes to get that point across is kinda overkill, don’t ya think?

THE FIX

The first act is the easiest act to structure and, therefore, one you should structure. Somewhere between pages 1 and 15, give us an inciting incident. That means throw something at your main character that shakes his life up and forces him to act. I was just watching the most indie of indie films, “Robot and Frank,” about an old man losing his senses, and his son gets him a robot to take care of him. Guess when the robot shows up? Within the first 12 minutes! So even in an indie movie about old people, the story is STARTING RIGHT AWAY. If they’re doing it, so should you!

SECOND BIGGEST PROBLEM – “The scenes are void of meaningful conflict.”

57 out of 300 scripts

It personally took me a long time to figure this out. “Oh wait,” I realized when I used to spend 72 hour shifts plastered on my laptop screen, “you mean two characters sitting around and talking about life isn’t interesting??” Or a series of scenes with my main character enjoying life could become boring to someone?? It wasn’t until I realized that every single scene needed to have conflict on SOME LEVEL that I truly understood what “drama” meant. Every single scene needs drama, and you can’t have drama without conflict.

THE FIX

Whenever you write a scene, you need to ask yourself, “Where’s the conflict here?” If there isn’t any, add some. I’m going to help you out. Two of the most powerful forms of conflict you can draw on are over-the-table and under-the-table. Over the table is more obvious. Think of two characters confronting each other, a girlfriend who’s just found out her boyfriend has cheated on her. She storms into his apartment and starts yelling at him. They fight it out. Assuming we’re interested in the characters and you’ve set this moment up, it should be a good scene. The far more interesting conflict to use, however, is under-the-table. This is when characters are pushing and pulling at each other, but underneath the surface. For example, let’s say this same girl comes home, but instead of telling her boyfriend what she knows, she acts like everything’s fine. They have dinner, and she slowly starts asking questions. They seem innocent (“What did you do yesterday? Can I use your phone to call a friend?”) when, in actuality, she’s trying to get her boyfriend to admit his guilt, or catch him in his lies. Of the two options, under-the-table conflict is always more fun, but as long as there’s SOME conflict in the scene, you’re good (note, there are other forms of conflict you can use. These are just two options!).

THIRD BIGGEST PROBLEM – “The script has a by-the-numbers execution.”

53 out of 300 scripts

Has someone been spending too much time trying to fit their story into Blake Snyder’s beat sheet? Have you become so obsessed with The Hero’s Journey that you’re starting to pattern your breakfast after it? We were just talking about this yesterday with The Lego Movie script. If you follow formula too closely, it becomes extremely hard for your script to stand out. When I see this, it’s almost always coupled with a boring writing style. The combination leaves the script with no unique identifying value. It is the “anti-voice” script, the equivalent of one of those knock-off Katy Perry songs. The writers most susceptible to this actually are NOT new writers, but writers on their 4th or 5th script. That’s because new writers don’t know about rules yet. It’s the writers who are starting to put in the work and learn how to tell a good story, who then follow the advice a little too literally.

THE FIX

You have to break a few rules. Your script will never stick out unless you take some chances. And actually, the rules you break define your script. For example, using an unlikable protagonist. It goes against conventional wisdom, but if you have a good reason for it and it works for the story, then take the chance. The most susceptible writers to this kind of mistake are SCARED writers. Writers who fear taking chances. They want to play with their story in their safe little bubble. I say surprise yourself every once in awhile. Try something with a plot point you never would’ve normally done. See where it takes you. If you’re surprised, there’s a good chance the audience will be too. And if this is a serial problem for you (everyone’s always telling you your scripts is very “by-the-numbers”), I suggest writing an entire script that’s completely weird and totally different from anything you’ve done before. Tell a story like 500 Days of Summer, where you’re jumping around in time, or Drive, where you’re crafting the story with actions as opposed to dialogue. You’re not going to grow unless you take chances.

FOURTH BIGGEST PROBLEM (tie) – “The story is too thin.”

53 out of 300 scripts

This is usually a problem that begins at the concept stage. Someone picks an idea that doesn’t have enough meat in it. Sofia Coppola’s “Somewhere” is a good example of this. “A guy spends time with his daughter.” When there’s not enough meat, there isn’t enough for your characters to do, and so long stretches of the script go by where nothing happens. Since you’re not a writer-director like Sofia and therefore don’t have funding to make these movies, your scripts can’t afford this pitfall. What it really comes down to is an absence of plot points, the major pillars in your scripts that slightly change the story or the circumstances surrounding your characters, sending it in a different direction.

THE FIX

First, make sure your concept packs a lot of story opportunities. A script like Inception – where teams of people are travelling inside minds – there’s ample opportunity to cram a ton of story into those 120 pages. Also, keep your plot points close together. Something that changes the story slightly or keeps it charging forward should be happening every 10 to 15 pages. So let’s say you’re writing a script about a guy who wins the lottery. On page 20, his ex-girlfriend who dumped him may show up at his door. On page 32, he finds out he’s being sued by someone who says he stole the lottery ticket from him. On page 46, he gets robbed coming out of the bar. Make sure things keep happening consistently during the script to avoid the “thin” tag.

FIFTH BIGGEST PROBLEM – “The villains are cartoonish, evil for-the-sake-of-evil.”

51 out of 300 scripts

This is almost exclusively a beginner mistake. Beginners remember their favorite villains as being over-the-top and quirky in one particular area (an accent, an eye-patch) and think, “Perfect! That’s all I need to do for my villains too!” So they only focus on how the villain acts on the OUTSIDE as opposed to what’s going on on the inside.

THE FIX

With villains, you have to start on the inside. I KNOW people hate doing all this work, but I’d strongly suggest busting out a new Word Doc and writing down as much as possible about your villain. Find out where he grew up, what his childhood was like (was he bullied? Abused? Ignored? Alone? A victim of affluenza?) Any of these could explain why he became the way he did. The more you know about your villain, the less cliché he’s going to be. And remember, the villain always believes he’s the hero. He truly believes in his cause. One of the easiest ways to lead your villain to the cliché troth is to assume he knows he’s bad and loves it. Villains are much more horrifying when, like Hitler, they actually believe what they’re doing is right.

note: Whiplash review coming tomorrow.

Genre: Thriller

Premise: A Los Angeles drifter with big dreams finds himself drawn into the world of “nightcrawling,” a practice where independent videographers search out violent crimes and sell them to news shows.

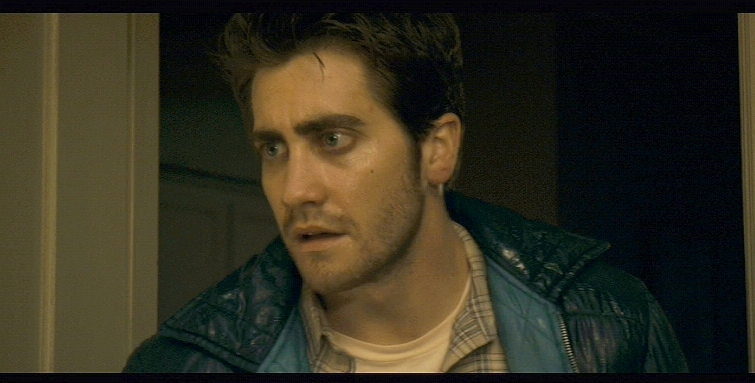

About: Recently Jake Gyllenhaal left the giant Disney musical, Into The Woods, because funding for this film finally became available and he loved the script so much, he didn’t want to pass it up. I figure if someone’s passing up big studio money to do a small indie film, the script must be pretty great. Dan Gilroy is best known for writing The Bourne Legacy, The Fall, and Two For The Money.

Writer: Dan Gilroy

Details: 108 pages – 11/27/12 draft

Jake Gyllenhaal has been trying to break through into that A-list category for awhile now. But no matter what he does, he’s still stuck in that B – B+ category. Actors who can bring you 10-15 million on opening weekend, but not much more unless they’re paired up with a big actor. So how do you get onto that A-list? It’s simple. Find a great character. If you can find a great character and you nail the performance, the film stays in the theater longer, which leads to more accolades, which leads to more publicity, which leads to possible Oscar nominations. And all of a sudden, when that big new production needs a star, the first name on producers’ lips is… Jake Gyllenhaal!

Which is exactly why you want to write interesting unique characters. Every actor out there is dying to find that character that’s going to light up their career. Today’s script is a perfect example. Gyllenhaal actually left a film where they drape you in money just because of the Nightcrawler lead. That’s how rare these opportunities are and why actors jump when they get their chance because writers just don’t write enough juicy characters. And make no mistake, the role in Nightcrawler is about as juicy as they get.

20-something Louis “Lou” Bloom is like a lot of people in Los Angeles. He’s trying to become relevant. He’s trying to get a job. He’s trying to make money. He’s trying to find a place that doesn’t look like a janitor’s closet. The man is desperate to find a life of importance.

Lou is also… strange. You aren’t going to find an easy way to describe him but if pressed I’d say he’s an ambitious sleazy sociopathic hustler with a tinge of autism. He will steal your bike the second you turn away, then sell it to the bike store on the next corner with a load of bullshit so tall it’d dwarf the tallest hill in Hollywood.

Here’s a little taste of that action, where he’s trying to run up the price on the bike store owner who sees right through him: “This is a custom racing bicycle, ma’am, designed for competitive road cycling. This bike has a lightweight, space-age carbon frame and handlebars positioned to put the rider in a more aerodynamic posture. It also has micro-shifters and 37 gears and weighs under six pounds. I won the Tour de Mexico on this bike.” Bike Store Owner: “No bike has 37 gears.”

So one day, Lou happens upon a nasty car wreck where a young woman is stuck inside a burning vehicle. He notices a couple of independent videographers taping the ordeal. Armed with every cop radio frequency in town, it’s clear these guys race around to wherever bad shit is happening, tape it, then sell the footage to the news stations.

Fascinated, Lou buys himself his own video camera and starts doing the same. The big difference between Lou and his much more experienced competition is that Lou is, well, FUCKING CRAZY. He will drive 95 on side streets to make sure he gets to wherever the hell the action is first. This means he always gets the best footage, and he starts selling it to the news shows for big money, or one station in particular – K.S.M.L.

K.S.M.L. is in the gutter and therefore desperate. That means they’re willing to show crazier violence and pay more. Lou takes a particular interest in the director of K.S.M.L.’s news, Nina Romina. She’s twice his age but that’s just fine. Lou has a thing for older women. When she doesn’t show interest in him, Lou just uses his leverage: “You don’t want me [sexually], I don’t wanna give you the footage I found.” Nina knows Lou is her meal ticket and therefore, obliges Lou’s advances.

Eventually, however, the oven starts burning too hot. Sweeps is coming up and while Lou is still the best in the business, Romina needs something huge. It’s at this point that Lou realizes, if he’s going to find a story truly mind-blowing story, he can’t wait for the news to happen. He’s going to have to create it himself.

Man oh man oh man is Gilroy a good writer. This script just flew by. He’s one of the few writers who can be descriptive with barely any description at all.

LOS ANGELES

Shimmering in night heat… THRUM of civilization… a FREEWAY feeds into the city as a SEMI blasts by and CUT TO

A COYOTE

Loping across a RESIDENTIAL STREET in the hills… it stops under a street lamp… darting away and CUT TO

THE L.A. RIVER

For those of you who’ve read my book, you know one of the movies I broke down was Taxi Driver. But I almost didn’t include it. I thought to myself, people don’t write like this anymore. You can’t write Taxi Driver in this day and age, so what’s the point of using it as an example? I now realize I was wrong. You can write a movie like this. You just have to update it to a new time, to a new collective sensibility. You can still have a dark fucked up character running around a city doing dark questionable things, but it needs to be faster. It needs to have more pop. More energy! Enter “Nightcrawler.”

And, of course, if you’re going to write the next Taxi Driver, you gotta have your modern day Travis Bickle. Dan Gilroy found that character in Lou. This guy is just… I can’t even summarize him really. He’s that complex. There’s this moment that encapsulates him best where he basically blackmails Nina into giving him more of the action. However, there’s a detachedness to the way that he speaks, as if he both wants and doesn’t want what he’s asking for:

“Now I like you, Nina, I look forward to our time together, but you have to understand that 25,000 isn’t all that I want. From here on, starting now, I want my work to be credited by the anchors and on a burn. The name of my company is Video News Productions, a professional news gathering service. That’s how it should read and that’s how it should be said. I also want to go to the next rung and meet your team and the anchors and the director and the station manager, to begin developing my own personal relationships. I’d like to start meeting them this morning. You’ll take me around and you’ll introduce me as the owner and president of Video News and remind them of some of my many other stories. I’m not done. I also want to stop our discussions over prices. This will save time. So when I say a particular number is my lowest price, that is my lowest price and you can be sure I’ve arrived at whatever that number is very carefully. Now when I say I want these things I mean that I want them and I don’t want to have to ask again. And the last thing that I want, Nina, is for you to do the things I ask you to do when we’re alone together at your apartment, not like the last time.”

I mean, how are you NOT going to want to play that character if you’re an actor?

On top of the character stuff, this script is a great discussion companion for a previous article, The Six Types of Scripts Least Likely To Get You Noticed. One of those scripts I was trying to warn you away from was the coming-of-age story. However, I said if you refuse to listen and still want to write one, try to add a fresh angle to it. Don’t write the traditional coming-of-age story. Write something different.

Nightcrawler is exactly that. This is about a confused man who ends up finding his calling (coming-of-age). But he does it amongst a rocket-fast storyline and a unique subject matter we haven’t seen on screen before. Gilroy took a coming-of-age story and turned it into a thriller. If you are going to take chances and write stuff producers typically hate, the least you can do is that.

Gilroy did it and wrote a classic script in the process.

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[x] impressive (TOP 25!)

[ ] genius

What I learned: Characters whose demeanor opposes their desire can be quite fascinating. Lou is desperate to move up, yet seems completely disinterested whenever discussing so. He’ll blackmail you, but do so without the slightest hint of emotion. In other words, if you have have a character ordering a hit, have him laughing while he does it. If you have a character who’s steaming mad, have him deliver his side of the argument with a smile. That contrast never quite fits when we’re watching it happen and is therefore always engaging to watch.

My new best friend Sean and I are hanging out later. So I just wanted to post a picture of him.

My new best friend Sean and I are hanging out later. So I just wanted to post a picture of him.

One of the most frustrating things about going through all these scenes was reading scenes that just didn’t go anywhere. Nothing was happening. And here’s where you see a major difference between experienced screenwriters and new screenwriters. It’s the difference in their interpretation of the phrase “something happens.” In a script, in every single scene, in order to keep a reader riveted, something NEEDS TO HAPPEN. Beginner writers say, “Hey, that conversation between me and my co-worker about our douchey boss was kind of funny. I’ll put that in a script.” And they do. And they don’t understand why no one responds to it. It was cute. There were a few funny lines. And it was life, man! Real-world shit! The reason nobody cared is because nothing happened.

Experienced writers know that “something happens” means ratcheting up the stakes and bringing something big to the table, a scene where what people say actually matters, where there are consequences to people’s actions! If they’re going to write a scene about two co-workers, one of them is going to have a gun hidden in her jacket. She and her co-worker had an affair. He’s broken it off. She’s been e-mailing and texting and calling him to no avail. He barely responds to her. Echoes of Fatal Attraction. She’s finally convinced him to have lunch with her. She’s brought a gun to their little chit-chat and is considering using it if the conversation doesn’t go well. Now, something is happening.

There’s an old saying with writing screenplays. It goes something like this: Your story should be about the most important thing that’s ever happened to your character in his life. In other words, if what you’re writing about isn’t even the biggest thing that’s happened to your hero, why do you think we would be entertained by it? I think you can apply this approach, at least partially, to scene-writing. The scenes you write should be the biggest 1, 2, or 3 things that happened to your character that day. There will be exceptions to this for sure. But if you’re picking your best scene in the whole script? One that really shows off your chops? And it doesn’t even seem (or barely seems) like it was the most important thing that happened to your character that day? How do you expect a reader to be impressed?

But here’s the real killer. The writers who WERE able to write a scene where something was “happening?” The ones who avoided that pothole? They often made the mistake of writing the scene in the most predictable way possible. Those are some of the hardest scenes to read. Because here we are. This huge scene is laid out before us (i.e. Hero finally confronts his mother who left him as a child), and it… goes… exactly… according… to plan. He asks mom why she did it. She takes a deep breath. Says she doesn’t know. She thinks about it. Talks about how it was all too much for her. I mean, WE’VE SEEN THAT SCENE BEFORE! We’ve seen it a billion times.

I just don’t understand why screenwriters don’t realize this. Why they don’t realize that we’ve been down that road before. As a writer, it’s your job to know the reader’s expectations, and then go in a different direction. That way you surprise them as opposed to bore them. This to me, is what all the best writers do. And it’s one of the easiest skills to learn. You don’t have to be a master storyteller to do it. All you have to do is recognize the way a scene typically plays out, and go another direction. Even if that direction turns out to be a bad choice, at least we’ll applaud you for not taking the obvious route.

Another thing that shocked me is I don’t think I read a single “Hitchcock bomb under the table” scene out of all the submissions. Someone can correct me if I’m wrong (Miss SS read a few submissions so maybe she did) but I didn’t see one. This is one of the EASIEST ways to write a good scene. You should have 2-3 versions of this scene in every script you write. Maybe more depending on the genre. Essentially the idea is, if you have two people talking at a table, it’s boring. But if you tell the audience there’s a bomb underneath the table, a ticking bomb, then all of a sudden the scene becomes interesting.

This is where Sean and I met. Memories.

This is where Sean and I met. Memories.

You can apply this to a scene in a million different ways. I just did above. The two co-workers talking, one of them secretly has a gun they’re planning on using. That’s a Hitchcock scenario. The scene with John McClane and Hans on the roof in Die Hard. We know he’s the bad guy. John doesn’t. That’s a Hitchcock scenario. A 17 year old girl is going out with a 35 year old biker that nobody in her family likes. There’s a big family dinner. The girl and the guy are planning on dropping the bomb that they’re getting married. That’s a Hitchcock scenario. If you want to win a scene contest, write a good “Hitchcock scenario” scene and, at the very least, you’ll be in the running.

Not every scene has to be a world-beater. Comedy is different. As long as you’re funny, you can get away with not much “happening.” But you have to be a freaking dialogue master to pull that off. You have to write dialogue that SINGS. When you give your script out to people, you better always be receiving the compliments “Your dialogue was great” and “I couldn’t stop laughing.” If not, do not try to rest on your dialogue alone. But to be honest? Why not do both? Why not create those intense pressure cooker situations that make scenes pop ALONG with the comedy? That’s why Meet The Parents was so good. They did such a great job setting up the stakes of that dinner scene. With how much Ben Stiller’s character wanted to impress Robert DeNiro’s character (his girlfriend’s father). They made it clear that everything was riding on his performance at that dinner table. So each word spoken was a potential death trap. Then, when they’re bantering back and forth about whether cats have nipples, it’s not just the writer trying to show you how funny he is. It’s Ben Stiller’s character digging a hole the size of the Grand Canyon trying to find a way out of his continued screw-ups. When we’re emotionally invested in a scenario, we’ll always laugh more.

Despite my passionate plea for better material, this week was really cool for me because I usually read everything within the context of the script. This placed my focus SOLELY on the scene. The scene had to live or die on its own. And it made me realize that each scene, in its own way, is like a script. It’s got its setup, its conflict, and its resolution. It needs goals, stakes, and urgency. It needs conflict. But most of all, it needs to matter. We need something important to be happening or else we’re going to tune out. And you guys need to treat it like that. Treat every scene with pride, like it’s its own story, and try to write the best story you possibly can. If you do that, the next time I hold one of these contests, you won’t have to choose a scene from your script. Because every one of them will be great.

Genre: Rom-Com

Premise: (from me – based on limited information) A young man finds his relationship threatened when the former love of his life, now a famous singer, makes an unexpected visit.

About: A couple of interesting points to make. One, this is Illi’s first screenplay. And two, it was a finalist in two New York screenwriting contests (the New York Screenplay Contest and the Screenplay Festival).

The setup: John has been dating a girl, Lucia, who has no idea that he used to date the famous singer, Verena, who’s currently in town. John actually bought the ring to propose to Verena a long time ago but never did. Lucia finds the ring and believes John is proposing to her. John tells her the truth in an inadvertently asshole-ish way, and she dumps him. So John goes to the supermarket where she works to apologize and get her back with a big surprise.

Writer: Illi Ferreira

Details: 7 pages

As I went through scene submissions, one of the most interesting things I found was which scenes people picked to send. I quickly realized that WHAT a person sent was a quick indication of where they were as a screenwriter. Some scenes were literally two pages long, bridge scenes, that had our characters moving from one place to another, discussing immediate plot points, probably the most un-dramatic moments in the entire script.

Others thought huge action scenes were the way to go. I know that’s what I reviewed yesterday, but that’s because the scene was constructed soundly and well-written. Typically, big action scenes aren’t what a script is about. A script is about the characters and what’s going on between them, whether those problems be familial, relationship-based, or work based. A good scene to pick, I think, would be something revolving around one of those relationships, that showed a clever set up, intriguing conflict, a surprise or two, wrapped in a slightly unexpected package. That’s what I was looking for. Scenes that made you think a little.

Instead I got a lot of obvious straight-forward scenes where characters were saying exactly what was on their minds (no subtext). A lot of shooting. A lot of yelling. A lot of plot-reciting. At least with today’s scene, the writer put some thought into his characters and came about their interaction in a slightly different way.

For those too tired to download the scene, it has John, our main character, show up at Lucia’s work (she’s a cashier at a grocery store) to apologize for being mean the other day. Of course, because she’s working, he has to buy something – each item a sort of “time credit” for him to continue his apology. She’s not hearing any of it though, and is trying to speed him through the line. Customers appear behind him, putting pressure on him to hurry up. Can he get her to accept his apology in time? Or will he fail and lose Lucia forever?

You remember the term “scene agitator” from my book, right? This is when you add an element to the scene that agitates your characters, that makes it more difficult for them to do… whatever it is they’re doing. Here, we see that agitator in the form of a checkout line. John cannot speak freely with Lucia because she’s at work. In order to talk to her, he must buy something like everyone else. Then, when he gets in line, he only has until the end of the sale before he has to leave.

I thought this scene would be fun to discuss because it presents the writer with a choice. That’s the thing with writing. It’s never one simple route. Often, you’re going to have tough choices, with each choice having its own pros and its cons.

So here, John gets in line and starts pleading his case to Lucia. The idea is to make things tough on John, right? We want time to be running out for his apology. So traditionally, you’d put someone behind John – preferably someone very impatient. And that’s what Illi does here. He puts an old woman behind him.

But Illi decides to go another route and pull some laughs out of the situation. In order for John to continue to talk to Lucia, he needs to keep buying things. So he keeps grabbing a new bag of chips off the rack every five seconds or so. After awhile, seeing what he’s trying to do, the woman behind him starts grabbing chips for him. She starts helping him, which is kind of funny.

In other words, there was a choice. We could go with the option that provided the most drama for the scene. Or we could add some humor. Illi opted for humor. Which is fine. But the scene did lose a little bit of that urgency as a result. If we would’ve seen an impatient businessman behind John, and every 30 seconds another impatient shopper got into line, now we’re REALLY going to feel some dramatic tension.

When you’re writing any sort of character interaction, I think you’re trying to put your characters in less-than-ideal situations to have that conversation.

Have you ever set up a plan to tell someone you liked them? And you have it all worked out perfectly how you’re going to do it? You’re going to go to their work, wait for them outside, greet them with a surprised ‘hello,’ offer up a few carefully practiced jokes, then casually ask them out to a movie? But it never goes like that does it? You wait for them outside their work. They end up being late. So it gets dark. Now you look like a stalker. A night time guard approaches you, suspicious. He asks you what you’re doing out here. You nervously tell him you’re just waiting for a friend. He doesn’t believe you, so he stands nearby and watches you. The girl finally comes out. You’re freaked out about the guard so you look nervous and jittery. She picks up on that and now she’s creeped out. Right before you get to your first joke, some guy comes out, puts his arm around the girl. “Hey, you ready?” he asks. She looks at you. “Yeah, just a second. (to you) What were you about to ask me, Joe? Something about a movie?”

Whenever you want to talk to anyone about something important, it NEVER goes how you plan for it too. And that’s really how good dialogue scenes work. Whatever was planned goes out the window because all these unexpected things should be popping up. Sure, the perfect “nothing goes wrong” scenario is wonderful for real life. But it’s boring as hell for the movies.

I liked how Illi created that imperfect scenario, which is why I liked his scene. That doesn’t mean there weren’t problems. I couldn’t put my finger on it but the scene itself felt a little clunky. There were too many action lines between the dialogue, making it difficult to just read and enjoy the scene. I thought the dialogue was okay, but not exceptional. And in rom-com spec sales, the dialogue is always really strong. So Illi still has a ways to go. But this was a solid effort for sure.

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Dialogue scenes benefit immensely from a time limit. Create some reason why your characters have to get their conversation over quickly, and you’ll find that your scene instantly feels snappier, more energetic.