Search Results for: F word

Genre: Dark fantasy

Premise: In the city of The Burgue, a police inspector pursues a serial killer who is targeting fairies.

About: Travis Beacham sold this script back in 2005. While becoming a town favorite, it has often been deemed too expensive to make, particularly because it doesn’t have a pre-built in audience. However, the script jump-started Beacham’s career and allowed him to do assignment work on some of the biggest projects in town. He eventually got sole credit on Clash Of The Titans, and is the writer on Guillermo del Toro’s upcoming self-proclaimed “biggest monster movie ever,” Pacific Rim. If you’re a writer who wants to write big Hollywood effects-driven flicks, Travis Beacham is probably your template-writer on how to get there.

Writer: Travis Beacham

Details: 116 pages – July 22, 2005 draft (This is an early draft of the script. The situations, characters, and plot may change significantly by the time the film is released. This is not a definitive statement about the project, but rather an analysis of this unique draft as it pertains to the craft of screenwriting).

Do not adjust your screens. That déjà vu you’re experiencing does not mean the Matrix has reloaded. Killing on Carnival Row HAS been reviewed on Scriptshadow before. But it was Roger who reviewed it, not moi.

Before and since then, I have heard numerous screenwriters tout how this screenplay is the greatest thing since Final Draft. Imaginative, daring, edgy, fascinating, original, dark – these adjectives bombard my sensitive ears whenever Killing on Carnival Row’s brought up. Which begs the question? Why haven’t I read it?

Well, I don’t dig the fairy thing. These kinds of fantasy worlds remind me of Harry Potter, whose movies have provided me with some of the more severe “what the fuck” expressions that have ever graced my mug. So the last thing I wanted was to crash the party with a big fat negative review of a script everybody considered their script girlfriend. So I avoided it. And avoided it. And avoided it. And then one day I woke up and for no good reason proclaimed, much like Annette Benning’s character in American Beauty, “I shall read Killing On Carnival Row today!” But I knew if I was going to do this, I was going to have to do it in style. So I went to the costume shop and bought one of those cheap fairy costumes. I strapped on my wings and got ready to immerse myself in The Burgue.

Worgue.

Killing on Carnival Row introduces us to Inspector Rycroft Philostrate. Besides being a mouthful, Philostrate is kind of this deep dark dude who roams this deep dark city known as The Burgue. Philostrate has just learned of the killing of a poor defenseless fairy, and it’s his job to find out who the killer is.

The main witness at the crime scene – to give you an idea of how weird this world is – is a seal/sea creature named Moira who speaks in song. She sings out what she saw, probably making things more confusing than they were in the first place. But that’s okay, because we later find out that she impressed enough people to make it to Hollywood Week on The Burgue Idol.

Philostrate surmises from the Rebecca Black breakdown that the place to look for answers is Carnival Row, the quarter of The Burgue where all fairies live. But we soon find out this isn’t a professional visit. Oh no. It turns out Philostrate is in love with a fairy hooker named Tourmaline. So the two make some very graphic but very sweet human-fairy love, and afterwards throw out wishful asides about becoming a “real couple” someday. Riiiiight. Not to ruin the moment here guys, but there’s a bigger chance of Harry Potter hooking up with Volgemart.

Anyway, our fairy killer isn’t done fairy killing yet, and after taking out another clueless wing-flapper, he kills Tourmaline herself, the hooker fairy! Uh-oh, shit just got personal. And to make things worse, the press has picked up on the ordeal. They’re calling our fairy serial killer: Unseelie Jack (I think “Seelie” is the name of one of the quarters in The Burgue. But I can’t tell you for sure. This is a script where, remember, people peel off seal-like exteriors and speak in song).

Philostrate is pretty down about the whole Tourmaline thing, but apparently not that down, cause he starts hooking up with this other fairy named Vignette quickly afterwards. Karma comes back to bite his ass though, as Philostrate soon becomes the number one suspect for the fairy killings! Say what!? That’s right. They think HE’S Unseelie Jack. So Philostrate does his best Harrison Ford impression, trying to solve the case while on the run, and develops deeper and deeper feelings for Vignette. Will they catch him? Is Philostrate Unseelie Jack? Find out…well…in the comments section here on this review.

I’m guessing you already know where I stand on this one. In a lot of ways, Killing on Carnival Row was exactly what I expected it to be. A story where film geeks go to gorge themselves. You got your dark noir-ish city. You got your hot naked fairies. You got your half-human half-seal singing whatchumacalits. This is a movie that David Fincher or Guillermo del Toro would hit out of the park. In fact, this script is basically Seven meets the fairy world. Meets Harry Potter. I’m not sure what fairy sex would look like onscreen, but this movie wants you to know.

The writing style’s also very visceral. I may not have liked the world I was in, but I definitely felt like I was there. There is no doubt Beacham thought this universe up and down and back and forth. Carnival Row has the same attention to detail as films like Star Wars, Avatar, and even Lord Of The Rings. Reading it is kind of like the difference between playing a good video game and a bad video game. In a bad video game, you walk outside the expected field of play and you see a bunch of blurry pixels. Do the same thing in a good video game, and you might find this huge beautiful wheat field, glimmering in the sunset. The details and depth here are just first rate.

In fact, I think Beacham’s kind of a genius in that sense. When you think about the highest paying screenwriting jobs in Hollywood? They’re usually effects driven films with lots of monsters. So why not show Hollywood you can write effects driven movies with lots of monsters? But the difference between Beacham and everyone else who takes this approach is that Beacham really studied his world. This isn’t some slapped together paper-thin universe. This is a full blown bona fide mythology. Carnival Row may not ever be made, but the script will be reaping assignment residuals for the rest of Beacham’s life.

Another biggie I realized halfway through the script, is that even though I wasn’t into the subject matter, I would definitely go see this movie. I mean, imagine the trailer for this sucker. Naked fairies and huge mechanical dragonfly blimps and singing seal whatchumacalits. It would be unlike anything you’ve seen before. And I think that’s what I’m forgetting here. My narrow-minded grown-up Harry Potter references aside, you have never seen a movie like this in your life. That alone should merit making it.

As for the script itself, let’s just say while reading it, I felt like the uptight yuppie dude walking through downtown Tijuana. I had a hard time comprehending what the hell was going on half the time. For example, fairies are often referred to as scum in this world. But I always thought fairies were cute and sweet. Tinker Bell may be many things – annoying near the top of the list – but I’d never equate her to a cockroach. Why they gotta be so fairy racist in this movie? I couldn’t wrap my brain around it. Trolls. Yuck. Lizard people. Icky. Fairies? Cute!

And on the story front, I had a hard time figuring out why the hell they were after Philostrate. One second Philostrate’s the main detective on the case. Next, he’s the main suspect. Hold up, WHAT?? When the hell did this happen?? Did I miss something? Don’t you have to, like, have the one-armed man kill your wife but she erroneously whispers your name into the phone before she dies to become a number one suspect in a murder? If someone could explain this plot point to me, I would be grateful.

But when it was all over? I appreciated Carnival Row. It’s different. It’s bold. It’s extremely well-written. So I definitely think it’s worth reading. But I will not be joining Team Philostrate or Team Tourmaline any time soon.

linkage: While I won’t be linking to the script here, this script can actually be found online. Just type the title and “PDF” into google and you should find it no problem.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Pay particular attention to the way you describe your action. If you look at the first scene in Killing on Carnival Row, you’ll find a lot of descriptive visceral words. “Laboured BREATHING” “SPLISH SPLASH” “BURSTS” “Eerie WAIL” “slams” “kicks free.” Notice how I haven’t even told you what the scene was about but you still have a strong sense of what’s happening. Compare that to if I used, “runs” “flies” “screams” “breathes”. Those words do the job, but not nearly as effectively. So choose your adjectives and your descriptive phrases wisely. You want to connect with that reader on a visceral level.

Genre: Sci-Fi Comedy

Premise: Set in the future, a married couple trying to join an exclusive orbiting community (above earth), is forced to adopt a 13 year old girl due to the community’s “families only” policy. Little do the girl and the community know, the couple’s intentions aren’t so kosher.

About: Every Friday, I review a script from the readers of the site. If you’re interested in submitting your script for an Amateur Review, send it in PDF form, along with your title, genre, logline, and why I should read your script to Carsonreeves3@gmail.com. Keep in mind your script will be posted in the review (feel free to keep your identity and script title private by providing an alias and fake title).

Writer: John Sweden

Details: 97 pages (This is an early draft of the script. The situations, characters, and plot may change significantly by the time the film is released. This is not a definitive statement about the project, but rather an analysis of this unique draft as it pertains to the craft of screenwriting).

I’ve been hearing some strongly opinionated rumblings about this script all week. I just want everyone to remember, this isn’t Trajent Future we’re talking about here. We don’t have the writer telling everyone they’re idiots for not liking his script (or at least, not yet). My assessment of John Sweden is that he’s a nice guy, someone interested in the craft, but whose proximity to screenwriting may not be as close as the rest of us. We all started somewhere. We all know what those early scripts of ours looked like, so don’t be mean here. Be critical, but don’t be mean. Now, having said that, I have to call it like I see it, so to Mr. Sweden, take a seat. There’s going to be some tough love in this breakdown. Try to take it constructively. In the end, it’s about learning from your mistakes and becoming a better screenwriter the next time around. :)

The first hint that something’s off here comes in that DAD and MOM, the main characters in Orbitals are referred to in quotes throughout the screenplay. So they’re “DAD” and “MOM.” Anyway, “Dad” and “Mom” are obsessed with sex. In fact, the movie starts out with them trying to make a sex tape. I’m not sure what this has to do with the story, other than maybe being a viral offshoot of Monday’s script review, but it’s a pretty darn strange way to open a script, I’ll tell you that.

Anyway, the other thing “Dad” and “Mom” do is swear a lot. Fuck this and fuck that and fuck fuck fuck and lots of use of the word fuck. I did a word count and there are over 150 uses of the word fuck. That’s almost 2 per page!

Now I’m a little confused about this next part, but I think “Dad” and “Mom” work for the military. And they need to get up to this orbiting community to execute a top secret plan. Unfortunately, the “Orbitals” don’t allow you up there unless you’re a full family, with children and such. So “Dad” and “Mom” decide to adopt a teenager.

Luckily for us, “Teenager” has a real name. Aubrey. And Aubrey, just like her new parents, likes to use the word “fuck” a lot. Now for reasons that aren’t entirely clear to me, once they have Aubrey, they do not go on their mission. They instead hang out at their apartment, celebrate a birthday, go shopping, try to have sex a few times, and watch movies. After awhile, they decide it’s time to head up to Orbital-Land, where we quickly learn their intentions aren’t as pure as we thought. “Dad” and “Mom” are terrorists! And they’re planning on blowing up the entire Orbital community – while discussing sex of course.

I’m just going to tell you right now – Orbitals is getting the worst Scriptshadow rating there is. And I don’t want to discourage John because this is not a rating that reflects his writing for the rest of his life. It is a rating that reflects this script only. The great thing about screenwriting is that as long as you have the drive, you can keep learning, keep getting better. This is probably a rating that would reflect every screenwriter’s first screenplay – which I assume that this is – so try to take these notes as constructively as possible.

When I first got to LA, I wrote a script with a friend and we managed to finagle it into a few pretty big hands by basically lying our asses off. We told our few contacts that we’d written something that huge producers were interested in (lie), tricking them into reading it themselves.

Eventually, a really big agent agreed to “have lunch” with us and we prepared for our imminent big break. “I knew this was going to be easy,” I thought, mapping out which kind of car I was going to buy, a Bentley or a Ferrari. Now let me tell you something I learned in retrospect. This script was fucking AWFUL. Like the worst script you can imagine. It was about the internet coming alive or something. I don’t even remember exactly because I’ve tried to purge my brain of its existence. To give you an idea of how bad it was, we gave the script to a couple of 15 year olds since that was our target demo and one of them came back and said it was the single worst thing he had ever read in his life. He actually thought we were kidding. “You didn’t really write this, did you?” He was 15! 15 year olds like everything!

Anyway, we later realized (hindsight is a beautiful thing huh?) that the agent who was most certainly going to give us our big break, wanted nothing to do with us. She was doing a favor for the person who gave her the script, who she thought was a lot closer to us than she actually was. So she sent her crony assistant, this total Hollywood douchebag who spent more effort trying to pick up our waitress than talk to us, which in retrospect sucked because we convinced ourselves the guy was a moron and therefore ignored everything he said to us. But the guy gave us some really important advice that I only grasped 5-6 years later. This is what he said.

Writing screenplays is not a joke. You are competing against guys who have dedicated their lives to this craft, who have a 15-20 year head start on you. These are the Derek Jeters and the David Beckhams of the screenwriting world. They will spend 1-2 years on their screenplay. They will have written 30-40 drafts. They will go over every scene 200-300 times. They will make sure every line of dialogue is sharp, relevant, reveals character, and pushes the story forward. They will obsess over that screenplay like you wouldn’t believe. And because they’ve written 30 screenplays already, they will know where all the mistakes are and how to fix them.

If you think you can just slap together a high concept idea with 2 good scenes and a threadbare story that barely makes sense and compete with that? You’re off your fucking rocker.

The agent-assistant (whatever he was) then made us pick up the tab and went over and asked that waitress out (she said yes) and in that moment I hated everything about Hollywood. But you know what? He was right. He was so very right. This isn’t a joke. It doesn’t matter how many bad movies you’ve seen. If you expect to break in with a script you wrote in 14 days? If you think that professionals in this business won’t be able to tell that you wrote the script in 14 days, due to its unoriginality, its sloppiness, its 70% of scenes that repeat information we already know, its lack of character development? That readers won’t know that you didn’t think a single plot point through or do more than a single rewrite, you’re crazy. The guys who matter know these things. You cannot trick them.

That’s not to say newcomers can’t write something decent. But if you want a fighting chance, go out and read the 5 best-selling screenwriting books so you have SOME idea of how to tell a story. Read at least a hundred screenplays so you know what kind of quality you’re going up against. Plot out your story beforehand so it doesn’t look like something that was made up on the spot. When you’re finished, read through it and note all the places you were bored. Come up with solutions and then rewrite it. And when you’re finished, repeat that process. Again. And again. And again. Give it to friends and ask them what parts they liked and didn’t like. Incorporate those responses. Rewrite it again. And again. And again.

Honestly, I don’t know where to begin with Orbitals. I guess I’ll start with the basics. Movies are about only giving the audience the good parts and cutting out all of the boring stuff. Orbitals is written the opposite way. It only gives you the boring parts, and could care less about the interesting stuff.

For example, the script is supposedly about a couple who adopts a girl to get access to the orbiting system above earth that they normally wouldn’t have access to. Therefore, when they adopt the girl, you’d think that we’d be – you know – on our way to the orbiting system. No. Orbitals spends the next 50 pages back at the apartment with its two lead characters talking about sex. That is not the “good parts.” The equivalent would be like in Star Wars, after Obi-Wan and Luke went and got Han as their pilot to go to Alderran, they then went back to Obi-Wan’s hut, shot the shit for 50 minutes, and THEN went to Alderran. Honestly, we have one straight 50 minute chunk in Orbitals that could be axed and the screenplay would be exactly the same (actually it would be better because it would be over sooner). That’s not a good sign.

The reason this makes me so angry is because this is Screenplay 101 stuff here. This is some of the first stuff you learn when writing. And so the fact that it’s ignored tells me the writer hasn’t even attempted to learn the craft. I have less sympathy for Amateur Friday writers if they’re not taking the craft seriously. Once again, you’re stepping up to the plate facing a jacked up on steroids Roger Clemens in his prime. You better have spent as much time as possible learning the difference between fastballs and curveballs and sliders before you grace that batting box.

Another Screenplay 101 mistake is that every character in Orbitals talks EXACTLY THE SAME. This is probably the number 1 telltale sign that you’re dealing with a new writer. Everyone here uses “fuck” in equal disparity, meaning nobody sounds unique. All the conversations have the exact same rhythm. And worse, they are exactly the same scenes repeated over and over and over again. The parents want to have sex. We get it. We don’t need 13 scenes in a row telling us that, specifically since having sex has nothing to do with the plot.

And the scenes themselves are like 10-15 pages long. The average scene is supposed to be 2-3 pages long. A “long” scene is considered 5 pages. And you should only have a few of those in your script. 10-15 pages is a lifetime for a scene. There’s a moment in Orbitals where the characters sit down and watch The Shining for five pages, get in an argument, and then have another 5 minute scene talking about watching The Shining and getting in an argument! I don’t even know where to begin with that. Why are we wasting five pages of a screenplay with our characters watching a movie???

There’s no structure here. There’s no conflict. There are no stakes. There’s no urgency. The characters are all the same. The dialogue is repetitive. The story repeats itself. The script basically ignores every good storytelling tenet in the book. And again, this is more a condemnation on the writer for thinking it’s easy than it is on the writing itself. I feel that if John actually studied the craft, read a few books, learned the basics, mapped out a plot ahead of time instead of making it up as he goes along, he could come up with something a thousand times better than this. But this is all we have. And it’s a great reminder that this craft is a lot harder than everybody thinks it is.

Script link: Orbitals

[x] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Readers have strong negative – often angry – reactions to scripts like this because we’re pissed that the writer actually made us spend 2 hours of our lives reading something that they scraped together in a couple of weeks between Modern Warfare and World of Warcraft sessions. You’re going up against veteran screenwriters who know ALL the tricks in the book. Who know how to mine emotion on the page so that they already have the reader in the palm of their hand by page 5. You’re going up against people who are getting professional feedback from producers and agents, then going back and fixing their mistakes until there are no mistakes left. You’re going up against people who are not only pouring over every scene in their screenplay, but every *sentence.* Every *word*. You’re going up against writers who can attach Robert Pattinson or Leonardo DiCaprio to their screenplays. That’s your competition. That’s why you have to be perfect . Every writer loves that fever draft you shoot through in a couple of weeks. But believe it or not, that’s the easy part. The real work comes afterwards. In the rewriting. If you’re not willing to make that commitment, this business isn’t for you.

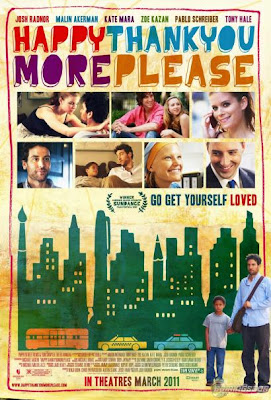

I LOVED the script for HappyThankYouMorePlease. Here’s my old review to show you how much. I loved the weird story. I loved the unique characters. I loved having no idea where it was going or where it would end up. But most of all I loved the writing. It’s rare that I slow down just to admire the skill in which a writer puts his words together. But I did here. And my neck still hurts from the whiplash I experienced after realizing that “that guy from How I Met Your Mother” wrote it.

Needless to say, I was interested to see what Josh Radnor was getting himself into, since he was both directing and starring in the film. The cast he lined up was good, including super-hottie Kate Mara, super duper hottie Malin Ackerman, and super duper uber hottie, Tony Hale (from Arrested Development of course). But man, after finally watching the movie the other day, I can’t tell you how disappointed I was. It was nothing like the movie I imagined while reading the script, and it jolted me into lesson mode. Because I love screenwriting (and screenwriters) so much, I sort of illogically cling to this falsehood that a great script is indestructible. That there’s no way to screw it up. Well, I have been proven wrong, and it’s time to figure out why. Folks, here’s how easy it is to turn a good script into a bad movie.

DIRECTING IS HARDER THAN IT LOOKS

One of the easiest ways to get your script made is to direct it yourself. However, that doesn’t mean it’s easy. Anyone can set up a camera. But it takes knowledge and vision to be a director. The directing in Happythankyoumoreplease was, for lack of a better word, basic, as if Radnor had just completed his first year at film school and couldn’t wait to show the world what he’d learned. From the opening low-angle wake up sequence (I think low angles are the first “exciting” shot you learn as a filmmaker) to the outrageous overuse of close-ups. You’d think that New York consisted solely of big heads and bigger smiles had you only seen the city through Josh Radnor’s eyes. Haters gonna hate on Garden State, but all you have to do is watch these two movies back-to-back to see the difference between someone who has vision and someone who just got their first camera the day before production began.

BLOCKING

Piggybacking off that, no one ever moved in this movie. Except for the outside shots where Radnor and the boy walked around, every scene had two people standing or sitting while we cut back and forth between them. It was as if Radnor had walked into a wax museum and simply started taping pretend conversations between statues. This is a good lesson for screenwriters. Try to have your characters DOING SOMETHING in a scene besides just talking to one another. Have them cleaning or setting up their new TV or taking the trash out. We talk a lot about making your character ACTIVE. Extend that concept to individual scenes. Make them ACTIVE in the moment. Brownie points if their actions reveal more about their character.

THE COUPLE OF DEATH

Oh boy. When I read this script, the one plotline that wasn’t up to snuff was the “Should We Move To L.A. or Not” couple. I thought it worked in script form, but in retrospect that may have been because I could skim through those scenes and get to the other stuff faster. Onscreen, there is no escape. The couple’s whiney repetitive disagreements become all the more whiney and repetitive because you HAVE NOWHERE TO HIDE. You’re stuck listening to them drone on and on and on about L.A. L.A. is bad. L.A. is good. L.A. is bad. L.A. is good. I quickly labeled them THE COUPLE OF DEATH because every time they came onscreen, the movie died. This is a HUGE reminder to make sure EVERY CHARACTER COUNTS in your screenplay. If you have a boring character or a boring couple in your script, rewrite them. Or get rid of them. Or replace them. But whatever you do, don’t leave them in your movie. Or they will kill your film every second they come onscreen.

JOSH RADNOR AS JOSH RADNOR

I get it. All actors are vain. And the guy wants to prepare for his career after “How I Met Your Mother.” Don’t want to end up like Joey or the Seinfeld guys. So from a selfish standpoint, I understand Radnor’s choice to star in his own movie. Still, the number one slam dunk way to ruin a script is bad casting. The wrong actor can kill a character. And Josh was never right for this part. His face is too smiley. He’s too bubbly. I never once bought him as this down-and-out struggling dude. Maybe he does have some suffering in his past, but he certainly didn’t convey that in his performance. If you’re ever in this position, ask yourself, if I was someone else, would I really cast me in this role?

BE CAREFUL ABOUT WRITING YOUNG KIDS INTO YOUR MOVIE

It’s really hard to find good young actors (5-6-7 years old) who can anchor a major plot thread for an entire movie. You can scour Backstage West or Frontstage North or Facebook or talent agencies or wherever. The truth is, finding a kid who can nail a role like this is one step higher than blind luck. The boy who played Rasheen in “Happythankyoumoreplease” wasn’t terrible. But he wasn’t good either. He just said yes and no 50 times and that was it. Kids are necessary to tell certain stories. But beware when writing major roles for 5 year olds. Chances are you’re not going to find that actor.

CONVERSATIONS ABOUT LIFE – DITCH’EM

People. Unless you’re Richard Linklater, limit the “conversations about life” scenes in your movie to 1 per script. And if you really want to do the world a favor, don’t write any at all. There are few things as pretentious and grating as two characters opining about existence and life’s difficulties. I’m sure there are a couple of examples in film history of these scenes working, but I can’t think of any. More importantly though, be aware of WHY you want to write these scenes in the first place. It’s usually because your characters have nothing to do. You need to fill some time. So you think, “Hmmm…I’ll have them discuss, like, life and stuff.” Who then, are our big violators of this deathly mistake in “More Please?” Surprise surprise. None other than THE COUPLE OF DEATH! They have nothing to do. Therefore the writer is forced to give them meaningless dialogue. Always give your characters something to do people, somewhere to be, something to get. By doing so, you won’t need to give them pointless things to say.

MORE MOVEMENT – MORE ACTION – MORE CHARACTERS AFTER THINGS

Building on that, the biggest thing I’ve learned here is just how difficult it is to turn talky scripts into good movies. Talky stuff works on the page because readers love to speed through scripts and if there’s a lot of dialogue, it’s easy to get through faster. But what was so fast and easy on the page becomes slow and plodding on the screen if the actors delivering the line are standing around doing nothing. You need a means to liven things up. Woody Allen is a master at this and the main tool he uses is he always has other things going on in the scene besides two people talking. Maybe there’s subtext (one of the characters likes the other but hasn’t told them yet), maybe there’s an external force pulling at them, maybe there’s another couple antagonizing them. People are always in a state of flux in Woody Allen’s scenes, which adds energy, something sorely lacking in “More Please.”

For example, in his latest film, Midnight In Paris, there’s an early scene where Owen Wilson and his fiance are having lunch with the fiance’s parents, and two old friends of the fiance show up unexpectedly. The scene is interesting because the fiance is trying to balance entertaining two opposing groups who don’t know each other at the same time, never an easy task. In the meantime, Owen Wilson doesn’t get along with the parents and doesn’t like the friends, so he’s trying to stave off any attempts to meet up later with either party, which, of course, is exactly what his fiance wants. That’s what I mean by multiple things going on in a scene. It’s complicated. It’s dynamic. And it’s not just two people standing across from each other talking about the meaning of life, which are some of the most difficult scenes to make interesting EVEN IF you’re a great writer.

I hope there’s something in these observations that helped you. But if not, here’s one last tip. Please, never, ever, ever, ever, ever, ever, EVER write a COUPLE OF DEATH into your movie.

Genre: Western (TV pilot)

Premise: In 1865, a town physically moves across the frontier, following the construction of the Transcontinental Railroad.

About: Hell on Wheels is an AMC show set to debut either this year or early next year. Tony Gayton won the Jack Nicholson Screenwriting scholarship at USC, where he attended, over a decade ago. After graduating, he worked as a production assistant for John Milius. He also wrote the Val Kilmer film, “The Salton Sea” as well as writing (with his brother), “Faster,” last year’s film starring The Rock. Here’s an interview he did with his brother leading up to the film’s release.

Writers: Tony & Joe Gayton

Details: 44 pages – 8/3/2010 draft (This is an early draft of the script. The situations, characters, and plot may change significantly by the time the film is released. This is not a definitive statement about the project, but rather an analysis of this unique draft as it pertains to the craft of screenwriting).

AMC has its shit together. In a world where creativity is shunned, this channel is one of the growing few that is willing to take chances. Okay okay, I admit it. I stopped watching The Killing after three episodes (I sensed they were basking a little too comfortably in their “anti-procedural” proceduralness. Sooner or later, you gotta start answering questions – I still haven’t seen the finale but I hear it proved me right. What did you guys think?). But overall, you gotta give it to AMC for not creating Law & Order CSI 50.

Friday, we dissected the amateur period piece, The Triangle, which afterwards left serious doubts as to whether it’s possible to make period pieces exciting for a modern-day Twitter-centric audience. But Hell On Wheels proves that with some good old fashioned story sense, an eye towards milking the drama, and an infusion of as much conflict as possible, you can make any story exciting.

It’s 1865. The Civil War is over. Lincoln is dead. America is trying to get back on its feet. But they’re having a rough go at it. Each side is bitter about how things went down (particularly the, um, losing side) and they’re not hugging it out saying “good game.”

Hell On Wheels starts off the way every show should start off, with a good scene. Bring us in right away and never let go dammit. A local soldier goes to a church to confess the sins he perpetrated during the war but seconds later the priest he’s confessing to puts a bullet through his head. Or who we thought was a priest. This is Cullen Bohannon, an ex-Confederate soldier with revenge on the brain. Something really bad happened to this man during the war. And now he’s going after the Union soldiers who did it, one by one. This is the second to last. He’s got one more to go.

Cut to the building of the Transcontinental Railroad, the thing that’s going to change America. The thing that’s going to connect the East to the West. The railroad is being built by a dishonest tyrant of a man named Thomas “Doc” Durant. Doc could care less about America’s noble pursuit to expand. All he cares about is making this construction go as slowly as possible so he can milk the government for every penny they’ve got.

This is where Cullen is headed. And where many people are headed for that matter. Building a railroad requires a lot of work so, obviously, they need workers. Once there, we meet a few more of the major players. There’s Elam, a black man dealing with the ongoing testiness of men who still don’t believe he should be free. There’s Joseph Black Moon, a Cheyenne Indian who’s acting as a sort of intermediary between his people and the railroad workers. There’s Daniel Johnson, a mean son of a bitch who carries a hook for a hand. There’s Lily and Robert, a married couple who are dealing with Robert’s deteriorating health. As the train moves further and further into Cheyenne Country, and the threat of violence with the natives becomes more of a reality, he’s begging her to go home where it’s safe, but she insists on staying by his side.

And then of course there’s the biggest character of them all, the thing that sets the show apart from everything that’s come before it, the town itself. “Hell On Wheels” is a moving town, a series of makeshift tents that trudges along the frontier, following the expanding railroad. This was my favorite aspect of Hell On Wheels because I’m always asking, “How do you make a Western different?” They’ve done just about everything already. Not only is a moving town unique, but it brings up a lot of opportunities you’d never get to see in a traditional Western (for example, the concept of moving further and further into dangerous Native American territory). In other words, it’s not just a gimmick.

That combined with the intriguing main character, Cullen, who we’re not sure if we should like or fear, gives this pilot an edge that you just don’t see in movies or TV shows. Out of all the Westerns I’ve seen or read in my life, Brigands comes first. And this would be second.

So what does it do right? A lot. There’s conflict everywhere you look in Hell On Wheels. Cullen seeking revenge against the men who ruined his life. A Hitler-esque railroad developer who challenges everyone he meets. A character on the brink of death from disease. The looming threat of a war with the Cheyenne Indians. Racial tension on the building lines. That’s why this teleplay is so damn great. There isn’t a single scene where something isn’t clashing with something else (or leading up to a clash). We’re never bored here.

Which leads to the next thing. In a TV pilot, you want to set up/allude to as many major character conflicts as you can. You want the audience saying, “Hmm, I wonder how that’s going to play out?” Or, “I wonder how that’s going to evolve.” When someone finishes watching that first show, you want them pissed off that the next episode isn’t on RIGHT NOW. So here, when we learn that Cullen’s final mark is here in this town, we can’t wait to see how he’s going to get to him. When we see the Cheyennes discussing how they’re going to treat this invasion onto their land, we can’t wait to see if they’re going to move in. We can’t wait to see how Joe, the Cheyenne who’s in the middle of it all, is going to react. Will he choose his people? Or his new friends? And of course we can’t wait to see the unique machinations of this moving city, this “Hell On Wheels.” There are so many intriguing threads here.

I loved the little touches in Hell On Wheels as well. Like when Durant gets pissed at his builders for trying to build the railroad straight. “What the fuck are you doing?” he asks. If you build the railroad straight, you complete the railroad faster, which means I don’t get paid as much money. So he insists they make it curvy. This had me wondering, is this really what happened? Were our ancestors so corrupt that still to this day we have inefficient railroad paths twisting through our country? I love when screenplays break that fourth wall and make you think.

You know, I recently watched the abysmal pilot for the Spielberg produced TNT series, Falling Skies. And I found myself comparing the two scripts, wondering why a script about the old west, something I have little interest in, was so much better than something about aliens, which is a subject matter I love.

The answer came quickly. There wasn’t a single character that stuck out in Falling Skies, that popped off the page. None of them had anything unique or interesting going on. Everything about their existence, their goals, their desires, was humdrum, basic, generic. But here, in Hell On wheels, you had characters enacting revenge, characters torn between two sides, lovers in denial about impending death, corrupt dictators. One of the sure signs of a good screenplay (or teleplay) is that you REMEMBER the characters afterwards. And the way to do that is to give them real lives, real problems, real fears, real conflicts. Hell on Wheels had that in spades, and it’s the reason it’s so damn good.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[x] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Create looming conflicts. Conflict is not just about the right now. It’s not just about two characters who don’t like each other or don’t agree on something in the moment. It’s about the future. It’s about hinting at conflict that is to come. When you do that, you create a powerful force – anticipation. If we’re anticipating an event, a future showdown, we’re more willing to keep watching. The two instances that really got me here were the looming clash with the Cheyenne Indians and Cullen’s last mark. I needed to see those two things resolved. Pack your pilot with a handful of these and people will want to tune in for the next episode.

Genre: Period

Premise: New York, 1910. When a group of starving female workers strike against the most powerful garment manufacturer in America, they turn to a clever young reformer who must lead them in a fight for human dignity before winter — or worse — takes their lives. Based on actual events.

About: Every Friday, I review a script from the readers of the site. If you’re interested in submitting your script for an Amateur Review, send it in PDF form, along with your title, genre, logline, and why I should read your script to Carsonreeves3@gmail.com. Keep in mind your script will be posted in the review (feel free, however, to use an alias and fake title).

Writers: Patrick McNair & Eric Thompson

Details: 115 pages

This is going to be one of the tougher reviews I’ve ever had to write. Because I know Eric is a big fan of the site and he’s been pushing me to review this script for a long time. So I really really wanted to like it. That’s what kind of sucks about Amateur Friday. Is that the people who send their scripts in are usually the biggest fans of the site. And the last thing I want to do is tear their baby apart. But part of the journey of screenwriting is learning to take criticism and using it to come back bigger, faster, and stronger with your next script. And that’s going to be the theme of today’s notes.

Of all the genres you have to choose when writing a spec, a slow-moving period piece puts you in the worst possible position to succeed. So normally I BEG – literally get down on my knees and BEG – writers not to write period pieces. Production company pays you 50 grand to rewrite one of their own period piece properties? Yeah, do that. Spend 1-2 years of your life writing a period piece from scratch when you don’t have any pre-existing knowledge from agents or producers that they are looking for this kind of script? Honestly? It’s career suicide. Except before your career’s even started. It’s pre-emptive career suicide.

And the thing is? Today’s writers seem to know this. This is what Eric had to say to me in his e-mail query: “My writing partner and I messed up. Royally. We should have written a comedy about immature men or a taut thriller about a victimized woman in perpetually wet clothing. We should have written about things that blow up. God help us, we should have written a coming-of-age teen dramedy instead of writing what we did. We… we wrote a period piece. I know, I know, but that’s not even the worst of it. *Sigh* There are multiple protagonists (and half of those blend into each other), it would cost a fortune to make and no one would go see it because it looks to be about “issues.” Hell, it doesn’t even have a dog. You get the idea.”

That he acknowledged the difficulty in writing this type of screenplay gave me confidence that he knew how to make up for that somehow. That he’d need to write a dramatically compelling conflict-filled rip-roaring story with amazing characters and intriguing plotlines. That was my big hope when picking up The Triangle. A hope that was dashed pretty early in. The Traingle is so dense with characters, so information packed, so heavy with words, that by page 50 my attention was shot. I’d spent so much energy trying to keep up with all the characters and all the situations, all while nothing exceptional or interesting was really happening, that by the middle of the script I was toast. I felt the way you feel after cramming for a test all night. At a certain point, the words on the page just stop making sense. So if my summary is a little off, I promise you, I did my best.

It’s 1909. Immigrants are arriving in New York. The Triangle Shirtwaist Company is renowned for taking a lot of the poor female Jewish immigrants from these boats and putting them to work for ridiculously low wages and under less than stellar working conditions.

Frances Perkins, an educated woman from Philly, is looking to better the conditions for these women and women everywhere. Though because this is a man’s world from the top down, she’s encountering a lot of resistance.

Meanwhile, the girls at the Shirtwaist Company are sick of being treated like dogs and decide to unionize. But Max Blanck, the powerful and heartless Russian owner of the factory, tells his workers that if they join a union, they will lose their jobs.

The girls strike anyway, and Max ignores them, simply hiring new fresh-off-the-boat girls to take their places. To make matters worse, a band of wild hookers attack our striking workers for seemingly no reason. The Shirtwaist workers are sent off to jail, where they realize the hooker attacks were a scam perpetrated by Max to stave off the bad publicity he was receiving from the strike.

We keep cutting back to Frances, who’s slowly making her way through a gaggle of politicians, getting closer and closer to seeing her “Improved Working Conditions” bill passed. But it looks like it’ll be too little too late.

Max’s deplorable working conditions end up causing a giant fire and because one of the key exit doors was locked, over 100 women were burned alive trying to get out of it. A tragedy that could’ve been avoided, but because of arrogance and a basic ignoring of human rights, many people died instead.

When you give a script to somebody, you’re making a deal with them. You’re saying, “You give me two hours of your time and I’ll entertain you for those two hours.” That’s what people receiving your spec script are looking for. They’re looking to be entertained. When you give these same people a period piece, the phrasing of that deal changes. You’re now saying. “Look, I know it’s a period piece. I know most period pieces are really long and really dense and really dull. But I promise you, this isn’t going to be one of them..” But it doesn’t matter. They’re already on guard. Period pieces are always the hardest screenplays to read and for that reason, readers hate them. Here’s a list of six things readers are terrified of encountering when they read a period piece.

1) That there will be an endless amount of characters they have to remember.

2) That the story will move at a glacial pace.

3) That they’ll need to memorize a bunch of time-specific details in order for the story to make sense.

4) That the writer cares more about the history of the event than how to DRAMATIZE the event.

5) An unfocused narrative that jumps around to too many disparate story threads.

6) Thick never-ending chunks of text.

The Triangle violates pretty much every one of these, handicapping its story so severely that it’s basically reader kryptonite. Let’s take the first fear, character count, and see where The Triangle falls.

Sonya

Max

Issac

Abe

Eva

Rachel

Kalman

Vincenza

Sylvan

Al

Thomas

Clara

Bernstein

Cantilion

Amos

Bob

Rose

William

Mrs. Lansner

Phillip

Mildred

Henreietta

Mary

Leonora

Gompers

Gable

Edmonsson

Kesey

Alva

Anne

Rafal

There’s your character list for The Triangle. Okay, I’m going to say this next part as kindly as I can.

COME ON!

One of the jobs of a writer is to know how much information a reader is capable of handling. Readers are not geniuses. They are not human computers. They do not keep assistants on hand to write down and recite back character names when they can’t remember someone. I mean writers have to be honest with themselves. How is reading something enjoyable when every two pages the reader has to stop, check their notes, recall the character, then go back to reading again? And that’s IF they decided to keep notes in the first place. If your reader is not taking notes? This script is toast by page 20. They will not remember anyone and therefore every single scene will be confusing. There is no way to save a screenplay once that happens.

The idea in any screenplay is to make us care about the characters so we care about what happens to them. But how are we supposed to care if we only spend a couple of minutes with each character every 20 pages or so? How do we get to know these people? Huge character counts KILL a screenplay because the reader can’t latch on to anyone. Titanic (which I’ll reference here a lot since it’s both a period piece and has a tragic ending, like The Triangle) had a big character count but 90% of the time we were with Jack or Rose. The biggest character The Triangle focuses on is Frances, and she’s not even involved in the fire! Guys. You have to write smart! Limit your character count to JUST the characters that matter. Keep us with the most interesting of those characters 70% of the time AT LEAST.

Next thing I worry about with period pieces is glacial pacing. Let’s recount what happens in the first half of The Triangle. Women hate their job. They want to unionize. They go on strike. Another woman lobbies the senate for better working conditions. That’s pretty much it. In screenplays, INTERESTING THINGS NEED TO HAPPEN FREQUENTLY. Nothing really happens in The Triangle until the fire. It’s just a bunch of people talking about unions or getting bills passed. The one memorable moment is the hookers attacking the strikers and that moment was so strange (the image itself is actually quite comical) that it didn’t play the way it was intended to.

You have to keep us entertained. Even if it’s a “slow-moving” period piece. Things need to HAPPEN. It would be like if Titanic, instead of focusing on Jack and Rose, focused on the politics of how the Titanic sunk.

This led right into problems 3, 4 and 5. The Triangle is basically a history book. It’s a retelling of events. Which is not what movies are about. Movies are about finding drama in situations, not recounting said situations. You do this with your characters. You focus on them and then you tell the story of the historic event through their eyes. Is Titanic about how the ship sunk? No. It’s about two people falling in love. THAT’S what we remember.

What The Triangle needed was two or three characters we could latch onto who were experiencing some sort of conflict with each other. It doesn’t have to be a love story. It can be a brother and sister. A mother and her daughter. Any two people that have some unresolved issue. Make us care about that issue and we’ll end up caring about the building they work in that later catches on fire. The unions and striking and lobbying should all be secondary to that relationship. Like, WAY SECONDARY.

Outside of that, this script just needs a great big shake-up. It needs more energy. It needs more surprises. It needs more drama. It needs more conflict. It needs a quicker pace. It needs more humor. It needs more edge. It needs more interesting situations. It needs to be focusing on a core group of people. One thing I see with a lot of period pieces is that the writers who write them LOVE history so much, that that’s all they focus on, is the history of the event. Giving us the cold hard facts. There’s a specific line in The Triangle where I officially gave up on the script being able to entertain me. Here’s the line, which comes on page 39: “Let us know as soon as you possibly can if you would be willing to form an Employers Mutual Protection Association….”

This is indicative of the mindset of the script. We’re focusing on “Employers Mutual Protection Associations.” I don’t care if you’re Aaron Sorkin. There is no way in the world that you can make “Employers Mutual Protection Associations” interesting. There may very well have been an Employers Mutual Protection Association during that time. But readers don’t care about that.

Your job is not to retell history. Your job is to DRAMATIZE THE EVENT. In Titanic we have Jack saving Rose from suicide, we have them sneaking around behind her fiance’s back, we have a man looking for the biggest diamond in the world, we have classes clashing, we have a mother forcing her child to marry a man she hates to save the family, we have forbidden love. THAT’S how you dramatize an event. Anybody can read up on the Titanic and give you a play by play of how it sunk. What I want to know about is the PEOPLE who were victims of that mistake.

And that brings us back to the character count. This is where The Triangle burned itself. Remember, if you don’t have a few core people the audience loves/wants to root for, every single thing that happens from that point on doesn’t matter. Doesn’t matter if it’s the most interesting plot in the world. We don’t care about the characters? We don’t care about the world they live in. When you blanket your script with an endless character count, you prevent the reader from latching on to anybody. If there’s a priority of things to fix in this script, that would unquestionably be number 1 on the list.

I realize these notes are harsh but one of the best things a reader can do for a writer is tell him when something isn’t working. So many writers just write in circles cause they never get any real feedback. In the few instances that a prodco agrees to read their work, they often never hear back from them, or get a stock “pass” e-mail, leaving them with no idea what’s wrong with their screenplay. Do they write another draft blindly? Do they guess what’s wrong? It’s an agonizing process.

In order for The Triangle to work, it would likely need a huge rewrite that focuses more on the characters and less on the mundane details of unions and strikes. And the problem is that even if Eric and Patrick nailed that rewrite, they’re still trying to pitch producers on a period piece, which means they’re getting about 1/10 the reads that you’d normally get (and you’re normally not getting many reads). There’s nothing wrong with the writing here. In fact, I don’t recall a single typo. If you read this script, you can tell the writers put a lot of time and effort into it. But it’s so difficult of a sell. And I know how nice of a guy Eric is. I wouldn’t try to break in with this script. If you really really really love the subject matter? Save it for when you become big time. But trying to break in with this is like trying to walk into North Korea draped in an American flag. It’s just too damn risky.

Script link: The Triangle

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Don’t write a period piece on spec. Just don’t do it. It really is suicide. The only exceptions are if you’re doing it for practice or you don’t really care whether you succeed or not. Where do all the period piece movies come from then? They come from pre-existing properties. They come from book adaptations. They come from in-house production company ideas. They rarely, if ever, come from spec scripts. If you still refuse to ignore this advice, then at least make your period piece exciting. Limit the time frame. Add revenge to the mix. Keep the story simple. Create impossible odds for your hero. Give us a COMPELLING SCENARIO. For example, Odysseus sold a couple of years ago and that script met all of that criteria. I just hate to see writers waste their time on impossible pursuits. You’ve already chosen the most competitive field in the world. Why voluntarily make it harder for yourself?