Genre: Sci-Fi/Horror/Drama

Premise: Amid a rash of cattle mutilations in the ‘80s, a rural veterinarian holds an alien captive with the desperate hope that its miraculous healing biology can save his terminally ill wife.

About: This is the runner-up in the First Page Showdown. If you’re wondering why we’re reviewing the runner-up and not the winner, it’s a long complicated story but the gist of it is, the winner hadn’t finished his script yet and so we’re waiting on that before we can review it. Actually, that wasn’t long or complicated. It was pretty straightforward. Okay, let’s get to the review. Oh! And remember that we have Halloween Logline Showdown coming up next week. Get those loglines in!

Writer: Mark James

Details: 94 pages

Here’s the first page if you want to reacquaint yourself with it.

Lucky us.

We got a horror script just a week before Halloween Showdown! Sometimes the script gods shine down on us.

BUT!

The script still needs to be good. And the whole reason I picked this first page to compete was because it felt like a different kind of alien movie.

Let’s see if my instincts were right.

The year is 1985. We’re in Nebraska. We meet 30 year-old Dr. Lee Crutchfield as he is elbow deep inside of a dead cow’s rectum. Lee is a vet and although he’s seen a lot, this is not a normal Tuesday night for him. This is actually quite rare.

Word on the street is that cows from all over the local area have been getting mutilated. But Lee’s not buying it. He thinks an animal did this and is vindicated when a rabid badger pops up and he shoots it dead. He tells the rancher he has nothing to worry about, grabs the dead badger and heads back to the clinic to do tests.

Before he does that, though, he heads over to the hospital to see his late 20-s wife, Blair (who he calls “Mother Bear”), who has some sort of weird disease that causes dementia. Her situation is getting worse by the day but Lee is not giving up.

Back at the clinic, Lee spots the dead badger levitating, only to realize it’s being shuttled away by a cloaked 8 foot alien. Lee is able to neutralize the alien with a cattle prod and chain it up. Although the alien is coy at first, it eventually comes clean regarding having the magical ability to cure.

While all this is happening, an Omaha FBI agent named Annabelle Sable shows up who seems to have some knowledge about these aliens. She tells Lee that these off-worlders are not to be trusted! Everything they say is a lie. But all Lee hears is “healing.” So when his wife goes into a coma, Lee decides he’s using the alien cure to save her. But at what cost? And what happens if it doesn’t work?

I had a lot of thoughts swimming through my brain when I finished this script. I knew I could take the review in a familiar direction.

But since this all started with a First Page contest, the question that seemed the most relevant was, “Did I get the script I expected to get from the first page?”

The answer is no.

That’s not a bad thing. It’s just that when I read that first page, I imagined this thoughtful interesting take on aliens where the writer approached things from an angle that we hadn’t seen before. Cause this is a movie about aliens. And most movies about aliens start out with an on-the-nose scene that screams from the mountaintops that the movie is about aliens (i.e. a spaceship in the sky).

By approaching it via a dead cow’s rectum, you told us that this was going to be a different kind of journey (not unlike how we started in Adam Sandler’s rectum in Uncut Gems and got a totally different movie).

And while I suppose you could argue the script does turn out to be different, it ended up feeling too familiar when it was all said and done.

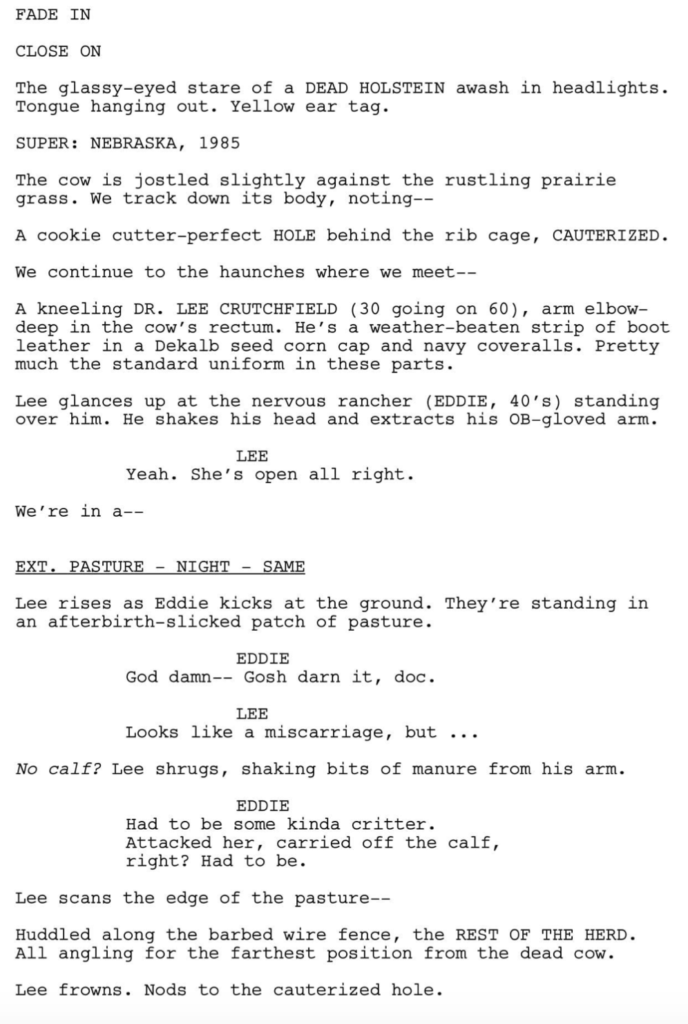

To the writer’s credit, he takes creative risks, the most visual being the alien’s dialogue. This is how all the alien dialogue looks:

What I liked about this choice was that an alien is going to look weird. It’s going to look different. This dialogue style captured that difference in a visual way. When we saw how different it was from normal dialogue, we subconsciously imagined the alien. Which was cool.

But the dialogue was hard to read. The middle part often covered the regular text on either side, which meant I had to squint and move the page around to see what the alien was saying. James also fades the regular text out as the script goes on until it’s practically invisible. So I wasn’t sure if that text even mattered?

Finally, I wasn’t sure how I was supposed to interpret the dialogue. The middle section always contradicted the ends so… I guess that meant the alien was always lying. But it’s still spoken dialogue so didn’t that mean Lee could hear it? All in all, as creative as it was, I felt it was more trouble than it was worth.

The script’s strongest suit is its emotional core – the relationship between Lee and Blair. But I’ll be honest, I had trouble giving in to it. For starters, they’re both late 20s, early 30s. And Blair has dementia. It didn’t read right. A 28 year old with dementia? I’m sure it happens but it happens rarely enough that it creates that dreaded “reading hiccup.” And then the characters called each other Mama Bear and Papa Bear, the kind of nicknames old people use for each other, which confused me, because these characters were young. It just created this clunky vibe to the proceedings that prohibited me from fully enjoying what I was reading.

And while I don’t mean to pile on, this script doesn’t resolve my belief that you can make aliens scary in the way that you can make traditional earthbound creatures and monsters scary.

What happens in The Harvester – and what happens in a lot of these scripts that try to combine horror and aliens – is that, at a certain point, the writer learns that making them scary doesn’t make sense. So it always turns out the the alien is helpful instead of hurtful. We see that here with the alien offering his magical medicine that can heal anything. And, at that point, what are we scared of? We’re not. In retrospect, I’m not sure I was ever scared. And I’m someone who routinely watches scary movies through my fingers.

I mean how scary of an alien can you be when you’re easily restrained by handcuffs? It just didn’t make sense. And I don’t want to dog James because I’ve been down this road before myself. With my own alien-horror scripts which ran into this same problem, and with scripts from other writers that I’ve tried to shepherd. But none of them can ever quite figure out this “aliens being scary” thing. You can do it in flashes. But over the course of the story, it doesn’t make sense for aliens to be scary. Why come 100 light years if you’re going to hide underneath beds and say “boo?”

Overall, as hard as I tried, I couldn’t connect with this script. The horror wasn’t horrifying enough. The sci-fi hit a wall. And the drama was affected by little choices that resulted in an unnecessarily clunky relationship journey.

It wasn’t for me but I’m curious what all of you think. Check out the script below.

Script link: The Harvester

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Whenever I see a writer offer three genres for their script, the first thing I think is, “This writer doesn’t know what kind of story he’s telling.” And that’s how I felt when I read this. “I’m not sure this script knows what it wants to be.” It leans most heavily into the drama side of things. That’s when it’s most comfortable. Cause I think James understood that storyline the best. But this alien who’s sort of dangerous but not really dangerous dictating the majority of the narrative had me scratching my head. It just felt like there was a better story that could be told here. And my gut tells me simplifying the genre is a good place to start.

I stumbled across this video recently while performing a most impressive act of procrastination. I was half-listening at first but as Gervais’s calm soothing British tone gesticulated across me, I found myself subconsciously nodding. I restarted the video and listened more closely.

I’m convinced that what Gervais says here is the single most important factor to writing things that people care about. So much so, I would argue that nobody reading this article today can become a professional writer until they go through this transformation of understanding. They have to accept it, understand it, then execute it, so they can graduate to the other side.

To give you the TLDR of the video, Gervais says that he started out writing fun silly stuff – cop movies where the cop “didn’t play by the rules.” And whenever he turned these scripts into his teacher, the teacher would tell him, “This isn’t any good. Write what you know.”

But Gervais was convinced that people didn’t care about boring truthful everyday stuff. He wanted the fun stuff. The stuff that’s on TV. The stuff he saw in the movies. So he kept writing what he wanted. And he kept getting bad grades.

Finally, he figured he’d pull a fast one on the teacher. As it so happened, every day, his mother would go next door to take care of an elderly woman and sometimes Ricky would go with her. It was the single most boring thing you could write about, in Gervais’s opinion. But it was something “that he knew.”

So he wrote about a day following his mom over to this elderly woman’s house. And he went into excruciating detail. He wanted to make sure that he was writing EVERY SINGLE THING HE KNEW about this experience in order to prove to his teacher that the teacher was wrong and that writing about this sort of thing only led to boring people to death.

I think you know where this is going. When he got the grade back, he’d received his first A. And that’s when the lightbulb went on for Gervais. It isn’t about all the fantastical larger-than-life craziness. It’s about humans connecting with other humans. You achieve this by writing what you know. And because you’re writing what you know, you are writing THE TRUTH. And THE TRUTH is the single most important part of getting readers to connect with your writing.

This isn’t the first time I’ve heard a writer share this story. I hear a lot of writers say this was the moment they finally understood writing. Neil Gaiman talks about how nobody cared about his writing until he started “telling the truth.”

But what is “the truth?” What does “the truth” look like?

It starts with, like Gervais says, “What you know.” For there is nothing you know more truthfully than your own life.

I used to teach tennis, as some of you know. So let’s use that as our theoretical backdrop. We’ve got Writer 1, who took a couple of tennis lessons when he was a kid and wants to write a movie about a tennis pro. Then we’ve got Writer 2, who taught tennis for ten years, and wants to write a similar movie (me).

The first scene of Writer 1’s movie is probably going to be our tennis pro showing up at the Beverly Hills Country Club or a similar upscale tennis place. He’s got his tennis whites. He’s got a 5 o’clock shadow. He makes some funny quips to a few co-workers, as well as the hottie tennis pro he’s dating. She asks if they’re still having lunch later. Of course. He rushes out to teach his first lesson, a sexy MILF who’s giving him googly eyes the second he steps on the court. He tries to teach her but she can’t help but make a bunch of sexual innuendos during the lesson. Afterwards, she proposes that all future lessons take place at her private tennis court. He has to practically slip out of her grip to get away from her. And that’s the first scene.

Now, let me tell what a morning with me was like as a tennis pro.

I would ride my bike to work because my car was always broken. I had timed it so I got to work at exactly 8am. That way I could technically say that I was on time, even though it would take me another five minutes before I got on the court and started my lesson, to a client who was in no way interested in or trying to flirt with me. They were just mad because their lesson was going to start late.

Now, I didn’t teach at Beverly Hills. I taught at Westwood Tennis. A park. Which meant that I would have to wake up the homeless person sleeping in front of the tennis shack door every morning and tell him to get out of the way so I could go inside.

After he took his sweet time, I would go inside and begin looking for the necessary tools I needed to teach my lessons. One thing you have to realize about tennis pros is that they’re always breaking their strings. Cause they’re playing all day. We all had 3 or 4 rackets but we would eventually break the strings on those rackets too. And since we’re all so lazy, we don’t get them restrung. Instead, we use the demo rackets, which we’re not supposed to use cause those are reserved for clients to help motivate them to buy said overpriced rackets. Since all the pros would snatch these demos – because they’re all breaking their strings too – the demo racket strings would break as well.

When this happened, we’d start using the kid’s demo rackets. These rackets were much smaller and way flimsier and, most importantly, they didn’t look professional. Half of them were girl’s rackets for 10 year olds that had Disney themes on them. Which meant that, it wasn’t uncommon for me to walk on the court with a tiny pink Little Miss Mermaid tennis racket. This when I would occasionally have to play with advanced players. That never went over well.

But the racket wasn’t even the main problem. The main problem was the tennis balls. All us pros were responsible for our own tennis balls. We had to buy them ourselves. And when you have to buy 50 cans of tennis balls at $3.50 a pop, that adds up. Especially when all of the annoying beginner players keep hitting the balls over the fence where they would vaporize to never be seen again. This would annoy me to such a degree that, for a while, I had a rule, that if any of my lessons hit the ball over the fence, they had to stop playing immediately and go retrieve it. They weren’t allowed to come back until they found it.

With the constant dwindling tennis ball supply there was a lot of ball thievery going on. If a pro had gotten so lazy as to not buy new balls in a long time, their ball cart wouldn’t have enough balls for a lesson. So if we were the one with the depleted cart (which I often was) we would steal balls from the other tennis pros’ carts when they weren’t around. Tennis ball stealing became so rampant that each pro started buying multiple locks to lock the top of their tennis ball carts so you couldn’t steal their balls

This never stopped me. I would reach my hand down through the sides of my fellow tennis pros’ carts, scraping the insides of my arms to the point of bleeding as I fished out one agonizing ball at a time until I had enough to teach my lesson. It got so bad that everyone would mark their balls with their initials in permanent marker. This did not deter me if I needed balls bad enough. You can’t show up to a lesson with 15 balls. You’ll be done feeding balls within 2 minutes.

I could go on. But I think you get the point. The first writer writes the generic version of being a tennis pro because they don’t know any of the truths that go into teaching tennis. They’ve never done it before. Whereas I have over a million unique details of what goes on as a teaching pro. And most of them are surprising. I doubt any of you would’ve guessed that that was an average morning for a tennis pro.

By the way, if you want to see a real world example of Writer 1 in action, go watch the pilot episode of “Based on a True Story” on Peacock. The main guy character is a tennis teacher and they write him almost exactly the way Writer 1 wrote it. There’s zero truth to it and you’ll notice how detached you feel from his tennis storyline for that reason.

I suspect this is why I hate shows like Ahsoka right now. I don’t feel any truth at all when I watch that show. Granted, it’s much harder to write what you know if you’re writing fantasy or sci-fi or an action film that takes place in Casablanca. You’ve never been to Casablanca so how are you going to make that sound truthful?

Well, the answer to that is, YOU’RE NOT. You really aren’t. No matter how hard you try. What you should do instead is pick a concept that covers subject matter you know well. The chances of you writing something that will resonate with others will go up exponentially.

But we also have to be realistic. Some writers like writing fantastical stories. And it’s unrealistic to think that you’ll never run into story sequences that don’t have some elements that you’re unfamiliar with. So what do you do if that’s the case?

The answer, believe it or not, is simple. While you won’t be able to write about subject matter that you know, you can always write CHARACTERS THAT YOU KNOW. And if you’re writing characters you know, the character side of your story will be truthful.

This is why it’s a smart idea to base your main character on yourself. Or some aspect of yourself. That way, you’ll be able to write them truthfully. I always tell writers, figure out what your biggest struggle is at this moment in your life. Then have your main character going through the same thing.

If you’re struggling through a hard divorce, your hero should be struggling through a hard divorce. If you’re struggling with belief in yourself, your hero should struggle to believe in himself. If you’re trying to emerge out of the shadow of a successful parent? Yeah, I think you get what you have to do.

Then apply this same approach to as many characters in the story as you can. Base some on other parts of you. Maybe there’s another part of you that’s frustrated that you can’t stand up for what you want. So give that flaw to a supporting character. And for the rest of the characters, base them on people you know or who you’ve met throughout your life. Figure out what represented those people and simply transfer it over to your characters.

If you can do this with your characters, you can write big elaborate screenplays and still have them feel grounded and truthful. Cause all your characters will act with an underlining sense of truth. And you’re writing what you know. If you want to see this in action, check out James Gunn’s studio movies. He’s good at writing gigantic fanciful movies yet still finding the humanity in all the characters. I’m convinced he does that by writing what he knows and always staying truthful.

I can promise you this. If you write a giant action plot for a subject you’ve never had any personal experience with and then you ALSO don’t build your characters around truth, your script is dead in the water. This is something all writers have to figure out if they want to write great stories.

So get to work!

And I’ll be back tomorrow to finally review our second place script for the First Page Showdown!

Oooh-oooh-ahh-ahh-ahhhhh. It’s that most gorrrriest time of the year. Which means, in addition to some eyeballs and fresh liver, I shall serve you a horrifying script review. As David Pumpkins would say… any questions??

Genre: Horror

Premise: Two young Indian brothers living in England head back to their dying grandmother’s home in a remote part of India only to learn that her house may be haunted.

About: This script finished on last year’s Black List with seven votes. The writer has worked on a couple of small movies as a crew member. He’s still looking for that first writing credit.

Writer: Vikash Shankar

Details: 118 pages

Ms. Marvel’s Rish Shah for Dev?

Ms. Marvel’s Rish Shah for Dev?

I chose this horror script today to get you in the Halloween Logline Showdown mood! Send me the logline for your Horror or Thriller script by next Thursday night. The five best loglines will compete over that weekend. It’s going to be a spoooooooooky fun time.

What: Halloween Logline Showdown

Send me: Logline for either your Horror or Thriller script (Pilot scripts are okay!)

I need: The title, genre, and logline

Also: Your script must be written because I’ll be reviewing the winning entry the following week

When: Deadline is Thursday, October 19th, by 10:00pm Pacific Time

Send entries to: carsonreeves3@gmail.com

Okay, onto today’s horror script.

We’re constantly told as writers to bring the reader somewhere new, somewhere fresh. And yet, often times, when we do that, the feedback we receive is, “It’s a little too out-there.” “It’s too inaccessible.” “Not marketable enough.”

Today’s scripts is the perfect example of that. The writer is doing what you should do, which is find a new avenue into the horror genre. Take us somewhere unique. Because that’s where you’re going to find all the fresh scares.

But I’m guessing that the majority of you saw this logline and thought, “Ehh. Not interested.” “A horror story set in India? Not my jam.” I know this because it’s the reason it’s taken me so long to review it. Whenever I see the logline on the Black List, one of those two thoughts pops into my head and I move on. Which is why choosing a concept as a writer is so hard. You’re trying to hit that elusive target of “fresh but familiar.”

The good news for the writer is that it’s still horror. And horror sells. So if he’s a good writer and he’s come up with a scary story, he can overcome our bias. Let’s take a look.

Dev, 18, and his little brother Sid, 13, live in London circa 1989 at a foster care home called “Bring Them Home.” Dev is at the end of his foster care service and is desperately working the government system to get custody over Sid so that they can live together.

That’s when Dev learns that their grandmother, who lives in India, is clinging to life, which means that they may be inheriting money. This would solve Dev’s problem of taking Sid out of foster care. So the two head out to Varanasi, India to their grandmother’s place, a large rural farm house.

Once there, Grammy dies pretty quickly and Dev and Sid work with their aunt, Parvati, not related to the opera singer, to try and sell the house. As we’ve established, Dev needs that money badly. The problem is that the villagers in the area all think the house is haunted.

This is where Dev and Sid learn about why their parents got rid of them. Long story short, there used to be a lot of child labor here and the parents were afraid that Dev and Sid would be sent off to work the fields their whole childhood. Which is a load off of their backs since they always assumed their parents hated them.

It turns out their parents story is a lot more complicated, though. The land they’re on is sacred and a lot of the neighbors thought that, if they sacrificed their own children on the land, that God would look over them. So there were a lot of child sacrifices here. Their father, in an attempt to stop it, burned everything, including his wife. It looks like something survived this burning, though. Something evil. Something that now wants to claim Sid.

One of the great things about horror movies is that if you’re clever with your soundtrack and your cinematography, you can hide a lot of script problems. You can literally loom on a shot of a church from a low angle for 60 seconds, with a slow zoom-in, accompanied by some “Exorcist-like” piano chords, and you look like the most visionary director ever.

I get the sense that this script was designed under that principle. It wants to be a movie first and a script second.

Unfortunately, that’s not how it works. The script always comes first. That’s where you build your story. But Shankar is so into the details of his world – the imagery that is going to make the movie look so great – that he forgets to move his story along at an acceptable pace.

There’s a moment on page 56 where the priest, Anand, has Sid and Dev grab a giant pot and perform an elaborate fire ritual with it.

He tells them, “The soul’s liberation from its physical form in this life and the next. It can take its rightful place in the Cosmos knowing its fulfilled its duties here on Earth.” Sid looks at him inquisitively. “Didn’t we already do that?”

WHICH IS EXACTLY WHAT I WAS THINKING.

Just eight pages ago (!!!) we had a scene where they did a ritual with burning her body that helped her get to the next life or something. It’s the same scene!

You never want to repeat beats in a screenplay. I can’t emphasize how quickly the reader gets bored. If you’re going to repeat plot beats? You are opening the gates of boredom.

And, oh yeah, you read that right. We’re still dealing with the grandma’s death on PAGE 56!!!! We should be WAY PAST that by now. The grandma should be dead and gone by the end of the first act.

We need to start a mandatory course for all screenwriters going forward to read Scriptshadow. Because if they did, THEY WOULDN’T MAKE THESE MISTAKES. I’m saving your scripts from disastrous errors if you’d just listen!

The one thing the script has going for it is an extensive, and quite imaginative, mythology. Kudos to Shankar for conceiving of this child-sacrifice backstory as it is definitely not something I’ve seen before. But even that great part of the script is overshadowed by endless detail and lackluster pacing.

Something all horror writers should be aware of is that if you’re stuck in one location – which often happens with haunted house scripts – you need to move your plots along quicker because we’re going to get bored faster in contained locations. Characters sitting around is script ambien. So you need your plot to offset that.

Having your inciting incident – the grandma dying – on page 45 (and then lingering on the death for another 10 pages) is guaranteeing that the script ambien is going to set in.

I also thought Shankar missed some creative plot opportunities. Whenever you’re dealing with haunted house movies, you have to be able to answer the question, “Why don’t they just leave?” In this story, the grandmother screams at them to leave as soon as they come. Then dies under mysterious circumstances. Pavarati and his orchestra go tumbling down the stairs and almost die, also under mysterious circumstances. Sid seems to see a new monster every night when he goes to sleep.

So why is Dev staying? Especially since nobody wants to buy the house due to it being haunted.

A cool plot choice that Shankar could’ve used was to make the priest sketchy. For starters, you get irony, which is always great. Since the priest is the one telling Dev that he won’t be able to sell the house, Dev should think that the priest is lying. And that, as soon as they leave, the priest will take the house and sell it for himself. That’s why Dev stays. Cause he thinks he’s being played. The priest is lying about all this haunted nonsense so he can make some cash. This would’ve also given you more conflict to work with as well, which is great for any story.

Irony. Better Logic for why Dev stays. Conflict.

That’s three great things with just one smart creative choice.

I suspect, if Shankar is directing his script, that the final product will be better than the screenplay. But even if he directs the roof off of this thing, I don’t think the movie can overcome the leisurely-paced story. This script needs a faster pace to get the most out of the concept.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Action turbocharges description – “Dev and Sid fan themselves in the heat, glistening with sweat.” This is a good example of how to convey relevant description. You add an action to it. This line could’ve been, “Dev and Sid ride in the car, their foreheads glistening with sweat.” That tells us that it’s hot, yes. But there’s something about adding an ACTION that resonates more with the reader. That action of “fanning themselves” conveys how hot it is.

Genre: Action/Period/Heist

Premise: A unit in the American army in World War 2 goes AWOL in an attempt to steal looted treasure from a Nazi train.

About: This script sold for a million dollars back in 1989. Disney snatched it up the second they read it. Unfortunately, the writing team, Rick Jaffa and Doug Richardson, would nearly come to blows after the sale and never wrote another script together. But Richardson would go on to write Die Hard 2 and Jaffa would become one of the most successful screenwriters in the business. You may have heard of a little movie he penned called, “Avatar: The Way of Water.”

Writers: Rick Jaffa & Doug Richardson

Details: 128 pages

Suits’ Gabriel Macht for Mac?

Today we’re going to discuss an overlooked screenwriting topic – the faulty premise.

The faulty premise should be up there in the top 5 of every screenwriter’s “avoid at all costs” list. This is because a faulty premise cannot be fixed through rewrites. So what ends up happening is that you rewrite and rewrite and rewrite the script, to the point of almost perfect execution… but it doesn’t matter. Because the premise is still faulty.

We’ll talk about this in more detail after the plot synopsis.

It’s World War 2 and the tide is turning for the Allies. It’s looking like evil will be usurped. But that doesn’t mean there still aren’t a lot of gnarly battles going on.

We meet universal problem-solver and effortlessly cool, Mac Mccann, when he’s blowing up a train tunnel to stop any future Nazi trains from getting through. Mac’s superior, a guy named O’Connor, HATES Mac, mainly because Mac doesn’t play by the rulebook (he’s the only guy in the military with long hair) yet always wins in the end, getting all the glory.

After liberating a small Italian town, Mac and his unit – which includes Sewage (big and dumb), Hands (great with his hands), Lips (can talk himself out of anything), Rex (an actor), and Pope (religious) – have been revealed to have hit up a local Italian bank and stolen all their money. It turns out Mac and his crew are using this war to line their pockets.

So it’s not surprising when they hear that the Nazis are loading up on treasure from the Jews and anyone else they can steal from, that Mac has the brilliant idea to rob the train all this treasure will be transported in. This’ll ensure that when they get back stateside, they’ll be drownin’ in monaaaaaaay.

There isn’t much resistance from his crew so off they go – DIRECTLY INTO GERMAN OCCUPIED TERRITORY. This requires them to steal a German truck and dress like German soldiers. And it turns out that, except for Rex, none of these dingbats is very good at pretending to be German. They’re identified at the very first checkpoint they cross.

But they somehow escape, keep traversing, meet up with a marooned all-black tank crew, have to steal another tank from a local village, before they’re able to head the Treasure Train off at the pass and enact their final plan. But will they be able to execute said plan? And what happens when one of the cars turns out to be carrying something more than treasure?

Okay, did you note the faulty premise?

Actually, you should’ve spotted it in the logline.

You can’t have the primary goal of your heroes be to steal treasure that comes from innocent civilians in World War 2. Maybe you could pull it off if this was set in the modern day. But a lot of this is Jewish treasure. To have your heroes stealing from Jews in World War 2…. I’m sorry but there’s no way you can make us root for those characters. It’s too big a hill to climb.

The way you do it is the way Indiana Jones does it. He steals treasure and gives it back to its rightful owners.

Now, whenever I see a writer do this, they always try and backtrack later on in the script. So, in the case of “Hell Bent and Back,” once Mac and his team are on the train, they discover that one of the cars is full of children. Which leads to Mac having to decide whether he wants to save the children or take the treasure.

Of course, he chooses the children. And it’s actually a well-executed character arc. This guy has been all about the Benjamins for two hours. But he finally changes, realizing that helping others is more important.

The problem is, it doesn’t matter because you’re still subjecting the reader to two hours of your character wanting to steal Jewish World War 2 treasure for himself. You can’t make up for that.

Which is too bad because the script is actually fun.

It has a bunch of well-done set pieces. There’s an early one where Mac’s unit, dressed as German soldiers in their German truck, come across a checkpoint and the real Germans inspect the truck. The Germans suss out that something is off and the next thing you know, it’s complete mayhem.

I love when writers do this. Because what usually happens in the scripts I read is that the writer will protect his protagonists. He’ll make sure, when his characters get to this checkpoint, that the bad guys never get too close to figuring them out.

In writing, you never want to help your protagonists. If anything, you want to be your protagonists’s worst enemy. You want to make their lives a living hell. If they’re at a checkpoint, don’t take the easy way out. Have the Germans realize who they are. I guarantee your scenes will be way more exciting once you adapt that principle.

The script definitely has an old-school feel to it. In that sense, it does things that I miss. There’s this entire set-piece in a small town where Mac’s unit is trying to secure a tank – and the writers take their time, set it up, build it, cover it from multiple character angles – so by the time the Germans figure out what’s going on, it results in a giant climax that’s emphatically earned.

You don’t see that in today’s movies much. We move in and out of these big sequences without the requisite setup, without the use of suspense. It’s slam, bam, thank you crayola crayon, and, therefore, it feels empty. Like it’s over before it started. Don’t be afraid to build up your set pieces. The reader will afford you as much time as you want as long as we feel like we’re building towards a big cool moment.

This script reminded me of a really REALLY early prequel to Guardians of the Galaxy, as strange as that may sound. Mac is Starlord. Sewage is Drax. Lips is Rocket Raccoon. The characters even start out in prison. It goes to show how dependable this formula is. I just wish they’d have found a non-faulty premise. Cause that’s clearly why this movie never got made.

Script link: Hell Bent and Back

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: If you’re ever lucky enough to get your script as far up the food chain as Hell Bent and Back, one of the biggest things that will be scrutinized is: Will we root for these characters? And if the characters are doing something reprehensible, then the studios are not going to pull the trigger. It’s too risky. If you want to write more interesting material where your heroes exist in that moral gray area, that’s fine. But you’ll have to write stories that have a much lower budget. Cause if you’re writing something that costs as much as Hell Bent and Back? I guarantee you they want their protagonists to be likable.

So I’m sitting there watching Talk to Me, the A24 Australian horror movie you might have seen the trailer for. It’s the one where a bunch of teenagers are in a basement and one of them holds a hand statue and then goes into some sort of trance.

The movie is pretty good. But it made its fair share of screenwriting errors. Basically, the plot goes like this. A teenage girl, Mia, hangs out with this family all the time because her mom died. She’s got her friend, Jade. And then Jade’s younger brother, Riley.

This trio occasionally hangs around a cool group at school, led by tough-chick Hayley, and Hayley’s muscle, Joss. This group loves to play this game called, “Talk to Me,” where they bring out a hand statue, strap you into a chair in front of it, you hold the hand and say, “Talk to me,” then follow that by saying, “I let you in.”

As soon as you say, “I let you in,” whoever’s in the chair sees a [usually gruesome] dead person sitting in front of them. Nobody else in the room can see this. Just the person in the chair. This creates a level of doubt where everyone can write the experience off as fake, much like when two people push the planchette on a Ouija board. You can always blame the other person as the pusher.

Except everyone in the room participates in the experience so that sort of negates the idea that they’re faking it. But we’re not going to nitpick.

Mia seems particularly affected by her experience, where she saw a couple of gnarly dead bodies. But it’s when Riley goes under that the crap hits the air conditioner. Riley is channeling Mia’s dead mother.

Mia is so taken by the chance to talk to her mom that she prevents Riley from stopping the experience before the mandatory 90 seconds. Riley starts going ballistic, bashing his head into anything he can find, nearly killing himself before they’re able to detach the hand from him.

This results in Mia being banished from the family, which sends her back home to hang out with her dad. When Mia sees her mother’s apparition again, she finally answers the question about whether she killed herself. She didn’t. And the person who did is two rooms away from her. Her father. Time to run.

You may have snooped out a couple of the screenwriting issues from that synopsis. The first is that the possession rule is shaky. In fact, we’re not even sure people are being possessed for three-quarters of the movie. Mia is not possessed despite going through the process. She sees other spirits, like her mom. But she’s not possessed.

Then, near the end, we lean heavily into the injured Riley being possessed. And then, of course, Mia’s father being possessed. Whoever’s inside of her dad is trying to kill her.

You can tell that the writers started to realize near the end of writing the screenplay that, “Oh, they’re possessed! So we can do something with that!” So then they rush to pay off a possession storyline that they never really set up.

It’s fine to do this. It’s a natural part of screenwriting. You figure things out while you’re writing the script. But once you figure something big out, you have to go back and properly set it up.

Ditto the dad. They didn’t even mention the dad for the first 70% of the movie! I didn’t know she had one. How could I? She was always at this other house. And the writers leaned heavily into this idea that this other family was taking care of Mia. So we assumed she didn’t have family.

To not only tell us she had family, but to build the crux of Mia’s entire storyline around what her father did to her mother was clunky to say the least. A good screenwriter is going to realize that if they want to use this ending, they need to go back into that first act and properly set up the dad. Then keep him in the story throughout the second act.

As I was pondering all this, a question popped into my brain: Does it matter? Or, more specifically, would this have mattered in regards to how well the movie did? It’s got a 94% critic score on Rotten Tomatoes. It’s got an 82% audience score. It made 50 million dollars in the U.S. and nearly 90 million worldwide.

Would making those changes have affected these numbers in a positive way? Because if you look just at the movie, it’s really well put together. The main actress who plays Mia, Sophie Wild, is great. She’s going to become a star. The rest of the cast is really good. There are no weak links.

The cinematography is great. The directing overall has no weaknesses (they were particularly convincing in creating a “teenage atmosphere”). Also, the hand sequence WORKS. Whatever it is at the center of your fantastical story, it has to be convincing for the viewer to suspend their disbelief. If it’s hokey or dumb, they’ll immediately check out. And the “talk to me” stuff was perfect.

Most importantly, the movie was scary. I did the thing where I put my arms up in front of my face half-a-dozen times cause I saw something weird in the corner and it started moving and I didn’t want to know what the f*** it was.

So, if you do those things: You have a convincing mythology, you have plenty of legitimate scares, you have characters who we’re on board with – you can make screenwriting mistakes and it be okay. It’s similar to what I tell comedy writers. If your script is funny, you can have the worst plot ever. It doesn’t matter. Ditto with horror. If it’s scary, you can make mistakes.

But the purist in me still believes that if you fix those mistakes, your movie is going to have better word-of-mouth which means more people are going to want to see it. I think it’s telling that the audience score is lower than the critical score here. Audiences may have been a little frustrated by the sloppiness in the storytelling.

Look no further than what happened to Exorcist: Believer this weekend. Now I didn’t see the film. But I knew that the baseline they were building predictions off of was 30 million. Because that’s what the predicted ROI was for this particular advertising package. Now, the box office could go well above that number or below it. And it depended on if the story was good.

Guess what?

It wasn’t good. It has a 22% Rotten Tomatoes score and a 59% Audience score (which will probably go down once more reviews come in). It was made clear early on on social media that this one was a stinker. And so all those potential moviegoers who were thinking about going on Saturday who were going to pump up that box office to the high 30s, maybe even 40 million dollars, they decided to stay home, and the movie made 27 million bucks.

In David Gordon Green’s defense, I’ve never been able to figure out the key difference between an exorcism movie that works and one that doesn’t. For all intents and purposes, the original Exorcist should not have worked. It’s long. We’re stuck in this house the whole time. Some characters disappear for 90% of the movie. Others show up halfway into the movie.

I just remember that movie feeling so real. It felt like how an actual exorcism situation would happen. That realism is what sold it for me. And even though all these exorcism movies since have given us convincing possession performances, none of them has felt as authentic as The Exorcist.

In other words, trying to recreate the authenticity of one of the most authentic horror movies ever is a hard task to pull off. None of the other Exorcist sequels have been able to do it. I’m shocked, like the rest of the industry, that Universal paid 400 million for the rights to try and change that pattern. A lot of people thought they were dumb. Believer’s critical and audience reception is proving them right. It looks like this franchise is going to end up on the bottom of a concrete stairway.