Search Results for: F word

Genre: Sci-Fi/Drama

Premise: A lone researcher at a remote Arctic station waits to die after a cataclysmic planet-wide event kills everyone. But plans change when he finds an 8 year old girl hiding within the base.

About: This is a big project that came together a couple of years ago when George Clooney (who will play the lead) purchased the rights to the relatively unknown 2016 novel. He hired Mark L. Smith (The Revenant) to write the screenplay. Netflix won the rights to the project.

Writer: Mark L Smith (based on the novel by Lily Brooks-Dalton)

Details: 111 pages

It’s going to be an interesting review today. For starters, I love Mark L. Smith. I think he’s a great writer. There are a lot of writers out there who’ve got Hollywood fooled. They may have been given more credit than was due for a certain script (because some other writer came in and saved them) and have been living off that lie ever since. Smith is one of those guys who you know is going to deliver on whatever potential the concept has.

On the other hand, you have George Clooney. Clooney has some of the worst taste in Hollywood. The guy is consistently involved in terrible ideas and terrible projects. I mean let’s look at his last five major projects. Catch-22. Money Monster. Hail, Caesar. Tomorrowland. The Monuments Men. It’s pretty hard to be of George Clooney’s caliber and miss this badly this consistently. Remember, the guys at the top get pitched all the best projects. It’s not like he’s Stephen Dorff who doesn’t get to sniff a project until after it’s been turned down by 70 actors. Clooney gets the pick of the litter and still screws it up.

For that reason, I have no idea what to expect. I like when sci-fi delves into dramatic places IN THEORY. But as I’ll talk about in today’s “What I Learned,” it’s a dangerous sandbox to play in.

70 year old Augustine resides at a large Arctic base that is currently being cleared out. People are running over to a fleet of helicopters that are taking them home. We learn that an awful cataclysmic “event” has just happened on the planet and people want to get back to their families, even if it’s just to spend a few final days with them.

But not Augustine! The crotchety old man is taking it easy, Mr. Cheesy, staying up here all by his lonesome. Of course, it helps that he doesn’t have any family and that he’s infected with late-stage cancer. So why bother, right? Up here he can hang out in safety until he dies, probably outlasting everyone on the planet. The irony!

But right after everyone leaves, Augustine finds a little girl hiding in one of the closets. In all the madness, she was forgotten. Augustine is furious because this is not a situation where they can send someone back to pick her up. She’s stuck up here with him. And, oh yeah, the girl never talks.

Meanwhile, we cut to a spaceship called Aether, which is coming back from its failed mission, a mission that Augustine himself created. He thought he found a livable exo-planet right here in our solar system – a previously unknown moon orbiting Jupiter. So the Aether team went out there to see if we could live on it. Long story short: We can’t. And now the crew of Aether is confused because for the last 97 hours, they haven’t been able to make contact with earth.

Cut back to Augustine and the girl (who he’s named “Iris”). Augustine is getting readings that the unsafe air from the “event” has made its way up here. If they’re going to survive, they’ll have to head north to the big station. So they pack up, get on a snowmobile, and away they go. Of course, not everything goes according to plan. And Augustine begins to realize that while he may not be able to save himself and Iris, he can save the crew on Aether. Maybe.

You know the big voice guy at the beginning of every boxing fight? The guy that screams at the top of his lungs, “Let’s get ready to rummmmmmbblllllle.”

Well, imagine that guy is standing next to you as you open this script. But instead of that, he screams, “Let’s get ready to voluntarily go into a depression cooooooomaaaaaa!”

Man this was a depressing read.

Depressing depressing depressing. Oh, and more depressing.

I guess the positive way to pitch this movie would be: “The Road but in the Arctic.” I know a lot of people love that book and some even love the movie.

But here’s my issue with Good Morning – movies without hope are pointless to me. Stories that exist only to make you feel sad or depressed… I don’t get them. I guess there’s the occasional exception. Maybe if it’s a true story chronicling an important moment in history. But if you’re smart, even those movies should have a tinge of hope built into the end.

This doesn’t mean you can’t have depressing things happen in your movie. All good movies have elements of sadness or heartbreak or pain or depression. It’s when those things become the point of the movie and the main emotion the audience is left with that it becomes an issue. At least for me.

All of the plot elements in Good Morning Midnight are working against a good story. You’ve got earth, which has just been incinerated and 7 billion people are dead. Cut over to Augustine, who’s got terminal cancer, coughing blood into napkins every ten minutes. We’ve got this ship heading back to earth with all these astronauts who don’t yet know what we’ve already figured out. They’re flying corpses. And the more we get to know those astronauts, the sadder their lives are (one astronaut tells us their child drowned when they were 3 years old! – yes, we even get a dead child backstory thrown into the mix).

I mean give me one smile at least?

The one dramatic component that gives the story energy is the girl. Because, before her, this dude’s only purpose was to die. But now that there’s a girl involved, Augustine dying means she’s on her own. So there’s a bit of interest in seeing how Augustine is going to deal with that.

[major spoiler]

The problem is, everything about the girl is so suspicious that we know the writer’s up to something. Never saying a word protects the girl from having to be a “real” character, which turns out to be the point. She isn’t a real character. She was a figment of Augustine’s imagination. And because we always knew something was up, the biggest surprise in the script isn’t much of a surprise.

I’d be interested to know if the book kept the characters at the first Arctic station the whole time. I’m guessing it did. But Smith is such a good writer that he knew keeping them at that station was script suicide. To not only base your story around billions of dead people and a handful of soon-to-be-dead people – but, in addition to that – having your main characters, one of whom doesn’t even speak, waiting around inside a base for 120 minutes. I’ve seen traffic signs with more uplifting storylines. At least with those you see a person walking across the road. You know he’s going to get there as long as you don’t hit him.

So the stuff where they’re “on the road” is the best stuff in the script. I liked the wolves. I liked the ice cracking, cutting them off from their vehicle and forcing them to walk the rest of the way. That’s the only time where the story had momentum.

As for the spaceship, I struggled to figure out why we were following Aether other than it gave us the occasional break from Grandpa Depressing and Little Margie Mute. There is an almost-there twist involving the ship that could probably work with a few more drafts. But that twist was the only value brought from the ship storyline. Otherwise it was five people talking about how much of a bummer it was that everyone they knew was probably dead.

So I have a question for the readership here because I felt the exact same way after watching The Road. I thought that was the world’s most depressing boring movie ever. Everyone I talked to would point me to the book. “Read the book! It’s so much better!” So I’ve tried to read the book five times now and each time I can barely get through a few pages without being depressed out of my mind.

My question is, for people who like this stuff, why do you like it? Why do you like to watch movies (or read books) that make you feel depressed and hopeless? Cause maybe this is a good novel, just like a lot of people thought The Road was a good novel, and I just don’t get this stuff. It’s not my thing. However, I’d love to learn why it works for others.

Couldn’t get into this one, guys. :(

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Sci-fi and Drama is a friendship that’s hard to make work. It can succeed, yes. But sci-fi fans like the imagination and the fun places you can go within science-fiction concepts. The heaviness of drama often works to neutralize those fun components. Look at Ad Astra, another sci-fi drama. The two best moments in that film were the opening space elevator accident and the moon buggy chase. Exciting imaginative science-fiction scenes. Everything else was pretty freaking boring. And I suspect it had to do with the drama constantly neutralizing the fun stuff.

The big announcement for the next Amateur Showdown is here. And it comes with a twist!! A true GAME-CHANGER!!!

This is a quick reminder that NEXT THURSDAY by 8pm Pacific Time, your Character Piece Showdown entry needs to be in! If you’re going to enter, send me your title, logline, genre, why we should read your script, and a PDF of the screenplay to carsonreeves3@gmail.com.

But now, it’s time for the announcement you’ve all been waiting for.

The next Amateur Showdown genre.

What will it be? Any ideas?

Here’s a clue. Entries need to be received by Thursday, October 15th, 8pm Pacific Time.

That is right, my friends. It’s happening in the month of October. And that can only mean one thing.

Time for the Official Announcement Cue

**ANNOUNCEMENT** **ANNOUNCEMENT** **ANNOUNCEMENT**

The next Amateur Showdown will be……. Horror Showdown.

I’m assuming all of you are dancing in your living rooms, calling your friends, busting out that Joseph Phelps Insignia 2016 wine you’ve been saving for the perfect occasion. I’m sure the media will go crazy once they get a hold of this info so who knows how many entries we’re going to receive. Is tens of thousands out of the realm of possibility?

BUT WAIT! THERE’S A TWIST!!!

Wait, what Carson? Are you trying to give us a heart attack?? How can you add anything more exciting than this?

Are you ready for the twist?

I don’t think you’re ready.

Maybe I should just cancel the twist.

Just kidding!

TWIST: You can submit either a horror screenplay or A HORROR SHORT STORY.

That’s right.

We can’t ignore reality anymore. Short horror stories are getting bought up for 7 figures routinely. So why not jump on that bandwagon?

I know some of you are going to hate this. I can actually see the hate flowing through the internet into my computer screen right now. It has arrived in the form of the ‘Update Now?’ pop-up alert that only allows me to delay the return of said alert for 1 day. I’m sorry, though. The bus has left the station. It’s too late to stop it.

Here’s why this will be fun. A script is 24,000 words. A short story can be 2000 words. It can be 1000 words. That means anyone here can get something written by the deadline. Which means we should have more competition. And more competition leads to a better winner. Game on, my friends.

Same entry process. Send me your title, logline, genre (horror or horror adjacent), why we should read your script/story, and a PDF of the screenplay/story to carsonreeves3@gmail.com any time before Thursday, October 15th, 8pm Pacific Time.

If you want to know how to write a good short story, I’m sure many of you will have suggestions in the comments for what to read. I’m actually interested in hearing about some good short story destinations myself. If you want to get started, buy any of Stephen King’s short story collections. He’s the best.

Outside of that, have fun.

I think this is going to be a blast. You’ve got two months. Time to get started!

Genre: Sci-Fi

Premise: In a dystopian society, a government worker recovering from a traumatic accident is rescued by a group of rebels who insist that he’s the leader of their movement.

About: I have to give it to Mattson Tomlin. He’s been scrapping away for a while, occasionally getting scripts on the Black List. I’ve reviewed a couple of his scripts before, a Jason Bourne parody script and a different sci-fi entry. I didn’t dislike either script. But neither one had that extra something that puts a script over the top. Well, apparently, Warner Brothers doesn’t agree with me. As they gave Mattson the most coveted job in town – the latest Batman movie that Matthew Reeves is making. I’m not sure if he dropped 2084 before or after he got this job, but I’m assuming just the mention of him being up for the job helped Paramount snatch up 2084. I heard it was pitched as 1984 by way of The Matrix and Inception. That is a lofty pitch! Let’s see if the script lives up to the hype.

Writer: Mattson Tomlin

Details: 116 pages

You guys know me!

There isn’t a big sci-fi spec I won’t read.

So when I heard Mattson Tomlin was taking on one of the granddaddies of sci-fi literature, writing an unofficial 100-years-later spiritual sequel to 1984, I needed to get my hands on it. Especially since Tomlin’s screenwriting star is rising quickly.

Question to the class before we get started. Has anybody here read 1984 cover to cover? I feel like we’ve all STARTED to read it. But I’m not sure anyone’s ever finished it. Extra points for those of you who did so on your own and not because your high school English teacher told you to.

Malcom Ferrel doesn’t know what’s going on. He’s just woken up in a dentist-type chair. A dude with a Hazmut suit is standing over him. He’s asking Malcom what his name is and if he remembers his “trauma” or not. Malcom does not remember his trauma. Good. Then we can get you back into society, the guy says.

Malcom enters suburbia, which looks like the 1950s for some reason. Except for the fact that everybody has to wear an elaborate super suit that protects them from the air. It’s like Covid on steroids I guess. Malcom is told by his driver that he works for the government and to stop trying to remember the trauma he experienced. It’s better if he moves on.

Once he gets home, there’s a party going on in the backyard, and then WAM BAM POW a van smashes through the fence. A bunch of black clad SWAT like dudes bust out and start slaughtering everyone. Malcom’s buddy Stan confirms to home base that he has “the package” and the next thing we know… Malcom wakes up in the chair again where he must start the process all over again.

This time, he goes to meet with his wife, who, like the last batch of people, tell him to stop thinking of his past trauma. It will only make things worse. Then those SWAT DUDES show up AGAIN and there’s a firefight between the people protecting Malcom and the people trying to steal him. The SWAT guys finally get him, escape, and take him back to a secret base.

At the base, Malcom meets his real wife, Rachel, who informs him that he used to work for the government until he started this rebellion. But the government then stole him back, erased his memories, and tried to reintegrate him back into society. But they kidnapped him back. And then the government kidnapped him back. And then they kidnapped him back. And sometimes, if they can’t get him, they kidnap HER. Which is what happens next!

The government BUSTS into the underground base and while Malcom escapes, they get Rachel. We now follow Rachel in the dentist chair. Her memory has been erased. And we follow her as she’s cluelessly integrated into society. She even marries a dude. Will Malcom come save her. That’s their thing, Rachel told him back at the base. They always save each other. So now Malcom, who still isn’t even sure who he is, must save a woman he sort of is maybe sure is his wife.

I’m not going to beat around the bush. This didn’t work for me.

The number one thing you have to get right when you’re writing a big sci-fi script is sell the mythology. If we don’t buy the rules or the backstory or how your characters interact with this world, nothing else matters because we’re going to be so focused on how weak the framework is. 1950s town? Protection suits? Trauma elimination? There was something incohesive about the variables.

The idea of changing the main character and creating a dramatically ironic situation in that we know Rachel is being tricked but she doesn’t isn’t a bad choice on an idea level. The problem is that we got to know Rachel for two seconds before she’s thrust into this situation. So we don’t care about her. Or, at least, I didn’t. And, to be honest, I never got the best feel for Malcom either. Nothing we learned about him was real remember. It’s a bunch of fake memories taped over fake memories. In other words, even the person we’re hoping will save our damsel in distress is someone we don’t know. So we’re cheering on someone we don’t know to save someone else we don’t know.

That’s not how writing works.

You have to establish strong characters who we care about before you toss them into the mixer that is their screenplay journey. Both Neo in The Matrix and the character Leonardo DiCaprio plays in Inception have extensive introductions where we get to know the characters well before the shit hits the fan.

This does lead to an interesting screenwriting debate, which is that I always tell you to hook the reader right away. Make something happen immediately. Grab us and don’t let us go. Tomlin does that more than any of the scripts I’ve read so far in The Last Great Screenplay Contest. So then what’s the deal? The guy does what you say, Carson, and you’re still complaining?

Well, here’s the catch – and this is why screenwriting is so difficult – if you’re telling your story in a way where we’re meeting your characters “in media res,” you need to figure out quick ways to help us identify with them and like them. Your “save the cat” moments need to be lightning quick. Your glimpses into their humanity and what makes them sympathetic and empathetic need to be tightly executed.

This is where the best writers make their money. They can get you to fall in love with a character in ten lines. Good Time, the Safdie Bros movie they made before Uncut Gems, has a despicable lead character in Connie, who does some terrible things in the film. But we meet him coming to the rescue of his mentally challenged brother while a heartless social worker demeans him by making him take an uncomfortable test. Instantly, after that scene, we’re rooting for Connie.

And then I just didn’t get what Tomlin was going for here. We’re told that Malcom has been stolen by the Fortification dozens of times and that the Rebellion keeps having to steal him back. Malcom asks the same question we’re wondering. “Why don’t they just kill me?” Rachel explains that if the Fortification kills him, society will know their Trauma-Erasure system doesn’t work. To prove they have everything under control, they must erase his Rebellion memories and reintegrate him back into society every time.

I’m sorry but if I was a citizen in this society and I found out one of our main guys had been kidnapped by the Rebellion two dozen times??? I’m probably thinking the system doesn’t work. And just from an objective storytelling perspective, once someone gets stolen back and forth five times, doesn’t it get a little silly? Once or twice, I get. But 20? 30 times? It’s clumsy storytelling.

Another problem with big sci-fi ideas is over-development of the mythology in ways that hurt the story more than help it. Everyone wears these over-the-top super suits to keep them from transmitting diseases to each other (supposedly). But wouldn’t this movie have been better without this component?

Cause it’s hard enough to buy into this memory impregnating slash memory restoring tug-o-war as it is. When you throw in, “and oh yeah, everyone wears big cumbersome bubble suits,” it draws attention to the very lie the Fortification is trying to hide. Wouldn’t it be a lot easier to trick someone into thinking everything was normal if everyone WASN’T wearing a big weird suit? It’s even one of the first things Malcom notices after the Fortification procedure. Why is everybody dressed so weird? They might as well have given him a handbook that listed all the other suspicious things he shouldn’t pay attention to.

The thing is, once the script hits the midpoint, it actually starts to get interesting. We go back into the memory of Malcom as all the memories he forgot are implanted in him by the Rebellion. And we’re experiencing them as he is. So we see when him and Rachel first meet and fall in love and what goes wrong afterwards that leads to the Rebellion. I wish we would’ve started with that. It was so much cleaner and more interesting than giving us 60 pages of exposition and setup.

Unfortunately, it was too little, too late. My suspension of disbelief had been broken so many times that I couldn’t get back into the story bubble I needed to be in to enjoy the screenplay. Which is too bad. Cause the end scene with the Counselor where he’s explaining everything was quite good.

There’s a kernel of a story in here. But I don’t think Tomlin’s found it in this draft.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Make sure the bad guy has a good point. One of the easiest ways to add depth to your bad guys is to give their ideology legitimacy. When Rachel finally meets the big bad guy and he explains why they do what they do, he makes strong points. Their system has resulted in zero poverty, zero crime, zero wealth disparagement, zero war. Yeah, they do some bad things. But wouldn’t any society kill to have those numbers? You want to make your hero’s choices DIFFICULT, not easy. You automatically do that whenever your villain has a strong argument.

Today’s quirky script feels like something that would’ve topped the 2010 Black List.

Genre: Comedy

Premise: A Jewish immigrant accidentally gets brined in a giant pickle barrel, perfectly preserving him for 100 years, after which he’s discovered and must learn to live in the year 2020.

About: What’s that thing I keep telling all of you to do? What’s that thing I keep saying is the new spec script? Oh yeah, SHORT STORIES. Today’s movie is yet another adaptation of a short story, this one titled, “Sell Out,” by Simon Rich, which appeared in the New Yorker in 2013. Rich started writing short stories for the New Yorker in 2007. He would go on to be one of the youngest writers ever hired on Saturday Night Live. He would later become a staff writer at Pixar. He wrote this screenplay adaptation himself. An American Pickle can be seen on HBO’s new streaming service, HBO Max.

Writer: Simon Rich

Details: 90 minutes long

The great thing about the streaming boom is that it allows for non-traditional movies that never would’ve been produced to get made, widening the breadth of options the viewer has so they aren’t forced to watch superheroes and Jedi every day of the week.

It’s sort of a more audience-friendly version of the independent film boom of the 90s. That era also gave us a bunch of unique options when we went to the theater. But there’s more of a commercial spirit to today’s offbeat choices. An American Pickle feels like a weird hybrid between a Charlie Kaufman movie and Pineapple Express.

It begins with Herschel Greenbaum, a Jewish man who, with his wife, escaped poverty and war to immigrate to the United States in 1919. When he accidentally falls into a pickle brining barrel at his work, he is preserved for 100 years and wakes up in the year 2020.

The good news is that Herschel has a great-great-grandson, Ben, who allows him to stay at his place in Brooklyn. After getting used to all the creature comforts of the 21st century (Herschel has a particular affinity for seltzer water), Herschel finds out that Ben has spent the last five years trying to perfect his big idea app which tells you whether a company is ethically responsible or not.

Herschel asks why hasn’t he actually, you know, started the company? Ben makes excuses, saying it still needs work and blah blah blah. Herschel is confused. It looks ready to him. Later that day, the two get in a fist fight with two guys on the street due to a misunderstanding by Herschel, which leads to their arrest. Just like that, all Ben’s work has gone down the drain. How can you have an app that rates how ethical you are if you, yourself, have been arrested for assault and battery!

Ben kicks Herschel out, who now sees Ben as his nemesis. He decides to start a business in what he knows best – PICKLES! Herschel finds hundreds of daily discarded cucumbers and jars in the dumpster behind a supermarket and begins making pickles. When a hipster Brooklyn blogger stops to have a taste and learns that these are the world’s most natural pickles (Herschel even uses God’s water – rain!), Herschel becomes a social media sensation.

Ben becomes furious that Herschel has found success when he’s failed and makes it his mission to sabotage Herschel. After getting the New York Health Board to shut Herschel down, Herschel somehow becomes even more popular via his brash antiquated views on society. Women belong in the kitchen, he insists (keep in mind, he’s from 1919 Eastern Europe), and before he knows it, he has millions of conservative Americans thanking him for challenging the restrictions on free speech.

But when Herschel finally gets canceled, he’s forced to crawl back to Ben and ask for help. Ben decides to help him get to Canada and, along the journey, realizes that Herschel is the only family he has. The two apologize to each other and begin their friendship anew.

I have a bad habit whenever I start a movie where I check the running time. There’s an industry secret when it comes to running time. If a film is exactly 90 minutes, there was trouble somewhere along the way.

Outside of some super contained thrillers and pared down horror films, nobody sets out to make a 90 minute movie these days. There’s no need to. Sure, back when you had to pay for film, it made sense. But not when you shoot on unlimited storage drives. So when you see a 90 minute run time, the unofficial shortest running time the feature format allows, it’s an indication that the producers had so little faith in the movie they shot that they cut as much of it out as possible.

Which is exactly how American Pickle felt at first. After Herschel gets to the future, we get a 12 minute two guys talking in an apartment scene, which was odd considering this movie had the kind of budget that allowed it big special effects time-lapses of New York changing over 100 years. It felt like we’d missed something, a whole other subplot that had been axed, maybe.

But American Pickle picks up once Herschel and Ben become enemies. No doubt the ‘rivals’ plotline was manufactured. But you quickly overlook that because Herschel’s pursuit to become a pickle magnate was so funny. The idea of making pickles you found from the garbage and selling them for 12 dollars a piece in Brooklyn rides the line between reality and satire so perfectly, you can’t help but laugh when customers eat Herschel’s schtick up.

What I also liked about American Pickle is that it was ambitious. Simon Rich wanted to make a statement about where we were as a country and he used Herschel in every way possible to put a mirror up to ourselves. When Herschel learns about Twitter and starts making controversial statements and getting canceled for it but then also supported for it, it was a way to look at our current situation without ever getting into the annoying angry argumentative side of things. You could laugh no matter which side you were on. That takes a lot of skill in this environment.

The only reason I’m not rating this movie higher is the clumsily explored religious plot line. There’s this subplot about Herschel wanting Ben to take ownership of his Jewish heritage and Ben resisting. But it’s so scattered and inconsistent that it never works.

I suspect this is where the cuts happened that resulted in the 90 minute runtime. I feel like there were lots of extra religious-focused scenes and they determined those scenes either weren’t working or weren’t funny enough.

The problem is the climax is all about Ben accepting his religion. That meant they were locked into that storyline. So they had to include at least one other major scene about religion, which they did in the first act, and then ditched it until the end. So if that storyline felt off to you, that’s probably why.

It’s an interesting dilemma for screenwriters for sure. These are the kind of subplots that give our scripts meaning. It’s what makes a movie like this more than an Adam Sandler movie. Yet in a comedy, these are always the first scenes to get cut. The producers are looking at that edit every day nervous about the script losing momentum, nervous about 2-3 minutes going by without a laugh. And because they’re watching it over and over and over again, they have even LESS patience than the audience. So bye-bye religious plot.

But, as screenwriters, I believe we need to leave these plots in the script. If they don’t make the final cut, th e’s nothing we can do about that. But these are often the scenes that make the reading experience more potent and, therefore, our scripts more memorable.

On top of everything else, Seth Rogen does a great job as both characters, especially Herschel. I would often forget they were the same person. I’m usually wary of these “one actor two roles” movies because they’re always vanity projects. When was the last time one of these “one actor two roles” things genuinely worked? The Social Network? And that wasn’t even a vanity project. Armie Hammer was just trying to get a job. But yeah, as crazy as it is to say, the chemistry between Rogen and Rogen was really good.

If you have HBO Max, check this out!

[ ] What the hell did I just watch?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the stream

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: This movie doesn’t take off until Herschel has his goal – create a successful pickle business. Before that moment, I was sitting there thinking, “What the heck is this movie about??” So if your movie is wandering, or you’re getting that note from people, just have one of your main characters establish a STRONG GOAL. And he’ll bring the movie with him. That’s the thing about a character goal. It’s not about saying, “Screenwriting books say I need a goal so I must include one!” No no no. The reason you include a goal is because every goal requires ACTION to obtain it. In other words, a goal instantly makes your character ACTIVE (ACTION = ACTIVE). And characters who are active are always more interesting than characters who are not.

As some of you know, I used to play tennis competitively. Before Scriptshadow, I taught tennis for almost a decade. Unfortunately, teaching got me so burned out on the sport that I eventually limited my tennis exposure to raising my fist from the safety of my couch whenever Federer hit a passing shot on TV.

However, I’ve started to play again, and something I found which I didn’t have available to me when I was playing is Youtube. There are now hundreds of tennis pros teaching the sport through the internet. And a handful of them are really good. So good that I’m learning a bunch of new things that nobody ever taught me when I played (i.e. wrist lag, unit turn).

These things have allowed me to hit the ball with more confidence than I had even back when I was playing competitively! What sucks, though, is that I’ll never have the speed and quickness I had when I was 21. That’s the downside of sports. True, the older you get, the more knowledge you gain. But also the more athletic ability you lose. John McEnroe knows ten times as much about strategy as Rafael Nadal. But McEnroe is 60 so it doesn’t matter.

Why I am dragging you down this depressing road? Actually, there’s a silver lining to this anecdote. It made me realize that with screenwriting, THERE IS NO PHYSICAL REQUIREMENT. You can learn new things at 40, at 50, at 60, and KEEP GETTING BETTER. Nothing is stopping you from doing so.

There is a caveat to this, however. You have to be willing to be a STUDENT OF THE CRAFT. There is another version of Tennis Carson who thinks he knows everything. Bizarro Tennis Carson would never look up instructional videos on Youtube. He already knows it all. I see this same hubris in writers all the time. They think they’ve eclipsed some skill level that anoints them “learned everything they need to learn.”

The second you think you’ve learned everything, you’re toast. This is why you see wunderkinds come out of nowhere in their early 20s only to become one-hit wonders. Shane Carruth. Richard Kelly. Success gave them the impression that they didn’t need to learn anything else. After Primer, Carruth thought he was God and, as a result, spent the next two decades miffed that nobody understood the 500 page script he’d written about ice dragons.

I hear from writers 50 years old and older all the time concerned that Hollywood doesn’t want them because of their age. That’s not the way to look at it. You have more knowledge about this craft (not to mention, life experience) than 95% of the people out there. That’s a huge advantage.

The real reason most older writers struggle is because the older you get, the more you gravitate towards slow low-concept ideas. I see this a lot. I’ll read a slow moving medium-level concept and when I check the e-mail, the writer either says or hints that he’s older. Their understanding of the craft, their plot execution, and their character writing are always better than younger writers. But you can’t escape an unexciting idea.

Meanwhile, young writers have the opposite problem. They usually come in, guns blazing, throwing out the coolest idea ever. But when it comes to execution, there’s an inherent sloppiness. The writers have somewhat of a grasp on the fundamentals. But you can tell they haven’t been on the ice long enough to land a double-axel.

Just this week, I ran into a great premise for the contest. It was Harry Potter set in an inner city school. But the script only managed a “LOW MAYBE” because the execution was wobbly. And yes, the writer is young.

I’m telling you this so that you always keep trying to learn. There was a time before I started Scriptshadow where I thought I knew everything about screenwriting. I really did. Do you know how many new things I’ve learned about the craft since then? Easily 300. Probably closer to 500. A lot of that from reading screenplays.

One in particular is “dramatic irony.” That’s when you put your hero in a situation where we know they’re in trouble but they don’t. It’s the famous rooftop scene between John McClane and Hans in Die Hard. We know that’s a terrorist. But McClane thinks he’s a hostage. I can’t imagine writing a script without knowing that today. It’s one of the best ways to create suspense and tension in a scene.

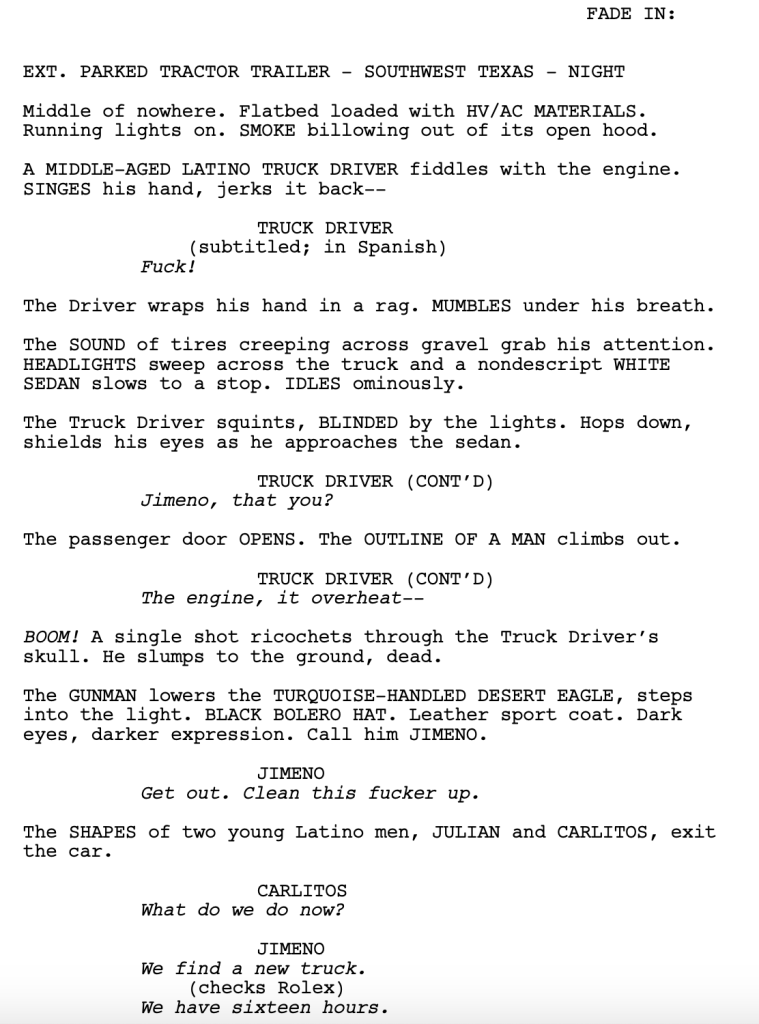

I want to finish off today by featuring the first page of a script that made it into my “HIGH MAYBE” pile for The Last Great Screenplay Contest. For those who haven’t been following the contest, I’m in the process of reading the first ten pages of each entry and then I put the script in the “NO,” “LOW MAYBE,” “HIGH MAYBE,” or “YES” pile. The large majority of the scripts are ending up in the NO and LOW MAYBE piles. So if you get into the HIGH MAYBE, you’re doing something right.

This script – to tie it into today’s theme – helped me re-learn something I always forget the importance of. I’ll read two scripts back to back and they’ll be covering the same subject matter. Someone is murdered. Marines out in the battlefield. A meet-cute scene. But one script will be noticeably better. And what this writer demonstrates is the reason. Let’s take a look…

What writer Chris Dennis does so well here is he uses words to create sounds and images that put you inside the story.

“SMOKE billowing out of its open hood.”

“SINGES his hand, jerks it back—“

“The SOUND of tires creeping across gravel…”

“HEADLIGHTS sweep…”

“IDLES ominously.”

“squints, BLINDED by the lights.”

“shields his eyes”

“He slumps to the ground”

“BLACK BOLERO HAT. Leather sport coat. Dark eyes, darker expression”

Even if you only read these snippets I highlighted, you’d feel the intensity of the scene. That’s how effective this type of writing is. You’re seeing these images. You’re hearing these sounds.

What’s cool about this is that he never overuses the description. That’s the reason most writers shy away from this sort of thing. They think it bulks up the description. But there’s only a single paragraph on this page that reaches three lines. You can do this and still keep the writing lean.

So those of you self-professed students of the craft – which should be all of you – you now have a new skill to try out. Get to writing!