Search Results for: the wall

Genre: High School Comedy

Premise: A teenage friendship is tested when one of the friends informs the other that he’s gay.

About: Gay Dude was on the 2008 Black List. It subsequently disappeared into the Hollywood ether before popping up as one of the projects on Lionsgate’s new “microbudget initiative,” a new production initiative stemming from the success of movies like Paranormal Activity. The group of movies will be shot for around 2 million dollars. The writer of Gay Dude, Alan Yang, has been quite successful since Gay Dude got him noticed. He’s worked on Parks & Recreation, sold a bromance pitch to Summit called “We Love You,” sold a spec “White Dad,” to Sony. He also has a script called “Jackpot” set up at Fox about a group of high school friends who win the lottery.

Writer: Alan Yang

Details: 108 pages – undated (This is an early draft of the script. The situations, characters, and plot may change significantly by the time the film is released. This is not a definitive statement about the project, but rather an analysis of this unique draft as it pertains to the craft of screenwriting).

Here’s the shitty reality about readers. They don’t always give you a fair shot. It just happens that sometimes your script hits a reader at the wrong time. They’ve read five terrible scripts in a row and are assuming yours will be the sixth. It’s been a bad day. It’s been a bad week. They just got dumped. Their boss is an asshole who deluges them with the worst of the worst screenplays to cover. Sometimes a reader is just ready to hate your script. And it’s unfair and it sucks but life is unfair and sucks so…that’s reality baby.

Gay Dude is a perfect example of that. I remember reading it during a period where I was reading seven scripts a day (due to a contest) and I’d just read four really terrible comedies whose collective awfulness had actually managed to destroy humor for 47 minutes in the world. So within fifteen pages of the sophomoric humor of Gay Dude, I had already hit “skim-mode.” (this is the dreaded mode readers get into when they’ve given up on your script).

This is the real reason I preach all this advice about keeping your writing concise, being clear with your descriptions, not writing scenes that don’t push the story forward, not adding characters you don’t need. So that you don’t lose your reader in those crucial first 10 pages. Because many readers are looking to disqualify you as soon as possible so they can skip through your screenplay and be done with work an hour early. Again, it’s unfair, but a 9 to 1 bad script to good script ratio will do that to a person.

Long story short, I felt like Gay Dude needed another shot. I hadn’t read ANY scripts on the day that I picked it up this time, so I could be sure that I was giving it the best chance to succeed. I’m not going to lie and say it blew me away or anything. But it was a lot deeper than I originally gave it credit for.

Eager Michael and chubby Matty have been friends for as long as they can remember. Now in high school, they’re only a couple of months away from prom. And they’ve decided to make an American Pie like pact to get laid before the big day is over. That’s why they…um…break up with their girlfriends?

Yeah, these two aren’t the brightest string lights at the prom dance but Michael seems to think they can do better. Except a little problem pops up before better can make his presence known. Matty informs Michael that he’s, like, gay dude.

Michael thinks he’s joking but he’s not joking. Matty likes the scrotum. Michael’s a little weirded out by this. This is, remember, a person he’s been best friends with since he was two. So he retreats into “what the hell is going on” mode before finally strapping on his support cap and refocusing on their goal – to get laid before prom. It’s just that now half of their search will include…men.

The problem is Michael becomes TOO supportive, forcing Matty to visit places like the only gay bar in town, which consists of a bunch of old dirty gay guys. Since Michael figures “gay is gay,” he assumes it’s what Matty wants. But Michael’s off-target assessment begins to grate on Matty, who eventually finds a guy his own way, and that guy becomes, well, sort of a replacement Michael.

The lack of communication feeds the downward spiral of their friendship until there’s no friendship left, leaving both friends to wonder how those two words could have changed so much.

Gay Dude made a couple of really good choices that elevated it above normal teenage script fare. The dialogue was good and Yang actually explored the friendship on a real level. Let’s start with the dialogue. The back and forth between these two was organic, witty, and popped off the page. We’d get exchanges like this one, where Michael talks about his prudish girlfriend, “It was like a sexual brick wall with Ava. The last couple of dates we were moving so slowly that we were actually going backwards. Three dates from now we would’ve been bowing to each other and speaking in formal, turn-of-the century English.” “Good morrow to you, sir.” “Good day to you, madam. Shall we wait another fifteen years to commence the fucking?”

Or this exchange, where Michael tries to find out when Matty knew he was gay. “When did you first realize this? Like, is this a recent development?” “Fuck no. Remember that guy, like when we were like seven, he used to come around the school and we would slip him half our sandwiches through the chain link fence?” “That guy was a homeless guy.” “Yeah, well, I sort of had a crush on him.” There’s a lot of fun back and forth like this throughout the script.

But what really sets Gay Dude apart is that it actually explores its characters (and their relationship) on a real level. And this is where so many amateur comedy screenplays fail. They think it’s about packing as many jokes as they can inside 100 pages. Laughs will only get you so far. Sooner or later, you need to connect with the audience. And Gay Dude isn’t afraid to tackle those confusing and frustrating feelings that come with finding out your best friend is gay at a time in your life when you’re not emotionally capable of dealing with it. Late in the script, it’s clear that if the two just sat down and talked, they’d get past this. But they don’t know how to do that. So instead they lash out each other (Michael tells Matty’s homophobic father that he’s gay) and everything gets a lot worse before it gets better.

The problem Gay Dude runs into is that it does feel a little one-note. There isn’t enough variety in here to last an entire film. I felt like the characters were having the same conversations (“It’s not easy to find out you’re gay!”) over and over again. In addition, there wasn’t enough variety in the set pieces. For example, we go to a gay bar. And then after that doesn’t work, we go to a gay rave. It’s important, especially with a concept like this which has the potential to be “one-note,” that you really try to differentiate your set pieces.

There’s also a story thread where Michael starts suspecting Matty is faking being gay that doesn’t go anywhere and actually ends up confusing the story as opposed to helping it (if he isn’t gay, why does this story matter?). It’s not a huge deal, but again, I think this stemmed from the fact that the story was one-note, and SOME sort of complexity needed to be added. I just didn’t think it was the right complexity.

Anyway, I do think Gay Dude is worth the read. It digs deeper than most comedies, which in turn makes us care about the characters, which should be priority number 1 in any genre you write. By no means perfect but a breezy 90 minutes nonetheless.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Story over shenanigans people. If you’re trying to decide between a scene in your comedy where you’re adding yet ANOTHER silly situation, or getting into the meat of your characters issues, pick the issues. Strive for a balance overall, but don’t be afraid to get into your characters real problems. Remember, we’ll laugh a lot more if we actually care about these people. Gay Dude proves that.

Genre: Drama /Horror

Premise: After his wife goes missing, a man heads to the darkest reaches of Transylvania to find her.

About: Every Friday, I review a script from the readers of the site. If you’re interested in submitting your script for an Amateur Review, send it in PDF form, along with your title, genre, logline, and why I should read your script to Carsonreeves3@gmail.com. Keep in mind your script will be posted.

Writer: Lee Matthias

Details: 107 pages (This is an early draft of the script. The situations, characters, and plot may change significantly by the time the film is released. This is not a definitive statement about the project, but rather an analysis of this unique draft as it pertains to the craft of screenwriting).

What if your wife got kidnapped? And what if you found out the man who took her was the most notorious blood-sucking vampire in history? How far would you go to try and get her back? Those are the questions posed in the mysteriously titled, “The Sleep Of Reason,” the first amateur script I’ve read in forever that I believe is worthy of your time. And a big reason for that is, I’ve never seen a “Dracula” story taken this seriously before. This is one part Dracula, seven parts character study. That’s what makes The Sleep Of Reason so unique. It doesn’t rest on the laurels of its famous character. It’s more about the man who must overcome him.

Sleep of Reason didn’t start off well for me. There’s a big difference between complex openings and confusing openings. Complex openings create interesting questions the reader wants answers to. Confusing openings leave readers frustrated and trying to keep up. These openings are usually the result of a writer trying to cram too much into their setup. Because they’re so familiar with the elements in their story, they wrongly assume you’re familiar with them too.

We start off Reason on a boat (for seemingly no reason), then jump to an insane asylum, then jump to a man in that asylum interviewing a crazy person, then jump to that interviewer’s predecessor at the asylum from a few years back, who then helps us jump back 35 years prior to understand why this man went crazy. It was just so many elements coming at us so fast and in such a disjointed fashion, I had to reread it a couple of times to understand what was going on. You never never never want your reader to have to go BACKWARDS to check something in a script. It takes them out of the story (literally) and screws up the rhythm of the read.

Luckily, once we move out of the present day storyline, things pick up considerably. Renfield (our crazy character and hero) is the son of a wealthy entrepreneur on a trip to America to explore some business opportunities, when he meets and falls in love with Elsbeth, a poor but beautiful young woman.

Unfortunately, because Elsbeth is a woman of simple means, Renfield’s father doesn’t approve of their union, cutting the two off from the family. This forces Renfield to pursue a career on his own, and their first option is a contact he knows in the furthest reaches of Eastern Europe. It is there, in a small town, that Renfield leaves his hotel for just a moment, before coming back and finding his wife gone. Her disappearance is particularly upsetting because…it’s impossible. He was outside the hotel for just a few minutes and never saw her leave. It’s as if she just…vaporized.

Naturally, Renfield becomes consumed with finding his wife, and after experiencing many roads that lead nowhere, he finally gets a clue about a mysterious resident who lives up in the mountains in a castle. Against the advice of the townspeople, he heads up to that castle, and finds it occupied by a curious group of people who welcome him with open arms.

After a couple of nights of wandering through the cavernous castle walls, Renfield befriends the irresistibly sexy Elizabeth, who informs Renfield that his wife is here in the castle. There’s a problem though. Vlad, the owner of the mansion, has become enamored with her. Soonafter we realize that Elizabeth is just as heartbroken about the chain of events as Renfield, as it used to be her who was the apple of Vlad’s eye.

The two must work together, then, to create a mutually desirable outcome. But it won’t be easy. When Vlad finds out what they’re up to, he plots to make things very difficult for Renfield.

After getting through that tough opening, I realized something quickly. Lee was a really good writer. I can’t remember the last time I came upon an amateur writer who had such command of language and story. And it gave me an immense amount of confidence in the script. I immediately felt like I was in good hands.

Indeed I was rewarded when Renfield got to the castle as that’s when everything really began to pick up. The conflict Lee creates and the clashing motivations of all the characters make for some really great tension. You have Renfield, who wants to get his wife back. You have Elizabeth, who wants Vlad back. You have Vlad, who wants to keep Elsbeth. And you have Elsbeth, who wants Renfield, but is too deep under Vlad’s spell to do anything about it. Complicating things even more is the vampire angle. Even if Renfield is able to get his wife back, how does he get around the fact that she’s now a vampire?

I also loved the tone here, and Lee achieves this quite cleverly. In order to protect himself from all of the vampires in the castle, Renfield keeps with him a special case of garlic-laced brandy. He must keep drinking the brandy to keep the garlic in his blood. The side effect of this, however, is that Renfield is always slightly drunk, which gives his actions and his experiences a dream-like quality, and puts into question everything he’s doing. Is he really here? Is this really going on? Are these people really who he believes them to be? Does he want his wife so badly that he’s merely creating this story in his head? It felt a lot like Black Swan in that sense, where we’re constantly questioning reality.

That’s not to say The Sleep Of Reason didn’t have some hiccups. I wasn’t entirely clear on why Vlad didn’t just kill Renfield and get it over with. Possibly establishing that Elsbeth would’ve never forgiven Vlad if he’d done such a thing would’ve helped.

Also, the pace is a little slow. I’m afraid some readers are going to be like, “Let’s get on with it already!” And I guess I’d understand that argument.

But the reason I think the slow pace works here where it didn’t work in, say, Tripoli, is because Reason has something Tripoli did not: Personal stakes for its protagonist. At stake here is Renfield’s wife – the woman he loves more than anything. So even though it takes awhile to get to things, we’re willing to wait because the goal is so strong.

The Sleep of Reason is a thousand times better than most Amateur scripts I read. The attention to detail alone proves how much Lee cares about this story and how much he respects the craft. It’s slow-going in places and the writing is a little thick at times, but there’s enough conflict and a strong enough character goal driving the story, that it all works out. Granted I’m not a Dracula fan, but this is the best Dracula story I’ve read easily.

Updated Script Link (with changes): The Sleep Of Reason

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: One of the mistakes I see intermediate to even advanced writers make is trying to cram too many elements into the opening of their scripts (voice overs and flashbacks and jumping back and forth between unrelated scenes). I think these writers are simply trying to create complex multi-faceted openings. But they forget that the reader is entering their world for the first time and needs to be oriented before they can handle all the craziness. You can’t throw me into the middle of the world Crickett Championships if I don’t know the rules to the sport. So just take a step back when you’re writing that opening and say, “Am I trying to do too much here? Am I asking too much of the reader?” Because if you lose your reader within those first ten pages, your screenplay is screwed.

Genre: Historical Epic

Premise: In 1804, before America has any cachet in the world, a rogue U.S. diplomat arrives in the savage city of Tripoli to demand the release of American prisoners.

About: Tripoli was famously about to begin production in 2003 (2004?) when at the last second the studio pulled out. Ridley Scott, the director of the project, immediately moved on to another Monahan scripted endeavor, “Kingdom Of Heaven.” Tripoli has made waves in screenwriting circles since, with many proclaiming its awesomeness. As I’ve found this to be standard practice when it comes to deserted high profile projects, I decided to read the script and decide for myself. Monahan is pretty much the go-to guy when it comes to historical-based screenplays and is one of the better writers in Hollywood overall (I really dug his underrated screenplay for Edge of Darkness

). He actually sold this screenplay on spec.

Writer: William Monahan

Details: 129 pages – 4/11/02 draft (This is an early draft of the script. The situations, characters, and plot may change significantly by the time the film is released. This is not a definitive statement about the project, but rather an analysis of this unique draft as it pertains to the craft of screenwriting).

Historical-related plots are so hard to pull off. They’re always walking that line between maintaining the historical accuracy of the times and keeping things entertaining enough for a modern audience. The problem is that the speed of life back then was so damn slow, and if you violate that pace, if you try to speed it up Michael Bay style, it feels false, necessitating that you move your story along at “Sunday afternoon” speeds. This requires the writer to dig deep into his bag of tricks to keep the story moving – conflict, mystery, suspense, tension, plotting – all of them must be used to “trick” the audience into thinking things are moving faster than they actually are. The problem is, there aren’t many writers who can do this. But since Monahan is about as skilled as they come, maybe Tripoli would be different.

Or…maybe not.

I didn’t like Tripoli. In fact, I had a harder time getting through this than I did a day at Sunday school. I don’t know if this movie was built for me because it is looooooong and drawwwwwwn out and not much happens and I don’t know if the subject matter is big enough for an entire movie. It’s basically about a guy walking around for a couple of hours. Let me lay out the plot for you.

The story starts off in the Barbary Coast of Africa in 1804. America isn’t a major player yet. To the point where places like Tripoli scoff when Americans show up in their city and demand the release of American prisoners. This is exactly what happens as our hero, Eaton, an easily frightened American diplomat on his way to another country entirely, but who gets roped into Tripoli after local pirates seize his ship, sees other Americans there and asks for their release.

This was the first sign of trouble for me, that our hero wasn’t even specifically headed to Tripoli in the first place. He was going somewhere else and only upon noticing a few of his other countryman being held did he decide to make a stand. When the situation was so meaningless that our hero wasn’t even going there to address it in the first place, it just felt like a second rate problem. And indeed, the Americans aren’t in any imminent danger. They’re just sequestered to their ship in the port. So right away, the stakes feel low.

To the script’s credit, there is one great sequence in this opening act, and that’s when Eaton demands to speak with the city’s ruler, a barbaric man who skins people alive, pokes their eyes out, and forces them to live in cages in his throne quarters. And we thought Charlie Sheen had issues. Just the anticipation of this meeting between Eaton and the ruler was great, and when they do finally have their showdown, and Eaton stands up to him, it was easily the best moment in the script. I still had high hopes for Tripoli at this point.

Unfortunately, Monahan takes the story in another direction entirely. After the ruler denies Eaton the release of his countrymen, Eaton finds out that the king has a brother who’s been exiled to Egypt, and that this brother is a way cooler cat who doesn’t skin people alive and put them in cages. So he gets this idea that he’ll go to Egypt and convince the brother to come back and rule Tripoli.

And thus begins an endless trip where Eaton finds the brother and the two walk back to Tripoli, debating how they’re going to take over the city with so few men. As you know, for any “road trip” scenario to work, the characters have to be interesting. And both Eaton and the brother are – I hate to say it – but really boring. They sound like two college professors debating 200 year old world affairs for two hours. I mean it’s really hard to get through.

I suppose the final battle to take the city back could be epic with Ridley Scott directing, but because I didn’t care about any of the characters involved, in particular the American soldiers who I barely knew, the battle didn’t matter. To make things worse, there’s a huge anti-climactic moment that interrupts the battle at the end that basically makes everything that came before it (aka the entire movie) meaningless.

Tripoli’s faults come down to that most basic pillar of storytelling – stakes. I just didn’t feel the stakes. I didn’t really know or care about the Americans being saved. I didn’t understand why replacing the leader of Tripoli was so important. It seemed like our main character was set on it only because of principle, because the ruler was bad and his brother was good. I get principle but I don’t know if I believe that someone takes a months-long trip to Egypt to find a replacement king then goes back and tries to take over the city simply on principle. In Braveheart, if William Wallace loses any of those battles, his country loses their fucking freedom!! Now THOSE are stakes. Replacing the ruler of a mean but small group of savages who annoyingly interrupt European trade routes with their piracy? I’m not sure why I’m supposed to care about that.

Also, I didn’t like the recruiting of the replacement brother. Mainly because the CITY IS WHERE ALL THE FUN IS! Tripoli, with this barbaric insane leader who kills people for sport….THAT’S WHERE I WANT MY MOVIE TO BE. That’s where all the conflict is. When we’re in this city, we feel like Eaton could be skinned alive at any moment. When he’s off wandering around Egypt, we feel no danger for him whatsoever. Why not have Eaton stay in the city and plan his takeover there? I suppose the answer to this has something to do with that’s not how it happened in real life. So then maybe you focus the story on one of the other characters, possibly one of the Americans stuck in the city?

To be honest, this is why I get worried whenever I open a period piece. Many of them seem to be geared towards historical nerds who love the details yet aren’t that interested in telling a rip-roaring story, which I guess brings us back to Monday’s script review, Repent Harlequin. The details are definitely necessary to making a script great. But a script’s laurels can’t rest solely on historical details. It has to be based on some kind of unique entertaining hook, and I’m still struggling to figure out what the hook of Tripoli was.

So if William Monahan, one of the best writers in Hollywood, is struggling to make an historical epic work, then let that be a word to the wise for all you amateur writers out there thinking you’re going to break into the spec market with an historical/period piece yourself. It’s really damn hard!

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: If you refuse to listen to me and still want to write your period piece, seriously consider starting your screenplay with an opening crawl that highlights the relevant details of the time. One of the reasons I had such a tough time getting into Tripoli was that I had no knowledge of this time period or this city. If there are some important details about why Tripoli is the way it is or what stage America is at right now, the reader needs to know (i.e. “In 1807, pirates out of Tripoli were wreaking havoc on the surrounding countries, severely crippling the most important trade routes in Western Europe, which in turn crippled America’s commerce…”). Set up for us why this story is relevant.

Genre: Drama

Premise: The real life story of a vacationing family’s struggle to find each other after the infamous 2004 Indian Ocean Tsunami.

About: Thought this script was somewhat relevant considering Friday’s horrible events in Japan. I’m also reviewing it as a reminder to help out if you can. Please donate to a relief fund if possible. — The Impossible made the lower half of 2010’s Black List. Sergio Sanchez, the writer, is also the writer of one of the best horror films I’ve seen in the last five years, The Orphanage. The film is in post-production now and stars Ewan McGregor and Naomi Watts.

Writer: Sergio G. Sanchez

Details: 102 pages (This is an early draft of the script. The situations, characters, and plot may change significantly by the time the film is released. This is not a definitive statement about the project, but rather an analysis of this unique draft as it pertains to the craft of screenwriting).

In the eternal battle to determine just how important structure is to screenwriting, I’m tackling a couple of screenplays this week where it can be argued that neither adheres to the three-act structure, starting with today’s script, The Impossible, and then a breakdown of the well-known classic, The Breakfast Club, on Thursday. Here’s how I see it. If you’re not going to have three structured acts propping up your story, you need a driving force that’s so strong, so compelling, we won’t notice or care. The Impossible is a good example of this. This is a movie about survival against insurmountable odds and the search for one’s family. Our need to see these characters succeed in these endeavors diminishes the importance of that success coming via a traditionally told narrative. I will never outright recommend this approach, but if it’s going to be done, this is one way to do it.

Maria and her husband Henry, two Brits by way of Japan, are taking their three children, Simon (5), Thomas (7) and Lucas (11) on vacation to Thailand for Christmas. Like a lot of family vacations with young kids, the work load of organizing everything makes the vacation more work than fun. Maria and Henry are simply trying to manage each problem as it comes up until they can get onto one of those pristine Phuket beaches and relax for an hour or two.

How ironic, then, what will happen on that beach once they get there. Like a lot of people on that fateful day, Maria’s family was simply enjoying a relaxing day on the water when they looked up and saw a terrifying black wall coming towards them. Scattered about with no time to react, all they could do was brace themselves, and the next thing they knew they were pushed out into the streets grasping for any lifeline they could find.

Maria and Lucas get separated from Henry, Thomas, and Simon, and they’re who we start with. Battling currents so strong, cars are whipping by, Maria and Lucas are able to survive the initial wave, but barely. Maria is a wreck, with cuts so deep, pieces of flesh are hanging off her body. Lucas is horrified to see his mother in this condition, but must focus on the task at hand. Find a hospital.

When they finally do get to a hospital, it’s chaos. People with wounds or ailments that would usually get immediate priority are staggering around aimlessly while nurses and doctors ignore them. It’s chaos of the highest magnitude. Which is trouble, as Maria is fading fast. A doctor herself, she knows she doesn’t have long to live. Yet she and her oldest son must sit around and hope amongst hope that sooner or later, someone will give her the medical attention she needs.

Eventually Lucas goes off to find help on his own, but is horrified (spoiler) when he comes back to find out his mother has died. Now Lucas, an 11 year old boy, must hunt across this flooded wasteland, to try and find his father. If, that is, he’s still alive.

The Impossible is an emotionally draining read. And a strange one when compared against traditional storytelling practices. In the first 20 pages alone, nothing happens. And I mean nothing. The family lands in Thailand. They give each other Christmas gifts. But we don’t learn ANYTHING about these people. No problems, no issues, no eccentricities, no personality traits. It would be like getting a real-life snapshot of a family for a few hours. Chances are their interactions would be directionless and boring.

However, this does help The Impossible maintain an essence of realism. The writer’s goal here is not to give you character flaws or a complex plot. It’s simply: Normal family going about their business. Something extraordinary happens. And just like that, this normal family, which could have been yours or mine, is stuck in a life or death situation impossible to prepare for. This is why the lack of three acts doesn’t matter. Because the forces driving the story are so strong. Survive and find the people you love.That’s all we care about.

But don’t be fooled. It’s not like all storytelling has been abandoned here. If you pay close attention, there are character goals at every corner, driving us forward one sequence at a time. The first goal is: Survive. Lucas and Maria are stuck on a tree. And they must survive that initial wave. After that, the goal becomes get to higher ground. After that, the goal becomes getting up on another tree before the next wave comes. After that, the goal becomes finding a hospital. After that, the goal becomes finding a nurse who will help them. After that, Lucas must help others. So while the story’s strength is its sort of “realistic directionless narrative,” one of the reasons we don’t get bored is because the characters are always going after something.

Not surprisingly, the only artificial element here is the attempt to give Lucas a fatal flaw. There’s this whole thing where Lucas feels like he’s not brave, and each situation they find themselves in tests that flaw. But whenever these moments appear, it was like a Hollywood crew showed up to remind the actor playing Lucas of his character arc, and to convey the flaw as aggressively as possible. If I were Sanchez, I would just drop this. The rest of the movie is raw and real. You might as well keep all the character motivations raw and real as well.

Just on a visceral level, The Impossible sticks with you. It’s a reminder that unless you’ve lived something or done a ton of research on something, you won’t be able to convey a truly realistic vision of what you’re writing about. I mean here we get these horrifying images of Maria with half her breast cut off. We have our characters watch hopelessly as cars float past with babies still strapped in the back seat. People stand in shocked daze as big spiders crawl over their faces, unseen, uncared about. It’s very specific stuff that I don’t think a fictionalized account of this tragedy could’ve captured.

The Impossible is a different kind of script. It has big strengths and big weaknesses and is messy and frightening and challenging all at the same time. The dialogue is all on the nose and relatively boring. Yet I didn’t care for some reason. I just wanted to see these characters survive. Ultimately, the determining factor for a screenplay is: “Do I want to keep reading?” If I had the chance to stop, would I? For a large majority of the screenplays I read, the answer to that question would be “Yes, I want to stop.” But for The Impossible, despite all of its faults, I wanted to get to the end. So if you want to read something that breaks the rules and study why it still holds your interest, this is a good screenplay to check out.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: I’m torn about the opening 20 pages of The Impossible. During this time, NOTHING HAPPENS. No plot to speak of. The characters don’t have any issues to be resolved. It’s a very mundane boring snapshot of a family. However, this realism is required to sell the moment when the tsunami arrives, as Sanchez is trying to convey that this could be any family, including your own. BUT, Sanchez wrote a popular highly acclaimed movie before this with The Orphanage, which means whoever’s reading his script is going to trust him, even if things take awhile to get going. You, however, don’t have the same success on your resume. So if you took this same approach, the person reading your script might give up before they ever got to the tsunami. So I’d still say that making SOMETHING interesting happen in those first 20 pages (and preferably 10 pages) is the way to go if you’re an unknown writer writing a spec. For example, you might start with the family on the beach, going about their business, then we hear a couple of screams, and cut to a wide shot showing a HUGE WAVE racing towards us. Then CUT to the plane ride 8 hours earlier and proceed the same way the rest of the story was told. It’s a little gimmicky (and yes, I’ve railed against this approach before), but you kind of have to pick your poison. At the very least, the latter option catches the reader’s attention.

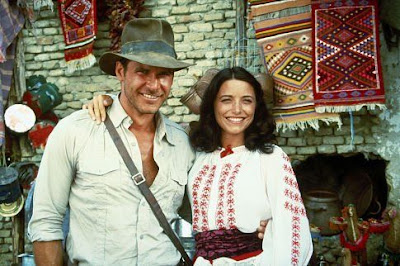

A couple of weeks back I posted my “10 Great Things About Die Hard” article and you guys responded. To quote Sally Fields: “You loved it! You really loved it!” Since I had so much fun breaking the movie down, you can expect this to be a semi-regular feature, and today I’m following it up with a film I’ve always wanted to dissect: Raiders Of The Lost Ark.

When it comes to summer action movies, there aren’t too many films that hold a candle to the perfectly crafted Raiders. Many have tried, and while some have cleaned up at the box office (Mummy, Tomb Raider

) they haven’t remained memorable past the summer they were released.

So what makes Indiana Jones such a classic? What makes this character one of the top ten movie characters of all time? Here are ten screenwriting choices that made Raiders Of The Lost Ark so amazing.

THE POWER OF THE ACTIVE PROTAGONIST

At some point in the evolution of screenwriting, a buzz word was born. The “active” protagonist. This refers to the hero who makes his own way, who drives the story forward instead of letting the story drive him. I don’t know when this buzz word became popular exactly, but I’m willing to bet it was soonafter Raiders debuted. One of the things that makes Indiana Jones such a great character is how ACTIVE he is. In the very first scene, it’s him who’s going after that gold idol. It’s him driving the pursuit of the Ark Of The Covenant. It’s him who decides to seek out Marion. It’s him who digs in the alternate location in Cairo. Indiana Jones’ CHOICES are what push this story forward. There’s very little “reactive” decision-making going on. And the man is never once passive. The “active” protagonist is the key ingredient for a great hero and a great action movie.

THE ROADMAP TO A LIKABLE HERO

Indiana Jones is almost the perfect character. Believe it or not, however, it isn’t Harrison Ford’s smile that makes Indy work. The screenplay does an excellent job of making us fall in love with him, and does so in three ways. 1) Indiana Jones is extremely active (as mentioned above). We instinctively like people who take action in life. They’re leaders. And we like to follow leaders. 2) He’s great at what he does. When we see Indiana cautiously avoid the light in the cave, casually wipe away spiders, or use his whip to swing across pits, we love him, because we’re drawn to people who are good at what they do. And 3) He’s screwed over. This is really the key one, because it creates sympathy for the main character. We watch as our hero risks life and limb to get the gold idol, only to watch as the bad guy heartlessly takes it away. If you want to create sympathy for a character, have them risk their life to get something only to have someone take it from them afterwards. We will love that character. We will want to see him succeed. I guarantee it.

ACTION SEQUENCES

When you think back to Indiana Jones, what you remember most are the great action sequences. Nearly every one of them is top notch. And there’s a reason for that. CLARITY . Each action sequence starts with a clear objective. Indiana tries to get the gold idol in the cave. Indiana must save Marion in the bar. Indiana must find the kidnapped Marion in the streets of Cairo. Indiana must destroy the plane that’s delivering the Ark. It’s so rare that we see action sequences these days with a clear objective, which is why so many of them suck. Look at Iron Man 2 for example. What the hell was that car race scene about? We have no idea, which is why despite some cool lightning whip special effects from Mickey Rourke, the scene sucked. Always create a clear objective in your action scenes.

REMIND YOUR AUDIENCE HOW DIFFICULT THE GOAL IS

High stakes are primarily created by crafting a hero who desperately wants to achieve his goal. I don’t know anyone who wants anything as much as Indiana Jones wants that Ark. But in order to build those stakes even higher, you want to remind the audience just how important and difficult it will be for your hero to achieve that goal. For example, there’s a nice little quiet scene in Raiders right before Indiana goes on his journey where his boss reminds him what finding the Ark means. “Nobody’s found the Ark in 3000 years. It’s like nothing you’ve gone after before.” It’s a small moment, but it’s a great reminder to the audience. “Whoa, this is a really big freaking deal.”

IGNORE THE RULES IF IT SUITS YOUR STORY

Part of becoming a great screenwriter is learning when rules don’t apply to the specific story you’re telling. Each story is unique and therefore forces you to make unique choices. One of the commonly held beliefs with any hero journey is that there must be a “refusal of the call.” When Luke is given the chance to help Obi-Wan, he backs down, “I can’t do that,” he says. “I still have to work on the farm.” Indiana Jones, however, never refuses the call. And Raiders is a better movie for it. Because the thing we like so much about Indiana Jones is that he’s gung-ho, that he’s not afraid of anything. So if the writers had manufactured a “refusal of the call” moment, with Indy saying, “But I have to stay here and teach. I have a dedication to the university,” it would’ve felt stale and forced. So whenever you’re trying to incorporate a rule into your story that isn’t working, consider the possibility that you may not need it.

GIVE A GREAT INTRO TO YOUR FEMALE LEAD

I can’t tell you how many male writers make this mistake (and how many female writers make this mistake in reverse). You need to put just as much thought into your female lead’s introductory scene as you do your male’s. Raiders is a perfect example of this. Indiana Jones has one of, if not the, greatest introductory scene in a movie ever. If you don’t give that same dedication and passion to Marion’s introduction, she’s going to disappear. That’s why, even though her entrance doesn’t compare to Indiana’s, it’s still pretty damn good. We have the great drinking competition scene followed by the battle with German/Nepalese thugs. The girl is badass, swallowing rum from a bullet hole leak in the middle of a life or death battle! Always always always give just as much thought to your female introduction as your male’s.

ADD IMMEDIACY AT EVERY TURN

The pace of Indiana Jones still holds up today, 25 years later. Not an easy task when you’re battling with the likes of Michael Bay and Steven Sommers, directors who have ruined audience’s attention spans with their ADD like cutting. Raiders achieves this pace not through dizzying editing tricks, but through good old fashioned story mechanics, specifically its desire to add immediacy to the story whenever the opportunity arises. Take when Indy arrives in Cairo for example. The first thing he’s told when he gets there is that the Germans are close to finding the Well of Souls! What?? This was supposed to be a simple one-man expedition! Now he’s in direct competition with a team of hundreds of men??? Because of this added immediacy, the stakes are raised and Indiana’s pursuit of his goal is more entertaining. So always look to add immediacy to your action movie where you can!

IF YOU HAVE A BORING CONVERSATION, INJECT SOME SUSPENSE INTO IT

You are always going to have two person dialogue scenes in your movie. These scenes can get very boring very quickly, especially in an action film. There’s a scene after Indy and Marion get to Cairo where they walk around the city. Technically, we don’t need this scene but it does help establish the relationship between the two, which is important for later on. Now a lesser writer may have sat these two in a room and had them divulge their pasts to each other in a boring explosion of exposition. Instead, Kasdan has them walking around, and *cutting to various bad guys getting in position to attack them.* This adds an element of suspense to the conversation, since we know that sooner or later, something bad is going to happen to our couple. MUCH more interesting than a straight forward dialogue scene between your two leads.

MOVING ON FROM DEATH IN AN ACTION MOVIE

Many times you’ll run into an issue where a major character in your movie dies. Yet you somehow must make us believe that your hero is willing to continue his journey. The perceived death of Marion creates this problem in Raiders. The formula to solve the problem? A quick 1-2 page scene of mourning, followed by the hero being placed in a dangerous situation. The mourning shows they properly care about the death, then the danger tricks the audience into forgetting about said death, allowing you to jump back into the story. So in Raiders, after Marion “dies,” Indiana sits back in his room, depressed, then gets a call from Belloq. The dangerous Belloq questions what Indie knows, followed by the entire bar prepping to shoot him. After that scene you’ll notice you’ve sort of forgotten about Marion, as crazy as it sounds. This exact same formula is used in Star Wars. Obi-Wan dies, we get the quick mourning scene on the Falcon, and then BOOM, tie fighters attack them, seguing us back into the thick of the story.

INDIANA’S ONE FAILURE – CHARACTER DEVELOPMENT

Raiders is about as perfect a movie as they come. However, it does drop the ball on one front. Indiana Jones is not a deep character. Now because this is an action movie, it doesn’t really matter. However, I’d argue that the script did hint at a character flaw in Indiana, but ultimately chickened out. Specifically, there’s a brief scene inside the tent when Indiana discovers Marion is still alive. This presents a clear choice: Take Marion and get the hell out of here, or keep her tied up so he can continue his pursuit of the Ark. What does he do? He continues his pursuit of the Ark. This proves that Indiana does have a flaw. His pursuit of material objects (his work) is more important to him than his relationships with real people (love). However, since this is the only true scene that presents this flaw as a choice, it’s the only time we really get inside Indiana’s head. Had we seen a few more instances of him battling this decision, I think Raiders would’ve hit us on an even deeper level.

Tune in next week when I dissect Indiana Jones and The Kingdom Of The Crystal Skull!