I checked out Captain America Brave New World this weekend, as it finally became available on digital. All in all, I had an okay time with it. As much crap as Marvel movies have received over the last four years, they bring something no there type of movie brings – which is high-budget feel-good entertainment – movie escapism at its best.

I also watched the A24 movie, Opus, about a journalist who visits a former pop star at his retreat only to learn that he’s running a cult, and while I also like that movie, it didn’t give me the feeing that a Marvel move does – that pure energetic infusion that makes you feel like a kid again.

Opus makes you feel confused, a little bit down, sad for the state of humanity. There’s nothing wrong with those movies but if all we had to watch were adult-themed films, we’d want to hang ourselves. Marvel is one of the few outfits that gives you a fun time at the movies.

With that said, Marvel has created a unique a screenwriting-related problem for itself that it doesn’t seem to have a solution for. I’m talking about STAKES. Stakes are the measured importance of what your characters are doing. Things have to matter for audiences to care about what your characters are doing. With Oppenheimer, for example, the fate of the world was at stake with the creation of the bomb.

This problem of stakes actually existed before Marvel popped up. It’s been an issue ever since George Lucas and Steven Spielberg invented the blockbuster back in the late 70s, and then eventually the trilogy. Lucas may have screwed all of Hollywood, in fact, when he came up with the Death Star. How do stakes get any bigger than a planet-destroying base?

Because, if you’re creating a sequel, you are tasked with upping the stakes. Otherwise, why would anybody show up to your film? Nobody’s really been able to figure out a definitive answer to that question.

In a way, the higher the stakes you create, the more you hamper your franchise moving forward. Cause you can’t top stakes that are already sky-high.

Marvel has had to deal with this on a whole other level, though. Because, unlike a trilogy, Marvel has a universe. So it doesn’t just have to figure out how to make the stakes higher in movies 2 and 3. It has to figure out how to up the stakes in movies 14, 15, 16, 17, 18. And what it’s learned is that that’s almost impossible.

I say “almost” because they found a momentary loophole – the gimmick of one-off all-star team-ups. Three Spider-Mans in one film for example. Or Deadpool and Wolverine. As far as consequences are concerned, neither of those films have high stakes. But the juicy team-ups distract us from that.

However, “juicy team-ups” is not part of any known writing formula. So you can squeeze 2-3 movies out of it. But, sooner or later, you have to go back to telling real stories without gimmicks. And that’s when you’re going to need stakes again. But you can’t create stakes if you’ve already given us movies with the highest stakes ever. I mean, the bad guy in the Avengers movies erased half the people in the universe.

Which brings us back to Brave New World. How do you make this movie work? What kind of stakes can you possibly introduce that will feel big enough to make us show up? Sure enough, they couldn’t. At “stake” is a brand new metal, called adamtanium, which is even more powerful than Wakanda’s vibranium. Not exactly snapping half of the universe away.

This is why nobody showed up for this movie. Avengers, Iron Man vs. Captain America, three Spider-Mans, Deadpool and Wolverine. Those movies destroyed any opportunity for Marvel to release a film like Brave New World. You’re asking the audience to show up for Taco Bell after serving them prime rib. Why would you think you could do that? It’s either arrogance or ignorance. I don’t know which. But you’d think there’d be somebody smart enough to know that audiences don’t show up for the understudy.

So, I pose a question to you. If you don’t have these giant stakes, what do you do as a writer? If you – as in you reading this article – were tasked with writing Brave New World, what would you do? Because there is, actually, a solution. And that solution is, you move the stakes over to the characters as opposed to the world.

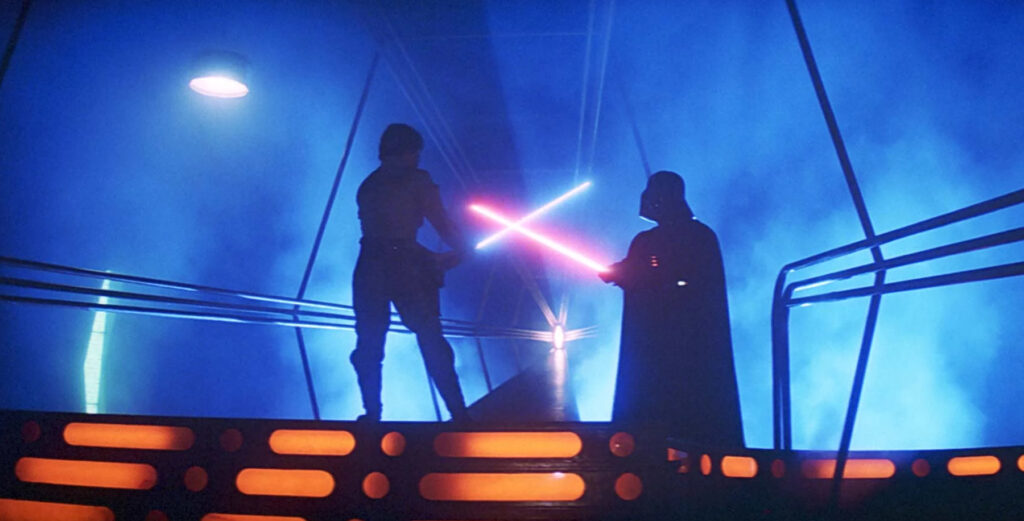

We actually see a successful example of this in one of the greatest franchises ever, Star Wars. In the second Star Wars movie, The Empire Strikes Back, there isn’t anything close to the magnitude of the Death Star. And yet many people consider Empire Strikes Back to be even better than Star Wars.

What can we learn from this? How did George Lucas pull a “lower stakes” movie off?

Well, he shifted the stakes onto the characters. It went from the importance of taking over the galaxy with this planet-killing base to defeating the character – Darth Vader – whose very existence allowed the Empire to control the galaxy. And, of course, the stakes were higher within Luke himself. He’s learning the Force, which threatens Darth Vader’s ability to rule the galaxy. So it is critical that Darth Vader defeat him.

This is what mid-tier (non team-up) Marvel movies ARE TRYING TO DO. This is what Brave New World is TRYING TO DO. It’s accepting that it’s not Avengers: Infinity War. But it’s trying to create characters that we care about and, therefore, become invested in, in the same way that high stakes make us invested.

The problem with that is, it’s hard to make characters do the heavy lifting in spectacle movies. Cause people come to spectacle movies wanting spectacle. And when you tell them, “We don’t have as much spectacle, but we’re gonna give you some neat characters instead,” it feels like a bait and switch to the average audience member. Cause Marvel has made them used to giant high-stakes spectacles.

And you can see just how hard it is when you consider that, in order for The Empire Strikes Back to pull it off, it needed 2 of the 5 greatest movie characters of all time in Darth Vader and Han Solo. How realistic is it that you’re going to write 2 of the 5 greatest movie characters into your movie?

I would go so far as to say Sam Wilson is, realistically, not even in the top 5000 best characters of all time. If your main character isn’t even in the top 500 best movie characters and you’re building your movie around character…. um, Good luck.

With that said, you still have to try. As a producer, you can’t walk into the Captain America writer’s room and say, “We know Sam Wilson’s Captain America isn’t a great character so we’re not even going to write him an emotionally compelling storyline.” No, you try. Because if you do pull a great character off, it will distract the audience from the fact that you don’t have gigantic stakes in your spectacle movie.

Where I think the Brave New World writers dropped the ball was in Sam Wilson’s internal struggle. What made Chris Evans’ Captain America intriguing was that he believed in doing the right thing no matter what. But sometimes he was presented with situations where doing the right thing no matter what could result in more damage than doing the “wrong” thing. So it was fun to observe that inner battle.

Sam Wilson didn’t have anything like that. Instead, they tried to lean into this idea that he’s taking the place of a beloved hero and trying to live up to that expectation, but that’s less relatable than the universal human struggle to choose good when constantly faced with temptations to do otherwise. In fact, after President Harrison Ford tells Sam Wilson that he’s not Steve Rogers, that was pretty much it when it came to that internal battle. They barely addressed it again. So, it obviously wasn’t enough.

To me, this is yet another reminder that old school screenwriting principles give you the biggest head starts in your script. Two of the big ones are: 1) create likable heroes and 2) give them interesting internal struggles that need to be resolved by the end of the movie. If you do those two things, you’re ahead of 90% of the screenwriters out there. And if you can add giant external stakes on top of that? Then there’s a good chance you’ve got a juggernaut of a script on your hands.

Okay guys, you’re going to hate me. But I’ve put off so many things that I have no choice but to take care of them this week. So I’m not sure I’m going to be posting much, if at all. I don’t have the time.

With that said, I wanted to leave you with my thoughts on the last two episodes in Black Mirror, Hotel Reverie and Eulogy. In classic Black Mirror fashion, one was the worst episode of the season and the other was the best.

What’s interesting about this is they both use the same type of concept, which reminds us how even a small change in the way a concept is approached can have an outsized effect on the quality of the story.

In Hotel Reverie, we follow a modern day movie star who is placed inside an old movie where she’s replacing the star. In Eulogy, we follow a man who’s placed inside old photos that bring back heartbreaking memories of his ex-girlfriend. In the former, nothing really makes sense. A movie star shows up to a new digital production and has no idea what she’s doing and they say to her, “You know all 500 of your lines by heart right?” And she’s like, “Uh, yeah,” and they then drop her into the old movie where she’s expected to say all those lines in one uninterrupted take. As if that makes sense. Not to mention she’s a black actress replacing a white male actor in a 1940s love story that I guess was going to be rereleased with her playing the new part. Like audiences would just accept that? Nothing in this episode made sense.

But Eulogy was really thoughtful and interesting. It follows this older man who has to go through old photos of him and his ex-girlfriend to find memories that they’re going to use at the now dead ex-girlfriend’s funeral.

The whole thing is this cool mystery as we go back from photo to photo, each one giving us a little more information on their relationship and what happened to make him so bitter with her. There are little twists along the way. And the ending is really good. It’s a wallop of an emotional punch. I recommend it to anyone who wants to see how to write a simple story out of a strong hook.

I will try to post again this week but I can’t promise anything!

I’ve watched four of the six episodes of the recently released seventh season of Black Mirror and, like all Black Mirror seasons, it’s a love-hate relationship. I don’t think I’ve watched something I’ve hated more than the first episode. In that one, a wife, Amanda, gets a traumatic brain injury and they digitally replace her brain under the condition that it be hooked up to a server that cost 300 dollars a month.

Everything’s great at first but then this service starts inserting ads (Amanda will randomly recite a commercial ad out of nowhere) and the only way to stop hearing them is to upgrade to the higher tier, at $800 a month. And then it keeps going up from there.

It’s not the worst idea in the world but the contrast between the marriage, which is played completely straight, and the service, which is played like it takes place in the Monty Python universe, is so jarring that nothing ever feels right. And the actors, Rashida Jones and Chris O’Dowd, who play the husband and wife, are beyond nauseating. If you had told me that the over-under for how many times two people could proclaim their love for one another going into this show was 500, I never would’ve thought it would hit the over. But they did! They’re trying sooooooooo hard to make you love them and all it does is push us further away. And Rashida Jones may be the single most boring actress who’s ever graced the screen. I absolutely hated this episode.

The next episode had zero pretense, zero satire. It was trashy. It was dramatic. And I loved it! This girl who works at a Bon Appetite like food company is thrown into disarray when a weird girl from her former high school starts working there. Soon, our heroine starts making mistakes that she’s never made before and suspects that her new coworker is responsible. But she can’t prove it. So she goes to extreme measures to take her down.

What I liked about this episode was that it proves you don’t need a ton to write a strong story. You really only need a good starting point (a solid premise) and some conflict. The heavier you can make that conflict, the juicier the story tends to be. And the writers here do such a good job creating the conflict between these two women. In the end, that’s all that was needed – two people going at each other and let’s see how this ends.

The third episode, Plaything, is the darkest of the four episodes I watched. It follows this strange older man who’s arrested by police under the suspicion that he’s responsible for a recently discovered suitcase that contains body parts in it.

The episode takes place mostly in an interrogation room at the police station and the two cops interrogating the man are baffled and frustrated when he tells them that all of this goes back to a video game he used to play 30 years ago – “The Throng.” The game consisted of the first digitally sentient beings in a game. These things understood their own existence. And they started replicating over the years, becoming a bigger and bigger civilization. As a result, he’d been tasked with growing the hardware over the decades so they could keep expanding.

But, finally, they’ve gotten too big for the hardware, which means there’s only one place left to expand – the internet. This, it turns out, was our older man’s plan all along. Get captured, come in here, and use a sleight-of-hand QR code trick to send the Throng into the UK’s governmental computer, via a nearby security cam. Soon, the Throng will be everywhere. And humanity will never be the same again.

If you know me, you know that I like when writers use common scenarios to build their scenes and stories around. I talk about this in my dialogue book. Common situations are your friend in writing. Interrogations, in particular, are fertile grounds to create interesting scenarios because the audience already understands the rules and these situations themselves are often high stakes, since murder is usually involved.

And you can see, with this episode, that as long as you inject that scenario with a fresh angle, you can still tell a fresh story. Interrogations very well may be 500 years old. But none of them have involved somebody talking about a video game that eventually becomes a threat to all of humanity. You take something old and you combine it with something new. That’s what makes it fresh (and that’s what’s made Black Mirror such a success).

The final episode I watched was the sequel to U.S.S. Callister. The U.S.S. Callister is considered by many to be the best episode of Black Mirror ever. It follows an evil coder, Robert Daly, at a game company, who digitally replicates his coworkers via a DNA-to-digital machine, which allows him to put their digital clones into his own version of the game, where he can then lord over them like a God.

In this sequel to the original, the New York Times has gotten wind of a rumor about the digital clones. If true, it would sink the company. So the president tasks one of his coders, a young woman named Nannette, to figure out what’s going on. When Nannette learns that her own digital clone, as well as five others, are in the game, she must figure out a way to save them. Meanwhile, the digital clones are in the game fighting off real players. The difference between them is, if the players die, they can just respawn. If a digital clone dies, they die for good.

For the most part, I enjoyed this sequel. However, it’s a reminder that the more complex the rules are, the harder it is for the average reader/viewer to keep up. I’d forgotten the rules from the original movie, and it took a good 45 minutes to remember how it all worked. Basically, it was hard to track the exact connection between the real world people and their digital clones. How much did they know about each other? How did they communicate?

I always tell writers to keep your sci-fi rule-set as simple as possible. Most writers enjoy getting into the weeds of their rules and, in the process, we, the reader, get left behind. This just happened recently. I read a sci-fi script with way too many rules and it, ultimately, took the screenplay down.

At the very least, if you have a lot of rules, you have to be awesome at explaining them to the reader in an understandable way. That’s where you see the biggest difference between pros and amateurs. Despite some of my issues with the excessive rule set here, I ended up understanding them by the end and, in most amateur scripts that tackle rules this extensive, that wouldn’t have happened.

Ultimately, I think the movie suffers from Cristin Miloti carrying the load. She’s great to look at but she is nowhere close to being able to carry a movie all on her own. She’s just not interesting enough as an actress. The reason that first movie was so good was 50% due to the writing and 50% due to Jesse Plemons. Without Plemons playing a major role here, the sequel doesn’t compare to the original.

But it’s still solid. What did you guys think?

I’ve been dropping in on the various post-White Lotus interviews to get more context on the season. I don’t like to do this at the beginning of a show because I feel like I might stumble across spoilers. But at the end of a show, especially one I love, I want to know everything I can about it.

So, I want you to think about your journey as a writer and why you’re doing this. I want you to imagine what it might look like if you’re super successful. If it’s anything like what *I* would imagine, I would say that Mike White is experiencing the pinnacle of what success looks like as a screenwriter.

He’s got the most talked about show in the world at a time when it’s harder than ever to stand out in television. Despite the massive success he’s found through the first two seasons of White Lotus, the third season is even bigger, becoming a bona fide phenomenon. The finale tallied a 30% increase over the second season’s finale. And the show has become a social media juggernaut, spawning more memes than a presidential election.

So I was surprised when I began listening to Mike White’s recent interviews and noticing that he didn’t sound happy. He seemed jostled by some of the show’s criticisms (that the plotting was too slow, that there were no police scenes after the giant shootout, that Lachlan would make a smoothie without cleaning the blender first), and he ended up telling Howard Stern he needed to “get away from all this for awhile.”

This both terrified and fascinated me. Here this screenwriter is, experiencing the pinnacle of what it’s like at his profession, and he’s not happy. If there’s anybody who should be ecstatic about a writing accomplishment, it should be Mike White. Yet here he is getting riled up about these criticisms people have with his mega-successful multiple-award-winning show.

The more I thought about this, the more I realized that screenwriters are an unhappy lot. They’re always complaining. They’re always frustrated. And they always think that the next hill they’re able to climb will solve their happiness problem.

They think, if I can just get an agent, I’ll be happy. But then they aren’t because they learn agents are not magicians. So they say, if I can just sell something, I’ll be happy. But then they aren’t because the money they receive only goes so far. So they say, if I can just get something produced, I’ll be happy. But then they aren’t because a lot of the show/movie gets rewritten and the product ends up subpar. So they say, if I can just make something that gets a lot of critical acclaim, I’ll be happy.

And that’s the one you’d think would be impossible not to be happy about. But guess what? Mike White shows that you can still be unhappy when you get to the top of the screenwriting mountain! Because when you make something critically acclaimed, you face a new obstacle – expectations. And you’re never going to be able to make everyone happy. So if your goal is to have every single person love your show, you will never ever ever be satisfied.

Why do I bring this up?

Because artists are, sadly, predisposed to being miserable. Especially writers. And if we’re never going to celebrate our wins, what’s the point of doing this? If you’re going to be just as frustrated with a giant hit show as you are “only” getting to the second round of the Nicholl Screenwriting Contest, then why even bother?

The truth about screenwriting is that there is no such thing as a perfect script. Because in order to write a great script, you must sometimes do the “wrong” thing. You must sometimes write an unlikable protagonist. You must sometimes write on-the-nose dialogue. You must sometimes have a character do something that a real person wouldn’t do in real life, like make a smoothie without cleaning out the blender first. And all of these things are technically going to make your script “imperfect” but that’s what makes the script great! It’s that splash of imperfection.

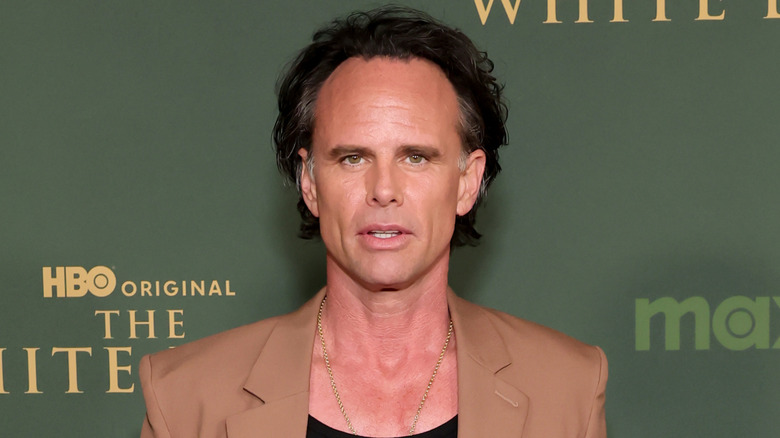

Scripts are like people. The most interesting ones have flaws. If a script is “perfect,” it’s like looking at someone who’s had 15 cosmetic procedures on their face. Sure, their face is “perfect,” but that person is never going to be as interesting to look at as, say, Adrian Brody, with his big nose, or Amie Lou Wood, with her funny teeth, or Walton Goggins, with his adventurous hairline.

You don’t want to purposefully aim for your scripts to be imperfect but you want to follow your heart when you write and trust yourself that it’ll be okay. As long as those imperfections are contributing positively to the overall story, you’re good.

One of the criticisms that Mike White seems to have taken offense to the most is his handling of the shootout and the way the bodyguards acted (they originally chased after Rick then easily gave up). Was it perfectly done? No. But you know what? I thought nothing of it at the time. I only found out afterwards that people had issues with it.

White actually talks about it. He says he doesn’t do gunfights in his films. His films are always character-driven. So it was not something that he was very good at.

You wanna know why I thought nothing of it at the time? Because I was invested in the characters. That’s what Mike White knows that not enough writers know – if you get the characters right, the majority of viewers/readers will not care about your errors. 1) Create interesting characters with flaws that arc over the course of the story. 2) Create interesting relationships with the other characters that contain conflict that needs to be resolved. If you do those two things, 99% of people won’t care that the shootout was sloppy. From everything I saw on social media, the parts of that scene that fans focused on most were the tragic death of Chelsea and how Laurie comically sprinted away from the shootout like a bat out of hell. They focused on the character stuff.

Look, if people are talking bad about your script? If people are talking bad about your show? THAT’S GREAT. That’s all that matters. Because the worst thing that can happen when you release a show or movie is not that you get some criticism. It’s that NOBODY CARES. Nobody talks about your show at all. Did anybody here know they made a TV adaptation of the movie, Cruel Intentions? Yeah, they had a full season of it. Did you know that? No. Nobody does. Because nobody talks about that show.

THAT’S the worst thing that can happen. If people are complaining about your show, it means they care!

I guess I’m sad that Mike White is sad. This should be the happiest time of his life. And I feel like so many people in this business are like him. I just met this fitness influencer who recently gained a ton of followers on social media and she was telling me how upset she was about various issues that had come up with her success (more haters being the main one). And I’m thinking to myself, “You’ve got one million followers. If you can’t be happy about that, when are you going to be happy?”

Guys, writing is supposed to be fun. That’s why we got into it. If you’re unhappy, you’re probably focusing on the wrong things. Instead, shift your focus to the fun of telling a story – of coming up with a great character, or setting up the perfect payoff, or coming up with that amazing plot twist, or writing a great scene. And be kind to yourself. Celebrate the wins.

When your script is done, put it out there, hope for the best. But don’t tie your happiness to whether people like your script or not. You just can’t predict how people will react. If people love it, great. Ride that wave as long as you can ride it. But if they seem indifferent, you’re a writer. Come up with a new idea and write THAT. That’s what you do.

The quickest way to give up in writing is to become bitter and angry about it. Don’t do that! Write stories because you love to write stories and that way you’ll be happy at every stage of your success.

Genre: Drama/Sci-Fi

Premise: A woman begins dating a perfect handsome man only to discover that he may not be human.

About: Today’s screenwriter, Kate Folk, authored the short story collection, Out There, which today’s script is based on. She has written for publications including The New Yorker and the New York Times Magazine. She was also a Wallace Stegner Fellow in fiction at Stanford University. The script appeared on last year’s Black List.

Writer: Kate Folk

Details: 111 pages

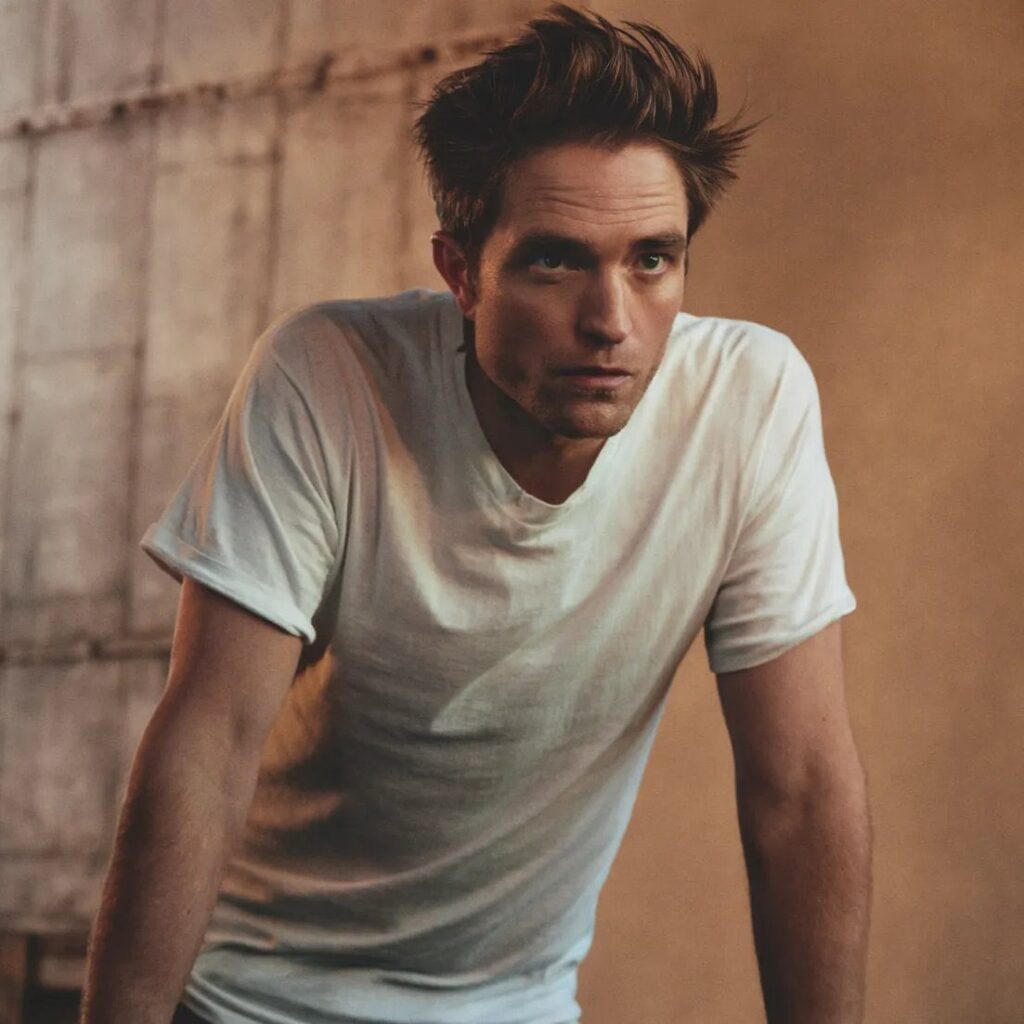

Pattinson for Roger?

Pattinson for Roger?

It’s appropriate that Black Mirror comes out with a new episode this Friday because today’s script is less a feature film than it is a storyline for a Black Mirror episode. Let’s see if it’s any good.

Normal-looking Alicia and newish drop-dead gorgeous boyfriend, Alan, have just spent an amazing night in a cabin in Big Sur, a picturesque resort town on the northern coast of California. While Alicia sleeps, Alan gets up, props open Alicia’s laptop, and his eyes go milky. Seconds later, the laptop dies. He does the same with her phone. He then walks over to the window, dissolves into a ball of energy, then dissipates.

Cut to a week later where we meet San Francisco eye-surgery tech, Meg, who is still hurting after getting dumped by her boyfriend, Matt. Although Matt was, by no means, perfect, he’s a lot better than all the losers she’s been dating on these dating apps. She not-so-secretly yearns to jumpstart their relationship again.

And she gets her chance when she arrives home one night and Matt is at her apartment, talking to her passive-aggressive roommate, Genevieve. Matt is happy to see Meg and asks her if she wants to be his ‘plus-one’ at a work dinner event. She doesn’t have to think twice.

When she shows up at the dinner, Meg is upset to learn that she won’t be sitting with Matt but, rather, a group of random people at a table. She’s ready to explode until she meets the guy she’s sitting next to – the gorgeous perfect gentleman, Roger. Roger is instantly smitten with Meg, which throws her off. Guys this handsome don’t usually pay her attention.

Soon the two are texting each other, talking all the time, going on dates. But it doesn’t escape Megan that Roger is kind of… odd. He’s overtly formal in the way he speaks. He’s way too polite. He seems to have zero concept of how handsome he is. And he quadruple texts! Everybody knows, on the dating scene, that it’s suicide to even DOUBLE TEXT. So clearly something’s not right.

Soon, Roger is pushing Meg to go with him to Big Sur. Everything is “Big Sur, Big Sur, Big Sur.” He’s pushy enough that Meg is cautious. And that’s when the story breaks. Alicia, the woman from the opening, reveals her story to the news – which is that some shady Russian tech company has created AI men who are designed to lure in unsuspecting average women, take them to Big Sur, then steal their entire digital lives (identity, bank account, job, etc).

At first, Meg is mortified. But when these men – known as ‘blots’ – start getting arrested across town, Meg feels bad for Roger, and continues to see him, even providing him safety from the authorities. When it becomes clear that Roger’s programming is geared towards climaxing at Big Sur, Meg decides to go with him, understanding the consequences. She prepares all of her data for its inevitable theft, but has she prepared for everything?

I used to think that “voice” was all about the way your characters spoke—that the offbeat sense of humor you gave them made up 90% of your voice as a writer. Think John Hughes, Diablo Cody, or Quentin Tarantino.

But I’m starting to realize that it’s more complicated than that. Voice begins with the type of subject matter you choose to encase your story in. For example, if you’re into car chases and shootouts and you write your scripts accordingly, those are pretty broad topics. They appear in a lot of movies. So someone who writes about them won’t be seen as a “unique voice.”

Meanwhile, if you write about professional apologizers (these are real people in Japan), that subject matter is much more niche and allows your story to stand out amongst others. It is the starting point for creating a unique voice.

Also, any movement into fantasy/sci-fi is an opportunity to isolate your voice from others. Here, Folk has created these entirely AI human beings that disappear into balls of energy once their mission is accomplished. Again, that’s a very niche idea and, therefore, helps form a specialized voice.

Once you mix in how you see the world, your voice as a writer really starts to stand out. Maybe you see humanity through the lens that people are inherently good and eager to help one another. Or maybe you see it as everyone being selfish, always looking for an angle or a way to take advantage. Either perspective can shape your storytelling.

You can also dive into the nitty-gritty—like how your characters approach dating. The way someone sees the dating world has a huge impact on how their story feels. Are they hopeful? Hopeless? Do their characters take whatever they can get, or do they never settle? Whatever angle you choose to highlight usually reflects how you see dating, and that perspective becomes a key part of your voice.

To summarize, if you can mix a series of offbeat viewpoints together, you can really stand out as someone with a unique voice. Which is why I think Kate Folk is one of the better writers on last year’s Black List. Because while her story itself isn’t very sexy – it’s basically about a relationship – all of these unique ways in which she sees things give the script an unusual tenor. It’s covering a basic human relationship yet it doesn’t feel like something we’ve read before.

Now, I didn’t say that meant it was good. There isn’t enough plot here. But there’s enough to keep us engaged. I thought one of the more interesting creative choices Folk made was to expose Roger at the midpoint. Most writers would’ve kept the dramatic irony going – where we knew Roger was bad but Meg didn’t – all the way to the Big Sur climax.

But, instead, Folk uses that plot development (blots are exposed) to alter the story. Now it becomes a riff on Steven Spielberg’s “A.I.,” where Meg is harboring Roger and decides she wants to help him complete his purpose. While I wished there would’ve been higher stakes for Meg, the stakes are still high enough on Roger’s end (he’s going to die) that the climax had weight.

If you’re looking for how to write a script that hits people viscerally, like yesterday’s Bato Bato, this script is not for you. But if you’re trying to find ways to better express your unique sensibilities through your screenplays, you’re going to want to check this out.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Here’s Kate Folk on how to approach writing first drafts – “I find first drafts challenging and, actually, I prefer the revision stage, because it seems so daunting to create something out of nothing. My strategy for that is to pour as much content on the page as I can, so that then I have something to work with and transform from there.” I agree. When you’re struggling to get your script out, drop the judgment and just put words down on the page until you finish. It won’t be perfect but at least you’ll now have clay that you can start molding.