And I tell you the screenwriting secret that got the writer the job.

This past week, I stumbled upon an interview between Star Wars Theory and Stuart Beattie, the original screenwriter of the Obi-Wan movie. Beattie is best known for penning the Michael Mann Tom Cruise collaboration, Collateral. He was also involved in several of the Pirates of the Caribbean movies. Beattie came on to Theory’s popular Youtube channel to discuss his original vision for an Obi-Wan movie before the feature was canceled (and later resuscitated to become a TV show).

Let me take you back to a time when The Force Awakens came out and made 2 billion dollars. When Rogue One, which was just some random Star Wars special effects’ dude’s idea, made another billion dollars. Anything that Star Wars touched turned into an Erewhon Hailey Bieber smoothie – pricey but oh so sugary good. Things were so optimistic inside the company at the time, they were knee-deep into development on a Jabba The Hutt movie. Guillermo Del Toro even wrote the thing! As Jabba would say: “Tu babba gu janna.”

So of course – OF COURSE – back in 2017 they were going to make an Obi-Wan movie. Obi-Wan was the most popular thing to come out of the prequels and fans wanted more. But then the one-two punch of Last Jedi and Solo hit and, in the time it takes for Joker 2 to move from theaters to streaming, hope crumbled. Unicorns turned into rancors.

But then, a lifeline! The Mandalorian premiered on Disney Plus and everything was delicious once more. Baby Yoda was the juiciest lifeline in the Mouse House and we all got to drink from his backwards yodeling cup.

Star Wars had always been thought of as a big-screen franchise but now the company could see all these new avenues appearing on the small screen. Which meant that Obi-Wan was CPR’d back to life. But, with new mediums come new writers. So, Beattie was cast aside and most of what he wrote was tossed in the Death Star trash compactor. Instead, we got Leia. As a baby. And a chase scene that brought back memories of the Star Wars Christmas Special.

Now, due to this interview with Beattie, we finally know what that Obi-Wan movie was going to look like. Presumably, it would’ve been light years better than the uneven low-budget TV show that came and went faster than a pod race practice lap.

To make a long story short, the bulk of Beattie’s movie focuses on two things. One, Obi-Wan has lost his connection to the Force and must find it again. And two, an excursion to a transport station – a sort of “airport” in the middle of the galaxy – where aliens from all walks of life switch spaceships before they head off to their final destination. Obi-Wan meets some Force-Adjacent aliens there and they help him reconnect with the Force so he can take on Vader in the third act, who is getting close to finding his young son, Luke Skywalker.

Now, I don’t know about you. But that doesn’t sound very exciting to me. I mean, props to Beattie for coming up with a place that nobody else in Star Wars has come up with before in this transport station. But it’s not exactly… The Death Star. It’s a place of annoyance. Frustration. Waiting. Are those words I associate with Star Wars? Well, these days I guess they are. But you know what I mean. Annoyance isn’t able to compete with… A TERRIFYING SPACE STATION THAT CAN DESTROY ENTIRE PLANETS! On the fear factor hierarchy that’s a bit above, “Oops, I missed my space flight. I’ll have to rebook it for the 9pm.”

Why am I bringing all this up?

Because when you become a professional screenwriter, your primary job will be pitching your take on stories that other people own. You may not ever get a chance to pitch a Star Wars movie. But you could have to pitch a Voltron movie, a Gremlins reboot, an It Ends with Us sequel that no longer has the male lead since the two main stars don’t get along anymore, a more accessible version of the trippy “Wind-Up Bird Chronicle” by literary genius, Haruki Murakami.

The better you are at finding fresh exciting story angles, the more jobs you’ll get.

But, every once in a while, you’ll be tasked with an impossible pitch – something that doesn’t have any viable stories left. Let’s be real here. NOTHING HAPPENED during Obi-Wan’s time on Tatooine between Episodes 3 and 4. He didn’t go on any more adventures. And even if he did, how could those adventures possibly be as interesting as what happened in A New Hope, or what happened back in the prequels?

A movie should always represent the most important moment in the protagonist’s life. Even if you could convince yourself that Obi-Wan still had adventures during his time on Tatooine, what are we talking here? The 7th most interesting adventure he’s been on? The 8th? Heck, I’d even watch a movie where Obi-Wan and Anakin got trapped in that nest of Gundarks we heard about in Episode 2 over missing a series of flights on a transport station.

But then what do you do as a screenwriter? Do you just not show up to the pitch meeting? Do you call Kathleen Kennedy and say, “Hey Kathleen, I’ve loved Star Wars my whole life and it’s been a dream of mine to write a Star Wars movie but, you know what? There aren’t any Obi-Wan stories left to tell here. My advice is you scrap the project.”

Of course not. You give it the old college try.

And Beattie did the number one thing I believe writers should do in a pitch meeting like this. Don’t focus on the plot. I mean, DO focus on the plot. But not as the heart of the pitch. Instead: Figure out the CHARACTER ANGLE and pitch that first! Because, beyond this world where you’re trying to get a movie made, there’s a more immediate goal, which is to WIN THE WRITING JOB. I have no doubt that Beattie won the job because he came in there and pitched CHARACTER over STORY.

He said: “What if Obi-Wan has lost his connection to the Force? And the movie is about getting it back.”

NO QUESTION IN MY MIND that that’s what won him the job. Cause everyone else who came in probably pitched some iteration of Obi-Wan and Vader having some secret battle. They probably pitched many expensive Star Wars set-pieces. But that stuff gets boring in a pitch. You want to connect with the person in front of you on an emotional level. If you can do that, they’ll then see all these other things (fight with Vader, cool set pieces) through that lens. And that’s a way more powerful lens.

Cause the truth is, this movie wouldn’t have been any better than the TV show. You cannot build a story out of a character’s 8th most important adventure in their life. You just can’t. So it’s a losing proposition before you even get started.

BUT!

As far as winning the job? That can certainly be achieved with this character-driven approach.

By the way, you can prepare yourself for this future of pitching production companies by practicing pitching your own properties right now. Get good at that. Tell people about your ideas and, if you’re not getting the responses you want, make changes to your pitch and try other things until you can see them responding positively to you. Move things around. Focus more on character. Get rid of the parts that people looked bored during.

But for crying out loud – pick ideas that highlight the most important adventure that your character has ever been on. Otherwise, it’s always going to feel like we’re watching something second-rate.

If you’re looking for notes on your latest screenplay or pilot, I will give the first THREE writers who contact me 40% off my full rate. So that would be $299 for a consultation. I will take another $50 Halloween discount off if it’s a horror script! E-mail me at carsonreeves1@gmail.com right now to sign up!

You know what they say. Mole people, mole problems.

Genre: Horror-Thriller

Premise: When his homeless brother is violently slaughtered by a mysterious killer, a plumber looks into his murder and learns that it’s connected to a group of people who live deep underground.

About: Today we have a writer with very few credits. But the credits he does have are of high quality. He has written five episodes of titan TV series, Succession. This script got him onto the bottom end of the Black List.

Writer: Nathan Elston

Details: 111 pages

Hey!

It’s Halloween Month.

You know what that means, right?

Horror scripts and CANDY.

I went to Salt & Straw today. For those who don’t know, this is a bougie ice cream spot here in LA. They let you sample all of the flavors. So I asked them for their best Halloween flavor. They gave me something called The Great Candycopia.

There have only been seven times in my experience here on earth where I transcended this plane and existed inside another higher one – a place so heavenly, the air tasted like In and Out double-doubles. The Great Candycopia brought me there for an eighth time. And I will always remember that experience for what it taught me: The meaning of life.

Now that that’s taken care of, it’s time for me to bring you to another plane – that being a review of Molepeoplemoleproblems.

28 year old Jack lives in New York. He’s barely making ends meet as an assistant plumber. We see Jack look the other way when his boss extorts a client by price-gouging her at the end of the job. His boss reminds him afterwards that if he even thinks about complaining, he’s got a hundred guys ready to take his place in a heartbeat.

That night when Jack is home to take care of his dementia-ridden father, he gets a call from NYPD who tells him that his brother, Patrick, is dead. Not only dead. But his eyes have been chopped out! What’s up with that!

Jack goes downtown to take a look. His brother was homeless and the two had a difficult relationship to say the least. But he still wants to know what happened so he heads off to find some friends of Patrick’s. Soon he’s following a guy named Edwin down an operational subway tunnel. The two go down several holes until they’re in some deep deep DEEP unused NY tunnel and Edwin shows Jack Patrick’s bedroom.

No sooner does that happen than Edwin is attacked by some crazy subway-dwelling psychopaths who rip his eyes out. They then chase Jack through the depths of these tunnels and Jack stumbles upon some enclosed room where a woman is being held hostage. He tells her he’ll come back for her and manages to escape back to the surface.

But when he tells Edwin’s friend, Jimmy – who’s strangely neutral about his buddy’s demise – about the ordeal, Jimmy says to forget the girl. In fact, get the heck out of New York. These mole people are serious dudes and now that Jack knows where they live, they’re going to come after him. Even up here! Torn by the threat and his promise to the woman, Jack must decide whether he’s going to see this to the end or not.

Here’s the reality about missing people in fiction.

You want to lean into the missing people main traits that create more investment from the reader. Those traits are: WOMEN or CHILDREN.

Most readers (and viewers) aren’t going to care if a man has gone missing or murdered.

There are sub-traits you can utilize that result in more investment. However, there are sub-traits you can utilize that result in less investment as well.

One negative sub-trait, for example, would be homelessness. The average viewer does not care about homeless people. The media pretends they do. But they don’t.

This script is built around a murdered MAN who was HOMELESS.

That’s a negative main trait and a negative sub-trait when it comes to investment. So, already, you’re starting below ground level, no pun intended.

This isn’t a game, guys. The creative choices you make when building your story have benefits and they have consequences. The more weak creative choices you make, the less invested the reader will be. The more strong creative choices you make, the more invested they’ll be.

We saw this at the beginning of the week with Joker 2. A few key creative choices that weren’t good (a so-so love story, a court case with unclear stakes, several subplots that should’ve been cut) doomed the movie.

But when you’re talking about investigative storylines that are built around murder or missing persons, the data is clear. You want women or children to be the ones murdered or missing. And the more positive sub-traits you can pile onto those victims, the better.

To the writer’s credit, after the brother’s body is discovered, he introduces an imprisoned female character. Which happens fairly early in the script – 38 pages in. This makes us much more likely to care. However, we know nothing about this woman character. She’s just a random person. So she has no sub-traits that are going to increase our investment.

Luckily, the script also has this mystery at its center. Who are these mole people and why do they want to rip peoples’ eyes out and murder them? That did make me kind of curious, which helped keep those pages turning.

But, at the same time, I never fully cared about what was going on and part of that was because I’ve been reading scripts about scary people living in the abandoned New York subway system for over a decade. Not a ton of them. But probably between 7-10 scripts. And every one struggles to feel big enough. They all feel like “almost movies.” The stakes never seem high enough. The threats never seem scary enough. The plots never have satisfying enough reveals.

I’ve thought a lot about why that is and I’m still not sure. But part of it is that these people are underground and so, as long as you stay above ground… YOU’RE FINE! Even when one of these guys come up to Jack’s apartment to attack him, it doesn’t feel scary because it’s just a normal guy attacking him. There’s nothing special about him. I don’t know. I wasn’t scared for Jack.

It’s not like, say, It Follows, where you genuinely felt overmatched. Everywhere you went, that evil following entity could be there. I was scared for those people.

By the way, that leads to another horror trope that helps in a movie like this – making the protagonist female. If she’s female, we feel more fear for her. Had that attacker broken into the apartment of Hero Jill as opposed to Hero Jack, I would’ve definitely been more on the edge of my seat.

But Jack?? Jack is 28. He’s strong. Why would I feel fear for this guy? This is why most horror protagonists are female.

To the writer’s credit, the script makes a bold choice at the end. I didn’t see it coming. But it couldn’t erase the issues I detailed above. This script needed MORE. It’s another FINE script. But to be a script that affects people, it needed to be a lot bigger.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: I think a lot of this could’ve been solved by making the initial missing person Jack’s girlfriend (or ex-girlfriend) who is an addict. She went using again. That’s why she was hanging out with the wrong people. That’s how she ended up getting taken to these underground tunnels. Now you’ve got an emotional connection between the protagonist and the missing girl. I still don’t know if we care enough about mole people but it certainly would’ve added more investment to the story.

What I learned 2: If you want to improve the chances of an idea like this selling by as much as 10-fold, make it supernatural. If the things underground were supernatural, this could be a 3000 theater wide release. Keeping it realistic makes it feel too tame. It just never shook the Richter scale.

YES! I’m finally reviewing it!

Genre: Sci-Fi

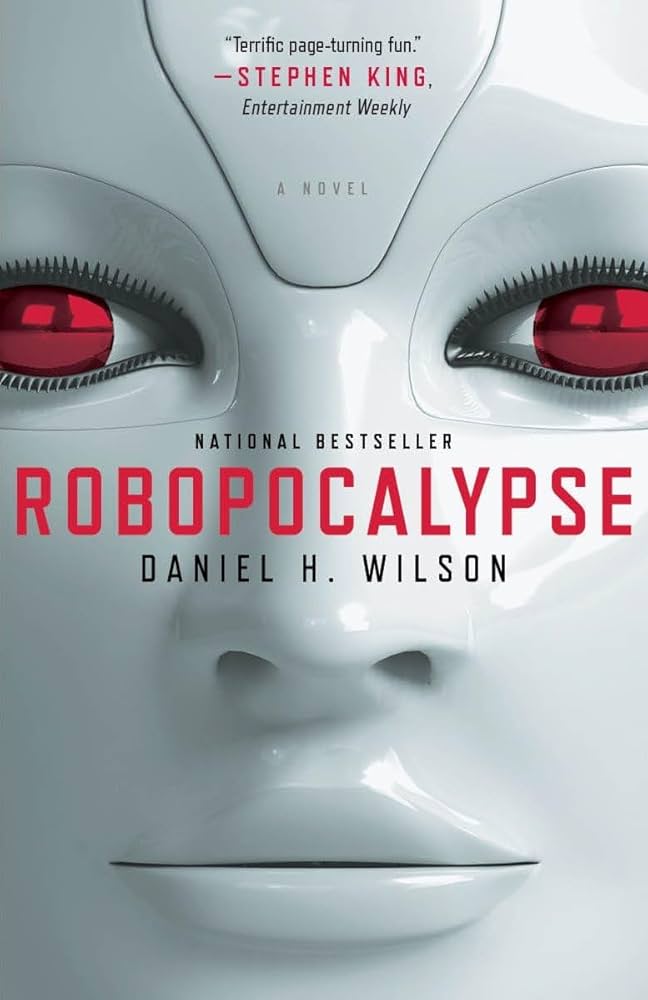

Premise: After the humans win the war against the robots, we get a highlight reel of the major moments that led to both the rise and fall of the machines.

About: Robopocalypse is one of the most famous properties ever purchased by Hollywood due to the fact that Steven Spielberg was announced as the director. The book was optioned in 2011. Drew Goddard was hired to adapt. Chris Hemsworth was hired as the male lead with Anne Hathaway in the main female role. The 200 million dollar film was scheduled to be released in 2012 by Disney. But Spielberg delayed it and then, a year later, left the project. The book’s writer, Daniel Wilson, to this day is hoping it makes it back onto some studio’s radar.

Writer: Daniel Wilson

Details: 350 pages

As I look back at Spielberg’s output over the last decade, I keep thinking of how it could’ve changed for the positive if he had directed Robopocalypse. The name alone screamed “GIANT SUMMER MOVIE” and felt like a perfect strike for the best mainstream director of our time.

So when he suddenly abandoned the sure-fire hit to send audiences into 2 hours of cryo sleep with Lincoln, I was disappointed. The funny thing is, I had no clue what the story for Robopocalypse was other than there was going to be a robot apocalypse. But that was the genius of it! It’s one of the great titles in title history, like “Monster-In-Law.” You knew EXACTLY what the movie was about just by hearing the title! It would’ve made hundreds of millions of dollars. Heck, it might STILL make hundreds of millions of dollars.

So I decided to finally read the book and do some detective work (along with some serious speculation) to discover why Spielberg may have left the project. And you know what? I think I figured it out. Before I share that with you, here’s a quick breakdown of the book.

We start out deep in the northern part of Alaska as soldiers dig out some sophisticated computer equipment from a giant hole in the ground. We’re told by soldier Cormac Wallace that the “New War” is over. The humans have defeated the robots. They are recovering the central computer, Archos, that controlled the attack. As a result, they will have all the major recorded events that led up to the war.

The book then is a “curation” of the most important events Cormac found in the hard drive. Everything from official interviews to events that security cameras caught on city streets are all on file. This allows the author, Daniel Wilson, to write a bunch of short stories. It is both the best thing and the worst thing about the book.

These stories include the first robot attack, which takes place in a convenience store where a robot bludgeons an employee to death. Another story follows a group of workers at a factory who play a prank on their weird older boss, kidnapping his love robot and bringing it to work, where it proceeds to attack the older man, biting his face off. We see the night in the city when all the cars – which are all computer controlled now – just start riding up on sidewalks, mowing down as many humans as possible.

My favorite story was when one of the main characters, a congresswoman, is driving her family to her father’s country house to escape the beginning of the war when she gets a call from her father to head to the Indianapolis Speedway instead. She then sees a pickup truck shooting towards her from behind and then it pulls up to the side of her momentarily and we see this woman inside, crying hysterically, banging on the windows for help. The car then shoots forward, steers into the oncoming lane, and plows into another car, each blowing up.

Our rattled mom then does a U-turn to head back to the new destination but meets a roadblock of another crash up ahead. There’s a man from one of the cars lying on the side of the road so she hurries out to see if he’s still alive. He’s dead. And his phone is in his hand. She hears a message from his wife. It says that she needs him to turn around and meet her at the Indianapolis Speedway.

Eventually, the book evolves into a semi-narrative (I say “semi” cause it’s still, essentially, a series of short stories) that follows the resistance and its eventual discovery of Archos’s location. The main regiment that Cormac is a member of teams up with some Native American soldiers and they head to Alaska, where they battle terrain that has been carefully prepped with robot defenses. A lot of people die but, as we already know, the humans win.

Official Concept Art

Official Concept Art

There’s an obvious freedom that comes from not being tethered to a narrative. You can write any short story you want. This allows you to only write the best of the best stories to come out of the war. The problem is, when you don’t have a narrative that pulls it all together, when you don’t have a main character who is guiding you through it all, the reader starts to dissociate from the story. That’s because every time we, the reader, start a new chapter, we’re starting over.

If I had to guess, I’d say that’s the reason the movie didn’t get made.

The book gives you the concept but it doesn’t give you the narrative. As a result, you can go in any direction you want. You can tell the story from anybody’s point of view. While that seems tempting, you are then moving away from the book since you’re not including all of the short stories. What are you really adapting, then?

I bet that what happened was Drew Goddard did that first draft and it sucked because he had too much choice. He could do anything he wanted, which blinded him from finding the best angle. That draft was sent to Spielberg. He probably realized it was the wrong take. And Spielberg knows that good scripts take time. He ultimately decided not to invest that time. So the project was dropped.

Another problem is that the book starts with the war being over and the humans winning. I understand that they did this with the World War Z book as well but I think it’s a terrible way to go into a story. You have zapped any and all suspense the second you tell us who won the war. Why are we even reading then? It’s an odd storytelling choice that I’ll never understand.

And we saw that, in the script development of World War Z, after trying to utilize the original structure through several writers, they realized it was a stupid idea and decided to tell the story in chronological order instead. Which is what you need to do here. I don’t know if Goddard tried to do that on his first pass or not. But if he didn’t, there’s no doubt that’s the reason the draft sucked.

Just like any short story collection, the book works when the short story is good and doesn’t work when the short story is bad. Luckily, there are a lot more good stories than bad here.

There’s a terrifying plane scene where the onboard computers link two planes up to collide and the pilots have to desperately figure out a way to avoid it. There’s a horror chapter where a little girl’s toy bot becomes evil. There’s a story out in Afghanistan where an American and Afghani soldier must team up to take down a determined psycho robot. Wilson has a good eye for dramatically entertaining scenarios.

The only thing that annoyed me was that Wilson would occasionally cheat. For example, he starts out every chapter saying something like: “This event was recorded by a series of public cameras and the sound was recorded by numerous nearby cell phones.” He would then write the story like this: “John had a lump in his throat the size of the Grand Canyon. He was never good with pressure but now he didn’t have a choice.” How is it that public cameras and recording cellphones know that John had a lump in his throat and was really nervous? That makes no sense.

It’s not a huge thing but if you’re going to create these rules to your story – where you’re pretending that all of this was available due to public recordings – you can’t change those rules in order to write descriptive prose. You have to treat it like it’s just the facts. Unless you want to break the suspension of disbelief.

But look. They should still make this movie! With the fast rise of AI, the subject matter is more relevant than ever. All you need is to get a good director and a good writer to read the book then sit down for an 8-hour brainstorming session where you hash out what the best story angle is. There are a dozen angles that could work. Then you go write the thing. I could have a draft for you in a month if you want.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: My approach to adapting something like this would be to write down all of the scenes in the book that you could imagine would make great movie moments, the kind of images or scenarios that you would see in a trailer. For example, that scene of the woman trapped in her truck banging on the windows crying to get out as it passes our protagonist’s car – that’s a trailer moment right there. It totally sells the movie. Come up with as many of those as possible and then see if there’s a version of the story where you can include them all. If you can’t find one, then find one that includes MOST of them. If you still can’t find one, find the idea that incorporates as many of them as possible. Cause those moments are your film-sellers. So that’s what you want to build your story around.

Joker 2 has been getting beaten up by the press all week. But is it actually the best movie of the year?

Genre: Superhero/Drama/Musical

Premise: As Arthur Dent, aka The Joker, awaits trial, he meets a woman in his prison music class who may be just as crazy as he is.

About: Joker: Folie a Deux hit theaters this week and managed to make just 40 million dollars. For comparison, the first Joker made 96 million dollars on its opening weekend. It’s a very concerning number not only for this movie, but for Hollywood in general. Joker was the freshest take on a superhero movie in a decade. For audiences to cool on that take so quickly leaves very few avenues for a still-superhero-dependent studio system going forward.

Writer: Scott Silver and Todd Phillips

Details: 2 hours 18 minutes

Arthur Fleck currently resides in Arkham Prison (or the insane asylum wing of the prison?), where he’s awaiting trial for the five murders he committed in the first film. Arthur lives a fairly mundane existence in lock-up but as least he’s a celebrity. People are always asking him to tell a joke. It helps that they made a TV movie about his murders and it became, unlike this film, a big hit.

While Arthur awaits his trial, the head guard, who’s a friend of Arthur’s, signs him up for a prison music class, and that’s where he meets Harley Quinn, who’s a big fan of Arthur’s. The two fall for each other immediately and when they meet in the class a few days later, Harley covertly sets a fire in the room so they can escape and hang out alone for a while.

Meanwhile, Arthur’s lawyer keeps reminding him how important the trial is, telling him that he must disavow his Joker personality. If he can convince the judge that that version of himself is a lie, is a thing that takes over his body, then he will not be convicted for murder. Arthur acts like he understands but with Arthur, you never know. At no point are all the lights on in Arthur’s attic.

When the trial finally starts, it’s a circus. Everyone wants to be a part of it. Harley, who has since checked herself out of the asylum, is Arthur’s biggest fan. She’s there every single day. But when she sees Arhtur’s lawyer holding him back, she implores him to ditch her. Arthur does and, the next day, shows up to represent himself… as the Joker. What could possibly go wrong?

People are going to tell you this movie is terrible. It isn’t.

Joker 2 is too unique of an experience to be terrible.

When you make a hit movie inside a major franchise, what does every sequel do? They go BIGGER. Right? Bigger set pieces. Bigger effects. Bigger freaking story! And if I’m being completely honest, I would’ve liked to see that. I would’ve loved to see Todd Phillips’ version of Batman. And it didn’t have to be some big story with heists or anything like that. But some conflict with Batman? I would’ve been in.

Phillips eschewed that and, at least from my untrained filmmaking eye, kept things small like the first. Who does that in this day and age? Nobody! Everybody takes the bait. Go bigger, harder, faster! Phillips understands that in the history of sequels going bigger has worked like three times. People liked the first film cause it was simple. So why not keep the second one simple?

Of course, none of that matters if the script doesn’t work.

So, did it?

As I sat there watching Joker 2, I asked that question a lot. I loved the first 30 minutes. Normally, when a script is a slow burn, it’s fast boredom. But this wasn’t that. Getting to know Arthur’s life inside the prison was sad yet unexpectedly sweet. The guards aren’t mean to him. They’re friendly and often joke around with Arthur.

Things lift up when Arthur meets Harley. You can see that this changes Arthur. It’s his first time experiencing real love and he (and we) can’t wait to see them together.

But as the movie went on, I found myself getting bored. I asked myself, “What’s powering the narrative here?” By ‘powering the narrative’ I mean, what’s making us want to keep watching? If I was watching this at home, what are the things that are going to prevent me from turning the movie off and watching Love Island instead?

There were two arguments to be made.

Number 1 was the conclusion of the trial. Theoretically, we wanted to see if Arthur won or lost the trial.

Number 2 was, would he and Harley end up together?

From a screenwriting perspective, these are both strong story engines. They *should* be able to power a story if done well.

Unfortunately, neither worked. Each had their moments. But neither engine could sustain itself. They would constantly peter out, requiring a jump.

With the trial, I think the thing that kept it from working was the stakes. The script never made it clear what would happen if Arthur won. We knew what happened if he lost. He remained in prison. But if he won… well, they never mentioned anything about it if he won. And that’s because they knew that if they told the audience the truth – that he heads to the insane asylum – that it was really no different than if he lost.

So what they did was they never mentioned it HOPING that we would think, hmmm, maybe if Arthur wins, he goes free!

We screenwriters think we’re so slick. That we can dance around these holes. But the truth is we can’t. If the audience doesn’t know what the exact value of obtaining the goal is, they’re going to feel a vagueness while they watch the film. They won’t know why something feels off. They’ll just know they’re not as invested.

But Phillips and Silver were smart. They added a second engine just in case the first one didn’t work. I’ve told writers to do this before. Two engines is better than one. Heck, on an airplane, it’s the difference between landing and crashing into a mountain should one engine flame out.

The second engine is this love story. But I’m sad to report, that didn’t work either. I enjoyed their meet cute scene. I enjoyed a couple of their dance numbers (the tap dancing one was my favorite – the one upbeat number in the film). But the problem is… there was no conflict between them. They both instantly liked each other. So the sum of their interactions was never interesting.

I suppose you can make the Titanic argument here – that the entertainment value of their relationship was not determined by the conflict between them, but rather by the conflict surrounding them. And, yeah, we genuinely don’t know if they’ll end up together. So that’s a reason to keep watching.

But I didn’t care. Something about them wasn’t interesting enough for me to care whether they got together or not.

That left me with little reason to watch.

But there was a third reason the story didn’t work. And it’s something we don’t talk about a lot on the site. It’s what I call, “Script Muck.” Script Muck is half a scene here, a stale subplot there, staying in one section of the script too long there. It is the accumulation of all the things you could’ve cut but didn’t. When you cut those things, the script moves faster. Less boring parts = stronger audience attention.

I’ll give you a prime example of some script muck that should’ve been cut. When we finally get to the courtroom section (over halfway through the film), Arthur starts the case with his lawyer. We get 2-3 long scenes in the courtroom with that lawyer before Arthur finally says, “I’m done with this! I want to represent myself!” And he changes from Arthur into The Joker, which injects the script with some much needed energy.

Why not start the courtroom stuff with Arthur already representing himself? The courtroom scenes were so slow before that. They were script muck. And I know the answer Phillips would give you. He would say that it’s a much more dramatic reveal if we’ve been in court for a while. But dude, it’s not necessary. You could’ve sliced off 10-15 minutes there alone.

I first became worried about this movie when it got a 7 minute standing ovation at Cannes. Not because 7 minutes was less minutes than other standing ovations at the festival. But because the French gave an ovation to it in the first place! If the French like a film, it’s probably terrible.

But then I got worried in the lead-up to the release when I saw that NOBODY was doing press for the film! A major studio production sequel to a big hit and nobody’s out there promoting it?!? That’s straight-up weird. Even worse, the one interview Phillips did, the only soundbite that came out of it was, “I’m done with this franchise.” That doesn’t exactly make me want to run out to the theater. Sheesh.

I guess people were right when they said nobody asked for this sequel. But I still think that if they had made a good movie, people would’ve come out in droves. Or not. I guess we’ll never know!

[ ] What the hell did I just watch?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the price of admission

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: (MAJOR SPOILERS) I saw that this movie got a D CinemaScore. Which is REALLY BAD. But it doesn’t always mean that the movie itself was bad. It means that something happened in the movie that the audience hated. No doubt they were responding to Arthur being killed at the end. This same thing happened with Uncut Gems, when Adam Sandler was killed in the end. That got a D CinemaScore as well, and that movie is a masterpiece. But the lesson here is that the large majority of audiences don’t like when you kill your main character off in the end. You get “cool” points from cinephiles and elder statesman critics and industry folks who love when writers have the balls to say “F Hollywood.” But if you want to write a movie that people actually enjoy, don’t kill your protagonist off at the end.

Title: ”Based on a True Story”

Genre: Comedy Feature

Logline: A struggling screenwriter recruits his writer friends to help him turn his fictional heist script into a True Story in the hopes it’ll make it more marketable.

Scene Setup: Our protagonist, Andrew, is trying to convince his writer friends to help him act out the events of his screenplay so he can claim it’s a true story, thereby making it much more marketable. He wants to use the money to save the bar he works at (and lives in).

For starters, let’s give it up to Dan Martin. Not just for winning. But for winning with a COMEDY ENTRY. How often does that happen here on the site? This guy’s breaking all the rules! So, let’s take a look at the scene in full then I can tell you why I chose it for the competition and why, I believe, it won.

This is a more clever setup than I originally gave it credit for. The main reason I picked it was the combination of the funny dialogue and the relevant-to-screenwriting subject matter. But the concept’s fun too. You have a movie idea. But you know selling it will be much easier if it’s based on a true story. So you then create the true story to base the screenplay on. That’s funny!

As for the scene itself, there are several things to celebrate. Let’s start with the structure because it isn’t apparent at first glance. When you first read this scene, you’re focused on the funny interaction. But, actually, the interaction has a purpose. Andrew’s GOAL is to convince his friends to help him steal this art. Once you have a goal, you have structure, due to the pursuit of an objective that requires a resolution. Either he’s going to convince them or not convince them. We keep reading to find out which one.

A goal also gives us our three-act structure within the scene. The setup – Introduce his plan. The conflict – pushback from the others about the plan, forcing Andrew to work harder to convince them. The resolution – They agree to help.

Contrast this against a scene where friends at a bar are just debating whether true story movies are real or not. We would’ve gotten some funny lines, just like this scene. But after a few pages, the reader would’ve started to get frustrated due to the lack of purpose in the scene.

This is a big difference between real life and storytelling. In real life, it’s fine to go to a bar and debate crap for 2 hours. Heck, I recently had an hour-long debate with a friend about whether Da Bears were any good this year. That’s great FOR REAL LIFE. But if you were to put that debate in a script, the reader would literally hate you for the rest of your life and beyond. There’s no structure to that. Which is where scene-writing comes in. You need to have that PURPOSE within the scene.

Moving on to the characters.

Often, when I read a script, I forget who’s who because the writer hasn’t done a good enough job differentiating the characters. A great place where you can differentiate characters is in their dialogue, which Dan does a nice job of here.

For starters, Dan establishes Andrew as the big talker. So whenever I see a lot of talking, I immediately know it’s Andrew. On the flip side of that, Bob barely says anything. Most of his responses are one line. Then you have Doug, who’s established as the guy who pushes back the most (“Don’t you f&cking dare!” “You’re going to hell.”). And I always remembered Julie because she’s the lone female in the group.

One of the more valuable skills a screenwriter can possess is the ability to write dialogue so specific to a character that we don’t need to look at the character’s name to know it’s them who’s talking. So, if you can pull that off, you are well ahead of the competition.

Another thing this scene does well is highlight something that people think but don’t often say. Larry David built his entire brand on this comedy concept. ‘Based on a true story’ is a bullsh%t notion. People will change dozens of things about the real story if it means improving the script. So to have a scene where characters humorously poke fun at this is a fun idea all by itself.

Of course, you still have to execute it. Aka you actually have to be a funny writer, which Dan is. My favorite part, by far, was when Andrew started bringing up Braveheart and Doug started having a meltdown. It’s funny because Braveheart is a sacred film to many. And, in comedy, you want to exaggerate these humorous anecdotes to get the biggest laughs out of them.

In other words, Doug doesn’t respond to Andrew’s first Braveheart dig with a casual, “Come on, Andrew, you know that’s not true.” You’re not going to get a laugh out of that. You have to go with something more extreme, such as, “Don’t you f*cking dare.” And when Andrew keeps going, Doug delivers my favorite line of the scene: “Blasphemous! That script is canon!”

It’s funny because, a) there was no talk of “canon” in the 90s. And b) there’s no such thing as real-life canon. The second that line was delivered, I knew the scene was going into the showdown.

Another thing I liked about the dialogue was the balance between structure and playfulness. You need both when you’re writing a comedy. But too much of either can kill the scene. For example, if you add too much structure, it can restrain the scene. Let’s say Andrew started with, “Okay, we only have 60 seconds before [our boss] comes back. We have to figure this out now.” Sure, you’re adding more structure to the scene via a time constraint. But you’re also not letting the dialogue breathe.

One of the fun things about this scene is that the dialogue has that element of real life where people talk a little too much. Did Andrew really need to add the point about how Mel Gibson tried to get a “true story” label for Passion of the Christ? That could be cut and the scene wouldn’t miss anything. But it comes out of the flow of the conversation so it works.

With that said, if the group decided to run down Mel Gibson’s best movies and Dan tries to get a bunch of jokes out of that, the reader likely would’ve said, “That’s too much.” In other words, there is a limit to “dialogue flow,” just like there’s a limit to structure. Good screenwriters understand that balance well.

I talk about this stuff and a lot of other dialogue intricacies in my dialogue book, “The Best Dialogue Book Ever Written.” Make sure to grab a copy if you haven’t already.

I can’t leave without pointing out the value of “writer comfort.” Dan feels very comfortable in this setting. Whereas maybe another writer doesn’t feel as comfortable writing ensemble dialogue. They feel more comfortable writing an action set piece on a pirate ship. Find your comfort zone and write the best possible thing you can in that space. I’m all for challenging yourself and trying new things. But your best writing is usually going to take place in the genres you feel comfortable in.

Good job Dan! And if you have the entire script, I’m more than happy to review it on the site. In fact, I’m willing to review any script from the top three vote earners since all three of those entries finished so close together. Just send the script my way! :)