Search Results for: F word

Genre: Comedy/Sci-Fi

Premise: A married couple attending a gender reveal party are quickly informed that they must stop the reveal party at all costs… or the world will blow up.

About: This script finished top 10 on the Black List. Jack Waz has been slowly working his way up the ranks. He was a writer’s assistant on Starz’s, Get Shorty. He wrote a small TV movie called, “Love Blooms.” And now he’s made it to the Black List.

Writer: Jack Waz

Details: 99 pages

Is it finally going to happen?

Am I going to genuinely laugh during a comedy screenplay?

It’d be a first.

Why is being funny so hard for people?

I’m hilarious. Just be more like me.

This script’s got a head start, though, cause I love the logline. As I stated in my annual Black List assessment post, I think gender reveal parties are HI-larious in how stupidly insane they are. Especially because of how much it sucks when you find out it isn’t a boy.

Carson, it’s 4 days into the New Year. Let’s not get cancelled!

Meg and Andy, both in their 30s and still acting like they’re in their 20s (getting wasted every night), reluctantly agree to go to Meg’s sister’s (Grace) gender reveal party. Since these two are not into kids, going to a gender reveal party is their own personal nightmare.

Of course, it’s about to become an actual nightmare, because once they get there and everyone settles in, a giant shipping container is opened and blue balloons shoot out into the sky. It’s a boy!

Except Air Force One happens to be flying by at that very second, the balloons get pulled into the engine, the engine explodes, the president dies, and the United States retaliates against Russia and China, who they think shot the president down, and ten minutes later there is no earth.

Luckily, right before Meg and Andy die, some guy named Tank shows up. He’s buff, naked, wears a fanny pack, and is from the future. He tells them he’s time traveled back here to stop this gender reveal party in the hopes of saving the world.

So Tank time travels them back to the morning, tells them they’ve got five shots at stopping the gender reveal party. And off they go. But in their initial attempt, which includes popping all the balloons ahead of time, the sister’s husband has a backup plan! A series of fireworks go off that, when they blow up, reveal the gender. Oh, except it triggers a massive earthquake and the earth splits in two!

The group quickly learn that there are forces bigger than them determined to make sure this reveal happens. They will have to outwit fate to save the planet. But, more importantly, put an end to this evil attention-seeking practice that soon-to-be parents all across the United States participate in – the gender reveal party!

Baby Boom, which definitely needs a title change with the words, “Gender Reveal Party” in it somewhere, is its own unique beast. It’s a quasi-time loop comedy with a spritz of Final Destination thrown in.

The script is written in a brisk effortless style, as every comedy should be. The structure is solid, as it’s divided into five sections, each with a big goal (prevent the world from blowing up).

But for me, it’s more of a “smile” comedy than an “lol” comedy. To be fair, most comedy scripts I read get nowhere close to “smile” level. They live closer to “neutral” and “scowl” level. So I don’t want it to sound like I’m dissing Baby Boom for only making me smile. That’s actually a compliment.

Here’s the thing I’ve learned about comedy.

It’s mostly about performance. It’s about the actor adding their own flourish to the action, to the line, to the performance. When you think about the funniest moments you’ve watched (imagine Step Brothers for example), virtually none of them work without that particular actor delivering that particular line or that particular action in that moment in that particular way.

So it’s hard to judge comedy on the page.

With that said, it goes to show that if you *can* manage to make a script funny on the page, you have something incredibly special. So I’m always looking for that. Even if it is a unicorn.

One thing that can really ramp up your comedy is stakes. The reason for this is that when stakes are higher, it creates tension. We feel that tension since more is on the line. This creates a tightening of your body and primes it for release, which of course comes in the form of laughter. When you don’t have that tightening, there’s no need for release.

Baby Boom low-key doesn’t have any stakes.

On the surface, it looks like it does. The world is at stake!

But they tell us, right from the beginning, that we’re going to get five shots at this. So we know we’re good for the next 75 minutes. They’re going to make it out of each world-ending catastrophe just fine.

Baby Boom has stakes in its fifth and final attempt. But you’ve asked us to endure four meaningless sections to get to the actual danger.

Just so you know, this is not a hard and fast rule. There are examples of screenplays that work with low stakes. To do this, though, you have to excel in other areas of your script, usually the character front. But I just wasn’t into the characters here. I mean, I thought they were fine. Meg and Andy did a solid job taking us through this journey.

But my ultimate character litmus test is, “Would they be interesting without this particular plot surrounding them?” Are Meg and Andy interesting as everyday people? If we were to follow them around for a day, would we be infatuated with them? Not really. There’s some late script stuff where they battle whether they’re ready to have their own child that’s pretty good. But as people, I only ever smiled at a few things they said or did.

Tank was clearly constructed to be the breakout character here but he was just too wacky for me. A naked guy from the future wearing only a fanny pack is a funny image but it felt like it belonged in a South Park episode, not this movie.

Despite all this, I thought the Final Destination angle was a stroke of genius. Waz seemed to anticipate a problem with all the repetition that came with the five similar sequences. So he made sure to keep us guessing on how the world was going to go belly up each time. My favorite was the AI takeover. I thought that was clever. And the Air Force One accident was fun as well.

As confident as I feel in my assessment, I’m aware that I haven’t laughed at a comedy script in forever so the problem could very well be me. Also, this script reminded me A LOT of the script Michael Waldron wrote to get on the Black List, The Worst Guy in the World and the Girl Who Came To Kill Him. And we all know how things turned out for him.

Anyway, did anybody read this? What did you think?

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: It used to be that you could sell a comedy script pretty quickly by following the simple rule of capitalizing on a popular cultural trend. Remember when “Bromance” was a thing? There were like five comedy specs about bromances that sold. When Uber came out, we got a couple of ride-share comedies, with, “Stuber” getting produced. Wedding Crashers is another example. Baby Boom’s high placement on the Black List proves there’s still interest in this approach. So if you’re looking for a comedy idea, this is a good well to draw from. Maybe we can all brainstorm in the comments section current popular culture terms that would make good movies. Getting cancelled is probably a good starting point.

Genre: Drama/Thriller

Premise: A young woman obsessed with eating healthy becomes convinced that all the food she puts in her body is rotting, leading to her having a meltdown at her sister’s wedding.

About: This script finished NUMBER 1 on the recently released 2022 Black List.

Writer: Catherine Schetina

Details: 94 pages

One of the more popular topics for a Black List script is the main character having an unhealthy obsession with something. A ton of these scripts make the Black List so it’s a topic worth considering if your goal is to make the list. In the past we’ve seen obsession over exercise, bodybuilding, porn, influencers.

It’s the car crash principle. We know the crash is coming. And we can’t help but keep looking. We want to see what happens when our hero’s crash finally comes.

30 year old Hannah Abrams works a retail job and bemoans the fact that she doesn’t have her life together. She’s in a relationship with her girlfriend, Cal, who’s a local school teacher.

The two have a great relationship except for one problem. Hannah has orthorexia, a condition where healthy eating becomes an obsession.

Hannah isn’t thrilled that she has to head up to Northern California to her perfect lawyer sister’s wedding but Cal going with her makes it a little easier. On the way up, the two stop to get food and Hannah buys a salad. She then flips out when one of the pieces of lettuce has mold on it.

Hannah tells Cal that the only way to deal with this poison going inside her body is to go on a cleanse. “During your sister’s wedding?” Cal asks. Yup, Hannah says. You see, to Hannah, all her little weird food solutions make total sense, even if no one else understands them.

Once at the weekend cabin, Hannah struggles mightily to survive during group meals. Everyone slurps up chemically-injected food sources. To Hannah’s horror, even her own girlfriend chows down on steroid-injected beef like it’s no big deal.

On that first day, Hannah is horrified to find that there are maggot eggs underneath her fingernails, no doubt from that rotten salad! So she tears away at her fingernails. But she doesn’t get rid of it all because, the next day, she finds maggots on her hands. And also underneath her skin!

Hannah goes into major damage control, scratching and clawing into her skin to capture the little buggers and pluck them out. She also stops eating, causing her to look more and more like a walking corpse. Things get so bad that clumps of her hair keep falling out.

Hannah repeatedly refuses Cal’s help and Cal begins to go through her own mental anguish as she comes to terms with the fact that she’s been enabling this behavior for their entire relationship. It’ll be up to Cal to step to the plate and get Hannah to the hospital before it’s too late. But that’s the problem. IT IS TOO LATE.

I like creepy obsession stories. If you look back through all my reviews of them, I usually give them high marks. I think it’s because we all feel like we’re close to being one of these people. We all have our unique obsessions. What would it take for them to become a legit medical condition? The line between the two is probably a lot smaller than we know.

But the fact that we aren’t yet as wacko as these jokers allows to watch them spiral out of control from a place of comfy schadenfreude. I think that’s another reason these concepts work. We can read them and think, “Well at least I’m not THAT level of crazy!”

I also personally know people who are obsessed with the super-clean food industry and they’re their own level of wacky. For instance, I knew a guy once who bought off-brand milk from Australia because Australia doesn’t pasteurize their milk, or something, and so the milk is the only legit chemical-free milk in the world (his words, not mine). It cost him, I believe, 30 bucks a gallon.

It seems to be this hole you go down that never ends. Cause first it’s Whole Foods since they’re organic. But then you find out that they’re only “certified” organic, which still allows for some light chemicals to be used. So now you start going to Erewhon, which has the truly truly truly organic food. Of course, all the food there cost five times as much. And that’s another element to this obsession. You’re soon paying 100 bucks a day for your habit.

As for the actual story, I give it mixed marks. The stuff that Hannah goes through – first the eggs in her fingernails, and then the maggots, and then the fly eggs, and then the flies coming out of her. I’ve seen that before. I read quite a few scripts where insects are crawling around underneath the character’s skin and they’re trying to scratch them out.

So nothing there really surprised me.

But I did think it was clever to build this narrative around a wedding. A lot of times with these weird indie scripts, the writer focuses so much on the bizarre stuff (like insects breeding inside you) that they overlook a solid defined narrative.

By constructing a script that happens over a single weekend, you take care of that issue. We now have form to our story. We know where the high-pressure points are (Hannah has to give a maid of honor speech). And, most importantly, we know where it’s going to end. It’s going to end in two days. Which means we know we’re not going to be lingering on endlessly.

It’s sort of like Meet the Parents, the I’mFlippingTheFu*kOut edition.

I also liked the relationship aspect of the story. We’ve seen scripts such as Magazine Dreams and movies like Joker that tackle these weirdo characters dealing with their obsessions in isolation. It becomes a different story when the protagonist is in a relationship. Because everything they do affects the other person. And you also have this other character who has to decide – do they stand up to their significant other’s delusions? Or do they nod their head when their partner says, ‘I’m fine,’ even when it’s clear they’re not?

Finally, this script made me think. There’s this moment where Hannah is listening to the radio and there’s a segment about how much micro-plastics we ingest every time we drink bottled water and we have no idea what the long term effects of these micro-plastics are. I drink a lot of bottled water. And now I’m thinking, “Maybe I shouldn’t do that.”

Which I think is healthy. But if I start advocating to rip my skin off to take out the maggots crawling underneath my skin, you have permission to tell me I’ve gone too far.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: “Hannah smiles at her brother. Genuine love there.” You should never ever have to write the second sentence of this line. If you can convincingly SHOW that Hannah and her brother love each other through the actions they take or the words they say, why would you need to directly tell the writer that there’s “genuine love there?” Shouldn’t we already know? In the past, I’ve told writers this is okay, but I realize now that you’re just allowing the writer to be lazy. Do the hard work. Find a couple of moments that unequivocally show that there’s genuine love between Hannah and her brother. And then you never have to tell us in the action description.

Is today a holiday?

Somebody told me today was a holiday. That because New Year’s Day landed on a Sunday, they didn’t feel it was right that we should waste a holiday on a day we already had off, so they added an additional day off and called it New Years Day Adjacent.

Man, I thought screenwriters were the worst procrastinators. Apparently our government is angling to steal our title. They don’t even want to start the year!

I’m curious what the new year is going to bring on the movie front. On the one hand you have the, “movies are dead, TV is king” crowd. And that’s a hard crowd to argue against. TV is pretty freaking amazing at the moment. You still don’t get the level of production value you do on a movie. But it’s close!

Then you have the, “Do you not see what Avatar is doing at the box office” crowd. And they’re pretty convincing too. Because you will never ever get the full experience of Avatar 2 at home. It’s so much better seeing it in the theater. And, apparently, a lot of people agree.

But once Avatar 2’s run is over, we’re in for some dark days, folks. They’re calling 2023’s movie line-up one of the worst in history. I don’t know if that’s true. But the very fact that some people think it’s true is scary.

With that said, I don’t want to get bogged down in theatrical prognostications. Instead, I want to highlight five interesting movie releases in 2023 and talk about the screenwriting obstacles they present.

As I’ve said many times before, every screenplay has its own unique challenges. One of the major jobs of a screenwriter is identifying these challenges and coming up with a game plan for how to tackle them. So let’s jump into it!

Cocaine Bear – Feb 24

Cocaine Bear has a classic screenwriting conundrum. It’s got a “poster-only” premise. What that means is that Cocaine Bear looks great on a poster. It looks great in a trailer. But because the story’s success is so dependent on its wacky titular character, what happens 10 minutes after the bear has been introduced and the shock factor has worn off?

I see this happen all the time in screenwriting. The solution is to come up with a plot that assumes the concept is weaker than it is. In other words, don’t mail in your execution. This is exactly what happened with Snakes on a Plane. It thought its concept was so great that they didn’t have to bother with good characters or a good plot. Never assume that the concept is going to do the work for you. You have to roll up your sleeves and give the reader a great story that could survive whether there’s a cocaine bear in your screenplay or not.

Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny – June 30

(Spoilers) Rumor has it that this is going to be a time travel Indiana Jones movie. Anyone who has tried to write a time travel movie will tell you the same thing. It’s one of the hardest narratives you’ll ever have to write, cause you’re always dealing with a paradox. If the plan doesn’t work, you simply go back in time and try again.

Sure, you can come up with rules like, “You can only time travel two (or three) times,” but therein lies why the genre is so difficult. Cause the second you start adding hard rules, those rules need to make sense within the mythology. They can’t just be rules that the screenwriter needed to be there. That’s when movies start feeling fake.

So, with time travel, you have to outline like an insane person and rewrite like crazy. There’s no other way around it. A well-executed time-travel script will take you twice as long as any other genre script in order to work out all the kinks and make the time travel stuff as seamless as possible. If you’re willing to make that commitment, go for it!

Oppenheimer – July 21

When it comes to biopics, there are two versions you want to avoid. You want to avoid the cradle-to-grave biopic. It’s like the real life version of an origin story — predictable and bland. But you also want to avoid the two-years-in-the-life-of biopic. This is exactly what it sounds like. You’re covering two years of the main character’s life. The reason why both of these are bad is because movies don’t do well with extended timelines. They do well with short contained timelines. Most of the movies you’ve loved have taken place in under two weeks. Why? Because movies go hand in hand with urgency. When we feel like every minute spent onscreen is important, due to time running out, everything about the story feels charged. And if you’re going to write a movie about the biggest bomb in history, it only makes sense that you create a ticking time bomb element to it. If Nolan keeps this timeline tight, the movie has a chance at being good. If we do a slow-burn two-year lead-up to the bomb, I promise you the movie will fail. You can’t make slow-burn studio movies in 2023. You just can’t. And Nolan understands this. Dunkirk takes place in under two hours, right? Then again, Interstellar takes a year so who knows what Nolan will do.

Barbie – July 21

Barbie is, by far, the most challenging screenwriting assignment of the year. And it’s relevant because when you make it as a screenwriter, you will be given impossible assignments like this. And it’ll be your job to come up with an angle that’s compelling. The most notorious example of this is Charlie Kaufman’s, “Adaptation.” The book (about flowers) Kaufman was paid to adapt was so mundane, so boring, so without narrative, that he went crazy while adapting it, to the point of inserting himself into the narrative. I don’t see Greta Gerwig inserting herself into Barbie. But she’s going to have to come up with a really clever way to adapt this because not only is adapting a toy hard, but she’s adapting a toy that is thought of as a prime symbol of the patriarchy. Which means she’s going to have to change the character into something acceptable for modern-day audiences. And it never works when you change something that was super popular for being something else. Normally, that would be my screenwriting advice: Stay true to the character. There’s a reason the world fell in love with Barbie. Highlight that in your adaptation. But you can’t do that with Barbie. It would cause a Twitter meltdown. This is the one property that I have no solution for. If they hired me, I would not know how to turn this into a good movie. Which makes me all the more curious what they come up with.

Mission Impossible: Dead Reckoning Part 1 – July 14

If you are writing a big action movie, it is imperative that you have at least three set pieces that nobody’s ever seen before. Which is why I actually nudge people away from writing movies like Mission Impossible. Because Mission Impossible exists in the real world and, therefore, is going up against 100 years of action movies that have also existed in the real world. Finding three brand new set pieces in a 100 year old genre is its own mission impossible. Which is why I advocate for unique high budget concepts that grant you access to set pieces that haven’t been done before.

For example, if you make an action movie about dream heists, you’re providing yourself with a unique world that contains all sorts of new set piece possibilities. Mission Impossible has found the weirdest way around this issue, which is to promote Tom Cruise doing his own stunts. This way, even though we’ve seen the set piece before, we’re watching it with the knowledge that Tom Cruise really did the stunt, which heightens the experience. If you don’t have the greatest movie star in history to do his own stunts, though, you need to put off writing a traditional action film UNTIL you have three set pieces that have never been seen before. Because, I promise you, if your best set piece is something the reader saw last year at the movies, they’ll forget your script the second they finish it. Another thing to remember is that one hands-down amazing set piece can be enough to get a producer to want to make your movie. Even more incentive to take your time and come up with great original set pieces!

Keeping with the theme of lists this week, I’m going to share with you my ten favorite scripts of the year. These are scripts that I read this year and not, necessarily, scripts that were written this year.

One of the defining tools for me to be able to identify a good script is, do I remember it three months later. Just like movies, sometimes you can see something and enjoy it in the moment, yet that movie quickly evaporates from your brain. You can’t even remember a scene from it two months later.

So as I was going back through all my reviews this year, I was surprised at a few of the high grades I gave scripts because I could barely remember them now. Meanwhile, all the scripts here have moments or characters that are tattooed on my brain. They’ve stayed with me.

I tried to find a consistent theme to all the picks, but unfortunately, they can’t be distilled down into one unifying lesson. The scripts do, however, hit key categories that tend to do well with me, and with professional readers in general.

Those are…

A really likable main character.

A really interesting/weird main character.

A really fun concept that stands out from the pack.

A well-plotted story that moves along at a brisk pace.

Are you ready? As always, if you’re interested in reading these scripts, go ahead and ask in the comments. Someone usually has them. If you still can’t find them, you can e-mail me at carsonreeves1@gmail.com

Let’s do it!

NUMBER 10

Hotel Hotel Hotel Hotel by Michael Shanks

A man wakes up trapped in a mysterious hotel room. All alone in a mind-bending prison, his only chance for escape is through teamwork… with himself.

Thoughts: I read so many scripts that are clearly desperate directors trying to come up with the cheapest best idea possible that entails one room and one actor. Most of these scripts can barely get past page 10 and still be interesting. But Hotel Hotel Hotel Hotel manages to keep throwing weird plot developments at you that keep the story fresh and fun. It’s one of the more inventive scripts I’ve read.

NUMBER 9

Classified by Andrew Deutschman and Jason Pagan

A mysterious terrorist takes over a top secret U.S. mountain military base that contains within it every ancient artifact that the U.S. has ever collected.

Thoughts: One of the flashier projects that was purchased this year. This script represents the pure unadulterated fun that is going to the movies. It evokes the kinds of feelings you got when you went to see Jurassic Park for the first time. It’s got some of that high concept old movie swagger to it. It’s sort of an imperfect script in a way. But it’s so darn fun, you overlook its weaknesses.

NUMBER 8

Van Helsing by Jon Spaihts & Eric Heisserer (newsletter review)

Famed vampire hunter, Van Helsing, is searching for his white whale, Dracula, but is thrown for a loop when he realizes he has a much bigger foe.

Thoughts: This screenwriting super-team wrote a script that’s even more fun than Classified! I always say that it’s the key creative choices you make in a story that decide its fate. And Van Helsing makes a key creative choice to go away from what would be the most obvious direction of the film, and in the process, creates something much better. This should’ve been the movie Universal used to begin their Monsterverse.

NUMBER 7

Challengers by Justin Kuritzkes

Two former best friends, at opposite ends of their sport’s success spectrum, take each other on in a match for the ages in front of the woman they both love.

Thoughts: Luca Guadagnino has hit a speed bump with his latest film (Bones and All). So the decision to follow that up with a tennis movie, the sports genre that has yet to produce a classic film, isn’t looking so great. But Challengers is definitely the most unexpected script on this list. It’s hard to categorize because it seems to drift in and out of sub-genres. Sometimes it’s a tennis film, sometimes it’s a drama, sometimes it’s a sexually erotic flick. But it’s that weird combination of elements that make it such a memorable read. Can’t wait to see how this film comes out.

NUMBER 6

The Bee Keeper by Kurt Wimmer

When his elderly neighbor is duped out of her entire life savings by online scammers and subsequently commits suicide, a bee keeper goes on a rampage to take the scammers down.

Thoughts: Is there a sale that had more buzz in 2022 than this one? Come on, I had to do it. What I love about Kurt Wimmer is he writes these premises that are right on the border of being ridiculous, but because his craft is so tight, he can walk right up to that line and never fall over it. We’ve got an entire agent showdown scene in this script where the agents use bee puns. And yet it works. It’s crazy. Maybe the most fun script I read all year.

NUMBER 5

Drive Away Dykes by Ethan & Tricia Coen

Two lesbians, one slutty, the other conservative, head down to Florida on a road trip, unknowingly carrying a high profile suitcase that belongs to some very bad people.

Thoughts: Never EVER count out a Coen Brother. This is the rare script that follows the cheap Hollywood formula of combining an over-the-top character and a super-reserved character, but leans into the authenticity of each, allowing their relationship to feel genuine as opposed to ridiculous. Also, this script has the best dialogue in the top 10. Not surprising when you have a Coen Brother manning the typewriter.

NUMBER 4

Horsegirl by Lauren Meyering

A unique young woman enters a hobbyhorse dance competition that she’s way too old for while dealing with her mother’s cancer struggle.

Thoughts: Weirdest character in the top 10 by a country mile. I know some of you didn’t like the main character. But here’s my rebuttal to you. You REMEMBER this main character. And you will continue to remember her for many months to come. Do I have to remind you how difficult it is to create even one memorable character in screenwriting? Newbies can write six scripts averaging 20 characters a script and not write a single memorable character. So when someone figures out a way to create an impossible to forget character, that’s worth something in screenwriting. And, also, I just thought this was a tragic story. It really stays with you emotionally.

NUMBER 3

Mercury by Stefan Jaworski

A ride-share driver who’s just purchased his dream car, a 1969 Ford Mercury Cyclone, goes on the Tinder date from hell.

Thoughts: Best plotted screenplay of the bunch. If you want to know how to keep a screenplay moving from page 1 to page 100, read this script right now. Pay attention to everything Jaworski does because he knows how to make you turn the page. And it’s not just in-script decisions. He purposefully came up with this idea because he knew it would allow him to create a fast-moving plot. He planned ahead. Too many writers pick slow ideas and try to create urgency around them. It doesn’t work. If you want your script to move, you gotta pick concepts like Mercury.

NUMBER 2

Air Jordan by Alex Convery (newsletter review)

In 1984, an out-of-shape bulldog of a sports executive at a small shoe company called Nike attempts to sign the hottest basketball player out of college, Michael Jordan.

Thoughts: It’s Hustle meets Jerry Maguire. Which is a great pitch. It’s also a great script to study to see how to write a fast read. But, unlike Mercury, there are no action sequences here. It’s just a guy trying to get a deal done. But the choices the writer makes – such as making the action description super lean so all the pages read fast – and being so dialogue focused, which also helps the script read fast. This is another writer who understands the burden a reader goes through and does everything within his power to make the script as accessible as possible to anyone who opens it. Plus it’s just a really great underdog story.

NUMBER 1

Galahad by Ryan J. Condal (newsletter review)

One of the Knights of the Rounds table, Galahad, must fight for his life when he is erroneously accused of assassinating the king.

Thoughts: Relentless. Brutal. Intense. Not afraid to offend. Not afraid to take chances. This script literally does everything that every writer is terrified to do today. So it’s not surprising that it was written and sold back in 2008. But this script was a revelation to me in that Condal wrote it before our society turned into a big giant p-word. And you can see how fearlessness – which is something all screenwriters used to have and should have – creates much better material. We need to go back to this fearless place if we’re going to start writing good scripts again. Cause everybody’s writing afraid now and art doesn’t work when you’re afraid. It only works when you’re bold. Even beyond that, though, it’s a killer concept with some killer execution. This is what a spec script should look like.

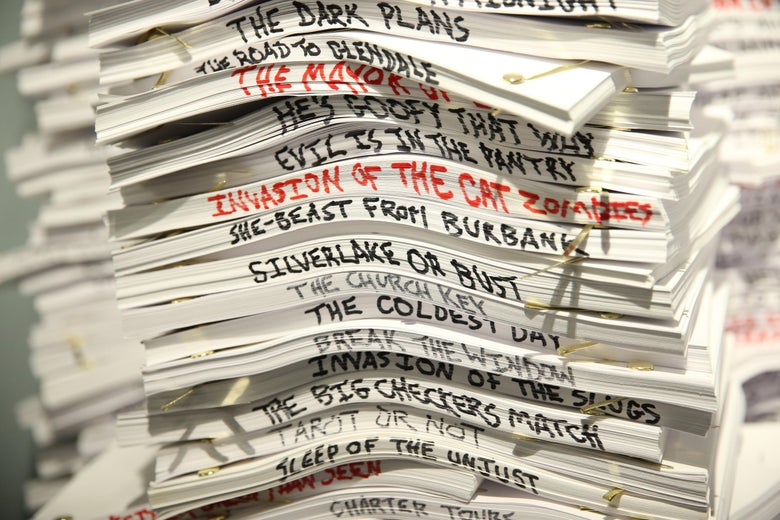

Darnit, I was going to release the newsletter today and have that be it. But now the Black List has come out and you know the game here at Scriptshadow. Once the Black List is out, I have to go over each and every one of the loglines! I have to make grand pronouncements, ignorant quips, praise certain concepts, shake my head at others. It’s a thing here at the site. Looks like I’ll have to release the newsletter tomorrow.

Okay, let’s get into it!

25 votes

Pure by Catherine Schetina

Obsessed with food purity, Hannah’s trip to her sister’s destination wedding descends into madness when she contracts a mysterious foodborne illness that threatens to destroy her from within.

Thoughts: Points for a unique conflict at the center of the story. I’ve never heard of an idea built around a foodborne illness. I’m a little frustrated as to the vagueness. It seems like this could be a horror script? That she turns into a zombie or something. Need more info!

22 votes

Court 17 by Elad Ziv

An over-the-hill tennis pro, trying to salvage her career, finds herself stuck playing the first round of the US Open over and over again against one of the top players in the world. The only way to stop the loop is to win the match, a seemingly impossible task due to how overmatched she is.

Thoughts: This one I have some history with as I helped Elad develop the original version of the screenplay. I’m still in love with the idea of a tennis player who gets trapped in a living hell of having to play the same unbeatable player over and over again. But it looks like the script has changed significantly since I left it as the main character is now a woman as opposed to a man. I was resistant to this choice when we were working on it (it was discussed) because I felt like ego needed to be a big part of the main character. And ego is more of a male thing. But maybe it was the female lead decision that put it over the top with voters. Who knows? Thanks to everyone here who read this script and gave notes on it. I know it helped me see the script’s weaknesses better at the time and I know it was helpful to Elad as well. You are welcome to discuss it in the comments. Do not feel like you need to be nice. There is no preferential treatment here! I still think it could be the greatest tennis movie ever made but, as Elad and I discussed at the time, the bar for that honor is pretty low, lol.

22 votes

Pumping Black by Haley Bartels

A desperate cyclist and his charismatic new team doctor concoct a dangerous training program in order to win the Tour de France. But as the race progresses and jealous teammates, suspicious authorities, and the racer’s own paranoia close in, they must take increasingly dark measures to protect both his secret and his lead.

Thoughts: Look at this. Two sports scripts in the top 3! Is this a new trend? The logline reads like a true story chronicling Lance Armstrong’s plight. But I would much rather this be a fictional movie as you have so much more leniency to make it cool. I like the hint of “increasingly dark measures.” Now you’re talking my language.

21 votes

Pizza Girl by Jean Kyoung Frazier

An 18-year-old pregnant pizza delivery girl falls into an obsession with a stay-at-home mother who is new to the neighborhood.

Thoughts: A modern day Juno? I like the oddness of this logline. There’s something ironic about an 18 year old pregnant delivery girl. It’s not exactly who you expect to be delivering your pizza. And I love weird stalker movies. This could be good.

20 votes

Beachwood by Briggs Watkins & Wes Watkins

Shunned by elite society as a member of the gig economy, a sociopathic dog walker infiltrates an exclusive L.A. community with designs of reaching the top of the neighborhood’s social ladder.

Thoughts: Okay, this is a good logline. It’s built around an underdog. And what do we always say here at Scriptshadow? Everybody likes underdogs. Plus it looks like a fun ride – seeing if this person can start as a dog walker and end up being some sort of rich tech titan.

19 votes

A Guy Goes To Therapy by Shane Mack

When an emotionally stunted townie with no direction is left by his longtime girlfriend, he has no choice but to turn to an option he would have never considered: Therapy. As a result, his entire existence is thrown into flux and his life gets a whole lot worse before it can get better.

Thoughts: This one might be okay. There’s a little bit of irony in the concept. Townies aren’t “therapy” types. That tends to be reserved for the upper middle class and above. Liberal elites with rich people problems. So I like that contrast there. Are the stakes high enough here? That would be my question.

19 votes

Madden by Cambron Clark

After being forced into retirement by the Oakland Raiders, fiery former NFL head coach John Madden teams up with a mild-mannered Harvard programmer to rewrite his fading legacy by building the world’s first football video game. Based on a true story.

Thoughts: Wow! Three sports scripts in the top seven! The return of the sports movie!? Credit Adam Sandler and Hustle, I suppose, for opening the town’s mind up to sports film. I know everybody who loves sports and video games holds Madden Football up as the GOAT. I’m just not feeling this one. The creation of a video game? Not to be rude but who cares?

18 votes

Dying for You by Travis Braun

A low-level worker on a spaceship run by a dark god must steal the most powerful weapon in the universe to save his workplace crush.

Thoughts: You had me at spaceship! Our first sci-fi script of the list. I’m down with that. Looks like we’re looking at a sci-fi comedy, though. I’m not as excited about that. Just because comedy is so freaking hard and I can’t remember the last script I read that made me laugh out loud. But I’m willing to give this one a shot. Cause of the spaceship, of course.

18 votes

Sang Froid by Michael Basha

After a botched delivery of fresh blood, a world weary vampire and a pregnant nurse team up to rob a hospital of their supply.

Thoughts: The real question here is… is this as good as Vampire in Silicon Valley? This is a classic example of why the Black List needs to add genres. Cause I don’t know if this is a comedy, action, dark comedy, or drama script. I guess “world weary” implies comedy. But I still need more information to judge this one.

Context: Vampire in Silicon Valley is a logline ChatGLC came up with when I asked it to for a comedy about vampires. Here’s the logline it gave me – In the high-tech world of Silicon Valley, a young and successful entrepreneur discovers that he is a vampire. As he struggles to maintain his humanity while navigating the cutthroat world of tech startups, he must keep his true identity hidden while dealing with the challenges of being a vampire in the modern age. With the help of his quirky and eccentric team, he must find a way to use his vampire powers to succeed in the competitive world of tech while also staying true to himself.

17 votes

Baby Boom by Jack Waz

When her sister’s gender reveal party triggers the apocalypse, a woman and her husband have to prove to themselves, and the world, that they’re responsible enough to save it.

Thoughts: This one made me giggle. I love the online backlash against gender reveal parties. I think it’s hilarious. If you’ve never seen the viral video of the dad who finds out he’s having a girl instead of a boy during their gender party and he has a fit, you gotta watch it. It’s hilarious. And I love that someone has taken that premise to the extreme and made one of these trigger the apocalypse. This could be really fun.

17 votes

Jambusters by Filipe Coutinho

A mystery about what paper jams can teach us about life. After an inexperienced detective starts investigating a death at the Paper Jam department of a major corporation on the verge of its centennial, she unwittingly embarks on a life-altering spiritual journey that unearths her small town’s dark secrets.

Thoughts: Now this concept I can dig. This reminds of the Black List of old. A weird idea. But still intriguing. A paper jam mystery? I am so in on this one!

17 votes

White Mountains by Becky Leigh & Mario Kyprianou

After an interracial couple in the 1960s has a horrifying encounter with a UFO, they set out to discover if it actually happened, or if it is just a case of folie à deux–madness for two. Based on the true story of Barney and Betty Hill.

Thoughts: You know that if it has to do with UFOs, I’m there. I’m actually really surprised at the list so far. A lot of these ideas are right up my alley. I’m not thrilled that it’s a true story UFO flick. But Betty and Barney Hill is one of the more interesting stories in UFO lore. There were a lot of layers to this one, starting with the fact that they were an interracial couple back at a time when it was really hard to be an interracial couple and, therefore, bringing attention to themselves was a dangerous move and yet they risked it because they believed they saw something extraterrestrial and that the world needed to know about it.

16 votes

Goat by Zack Akers & Skip Bonkie

A promising first-round draft pick is invited to train at the private compound of the team’s legendary but aging quarterback. Over one week, the rising star witnesses the horrific lengths his hero will go to to stay at the top of his game.

Thoughts: What is going on right now!?? Another sports script!? Definitely a trend at this point. I like this concept because it shows you that moving away from the expected setup is usually the better thing to do. Normally, this movie would play out on the team during a season. But it becomes a lot more intimate when it’s just two people all by themselves. It’s almost like the sports version of Ex Machina. Another promising entry!

16 votes

Resurfaced by Alyssa Ross

After Michael Phelps cements his status as the greatest Olympian of all time, he struggles to build a life and identity for himself outside the pool.

Thoughts: Okay, now things are just getting eerie. More sports! Another smart angle from a writer. If you show Michael Phelps winning a bunch of medals, it’s going to be boring. The more interesting story is, what is your life like when your entire childhood and young adulthood was built around a sport, you conquered that sport, and then retired at age 30. What do you do in life after that? I think that’s an interesting question.

15 votes

Oh The Humanity by Gillian Weeks

A dark comedy about the Hindenburg Disaster; or, the mostly true story about one of the biggest f–kups in history, the assholes who tried to cover it up, and the female gossip reporter who made some Nazis very angry.

Thoughts: You gotta love when a logline starts with, “A dark comedy about the Hindenburg Disaster.” We do have some unnecessary capitalization here in this logline. But I’m going to pin that on some assistant to the manager, not the writer. First time I’ve seen the f-word in a Black List logline. The Hindenburg will always be must-see TV so I’m curious about this one.

15 votes

There You Are by Brooke Baker

When a non-confrontational playwright loses her engagement ring, she must travel through Italy to get it back with a man who was supposed to be just a one-night stand, discussing love and lying along the way.

Thoughts: Hmmm… I have mixed thoughts on this one. I like the irony of someone who’s about to get married having to look for her ring with the man she just slept with. Although, unless the writer uses some high-tech writing wizardry, I suspect that this protagonist will be very hard to root for.

15 votes

Viva Mexico by Miguel Flatow

When a washed-up superhero gets betrayed by a Mexican government, he must lead a populist social movement to fight the Narcos, topple the government, and free the people.

Thoughts: Can’t say this is my favorite logline of the bunch. More bluntly, it’s my least favorite. I guess taking down the Narcos is good. But since this logline lacks specificity, it just feels like a generic movie in my head.

14 votes

Colors of Authority by Kevin Sheridan

Escaping his father’s shadow, James Sexton, the son of a Sheriff in Alabama joins the Los Angeles Sheriff’s Department with lofty ambitions of one day becoming Sheriff himself. But these dreams quickly sour when he realizes that the department he serves is mired in corruption and a systemic culture of moral depravity. At war with powerful figureheads within the department, threats of death looming from all sides, James betrays the department’s code of silence in order to incriminate his father’s close friend, Sheriff Lee Baca. This is based on a true story.

Thoughts: We officially have the longest logline of the list so far. This is also the most serious sounding script. And it looks like the most ambitious script. There are a lot of things that it looks like the writer is trying to do in this story. Hopefully he can pull it off but I probably won’t read this one unless someone I know tells me it’s great.

14 votes

The Midnight Pool by Jonathan Easley

Burdened by the loss of his wife to a suicide cult, an embittered investigative journalist infiltrates an elite secret society, only to find something far more sinister.

Thoughts: I like elite secret societies. But not so much something “far more sinister.” I’m not a fan of those vague logline endings. There are a lot of scripts like this out there. So I’m going to reserve judgement until I read the script. Hopefully there’s a unique voice or a unique angle to the story that differentiates it from all the imitators.

14 votes

They Came From a Broken World by Vanessa Block

The year is 1955. The small town of Boon Falls has provided a local forest as refuge to aliens fleeing their war-torn planet. When Mia–young woman dealing with the trauma of her mother’s death–stumbles upon an Alien woman who needs her help, a series of haunting revelations in the refugee forest leads her to an unimaginable truth.

Thoughts: I love aliens. This feels, however, like one of those wishy-washy not-really-about-aliens type scripts that’s more about the metaphor than a riveting story. Not saying that dooms the script. But it’s much harder to makes those scripts pop. I’ll read anything with aliens in it, though.

13 votes

Dumb Blonde by Todd Bartels & Lou Howe

The origin story of Dolly Parton, following her rise through the male-dominated music scene of late 1960s Nashville.

Thoughts: And we have a new least favorite logline of the entries so far. I feel like you can cut and paste these loglines and just add a new quasi formerly big celebrity each time. Dolly Parton does have her fans, though.

13 votes

Pikesville Sweep by Brendan McHugh

After a young, newly widowed janitor in a small mining village is unexpectedly elected Mayor, she navigates a new relationship with a mysterious man from the city and tries to determine how to use her new position of power to confront the corruption that has plagued the town for years.

Thoughts: This one doesn’t have that big shiny hook in it anywhere. Which means it’s an execution-dependent screenplay. It used to be that if one of these made the Black List, it was a really good script because it meant it was so good that it overcome its weak logline. But these days, that’s less the case. So I’m lukewarm on this entry.

13 votes

Wild by Michael Burgner

A young woman is determined to protect a thief on the run when he holes up in her small town, even if it means revealing a darker, more violent secret of her own.

Thoughts: Lots of dark secrets in this Black List! I hope everybody can see for themselves how the lack of a special attractor (or a “hook”) hurts a logline. When there are little to no unique elements in a logline, we’re less likely to want to read it. I’d argue this logline doesn’t have a single unique word in it.

12 votes

Clementine by David L. Williams

Set in real time, a Colombian mother barely escapes a pawn shop shootout and goes on the run from her violent ex-husband, a terrifying mob boss, and a bloodthirsty hitwoman sent to collect an overdue debt, all while trying to keep her diabetic daughter safe.

Thoughts: HEY! It’s longtime Scriptshadow reader and contributor, David Williams. So happy to see him on the list this year. The man had to run into a grumpy Carson each and every time he submitted scripts for Amateur Showdown. But regardless of whether he advanced in competitions or not, he was never bitter. He was the opposite. He was always positive. And I have no doubt in my mind that that’s why he’s on the list today. He’s a great example to screenwriters everywhere about what happens when you keep doing the work and you stay positive. Congrats David!

12 votes

Fog of War by Peter Haig

When a retired war journalist returns to the outpost where her son was stationed to investigate the mysterious circumstances surrounding his death, she uncovers unspeakable horrors.

Thoughts: Echoes of In The Valley of Elad here. And that’s why I’m worried about it. These dark super serious movies about investigating death are tough sells, especially in a time like this where everyone is looking for respite from all the darkness. The script will have to be really good to overcome this issue.

12 votes

Jingle Bell Heist by Abby McDonald

At the height of the holiday season, two strangers team up to rob one of New York’s most famous department stores while accidentally falling in love.

Thoughts: I like the irony of doing something bad on the ‘goodest’ holiday of the year. But, personally, as I’ve told you guys here before, I like my holiday movies to be heartwarming and uplifting. My favorite Christmas movie of all time is the ultimate heartwarmer, It’s a Wonderful Life. With that said, I’ll probably review this one before Christmas and, hopefully, it will prove me wrong.

12 votes

Let’s Go Again by Colin Bannon

When her domineering director makes her film the same scene 148 times on the final night of an exhausting shoot, actress Annie Long must fight to keep her own sanity as she tries to decipher what is real, and what is part of his twisted game.

Thoughts: One of the wildest writers out there right now. Definitely a guy who comes up with interesting concepts. This one is no different. It’s got a high concept feel and yet it’s completely original. Nobody’s ever written a movie like this before. That’s always a good sign. My only issue with Bannon is that his third acts get a little too wild for me. And this – “must fight to keep her own sanity” – sounds like it will continue that tradition.

12 votes

The Americano by Nico Bellamy & Chase Pestano

An everyday guy who accidentally starts working as a barista inside the CIA headquarters building gets lured into a spy mission by a beautiful secret agent, known only to him as Caramel Macchiato.

Thoughts: This logline made me chuckle. Again, guys, this is the power of irony in concept creation. When you think of something as big and sophisticated at the CIA, you don’t think about the fact that there’s a coffee shop inside the building. And baristas work there. It’s the perfect contrast. And the idea that one of these baristas gets recruited into a spy mission is really clever.

12 votes

The Boy Houdini by Matthew Tennant

New York, 1889. When young street urchin and aspiring magician Harry Houdini discovers a mysterious puzzle-box, he must use his talent for illusion and escape to unlock the box’s powerful secrets and keep it from the hands of a vengeful occult sorcerer hot on his tail.

Thoughts: Smart move to write a Houdini spec. Back in the 2000s, Houdini was a very popular subject in the spec world. But since none of scripts ever became movies, he fell out of fashion. However, he’s still a known property – an operating IP – and he’s an interesting guy whose life is perfect for movies, since he’s a magician. Color me curious.

11 votes

Match Cut by Will Lowell

While filming on location in Rome, a movie stuntman is mistaken for an infamous assassin, leading to 48 hours of madness as he’s chased through the city by both gangsters and police.

Thoughts: Okay, this is an example of a concept WITHOUT IRONY. Or maybe that’s a strong statement. It doesn’t have enough irony may be a better way of putting it. A movie stuntman is fully capable of running and fighting, shooting guns, and racing cars away from pursuers. So there’s little irony to the fact that he gets mistaken for an assassin. We all know he’s probably going to be okay since he does most of this stuff every day at work anyway. Maybe if they had said, “the world’s worst movie stuntman,” I’d be more interested.

11 votes

Mega Action Hit by Sean Tidwell

After Hollywood’s leading action star hits his head on set and wakes up thinking he’s a real-life action hero, he embarks on an international mission to track down a real stolen nuke before it’s too late.

Thoughts: This concept feels a little dated – like it could’ve conceived in 1998. But it is high concept. And it sounds a little funnier than Match Cut. It’s weird how The Black List always has two of these concepts back to back that are carbon copies of each other. It’s got to be because of some glitch in the voting process.

11 votes

Semper Maternus by Laura Kosann

On a private island off San Francisco, a nanny goes to work for a mother who is one of America’s most powerful tech entrepreneurs. Things slowly begin to devolve as the mother’s hyper-monitoring and surveillance become suffocating.

Thoughts: Another Ex Machina premise! And I’m not mad! I like these premises. They’re one of the most ideal setups for a budget-conscious movie. And I love nanny stories dating back to The Hand That Rocks The Cradle. Grab me a cradle on Amazon cause I’m down for this adventure.

11 votes

Subversion by Andrew Ferguson

When her family is abducted, a disgraced submariner must pilot a narco submarine to its destination in less than eight hours or her husband and daughter will be killed.

Thoughts: Andrew is a trusted member of the Scriptshadow newsletter and it looks like he’s been paying attention to my ramblings! As this script, more than any other script on the list, has the GSU in place! Nice job, Andrew!

11 votes

Total Landscaping by Woody Bess

A day in the life of the employees of Four Seasons Total Landscaping and its neighboring businesses on November 7th, 2020: the day an average, working-class strip mall in East Philadelphia became the focal point of the most divisive presidential election in American History.

Thoughts: I was thinking the other day. What we really need in movies right now? More than anything else? Is more politics. Cause I don’t think there’s enough. For those new to the site who don’t know me, I am emitting extreme amounts of sarcasm right now. I just can’t get pulled down into that depressing hole anymore. Concepts like this literally make me physically ill. With that said, I know many people in the industry can’t get enough of this stuff. So don’t go by my assessment of these concepts.

10 votes

Cheat Day by Emma Dudley

When a young woman in a decade-long heterosexual relationship realizes she needs to explore her bisexuality, she and her boyfriend institute a “Cheat Day:” 24 hours in which they can do whatever–and whomever – before deciding whether to get engaged or break up.

Thoughts: Echoes of Hall Pass, which should’ve been better than it was (million dollar spec that movie, by the way, from the original Project Greenlight winner, Pete Jones). What I loved about that movie was how the guys were so excited to have their hall pass but then they couldn’t get laid if they paid someone. The problem with these concepts is always the same. The guys given the chance to be with someone else never actually do. Someone needs to write a version of this concept where they actually have sex with other people. That’s where you’re going to find a truly compelling movie.

10 votes

Going for Two by Kevin Arnovitz

An openly gay NFL quarterback finds his meticulously-planned life upended on and off the field when he falls for a charming high school teacher during the most important season of his career.

Thoughts: Well I can definitely see why this made the Black List. But I’m not reading it unless it’s the real life story of Bachelor fence-hopper Colton Underwood. That’s a biopic I can get behind. No pun intended.

10 votes

Popular by Marley Schneier

GOP strategist Lee Atwater won the presidency for George H.W. Bush in 1988, and his campaign changed politics forever–and gave him the worst reputation in America. Now, Lee is on his deathbed, and he needs to tell God his side of the story… before it’s too late.

Thoughts: It took waaaaay too long to get to another political script. At most, it should’ve taken 1 slot. The fact that I had to wait this long is a crime. Can’t wait to not read this one.

10 votes

Ravenswood by Evan Enderle

To save her friend, a maid in a decaying manor must unravel the secrets of its inhabitants while confronting spirits, her own terrifying abilities and the very real horrors of Depression-era America lurking outside the door.

Thoughts: If this is a ghost story, it’s one of the most roundabout ways of describing a ghost story that I’ve ever come across. But if it’s got ghosts, I’m in! By the way, note how much better those high ranking concepts were compared to what we’re getting down here in the lower ranks. There’s clearly a difference in quality.

10 votes

The House in the Crooked Forest by Ian Shorr

A mother and her young son fleeing Nazi-occupied Poland are forced to take shelter from a blizzard in an isolated manor, where they discover the Nazis may be the least of their worries.

Thoughts: Ian is a longtime Black List contributor and he tends to have high concept ideas. This one is no exception. My only issue is that he should tell us what’s in the manor. Let us decide if it’s worse than Nazis. We shouldn’t have to take the logline’s word for it.

10 votes

The Pack by Rose Gilroy

A group of documentarians braves the remote wilderness of Alaska in an effort to save a nearly extinct species of wolves. When the crew is brought back together at a prestigious awards ceremony, tensions flare as a deadly truth threatens to unravel their work. The team lived through the harsh elements of the wild but will a secret they share survive the night?

Thoughts: What. Is. THE SECRET!? It’s not a logline unless you tell us what the secret it. The secret is the hook. You can’t deny people that.

10 votes

Vitus by Julian Wayser

In 1518, a Dancing Plague overtook the city of Strasbourg in the Holy Roman Empire. Hundreds of people danced themselves to death over the course of a summer and no one knows why. Encircling medieval medicine, the uncanny, and the origins of mass hysteria, Vitus is a wildly visual exploration of a crucial (but little-known) moment in European history.

Thoughts: Highly curious about this one. I’ve heard of the dancing plague before. I always thought it was really weird. Whenever you have something this bizarre, it opens the door to tell a story about it. So kudos to Wayser for identifying the potential behind this weird historic moment.

10 votes

What We Become by Amy Jo Johnson

A successful author/wife/mother plans a trip to a bucolic island to crack her next book and finds herself in a surprising situation.

Thoughts: The Scriptshadow part of me wants to grumble about how the logline needs to tell us what the surprising situation is. However, I want to share a quick story with you. When I first moved to LA, I was out one night with a buddy and we stumbled upon a couple playing pool. The girl, shockingly, was Amy Jo Johnson (Power Rangers). The guy, it turned out, was not her boyfriend, but rather, her brother. We played a game of pool together and Amy was the sweetest most fun person you’ve ever met, joking and giving us crap the entire game. To this day, I kick myself for not getting her number but I just figured, what would a Hollywood actress want to do with me? These days, I know that you never know unless you ask! So you know what? This is one logline where I don’t care that the writer didn’t tell us what the hook was. Amy Jo Johnson, you get a pass! Also, apropos of nothing, are you single?

10 votes

Who Made The Potato Salad? By Kyle Drew

A family’s Christmas dinner goes awry when a xenomorphic demon starts to duplicate and imitate each member of the family. What does it want? To show them their greatest fears.

Thoughts: I read these scripts all the time and while they make pretty good loglines, trying to write them is bit of a demonic task in its own right. They all end up reading the same. So you have to have a very unique voice to make them work.

9 votes

It’s a Wonderful Story by Alexandra Tran

In the aftermath of WWII, a traumatized Frank Capra and Jimmy Stewart use the making of IT’S A WONDERFUL LIFE to attempt to find a way back into normalcy.

Thoughts: It’s like the Black List is reading my mind now! I told it my favorite Christmas movie was It’s a Wonderful Life, then 10 loglines later, it’s giving me an It’s A Wonderful Life script. Wait a minute. Does this have something to do with AI? Is this ChatGTP? Has the singularity almost begun? We are all in the Matrix.

9 votes

The Sister by Alexander Thompson

Identical twins Aurora and Gabrielle live in a secluded commune where all twins are raised knowing that in adolescence, one of the two of them will abruptly turn into a terrifying monster. Discovering the full truth of their situation one fateful night, the sisters plot their escape into an outside world they know little about.

Thoughts: Getting some strong young adult novel vibes here. I have issues with concepts where the buy-in is based more on the writer feeling like they’re granted an automatic buy-in rather than the buy-in actually making sense. It feels like the only reason one of the twins turns into a monster is because the writer needs that to happen for their story. I might be wrong. But unless there’s a believable reason for why that happens, this one probably isn’t for me.

8 votes

An Oakland Holiday by Yudho Aditya & Emma Dudley

When a neglected and lonely Southeast Asian Princess goes undercover in an Oakland high school to live out her dream of being a normal teen, she discovers that happy endings come with many hard lessons about life, love, and humility.

Thoughts: I don’t know about you. But many of my dreams start off with the words, “An Oakland Holiday.” This is a tried and true concept. Special Person hides out in normal society. It’s samey. But it usually works. And this one has a slightly different angle with the Asian connection.

8 votes

Better Luck Next Time by Kristen Tepper

Two best friends run a successful underground service taking womens’ toxic exes on humiliating dates, but their friendship is put to the ultimate test when an old mark plots his revenge.

Thoughts: I feel like I’ve heard this one before. Either someone on the site pitched it to me or we’re all drawing ideas from the same popular culture pot and none of us is as original as we think we are.

8 votes

I Love You Now And Forever by Robert Machoian

After exhausting all financial options to save their dying daughter, Frank and Abby are forced into a final act of desperation: rob a local bank.

Thoughts: What would you do to save someone you love? Always an interesting question and, therefore, potent fuel for a movie. However, robbing a bank seems pretty standard. Didn’t John Boyega just make a movie with this exact same setup. Denzel has also made one before. John Q I think it was called? Not original enough for my taste.

8 votes

Jerry! By Greg Roque

One man ran what was declared to be the worst TV show of all-time. Responsible for the degradation of American society. All while topping Oprah in the ratings. This is the over the top, insane true story of how Jerry Springer went from ambitious young attorney, to the Mayor of Cincinnati, to the undisputed King of Trash TV. And along the way, accidentally helping to create the world we live in today.

Thoughts: You know how I feel about biopics. But Jerry Springer was a pretty funny footnote in American TV history. They would literally just let people fight each other on stage, lol. Imagine if they tried to air that show now.

8 votes

Pop by James Morosini

A kid blackmails his favorite pop star into being his best friend.

Thoughts: Shortest logline on the list. It also covers familiar territory. The last few years we’ve had movies about people blackmailing or stalking social media personalities. A pop star feels like a 2003 movie. But, it all comes down to execution. If the script’s good, it will make up for it.

8 votes

The Demolition Expert by Colin Bannon

Blasting out of prison after being double crossed by the Mastermind of a heist, a Demolition Expert uses his genius with explosives to enact revenge on the Caper Crew who set him up while simultaneously picking up the pieces of his personal life.

Thoughts: Why do I get the feeling that Michael Bay is going to take a serious look at this one?

8 votes

The Homestead by Bradley Kaaya Jr.

A troubled bi-racial, inner-city teen is sent to live with his white, conservative grandfather on his ranch for the summer. Things take a turn when the two are forced to overcome their generational and racial differences while defending the ranch from a ruthless, backcountry gang.

Thoughts: I had no idea they were making a real life adaptation of Webster.

8 votes

The Twelve Dancing Princesses by Becca Gleason

A horror thriller spin on the Brothers Grimm fairytale in which 12 female college students fight against a group of dude bros trying to take over their female-only space.

Thoughts: Whoa, these last couple entries are like taking a time machine back to the 2019 Black List! Down with the dude bros! Actually, “Down with the Dude Bros” is a better title.

8 votes

Undo by Will Simmons

A down-on-his-luck former getaway driver comes into possession of a mysterious watch that allows the user to go back in time by one minute. As he starts to uncover its uses and gets pulled into one last heist by his former crew, a dangerous group after the technology gets on his tail and will stop at nothing to get the watch back.

Thoughts: I’ve always been intrigued by mini time travel stories. My worry with them has always been that, not surprisingly, they feel too small. There *is* something to this idea, though. I think he needs to be a race car driver though, not a getaway driver. This is the year of sports scripts, right? It’d be cool if you could keep rewinding on the race course to correct your mistakes.

8 votes

Weary Ride The Belmonts by Josh Corbin

After staging his death many years ago, an aging gunslinger is forced to reunite with his outlaw daughter during the dying days of the west.

Thoughts: I could complain about the lack of a hook here. But Westerns rarely have hooks to them. So it’s one of those delios where you’re going to have to read the script to see if it’s good. Who’s going to take care of that? Oh yeah, that’s me. I am literally the only person who reads screenplays in Hollywood.

7 votes

42.6 years by Seth Reiss

After waking up from a failed experimental lifesaving procedure in which he was cryogenically frozen for 42.6 years, a young man realizes he wants his ex-girlfriend back. He’ll have to overcome the fact that while he hasn’t aged a day, she’s lived an entire life without him

Thoughts: Seth Reiss is one half of the writing team who wrote The Menu. And you guys know how much I liked that script. I’m trying to get a grip on the genre here. But “42.6” tells me that it’s probably a comedy. It’s certainly a unique idea, an update on Harold and Maude. Could be good!

7 votes

Break Point by Zachary Joel Johnson

Courted by colleges and sponsors alike, a burnt-out tennis prodigy fights to maintain dominance against her Academy rival as she hurtles toward the existential decision of turning Pro–a choice that will force her to double down on her dream or walk away from the future she’s fought for.

Thoughts: Tennis scripts are everywhere! And yet they still haven’t made a good tennis movie. Go figure. I’m looking for the unique attractor in this one. I’m slightly confused in that the main character seems young but they’re also a burnt out veteran? One thing I’m learning, though, is that women rule when it comes to tennis scripts. Sorry dudes!

7 votes

Caravan by Lindsay Michel

During the Tang Dynasty, a young Persian woman joins a Silk Road caravan to solve the mystery of her father’s disappearance‚ but must fight for survival when her fellow travelers realize there is a shapeshifting demon hiding in their midst.

Thoughts: Tennis and demons are the theme of Black List 2022. A tennis demon script anyone? If you’ve got a good idea, pitch it to me. I like the setting here. I don’t know much about it and that’s one of the things I like when I open a script. I like to learn about new things. Be taken to new places. So I’m willing to give this one a try.

7 votes

Gather the Ashes by Vikash Shankar

Two brothers, Dev and Siddharth, hope to break free of London’s foster care system when they inherit their estranged family’s old farmhouse in India, but they find something sinister lies in the roots of their family tree as they attempt to discover their past.

Thoughts: Another sinister thing hiding in the shadows. Secrets, demons, sinister things, too many double faults, dude-bros. I’m trying to keep up with the madness that is Black List 2022!

7 votes

Himbo by Jason Hellerman

A naive male stripper attempting to start his life over finds himself in the crosshairs of his boss’ increasingly violent divorce.

Thoughts: This one should give all of you hope because the writer doesn’t have a manager, an agent, or a producer. It made the Black List entirely on its own merit. How bout that!

7 votes

It’s Britney, B—ch by Cerina Aragones

A dramatic and musical character study of global pop icon Britney Spears, leading up to her very public unraveling at a Tarzana hair salon, and her recent courtroom victory to win her freedom back.

Thoughts: If someone didn’t write it, ChatGPT was going to. We finally got our Britney Spears biopic everyone. Stab me in the face baby one more time.

7 votes

Life of the Party by Julie Mandel Folly & Hannah Murphy

In this contemporary reimagining of Frankenstein, two teenage feminists struggle to create the perfect boyfriend, only to watch their experiment deteriorate as he succumbs to the ultimate perpetrator of casual high school misogyny: the football team.

Thoughts: This one sounds like it could be fun. A reimagining of Weird Science.

7 votes

Ripple by Max Taxe

When a time traveler starts meddling with the past just as Miles finally meets the love of his life, he must battle ever shifting timelines to find her again.

Thoughts: I’ll read anything with time travel but this logline is confusing. It doesn’t say in the first part of the logline that she disappears. So why does he need to find her again?

7 votes

Wildfire by Chaya Doswell

After accidentally starting a wildfire, 7-year-old Lu, mute and from an abusive home, slyly tricks Merribelle, a hardworking trans woman, into kidnapping her – sparking a beautifully unexpected bond with a devastating expiration date.

Thoughts: This one covers some huge topics. Muteness, abusiveness, a trans woman. And yet the thing I’m most hooked by is the wildfire.

6 votes

Below by Geoff Tock & Greg Weidman

Fresh out of a spell in prison a man attempts to set his life right by working a mysterious job that requires him to seek out life forms hidden amongst us.

Thoughts: Okay, I kinda dig this one. We’ve seen a lot of movies where people come out of prison and get blue collar jobs that they hate because they pay nothing. This throws a twist into that. A guy gets a job looking for hidden life forms. That’s up my alley.

6 votes

Black Dogs by Kieran Turner

Based on the novel by Jason Burhmester. In 1973, Led Zeppelin was robbed of nearly a quarter million dollars in cash while playing a series of concerts in New York City. The case was never solved. We follow four young friends from the streets of Baltimore as they attempt to pull off what is possibly the most brazen heist in Rock & Roll history.

Thoughts: I still think that script a Scriptshadow reader wrote about a heist of Jim Morrison’s grave was the best rock and roll heist script I’ve read. But this sounds pretty cool too. Although I wonder how people are going to sympathize with characters robbing beloved legends.

6 votes

Black Kite by Dan Bulla

After a devastating wildfire wipes out a small California town, a teenage girl is missing and presumed dead. A year later, an obsessive mother and cynical arson investigator begin to suspect that she’s still alive…and in the clutches of a predator.

Thoughts: Lot going on in this idea. I’m not sure if the variables all come together harmoniously. But it does feel like it’s going for it. As long as you’re going for it with your idea, you’re better off than writing something safe and neutral.

6 votes

Chatter by Chris Grillot

Stranded in a small Cajun town, a young mother battling a painkiller relapse must fight to save her daughter from a demonic Tooth Fairy.

Thoughts: I’m noticing with some of these lower ranked scripts, the loglines have buzzwords but they don’t come together nicely. But! “Chatter” does bring us another demon. I think we can safely say, at this point, it’s the year of the demon!

6 votes

Craigshaven by Nicole Ramberg

A troubled teen must confront a local legend when the reappearance of a missing classmate and a fabled ghost ship unravel clues to her own mother’s disappearance.

Thoughts: I would rebuild this logline to focus exclusively around the ghost ship if possible. I don’t think you can bring up a ghost ship casually in a logline (“there’s a missing person…. Oh and then there’s a ghost ship by the way…”)… It’s got to be the central focus.

6 votes

Eternity by Pat Cunnane

After death, everybody gets one week to choose where to spend eternity. For Joan, Larry, and Luke, it’s really a question of who to spend it with.

Thoughts: This choice is easy. Baby Yoda and ChatTPG.

6 votes

Marriage Bracket by Liv Auerbach & Daisygreen Stenhouse

Ten years after a group of girlfriends bet on which of them would be the last to get married, their adult lives and relationships are completely upended when they discover the $80 they drunkenly invested in Bitcoin is now worth $5.2 million.

Thoughts: A fun idea with a couple of problems. Bitcoin is no longer a positive word. But it is a cool way to create a ‘windfall’ storyline. Second problem is, what does a bet about who will be the last to get married have to do with investing money?

6 votes

The Seeker by Camrus Johnson

A childhood folktale comes to life when children of the neighborhood start to go missing after playing hide and seek. A group of friends known as “The Finder Four” set out to get answers, but instead, find themselves sucked into a fantasy fear-factor world with only one way out… Based on Daka Hermon’s Scholastic YA Novel, HIDE & SEEKER.

Thoughts: Concept gets a little too complicated as the logline goes on but kids going missing during hide and seek is a good idea.

6 votes

The Trap by Julie Lipson

Twin-sister trapeze artists wrestle their own inner demons amid the push-pull of career, stardom, and family, all while performing in the most harrowing production of their lives.

Thoughts: We’ve got our second set of twins on the list. This is the first trapeze concept on the Black List in over five years, if my memory serves me correctly. If this story explores the reality of being a trapeze artist, I’ll be into it. But if I read this and I know more about trapeze artists than the writer, we’ve got a problem on our hands. This is something that happens often, by the way. A writer will write about a topic and the reader will end up knowing more about it than they do. This can NEVER happen. You must be the extreme expert on your subject matter.

6 votes

You’re My Best Friend by Mary Beth Barone & Erin Woods

Lily is mature, thoughtful, artistic, and… awkward. Rosie is sweet, caring, and popular with dreams of being a star. When Lily breaks down in tears on her 15th birthday because she has no friends, her Aunt Beth (a hot shot at a big movie studio) devises a plan. Aunt Beth agrees to jump start Rosie’s acting career as long as she can convincingly play the role of a lifetime: Lily’s best friend. Aunt Beth has the scheme and Rosie has the talent. All they have to do is get away with it.

Thoughts: This feels a bit first-scripty. I’m not sure I understand the logline, to be honest. Which is a good lesson, by the way. A lot of people think that the more you write, the more clear your idea will be. When, in actuality, the opposite is true. The more you distill it down, the clearer it will be to the potential reader.

The scripts I’m most looking forward to are Pure, Beachwood, Baby Boom, Jambusters, White Mountains, Goat, Clementine, Let’s Go Again, Vitus, The Americano, Semper Maternus, Subversion, and Undo. I’m too close to Court 17 to be able to judge it objectively. What about you guys? What do you want to read???

If you’re interested in getting a logline consultation from me, they’re $25 and they include a 150-200 word analysis, a 1-10 rating for both concept and logline construction, and a logline rewrite. If you want a full screenplay consult, I offer that as well. E-mail me at carsonreeves1@gmail.com and we’ll get started right away!