Search Results for: F word

Genre: Drama

Premise: Awkward and lonely, Jared is only able to find a community online — until the day he realizes that his favorite Youtuber lives nearby. Desperate for a connection, he becomes determined to find a way into her life… whether she wants it or not.

About: This script finished with 7 votes on last year’s Black List. The writer, Alexandra Serio, has written and directed a couple of short films, one of which looks to be the inspiration for this screenplay.

Writer: Alexandra Serio

Details: 90 pages

One of the things I’ve been actively doing over the past month is weening myself off junk food internet content.

I’m doing this because, ironically, I watched a Youtube video about the effects of social media and what the video noted was that, a hundred years ago, you read the news in your small town and were immediately able to do something about it.

For example, if the local church burned down, you’d be able to get together with the community and help rebuild it. You’d have a physical outlet for the unresolved news issue.

But today, the news is always so far away – “Crazy Thing Happens in Washington!” – that you can’t actually do anything about it. So the energy that the news generates inside of you stays put, along with all the other junk you come across on the internet, creating a ton of anxiety that comes out in unproductive ways.

I bring this up because, as I’ve been detoxing, I’ve spotted more and more of these “black pill” videos. Since I don’t click on them, I don’t know much about the black pill philosophy. But from my understanding, it’s a negative defeatist way for men to look at the world.

Naturally, then, it’s a perfect backdrop for a screenplay! So let’s get into it!

Jared is in his 20s, lives in a trailer with his mom, and works at Wal-Mart. So, yeah, things aren’t going well for Jared. Jared deals with this through the “black pill” online community. Essentially, black pillers believe that certain men, aka “incels,” will always be invisible to women and therefore they should either accept this and not try to get with women or kill themselves.

But a tiny part of Jared is holding out hope. He watches this ASMR influencer online and she routinely puts out affirmation content where she whispers into your ears as you fall asleep that you are “worthy” and that “looks don’t matter.” Stuff like that.

Lo and behold, Jared can’t fathom his luck when he spots Dee AT HIS WAL-MART! As a Black Piller he can’t actually go up and talk to her so he follows her from a distance, even leaving work to follow her home. Once she’s home, he’s able to watch her livestream in person. As in stalking from his car across the street looking through her window “in person.”

When Jared sends her the livestream question, “Do you have a boyfriend?” And she ignores it, he goes ballistic. A primal incel force is triggered inside of him. He goes and buys a bunch of home improvement stuff and renovates an abandoned trailer near his home. He then sneaks into Dee’s home, waits for her, and kidnaps her (while wearing a mask) during her livestream!

He chains her up in his secondary trailer and starts reading all the news. Due to being kidnapped on a live stream, Dee becomes a national story. Jared spends the next couple of days not really sure what to do with Dee. He’s like the cat who finally catches the laser beam. Now what? He ultimately decides to execute a dramatic suicide on Dee’s channel. Will he be able to pull it off?

As you guys know, I love a good character description.

They’re an easy way for me to identify if I’m reading a good writer.

I really liked the description of Jared here. It’s a little long. But the main thing with any character description is that the reader HAS A GREAT FEEL FOR THE CHARACTER after they read it. So here’s Jared’s description in Blackpill.

JARED, a weary 20-something, enters and drops into a gaming chair exhausted. One look into his dark eyes reveals his exhaustion is soul deep; the look of a man who truly believes he’s never caught a break.

Let’s break this down piece by piece. First we get his age with the added bonus of an adjective. Right away, we’re learning things about this guy.

We’re then told he drops into a “gaming chair.” A “gaming chair” is a very specific piece of furniture. That’s what you want to do as a screenwriter. You want to focus on the SPECIFIC things your character has. Not the general things. If you would’ve told us that Jared, instead, dropped down onto “a couch,” that doesn’t give us nearly as much information about him.

The next sentence gave me even more insight into Jared: “One look into his dark eyes reveals his exhaustion is soul deep.” That’s a different situation than someone who’s simply “exhausted.” “Soul deep” means the exhaustion is irreversible.

Finally, we get this tag about how he “believes he’s never caught a break.” I love that description because we all know people like this, people who believe that life is against them and is determined to make their existence miserable, and how they use that as a sort of defense mechanism to explain not trying to improve. In 40 words, I have a great feel for this character.

Contrast this with yesterday’s character intros. Here’s one for the sister from that script, Brie:

SNIFF! BRIE MORGAN (38, pretty like a wilting flower) snorts a bump of blow like a pro.

The one good thing about this description is that we’re introducing the character during an ACTION, and actions are a great way to tell us about a character. The problem is that snorting coke is one of the most cliche actions in movies. Contrast this with the gaming chair. The gaming chair is SPECIFIC. Snorting coke is GENERIC.

We’re then told, rather clumsily in parenthesis, that Brie is “pretty like a wilting flower.” What does that mean? Is a wilting flower still pretty? So you’re saying she’s kind of pretty? Or are you saying a wilting flower isn’t pretty at all and therefore she’s ugly? Trying to be too clever by half when you’re not clever in the first place is a recipe for writing disaster. Clarity over cuteness, always.

Or here’s one from a script I’m going to review in the newsletter:

Subtle pockmarked scars surround sage eyes — eyes carrying oceans of weight. In another life he may have been a poet.

Holy Moses is this weak. Eyes carrying “oceans of weight.” Extremely clunky phrasing that doesn’t quite make sense. Avoid at all costs. “In another life he may have been a poet.” That’s a strange thing to say after the “oceans of weight” debacle. Where is the connection? Just because you have a lot of history in your eyes, you’re a poet all of a sudden? Weird description all around.

Just remember that when it comes to descriptions, the harder you try, the worse you do. Key in on your hero’s defining characteristic (like Jared, he’s almost given up on life) and give us a simple description that conveys that.

As for the rest of Blackpill, it was pretty good. I enjoy the sub-genre of characters in mental decline. There’s a built-in trainwreck aspect to the narrative and as much as we hate ourselves for it, we all look forward to seeing the crash when we pass it. One of the best versions of this sub-genre is Magazine Dreams. Very similar to this script.

Where I had some issues with Blackpill was with the plot. There wasn’t a whole lot going on in it. Man feels unseen. Man sees influencer he’s obsessed with. Man prepares to kidnap influencer. Man does kidnap influencer. Man executes plan to kill himself.

My issue here is that I couldn’t figure out which route the writer wanted to go down. If this was a stalker thriller in the vein of Single White Female, it needs more twists and turns. If it’s a character study like Joker, you need to dig into the character more. Or, in this case, into both characters. While I had a good feel for Jared, I didn’t know Dee that well. And in a narrative this simple, you probably need to expand the character work to include the co-star.

Cause I think that’s what would’ve elevated this. Let’s look at the circumstances by which a guy could be pulled into this dangerous online religion. But let’s also see how girls can be pulled into, arguably, the just as dangerous religion of influencing. I felt like Serio was starting to go there towards the end. But it was too little too late. I believe this becomes a much more intellectual experience if we’re showing Dee’s influencer obsession as well.

With that said, it’s an easy read and I wanted to find out how things were going to end. As long as you accomplish that, you’ve written a good script.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: This script is a great example of how point-of-view changes a story. If you write this from Dee’s point of view, it’s a survival story. If you write this from Jared’s point-of-view, it’s an obsessive stalker story. But there’s a third option. You can write it from both points-of-view. And then it becomes more of an intellectual experience, something that gets cinephiles and critics talking. So always explore every potential point-of-view before you write your script. You might be overlooking the best version of your screenplay.

If you can write a character like Mikey, in “Red Rocket,” you’re in the discussion!

If you can write a character like Mikey, in “Red Rocket,” you’re in the discussion!

So, recently, a producer came to me saying he had a project he was trying to put together and needed a writer for it. This wasn’t some giant producer. But it was someone who could pay a writer real money. He hadn’t had a lot of success with literary agents, who he found pushed their weaker writers on him since he wasn’t A-List. Which is why he came to me. He knew I’d read more amateur screenwriters than probably anyone in town so, he figured, if there’s anyone who can find me a writer, it’d be Carson.

I get inquiries like this every couple of months and whenever I do, it helps me zone in on what it is that actually makes a good screenwriter. Because when you’re talking about screenwriters theoretically, there’s a leniency in your judgement. I want every screenwriter to succeed, especially the screenwriters on this site. So I see them through the lens of optimism and potential as opposed to reality.

But when someone’s paying money, all of that goes away. The last thing I want to do is refer a writer to someone, have that someone pay them a big check, only for the writer to deliver a weak script. Cause, of course, then I look bad.

So, all of a sudden, my eye becomes more astute. I’m able to see exactly what makes a screenwriter worthy of being a paid professional as I am literally recommending them to be paid. What is it I notice that prevents me from recommending someone and what is it I notice that leads to me endorsing them? That’s what I want to talk about today.

The first thing I notice is that the pool of writers I’d recommend to a producer is very small. We’re talking .5% of all the amateur writers I’ve read. Now before you freak out about that number, you have to understand that I’m not talking about recommending a writer to an agent here, of which the bar is more in the 3-5% range. I’m talking about actual money being transferred into the writer’s bank account. That’s a different conversation.

It’s the difference between potential and someone who’s got the goods. There are actually a handful of EXTREMELY TALENTED but raw screenwriters I know who I’d never recommend for this job because, to do this job, you have to understand the *craft* of screenwriting. You have to understand what the producer wants and have an actual game plan for putting it on the page.

These super-talented writers may have strong voices or a knack for great dialogue or a talent for taking stories to unexpected places. But many of those talents are connected to the freedom of constructing their own narrative. That approach doesn’t work as well when you’re adapting someone else’s idea.

To do that, you really need to understand structure. This is where the debate on whether there’s a “right” or a “wrong” way to write a screenplay leans towards “there is a right way.” Because the majority of Hollywood operates in the 3-Act Structure. Act 1, Act 2, Act 3. A beginning, a middle, an end. Setup, conflict, resolution. 25 pages, 50 pages, 25 pages. If you don’t understand that, it’s very hard to have a common language with your employer.

So that’s one of the first things I look for. I say to myself, “Do they understand the 3-Act Structure?” Cause if they don’t, it doesn’t matter what else the writer is good at, the script isn’t going to be paced well. It won’t have direction. It’ll feel like it’s wandering a lot. You got to have structure down, which, by the way, takes most writers about six scripts to feel comfortable with.

The next thing I think about is character. Specifically, have I read characters from this writer THAT I REMEMBER. Characters who jump off the page. Most screenplays – to be fair, even a lot of professional ones – give you characters who work for the story. But those characters don’t stick out. In other words, if you took the story away and just put that character in a bunch of random scenes, would they stick out? Would they be memorable?

For the majority of writers, the answer is no. They haven’t figured out how to do this yet. What do I mean by “memorable” character? Any character who feels larger than life via their charm, their pain, their eccentricities, their personality, their presence. Arthur Fleck, Louis Bloom, Cassandra in Promising Young Woman, Thor, Mad Max, Mikey in Red Rocket (guy in Ferris wheel at the top of this post), Mildred in Three Billboards. These are characters who rise above the page.

If you can pull these two things off, you are in the running. Cause these are the two most important things when it comes to nailing an assignment.

Dangling just below these two is dialogue. I’m not so much a “dialogue has to be great” guy as I am a “dialogue has to be good” guy. The reason for that is, great dialogue is rare. Name me three movies with great dialogue from last year. You probably can’t. Also, ironically, the better the dialogue is, the more subjective it becomes. That’s because flashier dialogue has more personality, and whenever personality is involved, some people hate that personality and some love it. Look no further than Juno’s dialogue as an example.

So I’m looking for dialogue that’s solid. There’s an honesty to it. There’s an effortlessness when it comes to covering exposition. The writer understands what dramatic irony is. They understand what subtext means. They also have the ability to add some extra flair to the dialogue to make it sound heightened, without it feeling try-hard.

If you can do those three things well – structure, character, dialogue – you are very much on my radar. I am now considering you for a paying job. Because now I know, at the very least, you are going to deliver a competent draft.

So, we’ve shrunk our pool of writers down to a small group. Who gets the job out of the remaining scribes?

Before I give you the general answer, I’ll give you the real-life one, which is that it depends on the project. If the project is dialogue heavy, I’ll go with the writer who writes the best dialogue. If it’s a comedy project, I’ll go with the funniest writer. If it’s a project that requires a certain weirdness, like The Lighthouse, then I’m recommending the writer with the most offbeat voice.

But if it’s a more generalized project, like, say, a biopic, I’m simply going with the best writer, or the writer I think has the most talent. Not only are they able to do all the things I listed above, but they also have that rare x-factor where they’re able to construct fictional stories in fresh and unexpected ways that make you feel things that you don’t feel when you’re reading everything else.

Another way to look at it is, somebody who’s the opposite of the average writer. The average screenwriter – someone who’s studied the craft and written more than six screenplays – does everything well, but nothing exceptionally.

If you want to become a paid screenwriter, you have to do at least one thing exceptionally. It can be that you write memorable characters, it can be that you write great dialogue, it can be that you’re so locked into the human condition that you can turn the average moviegoer into a slobbering pile of tears. But it’s gotta be something.

And part of the process of becoming a professional writer is identifying not necessarily what you *want* to be good at, but what you *are* good at, then writing scripts that allow you to showcase that talent. And then writing more of those scripts. And then writing more of them. Until you become an expert in that one specific area of writing. Because that means that when that type of project comes around, producers are going to think of you.

Finally, being the best at any aspect of writing is really hard. So there’s another option. Create your own future. After watching Tangerine this week (shot on an iPhone) and Cha Cha Real Smooth (made by a 22 year old), I’m reminded that sometimes it’s better to bring your own stuff to life than wait for someone else to anoint you. Because, do I think that Tangerine or Cha Cha Real Smooth would’ve lit the screenwriting world on fire? No, I don’t. Tangerine might’ve made The Black List. But Cha Cha Real Smooth wouldn’t have. So if those two were waiting for someone like me to say, “You’re the best of 10,000 writers,” they’d still be waiting. They went out and put those pages on the screen.

The point is, you have options. If nobody else believes in you, you can still succeed by believing in yourself. Whatever route you take, make sure to give it everything you’ve got. Cause I promise you, the competition is too stiff for any other approach.

Happy writing this weekend!

$100 OFF DEAL! – I’m giving $100 off two feature screenplay consultations this weekend. E-mail me at carsonreeves1@gmail.com with subject line: “100.” I give screenwriting consultations for every step of the process, whether it be loglines, e-mail queries, plot summaries, outlines, Zoom brainstorming sessions, first pages, first acts, pilots, features. If you’re wondering where your structure, or characters, or dialogue, stand, you can ask me to focus on them in your notes and I’ll be happy to assess them. E-mail me and let’s set something up!

Genre: Sci-Fi

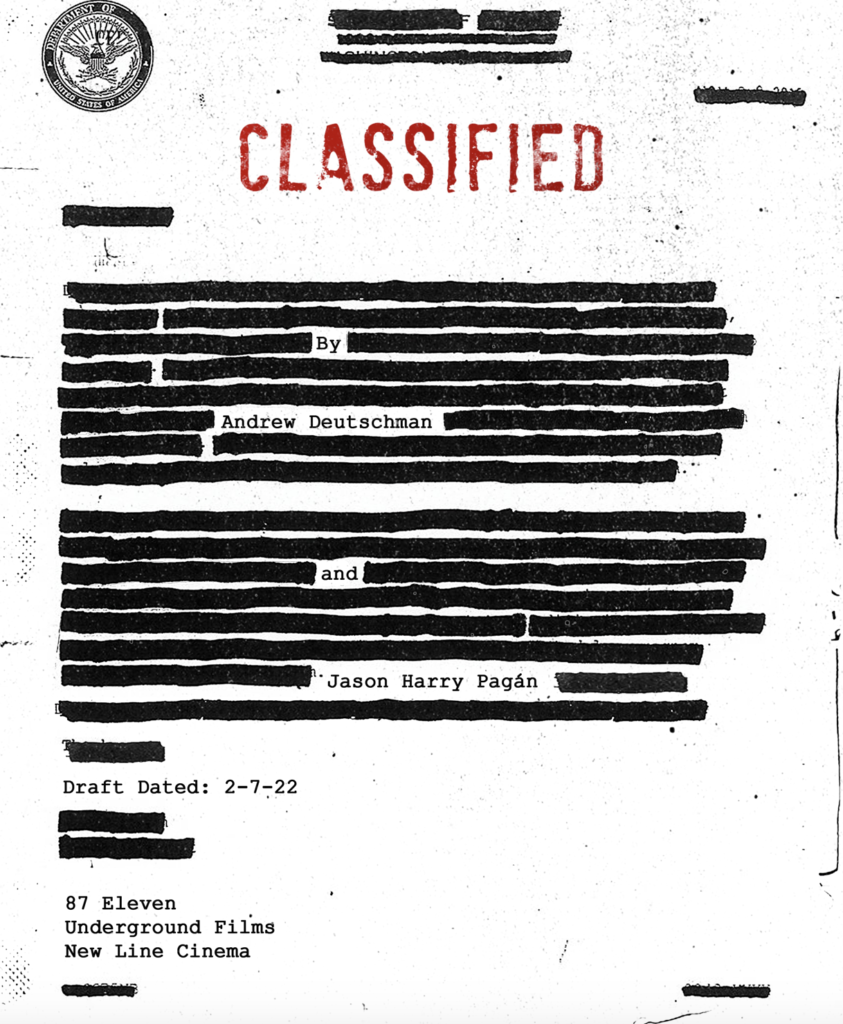

Premise: A mysterious terrorist takes over a top secret U.S. mountain military base that contains within it every ancient artifact that the U.S. has ever collected.

About: New Line just won the auction for this project. John Wick 4 helmer Chad Stahelski will direct it. The writers are Andrew Deutschman and Jason Pagan, who are on a tear right now. They just sold a horror project to Neal Moritz based on a series of TikTok videos, another horror project to Netflix, and a third horror project to eOne with one of my favorite directors, Andre Ovredal (Trollhunter), set to direct.

Writer: Andrew Deutschman and Jason Pagan

Details: 114 pages

Today’s script makes me want to think of potential movie crossover pitches that would blow a studio executive out of the water.

The Matrix meets Shutter Island.

Star Wars meets The Joker.

Jurassic Park meets Deadpool.

Alien meets American Psycho.

Okay, fine. Those all suck. But today’s crossover does not suck. Die Hard meets Raiders of the Lost Ark?? Every 80s kid just got the visual material required for their next 30 wet dreams.

But here’s the funny thing with these monster crossover ideas: they can become a victim of their own amazingness. The reader is going in SO EXCITED that how can what’s delivered possibly live up to expectations?

We’ve had a few of those scripts come here only to plunge off a cliff. But I’m willing to bet that “Classified” will be different. Grab your whips, check your rear view mirror for stray boulders, and take a trip with me into this booby-trapped screenplay cave! And watch out for snakes!

Cold open on the Cold War era, circa 1956. American Captain Carl Stoller escapes a laboratory right before a black sickness overtakes everyone inside. This disease came out of an ancient box scientists were studying.

Cut to present day and black market dealer Charlie finishes selling stolen ancient swords and vases for hundreds of thousands of dollars. As he’s packing up, Hamid Al-Ahtari arrives and tries to tell him a shield he claims belonged to Achilles. Yes, of heel fame. Charlie is incredulous but when a mysterious 90 year old man (Mr. X) backs Al-Ahtari up, Charlie gets the feeling the shield is the real deal.

But the second he buys it, the FBI charges in, led by Agent Jordan Gelman (a woman), and a kerfuffle follows. Charlie and Jordan end up on a Harley chasing Mr. X and Al-Ahtari in their truck, a truck that eventually crashes into a fuel tank, exploding! But somehow, there are no bodies inside the wreckage. Only the Achilles shield!

A couple of months later, Mr. X and Al-Ahtari break into a secret missile Silo base inside a mountain. That base happens to have a collection of Raiders of the Lost Ark like boxes in the back, things the U.S. military has collected over the past century. And guess what? They’re going to steal all of them.

It’ll be up to Jordan to lead a team in there (through a back tunnel connected via Camp David, the president’s vacation home) and stop Mr. X – who, by the way, sheds his old man skin revealing a 30 year old Carl Stoller! Jordan will need the help of the guy she hates most in the world, Charlie, to figure out what these guys plan to do with these artifacts!

Once the pair lead a team of agents into the mountain base, they realize what it is Stoller is looking for. PANDORA’S BOX. That’s right, the biggest artifact of them all, even bigger than the Ark of the Covenant! Since everyone’s aware that once Pandora’s Box is opened, it can never be closed again, the race is on to stop Stoller before her finds it.

I’m going to talk about something that’s a little uncomfortable but if we’re being real with ourselves as screenwriters, it’s an important conversation to have.

What is your level as a writer?

Are you a wordsmith on par with the genius of Cormac McCarthy?

Or are you more on par with the guys who wrote Sonic The Hedgehog?

To be clear, both writers can make money in the writing space. But you need to know which one you’re closer to as that will determine what kind of scripts you should write.

Put simply, the lower your writing ability is, the more high concept your ideas need to be.

If you’re an average writer, this is the exact kind of script you want to write. Cause any average writer who studies the heck out of the craft and writes a bunch of scripts to get their skill level up, can work in this industry if they’re writing concepts like this one. These popcorn blockbuster type concepts are very forgiving. They don’t need you to be a great dialogue writer or a thematic mastermind. They just need you to write fun characters, fun scenes, and keep moving the story along.

From there, the script will be elevated by imagination and research. You have to be someone with an active enough imagination to come up with memorable scenes, such as being dropped in a 2000 year old snake-infested Egyptian tomb. And you need to do a ton of research to find the cool antiquities that are going to make a script like this shine.

Which leads me to the script’s biggest strength – and I don’t know if I’ve ever celebrated this as a script’s number one quality before – the exposition!

Exposition, Carson?? The script is good because of exposition??

This script is chock full of so much fun exposition about secret societies and ancient cultures and exotic trinkets and fantastical history that every time someone started talking, I found myself smiling and leaning in, trying to “hear” them better.

“In Doha they were in possession of a shield that supposedly belonged to Achilles, the greek warrior. It and had originally been acquired by the CIA in the 50s, when Stoller was a Marine… The shield casts a 30 foot wide radius of complete protection, so much so that if you stood ten feet to the left, and I fired a grenade at you, you wouldn’t even feel a flutter.”

This is where research and imagination collide. As the writer, you have to do the hard work and read the history that gives you your ideas. And I’m not talking about wikipedia pages. I’m talking about books. I’m talking about hardcore hard to find microfilm level sh*t. And you have to read through all the boring stuff to get to the good stuff. Which takes time. Which is why no one does it.

But if you’re not Sorkin, if you’re not Tarantino, this is how you make up for it. Cause you need to give the reader SOMETHING they don’t get anywhere else. Let me repeat that because I don’t think screenwriters understand how important that is: If you’re not giving the reader something no other writer can, then why would they care about your screenplay? So if you can’t offer genius dialogue or effortlessly compelling drama, it’s gotta be something else.

For Classified, it’s the gobs of really fun exposition highlighting all this bonkers mythology.

Another thing I have to give these guys is that they actually NAILED “Die Hard meets Raiders of the Lost Ark.” Sometimes writers use juicy movie crossovers to hype up their script and you read the script and isn’t a representation of the movies at all.

But Die Hard meets Raiders is actually the BEST way to pitch this script. You have a bad guy who takes over a base (aka a building). And you have tons of magical religious artifacts being kept in that building that the bad guys start using (Raiders) and the good guys have to stop.

What’s impressive about this is that I’ve been hearing “What if…” pitches about those boxes at the end of Raiders for decades. Everyone has tried to figure out a way to build a movie around them. The problem is the same problem everyone runs into when they deal with mystery boxes. The boxes are almost always more interesting closed than they are open.

You got to do a lot of research to come up with even one interesting artifact inside a box. And these guys did a good job of making everything that was found fun. I mean at one point we even explore Korean myth Hong-Gil-Dong, Doppelgängers made out of straw that follow their master.

I’m not sure the script ever elevates beyond pure fun. But it sure understands fun. Which is why I had such a good time with it.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[xx] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: This script is a great example of the writers asking themselves, “If someone heard this movie idea, what would they want in the movie?” And then they made sure to give you that. Too many times we come up with ideas and we sort of let them get away from us. Never let your script go so off course that you’re no longer giving the moviegoer the best things about the idea. It’s like if you wrote a movie called Wedding Crashers and the protagonists only crashed one wedding. Audiences are going to be disappointed. Top Gun Maverick is a great example of a film that lived by this mantra. They knew exactly what their audience wanted and gave it to them.

If you would’ve told me two months ago that not only would I *like* Ms. Marvel more than Obi-Wan, but that the show would be infinitely better than the latest Star Wars offering, I would’ve told you’d certifiably lost your mind.

And yet here we are. I have watched 5 episodes of Obi-Wan and 2 episodes of Miss Marvel. And Miss Marvel is executed better in every conceivable way. Today I want to discuss the screenwriting reasons for why that is so that you, dear writer, make more Ms. Marvels, and less Obi-Wans.

Let’s start with the concepts for each show because each is utilizing a time-honored trope, which means there isn’t any originality in the concept of either show. Obi-Wan utilizes the “Taken” trope – a young girl has been taken and he must save her. Ms. Marvel utilizes a “being unpopular in high school” trope.

If you haven’t seen Ms. Marvel, a young high school girl who idolizes superheroes finds an old bracelet in the family attic that gives her superpowers. So while she’s the world’s biggest dork at school, she secretly becomes a superhero herself.

Why does Ms. Marvel’s cliched setup work and Obi-Wan’s doesn’t? Well, with Obi-Wan, we literally just saw a similar setup with another Star Wars show – The Mandalorian. The Mandalorian protects a little kid, who also gets kidnapped, and who our lead also must retrieve. In other words, nothing about Obi-Wan’s setup feels new or fresh.

Meanwhile, Ms. Marvel leans heavily into Kamala’s culture, which is Pakistani. Now I don’t know about you. But I’ve never seen a high school movie where the main character is Pakistani. And what Ms. Marvel does a great job of is leaning into that culture and exploring the ways in which it affects Kamala’s life.

For example, the Muslim religion is a lot more conservative and, therefore, Kamala can’t wear the sexy things that get girls attention at school, that help them get boyfriends and increase their popularity. So the religion and the culture aren’t just a thin coat of paint. They deeply affect how our hero lives. All of this helps the show feel fresh and new.

Another way the show differentiates itself from Obi-Wan is through the relative importance of this moment in Kamala’s life. For Kamala, this is the single most important thing that’s ever happened to her. She is becoming a superhero. It doesn’t get much bigger than that.

With Obi-Wan, this is nowhere near the biggest moment of his life. He defeated Anakin in Episode 3. That was one. He helped take down the Death Star in Episode 4. That was two. And if we’re to believe all the stories we’re told, he’s done a lot of other big things as well. This is conceivably the 10th, maybe even 15th, most important adventure he’s ever had. Which is why the show constantly feels unnecessary.

As shocking as this might be to hear, Ms. Marvel is also a way better character than Obi-Wan. I can’t believe I typed that sentence so let me clarify it. Ms. Marvel is a better character than THE VERSION OF OBI-WAN THEY GIVE US IN THIS SHOW.

Why is that?

Well, one of the most powerful character types you can create – the character that’s most likely to make people fall in love with your character – is the underdog. Audiences love underdogs. As it so happens, both protagonists in these shows are underdogs. But one underdog we love. And the other we could care less about.

The issue with Obi-Wan’s underdog is that it’s inauthentic. Obi-Wan is made to be this washed up loser who keeps his head down and doesn’t remember how to use the force. Everything about it is manufactured. It doesn’t feel genuine at all. They needed to make him this way to create some semblance of an arc for the series. In order to “get his mojo back” he must overcome his sad sack ways.

Granted, this issue is complicated by things outside the Star Wars writers’ purview. They have a highly restrictive character canon they must work within. But that’s not an excuse. If you don’t have leniency to create a character we like, then don’t make the show. You don’t get to make a show then cry that you had all these restrictions. If you’re going to say, “Watch this,” then you have to stand by the choice you made to bring back a character who doesn’t have anything left to explore.

On the flip side, Kamala’s underdog-ness is excessively authentic. It’s not easy wearing drab clothes that cover your whole body when 99% of your classmates are dressed to attract attention. It’s going to increase the chances that you’re ignored or made fun of. Plus you have this cultural background that not a lot of people understand, which makes you even more of an outcast and, therefore, more of an underdog.

Everything about Kamala’s underdog status feels natural. There aren’t any forced aspects to it. This is something all writers need to watch for. Are you trying really hard to make the audience feel a certain way? If so, the audience probably detects that. And the second someone detects that you’re trying *really hard* to make us like your character, that’s the second we stop liking your character.

Speaking of manipulation, who would’ve thought that a Marvel show aimed at teens would be 1000% more nuanced than a Star Wars show? When Reva bursts out of her ship in her introductory scene in Star Wars, looking for Jedi on Tatooine, she does so with all the subtlety of Happy Gilmore.

I’m two episodes into Ms. Marvel, and the only villain so far is Instagram star, Zoe Zimmer. Zoe has so far been highly nuanced. She’s obsessive about her IG account, yes, but she’s quite friendly towards our hero. This is what a villain should be. They should have bad traits, but also good ones. Even “Obi-Wan’s” late season attempt to explain why Reva’s so angry doesn’t justify her rage. Nothing about her feels organic.

This speaks to a larger problem with Obi-Wan, which is that it’s writing as much to fix problems as it is to create entertainment. It has to weave through so much mythology and plot that it can’t help but feel forced. You can tell that Ms. Marvel has way more freedom in its narrative. The writers can go anywhere they want and, therefore, all they have to focus on is entertaining us.

By the way, this issue can pop up in stories other than those with sequels and extensive mythologies. If you write any kind of story where you’re trying to do too much, your writing will dissolve into the same thing that’s killing Obi-Wan. You’re writing to avoid problems instead of create entertainment.

We saw a gigantic example of this at the beginning of the week, in Jurassic World Dominion. The reason that movie felt so boring was because the writers had to spend the whole time navigating the thick-as-molasses plot rather than just write fun sh*t. There’s a reason they had so much fun with that Dino-motorcycle chase. It was the only scene where they were allowed to let loose and not worry about anything.

There are other things I love about Ms. Marvel as well, which I’m now anointing as the best Marvel show so far. I love that there’s a personal reason for keeping her superhero identity a secret. It’s well-established that her family doesn’t want a daughter who does anything out of the norm. So even if Kamala wanted to tell all her classmates (and the rest of the world) that she was a superhero, she still would’t be able to. There’s no way her parents can ever find out about this or they would disown her.

And that makes this one of the best “has to keep my secret identity” superhero movies/shows yet. I never bought for a second that Peter Parker needed or wanted to keep a secret identity. Honestly, who cares if people know he’s Spider-Man? But with Kamala, since the reason is so personal, you root harder for her to remain anonymous.

There’s also the costume. When I saw the costume in the trailers, I thought, “oh boy, they’ve really hit the bottom of the barrel with superhero shows.” But when you watch the show, you realize that Kamala is the world’s biggest superhero fan. Her dream is to go to Avengercon in cosplay. So she makes that suit herself. Which is why, of course, it’s imperfect. It’s another thing about the show that feels organic, rather than forced.

And the show explores this notion of Instagram celebrity obsession better than any show or movie I’ve seen so far outside of Eighth Grade. Imagine that you want to be popular more than anything. And you have all these people around you who have Instagram accounts that are semi-popular and it makes people like them and boy would it be great if you could somehow have a popular IG also, which would get you more friends and a boyfriend. Then you become a superhero, something that would allow you to have the biggest IG following ever. Yet you can’t tell anybody. The show does a great job showing how frustrating that is for Kamala.

I can’t believe I wrote this article, guys. In a way, it’s cool, cause I found a new show I like. But in another way, it’s sad. Because it shows how far Star Wars has fallen. This is one of their most popular characters and they’ve essentially neutered him. They have to now hope that everybody simply forgets this show existed if they’re to preserve Obi-Wan’s name.

But in order to send the site into the weekend on a high note, I will say that the Vader-Reva lightsaber battle at the end of the latest episode was the best lightsaber battle in all of Star Wars so far. It was really creative. I just wish they would’ve brought more of that creativity to the storytelling.

Genre: Drama/Crime

Premise: An Australian heroin-addict prisoner escapes to Mumbai to disappear, before cozying up with the local mob to make ends meet, and falling in love with a fellow criminal.

About: Shantaram is widely considered to be one of the top 10 books that have not been adapted into a movie or a TV show. After 20 years, all that TV streaming money finally resulted in an adaptation (starring Charlie Hunman, release date TBD). But I recently learned that Eric Roth did a feature screenplay adaptation of the book. Once I found that out, I had to read it!

Writer: Eric Roth (based on the novel by Gregory David Roberts)

Details: 146 pages

Eric Roth is one of the top 10 writers on my Best Screenwriters in the World list. So you know I had to check this out. I read the book years ago. I’ve heard of numerous attempts to make it into a movie since. They just couldn’t make it happen. Let’s see what Roth did with it.

Lin is an Australian heroin addict who robbed and stole to feed his drug habit. This gets him sent to prison. But you can’t keep Lin locked up for long. He orchestrates an escape, heads to the nearest airport, and gets as far away from Australia as possible. Which is how he ends up in Mumbai.

Once in Mumbai, he meets a tour-guide named Prabaker, who may be the most persistent tour guide in the city. Lin asks him only for a hotel recommendation, but Prabaker will not go away. He wants to show Lin the entire city. So he begins driving Lin around, which allows Lin to meet some of the locals.

One of these locals is the mysterious Klara, who Lin is immediately smitten with. Maybe because she’s a criminal like him. Lin also finds himself staying in a local slum, and when he administers a band-aid to someone with a scraped knee, word spreads quickly that the slum has a new doctor. So Lin is a doctor now.

Lin’s ultimate plan is to make it to Germany. But when his passport and all his possessions are stolen, he realizes he is now stuck here, possibly for a very long time. While he fights his way through his love story and navigates the tricky criminal underworld of Mumbai, Lin realizes that he kind of loves this city, and may want to stay for good.

Everybody who reads Shantaram loves it.

Which is why they’ve been trying to adapt it.

But Hollywood has a blindspot whereby they think anything can be adapted. And the reality is that movies work best under a certain type of structure. If your book or video game or Twitter rant doesn’t fit into that structure, it’s not going to work.

Love in the Time of Cholera. A mega-success in the publishing world. But they forced a movie out of that sucker and did anybody see it? No. Because some books just aren’t meant to become movies.

This is one of them.

Shantaram is about a dude who moves to Mumbai and experiences both the good and the bad of the city. But there’s no freaking goal. There’s no ticking time bomb. This is, essentially, travel porn. Really good travel porn.

The level of specificity here is second to none. And that **is** something audiences want to see when they go to the theater. They want to be taken to a place they’ve never been before. You can’t forget that that was one of the original appeals of film. Before we could fly from Los Angeles to Paris in 9 hours, the only way you saw another country was through magazine pictures and movies!

Which is what’s so cool about Shantaram. Cause you don’t just get taken to Mumbai. You get taken to the spots of Mumbai only the locals know about. There’s a moment in the script where they’re walking past all these men who are standing against a wall. Prubaker explains to Lin that these men have all sinned and, therefore, they’ve agreed to stand for the rest of their lives to make up for it. They even have special pole devices to keep them upright when they fall asleep.

That’s highly specific travelogue stuff there that you’re not going to find in any other screenplay.

But, again, there wasn’t enough of a narrative. Book narratives can be powered by questions: “What’s going to happen here?” And “What’s going to happen there?” Open-loop questions are enough to keep people invested. But movies need goals. And they need those goals to have stakes.

Which is why, of course, this was never made into a film, and is instead being made into a show. Books and TV are similar in that they can be built around questions such as, “Will this man and woman get together?” “Will our protagonist slip back into his drug habit?” “Will the local mob boss force our protagonist to commit a crime for him at some point?” “Will our protagonist get in touch with his daughter again?”

Those are all dramatically compelling questions. But notice that they don’t PROPEL THE STORY FORWARD. Jurassic World Dominion was not the best movie but it did have a narrative with strong immediate goals (find and save the daughter, stop the locusts from destroying the food supply) that forced the characters to be active and aggressive.

This is probably why they gave the Shantaram assignment to Roth. He’s one of the few writers who can work with slow narratives. He just did so with Dune. Forrest Gump has an elongated narrative as well.

Mostly he uses the stellar character lineup Gregory David Roberts came up with to distract us from the overall lack of plot momentum.

And Roth has an endless supply of screenwriting knowledge to help him navigate the book’s handicaps. For example, there was a chapter in the book where Lin and Prabaker witness a car crash in Mumbai. And, all of a sudden, pedestrians swarm the car, pulling the driver-at-fault out, and start beating him to death.

Roth includes that scene in the script, but he smartly places Lin and Prabaker in the car that gets in the wreck. That makes the wreck more personal, as well as more dangerous. Cause now, they’re in danger of being beaten themselves. That’s a great screenwriting tip. Always try to bring your characters closest to the action. You don’t want something cool to happen far away from your protagonist. You want them to be involved.

Probably the best example of why you pay 1.5 million dollars to have Eric Roth adapt your book is the way he handles his main character’s backstory. When Lin is in Prubaker’s village, he wakes up after a long night’s sleep and finds a little Indian girl sitting next to him with a tea set.

The girl starts talking to him in a language he can’t understand and it becomes clear she’s talking about herself. So when she stops, Lin takes it upon himself to tell her his story as well. Of course, she can’t understand him either. But it becomes a very clever way for Lin to explain a ton of backstory about himself, all in a way that feels honest. I don’t think I’ve ever seen exposition done quite this way before. And I consider it genius.

Roth also recognized that he had a goldmine in Prabaker. As I’ve told you before, if you want to write great dialogue, you need to look for DIALOGUE-FRIENDLY characters. You don’t get good dialogue out of introverted folks who carefully choose their words. Prabaker is like a coked-up Mumbai version of Yoda.

“Very few foreigners know how to speak this language, Marathi. There is only one other tourist I tried to teach to it. But he was hit by a bus who didn’t want him crossing the street when he was not looking.”

He was a single-handed lightning bolt on every page. You wanted to read whatever Prabaker said next. Which is when you know you’ve got a winning dialogue character (and a winning character in general).

Roth is such a good writer that he makes this script work. But only for what it is. Which is a distilled down version of the novel. This book was never going to work as a movie. But it was fun to read such a great writer’s attempt at it. I’m guessing it was the best draft of everyone they hired to try. Which I understand was a lot of writers.

Screenplay Link: Shantaram

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: A structure that they might have been able to use here is that Lin doesn’t want to stay in Mumbai. But when his fake passport is stolen, he’s stuck here. So that gives him his goal. He’s got to save up enough money to buy a new fake passport and a plane ticket to his final destination (we’re told he ultimately wants to end up in Germany). That gives him anywhere from 2-4 weeks here in Mumbai, which is plenty of time to experience all the city’s craziness and keep a tight enough timeline that the story contains momentum. You would then put him at the airport at the end with a choice. He’s kind of fallen in love with this city. But he has bigger goals in Germany. Does he stay or does he go? I think that’s a better structure than what we have here, which is too loosey-goosey.