Search Results for: F word

Today’s screenplay cleverly combines the core relationship of Terminator 2 with the wacky video game premise of Jumanji: Welcome to the Jungle.

Genre: Action/Adventure/Comedy

Premise: After a marauding warrior from a popular video game dies, he is reincarnated in our world and discovers the god he’s always worshipped turns out to be a 13-year-old Asian kid from New Jersey.

About: I was just talking about this project on Monday. It’s the spec script Amazon picked up from Jeff Chan and Andrew Rhymer for high six-figures. David Leitch, who is not so quietly building an empire, is producing. It’s amazing how fast your star can rise in this town. This guy was a life-long stuntman. Now his movies are responsible for over 2 billion dollars at the box office and he’s producing everything in town. Yowzers!

Writers: Jeff Chan & Andrew Rhymer

Details: 111 pages

I’m a sucker for these concepts. I love when people from one realm are dropped into another realm. I loved Enchanted’s concept. I thought Jumanji: Welcome to the Jungle was fun. Elf was a classic, of course. Fish-out-of-water ideas are some of the best ideas you can come up with because they’re a perfect fit for the movie formula.

I liked what today’s writers did. They basically looked at Jumanji and said, “What if we went in the other direction?” Take a character from the game world and place them in the real world. When screenwriting websites tell you to come up with ideas that “are the same but different,” this is exactly what they mean.

If Johnson and Chen had instead came up with an idea about four female friends who get sucked into a video game, that would’ve been “the same but the same.” That’s how most writers think. Their ideas are only one degree different from the idea that inspired them. You need to go two or three degrees before you get into “same but different” territory.

13 year old Edwin from New Jersey has found solace from his father’s cancer bout in the video game, Lord of Etyrium. He plays all the time with his best friends Benji and Soo. But when Edwin’s father dies, Edwin becomes too violent within the game. He has his hulking character, Valor, kill a bunch of peaceful troglodytes. Or kick down the wall to one of the cities, exposing everyone to monsters and beasts.

After a while, Benji and Soo don’t like playing with him anymore. This sends Edwin even deeper into the game. Here, he continues Valor’s violent streak. That is until his mom screws up the game, accidentally killing Valor. A depressed Edwin is sitting around the next night when a mysterious person from online sends him a special file. Edwin opens it and Valor appears in front of him in his room! “What strange realm is this?” he asks. “It’s New Jersey,” Edwin answers.

Valor is determined to head out into New Jersey and kill as many people as possible. Why wouldn’t he? Edwin has instilled him with violence. Edwin does everything he can to calm Valor down. And that’s when he learns that Edwin is “the” Edwin – the god that controls him! Valor swears allegiance to Edwin, agreeing to help him with anything he needs. Edwin shrugs his shoulders and thinks… hmmm. And so off to school he goes to have Valor scare the shit out of some bullies. Valor even helps him tap into his masculinity and ask a girl out!

Unfortunately, the NSA gets word that a hulking barbarian man is running around New Jersey scaring the crap out of people. Which, it turns out, is just the latest in a series of strange things happening around the state. It turns out whoever sent Edwin that file sent it to other players as well. Valor is just one of several beasts wreaking havoc. With the NSA on his tail, Edwin must enlist the help of his former friends to find the porthole back to Etyrium so he can send Valor back before he’s killed!

There’s a fine line between what makes these concepts work and not work. When they don’t work, they seem so silly as to be ridiculous. When they do work, they can be magical. And Valor works.

The scene that convinced me this was a real script and not someone fudging their way through a fun concept, happened around the halfway point. Valor asks Edwin why he’s so depressed and Edwin confesses that his father recently died. Here’s Valor’s response…

Valor then convinces Edwin to go out into the street and perform this ritual. Of course, since Valor is socially clueless, he starts belting the ritual at the top of his lungs. Edwin, meanwhile, is begging him to go back inside. But Valor keeps yelling at him to participate. Which only makes Edwin more embarrassed. But Valor keeps pushing and pushing until Edwin joins in, gradually losing himself to the ritual and having a massive breakthrough/breakdown where he finally mourns the loss of his father.

It’s a wonderful scene for a few reasons. But the main one is the contrast. Whenever you’re writing a big scene, you’re always looking for contrast. If it’s a light scene, you’re looking to contrast it with darkness. If it’s a dark scene, you’re looking to contrast it with lightness. If Valor had stayed in Edwin’s room with him, patted him on the back, and told him his dad loved him, it would’ve been the worst scene you could’ve possibly written. It’s the fact that the writers contrasted the sadness of losing a father with this big goofy video game chant that makes the scene a winner.

The real winner of the script, though, is Valor himself. He’s really funny. He’s so dialed in to the world of Etyrium that virtually everything he says is hilarious. Like when Edwin wakes up one morning, Valor is mischievously holding the neighbor’s dog. Edwin asks him what he’s doing. “I was about to slay this feral hound as a blood sacrifice to you. We can use the remains for a morning stew!” He’s got about 50 lines like that.

The only problem I had with the script was that it didn’t establish a goal for the characters until too late. It would’ve been nice if they had some adventure to go on here on earth, at least to give the characters a goal. But the only thing driving the plot through the first half of the screenplay was the NSA chasing them, which didn’t have much impact because it took them too long to figure out where Valor was.

Eventually, we learn that the goal is to get Valor back to his world. But that goal shows up around page 75. We needed it a lot earlier. Still, I can see why Amazon bought this. It’s perfect Lord of the Rings adjacent programming (Amazon is spending 1 billion on a Lord of the Rings show). But even without that, there’s so much potential for a franchise here. You have so many directions to go with a sequel. I can already imagine tons of creatures from Etyrium entering our world, leading to a giant battle. Which would be expensive. But guess who has lots of money?

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[xx] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: On Deadline.com, this was the logline for Valor: “After a marauding warrior from a popular video game dies, he is reincarnated in our world and discovers the god he’s always worshipped turns out to be a 13-year-old Asian kid from New Jersey adjusting to life with a single parent.” You’ll notice that, in the opening logline I used, I eliminated “adjusting to life with a single parent.” Why? Because you want to end your logline with a BANG. Not a dragged-out whimper. The “bang” is the shock of the god being a 13 year old Asian boy from New Jersey. Every word you add after that weakens the logline. Nobody wants to read, “Superman is tasked with stopping a group of evil aliens hellbent on destroying our planet… and also some people in his life are starting to realize he’s Clark Kent.” Why would you ever include that last part? END YOUR LOGLINE WITH A BANG!!!!

Carson does feature screenplay consultations, TV Pilot Consultations, and logline consultations. Logline consultations go for $25 a piece or $40 for unlimited tweaking. You get a 1-10 rating, a 150-word evaluation, and a rewrite of the logline. They’re extremely popular so if you haven’t tried one out yet, I encourage you to give it a shot. If you’re interested in any consultation package, e-mail Carsonreeves1@gmail.com with the subject line: CONSULTATION. Don’t start writing a script or sending a script out blind. Let Scriptshadow help you get it in shape first!

Brian Duffield’s latest script asks the question, “Who needs dialogue?”

Genre: Horror/Sci-Fi

Premise: An exiled anxiety-ridden homebody must battle an alien who’s found its way into her home.

About: This is Brian Duffield’s latest script, which he will be directing. He’s got rising star Kaitlyn Dever (Booksmart, Unbelievable) starring in the title role. I don’t think I have to remind everyone of my love for Brian Duffield. He’s one of my favorite screenwriters!

Writer: Brian Duffield

Details: 90 pages

Will the writer with the most scripts ever to appear in my Top 25 add yet another script to the list? Let’s find out!

20-something Brynn lives all by herself in a house out in the woods. She spends her days buying those little holiday village buildings online and adding them to her growing little miniature town. She also likes to write letters to friends and dance by herself to music from the 30s on her record player. Yeah, Brynn doesn’t exactly live the FOMO life.

Brynn is also not well liked in town. Whenever she has to go into town to send her letters, we see people staring her down, giving her the evil eye. We’re not told why. But Brynn doesn’t have any friends around here. Which makes it sad when she visits her dead mother’s grave. Even there, people from other funeral processions stare.

One night, while Brynn is sleeping, she hears noise downstairs. When she goes to inspect the noise, she sees that it’s a gray alien. The alien spots her and begins chasing her around the house, climaxing in a face-off in the living room. Brynn takes one of the village buildings she collects and cracks it across the alien’s face, killing it instantly!

As soon as the alien dies, all the power, including the battery in her car, goes dead. It appears to have released some sort of EMPT bomb when it died. Brynn rides her bike to town the next morning to tell the police, but all of them stare at her coldly. Clearly, the police hate Brynn for some reason. By the way, there’s been no dialogue this entire movie so far.

Brynn decides that the only course of action is to leave town. But when she gets on the local bus, one of the passengers attacks her! Clearly, it is connected to the alien from her home somehow. The bus screeches to a stop and Brynn runs back to her town, having no choice but to go back home.

Once at the house, her worst fears come true. Aliens come back to pick up their own. These are much bigger, much scarier, aliens. And it takes every ounce of fight Brynn has left to elude them. But they eventually capture her. In our big final climactic moment, an alien places its finger on Brynn’s forehead, which sends us into a flashback of how Brynn ended up alone in this house, hated by the town. It acts as some sort of catharsis for Brynn, who, theoretically, can now move on with her life. But will she?

Let me show you what an average page of this screenplay looks like…

Brian Duffield may be the most minimalist screenwriter in Hollywood. Most of his action paragraphs in this script are one line. At most two. As a point of reference, I just got done with a screenplay consultation where I had to tell the writer he should probably scale back all the 8-line paragraphs.

Not enough writers think about the load of work they place on the reader. The more dense with text the pages are. The more characters there are in the story. The more plot there is. The more exposition that needs to be conveyed. All of these things factor into the workload you’re placing on the reader. The higher the workload, the better the script has to be because you’re making the reader work harder. And when the reader works harder, they want to be rewarded for that extra work.

That doesn’t mean every script should have two characters, a super-lean writing style, a thoughtless plot, and zero exposition. Writing a script like that has its own challenges, namely that ‘too simple’ can quickly become ‘too boring.’ All I’m saying is ‘workload’ is one of the factors you want to take into account before writing your script. Or choosing your concept. Because there is something to be said about making the reading experience easy.

Nobody understands that concept better than Duffield. I would even say that it was a key ingredient to his success. Nobody ever read a Brian Duffield script and said, “Man, that was such a long tedious read.” You may not have liked it, but it only took 60 minutes out of your life. Compare that to the post traumatic stress I’m still experiencing after the 4 hour battle I had with the “Mank” script.

As for the story itself, I have mixed feeling about No One Will Save You. I always wanted to keep reading. But I’m not sure I was satisfied with the payoff. In fact, I don’t know if I understood it. I’m going to reserve my thoughts about that to comments so that I don’t spoil anything here. If you understood the ending, head down to the comments so we can discuss.

My main issue with No One Will Save You is that 90% of it is running from one location to another. It may be from home to a bus stop. It may be from the kitchen to the living room. There’s only so much of “Brynn scurries behind the refrigerator” a reader can. It reminded me of one of my least favorite of Duffield’s scripts, The Babysitter, which also had the main character running around and hiding a lot.

Whenever I read an action script, which is essentially what this is, I’m looking for unique or stand-out set pieces. If you can come up with 4-5 inventive set pieces in a script like this, you can make a good movie. But if it’s all just running from one hiding spot to another, there’s no structure to that. Point A to Point B gets repetitive quickly.

No One Will Save You has one stand-out set piece, which occurs on the bus when Brynn is trying to escape town. The mailman (who was set up earlier as a creepy guy) ends up getting on the bus as well and we see him seated far back behind Brynn, who is unaware of his presence. As time goes on, we see him keep moving closer and closer to her, moving up from seat to seat. It’s super creepy and we’re screaming at Brynn to turn around. Of course, she doesn’t until it’s too late and he attacks her. That was a fun scene. But that was the only true set piece scene in the script. I wish there had been more.

I will say this was better than the similarly-themed “Trespasser” from a few weeks back. Much better. So there’s that.

Part of me reads a script like No One Can Save You and thinks, “This is a 45 minute movie.” Most scripts are around 20,000 words. This is maybe 12,000. Is that enough meat for a movie? I’m not convinced it is.

However, the other option is that Brian Duffield understands this generation better than the rest of us. He knows that nobody has time. He knows that everybody has options. So he writes in a way that’s quickly digested. And his movies move in a way that allow them to be consumed quickly. Should we be resisting this style or should we be following his lead?

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: There is no dialogue in this movie. There’s no doubt that this had a huge influence on why Duffield chose to convey the action via extreme minimalism. There’s no way to make a reader angrier than a script with little-to-no dialogue and BIG CHUNKY DESCRIPTION PARAGRAPHS. That’s every reader’s worst nightmare. Dialogue is the fastest part of the script to read. When you eliminate it, it takes three times as long to read the screenplay. Duffield identified that issue and curtailed the action lines so that the script still read fast. Smart move on his part.

A little while back, I was reading a murder-mystery consultation script. The opening scene covered the murder our detectives would spend the next 100 pages trying to solve.

Teaser scenes tell me a lot about a writer. Their construction is such that you can have a lot of fun with them, almost make them into a mini-movie. So if a writer can’t entertain me with their teaser, there’s a good chance they can’t entertain me for the next hour and a half.

Anyway, this murder scene takes place in a dorm room (I’m adjusting the actual details in order to keep the plot private). A stalker sneaks into the dormitory, makes his way up to his target’s room, and tricks her into opening the door. The rest of the scene takes place over one page and consists of the girl struggling a little bit but the killer easily subduing and, eventually, stabbing her to death.

The scene was extremely boring to read and I asked myself, “Why?” Technically, something exciting was happening. A girl was getting attacked. She was fighting for her life. And in the end, she sadly gets murdered. In what scenario is a murder “boring?”

The answer to this question is complicated but I’ll try and simplify it for you. In the real world, a murder is anything but boring. In a movie, however, people get murdered all the time. And because they’re fictional, the audience isn’t fazed by their death. So, in the context of storytelling, a murder can be just as boring as two characters talking at a diner.

But why was *this* scene so boring?

I had to keep reading the script before I noticed a pattern that ultimately identified the problem.

Anybody here a fan of Gwen Stefani’s old band, “No Doubt?”

That was the problem.

There was NO DOUBT within this opening murder scene that the murderer would succeed. There was never once where the girl got the upper hand. Or tried to talk the murderer out of it. The scene was a foregone conclusion. And foregone conclusions in the medium of storytelling are the equivalent of death. There is nothing that brings on boredom faster than a foregone conclusion.

I want you to imagine a see-saw. On one end of the see-saw is DOUBT. On the other end of the see-saw is CERTAINTY. Now I want you to imagine each one of your script’s 50 scenes as a person. Every time you write a scene where the outcome is certain, you are adding a person to the “Certainty” side of the see-saw. Before long, you’re going to have twenty people sitting on the Certainty side and, by sheer accident, one or two on the Doubt side.

How do you think a script like that reads? I’ll give you a hint because I read all these scripts. IT READS BORING.

Now it just so happens that I’ve been coming across a lot of suggestions to check out the old murder-mystery show, “Columbo.” I’d never seen Columbo before. Something about it put me off though I could never identify what. But I’m always willing to give something a shot.

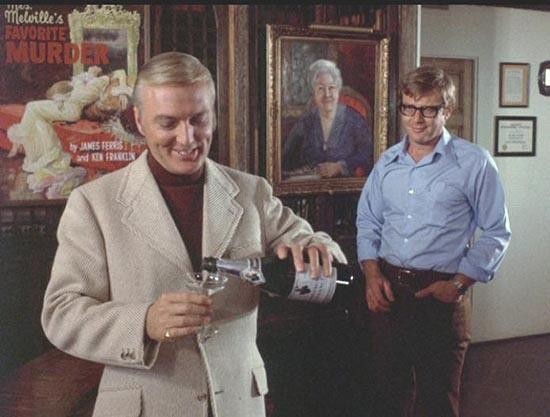

So I watched the second episode (due to some confusion, I thought it was the pilot). By the way, before I get to the analysis, I suggest all of you check it out. The story is about writers who live in Los Angeles so there’s plenty of familiar territory to appreciate. And it was directed by Steven Spielberg!

‘Murder by the Book’ introduces us to Jim Ferris, one half of a successful murder-mystery writing team. Jim is up on the 30th floor of his Century City office all alone for the weekend doing some writing. There’s a knock on the door.

He goes to open it and his co-writer, Ken Franklin, is standing there with a gun pointed at him. At this moment, we know what’s going to happen. These two are a writing team that are coming to an end. Ken wants all the money for himself so he’s going to kill his partner. It’s as certain as certain can get.

But then, oddly, Jim smiles. “Nice try,” he says. “What?” Ken replies. “You wouldn’t kill me with that gun. You’re not wearing gloves. Your fingerprints would be all over it. We’re murder-mystery writers. We know this stuff.” Ken smiles and lowers the gun. “You got me,” he says, and proceeds to walk past Jim into the office.

Notice what’s transpired. We were certain something was going to happen. Ken was going to kill Jim right there. But it turns out we were wrong. Ken was just playing around. The writer of this episode, Steven Bocho, had now injected some DOUBT into the scene.

Ken is still going to kill Jim though, right? We don’t have a procedural if there’s no murder. But even after Jim closes the door, Ken seems to relax. Is he going to kill him? (DOUBT). We learn a little more about the situation. The two are splitting up. Jim, it turns out, wants to move away from mystery writing and take on more serious subject matter.

Still, even though it seems like Ken is up to something, we’re not clear what his plan is. There are several moments he could kill Jim in the office yet he doesn’t (DOUBT). Ken eventually makes a pitch that they drive down to his house in San Diego and celebrate their big split with some champagne and good conversations. Reminisce about all the good times they had.

Jim is a little reluctant but eventually concedes. The two walk down to Ken’s car, which is all alone in the parking lot. But when they get inside, Ken “remembers” that he left his lighter up in the office. “I’ll be right back,” he says. I was absolutely certain that the second Ken was twenty steps clear of that car, it was going to blow up.

But it didn’t. Even more DOUBT.

At this point I was so curious how and where this murder was going to happen that I was hooked. I’d reached that point in a show or movie where you stop analyzing and start enjoying. And I can confirm to you that the primary reason for that was the level of doubt Bocho and Spielberg infused into the scene.

You see, most writers think of scenes as a sprint. Get from Point A to Point B as quick as possible. Good writers think of scenes AS A DANCE. And DOUBT is like a good set of dance shoes. It really allows you to get jiggy with a scene (or an entire narrative).

I was doubting how Ken was going to kill Jim ALL THE WAY UP TO, literally, the second the murder happened. That was how well-constructed the doubt was. And, by the way, this is from an episode of television 50 YEARS AGO. Think about that for a second. This writer was able to fool a viewer after 50+ years of similar content, much of which was inspired by this show.

That should tell you just how valuable the tool of DOUBT is in storytelling. It doesn’t matter how seasoned the viewer is. With some carefully placed moments of doubt, you can stay ahead of any viewer.

Some of you may say, “Well, sure, Carson. If I had 15 minutes to write an opening murder scene, I could create plenty of doubt too.” Which is a valid point. But you don’t need tons of time to create doubt. All you’re looking for is to make the viewer think the scene could go one of two ways. That doesn’t take much. It could take one moment that creates doubt.

Let’s go back to that opening consultation scene. What could we have done to create doubt? Well, the college girl is the potential victim here. So what you want to do is give us at least one moment where we think she’s going to escape. For example, the killer gets inside her room, corners her, and there’s a scuffle. It’s intense. She’s fighting hard. She somehow manages to stun him enough to get around him and run for the door.

Just as she grabs the doorknob, though, she’s dragged back. Even that moment – right up until she’s grabbed – is going to give the reader hope that she might get away. In other words, they’re doubting that the murderer will succeed. And if you really want to have fun, take the character as close to escape as you can before ripping it away.

For example, maybe she gets away A SECOND TIME and this time she DOES open the door. And she DOES run down the hallway. But it’s winter break. She’s the only one on the floor. So she’s screaming for help but nobody’s around. The killer is able to catch her again and murder her right there in the hallway.

How much more exciting is that scene than the killer easily walking through her door and easily killing her in her room? Way more entertaining right? That’s the power of DOUBT. Let it become a major part to your writing.

Today’s script is one of the darkest dramas I’ve ever read.

Genre: Drama

Premise: (from Black List) A Black amateur bodybuilder struggles to find human connection in this exploration of celebrity and violence.

About: Elijah Bynum got a couple of great actors to act in his debut film, Hot Summer Nights: Maika Monroe and Timothee Chalamet. This looks to be his next film. It finished with 9 votes on last year’s Black List.

Writer: Elijah Bynum

Details: 84 pages

I’m not going to lie.

It’s becoming harder and harder to open Black List scripts these days with any level of optimism. Back in the early Black List days, you had bad scripts. But something has changed recently in the list’s process that has resulted in a lot more bad scripts than there has ever been before.

But I’m not phased by it.

To me, writing a good screenplay is one of the hardest things in the world to do. I honestly believe that. So when anyone writes something good, I consider that a rare and major accomplishment.

This begs the question, how do you write something good?

There’s no one way to answer that question, of course. But, in my experience, it starts with an interesting character. Not an interesting concept (although that’s important). But the priority should be a compelling main character.

I know that’s controversial to say. But think about it. If you create an interesting character – somebody like Cassandra in Promising Young Woman or Louis Bloom in Nightcrawler or Arthur Fleck in Joker – they’re usually in EVERY SINGLE SCENE. Which means that, if we’re operating by the rule of transference, every single scene will have something interesting in it.

Meanwhile, a good concept will provide you with some good scenes. But once the second act rolls around and the concept isn’t as dominant, you’re going to need a compelling character to keep our interest.

Then, once you have that interesting main character, it’s about coming up with a plot that moves the narrative along quickly. By “quickly” I mean relative to the character’s situation. Quickly might mean within the next 90 minutes if you’re writing “Gravity.” And it might mean within the next two weeks if you’re writing “Joker.”

From there, it’s about taking a couple of risky choices in your story and staying ahead of the reader. So if you’re writing a movie about a heist, you want to make a choice that nobody’s ever seen in a heist film before. It should be something daring that scares you a little bit. The reason something is memorable is because it’s different. Nobody remembers things that are the same.

And when you’re writing in the small plot developments that occur throughout the story, you want some of them to be expected (so the audience thinks they know where the story is going), but more plot developments that they don’t expect (so they’re continually surprised). I remember watching the first 20 minutes of Parasite and thinking, “Okay, this is going to be about a guy who becomes a math tutor for a rich family and an inappropriate relationship is going to develop between him and the daughter. Seen this movie before.” But the plot unexpectedly has the tutor bring his sister into the fold under false pretenses (as an art tutor for the little boy). That’s when I thought, “Hmm…I wonder where this is going.”

Finally, you need some je ne sais quoi lightning-in-a-bottle x-factor that elevates your script above the others. For most writers who achieve this feat, it’s their unique voice. But it could also be a crazy twist that nobody’s ever seen before (The Sixth Sense). It could be an idea that’s directly in line with the zeitgeist at the moment, like Get Out. And it could be a killer concept. I’m not talking a B+ concept. I’m not even talking an A concept. I’m talking an A+ concept, like A Quiet Place.

Today’s script seems to embrace that primary idea of creating a memorable character. Let’s see if it succeeds.

Killian Maddox is a 30 year-old bodybuilder. And when I say “bodybuilder,” I mean “BODYBUILDER.” Killian spends all his free time in the gym. He only eats chicken, eggs, broccoli and rice. He abuses every steroid known to man. And he doesn’t have any friends. To do so would stand in the way of his dream – to place at Nationals.

But even Killian, as anti-social as he is, needs companionship. He’s been scouting out one of his coworkers at the supermarket. Her name is Jessie and she’s one of the only people who treats him with kindness. One day he gets up the courage to give her his number. “If you want to go out sometime, call me,” he says, before running away.

Meanwhile, Killian’s just learned that the painting service his grandfather used to paint his house did a terrible job. The house needs another coat. So Killian calls them to tell them so. They respond by telling him to fuck off. Word to the wise, painting people. Don’t piss off someone with nuclear roid rage. Killian speeds over to their store after hours and trashes the entire place.

Killian eventually goes out on that date with Jessie and we get the script’s best scene. Killian is so unfamiliar with social situations that within two minutes, he casually tells Jessie that his mom and dad are dead. He shot her in the head when Killian was 13. And then shot himself. But that’s not even the part that scares Jessie. It’s what he orders.

Killian: I’ll have the sirloin. Eight ounce. Medium rare. With just the broccoli. No fries. No butter. And…also…the Cedar Grilled Lemon Chicken please. And the Southwestern Steak Salad… Hold the cheese and tortilla strips. Dressing on the side please. And does the maple mustard glaze on the salmon contain sugar?

Waitress: I’m actually not sure… I can check.

Killian: That’s okay. I’m sure it does. I’ll take the salmon, too. You can just hold the glaze.

Waitress: … okay… will that be it?

Killian: Would you be able to do a side of chicken breast? Just chicken breast, grilled, nothing else on it?

Waitress: Yes. Sure. We can do that.

Killian: And a diet coke please.

It’s at that point where Jessie realizes she’s on a date with a psychopath and excuses herself to go to the bathroom. None of us are surprised when she doesn’t come back. But Killian is. And you can only imagine what this does to him. It enrages him. It makes him want to work harder. Lift more. Get bigger. He’s going to show everyone once the Nationals come around.

The hardest scene to read is when Killian has a heart attack. He’s rushed to the hospital where the doctor informs him that all of his organs are operating like that of an 80 year old man. They need to do surgery immediately if he’s going to make it even another two months. But Killian refuses the surgery. Why? Cause it will create scars. And bodybuilders can’t have scars.

Killian’s life continues to deteriorate when the paint guys come back for their revenge, he loses his job, and his grandfather dies. Now there is nothing left but to get bigger, get stronger, place at Nationals, and finally achieve his dream, to be on the cover of a magazine. Will he do it before his body gives out? We’ll see…

The thing that Magazine Dreams gets right is the first thing I mentioned above – an interesting character. Whatever you feel about this script, you have to admit that you’re always turning the page to see what Killian will do next.

But the extremes to which the writer goes to create this character come at a cost. At a certain point, things get too dark. They get too depressing. So even though you’re compelled by Killian, the story has disintegrated into world-class sadness. It’s too much.

A big screenwriting tip writers are encouraged to follow is “make things hard on your hero.” And after you’ve made things hard on your hero, make things harder on your hero. This is how you test your character. But Magazine Dreams shows us what happens when you take a piece of advice too far. Dead Grandpa. A date that ditches you. Guys beat you to within an inch of your life. Heart attack. Lost your dog.

At some point it’s like, “Come on.” Even Arthur Fleck had some nice moments, such as when he went on several dates with his neighbor. I know I know. It wasn’t real. But we didn’t know that at the time. The point of the scenes was to add balance to Joker specifically so it didn’t feel like Magazine Dreams – where every single step is a fall.

We’ve been talking about “situations” this past week. It’s not surprising that this script’s best scene is a situation. It’s the first date dinner between Killian and Jessie. We know how awkward Killian is but we’re desperate for him not to fuck this up. This is the one person on the planet who likes him. If he loses her, he’s got nothing. So we’re really rooting for him to figure this out. And when he blows it, it’s hard to watch, but captivating at the same time. Everybody has to look when passing the 5 car pile-up. We can’t help ourselves.

I recommend this script because of its fascinating main character. But it gets way too dark. And the ending, like a lot of endings in character pieces that don’t have a solid plot foundation, is unsure of where to go, and that ends a really captivating character’s journey with a whimper. We needed an ending that was consistent with how interesting this character was.

So I’d definitely check this out if you’re into dark stuff. It itches that scratch. But be careful, you might scratch so hard that it leaves a scar.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Many memorable characters push against the edge of darkness. If you look at the three I mentioned earlier – Promising Young Woman, Nightcrawler, Joker – all of those characters are pushing the limits of what’s acceptable in society. And that’s a primary ingredient for what makes them memorable. But the difference between those characters and Killian is that they had lightness too. Even Arthur. He wanted a girlfriend. He wanted to be a stand-up comic. The whole point of pushing someone up against the darkness is giving them the choice to go back to the light. And all of the light was snuffed out in Magazine Dreams by the 20 page mark. There aren’t many people who can handle that.

What I learned 2: Squirrel away plot developments. Bynum does something really clever with the romantic subplot. He has Killian ask Jessie out. However, he has other stuff going on in the story at the time. He doesn’t need them to go out on a date right away. So what he does is “squirrel away” the plot development for later. He has Killian give Jessie his number and say, “Call me if you want to go out.” This way, when the plot gets thin 20 pages down the line, he has a plot development squirreled away he can use. Jessie calls Killian and asks if he’s still up for that date.

As you continue to battle through the rewrite of your AMATEUR COMEDY SHOWDOWN script, I thought to myself, how can I help these writers make their script funnier? That got me thinking about yesterday’s script review and the concept of SITUATIONS. Here’s how I defined situations in that review…

A situation, in screenwriting terms, is a familiar event, with genuine consequences, where the reader understands the rules and can, therefore, participate in the fun.

A bank robbery is a situation. A breakup is a situation. A battle of wits, such as when the Man in Black took on Vizzini in The Princess Bride – that’s a situation.

The great thing about comedy is that comedy and situations go together like peanut butter and jelly. So that’s what we’re going to do today. We’re going to add one “Situation” scene to your comedy. And we’re going to make it hilarious.

So what I’m going to do is list ten situations for you and you’re going to choose which one of those would fit best in your script and write the funniest version of that situation that you can think of.

Here’s your list:

1) A breakup – Breakups are some of the easiest scenes to make funny. They’re inherently comedic. A word of advice, though. Be creative about where they take place. For example, it’s probably funnier to have someone break up with their boyfriend at the beginning of a flight than in their car. Add a guy who’s terrified of flying and you’ve got yourself a scene.

2) Underage kids trying to buy beer (or get into a club) – We’ve seen this situation a million times before yet audiences will watch it a million times more. There’s something about watching underaged kids try to pull one over on the cashier/bouncer that never gets old.

3) Job interview – Job interviews are packed with tension and you can find a ton of comedy in tension. They can also pop up in unexpected places. One of the funnier scenes in Deadpool 2 was the job interview sequence. Step-Brothers also has a good one.

4) Meeting the parents – The first time someone introduces their boyfriend or girlfriend to their parents is a situation. Try to create clear boundaries to make the scene better. For example, if you force them to sit through dinner at a restaurant, that creates more tension than if they come over to the parents’ house, say hi, and everybody goes their own way. Remember that the more boundaries and rules that are in place, the better a situation works.

5) A dreaded gym class game – Those gym class games, from basketball to soccer to dodgeball, are inherently funny because we’ve all been through them and know the rules. You have to go through the torturous process of getting picked. Then you have to play a game you suck at. You always come out looking bad. Before you say this is too specific since it only covers school years, remember that they made an entire film about adults in this situation (Dodgeball). If you’ve got a workplace movie, maybe it’s a game they play during a retreat.

6) The big boardroom presentation – These work best when your hero is the presenter and there’s a ton of pressure on them to do well. But you don’t have to write them that way. You can have your hero be a nobody in the boardroom but be unexpectedly called upon to offer his opinion. He can then fail spectacularly.

7) The hustle – The hustle is a great situation. Whether it’s pool, chess, or basketball, you establish that someone is going to be hustling someone else and then watch the game unfold. Always entertaining, especially if you flip the script (and the ‘hustled’ is the real ‘hustler’).

8) Stuck in line at the DMV – The never-ending torture that is being stuck at the DMV – in endless lines, talking to people who aren’t helpful, forgetting documents you were supposed to bring, being forced into a surprise driving test (another situation!). Lots of hilarity here. Zootopia uses this one.

9) Walk of shame – Waking up in an unfamiliar bed with someone you don’t know and having no idea how far away from home you are and how you’re going to get back is an age-old situation that offers all sorts of comedic possibilities. The more obstacles you can throw at the character, the better.

10) Getting pulled over by a cop – Always a fun situation to play with because we’ve all been there, understand the rules, and there’s a clear goal to the proceedings (try not to get a ticket!). The more your character has done wrong, the better, since they’ll have more to hide.

The above are general situation templates but there are tons of situations specific to whatever subject matter you’re writing about. People stuck in a shack in the woods with zombies trying to get in through every window – that’s a situation. Being inside a convenience store when men come in to rob the place, that’s a situation. A guy standing on top of a building, deciding whether to jump or not with a bunch of people trying to stop him – that’s a situation.

You’ll notice that the higher the consequences of a situation, the more interesting the scene tends to be. So if you have someone who’s standing on top of a building ready to jump… that’s a very high-consequence situation. The Office had a famous one of these where Michael fakes like he’s going to jump off the building so that his employees will appreciate him more but then, the more he talks to everyone, the more he *actually* wants to jump, which turns it into an increasingly serious situation.

By the way, what *isn’t* a situation? Situations dissolve whenever the boundaries become faded and the rules less clear. For example, a wedding ceremony is a situation. There’s a clear beginning, middle, and end, with high stakes attached to it (since usually, in movies, somebody’s going to try to stop the wedding). But a wedding post-party is not a situation. It’s just a vague chunk of time dedicated to people having fun. There are no rules. There is no clear climax. That doesn’t mean funny things can’t happen during it. But whenever something has less rules and less structure, the tendency for it to become unfocused and boring increases.

Actually, whenever you’re in non-situation territory, like a wedding after party, I encourage you to add as many of your own rules as possible, to create an “artificial situation.” For example, if Best Man Joe is trying to win the heart of Maid of Honor Jane, maybe his goal is to profess his love for her at the after party. Now the after party has structure (since there’s a goal and, therefore, something to look forward to) which makes it an artificial situation.

Finally, situations work best when they’re used within concepts where you wouldn’t expect them. For example, you don’t expect a trip to the DMV to be in the movie Zootopia. Or if you’re writing a Star Trek parody, throwing in a walk of shame scene could be a really unexpected way to have some fun in that universe. You want to look for ways to flip the script. For example, instead of following a group of teenagers who are trying to sneak into the club with fake IDs, maybe your movie is about a group of adults who, at some point, find themselves trying to sneak into a kids party where they have to pretend they’re under 18. In other words, you never want to execute situations exactly as expected. You want to look for little twists and turns to make them fresh. One of the best examples of this came from Notting Hill where we get the situation of a ‘FIRST DATE.’ Hugh Grant shows up for that first date and finds himself in the middle of a publicity tour.

Situations are great for any genre but they can be really fun to play with in comedies. So have at it!