Search Results for: F word

Genre: Horror

Premise: (from IMDB) Set in a medieval village that is haunted by a werewolf, a young girl falls for an orphaned woodcutter, much to her family’s displeasure.

About: David Leslie Johnson’s script “Orphan,” made a lot of noise when it was picked up a couple of years ago. Even though it didn’t make a huge dent in the box office, I thought it was pretty good, especially the bizarre twist ending which I wouldn’t have predicted had you given me a hundred tries. Johnson has a very enviable backstory. He was lucky enough to have been mentored by Frank Darabont (working with him on both The Green Mile and Shawshank). The Girl With The Red Riding Hood stars Amanda Seyfried, Gary Oldman, Virginia Madsen, Shiloh Somebody and Julie Christie. Catherine Hardwicke, the director of the first Twilight film, is directing.

Writer: David Leslie Johnson

Details: 120 pages – revised first draft – April 16, 2009 (This is an early draft of the script. The situations, characters, and plot may change significantly by the time of the film’s release. This is not a definitive statement about the project, but rather an analysis of this unique draft as it pertains to the craft of screenwriting).

You say I don’t do horror. A pox upon you! I do horror. I’m doing horror right now knuckleheads. I heeded all your nasty e-mails and death threats and am finally giving you want you want. Okay, none of that is true. I’m only reviewing this because I hated the other script I was going to review (“36”) and couldn’t muster up the energy to review it.

But here’s the truth. I WOULD review more horror IF there was more horror to review. It seems like every horror script that comes down the pipeline is either a shitty remake or a sure-to-tarnish-the-original sequel. All I’m asking for is ORIGINAL HORROR. Something fresh and unique, like Johnson’s previous effort, Orphan. Any spec sales that fall under that category, let me know, cause I’ll be happy to read them.

So, The Girl With The Red Riding Hood is a “gothic” reimagining of that famous fairy tale, “Little Red Riding Hood.” Johnson has been saddled with the difficult task of fleshing out this 5 minute story into 2 hours. The results are, I suppose, solid, but since this isn’t really my thing, I had a hard time getting into it.

It’s 1324 in a French village and 17 year old Isabelle is having a secret romance with fellow villager, and brooding hunk, Peter, who works for her father. However, Isabelle is told that she’s being married off to a man named Henri to settle a debt between her and Henri’s family. Don’t you just love the old days? Have a problem with me? Here, take my daughter.

Isabelle is devastated but she and the rest of the village have bigger issues to battle. A rogue wolf has been terrorizing the town for decades and while it hasn’t killed any of them recently, signs point to that changing soon. Wolf be hungry. So scared are the villagers that they send for a “Witchfinder General” by the name of Solomon. I’m, of course, wondering the same thing you are. Why would you hire a witchfinder to find a wolf? (see how bad I am at reviewing horror?)

Well Solomon, a very serious individual, is too busy being pissed off to care what I wonder. He explains that this isn’t a wolf terrorizing their town. It’s a WEREWOLF. Solomon knows all about werewolves, you see. He’s killed one before. A werewolf that ended up being his own wife! By the name of Bella! Okay, I’m kidding I’m kidding. She wasn’t named Bella.

Anyway, Solomon and his men lure the werewolf into town, where it becomes preoccupied with Isabelle, and after finally getting her alone, it TALKS. Yes, this werewolf can talk. It wants Isabelle to come off with him. Apparently it’s not a very smart werewolf or it would know that people don’t run off with werewolves! Unless of course, the father orders them to. Then it’s okay.

Afterwards, Solomon realizes that the werewolf is not some rogue wolf at all, but that it lives here, in the village. Someone, one of them, is the wolf! The town naturally starts freaking out, and the mystery is on. Which one of them is the wolf?? And will it kill them all?

Okay so, disclaimer time. This isn’t my thing. Doesn’t matter if this were Oscar-worthy writing, I probably wouldn’t like it. Having said that, it’s a solidly executed script. I admit that the one area of writing that intimidates me the most is swords & shields period pieces. Anybody who can write dialogue for a time they did not exist in, where people spoke in a rhythm and a vocabulary as familiar to us as Japanese, I have a lot of respect for. And I think Johnson did a nice job with that.

I also thought he did a good job keeping the story fresh. There’s little twists and revelations here that throw the story in another direction just when it needs it. We have a devastating family secret that’s revealed about Isabelle’s sister. We have Solomon showing up to add some ass-kicking to the mix. We have a wolf who’s able to speak. All of that really kept you on your toes.

But if there’s one type of story I don’t respond to it’s the “Let’s wait here and die,” story. When you throw a bunch of characters into a location and they just wait for the bad guys to show up – that’s no fun for me. It’s not that you can’t make it work. I just like when my characters are active, when they have plans. In Aliens, they’re not just waiting for the aliens to kill them. They’re formulating a plan to get the hell out of there. Johnson’s able to infuse the characters with some proactive moments, but in the end, they’re still just a bunch of people waiting around.

This reminds me. Didn’t the original Red Riding Hood walk through a forest? Wasn’t that the big set piece of the story (did they have set pieces back in the fairy tale days)? That she was going somewhere and the wolf cut her off? I guess I kept waiting for this long journey she would have to take through the woods, knowing that the wolf was out there, and the ensuing suspense that would come from whether she would make it or not. Not a huge deal but it seemed like that kind of scene could have some potential and it was a part of the original story so I was confused as to why it wasn’t there.

Despite this not being my cup of tea, I can see it working. The image of an innocent girl in a red riding hood is so iconic that I can’t imagine the trailer not being cool. The question is, does the public’s demand to have their werewolves with ripped abs and predetermined teams make a tale like this obsolete? We’ll have to wait and see.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Hollywood likes things they know. They like to get behind stories the public’s heard of before because then they don’t have to spend a billion dollars educating them on it. You and I have heard of Red Riding hood, so there’s a familiarity factor there. There’s no familiarity factor with “Blue-shoed Thomas” or “The Old Man With The Green Jacket.” For that reason, fairy tales are a great place to look for stories. Nobody owns the rights to them, and many are well-known. The trick is to throw a unique twist on the tale to make it fresh. Remember how cool that video game “Alice” was? They simply threw Alice in Wonderland into the horror genre. What about taking the Three Little Pigs and turning it into a modern day comedy starring Jack Black, Jonah Hill, and Phillip Seymour Hoffman? I’m only half-joking! But seriously, if you can find a cool spin on one of these tales, run with it. I see a lot of new writers get noticed this way.

Genre: Thriller/Drama

Premise: (from IMDB) Based on a true story, a mountain climber becomes trapped under a boulder while canyoneering alone and resorts to desperate measures in order to survive.

About: The buzz hit early on this script, highlighted by the fact that there will be an entire hour without a shred of dialogue. One of the best directors in the business, Danny Boyle, just finished the film. The script is written by his Slumdog Millionaire collaborator, Simon Beaufoy. James Franco plays the lead role. You can learn more about the real-life story here: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aron_Ralston.

Writer: Simon Beaufoy.

Details: 83 pages – April 1, 2010 draft (This is an early draft of the script. The situations, characters, and plot may change significantly by the time of the film’s release. This is not a definitive statement about the project, but rather an analysis of this unique draft as it pertains to the craft of screenwriting).

A question I hear a lot is, “Have you ever read a bad script that became a good movie?” The answer is no, I have not. But the ones that come closest are usually from directors like PT Anderson, Malick, Nolan, Mann, and Sofia Coppola. These helmers have such a powerful and unique style that the story almost becomes secondary to the filmmaking. For example, one thing I loved about Inception was the score. That deep trombone like bass that cycles throughout the film unnerved me in a way a story turn or a character revelation could never do. These kind of filmmaking-specific nuances will never substitute for a good story, but sometimes they can come pretty close.

127 Hours may very well be one of those films, because as a script, I didn’t think it was very good. It isn’t bad. It’s just…predictable.

For those cinephiles who saw “Into The Wild,” a few years ago, Sean Penn’s directorial effort about a man who sells everything he owns and heads for Alaska, Aron Ralston is very much like the character in that film, Christopher McCandless. He’s an adventurer, an outdoor enthusiast, a lover of nature. And like McCandless, he does everything exclusively by himself.

This is exactly how we meet Aaron, heading down to Blue John Canyon on his bike – alone. Once he reaches the desert, he locks up and sprints towards the canyon.

There he runs into a couple of girls, Kristi and Megan, who feel a bit like filler. The problem with writing a script with only one character is that you only have one character to develop. In other words, you don’t need a lot of space. But in order to get the page count up to feature length, you have to put something there, and I’m guessing that’s why these two are in the script (from what I understand, Aron *did* meet them in real life).

So the girls appear, have a few conversations with Aron telling us what we already know, that Aron rides life solo, then scram. But not before telling him about a party they’re going to 20-some miles down the road. You can’t miss it, they say. There’ll be a gigantic Scooby-Doo balloon swaying in the wind.

Later, he makes his way to a canyon/cliff area, starts running around and exploring, accidentally dislodges a boulder, gets chased Indiana Jones style, squeezes out of the way at the last second, but is unable to get his arm out of the way in time. The boulder catches it against the rock. Aron is shocked when he realizes…he’s stuck.

Thus begins Aron Ralston’s 127 hours of hell.

127 Hours uses three devices to keep us entertained – Video diaries which Aaron leaves on his video camera, flashbacks to his old girlfriend, and a series of hallucinations. Interspersed throughout these moments are Aron trying to figure out what to do. I don’t think I’m spoiling anything here since this is a real-life story, but eventually Aron realizes that the only way he’s going to survive is if he cuts his arm off – a process made difficult by the fact that he only has a Swiss army knife. And not even the real thing either. A cheap Chinese knockoff.

Essentially 127 Hours is a character piece about a man who realizes what being alone is really about. There’s a difference between the kind of alone where you get to pick and choose when you hear others’ voices, and the kind of alone where you don’t hear any voice but your own. As days dissolve into one another, Aron comes face to face with this reality, and begins to appreciate and understand how desperately all the people in his life have tried to connect with him.

This raises a bigger question: If Aron somehow gets out of here, will he finally look to bring these people into his life?

But if I’m being honest, it was hard to root for Aron. This might seem like an odd declaration, but I don’t have sympathy for people who do stupid shit. You read in the paper, “A freeclimber falls 3000 feet to his death.” You know the first thing that comes to mind when I hear that? “You probably shouldn’t have been climbing 3000 feet in the air WITHOUT ANYTHING TO SUPPORT YOU!” I mean if I ever start juggling chainsaws in Vegas and accidentally cut myself in half, I fully expect anybody reading an account of my ordeal to reply: “Serves you right moron.” I mean Aron isn’t cliff-diving into lava here, but running around the desert and climbing mountains with no one else around and without telling anybody where you are is a pretty stupid thing to do. So I just wasn’t onboard with him from the get-go.

I was also never surprised by this screenplay. As soon as Aron got stuck I thought, “There’s three things he can do here: talk to the video camera, go into flashbacks, and hallucinate.” Sure enough, that’s exactly what happens. And while I somewhat enjoyed Aron exploring his connection issues via flashbacks and hallucinations, in the end these scenes were too repetitive to fully keep me interested. At a certain point I was like, “Let’s cut off the arm already.”

Another unfortunate aspect of this story is that we know the ending before the film starts, draining the script of a good portion of its suspense.

Despite all this, I still think 127 Hours can be a good movie. Boyle is a filmmaker that plays in the same sandbox as Nolan, Mann, and Malick, so he obviously saw something worth getting dirty for. If I had to bet, I’d say he was drawn to the hallucinations, which become a huge part of the second half of the film. Visually, these are extremely weird and powerful (I imagine the huge floating Scooby-Doo balloon in the middle of the desert will be the “what the fuck” trailer image that sells a good share of tickets) and if there was ever an opportunity to explore the limits of your imagination, no-holds-barred hallucinations would be a great start.

But if it will be enough to make up for a rather ordinary story, I don’t know.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: One of the reasons we go to the movies is to see characters try and overcome the same issues we’re trying to overcome in our own lives. The exploration and eventual conquering of these “flaws,” when done right, can be the most powerful part of your story, because it gives us hope that we can conquer our own issues. There are a few character flaws that consistently work well, and one of them is the one Beaufoy uses here – Aron’s refusal to connect with the world. I don’t know what it is, but when we see someone who refuses to connect with others, we instinctively want them want them to connect with others. I’m reading The Girl With The Dragon Tattoo (the book, not the script) and Lisbeth Salander has this exact same flaw. She’s so disconnected from everyone and everything that we pine for her eventual transformation. We want her to initiate a hug, trust someone, open up to a friend. And the further she pulls away, the more desperately we want to pull her in.

And Roger makes three! This week we have an unprecedented THREE impressive scripts, one that even joins the coveted Top 25. That just doesn’t happen. Especially lately. The other two scripts are…ehhh, not very good. As for where to find it, this script has been around for forever (get it, cause it’s immortal?), and I know plenty of people have it. Maybe they’ll pop up in the comments section. Anyway, here’s Roger with his review!

Genre: Supernatural comedy

Premise: (from Hollywood Reporter) A slacker discovers that he is the latest in a long line of immortal warriors, a la Highlander, and must fight to achieve his destiny.

About: “Jeff the Immortal” was on 2007’s Black List and it was picked up the same year by Universal. From Rope of Silicon: “Apparently Bishop got the idea for the film after watching Highlander, the 1986 fantasy tale starring Christopher Lambert and Sean Connery, and wondered what he and his buddies would do if they got such powers.” Bishop was a writer on the Drew Carey Show and is also the author of Hardly Working at Relationships: The Overachieving Underperformer’s Guide to Living Like You’re Single When You’re Not. Bishop is also the writer on the American adaptation of the German comedy, Night of the Living Dorks.

Writer: Chris Bishop

Hehehe.

Like I do with Terry Pratchett novels, I made that sound a lot while reading this script. And, that’s kind of what this script reads like. Imagine if Terry Pratchett was an American screenwriter who was obsessed with arcade games like Dragon’s Lair and musicals like Wicked, then imagine him writing a script that parodies the Russell Mulcahy cult classic, Highlander, and you’ll have a pretty good idea of what to expect from “Jeff the Immortal”.

I haven’t seen Highlander, Rog. What’s this sucker about?

Jeff Seagal has spent a decade or so just hanging out, and now he finds himself on the cusp of thirty, anxious to marry his girlfriend Scarlet. Jeff used to want to be a chef, and in fact he even got into culinary school once-upon-a-time, but he could never afford the tuition. Instead, he finds himself working at the Bullseye Department store, a job that requires him to wear a nametag. Marrying Scarlet is his attempt to reclaim the American dream of doing something with his life and owning a house by thirty.

When we meet him he’s playing a videogame with his jaded co-worker LaQuinta who warns him that marriage means the end of oral sex, “My Rodney said ‘I do,’ but the rest of the sentence should’ve been ‘n’t eat any more pussy.” Later in the day, Jeff notices a balding heavy-set white dude dressed in sweat pants and a ratty old FUBU shirt peeking at him. Soon after, Jeff is victim to a paper cut. Then, he notices something weird.

He watches the wound heal before his eyes.

When he looks back up, the strange, old dude is gone.

Undettered by LaQuinta’s ominous warning of no more oral sex, Jeff arrives at his home to discover that Scarlet is leaving him. Apparently, she has been cheating on him for months. With the mailman. And then the UPS guy. Then she had a three-way with the FedEx man and the milk man. “Milk man? There are milk men left in America?”

“It’s a dying profession. His name is Logan. I think I love him.”

Jeff goes to a bar with best friend Russ for consolation. Russ’ life is all ice cream and blowjobs. He tries to cheer his buddy up, “Look, it isn’t as glamorous as it seems. I sell RVs for a living. I live with my Great Aunt. I drive a piece of shit yellow Saturn. Sure I’ve had my fair share of notches on the futon, but am I truly happy?” The funny thing is, Jeff realizes that he’s not so torn up about Scarlet. He realizes he’s been dating a bitch who hocked all his DVDs, cleaned out his bank account and slept with every dude who wore a Flyers jersey.

When they get back to Russ’ Great Aunt’s house, they are surprised by the creepy guy in the FUBU t-shirt. They mistake him for a homeless man but he screams at Jeff, “Do you want to live forever? DO YOU?!”

Russ goes to town on the guy with a frying pan, breaking his neck. Supernaturally, the guy’s neck straightens back out. Russ goes after him some more with the frying pan, but the old guy is mostly just annoyed, “That. Doesn’t. Work. Asshole.”

Who is this old guy, and why can’t he die?

His name is Angus, and he’s the first character in the script we meet besides Jeff. He’s an eleven-hundred year-old cantankerous immortal, and in the first five pages of the script, we learn that he’s the man who invented the longbow in the 1400s. He’s a Scotsman hanging out in the French countryside when he’s accosted by King Henry V, who steals his longbow, “Lord in Heaven, we will destroy the French with this weapon. Make haste and reproduce this ‘longbow’ for our archers.”

“No, that’s for hunting purposes only. Or possibly killing the Spanish.”

The Britons run him through, leaving him for dead, but that’s pretty much when we learn the guy is invulnerable to death.

In the present day, he’s been stalking Jeff, and we also learn that his life hasn’t been too much different than Jeff’s. While Jeff has been a slacker for a decade, Angus has been a slacker for centuries. In fact, he’s an immortal who waits tables at Applebee’s, and is content to be demeaned by his twenty-something manager, Kaley. Angus is obsessed with not bringing any attention to himself, and as a result he’s a guy who has managed to live through several centuries without ever taking any chances.

Back in Russ’ Great Aunt’s kitchen, Angus humors our heroes as they test his claim of immortality. There’s a time cut and we see that the kitchen is covered in blood, gore and even sinew. “Okay, you’ve poked out my eye, chopped off my leg, stabbed me in the gut, strangled me, held my head under water, burned me –- Gave me something called a suplex, and made me yell the n-word at your neighbor. Are you convinced I’m incapable of dying?”

So Angus is here to tell Jeff that he is immortal, too?

Although there’s a humorous scare that Angus might have the wrong protégé, we do in fact learn that Jeff is immortal. He’s a descendant of the McConnor Clan, a group of Scotsman who were cursed with immortality by a dark wizard from a rival clan. The whole death-proof curse kicks in on their thirtieth birthdays.

Because Jeff is tired of working at a job with a nametag, he decides this new immortality thing is just the shot in the arm he needs. Angus gives him a dire warning, telling him that he must not bring attention to himself. But Jeff blows him off. Burned by Scarlet and his minimum-wage status, his new goal is to get as rich as possible. Russ convinces him, “We gotta think of the most lucrative job for an immortal.”

Well, what is the most lucrative job for an immortal?

They’re kind of unsure, but Russ decides that being a daredevil and landing in the Guinness Book of World Records is a good start. Meanwhile, Jeff begins courting Liz Johnson, his old prom date from high-school. She’s a recent divorcee who has moved back to town to start anew. Apparently, all her ex did was play videogames all day and get hammered with his buddies, and Jeff does his best to hide the fact that he owns an XBOX and a bong.

But, you know, this his chance to change things for himself.

Jeff the Javelin attempts to jump a shark tank on a motorcycle at Big Joe’s RV Emporium, but the news crews gathered for the event capture a horrible accident and the miraculous death and resurrection of Jeff on their cameras.

Uh oh. Lemme guess. His high profile catches some unwanted attention?

You got it.

In Venice, Italy, we meet Gargomel of the McDonald Clan. No, I’m not making this up. The villain’s name is Gargomel. Yes, it’s from The Smurfs. He watches Jeff’s footage, suddenly a man possessed. He tosses the scantily clad Italian whores from his bed and pulls a gigantic sword out of a chest. He tells his Peter Lorre-like assistant, named Pierre, “Get me the next flight to America.”

As Jeff considers his next move, which is either lion tamer or man-on-man porn, Gargomel arrives in town, donned in his Wicked t-shirt and wielding his giant ass-kicking sword. He enters the Bullseye Department store and punches out the elderly greeter. And, that’s when we’re treated to some Highlander-esque mayhem in what is pretty much a Target, with Angus arriving to save Jeff’s ass. It’s pretty gory as whole torsos are dismembered and regenerated, and several civilians are possibly poked with stabby objects.

So, Jeff isn’t one-hundred percent immortal?

Right again.

Turns out that Gargomel is from the rival clan that cursed the McConnor’s. Because of the magic involved with the curse, the McDonald’s gave the McConnor’s eternal life, but they accidentally cursed their own progeny to die at age thirty.

Gargomel is approaching his thirtieth birthday, and the only way for him to reverse his curse is to kill an immortal from the McConnor Clan. He wields the Sword of Braemar, a blade tipped with a rare yellow diamond mined from the Glen Braemar Mountain. “If this stone pierces your heart, you will cease being immortal. You will die.”

Jeff also learns that Gargomel’s parents killed his own parents.

To complicate matters, Liz’s life is also put in jeopardy.

Sounds fun! Does it work?

I thought so. I think this script is a perfect example of how to write a fantasy comedy (or a horror comedy). It’s funny, without losing sight of the story. It’s adventurous, without going off the rails. It’s silly, but it’s smart in how it exploits and parodies the genre. It has a simple mythology, that never once feels convoluted, confusing or complicated.

And it does all this while providing a satisfying emotional journey for the protagonist.

But calling “Jeff the Immortal” just a parody film would be like calling Shaun of the Dead just a parody film. Sure, it pokes fun at the genre, but never at the expense of respect to that genre. It’s a genuine fantasy story with an honest-to-God emotional arc that is about stepping out of your comfort zone, taking chances and claiming your destiny as a hero. It’s kinda like an Apatow flick, but with swords. Hollywood, can this please star Jay Baruchel?

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[x] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Villains are rarely the villain in their own minds. Yep, I’m pretty much quoting Warren Ellis on this one, but there’s a scene in “Jeff the Immortal” that perfectly illustrates this idea. Jeff banters back and forth with Gargomel, “This isn’t over. The hero will triumph.”

“Yeah! I know.”

“You…want me to triumph?”

“You? I’m the hero.”

“No, you’re the villain. I’m the hero.”

“No…I’m the hero.”

“How are you the hero?”

“I die at 30. I’m fighting for my life here. That makes me the hero.”

Gargomel is the hero in his own story. Gargomel doesn’t want to die when he turns thirty. To achieve this goal, he has to kill Jeff. And, Gargomel is pretty much willing to do anything to prevail. So, let me quote Warren Ellis again, “The difference between a ‘hero’ and a ‘villain’ is often the ruthlessness and extremity they’re prepared to go in order to achieve what they want.

Watch Scriptshadow on Sundays for book reviews by contributors Michael Stark and Matt Bird. We try to find books that haven’t been purchased or developed yet that producers might find interesting. It’s been a few Sundays since we’ve had our last one, and that’s mainly my fault, but Stark is back, and he’s doing something a little different – a look at the best characters in crime fiction. Check it out!

Welcome back to another edition of Scriptshadow’s Meaty, Beaty, Big and Bouncy Book Club. While we hardly wield an ounce of Oprah’s mighty literary clout, we do hope a few trolling producers and story editors listen to our glowing endorsements. May there be little rest for their reading department as they write massive tons of coverage over this holiday weekend.

Today, we’re gonna talk about some of our favorite crime fiction characters and wonder aloud (Insert dirigible-sized thought balloon here) why the hell they haven’t been brought to the big screen yet. Now, all but one of ‘em are from best-selling novelists. All have had their rights quickly snapped up. And, mysteriously, all seem to be languishing in some dreaded level of development hell.

But, at Scriptshadow, we don’t fear the reaper. Let’s pay the damned boatman, throw Cerberus off our scent with some strategically placed Omaha steaks and try to free a few of the damned good reads held captive here.

1. Harry Bosch by Michael Connelly

“Everybody counts or nobody counts.” – Harry Bosch

I am indebted to Michael Connelly not only for nearly 20 years of excellent reading pleasure, but for introducing me to the classic, Art Pepper Meets The Rhythm Section, one of his character’s favorite albums and now one of mine. The recording session of that historic slab of wax is pretty damned worthy of a movie in itself — Pepper, a smack-addict, played through all of it with a broken reed and it’s still bloody brilliant — But, as usual, I digress…

Connolly went from cub crime beat reporter to one of America’s most respected novelists with over 23 bestsellers to his name. So far, there’s only been one film adaptation of his work, Clint Eastwood’s Blood Work. We have yet to see his most famous and beloved character, Harry Bosch, hit either the big or small screens.

And, that’s a crying shame!

Hieronymous “Harry” Bosch was named after the 15th Century Dutch painter known for his surreal landscapes of sin, punishment and hellfire. This pretty much mirrors this LA cop’s beat — and life. His mother was a prostitute who got murdered (shades of the Black Dahlia) when he was 11. He bounced around various orphanages and foster families till he finally ran away and joined the army, serving a still-soul-scarring-stint in Vietnam as a sewer rat, navigating the enemy’s deadly mazes of underground tunnels.

Even above ground, and in the light, Bosch still works the same way through LA’s toughest cases, meticulously and stubbornly, with little regard that it all might suddenly blow up in his face.

Bosch’s mission is to speak for the dead. He is a relentless case closer, even if it means defying authority. Following his career and character arc for the past 14 books, we’ve watched him age, find and lose love, become a father, make new enemies and rise through the ranks to Homicide Detective.

He’s even been thrown off the force, working unsolved cases as a P.I.

In The Last Coyote, he’ll solve the 30-year-old murder of his mother, the motivation for his profession and his dogged persistence. He’s worked many of the city’s politically sensitive cases, still hounded by the schmucks from internal Affairs and still getting in the face of his higher ups.

Much of his life is a something of a mess. His romances with both cops and civilians are strained and complicated. Even the house he bought working as a cop show’s technical advisor is condemned after the Northride quake. Confrontational to the end, he ignores the yellow tape and keeps sneaking back inside.

Where to start? From the beginning. His first book, The Black Echo, won Connolly an Edgar award. Follow Bosch through to the most recent, Nine Dragons, where he’s way out of his element, rescuing his daughter from Triad leaders in Hong Kong. To watch the author segue from journalist to novelist, I recommend Crime Beat, a collection of his articles from the Sun Sentinel and The LA Times.

Connelly is case and point that Hollywood purchasing your novel can be a mixed blessing. He is currently suing Paramount, trying to get the rights back to his first three Bosch books. After 15 years of non-action, he should be able to buy his babies back. But, beware of studio accountants and their evil abacuses. His bill got padded by years of “Out of pocket” development costs and pricey producer fees.

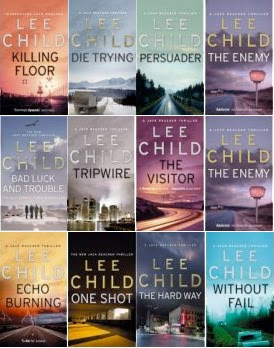

2. Jack Reacher by Lee Child

“Lee Child’s tough but humane Jack Reacher is the coolest continuing series character now on offer.” – Stephen King

Highly prolific, Lee Child has written 14 bestsellers in 13 years. So, why is his vastly popular creation, Jack Reacher, taking so much damned time getting to the silver screen?

We’re talking international best sellers here!!! Published in 51 countries and 36 languages!!! Uh, I thought foreign markets were supposed to be a good thing?!! Where are those studio accountants with the evil abacuses when you actually need them?

Instead, Hollywood fast tracks a comic book which sold a grand total of half a baker’s dozen copies, a board game that no one has played in over thirty years and a 3-D animated feature based on a breakfast cereal no sane parent would ever feed to their kids.

Do we really need Cookie Crunch – The Movie? Probably not. Do we really need a Jack Reacher series? Yeah, you’re darn tooting we do!

Lee Childs a British television director. has created the ultimate, iconic, American action hero. Reacher is James Bond with just a toothbrush and the shirt on his back. He’s Jason Bourne but with memory (of stuff he’d rather forget). He’s Bill Bixby’s Incredible Hulk, a knight-errant, wandering the countryside helping out fair damsels and regular joes who coincidentally just happen to be in distress. Guess Reacher has some serious when-shit-is-gonna-come-down radar going on.

He doesn’t look for bad luck and trouble. It just kinda finds him.

Reacher is a former Army MP Major who grew disenchanted with all the bureaucratic military bullshit and retires to an uncomplicated life of aimless drifting.

Raised as a military brat, the dude comes with some major assets – premium fighting skills, lighting fast reflexes and near bionic powers of observation. He relies every now again on some of the brass he knew back in the day for a little intel.

He also doesn’t come with much baggage. Worrying that actually washing his clothes might lead to needing more possessions like a suitcase or a house, he keeps his life zen-monk simple. The guy travels the country either by bus or by thumb, buys new clothes when the ones on him get too ripe and resorts to manual labor (or ripping off a bad guy’s stash) when his wallet gets empty.

Many of the Reacher books have the same MO. He ambles into a small town, smells trouble, takes care of trouble, leaves a lonely, local beauty quite satisfied and unceremoniously drifts away. Nothing wrong with a little familiarity. It’s a damned good MO.

According to Child’s website, all of the Reacher books have been optioned. Yet, there’s only one currently in any form of pre-production — One Shot, with Josh Oslon (A History of Violence) as the hired scribe.

Note to Paramount. Listen to the fans on this one. Hell, I think if you’d give Josh Holloway a shave and a haircut, you’ll have yourself a nice franchise. With MGM’s James Bond on hold, we need Jack Reacher more than ever.

3. Gabriel Allon by Daniel Silva

“He is the prince of fire and the guardian of Israel. And, perhaps most important, Gabriel is the angel of revenge. “ Daniel Silva on naming his protagonist.

We asked for a thriller. We asked for political intrigue. We asked for an awesome Mossad agent that comes out of the cold.

What we got was You Don’t Mess With The Zohan.

Oy!

There are nine books in this series Silva launched back in 2000. Universal acquired the rights to the entire catalogue in 2007. But, again, there’s only one in any stage of pre-production, The Messenger with Pierre Morel (Taken) tapped to direct.

Daniel Silva was the Middle East correspondent for United Press International – the perfect background for one about to embark on a career of writing spy thrillers.

His creation, Gabriel Allon, comes with much of the same skill sets as Reacher, but with a truckload of more baggage. His cover is also damned fascinating. The spy happens to be one of the world’s most renowned art restorers. Thus, we know the man is patient, deft and has a keen eye for detail. Guess it takes some of the same talents to kill a well-hid terrorist as it does to touch up an aging Caravaggio.

He’s the son of two Holocaust survivors and grew up in the Jezreel Valley of Israel. German was his first language. Languages would be one of his many giftings. The other is art. It’s in his blood — his mother being one the country’s most famous painters. Recruited back in art school, Allon becomes an assassin for the Israeli Secret Service, killing six of the twelve Black September members responsible for the 72 Munich Olympic murders.

But, payback can be a bitch. Exacting a few eyes for an eye, the PLO retaliates years later in Venice, killing Allon’s son and disabling his wife with a car bomb meant for him.

Allon is a spy that would rather stay out in the cold. He is an able killer but conflicted with a conscious and the ghosts of his past. His wife has been confined to a mental hospital all these years. He’s rather concentrate on saving the great works of art decaying in the old, damp cathedrals of Venice. Yet, current events keep bringing him out of retirement. The world keeps needing saving as well.

One of my favorite recurring characters is the spymaster who recruited him, Ari “the Old Man” Shamron, a legendary operative himself who captured Adolf Eichmann back in the day. He basically created Allon and pretty much won’t allow the unhappy spy to ever retire and live in peace.

Allon’s missions have dealt both with both “unfinished” Nazi business (looted art, the Vatican’s involvement and war criminals) and terrorism (the PLO, Saudi Arabia’s role in al-Qaeda and the rise of militant Islam in Europe). These thrillers are timely, taunt, globe trotting and nearly impossible to put down. They’re everything you want for a good summer read and — ahem — a summer blockbuster.

With a new book, The Rembrandt Affair, coming out later this month, Allon will be – luckily for us — laying down his brushes and picking up a Beretta one more time.

4. Angela Gennaro by Dennis Lehane

“Now, would you like to eat first, or would you like a drink before the war?” – John Cleese in Faulty Towers

Okay, technically, the low rent, south Boston PI team of Kenzie and Gennaro have already made it to the big screen in Ben Affleck’s Gone, Baby, Gone. And, although the movie had some awesome, Oscar-worthy performances, Gennaro’s character was pretty much sidelined for almost all of it. And, how did this spunky, Italian fireball become so damned Monaghan cute, quiet and Irish all of a sudden?

Gone, baby, were their sexual tension, their wisecracking, her mobbed up family members and all the psychic damage from her abusive marriage.

I’d love to see these guys a bit truer to the books in an HBO series. Think of it as Southie Moonlighting with the infamous, gritty Lehane edge.

Growing up together on the blue-collar streets of Dorchester, Patrick and Angie have always been friends, sometimes been lovers and seem to work pretty well together in cracking a case. They run their agency out of the belfry of a church where “all manners of unholiness cross their threshold”.

At times, they rely on a little help from their old friend, Bubba Rugowski, an arms-dealing ultra-violent psycho — A dude even Spenser and Hawk wouldn’t tangle with.

Lehane seems to experiment a bit with each of the books in the series. Darkness, Take My Hand is a search for a serial killer. Sacred is a bit of a surreal, screwball updating of Chandler’s The Big Sleep. Gone, Baby, Gone, as you know, gets pretty dark and grim. Not all of their cases end up with Dave and Maddie popping open champagne bottles and speaking in iambic pentameter.

Fans of the six Kenzie-Gennaro novels will be relieved to hear that after an 11 year hiatus, they’ll be back sleuthing this November in Lehane’s latest, Moonlight Mile.

5. Allen Choice by Leonard Chang

“The key is character. Chang works like a painter, carefully brushing strokes of truth and depth on all of his characters.” – Michael Connelly

So, our past four have all sprouted from the Underwoods of best selling authors. Here’s the one character you probably don’t know about, but should. So, buy the books now and thank me later.

Choice is a Korean-American, Kierkegaard-reading executive protection expert, who by the third installment of the series, becomes a full fledged, hard-boiled, private investigator.

Unlike most PIs, he doesn’t crack wise too often. Unlike Spencer (My gumshoe standard), who passes the time during stakeouts making mental lists of his favorite baseball players and ranking the gals he’s seen naked, Choice seems to worry a lot, brood and doubt almost every decision. I like that. I identify with that. It sets him apart from most of crime fiction’s overconfident detectives, making him and thus the stakes that much more real.

He also deftly dispels the stereotypical baggage of the inscrutable Asian sleuths of yore like Charlie Chan and Mr. Moto. Choice doesn’t know any karate and he can’t fix your fucking computer. He also doesn’t speak a word of Korean and knows very little about his heritage, which is a huge stumbling block when meeting his girlfriend’s extremely traditional parents.

At one point he calls himself “an ethnic dunce”.

He’s both assimilated and alienated at the same time. Everything about Choice seems in conflict. Orphaned at a young age, he doesn’t have much of a compass when it comes to family or relationships. He tries to compensate by reading the great philosophers. I think it just mixes him up more. Imagine the soul of 60s stand-up era Woody Allen sucked out and transferred into the body of a former linebacker.

The third book of the series, Fade To Clear, would make a pretty neat, little flick. The plot, in some ways a distant relative to Gone, Baby, Gone, involves a bitter custody battle with the abusive father abducting his daughter. Choice is hired to find the girl. The case is far more complicated than it appears.

First off, the mother is something of a bitch. Her ex-husband is involved with some rather shady shit. The ex-husband’s brother is a professional psychopath. And, the worried mother’s sister happens to be Choice’s old (but not completely burned out) flame.

Treating it like a routine skip tracing case turns out to be a big mistake when we learn that he wasn’t the first PI they’ve hired. Seems the sisters neglected to tell him that his predecessor ended up quite dead.

Like Lehane, these streets (These Streets of San Francisco this time) get dark and gritty and noir to the bone. It’s good work. I hope Chang returns to this character real soon.

Daniel Dae Kim (Lost) has optioned the first two Allen Choice novels. But, like all the books we’ve mentioned here, this project needs a Get Out of Limbo card stat!

So, my case is finally drawing to a close. I’m optimistic though. Warner Brothers has just recently resurrected one of my favorite books, Carter Beats the Devil. Hopefully, other studios will follow suit and go back to their libraries, refocusing on some of the books that they’ve already paid damn good money for.

More of Stark’s naughty kvetchings can be found on his blog — http://www.michaelbstark.blogspot.com

Genre: Drama

Premise: A 17 year old New York girl witnesses a bus crash that kills a woman and battles with the secret that she may have been indirectly responsible.

About: This has got to be one of the craziest stories to ever come out of Hollywood. “Margaret” had a great cast: Matt Damon, Anna Paquin, Mark Ruffalo, Matthew Broderick, Jean Reno, and Olivia Thirlby. They shot and finished the movie all the way back in 2005. But guess what? It’s never been released! Why? Well, it appears that Lonergan (who wrote and directed the film) can’t finish the edit! Apparently, he and the producer can’t agree on a cut of the movie. Numerous other producers have tried to come in and help, but no matter what anybody does, a consensual cut of the film has not emerged. This has, of course, resulted in tons of lawsuits. Making this even more mind-boggling is that Martin Scorsese watched a 2006 cut of the film and dubbed it a masterpiece (it should be noted that Scorsese directed Lonergan’s “Gangs of New York.”) – The Los Angeles Times did a nice lengthy article on the troubled film here. Fascinating stuff.

Writer: Kenneth Lonergan

Details: 185 pages – July 15, 2003 draft (This is an early draft of the script. The situations, characters, and plot may change significantly by the time of the film’s release. This is not a definitive statement about the project, but rather an analysis of this unique draft as it pertains to the craft of screenwriting).

I have never read a script like this one in my life. To give you an idea of what you’re in for, the script is titled “Margaret,” yet there’s nobody named Margaret in the script. It’s also 185 pages long. Back up, read that again. It’s not a misprint. The script is 185 pages long. Here’s the thing though. Numerous people have told me the script is awesome. Someone even went so far as to call it “brilliant.” All of this just adds to the mystique of the project. And Lonergan, for those who don’t know, wrote and directed the great “You Can Count On Me,” one of my favorite indie films of all time. He also wrote the respectable “Analyze This” and “Gangs Of New York.” But this script is in an entirely separate class. It’s an epic tale about…a girl who witnesses a bus crash?? What the hell is going on?

Lisa Cohen is a 17 year old New York girl butting heads with her emerging adolescence. Emotions converge with confusion and create this dark uncertain path which Lisa’s been walking down, blind as a bat. She lives in New York, goes to a private school on scholarship, has a commercial director father who lives in L.A. and a struggling theatre actress mother who lives with her and her brother in their small New York apartment.

In anticipation of a horse-riding vacation she’s been planning with her dad, Lisa goes out to find a cowboy hat. The search yields a big fat donut hole but just as she’s on the verge of giving up, she spots a bus driver wearing a cowboy hat worthy of a John Wayne film. She tries to flag him down but he’s already on the move. Eventually he spots her and engages in flirty back and forth wave. As a result, he misses the red light, and plows into a woman crossing the street, who dies soonafter.

Feeling partly responsible for the accident, Lisa doesn’t reveal the blown red light to the police, which gets the bus driver off the hook. But as time goes by, Lisa begins to feel more and more uncomfortable about what she’s done, and decides to change her statement. She gets in touch with the woman’s best friend, the bus driver himself, and a team of lawyers, and brings a lawsuit against the MTA to try and get the bus driver fired.

But this is not all Margaret is about. Oh no no no. There are tons of secondary storylines going on here. These include her mom dating a semi-creepy foreign guy , Lisa’s crush on her teacher, Lisa’s friend’s crush on her, Lisa losing her virginity (to yet a third character), Lisa’s phone relationship with her father, countless private school classroom debates about racism and terrorism (keep in mind – this was written 2 years after 9/11), Lisa’s friendship with the bus victim’s best friend, a school play, and probably a few others I’m forgetting. In other words, there’s a lot going on in Margaret.

If I’m being honest, I don’t know how you *couldn’t* have problems in the editing room with this script. Let’s call a spade a spade. A story about a girl who witnesses a bus crash and tries to get the driver fired is not worthy of 180 pages of script. It just isn’t.

I mean yeah, all these additional story threads tell us more about Lisa, but there’s so many sides to her, and these sides are so disconnected and random that it’s nearly impossible to grasp what she or the movie is about. For example, we have these long drawn out debates in the classroom about Israel and Palestine, or terrorism and the middle east. Yet what does any of that have to do with a girl who wants the truth to be known about a bus accident? If there was some connection – any connection – between the two worlds, then I could buy it, but there isn’t. For example, if the bus driver were Middle Eastern, there’d be a physical link between the 30 minutes of terrorism debates they have at school and the personal problems she’s having outside of school. But each storyline is so compartmentalized, it feels like it could be its own movie.

Her mom’s relationship with the strange admirer is another example. I couldn’t find any connection between that relationship and Lisa’s situation. The long calls with her father and this phantom horse-riding trip also perplexed me. I honestly believe that had you taken these storylines out of the script, absolutely nothing would be lost. The core of the story here is Lisa’s desire to release the truth. Anything that doesn’t have to do with that isn’t necessary.

There are other things that bothered me too. Lisa acts completely retarded at times. She keeps saying she doesn’t want to get anybody in trouble, yet she’s filling out police reports accusing a man of killing someone. In what dimension does she think nobody gets hurt here? Also, her motivation is constantly changing. One moment, all she cares about is taking down the bus driver, and the next she’s hellbent on losing her virginity. These segues are so jagged I felt like we were cutting between different dimensions.

Strangely, despite all this, I found myself compelled to keep reading. I wanted to find out what happened. I wanted to see the bus driver fall. I wanted to know how all these threads were going to come together. The fact that they didn’t was upsetting, but you can’t discount the fact that you just read a 185 page script in one sitting. From a pure writing standpoint, that’s really hard to do. So I give Lonergan some dap for that.

It’s just…I guess I’m shocked that this script was even made in the first place. These problems they’re rumored to be having in the editing room – well of course they’re having problems. How do you edit a movie where you can make the argument that 9 of the 12 subplots aren’t necessary to making the story work?? Editing a film is about serving the story. You’re supposed to get rid of anything that doesn’t push the story forward. The issue here is that Lonergan had no intention of making the kind of movie that lived by those rules. This is one of those “trust me, I know what I’m doing” deals and it looks like they didn’t trust him.

If this were my story, I’d chop it down to a reasonable 2-3 subplots and allow the bus crash plot to drive the film. Cause do we really need to spend 25 minutes watching a man court Lisa’s mom? Does that add enough to the story to warrant its existence? I’m assuming they’ve already asked these questions a thousand times. So I’ll take my opinion train to the next stop.

A fascinating screenplay but man was it all over the place.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: While long screenplays are risky as hell, they’re okay IF the subject matter warrants the length. A biopic that spans 30 years? I can buy that as a 3 hour movie. A fantasy film with dozens of characters sprawled over a huge geographical landscape. You can make an argument for needing 200 pages to tell that story. You can’t convince me that a movie about a girl seeking justice after a bus accident warrants a 3 hour running time. You just can’t.