Genre: Period/Supernatural

Premise: (from Black List) A young slave girl named Lena has telekinetic powers she cannot yet control on a plantation in the 1800s.

About: This script finished on last year’s Black List. The writer, Sontenish Myers, an NYU grad, received the Tribeca Film Grant to make the film. The Tribeca Film Grant provides film budget grants for under-represented groups.

Writer: Sontenish Myers

Details: 114 pages

The other day I was talking to someone who is not in the screenwriting world. They like movies but they’re by no means obsessed with them like you and I are. Anyway, she was curious about my job, particularly when it came to deciphering the difference between a good script and a bad script.

“It’s all subjective, right?” She said.

This is not the first person I’ve run into who believed that the only difference between one script and another is the subjective nature of who reads it. The variable these people never consider is that a script must meet a basic standard of quality before it can be judged subjectively against other scripts. If it has not met that standard, then it is objectively not as good as other professional screenplays.

I don’t know if everyone here remembers Trajent Future and his bullet time dreams. But that classically bad amateur script was objectively worse than its professional brethren.

The question I then get is, how do you objectively know the difference between a beginner script and a professional script? Well, that answer is long and varied because there are a lot of things one must learn to write a professional-level script. But we’re going to go over a couple of ways to spot a problem script today to give you a feel for how readers assess these things. Let’s take a look.

The year is 1802 and 11 year old Lena is a slave on a cotton plantation with her mother, Alice. We learn early on that Lena can make things levitate. Like bottles or buckets of water. As a kid, she has fun with the power despite the fact that her mother keeps reminding her that if anybody finds out about this, they’re dead meat.

One day the decision is made to bring Lena inside and make her a house slave. So she and her mother are split up. Lena then tries to befriend all the other house slaves (all of whom are older) to mixed results. She also struggles to keep her telekinesis under control.

Then, one day, when she’s out getting water, a mysterious black woman approaches her and takes her back to her secret underground home. She’s seen Lena use her powers and wants to help her hone them. This interaction leads to the best exchange in the script. “Why do you live down here?” “Down here I’m free, up there I ain’t.” “Freedom is a lot smaller than I thought.”

In addition to Lena’s weekly telekinesis lessons, she also finds a 14 year old slave – Koi – who ran away from a neighboring plantation. Lena introduces Koi to the mysterious underground witch woman who feeds him and prepares him for his next journey.

After weeks of daily chores and strengthening friendships with the other house slaves, Lena’s worst nightmare comes true – her mother is sold. Lena slips away to Koi and the Telekinesis Witch and demands that they do something – use their powers to get her back. But will the two help Lena? Or do they consider the task too risky?

“Stampede” is an example of a common beginner concept mistake. A writer will give a character a power and believe that that power has given them their story. Unfortunately, it doesn’t work like that. Giving Lena telekinesis doesn’t give you a screenplay. All you’ve done is give your character a trait, not unlike the ability to play baseball or be a really good businesswoman. What about your story? What is going to happen that will make that trait interesting? That will put that trait to the test? Most beginner writers don’t know the difference between the two and therefore cobble together a disjointed narrative while occasionally going back to the power in the hopes that it will do some heavy story lifting.

Look at Get Out. The beginner screenwriter version of that is a black man dating a white woman. That’s it. The writer hasn’t thought beyond that. But the veteran screenwriter knows that all he’s done is set up the characters. He still has to come up with a story. So he adds that the girl is taking the boyfriend to meet her parents for the weekend and something bad is going on at their home. We never get anything like that in Stampede. It’s a narrative with no singular focus.

To be honest, I think this script would’ve been a thousand times better without telekinesis. The telekineses only serves to distract from the more poignant story about a young slave. It also makes the reader keep waiting for the telekinesis to become a bigger part of the story. And since it’s only a minor component, we never get that payoff. That makes the power a story distraction rather than a story ally.

Also, it seemed like there were better directions to take the story. But, in another common beginner mistake, the writer always took the path of least resistance – the path that made it easiest to write. You want to do the opposite. You want to go in those directions that are scary for you and harder on your character. If the slave owners would’ve discovered Lena’s powers, for example, maybe they try to use them for their own nefarious goals. Teaming up a slave and slave owners is where you’re going to find those messy but more interesting storylines.

But the biggest problem with the script is that the narrative isn’t purposeful. There is no goal. There are little, if any, stakes. And there’s definitely no urgency. Combined with the fact that the hero is stuck in one location, the story feels passive. There’s nothing for the characters to do. This leads to the writer coming up with all these small side stories, like the witch, like the 14 year old slave boy, like the friendships with the other slaves, that have no narrative thrust. There are no engines beneath these stories so whenever we’re participating in them, we’re asking ourselves what the point is.

How do you give a script narrative thrust? Simple. You create a big goal with high stakes attached. At around page 90 in this script, Lena’s mother gets bought by another slave owner and taken away. I’m not going go into some of the ancillary problems with this plot choice (we hadn’t seen the mom for 65 pages so we didn’t feel anything when she was sold). But what you could’ve done that would’ve been a lot better for the plot is to have the mother bought on page 25, the event that forces Lena to be moved into the house. Now you have a clear goal – Find and reunite with her mother again. It really is as simple as that. And that doesn’t mean you have to send her off on the journey. The entire movie can be her planning her escape and how she’s going to get to her mother and then the final act is her executing the plan.

Finally, you need your super-power to connect to your story better. Or else it just feels random. And that’s how this power felt. What does lifting bottles up have to do with anything in this subject matter? There’s literally zero connection – plot wise or theme wise. This tends to be another beginner mistake. The young screenwriter gets so hung up on the thing that they personally think is cool (in this case, telekinesis), that they never consider whether it’s relevant to the story they’re actually telling.

Last week, with The Paper Menagerie, the mother character had the power to make origami animals that came alive. That power had a ton to do with the story. It was cultural. It was the only way she knew how to connect with her son. They were a poor family so those animals were the only toys he had. They were also his only friends. And the animals ended up having messages within them that gave us our surprise ending. In other words, the power was organically connected to the story. We never got that here.

This script was just way too messy for me. I’m kinda shocked it made The Black List.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Period stories tend to work best when they’re set during a time of transition. All I could think while reading this was how much more intense it would’ve been had it been set in the months leading up to the end of slavery. The slave owners would’ve been more on edge. There’s uncertainty in the air. There’s more anger and, therefore, more potential for violence. This script was definitely missing an edge. That could’ve provided it.

Genre: Sci-Fi

Premise: An archeologist father and his young daughter must attempt to decipher an ancient alien message on a distant planet.

About: This is the big package that is bringing back a lot of the same team from “Arrival,” as this is another thinking man’s sci-fi story. The short story comes from Ken Liu. Shawn Levy of 21 Laps is the one who purchased it.

Writer: Ken Liu

Details: Short story about 15,000 words (an average screenplay is 22,000)

I’ve been all over Ken Liu since reading his amazing short story, The Paper Menagerie. When I heard he’d be teaming up with the new king of Hollywood, Shawn Levy, to adapt his short story, The Message, into a movie, I couldn’t remember any project announcement that got me more excited this year!

But one thing I’ve realized as I’ve studied Ken Liu is that he’s realllllyyyy smart. Intimidatingly so. Check out this answer he gave in a recent DunesJedi interview regarding his approach to science fiction versus fantasy…

“I think of all fiction as unified in prizing the logic of metaphors over the logic of persuasion. In this, so-called realist fiction isn’t particularly different from science fiction or fantasy or romance or any other genre. Indeed, often the speculative element in science fiction isn’t about science at all, but rather represents a literalization of some metaphor. I like to write stories in which the logic of metaphors takes primacy. My goal is to write stories that can be read at multiple levels, such that what is not said is as important as what is said, and the imperfect map of metaphors points to the terra incognita of an empathy with the universe.”

I’ll have to get a doctorate in Smartness at MeThinkGood University before I’m fully able to digest all of that. But the parts I did understand speak to one of the debates we’ll have later on. “The Message” has a lot of pressure on it as it’s coming after the perfection of The Paper Menagerie. Let’s see if it delivers.

Our story takes place in the way-off future. Our narrator, an exo-planet archeologist, flies around the galaxy to ancient civilizations in order to learn about extinct alien races. They’ve found a lot of these civilizations. But, so far, nobody has been able to find a LIVING alien race.

Just before he’s about to explore his latest planet, the narrator learns that his wife has died and he must now take care of their 11 year-old child, Maggie. He’s never even met Maggie so how do you say “awkward” in archeology-speak? Due to the fact that they’re going to blow up the latest ancient civilization planet soon, the narrator doesn’t have time to drop his daughter off and must bring her along.

Together, the two walk around the pyramid-infested city, which died off over 20,000 years ago. Their goal is to decipher “the message.” There are a lot of hieroglyphics everywhere and he’s convinced they’re all trying to say something. With the help of Maggie, who’s also into archeology, they do their best to decipher all the mysterious pictures.

Meanwhile, Maggie passive-aggressively needles her father about prioritizing his work over staying with the family and raising her. Why the heck does he care more about long-dead alien civilizations than his own family?? It’s a good question that takes a back seat when the dad finally cracks the message (spoiler). The message is that this is a highly radioactive area. Stay away. Stay away. Stay away.

This means they are both dying quickly. The dad can put Maggie in stasis which will halt the radiation poisoning until they get her to a hospital. But since the ship was damaged during landing, the dad will need to manually fly it back up into the atmosphere. By that point, the radiation poisoning will have reached a point of no return. He’ll die. Which means that just as this father-daughter relationship was about to get started, it’s already over. The End.

You would think ancient alien civilizations would be ripe subject matter for a movie. A sweeping shot of the long dead alien city alone is a money shot for your trailer. And yet the last two Alien movies proved that maybe ancient alien civilizations aren’t as cool as we thought they were. And this latest dive into the subject matter isn’t giving me a lot of confidence that that trend won’t continue.

Then again, Liu always seems to be more interested in the human element of these stories than he does the science element. If the character stuff works, it’s going to make the ancient civilization plot work by proxy. Unfortunately, the character stuff doesn’t work. Which is surprising considering that Liu wrote such a great parent-child storyline in The Paper Menagerie.

Today’s story proves that there’s a razor thin line between emotional effectiveness and melodrama. When the emotional component is working, it’s like magic. Our stories seem to come alive right from under our fingertips. When it’s not, it’s frustrating because you’re never completely sure why. It *should* work. A dad and the daughter he’s never met before are forced to team up to solve a puzzle. She doesn’t like him. He doesn’t understand her. The subtext writes itself.

However, something about this relationship feels on-the-nose compared to Menagerie and therefore never connects with the reader. I think I know why. If you look at The Paper Menagerie, the mother-son relationship was built around a very specific issue – she refused to speak English. He refused to speak Chinese. The story was about lack of communication. It was specific.

The Message doesn’t have that. There isn’t a specific problem in their relationship. It’s general. He ran off on his family so this is the first time they’re together. General is derived from the same tree as Generic. When you generalize in storytelling, you are often being generic. That’s what this felt like. Your average generic daddy who has to take care of a daughter he never knew he had story. Hollywood comes out with five of these a year. So if you don’t work to specify the relationship in some way, like Liu did with Paper Menagerie, the story is never going to take off.

More importantly, the emotional beats aren’t going to have the same oomph. This is why it’s so easy to shoot for a big emotional scene only to have the reader rolling their eyes.

Getting back to what Liu was talking about in that interview, he says that fictional writing should be all about the metaphors. I’m not sure I’ve heard an author say that before. I suppose it could be a short story thing. But I got the impression he was talking about all fiction. I vehemently disagree with that approach.

I got the sense that this ancient civilization had a metaphorical connection with the dad’s fractured relationship with his daughter. But I couldn’t make out what that connection was. Maybe someone can help me out. But even if I did understand the metaphor, it would not have made me connect with these characters any better. It would not have fixed the fact that the plot is basically two people walking around an empty city the entire time. Those are genuine story weaknesses that could’ve been improved if the focus was more on the storytelling and less focused on metaphor.

I’ll go to my grave saying that telling a good story should be the priority of every script you write. If you want to win new friends in your English class, go metaphor-crazy. But if you want to write a story that people actually enjoy, focus on the storytelling. Drama. Suspense. Irony. Unresolved Conflict. Problems. Goals. Obstacles. Stakes. Inner transformation. Urgency. And here’s the catch. You have to do all of these things IN A WAY THAT’S NOT DERIVATIVE. The story, along with the elements within the story, have to feel fresh and specific. The Message didn’t pass that test.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Work vs. Family is one of the most powerful character flaws available to writers. This is because it’s such a universal flaw that everyone understands. Even if you don’t yourself have the flaw, chances are there’s someone close to you who does. Which means you understand it. That’s what you’re looking for with character flaws. You’re trying to find flaws that all human beings can relate to. Here, the father chose work over raising his child. Liu didn’t nail the execution (in my opinion) but I still see this character flaw working in a lot of stories. I know writers often struggle to find a flaw for their main character. Well, this one is one of the easier flaws to show and execute as a character arc. So keep it in the hopper.

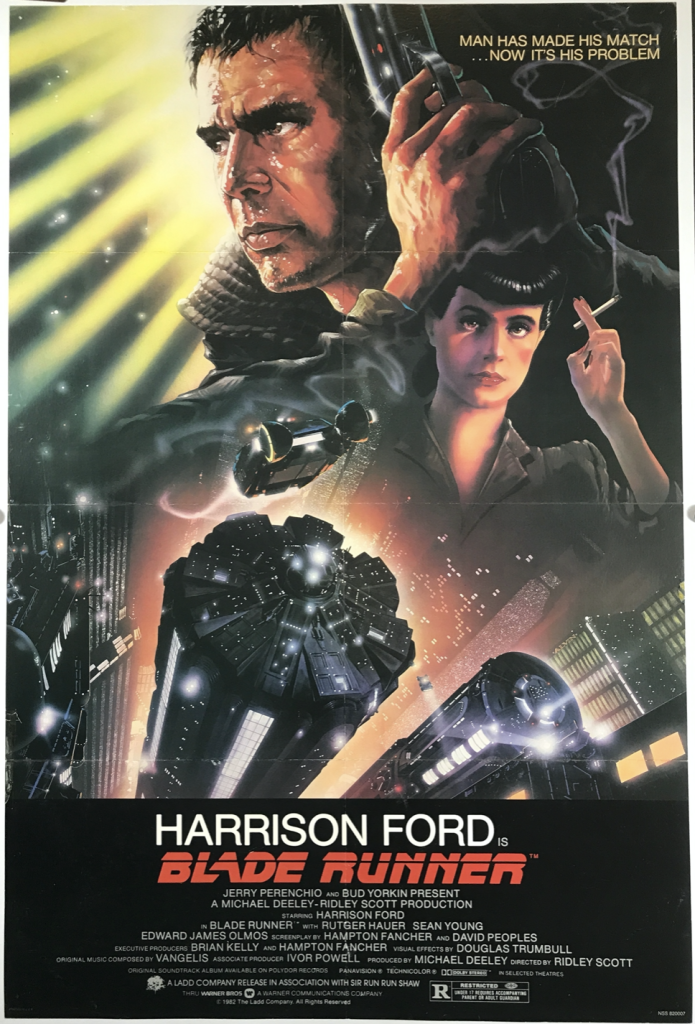

Titles are one of the most under-analyzed elements of screenwriting. That’s because titles don’t truly become important until the movie is being marketed. And since titles are only a few words, potential script buyers know they can easily change them. However, a good title can make a great first impression, getting a reader excited before they’ve even opened up your script. A *great* title can even get someone to greenlight a movie (as it famously did with the title, “Monster In Law”). So it’s worth carving out some time to come up with the best title possible. Here are a few all-timers…

Cool Hand Luke

No Country For Old Men

Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind

Slumdog Millionaire

The Devil Wears Prada

One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest

Things to Do In Denver When You’re Dead

Blade Runner

Apocalypse Now

Kill Bill

Inception

Trainspotting

Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy

Full Metal Jacket

The Last Picture Show

Jaws

Back to the Future

Dude Where’s My Car

Midnight Cowboy

To Kill A Mockingbird

Touch of Evil

On that note, I’ve found that talking about titles in the abstract doesn’t do much for screenwriters. In order to understand what makes a title good or bad, you need to SEE the title. So what we’re going to do today is look at 25 titles from The Last Great Screenplay Contest and I’m going to give each of them a 1-10 rating, as well as some insight into how I came to that rating. I’m also going to include the genre because you can’t really get a feel for a title unless you know the genre.

By the way, if your title shows up here and I give it a poor rating, that has no bearing on whether I liked your script or not, as I’ve gone into every script so far only focused on the first 10 pages. Today’s article is about titles and titles only. Feel free to share your thoughts about each of these titles below and how you’d rank them. Let’s get to it!

Title: We’re Doing Just Fine

Genre: Black Comedy

Analysis: Solid title. It’s not going to win any awards but the combination of the genre and the irony of the title (“Just” conveys that they’re doing anything but fine) imply that the writer gets comedy. To see how this title could’ve gone south, look what happens when we give it a more straightforward treatment: “We Are Not Doing Fine.”

Rating: 7 out of 10

Title: Out of Time

Genre: Time Loop/Thriller/Action

Analysis: “Out of Time?” Really? Come on!!! A time loop thriller titled, “Out of Time?” You couldn’t come up with anything more original than that?

Rating: 2 out of 10

Title: The Commune

Genre: Contained Horror

Analysis: The problem with titles like this is that they imply you’re not tuned into the business you’re trying to break into. I think there have been a dozen movies titled, “The Commune.” I’ve probably personally read 20 scripts titled, “The Commune.” It’s a very very common title. It’s your job as a writer to know this because I guarantee you every industry person you send this title to is going to dismiss the script based on its generic nature.

Rating: 2 out of 10

Title: BIG TROUBLE IN BRECKENRIDGE

Genre: Action/Sci-Fi & Fantasy

Analysis: You want titles like this to have some contrast, some fun. Look at its inspiration: Big Trouble in Little China. See how much better that reads with the contrasting of the words “Big” and “Little?” Overall, the title inspires more of a visual than most of the titles today but it’s random and not very well thought out.

Rating: 5 out of 10

Title: The Good People

Genre: Horror

Analysis: A fairly decent title. Maybe a teensy bit too bland? But I could see this inspiring some reads with a good logline.

Rating: 6 out of 10

Title: Way

Genre: Drama/Romance/War/Historical/Action

Analysis: There’s information. There’s not enough information. And then there’s this. “Way?” This title literally feels like a mistake was made – that the writer was in a rush and mistakenly forgot to put the whole title in. Yikes.

Rating: 1 out of 10

Title: Candyflip

Genre: Drama/Thiller

Analysis: Easily one of the most original titles submitted. Gets you thinking. Wondering what the movie is about, which is good. I’m a little thrown by the “drama” tag. If this was a straight thriller or action movie, I think the title would work even better. But definitely one of the best on this list.

Rating: 8.5 out of 10

Title: When Tomorrow Starts Without Me

Genre: Thriller

Analysis: I like this one! It definitely gets you thinking, which is always good. Why would tomorrow start without our hero? There’s a mystery there I want to know the answer to.

Rating: 7 out of 10

Title: Tigers

Genre: Thriller

Analysis: I’m going to break my code and provide a little insight on this one. It’s got a really good premise and it made it into my “Maybe/High” pile. “Tigers” doesn’t tell us nearly enough about this story. It’s just too darn generic and doesn’t provide the level of curiosity a good script like this deserves.

Rating: 3 out of 10

Title: A Violent Noise

Genre: Drama/Action

Analysis: Too obvious. When you think “noise” you think loud, so a “violent” noise isn’t that far off. Which smacks of redundancy. Look for contrast in these types of titles. “A Violent Whisper” feels like a title I’ve heard before so I’m not claiming it’s amazing. But it’s definitely better than the on-the-nose “A Violent Noise.”

Rating: 4 out of 10

Title: The Arcanum

Genre: Fantasy/Action

Analysis: It’s a fantasy-sounding title. So I’ll give it that. But it loses points due to the fact that I have no idea what an “arcanum” is.

Rating: 5 out of 10

Title: Lotus

Genre: Psychological Thriller

Analysis: On the plus side, intriguing mysterious single-word titles can work. Especially in genres like horror, sci-fi, and psychological thriller. The trick is picking a word that is genuinely intriguing but also original. Hard to do. I think that’s where “Lotus” stumbles. It uses a word that has me intrigued. But I feel like I’ve seen too many titles like it before, which puts it in the good but not great category.

Rating: 6.5 out of 10

Title: Dark Lands

Genre: Action/Fantasy

Analysis: Easily up there with one of the most generic titles you can come up with for a fantasy film. Fantasy is one of the more imaginative genres out there. You need to give us a title that displays some level of that. Let’s get that imagination going, man. Not use something from Tolkien’s trash bin.

Rating: 2 out of 10

Title: Dolly

Genre: Horror

Analysis: One of the more effective things you can do with a title is to juxtapose it with your genre. That’s what we’re doing here. “Dolly” is a positive, almost jovial, word. So when it’s contrasted against horror, it creates intrigue. Conversely, if your horror script is titled, “Axe Murderer,” that’s pretty darn boring.

Rating: 7 out of 10

Title: Goodnight Nobody

Genre: Contained Thriller/Horror

Analysis: If we’re going on title alone, I’m not sure I get this. Maybe it’s a play on “Goodnight everybody?” I think that’s a phrase. But the turn-of-phrase doesn’t play off the original phrase organically enough to feel clever. – Now, I also happen to know that this script is about snakes. Why you have a script about snakes and don’t imply that anywhere in your title, I don’t know.

Rating: 3.5 out of 10

Title: Skin

Genre: Sci-Fi

Analysis: This is one of those rare occasions where the sparse, almost innocuous, title works perfectly in conjunction with the genre to imply something cool. Skin can imply so many things in the sci-fi genre, both literal and metaphorical. So I’d give this title a positive grade.

Rating: 7 out of 10

Title: Getaway

Genre: Horror/Thriller

Analysis: It’s not the worst title. The word “getaway” implies characters taking action, which is always good for movies. It creates an image in the reader’s head of what the movie is about. But I think I’d tell the writer, is this the best you can do? Yeah, it’s solid. But there’s definitely an unimaginative quality to it. Here’s a pro-tip for everyone. With movies, the title doesn’t have to be as splashy because it’s being displayed along with the trailer, or along with a billboard. So we have additional visual context to what the movie is about. With a script, you don’t have that. So it’s in your interest to come up with something that grabs the reader.

Rating: 5 out of 10

Title: The Little Friend

Genre: Horror

Analysis: This is one of the weaker titles I received. It doesn’t provide any working visual in my head of what the movie is. It actually achieves the opposite. It makes me think of weird things like a friend who’s 18 inches tall. If this was a comedy, that would work better. But it’s a horror film. And nothing about this title scares me. Make sure you’re thinking about the image your title is putting into the reader’s head.

Rating: 1 out of 10

Title: Hexagram

Genre: Action Horror, Supernatural Thriller, Contained

Analysis: Ahhhh! The dreaded triple-genre genre. Stay away from triple genres, people! Two at most! This title is just boring. I’ve come across hundreds just like it. Pentagram, Hexagram, Octagram. Well, maybe not Octagram. But you can be a lot more imaginative than using “Hexagram” as your title.

Rating: 2 out of 10

Title: The Player Agent

Genre: Sports/Biopic

Analysis: Something about this title reads weird. I want to put an apostrophe-s after “Player” so it reads, “The Player’s Agent.” I don’t know what a player agent is supposed to be. Like, he’s good with women and sports agenting? Is he an athlete and an agent? I suppose if that’s the case, it makes sense but no title should create this much confusion.

Rating: 4 out of 10

Title: Better

Genre: Psychological Thriller/Horror

Analysis: Too little info. There are simple one-word titles and then there are words that provide so little insight into the story, they’re pointless. But I have some good news for the writer, Rosario, so that this analysis goes down a little easier. Your script made it into the Maybe/High pile.

Rating: 4 out of 10

Title: Bring Me The Head of Harvey Valentine

Genre: Action/Adventure

Analysis: One of the few titles I’ve received that really goes for it. It wants to make a statement with its title and I like that. It’s one of the more memorable titles I received. My only pushback would be that it’s not that original. I’ve come across that phrase enough that it doesn’t do a lot for me. Even the name is unoriginal. Had the name been something more outlandish, that would’ve helped the title a lot.

Rating: 5.5 out of 10

Title: Almost Airtight

Genre: Horror

Logline: I would avoid using words like “Almost” in your title for anything other than comedy scripts. The word has a flimsy implication and therefore doesn’t line up with horror. Words like “Maybe,” “Almost,” “Basically,” – these are comedy title words.

Rating: 4 out of 10

Title: Do Us Part

Genre: Rom-Com

Analysis. Obviously, we’re playing off the phrase, “Til Death Do Us Part,” but not in a way that’s clear. It took me a coupe of reads to understand it. This feels like one of those situations where the writer is trying to be too clever by half.

Rating: 3 out of 10

Title: Get Woke

Genre: Buddy Comedy

Analysis: Anything that makes fun of a current public ideology is ripe for a comedy title. The trick with comedy titles is that, while they don’t need to make you laugh, they need to imply a world where you can imagine laughing a lot. Which this title does.

Rating: 7 out of 10

Now that we have our 25 titles, let’s rank them. Yes, I know these don’t perfectly reflect my ratings but this is how I ranked them from memory. From worst to best!

25 – The Little Friend

24 – Hexagram

23 – Dark Lands

22 – Way

21 – The Commune

20 – Out of Time

19 – A Violent Noise

18 – Tigers

17 – Better

16 – Goodnight Nobody

15 – The Player Agent

14 – Getaway

13 – Do Us Part

12 – Arkanum

11 – Big Trouble in Breckenridge

10 – Almost Airtight

9 – Bring Me The Head of Harvey Valentine

8 – Get Woke

7 – Dolly

6 – Skin

5 – Lotus

4 – When Tomorrow Starts Without Me

3 – We’re Doing Just Fine

2 – The Good People

1 – Candyflip

Genre: High School/Comedy

Premise: A high school gossip blogger uses his influence to help a nobody win prom queen while subsequently taking down the most popular girl in school.

About: This script broke through two years ago and made the Black List. The writers, Hannah Hafey and Kaitlin Smith, are brand new on the scene.

Writer: Hannah Hafey & Kaitlin Smith

Details: 107 pages

I encountered an interesting scenario the other day.

I’m working with a writer on a script who ran into another writer at a party, who he then told about the script. After listening to the pitch the other writer said, “Well the first thing you should know is that I hate those kinds of movies.” But she still offered some suggestions about the script, including one about the ending, which it turns out, was a good idea.

It got me thinking, who’s the better person to give you notes on a script? Someone who loves that type of movie or someone who hates that type of movie? You’d think it would be someone who loves those movies. They’re more tuned into the genre and what makes it work. Therefore, they know the trappings better. And they’re more familiar with the world, which gives them an advantage in how to critique it.

But the thing about the reader who hates those movies is they have no attachment to the genre and therefore are completely objective. They’re much better at calling out the bullsh#t because they have zero patience for how these movies operate. This creates a scenario whereby, if you can win this person over, you can win anybody over.

They also push you in directions that aren’t usually taken in that genre, since they don’t know the blueprint, which results in more original stories. Then again, the flip side of that argument is that if you’re asking for notes on your horror script from someone who hates horror and their note is, “Horror is so cliche. Focus more on the drama,” you might end up with a horror movie that isn’t scary. Has your script really gotten better in that scenario? Thoughts in the comments!

One thing I do know is that if you can win me over in a genre I don’t like, you have something special. It just happened a few weeks ago so let’s see if it can happen again!

High school senior Ollie St. John is a cross between Perez Hilton and James Charles, a high school blogger who dishes on all his high school’s gossip. While not popular himself, he can make or break anyone in school with a few choice sentences.

One of his ongoing targets is Harper West. Ollie doesn’t hate Harper West so much as he hates the idea of Harper West. She comes from a well-off family. She’s gorgeous. She doesn’t have to do anything but show up to school to be insanely popular. Despite years of attacks on her, though, Harper has survived his onslaught.

Enter Ava LaMonte, the new ugly duckling transfer. Ollie knows he can Rachel Leigh Cook in She’s All That this girl so he makes an alliance with her. He’ll help her become popular with his endless fashion and beauty knowledge along with the power of his blog, as long as once she’s in the ring of popularity, she invites him in.

Everything goes according to plan until Ava gets a true taste of popularity and wants more. More more more! She starts going rogue, not content with being popular. Now she needs to take Harper’s place! To win prom queen! So she screws up Harper’s college interview. Befriends her friends. Befriends her parents. Even steals her boyfriend! Say what!? Yes, Ava has done the impossible. In just a few months, she’s become the most popular girl in school.

Ironically, this forces Harper into a temporary alliance with Ollie, who’s kind of embarrassed about his creation. But do the two have enough power to take down the 10 billion megawatt star that Ava has become? All before prom? It’s not likely. Which means they’ll need to pull out every trick in the book to win.

I’m going to kill the suspense.

This was not one of those disliked genre scripts that won me over.

It started off strong. The first couple of pages (an Ollie voice over where he lays out high school and the power of popularity) contained a wit and an edge that reminded me of the gold standard in this space, “Election.” That’s what you have to be good at to excel in the high school genre. You need to have a bite to your dialogue. And you need to have a little bit of edge to your storytelling.

Ollie:What? Was I not supposed to let the people in on when Jackie Powers let a Golden Retriever lick peanut butter off her snatch?

The reason for that is high school stories work better when you lean into the messiness of them. If you try to play them too sweet, they come of as generic, no different from one of the 50 high school TV shows anyone can watch. With a feature, you have to give them something they don’t get elsewhere (I know these lines are getting more blurred every day but I still think the general rule applies).

But after those first couple of pages, the script backs into the trenches. It never quite goes after the story the way it did in the beginning. Whenever you’re too reserved with a high school script, you’re giving us a story we’ve seen before. Because high school is one of those subjects where it’s hard to say something new about it.

Storytelling is about having something to say. What is it you want to say about people? What is it you want to say about this world? If you’re not asking questions like that when you’re writing one of these movies, you’re probably not getting the most out of your story.

“Popular” had some nuts and bolts screenwriting issues as well. It has a really weird approach to its characters. Ollie is our narrator. So he’s who we meet first. But then the baton is passed to Harper, so we think she’s our protagonist. But then Ollie keeps peeking back in, jostling for position. Then Ava arrives and since she’s the most active of the three, she becomes the de facto protagonist (pro tip: Whoever the most active character in your script is, that should probably be your protagonist).

You might say, “Maybe it’s a multi-protagonist script, Carson. You’re being too dogmatic trying to find a traditional hero.” And, in the writers’ defense, they did something similar to this in Election. And I love that script. But there’s an elegant way to do it and there’s a messy way to do it. Election was so clean in the way it delineated between its protagonists. It separated them into their own clear storylines. Whereas this just throws characters at you willy-nilly, with no rhyme or reason to why they’re being introduced in the order they are, and puts the onus on you to figure it out.

To make matters worse, there wasn’t a lot of good to choose from. We have an evil gossipy blogger, a cutthroat nerd, and a current popular girl. Of the three, Harper was probably the nicest. But she didn’t do a whole lot to make me sympathize with her. Which means you’ve given me three imperfect options, none of whom are sympathetic.

At the risk of piling on, all three of these characters are built on top of a mean goal. Two people are trying to take down a third person. Mean goals can work. It’s just harder to make them work because it’s harder to get on board with people who are trying to do something bad.

BUT!

I didn’t like Booksmart. I didn’t like Mean Girls. I didn’t even like Clueless. So maybe these scripts just aren’t my thing. I’m interested to hear what those of you who like these kinds of movies thought of Popular.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: You have to put the same amount of effort into the rest of your script as you do your first two pages. If I had an In and Out burger for every time I read a script where the first two pages were the sharpest, cleanest, coolest best-written pages ever, only for the rest of the script to read messy, jumpy, ragged and weak, I would be 9 million pounds and have some major artery issues. I mean what do you think is going to happen? I’m not going to notice? I’m going to magically not realize that one page that’s been rewritten 3 times isn’t different from the previous page which was rewritten 7000 times? I know it takes longer, but you need to treat EVERY PAGE like those first couple of pages. If you’re going to rewrite that first page sixty times, make sure you rewrite page 72 sixty times. Make sure you rewrite page 14 sixty times. When I see that drop in quality after the first couple of pages, I know I’m in for a bumpy ride.

Genre: Sci-Fi/Thriller

Premise: When a major accident occurs at America’s first giant particle accelerator, a hazmat team is sent in to measure the damage, only to realize that something about the event feels like deja vu.

About: This is a spec script that sold a few years back to Lionsgate. Screenwriter Justin Rhodes made a name for himself in the early 2010s, selling a number of sci-fi scripts. He was finally rewarded with his first high profile studio job, writing 2019’s Terminator: Dark Fate.

Writer: Justin Rhodes

Details: 119 pages

Today I was going to review that new The Making of Godfather project that Oscar Isaac will star in. But, what do you know, I already reviewed it!

So I went into my stash of screenplays and I found this bad boy which sounded right up my alley. Did you say particle accelerator? Did you say experiment gone wrong? Did you say the same people keep showing up over and over every day after you’ve killed them and you don’t know why?

High concept salacious sci-fi gets me all giddy cause I keep thinking one of these scripts is going to be the next Source Code. Will it be the grammatically questionable, “The Join?”

It’s the near future and the U.S. has built their own giant particle accelerator, just like the Large Hadron Collider, 500 meters underneath the New Mexico desert. But when there’s a giant explosion inside, the government has to send a team to close up the air ventilation system so smoke doesn’t make it up into the air, as it’s suspected to be contaminated.

That hazmat team, led by 31 year old Pete Katrola, stumbles out of the exit, into the desert, with bad news. Everyone down there is dead. An evac team takes them back to headquarters where all of them are asked about what they saw. But something is off about the questioning. The scientists almost seem… bored. Which is odd under the circumstances.

Then, after the last question, the scientists leave the room, gas is poured in, and the entire team, including Peter, dies. WTF?? And if that’s not weird enough, we cut to Peter and his team AGAIN inside the particle accelerator. They do the job again, come outside again, and again are interrogated by scientists. AGAIN they’re gassed.

BUT!

This time they don’t die. The gas has no effect on them. Peter and the team, realizing they’re being gassed, break out of the room and attack the scientists. Peter is able to take 63 year old DOCTOR GEOFFREY MCKISSICK hostage, and sneak out of the building and drive off. Peter wants answers now!

McKissick explains that, seven years ago, there was an explosion inside the particle accelerator and Peter’s team was sent in. They were questioned, only for the next day, the exact same thing to happen and a SECOND team of Peter’s appear at the exit. Same thing the next day and the next. For seven straight years now! Which means they’ve killed Peter’s team hundreds upon hundreds of times.

Peter ditches McKissick to find his wife who he doesn’t realize thinks he died seven years ago. After a lot of convincing, she finally believes it’s him, and the two go on the run together. The government comes chasing after him though because whatever was down in that accelerator was contagious. If Peter is able to make it back into society, he could potentially contaminate and kill everyone on the planet. Duh-duh-duhhhhhhh!

When it comes to this genre, I see the same mistake made over and over again, regardless of whether it’s a beginner screenwriter, an intermediate, or even a professional. In fact, it just happened to one of the biggest most successful writers ever, resulting in the failure of a 200 million dollar movie.

When it comes to science-based science-fiction, the science and the rules need to be impeccably explained. And the execution of the science and rules must be clear as day. Otherwise you’re building your narrative on this ooey-gooey pseudo-science that never makes sense, which means it always feels fake.

Tenet is a case study in this. It wasn’t clear how the stuff from the future was getting here. It wasn’t clear how the backwards objects worked. It wasn’t clear how the backwards world worked. In every scene where those things mattered, we only understood, maybe, 60% of what was going on. That’s what a lack clarity does in science-fiction. If we don’t understand the rules of the game, there’s no way for us to enjoy it.

I’ve found that both beginners and professionals make this mistake but they do so differently. The beginner makes the mistake because they’re sloppy and don’t know how important clarity is in a script like this. The professional (Nolan with Tenet) knows this but he deliberately holds back the information in the spirit of “challenging” the reader. Ironically, both roads lead to the same problem. We’re confused.

The Join has a lot of cool ideas but it falls into this same trap. We don’t understand what’s going on. We get that there was an explosion. We get that the particle accelerator may have opened some doorway to another dimension. We get that that may be the reason new Peter Teams keep showing up (cause they’re from these other dimensions?). But none of it *really* makes sense. The more you think about it, in fact, the less sense it makes.

This is why the original Source Code draft (not the movie you saw – the original spec draft) was such a great script. It explained its rules so well that we were easily able to take part in the story. And Ben Ripley, the writer, told me himself, that he worked tirelessly on making those rules clear because he knew if they weren’t, the screenplay wouldn’t work.

Honestly, I don’t think this is a talent issue. I think it’s an effort issue. Writers don’t want to do the work. Most writers writing these complex science-based scripts stop once the script *makes sense.* That, to them, is a major achievement. But, in theory, that should be your beginning point. Getting your script to make sense is expected. Nobody gives out Oscars for movies “that made the most sense.” You work through all the annoying science-y logical stuff to get to a point where you can actually explore the idea in an entertaining way.

The Join only gives us the bare essentials of what’s going on, leaving us confused as to what the ultimate goal even is. I guess it’s to get Peter back so they can kill him and prevent more contamination. But since I don’t really understand what caused this, what the rules of what caused this are, why his body is changing at the molecular level, why previous versions of him died from the gassing but this recent version is immune to gas, or what any of this has to do with him having a highly transmissible disease… since all of that was vague, I didn’t care what happened.

That’s what so many writers don’t understand. If we feel like you’re not giving us the facts due to laziness, why wouldn’t we also take part in that laziness? If you ain’t gonna try, why should we?

It’s an issue that gets to the heart of what it takes to write a good screenplay. It really does. The collapse of the spec script is in large part due to writers cooking up scripts in three months and thinking they’re genius. Once enough of those scripts got purchased and made, only to become box office disasters, though, Hollywood stopped buying them.

Luckily, there’s a silver lining to all this. If you’re one of these writers who DOES put in the effort and you’ve thought through every single science component of your story so that when characters talk about it, it feels truthful, and when you build plot threads around it, they feel real, then your script is going to stand out. You still have to know the basics of effective storytelling. If you spend two years researching your science but you don’t know what a character arc is, it’s probably not going to matter. But assuming you know how to tell a story, make sure you do your due diligence and become an expert on your subject matter.

Cause we readers know when you’re b.s.’ing us. We know when you and your characters don’t know what you’re talking about. TRUST ME.

I was hoping this was going to be a surprise winner but it’s just too messy.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: When you have a unique concept, you don’t want to use big chunks of your screenplay to explore things that don’t take advantage of that concept. Here, we have a particle collider and some characters who keep appearing every day, no matter how many times you kill them. That’s where your concept is. So when Pete escapes and spends 30+ pages on the run with his wife, we’re nowhere near that unique concept. Your script has become a straight “on the run” movie. It could be about anything. It would be like, in Source Code, if he got out of the train at the midpoint and tried to integrate back into the world. Plot points that don’t take advantage of the the most unique thing about your script should be avoided.