Search Results for: F word

Week 0 (concept)

Week 1 (outline)

Week 2 (first act)

Week 3 (first half of second act)

Week 4 (second half second act)

Week 5 (third act)

I had a contemplative moment this weekend.

I was trying to find something to watch after a long day of work. I checked Netflix. I checked HBO Max. I checked Disney Plus. I checked Hulu. I checked Peacock. I checked Amazon Prime. I even sat around for several minutes convinced that I owned another streaming service that I’d forgotten about.

Long story short, I couldn’t find anything to watch.

But that’s not what made me introspective.

The sheer volume of movie/show thumbnails I scrolled through was an eye-opener. There was so much. I still remember the days when you turned on the TV and you had five choices. You went to the movie theater and you had one, maybe two choices.

To see all of this stuff in front of me available with a single click was almost scary. How can any writer possibly surprise an audience anymore? Or write something original?

There are only so many ways you can arc a character. There are only so many plot tricks you can use. There are only so many ways you can tell a story. Is it even possible, anymore, to write something that feels unique? That feels honest and original? Has this ocean of media swallowed that option up?

I thought about that for a long time. I had two good hours since I wasn’t able to find anything to watch, remember.

I came to the conclusion that, yes, it is still possible to achieve these things. The analogy that convinced me was that we have billions of people on this planet. We run into people all of the time. And yet we still end up meeting people we really like. Maybe as a friend. Maybe as a romantic interest. Maybe as mentor or a business connection.

In other words, we never get bored of people, despite how many of them there are.

That tells me that we’ll never get bored of good TV shows and good movies.

However, we must concede that there is more competition for storytelling than ever before. And, for that reason, giving 65%, 75%, 85%, even 95%, of what your story could be isn’t enough. It has to be 100%. You have to give your all. You have to be able to look at your script and say, “This is the best I can do.” If you want ANY shot at breaking into the business, that’s the bar you need to clear. Because there are plenty of above average projects floating around Hollywood. You need to write something beyond that to get noticed.

The question then becomes, what gets you to 100%?

The answer is REWRITING.

Most first drafts will be lucky to cross the 50% threshold. That means, after one draft, your script is 50% of what it could be. Which, obviously, means, you’ve got 50% to go. While it would be nice if that 50% was writing a second draft, that’s not how it works. If you’re doing it right, your second draft might get you to 65%. And, from there, you’re aiming for each draft to get you another 5%. If you can write a great script under 10 drafts, you’ve done an amazing job.

Remember that Good Will Hunting was rumored to have 50+ drafts. Uncut Gems had something like 200 drafts. But I consider that overkill if you’re doing your job right. A good rewriting strategy can get you to that 10 draft marker.

So what is rewriting?

Rewriting is about identifying problems in the current draft and coming up with solutions. And that’s what we’re going to do this week. We’re going to read our script and we’re going to figure out the five (rough estimation, could be more or less) biggest things that are wrong with it. But in order to do that well, you need to put your script down for at least a few days. That means, either Wednesday or Thursday, you’re going to pick your script back up and read the whole thing from start to finish.

What I want you to focus on while reading is how you feel during the read. Don’t focus on characters or plot yet. Just focus on, are you bored? Are you annoyed? Is this section good? Is this section bad? Your emotions will signal to you when something isn’t working. Write all that down. Note every time where something doesn’t feel right. Or even doesn’t feel as good as it could be.

Once you’ve done that, go back through your notes and ask WHY you felt that way. The WHY is where you will find your answers for how to approach the next draft.

I’m working with a writer on a sports script right now and one of the first things we noticed while re-reading the script was how disinterested the main character felt. This was by design, something that the hero would learn and correct over the course of his character transformation. But it didn’t work. The disinterest led to a passive character, and that’s something you can’t have in a sports movie. Your hero needs to be active.

There were also subplots that didn’t work. Whenever our hero was around certain characters, their scenes would drag. It was a telling sign that those characters weren’t working.

There were also parts of the script that felt disconnected from the main storyline. This was a sports movie and yet certain situations had our character a thousand miles away from his sport. There were legit reasons why these choices were made during the writing of the script, but if something doesn’t work, it doesn’t work.

One of the hardest things to get right is your hero’s transformational arc. They start with a flaw. They gradually learn about their flaw. And then, at the end, they overcome the flaw. This is hard to execute in a first draft because flaws are negative and you want your hero to be likable. So you’re trying to find that balance between likable and flawed. And then you’re trying to set up an ending that organically allows your hero to overcome the flaw. It’s asking a lot of one draft. So you almost always need to play with this and fine tune it over multiple drafts.

Sometimes things just don’t work out the way you thought they would. Your amazing villain turned out to be cheesy and forgettable. All of this is common in a first draft and none of it should deter you. This is what rewriting is about.

So I want you to read your script Wednesday or Thursday with fresh eyes. I want you to write down everything that isn’t working. And then just start to consider solutions. Some solutions will come to you quickly. For example, if your hero is unlikable… give him a couple more likable traits! Or add a save the cat moment.

Some solutions you won’t have answers to right away. I once wrote a comedy script with four main characters (think Eurotrip). Three of them were guys. One was a girl. And it just wasn’t working. The energy my female character was bringing wasn’t funny for some reason. So I battled over getting rid of the female character and replacing her with a guy. But then it’s an all guys movie and that didn’t feel right either. So maybe I needed to reinvent her so she was funnier.

You have to make decisions like that all the time in screenwriting. Sometimes you have to marinate on these problems for a while before you come up with a solution. That’s what this week is about. It’s about reading your script, figuring out what isn’t working, writing down the obvious solutions, then taking the rest of the week to try and solve the more complex issues.

The good news is, you don’t have to figure everything out this week. Normally, I prefer you have at least a month before you write your second draft. You want a solid plan going into this draft. But we’re working on an accelerated schedule, so we’re going to do this in two weeks. This week is about identifying the problems. Next week is about coming up with an official outline for our second draft.

For those of you who want to rush this and start your second draft right away, I encourage you to try this method instead. At the beginning of this post, I talked about the unbelievable volume of media you’re competing against. To be better than all those other thumbnails, you need to take this seriously. You need a plan of attack every time you write a draft. That’s what I’m trying to teach you. Have a plan of attack so that you get the most out of each draft. That way, you’ll get 15% closer as opposed 3% closer.

A big shout out to everyone who’s stayed up to date with their writing. Awesome job. I’m super proud of you!

And how can we steal their secrets for features?

The only thing that matters right now is that they’re finally building a real lightsaber. Not those fakey glorified glow-sticks but a real live lightsaber that rises up from the handle. I will be the first one to buy this when it comes out, even if it means dipping into my retirement fund. There are some things that are more important than long-term financial security. Five Guys French fries and lightsabers are near the top of the list.

In non-lightsaber related news, I was recently thinking about how rare it is to find a funny movie. Yet there are a ton of funny television shows. That got me wondering why television seems to be such a better format for comedy. I was hoping that, if I examined that paradox today, I might be able to discover a few things about why TV is better for comedy and steal those lessons for the feature world.

Let’s get into it!

The sit-com seems to be the master laugh-generating format. From The Jeffersons to Cheers to Seinfeld to Friends to Modern Family to South Park to Broad City to Curb Your Enthusiasm. These shows figured out a formula to keep you laughing for 30 straight minutes. And they do it week after week after week.

Meanwhile, how many great comedy features did we get last year? The most recent comedy studio release was The War With Grandpa. Anybody see that? I didn’t think so. 2020’s comedy behemoth was Like a Boss, a movie with a trailer so unfunny, it reportedly killed the editor’s ability to laugh. 2019’s big comedy was Goodboys, which is, arguably, the best studio comedy of the last three years. If that doesn’t tell you where we are in the feature comedy world, I don’t know what does.

Part of the problem is that all the things that make movies great don’t transfer well to comedies. With Hollywood movies, the sets are always bigger. The effects are always bigger. The locations are always bigger. The overall production design is stronger. This is what helped them create Titanic, The Avengers, Terminator 2, Fast and Furious, The Dark Knight Rises.

But none of those things matter in comedy. I suppose bigger locations and bigger sets are important for action-comedies like Spy. But there has never been a correlation between bigger budget and bigger laughs. In fact, I’d argue the opposite is true. The more expensive a gag, the dumber it usually is.

There’s a scene in Spy where Susan is on a private plane that gets hijacked and we get a five minute “comedic” sequence where they’re going in and out of zero gravity. There wasn’t a single laugh in the scene. And I’m guessing the sequence took 4-5 days to shoot and was one of the more logistically complicated scenes. I wouldn’t be surprised if the price for that scene came out to 4 million dollars. For zero laughs!

A good laugh usually costs nothing but the the actors you’re paying and the writer who wrote the joke.

One big advantage TV has over movies is that, other than the pilot episode, TV doesn’t have to set up its characters. That is huge. Character set up is public enemy number 1 for feature writers. Before you can laugh at a character, you must understand who they are. You must first understand the contradiction of George Costanza (neurotic, dim-witted, yet oddly entitled) before you can appreciate his interaction with the soup nazi, a man he’s been told never to question, yet when he’s not given any bread with his soup, he can’t help himself. He must bring up the injustice.

But that George is not present in Seinfeld’s first five episodes. It takes a while for us to understand that that’s who George is. Unfortunately, movies don’t give anywhere near that much time to establish a character. You have two, maybe three scenes, to convey to an audience exactly who your character is. And that creates some limitations. Out goes complexity. Out goes subtlety. This forces you to create one-dimensional on-the-nose characters who don’t feel like real people.

That’s a key detail that a lot of people forget about comedy. Yes, almost every comedic character is an exaggeration. However, they still need to be based on people we feel like we know. In other words, they have to be based in reality. We all know someone like George Costanza who can’t help himself. He *must* die on that hill, even when all the data suggests it’s not a hill worth dying on.

So, character is the first hurdle feature comedy writers must leap. Spend as much time as possible coming up with really funny characters then figure out how you’re going to convey that particular brand of humor in a few short scenes at the beginning of your screenplay. I mean who doesn’t know who Annie in Briedesmaids is after her first scene?

That’s the scene where Annie’s having sex with a douchebag character played by Jon Hamm and even though the sex is horrible, she’s desperate to be his girlfriend, sneaking into the bathroom before he wakes up the following morning to do her hair and make-up so that when he does wake up, she can pretend this is how she always looks. That desperation to find someone helps us understand Annie’s jealousy issues at her best friend getting married AND having to share maid-of-honor duties with the bride’s new best friend. Annie’s jealousy is the engine for almost her entire comedic performance and the setup of that character was a big reason why that worked.

The second big difference I noticed between comedy in TV and film is the way they go about their laughs. TV is mainly about creating a series of comedic situations. “Situation” is the “sit” in “sit-com.” “Situation-comedy.” So as a sit-com writer, you’re basically looking to find funny situations. Plot isn’t that important. There obviously needs to be some setup involved and that requires exposition and, possibly, an earlier scene or two. But if something requires too much setup, you don’t want to mess with it in television.

I’ve noticed that a lot of comedic TV situations are based on misunderstandings. One of my favorites occurs in Modern Family when Phil (the well-meaning but clueless dad) befriends a guy at the gym (played by Matthew Broderick) who he has no idea is gay. Phil invites the gym friend to his house to watch a basketball game (they share the same alma mater), having no idea that the friend is interpreting this as a hook-up opportunity. The *situation* plays out with Phil cluelessly rooting his basketball team on while high-fiving and hugging the gym friend, who keeps attempting to escalate the physical contact into something more (signals that Phil always misses).

Meanwhile, feature films, for some reason, shy away from situational comedy. Instead, they replace this with “set-piece” comedy. Set-pieces such as the famous dinner scene in Meet the Parents where Greg attempts to tell Jack that anything that has nipples can be milked. This both sort of makes sense to me and sort of doesn’t.

It would make sense that, because a movie is longer, you have the opportunity for longer scenes. But longer scenes require more setup to make them work. And setup is often unfunny. You try and make it funny, of course. But the underlying purpose of a setup scene ensures that it always feels like setup. And those scenes are always the most boring. One of the things that separates A-list comedy writers from everyone else is the ability to construct their setup scenes so that they’re individually funny scenes themselves and the audience doesn’t realize they’re being set up.

Think about that dinner scene in Meet The Parents – how much setup that required. You needed to establish that Greg had a ‘wussy’ job. This will be important later when you set up that Jack had a ‘manly’ job. You need to setup that Greg was just about to ask his wife to marry him before learning how important it is in their family to get the father’s approval first. You need to have Greg lose his suitcase on the flight. You need to set up her family and the wedding that’s going on that weekend. All of that stuff works its way into the dinner set-piece.

If you don’t do that or don’t know how to do that, you won’t have enough jokes to pay off. A joke punchline needs a joke setup and a set-piece is often the climax of a bunch of joke setups.

However, there’s something deeper going on here. I’m trying to imagine putting the Modern Family situation I mentioned above into a movie. Could you do that? I’m not sure you could. There’s something about a movie having a bigger overall theme and plot that would make a surface-level misunderstanding like that seem insignificant. And yet I don’t want to deprive comedy writers of such a strong comedic device. Obviously, something is wrong with the feature comedy format. We should be getting more than one funny studio movie every three years. Is the fact that it is so set-piece driven, and set-pieces are so much harder to pull off than situational comedy, the problem?

I need more time to study this but something tells me we can blend both situational comedy and set-piece comedy into a hybrid ‘situational set piece’ scenario that offers the best of both worlds. I’m sure some of you will point out movie scenes that do just this so I’m all ears. I’m ready to learn.

For now, though, those are the two lessons I want you to take away from today’s article. You need to put an insane amount of focus on figuring out your comedic characters and then even more focus on introducing them in a way where the audience immediately understands them AND what’s funny about them. Some sit-coms benefit from the fact that they’ve had two seasons to fully discover a comedic character. You don’t have that luxury so you need make up for it by nailing the introductory scenes.

The second lesson is that situational comedy is easier to pull off than set-piece comedy. And situational comedy is used so frequently in television shows that when a situation doesn’t work, you immediately have a shot with another one. Meanwhile, there’s so much time between set-pieces in movies that if even one of them doesn’t land, it could be the difference between a good and a bad comedy. Because who wants to wait 25 minutes for the next big laugh? For this reason, you must nail all the setup for your upcoming set piece so that you have a lot of jokes to pay off. And if a set piece isn’t working, you need to get rid of it and find another one. You don’t have the flexibility, like sit-coms do, to fail. Your set pieces all have to be the best you’re capable of.

I hope this helps!

I’m thinking of reviewing Stone Thunder or whatever that dreadful new Melissa McCarthy Ben Falcone superhero comedy on Netflix is called this Monday. I wouldn’t normally bother but it is a comedy and it’s obviously terrible so maybe we can learn something from it? Vote in the comments below!

Guess what day it is?

It’s SCRIPTSHADOW WRITE A COMEDY SCRIPT IN 3 MONTHS BEGINNING OF WEEK LIST OF THINGS FOR YOU TO DO THIS WEEK day.

For those unfamiliar, Comedy Showdown is going down June 17th. That’s the submission deadline. In the meantime, I’m helping you write your script. I’ve already done Week One here and Week Two here. But even if you didn’t know about this until now, there’s still plenty of time to write a script. You’ll just need to up your pages-per-day. At the moment, I’m asking for 3 and a half pages a day. You might have to up that to 5 pages. Or, if you’re okay with not doing a final polish on your script, you can stay at 3 and a half pages.

Now, a little structure talk here so you understand what we’re going to be doing over the course of this week. For starters, we’re structuring our comedy assuming it’ll be 100 pages long. For our first draft, we are writing 1/4 of our script a week. Last week we wrote the first quarter (pages 1-25). Now we’re going to write the second quarter (pages 26-50).

This will take us to the script’s halfway point.

To make things easier for you, we’re going to be using the Sequence Approach and dividing this quarter into TWO SEQUENCES, each of them 12 and a half pages long. The first of those (pages 26 – 37.5) is commonly known as the “Fun and Games” sequence and is, arguably, the whole reason your came up with your idea. This is the section where you aggressively deliver on the promise of your premise.

Think about that first moment when the guys woke up in The Hangover. There’s a baby. There’s a tiger. Someone’s missing teeth. Those next 12 and a half pages delivered on the promise of the premise of waking up after a crazy night out and having no idea what happened the night before.

Or take Coming To America (the original). This is the moment where Prince Akeem and Semmi show up in Queens for the first time. You got the crazy New York cab driver who speaks his mind. The guys finding out that “Queens” is nothing like it sounds. Trying to get an apartment in New York for the first time. You are literally leaning into all of the funniest gags you can come up with from two guys who have never been to America… coming to America.

In other words, this should be the most fun you have the entire script. If you’re not laughing as you come up with fun new scenes for this section, you probably picked a lousy idea.

Where things get tough is in this second of the two sequences you’ll be writing this week (pages 37.5 to 50). This section isn’t as clear. In fact, I don’t know if anyone in screenwriting history has given it a name yet (feel free to suggest a name in the comments). But the good news is you know the exact number of pages it has to be – 12 and a half – which isn’t that many. And you know exactly where this sequence ends – it ends at your screenplay’s midpoint. Which means you can write towards your big midpoint moment.

The midpoint of a script tends to be the time where something big happens. That thing could be negative or positive. As long as it’s A BIG DEAL. It should also, preferably, alter the script in some way whereby the second half of the movie doesn’t feel exactly like the first half. This is a common newbie mistake. New screenwriters make the same jokes for 100 pages. You need something that alters the plot so that the jokes (and story) feel different.

I recently rewatched “Spy,” and the midpoint of that script is a positive one. It’s the moment where our spy, Susan Cooper (Melissa McCarthy), finally befriends target Rayna Bayanov, while having to maintain her cover. The entire first half of the movie was built around Susan trying to get to Rayna. In the second half of the movie, she befriends her, but must keep her cover. That change creates a whole new set of plotlines and jokes.

In Guardians of the Galaxy, which is essentially a comedy, the midpoint is a negative one. Peter Quill and his team lose the orb to big baddie, Ronan. This, of course, sets the stage for the second half of the script, which will require our misfit team to retrieve the orb before the bad guys activate it, destroying the universe.

During both of these sections, I want you to be focusing on two things. One, keep throwing obstacles at your hero. Especially in the second sequence. The first sequence – our “Fun and Games” section – is more about having fun with the concept. But having fun is often about throwing things at your hero that they have to deal with. So you’re going to pepper some of that in there as well.

Once out of the Fun and Games section, you’re in slightly more ‘serious’ territory. So you’re going to ramp up the obstacles. For example, in “Spy,” you’re going to throw an assassin at Melissa McCarthy. You’re going to blow her cover when she’s in the middle of a difficult task. Think of yourself as the “Obstacle God.” Your job is to create obstacles that you then drop into your film.

Comedy is often about being as shitty as possible to your hero and watching them squirm. That’s where the fun is! If you aren’t challenging your hero consistently, there isn’t going to be a lot of opportunity for laughs. If you find yourself writing dialogue scenes where you’re desperately looking for the next joke between two characters, chances are you’re not throwing anything at them. You’re leaving them to blow aimlessly in the wind – and that’s where comedy dies. When you throw obstacles at your hero, you don’t have to look for laughs. The laughs organically come to your heroes as they swat away all the shit you’re throwing at them.

The second thing I want you to focus on is reminding the reader what your hero’s flaw is. You do this by continuing to give them opportunities to overcome their flaw only for them to not be up to the task yet. Obviously, if they were up to the task, your movie would be over.

Look at Steve Carrel’s character in The 40 Year Old Virgin. His flaw was arrested development. He’s still stuck in his childhood, which explains why he hasn’t had sex yet. As a writer, you want to challenge that flaw to remind the audience what it is your hero has to overcome. In this case, Steve Carrel’s girlfriend suggests he sell his valuable childhood action figures to start his dream business. Carrel resists this, at first, to let the audience know he’s not ready. He hasn’t overcome his flaw yet.

If you don’t occasionally remind the audience of this over the course of your screenplay, then, at the end, when you try and write your big heartstrings-tugging moment, there ain’t gonna be any tears. And you’re going to ask people, “Why aren’t you crying?” And they’re going to say, “Because that whole ‘he’s finally ready to grow up’ moment came out of nowhere!” “Came out of nowhere” is code for you didn’t set it up properly. Which is why you need to keep reminding your reader that your hero hasn’t overcome his flaw yet.

One last thing. Don’t worry if your page count is a little long. If it feels like you’re going to hit 120 pages instead of 100, that’s okay. I’ve found that, in comedies, there are always going to be a few characters you don’t “get” the first time around. You’re trying to find where their ‘funny’ is in that first draft. And the best way to do that is to let some scenes run long so that your ‘trouble’ character gets a chance to find his voice. That might even mean changing him in the middle of the script because he wasn’t working in the first half. In the end, the biggest thing you’re going to be graded on is, “Is this funny?” So if characters aren’t working, you need to play with them and give them opportunities to let go. Sometimes it’s a single line you write that helps you finally ‘get’ a character.

Wow, at the end of this week we’re going to be halfway through our script! Who said writing a screenplay was hard?

Onwards and upwards!

Writing great comedy scripts does not come down to plot or theme or even, as commonly assumed, dialogue. It comes down to how funny the key characters are in the script. Are they constructed in such a way that they are inherently funny without having to do anything?

When you manage to construct an inherently funny character, it is magic fairy dust for your screenplay. You don’t have to think of funny things for them to say or do. They just say and do them. Contrast this with weak comedy characters who you always seem to be moving mountains for to get just one funny line out of them. Get the character right AND HE BECOMES THE COMEDY.

What we’re doing today is listing ten great comedic roles and you’ll see pretty quickly that there’s overlap. In other words, pay attention to the kinds of characters who become iconic because their DNA on ‘how to write funny’ is right there for the taking if you want it.

Here we go!

Alan in The Hangover – Alan’s primary characteristic is that he’s the most socially unaware person in the world. Combine this with a character who likes to talk a lot and you get someone who’s always going to be saying funny things. This is a comedy staple. You saw it with Dwight in The Office. You saw it with Kramer in Seinfeld. There are variations here on how goofy you want to get with these characters. But socially unaware characters who like to blast their opinions on everything consistently become some of the funniest characters out there.

Walter from The Big Lebowski – Aggressive. Mentally unstable. Paranoid. Note the extremes of the adjectives we use to describe Walter. He’s not “kind,” or “sweet,” or “pleasant.” He’s AGGRESSIVE. He’s PARANOID! Big exaggerated negative traits are great for comedy. We also have a character, like Alan, who loves to talk! Characters who express what’s on their mind have more ‘funny potential’ than characters who keep to themselves.

Derek from Zoolander – Derek is really really really really really really really dumb. Again, note the EXTREME here. Extreme works well in comedy. If Derek is only sort of dumb, there aren’t as many laughs. Also, Derek plays into a stereotype – that all models are dumb. While everyone is freaked out about stereotyping these days, it’s one of the best ways to construct a funny character. For example, if they made Zoolander today, it would not be controversial. Find that stereotype and play it up!

Ron Burgandy in Anchorman – His name is Ron Burgandy? Ron Burgandy exhibits another staple for hilarious characters. He’s clueless. The guy has no idea what’s going on around him is usually funny. But where you get those big laughs from Ron Burgandy is that he thinks he’s amazing. That’s always a great combination to play with in comedy. You take a negative and you contrast it with a positive. This guy’s so clueless. And yet, if you asked him, he’d tell you he’s the second coming of Christ. That gap between who he is and who he thinks he is is where all the laughs are.

Megan from Bridesmaids – Melissa McCarthy stole Bridesmaids with this character and she has the writers to thank for it. Megan is your classic “no filter” character. Comedy LOOOOOOOVVVES no filter. An additional note with this character. The temptation is to look for her laughs from dialogue. Don’t limit yourself. Extend the ‘no filter’ mindset to that character’s actions as well. One of the funniest moments in Bridesmaids is when Megan steals nine puppies from the wedding party.

Stifler from American Pie – We’ve got our first villain! American Pie did something really genius with Stifler which is why he became the most memorable character of the franchise. He got it as much as he dished it out. He makes fun of everyone but gets peed on at the party. He cusses nerds out but ends up drinking a beer full of semen. He beats people up yet a nerd has sex with his mom. This supports my theory about contrast being the key to comedy. If Stifler is just a dick the entire time and never gets payback for it (until the last scene), we don’t experience any contrast in his character. It’s going from one extreme (a Stifler win) to the other (a Stifler loss) that keeps his character hilarious.

Happy Gilmore – Happy Gilmore plays with one of the simplest comedy types available: the angry dude. People who get insanely angry are funny. If Happy Gilmore is only kind of angry, his character doesn’t work. Instead, this is a guy who tries to beat up national treasure Bob Barker from The Price is Right (The Price is Wronnnng, bitch!). Comedy’s often about going one yard further than the audience expects you to go. Happy Gilmore has 30+ examples of that. And it’s a great approach to writing comedy in general. Think about where the reader expects you to go with the joke, and then take one yard further.

Vizzini from The Princess Bride – We’re adding a second villain to the list. Inconceivable! Vizzini is built around his outsized ego. This is another area where we find contrast. Vizzini is this tiny little man. Yet he has the biggest ego of anyone in the movie. It’s that contrast (or irony) that makes the character so fun. And, again, you see that comedy works well with extremes. Vizzini believes he’s the most intelligent person in the world. He believes everybody’s not just dumber than him, but WAY DUMBER than him. That’s where you want to be thinking with comedy. You want to go to those extremes.

Borat – Misguided confidence is one of the funniest traits you can play with. Why is Borat so confident? Why does he walk into every situation with such assuredness? That contrast between his extreme confidence and engaging with a country he knows nothing about is where all the fun is. Borat is not funny if he’s constantly doubting himself. He’s not funny if he’s depressed and uninterested in his surroundings. He’s funny because of his outsized confidence in a number of scenarios where there is no reason for him to be confident at all.

Stapler Guy in Office Space – I thought I’d put Stapler Guy in here because he’s so unlike any other character on this list. Most of these characters are loud and in your face. Stapler Guy is quiet and mumbles all the time. So why is he still funny? Mike Judge flipped the script on this. Most funny characters are built around what they put out into the world. Stifler and Ron Burgandy and Happy Gilmore – these are all people who throw their personalities into the world. Stapler Guy is the opposite. His entire persona is built around how the world treats him. Nobody respects him. That’s the joke. People keep kicking him and kicking him and kicking him. And I think that’s why he’s so funny, is that a lot of writers would start to feel bad about kicking someone so much. Mike Judge doesn’t. He just keeps kicking. And he adds this brilliant little twist whereby Stapler Guy tries to fight back but nobody can hear him because he’s a mumbler. Sometimes being RELENTLESSLY HORRIBLE to your character can make him hilarious.

Genre: Comedy

Premise: An action comedy wherein Benji Stone, a lovable but deeply unpopular sixteen year old, is pulled into an international assassination plot by his uncle, a retired undercover assassin charged with babysitting Benji for the weekend.

About: This script finished with 8 votes on this past Black List. The writer, Gabe Delahaye, has written a little bit for TV. Despite having a few feature scripts in development, he doesn’t have a feature credit yet.

Writer: Gabe Delahaye

Details: 115 pages

Err, remember when I said go write a John Wick comedy? I guess I wasn’t paying attention. Somebody already did that. And here it is!

Benji Stone is just a 16 year old Northern suburbs of Chicago dork who likes robotics. The guy’s sole objective is to get into MIT. Well, that’s his sole objective initially. Objectives are about to radically change for Benji in about 24 hours. But, meanwhile, he and his best friend, the super popular Lakshmi, need to decide if they’re going to a party tonight.

That decision is made for Benji, though, since his mom is going out of town and his uncle, Gideon, will be staying for the week, babysitting him. It turns out Gideon is kind of a nightmare. His questionable fashion choices (he wears a baby blue “Frozen” hat) are usurped only by his complete lack of humanity. The guy has the social graces of a Buckingham Palace guard.

Gideon makes Benji take him out to eat (Benji picks Denny’s) and that’s Benji’s first clue that something isn’t right here. Gideon drives a $300,000 McLaren. It is at Denny’s where some random guy comes up to their table, tells Gideon he looks like an old friend, and takes a picture of him. This odd moment is followed by Gideon walking into the parking lot and BEATING THE LIVING SHIT OUT OF THE GUY UNTIL HE’S DEAD!

Gideon comes clean to Benji. He’s an international assassin. A retired one. He’s been hiding out for years to convince the world that he’s dead. This was his first step towards trying to live a normal life. And now he’s back on “the board.” And, oh yeah, now that all the assassins know of Benji’s existence, it means that he’s on “the board” as well.

There are not many 16 year olds who can handle being told there’s a million dollar payday on their head and Benji sure isn’t one of them. He begins freaking out. But Gideon assures him that with a little training, he can make him a killer too. Uhhh, Benji says. I DON’T WANT TO BE A KILLER. But it’s too late for that.

Benji tries his best to ignore this horrifying new reality and goes back to school, starting with his driver’s ed test, a test that Gideon insists on joining. It’s a good thing he does. Cause in the middle of it, a group of motorcycle assassins attack them! Gideon leaps into the front seat but is forced to only control the gas and brake while Benji steers their way to a dozen near death crashes.

Benji remains in denial, going to school the next day. But he regrets it when their new “substitute teacher” has quite the strong Eastern European accent. Yes, she’s a killer too! And she attacks Benji! Gideon shows up just in time to take her out. But he informs Benji that the situation is dire. The woman he just killed is the sister of a major crime boss. If she showed up, he won’t be far behind. And this guy is the kind of killer that makes all these other killers look like mannequins. Both Gideon and Benji will be pushed to their limit!

Question #1: Does this pass the comedy concept test?

It does. The comedy concept test is, when you hear the idea, do you automatically think of a bunch of funny scenarios. “Uncle Wick” immediately makes you think of a bunch of funny scenarios. So, right off the bat, it’s looking good.

Question #2: Does this pass the comedy trailer test?

This is kind of like question 1 but it helps you get a better sense of if this is a movie or if it’s just a funny script. Try to imagine the trailer. Does it have a bunch of funny scenarios that will look great in a trailer? This does. The ‘John Wick joins the driver’s test” set piece was genius. Killing your nephew’s substitute teacher in the middle of school is also funny.

Question #3: Is the dialogue funny?

On this one, Uncle Wick is hit or miss. The dialogue is okay. But I would’ve preferred laughing out loud a lot more. A lot of the dialogue humor is built off of the relationship between Benji and his uncle. It’s Benji going crazy and his Uncle, who’s used to doing this stuff all the time, responding with dozens of variations of “What’s the big deal?” And these moments *are* funny. But I was hoping for some more wordplay. Funnier phrasing. Some more clever back-and-forth. It kind of kept hitting that same beat the whole time.

The script’s biggest weakness is that all the focus is put on Ben and the Uncle’s storyline – which is where the focus should be. That’s the concept. But it’s clear that Delahaye didn’t put nearly as much thought into Ben’s life. For example, Ben is described as the biggest nerd in school. Then, two pages later, we introduce his best friend, a girl who is the most popular girl in school.

Uhhhh, what????

We’re just expected to go with that? Um, no. That’s the kind of friendship that needs more explanation. And this continued throughout the school stuff. It was all rather thin. The bully had the lamest bully lines ever. Ben was trying to get the hottest girl in school to go to the dance with him.

It’s not that these things shouldn’t be used. They are high school movie staples. But they only work when you twist them slightly. So they feel a little unique. That uniqueness is what sets your high school script apart from everyone else’s.

Another issue with the script is the structure. Typically, in these movies, you go out on an adventure. A good example is The Spy Who Dumped Me. That movie sends its protagonists off on an adventure. And whenever your characters are on the move, it’s easier to structure, because the objectives are always destinations, and you can double those destinations up as major plot beats.

Here, they stay in town. And that presents challenges, which we see rearing their ugly head later in the script. For example, once we’ve established that there’s a million dollar price tag on Benji’s head, why is he going to school?

Clearly, the reason he’s going to school is so the writer can get in his Substitute Teacher Fight Set Piece. Which is great for them, but lazy for the storytelling. We needed a clearer time frame and goal for our heroes. Otherwise, you get your heroes waiting around for the bad guys to show up, and EVERYONE HERE knows how much I hate ‘waiting around’ plots. They cause way more trouble than they’re worth. You want your heroes to be active and driving the plot, not the other way around.

In the end, there’s enough juice in this comedy bottle to make it worth drinking. It’s not perfect but it was a welcome upgrade from the script that I started to read for today’s review – Black Mitzvah. Oy vey. Do NOT read that if you want to laugh.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

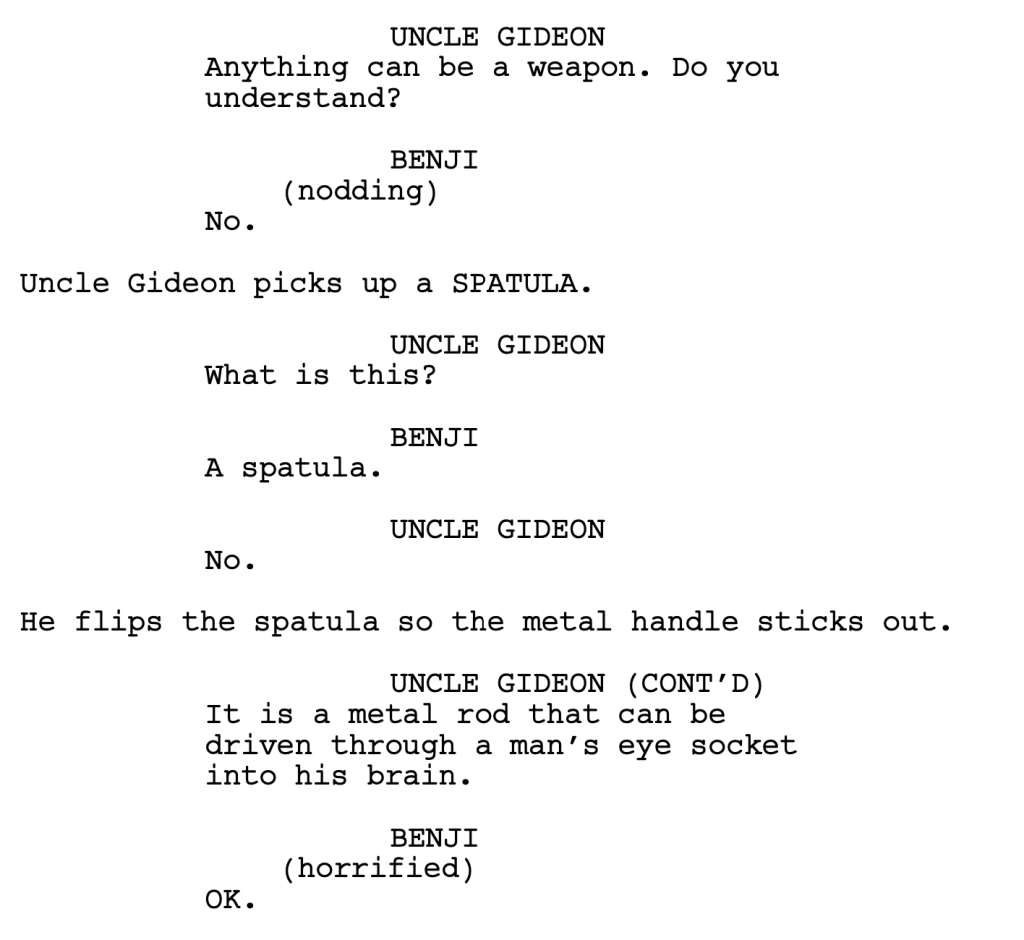

What I learned: DRESSING UP DIALOGUE – You are writing a comedy, correct? So it doesn’t make sense for your characters to say things in a straightforward manner (unless that’s the kind of character they are). Early in the script, Benji’s friend knows something about Benji’s crush that can help him get her. So she tells him that. Now before I give you the sentence she uses to convey that, I want you to write your own version of what she says. Because, what you’re trying not to do is something like this: “Hey, I heard something about Heather that can help you.” That line is fine in a drama. But this is a comedy. So how can you dress that line up? Here’s what the friend actually says to Benji: “Speaking of something weighing on your conscience, if I give you a piece of Heather intel, promise not to let the police know I helped you plan her murder?” So much more creative. It’s not laugh out loud funny. But it gets a giggle. And that’s how you want to be thinking when you write your comedy dialogue lines. Dress them up.