Search Results for: F word

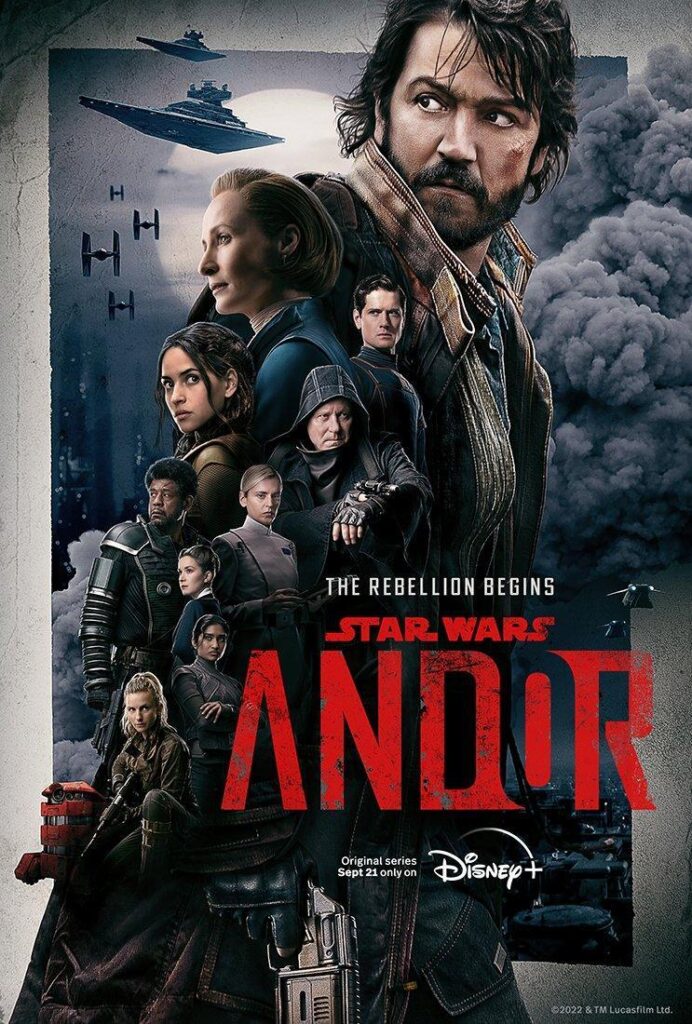

”Andor” asks, can a Star Wars experience without humor or padawans who hate sand entertain a rabid fanbase desperate for a good Star Wars show?

Genre: Sci-Fi Fantasy (TV show)

Premise: After a thief kills two employees from a large corporation while looking for his missing sister, he becomes hunted by the company on the backwater planet where he lives.

About: It’s finally here! Andor, the series. I’ve talked about it endlessly on the site. Tony Gilroy, who reportedly saved Rogue One from original director, Gareth Edwards, was gifted this show as his reward by Lucasfilm head, Kathleen Kennedy. Despite Gilroy insulting poor Star Wars every chance he gets and making the world’s most confusing statement about how the timeline in “Andor” is going to work, the show finally debuted today.

Writer: Tony Gilroy

Details: This review is for the first 3 episodes, which are each about 30 minutes.

Let us start by stating the obvious.

Before this series was announced, nobody was asking for a Cassian Andor show.

Which makes you wonder why they wanted to make it so badly. Lucasfilm has become infamous for terminating in-development Star Wars projects. So why were they so determined to get this one to the finish line?

Who knows? Most of you will probably say, “Who cares? As long as the show is good.”

To this, we can agree. I may not have asked for Andor but you can bet Chukhuh-Trok’s hunting spear that I’d love to be proven wrong. Probably more than anyone on this planet, I want to love a Star Wars show. And, from what we’ve been told, this show was made more for my demographic than any Star Wars project yet.

Are we ready for this?

Okay, let’s dig into Andor!

We meet Cassian Andor on some planet run by what Amazon might look like in a thousand years. Andor heads to a brothel where he appears to be looking for his sister, who may have worked here at one point. He doesn’t get any information on her so he leaves, and is immediately confronted by a couple of drunk-with-power Amazon employees. He quickly kills them both. Take that, Bezos!

Andor then heads back to his current planet of residence where he’s putting together some plan that is so secretive even the audience is not allowed to know it. In between scenes of him sneaking around and never allowing his voice to rise above 3 decibels, we cut back to when he was a kid on some planet living with a bunch of other kids and they discover a crashed ship.

Back at Amazon, a middle management type wants to sweep these employee murders under the rug. But a young ambitious dude in the company wants to kill the murderer in the hopes of propelling himself up the company ladder. So he recruits a dozen soldiers and heads off to Cassian’s planet to find him.

Cassian’s super-secret plan finally reveals itself when he meets with a mysterious rich guy named Luthen Rael. Cassian thinks he’s selling Luthen a star-thingamacalit, after which he’ll use the money to escape to some place far away. But it turns out Luthen has other plans for Cassian. Seeing how crafty this guy is, he wants to recruit him into his shadowy organization. Cassian has to make a decision fast – yes or no? He decides ‘yes,’ and that is the end of our third episode.

I was worried about two things going into this show.

1) That Cassian Andor isn’t a very interesting character.

And…

2) That this show would be way too serious.

I am sad to report that “Andor” confirmed both of these fears. Much like Tion Medon’s infamous botched dental visit, it’s a big fat whiff on each front.

Cassian is boring. He’s active, which is good. But if we never understand what our character is being active for, it doesn’t really matter. Being ultra-mysterious about who your main character is is one of the riskier moves in screenwriting. Because you’re basically saying, “You must like my character even though you know nothing about him or what he’s doing.”

There are examples of this working but they’re few and far between.

On top of this, the show is more serious than Emperor Palpatine when he’s drawing up his latest galaxy takeover. I think there were two attempted jokes in 100 minutes. And they were highly neutered. This is something I tried to warn the Star Wars fan base about. If you go super dark with Star Wars, it’s no longer Star Wars. An essential component of Star Wars’s makeup is fun. And this show is about as fun as when Malakili watched Luke kill his pet Rancor.

The closest to fun we get is the droid, B2EMO, and while I’d anoint him as my favorite character in the series so far, he’s got five minutes of screen time.

So is there anything good about this show, Carson?

I’ll say this. The dialogue is way better than any of the other Star Wars shows. There’s a level of sophistication you’re not used to seeing in this franchise. For example, there’s a scene where Andor comes to a work friend and asks him to provide an alibi for why he wasn’t at work earlier.

The dialogue is not framed in a clunky on-the-nose manner where Andor says something like, “I need you to help me with an alibi. I flew off to another planet which is why I missed work and now I need you to tell Boss Doug that I was hanging out with you.”

Instead, the dialogue is framed as if it really happened. So Andor immediately jumps in with, “I was at your house yesterday. We drank all night. You got mad at me because I bought cheap liquor.” “I would’ve yelled at you for bringing cheap liquor. We were drinking [different booze] instead.” In other words, they set up the alibi by speaking as if it really happened rather than asking for help and then coming up with a story together.

With dialogue, you’re always looking for ways to make the exchange different somehow. You want to avoid straightforward, Character A: “This is what I have to say,” Character B: “And this is how I respond to that” dialogue if possible. You could tell Gilroy is a step above all these newbie screenwriters that Star Wars has been hiring to write their shows. At least in the dialogue department.

Ironically, that same knowledge hurts Gilroy in the storytelling department. What usually happens when you get older as a writer is you show more restraint. You don’t feel the need to constantly titilate the audience every scene. You trust yourself and therefore take your time setting up the bigger plot developments.

But what sometimes ends up happening is you cross the Rubicon and show so much restraint that huge chunks of scenes go by without any payoff. We’re watching you setup and setup and setup and setup and it’s like, “Dude! Give us something for all the hard work we’re doing!”

I get the impression that Gilroy is playing to the highest common denominator here – the 60 year old intelligent veteran moviegoer who’s seen it all and is, therefore, willing to make the trek down Patience Lane. It’s a risky game to play in a franchise built off a never-ending supply of entertaining moments.

I would not have watched Episode 2 if they had only posted the first episode on Disney Plus today. I wouldn’t have even watched Episode 3 if they’d posted the first two episode on Disney Plus today. That’s how slow the story develops.

To Gilroy’s credit, all the things he was setting up in episodes 1 and 2 start to pay off in episode 3. This is the episode where the Amazon Corporation sends their soldiers to Andor’s planet to find and kill him. Gilroy did a really good job building up to this confrontation. What I enjoyed most about it was he made the whole thing just as scary for the Amazon soldiers as he did the locals. These soldiers are inexperienced. They’re 12 in a city filled with thousands of people. At any moment, if the people decide to revolt, they’re screwed.

That combined with the mystery of where Andor was going and who he was meeting created a tense atmosphere throughout the episode. It helped me see the potential of the series I was unconvinced it possessed in the first two episodes.

This has led me to a very confused place going forward with Andor, and with Star Wars in general. The Obi-Wan Kenobi show was a mess. Those rookie writers shouldn’t have been let anywhere near a franchise this big. The Boba Fett show was some of the worst writing I’ve seen on a show with that kind of budget. The Mandalorian is uneven but has some good episodes. It’s written well at times.

I would say that Andor is the most sophisticated written Star Wars show by far. I’m just not sure that’s showing the dividends it needs to after three episodes. Clearly, Gilroy knows how to write a scene. But is his overarching narrative as compelling as he thinks it is? I’m not sure. And is his main character as interesting as he thinks he is? Probably not.

I think this begs the question: Does Gilroy mesh with the Star Wars brand? Or is he pulling a Rian Johnson, where you hijack a franchise to tell the story you want to tell rather than the story that’s right for the franchise?

I’ll probably check back in with you guys at the season midpoint to give you better answers to those questions. In the meantime, tell me what you thought of Andor.

[ ] What the hell did I just stream?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the stream

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Andor is yet another example of why all writers should seriously reconsider adding flashbacks to their story. We saw this in Boba Fett with the silly sand people flashbacks. We see it here with all this time spent on Cassian’s childhood that doesn’t tell us anything we couldn’t have already imagined ourselves. You have to ask the question, is what the flashbacks give you worth the momentum-stoppage they take from you? In this case, the answer is clearly no. The flashbacks dragged along. I’ll never say never. But, in my experience, flashbacks almost always take more from the story than they give.

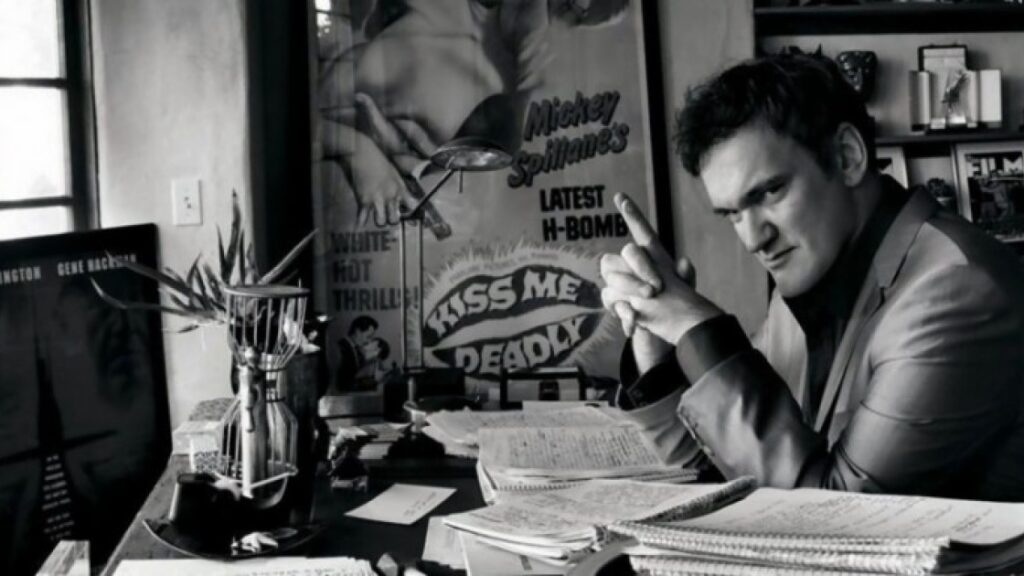

Write dialogue like this guy!

Write dialogue like this guy!

The bulk of the Scriptshadow Dialogue book is written. The one chapter I’m still working on is this chapter I’m tentatively titling, the “verbal arena.” This is the chapter that’s going to teach you how to write like Tarantino, Woody Allen, Diablo Cody, Aaron Sorkin. I know some of you will scoff at this but that’s my goal. Sure, I can’t make you as good as those writers. But I can give you the tools to get a lot closer to them than you are now.

So, I’ve been watching a lot of “verbal arena” movies – flicks where the dialogue is inventive and fun and memorable – trying to decode that unique dialogue Matrix within. The other night, I watched Barry Levinson’s, “Diner,” which I hadn’t seen in 20 years and didn’t remember well. But I’ve heard a lot of people talk that movie up as an example of great dialogue.

Man, I have to say, I was really disappointed. Outside a couple of minor exceptions (“Where’d you get this attitude?” “Borrowed it. I’ll have it back by midnight.”) it was mostly mundane middle-of-the-road conversation. I *was* shocked when I realized just how much Swingers borrowed from the film. But, other than that, it was an average movie with, maybe, slightly-better-than-average dialogue.

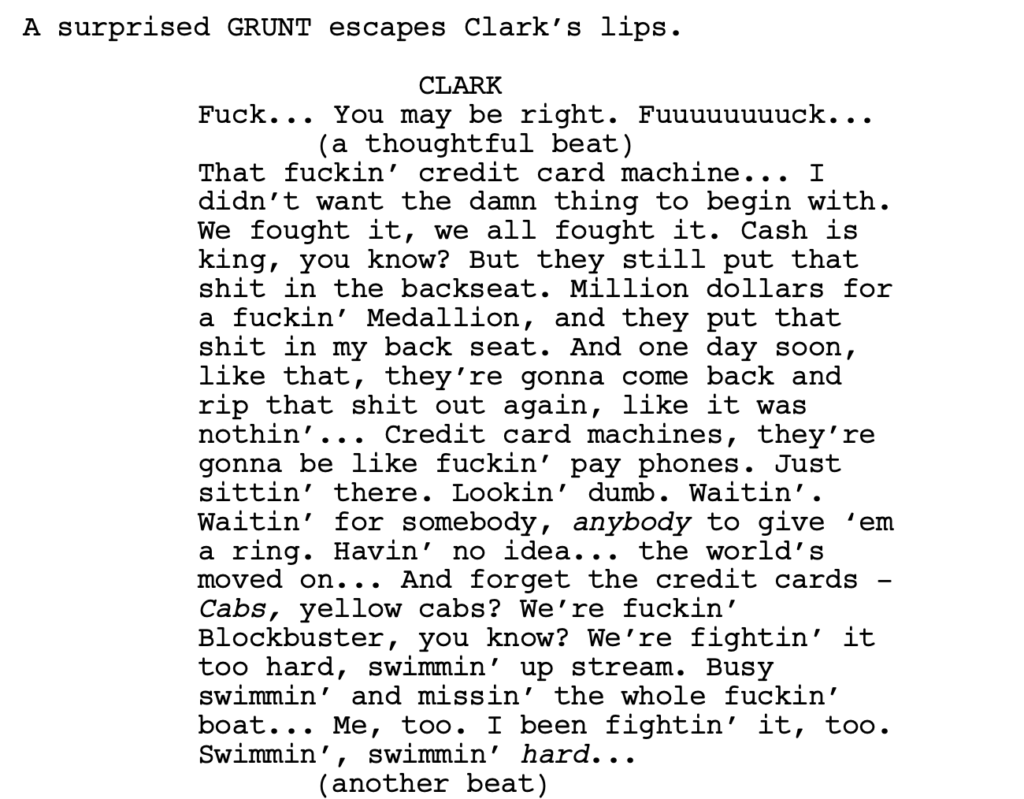

At that point I was going to go to sleep but then I remembered a script whose dialogue had always impressed me and decided to bust it open and read a few pages to see if I still felt the same way. The script is called “Daddio.” It was a high ranking Black List script from five years ago.

Let me tell you: I’ve been reading A LOT of dialogue over the past few weeks — from amateur scripts, to pro scripts, to pantheon level classic movie scripts — I’m not exaggerating when I say the dialogue in the first ten pages of this script blows almost all of those scripts away.

So much so that I’m going to spend the next few days ONLY diving into this script and trying to figure out what Christy Hall is doing that makes her dialogue so good.

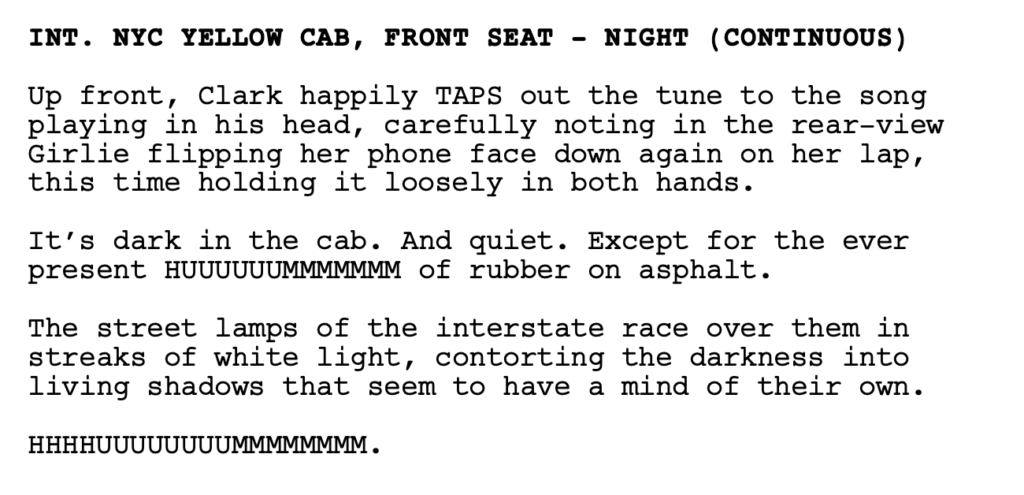

Now, the scene that I’m about to show you is a little different in that it’s more a monologue than a dialogue. But it’s so good I think it’s worth highlighting. In the scene, our main character, Girlie, has just landed at JFK airport, and is going to meet a guy who, from the limited text messages we’ve seen between the two, doesn’t seem all that into her, which is something she’s trying not to think about too much.

The cabbie guy becomes a temporary distraction from this potential down-the-road problem. The script takes place entirely in the cab as we ride from JFK to this guy’s place. It’s one long conversation. What we’re seeing here is the beginning of the conversation.

The first thing you want to pay attention to here is the organic nature of the conversation. This isn’t a “normal” scenario. For example, this isn’t two people waiting at a valet stand for the valet to pull their car up. It’s a long cab ride. There’s a lot of down time involved. Conversations are different in down time. They’re not as immediate or necessary. People are more likely to ramble, which is why this scene works, whereas, if it were at the valet stand, a long philosophical rant about rideshare apps taking over the world would feel try-hard.

My point is, know the situation in order to know what kind of dialogue you can use. The rambling nature of this dialogue works because it’s organic to the situation.

The first segment of Clark’s dialogue is the most “normal.” It’s a guy talking about how his day sucked, he didn’t get a lot of good fares, and he’s unhappy about this payment switch to credit cards cause he makes less money on it. Most writers could write this segment. Although, I thought the “Monopoly money” choice was thoughtful. More creative than saying, “Cash.” Look for these little opportunities to replace standard words with something more imaginative.

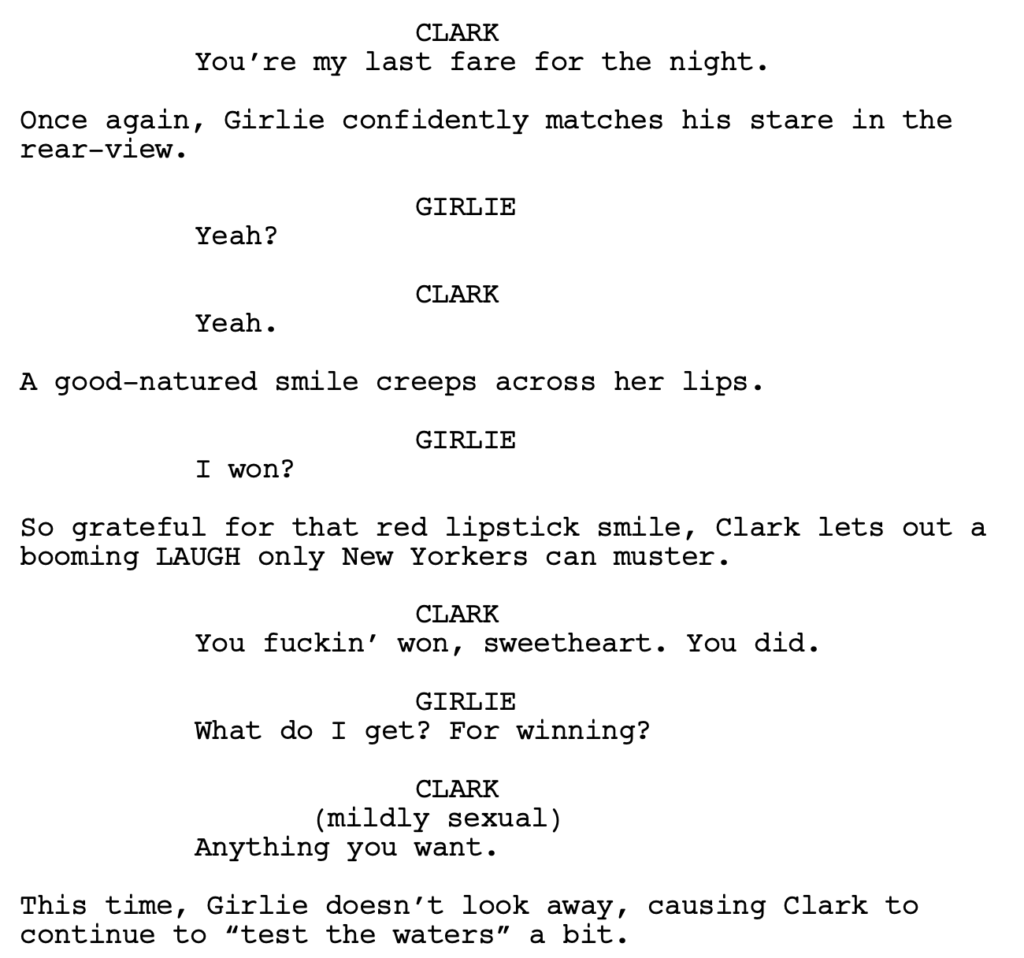

The second segment, however, is where Hall starts to take off. She’s in a triple-7 and everyone else is putt-putting around in a Mini Cooper. Quite frankly, it makes me jealous. Usually, when I read dialogue, I can break down what the writer is thinking and how they crafted the scene to make the dialogue work. But here, there’s so much going on, it’s impossible to keep up.

I like the exaggeration and specificity after the mention of the word “app.” It isn’t just, “These f#$%ing apps are making my life miserable.” It’s, “And now, these f@#%in’ apps, all of ‘em – can get a cab, a coffee, burger, soap, socks, wine, water, Chinese f@#%in’ take out – you can get all that s@#t, and not even reach for your purse, not once, not even for tip.”

Reeling off a number of items drives home the reach of this emerging “app world” Clark hates so much.

From there, the monologue accelerates even more. I’m noticing that in “verbal arena” writing, writers use a lot of metaphors. A metaphor takes an object or action and compares it to something familiar but unrelated. “Charles was a fish out of water.” “Love is a battlefield.” “Life is like a box of chocolates.”

Good writers don’t just use quick familiar metaphors. They take those metaphors and play with them. They extend them (which is why this device is known as an “extended metaphor”). That’s a big part of what’s going on in this scene. Our cabbie character is obsessed with this idea of “the cloud,” and how everything goes up into the cloud. But instead of solely treating the cloud as the technical thing that it is, in this case, it’s used as a metaphor for a real cloud. And what happens when real clouds get full? They start raining.

Hall also intermittently uses something called “personification.” This is when you take a non-human object and you give it human traits. “That big f@#%in’ cloud, thinkin’ it knows better. Swearin’ it can keep a secret.” Then later: “they’re gonna be like f@#%in’ pay phones. Just sittin’ there. Lookin’ dumb. Waitin’. Waitin’ for somebody, anybody to give ‘em a ring. Havin’ no idea… the world’s moved on.”

Another device Hall uses is something I call the “history lesson.” It’s when a character will bust out some historical story or fact that teaches the reader a little something and adds variety to the monologue. We’re in the present and then – BAM – we’re in the far-off past.

“I mean… Salt used to be money. Mother fuckin’ salt. The same shit you sprinkle on your eggs. Yeah. Every mornin’ you toss that cheap-ass-shit all over your eggs with no idea that people used to die for it. Tea, coffee, same thing. All that shit you gloss over at the grocery store, at one point in time, humans fuckin’ killed each other for it.”

This moment in the monologue is important to highlight because I don’t think 99% of writers would’ve written it. Why go off on that tangent when you can be more succinct? But that’s who this character is. He’s a tangent guy. So you want him to go off on a lot of tangents.

Hall then writes my favorite line in the monologue: “Little numbers on a screen. You can’t touch it or hide it or bury it. Nah, you just tie it to a fuckin’ butterfly and send it to that cloud up there.” I have no idea what the device is here or how Hall came up with this line. It seems to be pure imagination, the writer’s own creativity. She could’ve easily written, “You can’t touch it or hide it. It’s just up there in the cloud, hovering.” Not nearly as imaginative.

I like how she also uses adjectives to spruce up, otherwise, bland objects: “But, one of these days, I’m tellin’ ya, that cloud’s gonna open up and it’s gonna pour acid rain down… all over our dumb faces.” It’s not “rain.” “Rain” is way too bland. It’s “acid” rain. It’s not “our faces.” “Our faces” doesn’t tell us much. No, it’s our “dumb” faces.

At every opportunity, Hall is looking to turboboost her sentences. She’s using every pixel to weaponize these words so that they have impact.

From there, she continues to use metaphors to make the dialogue more interesting. “We’re f@#%in’ Blockbuster, you know?” And, “We’re fightin’ it too hard, swimmin’ up stream. Busy swimmin’ and missin’ the whole f@#%in’ boat… Me, too. I been fightin’ it, too. Swimmin’, swimmin’ hard…”

The biggest lesson to take away from today’s dialogue example is metaphors. A lot of the color from this dialogue comes from Hall repeatedly dipping into metaphors. Yes, there’s more going on. But if you try to ingest it all, I’m afraid it will be too much. Just start to look for ways to incorporate more metaphors into your dialogue. Make sure you’re doing so in an organic way. And try to play with them a little bit so they’re not cliched metaphors. You don’t want to say things like, “Flying off the handle” or she has a “heart of gold.” These are actually referred to as “dead metaphors” because they’ve become so overused. Try to come up with your own metaphors and then extend (play with) them.

Here’s the screenplay for Daddio if you want to see more of Christy Hall’s writing. Leave your thoughts about what else she’s doing right in the comments. And, if you disliked the dialogue, tell us why.

GET A SCRIPTSHADOW SCREENPLAY CONSULTATION! – As much as we writers think we can do it alone, we need help. We need fresh eyes on our material. Without that, we can’t identify the problems in our scripts. We won’t figure out where we need to improve as a screenwriter. I’ve read over 10,000 scripts. Done over 1000 consultations. I am the guy who can figure out the issues hampering your script AND HELP YOU FIX THEM! I have a 4 page notes package or a more detailed 8 page option designed to exponentially improve your screenplays. I also give feedback on loglines (just $25!), outlines, synopses, first acts, or any aspect of screenwriting you need help with. This includes Zoom calls discussing anything from talking through your script to getting advice on how to break into the industry. If you’re interested, e-mail me at carsonreeves1@gmail.com and let’s set something up!

Genre: Legal Drama (True Story)

Premise: The life of a cynical San Francisco criminal lawyer at the top of his career unravels when he agrees to represent a father accused of killing his infant son in an extraordinary case that challenges widely accepted medical beliefs, a biased justice system, and his own personal worldview. Based on true events.

About: This is the second script in last year’s Black List that has three writers on it! The first was the script written by the Murder Ink trio, which I liked. These writers have begun to make some minor inroads into the industry. Nathan Gabaeff has a movie he wrote and directed called Avenge the Crows. His brother Isaac wrote a TV episode. But making the Black List appears to be their big break.

Writers: Thomas Berry, Isaac Gabaeff, and Nathan Gabaeff

Details: 121 pages

Carrell for Conlon?

Carrell for Conlon?

If it’s taken me this long to review a Black List script, it typically means there’s something I find questionable about the concept. With False Truth, the concept seems to be both too small and too misguided. Let me explain. The idea is small in that it could be a Good Wife episode. Courtroom thrillers used to be common until legal TV dramas pillaged all their scenarios.

This makes almost every courtroom concept today a TV episode in the audience’s minds. Back in the day, John Grisham was able to find a few big flashy legal cases that felt like movies. But, since then, we’ve had a few thousand television courtroom cases, so it’s super rare to find one that’s worthy of a movie canvas.

The other problem I have is that there’s no winning when the subject matter is a baby’s death. If the father wins the case, so what? His baby doesn’t come back to life. So all of us still lose. Can a concept get more depressing?

I was confused as to why anyone would want to write a movie about this until I got to page 28. That’s when I read this line: “But if it’s a shaken baby case there’s one guy you really want to get… Doctor Steven Gabaeff.” Gabaeff? Where have I seen that name before? It took me a moment but then I realized, wait a minute, this is the writer’s last name!

So, obviously, the writers knew someone – I’m guessing it’s their dad – who was involved in this case and because they have such intimate knowledge accessible to them about the case, they said, “We should write a movie about this.” The fact that the writers did have that connection made me more intrigued. But I still think it’s a tough sell with a concept like this. Let’s see if I’m wrong.

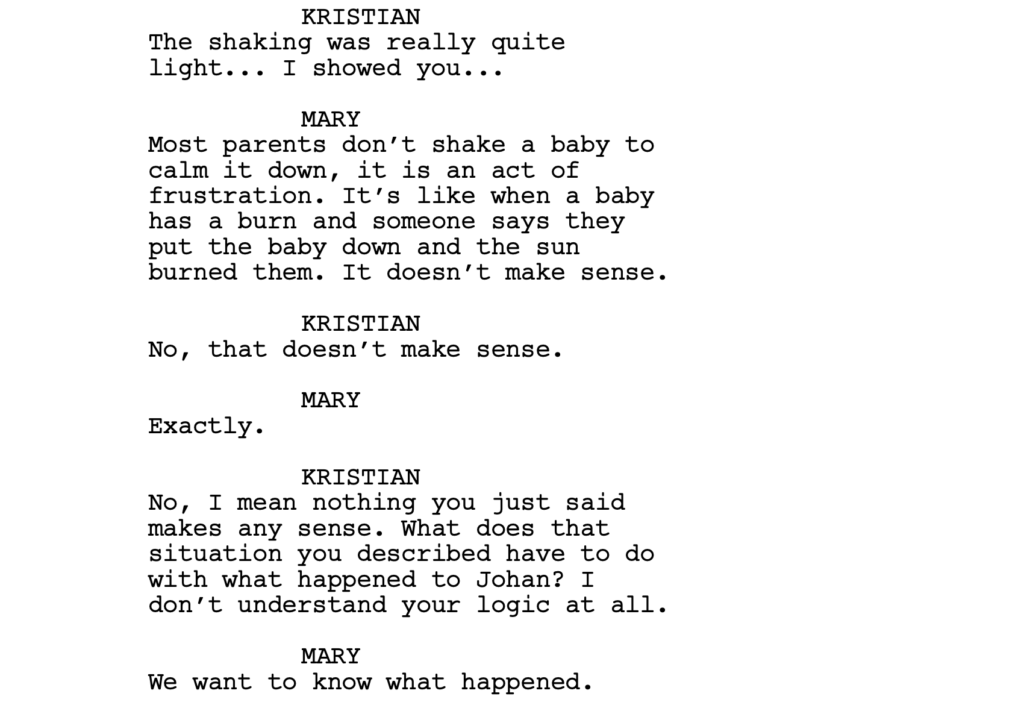

Jennie gets the worst call imaginable from her husband, Kristian, who’s just told her that their infant son is in the hospital because he dropped him. She races to the hospital where she gets updated. Her son is now in a coma (he eventually dies) and the doctors suspect that Kristian has attempted to kill his son with something called “Shaken Baby Syndrome.”

This is when you shake a baby too fast. Kristian is quickly carted off to jail and Jennie hires noted San Francisco attorney Elliot Conlon, a man who used to stand for things but now seems content with making a lot of money, no matter who the defendant is. That’s going to be pushed to the limit since he’s now defending a potential child murderer.

Conlon digs deep into the science of Shaken Baby Syndrome and learns that they have the nastiest lobbyists in the world. These people make sure that every person who gets accused of this spends the rest of their life in prison. Conlon’s also been dealt a bad defendant, as Kristian is big and emotionless. He’s immediately compared to Lennie Small from In Mice and Men.

As we race towards the court case, Conlon finds out that the whole Shaken Baby world is a lie. That the science doesn’t hold water. In fact (spoiler), he learns that the medical community and legal community know this but that they’ve convicted so many people of it by this point that there’s no going back. They have to keep reinforcing the lie. Luckily, Conlon puts enough fear into the establishment that Kristian is inevitably let go.

There are a couple of approaches you can take to a story like this. You can create doubt about the suspect and then take your reader on a roller-coaster ride where sometimes you make the suspect look innocent and sometimes you make them look guilty, and the reader is constantly trying to solve that puzzle.

This is the approach they take in docs (or series) like The Staircase. At first we think the husband definitely did it. Then, when we hear him talk, he doesn’t sound like he did it at all. Then, a little later, we learn that he was having affairs. Now we think he did it again. But then we’re told that the wife knew about the affairs. Then we hear another woman he knew died from a staircase fall and we’re back on the “guilty” train again. These can be fun when executed well.

The other approach you can take is the one they took in this script. Which is that the father is clearly innocent but everyone in the world thinks he’s a child-killer and they’re determined to make sure he’s convicted as so. This creates an enormous amount of sympathy from the reader because nobody wants to see something bad happen to someone who’s clearly innocent. Even less so if everyone wants to take him down in bad faith.

For that reason, the script worked for me, which I was surprised by. I mean, yes, I still think a script like this is a losing proposition cause it’s so depressing. But I was into the stuff where they’re trying to take down Kristian. I wanted him to overcome their full-force attack.

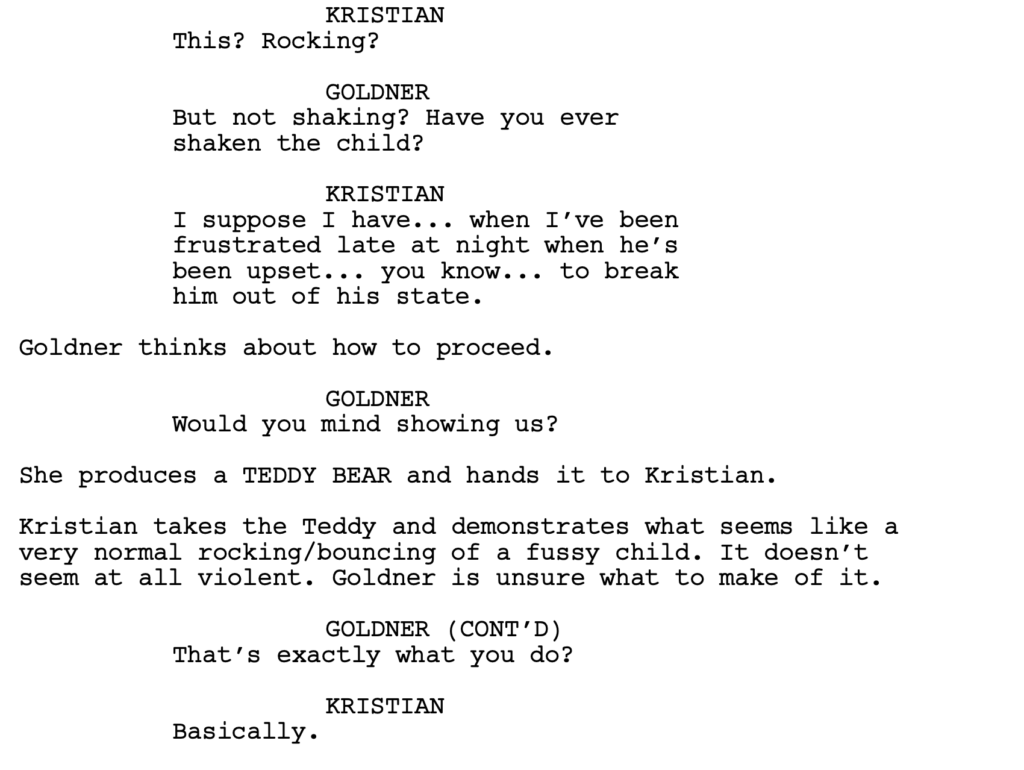

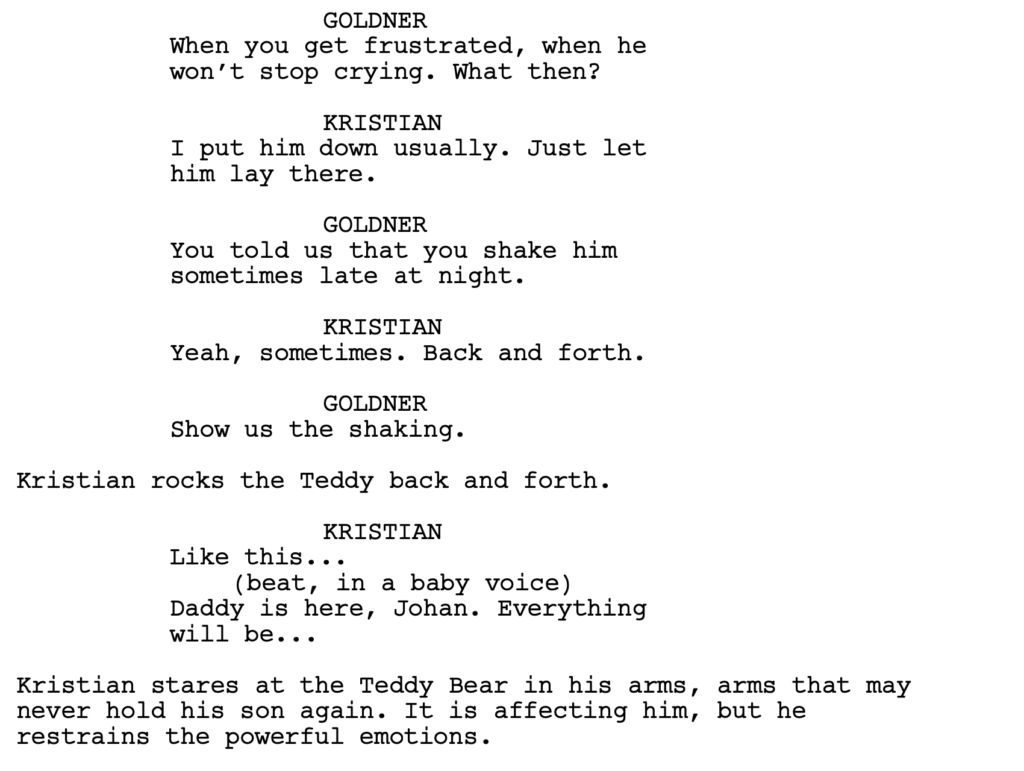

Which is a perfect segue into today’s dialogue lesson. The following scene is a long one. But it’s also a great example of how you can write good dialogue without being a wordsmith. If you’re good at setting up the right scenario, the scenario will do the work for you. I think most of you could write this scene yourselves if it was set up for you. Whereas, with a Tarantino scene, maybe .001% of you could write something similar. In other words dialogue scenes like this are within reach.

The scene takes place with Kristian being brought in to see Child Services not long after he and his comatose child arrive at the hospital.

You want to note a couple of key things here. One, the child services characters have the goal in the scene. It’s to find out what led to the kid’s injury. However, here’s where our nifty dialogue lesson comes into play. The child services people are framing the conversation as if that’s the goal. But what they’re really trying to do is get Kristian to admit he killed his kid.

Dialogue always plays better when there’s something going on on the surface, as well as something that’s going on underneath the surface, which is clearly happening here.

Also, note the extremely high stakes of the scene. If Kristian screws up and says the wrong thing, he doesn’t get a pass. That thing very well could be the smoking gun the prosecution uses to convict him of murder in court. Dialogue is electric when the stakes are high.

Another thing is that the child services people are being disingenuous. They’re trying to trick him – pretending they’re on his side when they’re the exact opposite. What this does is it makes the reader protective of Kristian. We feel like he’s being misled, so we become his ally in the scene. We’re rooting for him to survive.

Finally, note the conflict. Almost every good dialogue scene has some level of conflict in it. And what creates more conflict than one side trying to ruin a guy’s life and the other side hanging on for dear life?

By the way, the reason this doesn’t have to be Tarantino-type dialogue is because the content of the scene is so strong. There are real consequences to this moment. And when that’s the case, you don’t need to prove your verbal jousting skills. Those will actually make the scene worse.

Once you’re able to consistently write a scene like this, you’re going to be okay dialogue-wise. Cause these scenes can really carry a script. Just note that a lot of the work here was done before the scene, not in the scene. Once the scene is set up, the dialogue writes itself.

I’m still not thrilled that the overall feeling I get from this script is one of depression. I like to either feel good at the end of a script or, at the very least, I want it to make me think. With that said, the script surprised me by how much it pulled me in. So I think it’s worth checking out.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[xx] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: It helps in these scripts when the case is about something bigger than just winning the case. While False Truth isn’t making a point about racism or anything gigantic like that, it is about the fact that these “shaking baby” cases are bogus and that evil overly-emotional people have been using their influence to convict a lot of innocent people through pseudo-science. So we do get the sense that the court victory has a bigger effect on the world.

As I continue to work on the Scriptshadow dialogue book, aka the greatest book on dialogue ever written (and it’s not even close), I’ve noticed that when you watch film and TV solely to analyze dialogue, you see things you wouldn’t normally pick up on.

For example, I forgot how plot-centric all the dialogue in Hollywood movies was. I knew it was a lot. But virtually 90% of the dialogue scenes are used to explain where we are in the plot or what needs to happen next. And those scenes are very short. I watched Spiderman: Homecoming again and I think there were five dialogue scenes that were longer than 2 minutes. It was crazy.

Meanwhile, you have television, which, because the plot isn’t as important, and because there’s a lot less urgency, the dialogue scenes end up lasting a lot longer. Now, of course, I always knew this. But I didn’t realize how pronounced it was until I compared movie and TV dialogue so closely.

Needless to say, it’s been illuminating and I can’t wait to share all my findings with you.

In the meantime, we have to entertain ourselves not with movies, since nothing came out this weekend, but TV, which is where all the action is at. Tomorrow night we’ve got the Emmys. Go White Lotus. Cobra Kai just dropped a new season on Netflix. The only person they haven’t brought back yet is Mr. Miagi so maybe he’ll turn up this year. Lord of the Rings apparently didn’t give up after its first two episodes and premiered a third one this weekend. I appreciate that they’re continuing to try. House of the Dragon episode 4 comes out tonight (Sunday)! It’s definitely a TV universe we’re living in.

The Disney Expo also debuted some fresh TV news with a new trailer for the stellar looking, “Willow.” That show is coming out of nowhere and I love it. I’m also a bit confused why Warwick Davis hasn’t aged at all considering he was born in the 20s. They gave us a new Andor trailer, which was accompanied by that cool little Star Wars flute score. And, by golly, we’ve got a new Mandalorian trailer, which was easily the highlight of the expo due to the return of… BABU-FREAKING-FRICK!

Maybe Lucasfilm reads Scriptshadow because I said after Episode 9 that if Baby Yoda and Babu Frick ever met, political division would subside, countries would voluntarily destroy their nuclear arsenals, chupacabras would fly around on unicorns, and there’d be world peace for 500 years. Well, folks, it looks like that’s going to happen cause I saw Baby Yoda in this trailer and I saw Babu Frick in this trailer and since I know that Star Wars would NEVER imply such a divine meeting and not show us said meeting, that wondrous Star Wars moment which we shall all need a week of rest from afterwards in order to recuperate, will happen. And, to me, that’s the only episode they need to air and I’ll be happy. Actually, just air that scene and I’ll be happy. A 90 second season and I’m a Star Wars fan again.

The exact opposite of Baby Yoda Babu Frick cuteness would be the upcoming Andor, whose latest trailer seems determined to frighten away anybody under the age of 55. “Fun” is not in the Sabacc cards for this Star Wars show as our showrunner, the only showrunner in history who openly despises the show he’s making, attempts to give us something so serious, it makes Manchester By The Sea look like Jumanji. I mean, I’m going to watch this show. But every trailer has been woven through a “No Fun For You” app, where as soon as a happy moment is detected, it is destroyed with extreme prejudice. I think people *think* they want a serious Star Wars show. But they may be surprised at what Star Wars looks like without fun.

Another big announcement was the Marvel “Secret Invasion” trailer which is a quasi sequel to Captain Marvel and follows Samuel Jackson’s Nick Fury as he navigates an alien invasion that’s secretly happening under mankind’s nose. This was originally supposed to be a movie and the fact that they turned it into a TV show tells me that Marvel isn’t so hot on giving Nick Fury his own movie. Which they probably shouldn’t. I’m surprised they’ve gotten as much mileage out of the character as they have. But, in his current state, they may as well nickname him, “Nick Furgettable.” At least the show has Ben Mendelsohn. He’ll be fun. But I think the only invasion that’s going to happen with this show is of the low ratings variety.

D23 did have some film news. Unfortunately, they didn’t show as anything we really wanted to see, like the Indiana Jones 5 trailer or the Avatar footage (is anyone as confused as I am that Avatar 2 is coming out in December and all we’ve seen is a teaser?). I know that everyone was highly expecting the Fantastic Four cast to be announced but I get the sense that Feige wants to take his time with FF4 because nobody’s ever been able to figure it out. I mean, the last version of it had four of the hottest young actors in Hollywood at the time, along with one of the buzziest directors. And it turned into a disaster. So there’s something about this franchise that isn’t easy to crack. And kudos to Feige for taking his time and figuring it out.

We got to see the Little Mermaid trailer, finally. It honestly looks better than I thought it was going to. This is easily the most difficult “live-action” adaptation Disney has done of its animated classics. I’m not bothered by them changing Ariel’s ethnicity. The spirt of the character seems to have been captured and that’s what’s most important. I do think it’s weird that these live-action movies are all animated though. You’re animating your animated movies. Like, whoa, dude. Do we even live in life anymore?

The most surprising announcement was the lineup for the Marvel Thunderbolts movie. For those who don’t know, Thunderbolts is Marvel’s answer to The Suicide Squad. They’re the bad guys who are going to come together and be good for a little bit. The team is being led by the new Black Widow, played by Florence Pugh, which I think is a great choice. It’s got her brother, Red Guardian, played by David Harbour, another character I like. From there, things get wonky.

You’ve got Taskmaster, who was a fairly cool character from Black Widow with some neat fighting scenes. You’ve got Winter Soldier, who continues to be one of the most uninteresting superheroes ever. I don’t know why he continues to show up in the Marvel universe. You’ve got Ghost, who was that awful villain from Ant-Man 2. The real team-up in that movie was her and Wasp. Unfortunately, their goal was to destroy the Ant-Man franchise. Then you have US Agent, who I don’t even understand. I guess he’s a Captain America knock-off?

As you can see, the movie doesn’t have a stand-out superhero. Its best character is probably Black Widow 2 and she’s barely had any time in the Marvel Universe. So it’s asking a lot for her to lead the charge. It’s not too late to add some star power, Mr. Feige. I’d like to see Venom in there. I’d love to see Deadpool. Gimme some Wolverine. Grey Hulk. Daredevil. Moon Knight. In other words, some characters who could actually add legitimacy to the franchise. This all feels very “B-Team” at the moment.

Finally, the Oscar season is beginning, which means you’re going to start seeing big campaigns pop up and hear things like, “The film that got a four-hour standing ovation at the Icelandic Film Festival.” It can be hard to see through the marketing fog. But I’d personally look out for The Whale and The Menu, two scripts I loved. Steven Spielberg’s autobiographical movie, The Fabelmans, seems to have had a nice debut at Toronto. There’s another Knives Out movie for Star Wars destroyer, Rian Johnson, which I’m sure some will enjoy. And there’s the star-powered Babylon, from La La Land director, Damien Chazelle. We’re going to be seeing all those movies as the year wraps up. By the way, every one of those films is going to be dialogue-friendly.

Which reminds me, the hardest thing about dialogue – and something I’ve seen you guys discussing in the comments – is the aspect I’m tentatively titling, “the verbal arena.” It’s that aspect of dialogue that feels unteachable. It’s Fleabag’s unique take on late night hook-ups. It’s Juno’s colorful vocabulary. It’s Pulp Fiction’s roundabout playfullness. It’s where creative dialogue really comes from. I’m curious what you guys think is the secret to “the verbal arena.” Is there a way, in your opinion, to learn that? If so, what are your methods for doing so?

Spoiler alert: I think everyone can get better at it. But I’m curious to hear what you guys think.

I’ve been working hard on my dialogue book.

One of the most frustrating things about writing the book has been finding recent movies with good dialogue to reference! Most great feature film dialogue went out the window in the early 2000s with the death of the indie film. If any of you have suggestions for good dialogue movies post-2015, I’d love to hear them in the comments.

For this reason, I decided to go in the opposite direction and throw in one of the most famous dialogue movies of all time and one I’m not intimately familiar with – Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf. I think I even did an article about this movie years ago but I don’t remember a lot from the film other than the characters all seemed very angry.

Rewatching it was strange because I’ve been writing all of these dialogue tips in my book, believing they were inarguable, only to realize after Virginia Woolf, that there’s more to this dialogue thing than meets the eye.

A rule I was absolutely certain of was that, going into a scene, at least one character needed to have a goal. I didn’t think dialogue could survive without that. Because, otherwise, people are just talking to fill in the space. There’s no purpose to what they’re saying.

Well, with Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf, which is about an aging couple who works at a prestigious university and a young couple who come by for some late-night socializing – I realized that this divine dialogue truth wasn’t as universal as I thought.

The characters here would often speak without a clear goal, and for long periods of time. In fact, there were even moments where characters only spoke to break the silence. I mean I guess you can say that “breaking the silence” is a goal, so maybe my precious rule is still in tact. But I didn’t think that a scene could survive when the goal was that weak.

As I continued to watch the movie, I realized that there was one dialogue truth that is always present – and that is CONFLICT.

This whole movie is slathered in conflict. There isn’t a single frame that doesn’t have it. So even though the characters are not always speaking with purpose, the dialogue is still entertaining due to the fact that conflict is present.

And it’s conflict on multiple levels, which I think is the reason it’s able to be so good in spite of its lack of clear goals. If you’re doubling up on conflict, that extra dose could be the substitute you need for a goal-less scene.

What do you mean “doubling up,” Carson?

For starters, the central married couple, Martha and George, hate each other. She hates him because he’s not enough of a man (by the way, this is the first fictional story I know of that implores the insult, “Simp”). And he hates her because she’s constantly cruel to him (not to mention, her college president father’s superior presence always hangs over him).

This creates the undercurrent of tension in every scene. It is, what most people refer to as, “subtext.” Even without saying anything, they’re already saying stuff.

Then this young couple comes along with their perfect young bodies and whole life in front of them and it just sets George off. He uses them, then, to spit out various levels of provocation and frustration. That’s where the second level of conflict is occurring – on the surface.

This doubling down ensures that every line of dialogue has bite to it. Here’s a scene from early on in the movie where Nick, the young professor, is starting to get prickly in response to George’s aggression…

I think the issue I’m grappling with here is that while there isn’t an obvious purpose to George’s interaction with Nick – George is not, for example, trying to get Nick to invest in a business venture of his – I’m wondering if there’s some directive to this conversation that can be quantified, and therefore taught.

George is obviously riling Nick up. That is his internal “goal” in the moment. But why? And is it something that I should be teaching writers to do? Have their characters start sh@# with other characters for no reason. Yes, you get conflict-heavy dialogue. But it’s without structure, without a point.

I think that Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf pushes up against that older belief that movie dialogue should mirror real-life dialogue. In real life, people are mean to other people because they hate themselves or hate their life and they’re just stirring the pot to stir it. They don’t have some divine goal in the moment other than to spew out their thoughts and hurt someone else.

Even as I’m writing that, I go back to this idea of: well, maybe all good dialogue does have a goal, then. Because isn’t trying to hurt someone with your words a goal?

In digging a little deeper, I noticed that while there isn’t some big goal George is trying to achieve, he is a LEADER. He is pushing the scene forward. And that’s worth bringing attention to. Because maybe the real baseline to good dialogue is that someone is pushing the scene forward. George is a force here. He is trying to agitate and aggravate Nick. We’re then curious to see if Nick will crack or fight back. Maybe that’s enough.

What you don’t want in a scene is two characters who are passive. The only thing worse than one character who tries to stir sh#@ up for no reason is zero characters who try to stir sh@# up for no reason because then the scene is lifeless.

Another complication to figuring out this odd movie is that it was originally a play. In plays, you have to fill up 90 minutes of talking somehow. Movies are more visual, which allows you to do more showing than telling. So is this just a case of a playwright filling up space with dialogue cause he has to? Dialogue that wouldn’t normally be in a movie?

I’m going to keep working on this because it’s my belief that the best dialogue has purpose. And that purpose comes from a character who has some sort of goal or “want” in the scene. I may have to dig deeper into Virginia Woolf to see if the film is, indeed, achieving this and I’m just missing it, or if there are deeper secrets yet for me to learn about dialogue.

In the meantime, feel free to provide your own thoughts on this movie, your own suggestions on good dialogue movies post-2015 from screenwriters not named Tarantino (I’ve got enough of him in the book). Share your own dialogue tips. And leave suggestions on what aspects of dialogue you want explored in the book. Feel free to share your dialogue struggles as well. The more I know about what perplexes you guys, the better I can make the book.

Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf is on HBO Max.

$50 OFF A SCRIPTSHADOW SCREENPLAY CONSULTATION! – The Labor Day deal may be over but you can still save some money on a script consultation! I have a 4 page notes package or a more detailed 8 page option designed to both fix your script and improve your writing. I also give feedback on loglines (just $25!), outlines, synopses, first acts, or any aspect of screenwriting you need help with. This includes Zoom calls discussing anything from talking through your script to getting advice on how to break into the industry. If you’re interested, e-mail me at carsonreeves1@gmail.com and let’s set something up!