The secret to writing a great screenplay with the least amount of effort.

Jayne Mansfield, star of the 1963 film, “Promises Promises”

Jayne Mansfield, star of the 1963 film, “Promises Promises”

I’m always thinking of new ways to crack the screenwriting code. Screenwriting is funny in that, at its core, it’s simple. Write a story with a beginning, middle, and end. Make sure it’s interesting. Voila. That’s it!

But like any skill, in order to attain mastery, it can get quite complex. I still remember when my first screenwriting teacher told me that each scene needed to achieve five different things. Pretty sure, in that moment, my brain short-circuited.

What happens to most screenwriters is that they start off believing in the former – that screenwriting is easy. They’ve seen movies. They know what movies they like and don’t like, so they figure they’ll write movies similar to what they like and that’s all you need in order to be a good screenwriter.

What happens to the majority of these writers is that their scripts don’t get any success or recognition and they figure that the system is rigged, probably to reward nepotism, so they peace out, never to write another screenplay again. Many of the remaining screenwriters become obsessed with cracking the code and, over the years, delve into the most minute details of the craft, figuring that if they learn EVERYTHING, they’ll be able to write a great script.

Most of these writers never return from that dark place. They just go deeper and deeper into the minutia, looking for the meaning of it all. I’m here to tell you that if you get trapped in that place, it’s just as hard to write a good script there as if you’re a beginner and think writing is easy. Down there, you’re writing from a place of technicality, which is hard to build a moving impactful story around.

Now let me be clear. I’m not saying all technical thought is wrong. There’s a mathematical element to screenwriting that cannot be ignored. The fact that you have to keep your story between 100-120 pages alone means you have to be strategic about how you plot, how you approach your character arcs, where you place your setups and payoffs. But we never want that aspect of your writing to impede upon the ultimate goal. Which is to write a great story.

Today’s article was born out of my newsletter article (sign up if you haven’t already: carsonreeves1@gmail.com) where I discussed “story engines.” This is the same idea but I wanted to make it even simpler for you. In fact, I would say this is the simplest strategy to create a good story. You don’t have to learn any technical terms. You don’t even have to know how to structure a script. As long as you follow this one rule, you can write a good screenplay.

Want to know what it is?

Promise.

No, that’s it. A promise.

All writing is is a promise. You extend a promise to the reader that if they keep reading, they will be rewarded.

Think about it.

Barbie is dancing at the beginning of Barbie, living her best life, when she freezes and asks everyone, “Does anybody else here ever think about dying?” That’s a promise. It’s a promise because we now want to find out why Barbie is having these thoughts. To prove why this promise works, imagine if Barbie had never vocalized these thoughts. She just goes about her perfect day and then goes to sleep. Why should we keep reading?

Promises can be big. They can be small. As long as there is at least one compelling promise in play at every stage of your story, the reader WILL TURN THE PAGE. Let me say that again. As long as at any point in your story there is a compelling promise that has been made, the reader will want to find out what happens next.

What does a bad promise look like? “Here’s a funny character.” That’s not a promise. The character may be funny to you but who knows if it’s funny to others. So we might not want to see any more of them. Remember, the key to the “promise” strategy is that we want to turn the page. If the promise isn’t good enough for that, the strategy won’t work.

So what are some actionable promises to keep the reader reading?

A dead body – This is one of the strongest promises you can make because who doesn’t want to find out who killed this person? Or why?

Will these two people get together? – We were talking about this in the story engine article. One of the early promises in Killers of the Flower Moon was, “If you keep watching, you’ll get to find out if these two get together or not.” This is one of the most often-used promises in the trade.

Will these two people resolve their issues? – This is popular in the team-up genre. Two characters who don’t get along are forced to team up with one another. The promise is that if you keep watching, you get to find out if they eventually find peace with one another.

Promises can be more immediate as well. And should be, depending on the situation. Early on in screenplays, the reader’s attention span is shorter. So you should be looking to introduce promises that have quicker resolutions.

A trained killer gets locked in a room with a group of thugs (The Equalizer). The dramatic irony is through the roof here (we know the thugs are in a lot of trouble) so the promise is strong. We can’t wait for him to kick their a$$. How do I know this promise is effective? Because I know every single one of you reading this right now would turn the page to find out what The Equalizer does to those thugs.

One of the most powerful promises is a strong mystery. I was just watching the pilot episode for the show, A Murder At the End of the World. Early on, we see a couple discover a dead body and then (spoiler) the killer catches them in the act, raises his gun to shoot, but before we show what happens, we cut to the present day. We know one half of the couple, the girl, is still alive, since she’s talking to us. But there’s no mention of what happened to the boyfriend. Was he shot that day? That’s a promise that the writer is making to you. “If you keep reading, I will answer that question.”

Later still in the episode, a man shows up at the woman’s door and says that she’s invited to meet one of the richest men in the world. Another promise. If you keep reading, you get to find out who this man is and why he’s inviting her.

You should have multiple promises going on at all times. They shouldn’t all be giant promises (a girl is possessed, a billionaire is murdered, a man is still in love with his girlfriend after spending 42.6 years in cryogenic stasis) or the promises will compete against each other. But you should be injecting smaller promises on top of your larger promises. I call this “layering.” Because you want the reader to stay engaged in the short term. So you make these immediate promises (The Equalizer just got locked in this room with these thugs. I promise you that if you keep reading, I’ll let you know what happens within the next two pages).

Just like all of writing, there is subjectivity involved in how compelling a promise is. You may think I want to learn more about how all this plastic got into this whale’s stomach, but you’d be wrong. So you’re always gambling in that sense. Which is why you want to lean into the types of promises that have proven to work over time.

Compelling mysteries, whodunits, will-they-or-won’t-they-get-together, unresolved relationships, a loved one has been kidnapped.

Here are some promises from popular movies throughout the years:

An alien is after me: No One Will Save You

Bank robbing brothers are trying to stay one step ahead of sheriffs: Hell or High Water

A giant shark is terrorizing the beach, killing everything in its path: Jaws

A dangerous violent man is coming unhinged: Joker

A man is erased from existence and sees what the world is like without him: It’s A Wonderful Life

People are stuck in a dangerous video game: Jumanji.

In each of these stories, a giant promise is made that makes it nearly impossible for us not to want to keep reading. Now, of course, you do have to write compelling characters for this strategy to work. But if you can do that, you can basically keep a story going forever. And if you think that’s not true, let me point you to Marvel, to Fast and Furious, to Star Wars, to your favorite TV show. Those stories go on and on and on without any real end because the writers keep making compelling promises. Marvel does so at the end of every movie with their post-credit scenes. Now you can do the same. And reap the rewards from doing so. :)

Hey! You want to get a screenplay consultation from me? You should! I’ve read over 10,000 screenplays. I’ve seen every trick in the book. If there’s anyone who can help you turn your screenplay into the masterpiece you and I both know it can be, it’s me. And if you mention this article, I will take 40% off my pilot script or feature screenplay rate. Just e-mail me at carsonreeves1@gmail.com!

Is 42.6 Years, from the co-writer of “The Menu,” the next “Passengers?” (The script not the movie)

Genre: Sci-Fi/Rom-Com

Premise: After waking up from a failed experimental lifesaving procedure in which he was cryogenically frozen for 42.6 years, a young man realizes he wants his ex-girlfriend back. He’ll have to overcome the fact that while he hasn’t aged a day, she’s lived an entire life without him.

About: This script finished on last year’s Black List and comes from Seth Reiss. You might recognize Reiss’s name as the co-writer of The Menu. He also wrote another weird script I reviewed on the site called, “A Big Bold Beautiful Journey.” The movie will star Andy Samberg (who came up with the concept) and Jean Smart, who stars in, “Hacks.” Craig Gillespie, the director of “I, Tonya,” and more recently, “Dumb Money,” will direct.

Writer: Seth Reiss (story by Reiss and Andy Samberg)

Details: 122 pages

I have a question for you. What’s the difference between a romantic comedy and a comedy with romance?

Is Jerry Maguire a romantic comedy or a comedy?

I thought about that after reading this script. I think it’s a romantic comedy but I’m not sure. You might be able to convince me that it’s a comedy.

Oh, by the way, we’re getting close to my year end RE-RANKING of the previous year’s Black List. This is where I tell you guys what the real rankings should be. Not the fakey rankings that all the agents and managers manipulate.

I’m not going to get to read every script on the list. There are some I know it will be impossible for me to like. But I’m curious which ones I should read before making the list. If you’ve read any of these scripts listed below and liked them, please tell me in the comments section, as I’ll want to check them out.

Himbo

Black Dogs

Eternity

The Seeker

The Trap

Caravan

Cheat Day

The Homestead

The Twelve Dancing Princesses

I Love You Now and Forever

You’re My Best Friend

Okay, onto today’s review!

It’s fifty years in the future, New York City, and 30-something Ben is breaking up with 30-something Ruth. Don’t get Ben wrong. He still loves Ruth. But Ruth’s issue is that she is the most unemotional person on the planet. The woman doesn’t have an emotive bone in her body. And it’s driven Ben crazy.

Immediately after Ben dumps Ruth, he finds out he has a rare disease and will die within a year. So he agrees to a cryogenic stasis – for exactly 42.6 years – in the hopes that when he wakes up, the disease will be cured. So that’s what Ben does. He freezes himself for 42.6 years.

Unfortunately for Ben, when he’s unfrozen, they still haven’t figured out how to cure his disease. Cured cancer, though! So that’s cool. For the folks with cancer. Feeling all nostalgic, Ben goes to visit Ruth, who’s now in her 70s, and is pleasantly surprised to learn that she’s single. So Ben makes a move.

The two start hanging out together again. They even have dinner with Ruth’s jealous ex-husband and her adult son. But Ruth is still having issues emoting. And it’s, once again, driving poor Ben nuts. Can’t this chick give him anything??

Eventually, Ruth learns that *SHE* has an incurable disease. Ben is shocked when she decides to use the exact same cryogenic procedure that he did. Which means she’ll be gone for 40+ years. Ben lets her have it. What is the point of doing this?? Why not spend her last moments here with him? But she’s defiant. She’s freezing herself. Unless… unless Ben can convince her with one last grand proposal.

The title of this script tells you a lot about what to expect.

It stems from the doctor explaining to Ben how long he needs to be in cryo-sleep before his disease is cured. When Ben presses the doctor on how he can possibly know it will take exactly 42.6 years, the doctor concedes that he doesn’t know. It could very well be cured in half that time. But he wants to play it safe.

Much of the script plays out with similar ambiguous logic. Ben glides through the randomness of this future where every apartment comes mandatory with its own French chef hologram. This sort of ambiguity usually bothers me but, somehow, Reiss makes it work.

I’ll often reflect on why something bothers me so much in one script while not bothering me in another. A lot of it, I presume, has to do with the way the writer writes. Reiss is so comfortable writing in this casual style, so confident, that I just believed it. It didn’t feel sloppy. It felt like a deliberate choice.

The humor here is specific and, just like all comedies, you’re either going to like it and, therefore, like the script, or roll your eyes and think the script is terrible. Here’s a little dialogue sampler. This is when Ben comes over to Ruthie’s house for dinner and meets her ex-husband and son.

It was probably inevitable that I would like 42.6 years seeing as it nails one of my concept prerequisites: whatever genre you write in, come up with an idea that allows you to explore it from a fresh angle. Here, we have a romantic comedy whose premise sets up a scenario whereby a 30-something man is dating a 70-something woman.

How many romantic comedies have you seen with that setup before? There’s Harold and Maude. There’s the cinematic classic, “Hello, My Name is Doris.” And I think that’s it. And this concept sounds way more interesting than both of those.

What surprised me about the script is that it manages to tackle pretty deep subject matter (getting old, dying) without ever getting depressing. The setup really helps in that sense. It’s so goofy that it offsets a lot of these conversations that, if they were had in a traditional movie setting, would feel depressing as hell. Yet “I’m going to die at the end of the year and there’s nothing I can do about it” registers only as melancholy in 42.6 years, since it’s often sandwiched between jokes.

The writer does make one unfortunate mistake, which is that Ruthie is borderline impossible to root for. She’s so selfish. She gives poor Ben nothing. Ever. Not even an, “I love you.” Here’s a perfect example. Before the dinner scene with Ben and her son and her ex-husband, Ruth is trying to figure out what to make. This is her thinking: “I know Ben likes Italian. So I’m thinking sushi so he doesn’t feel too comfortable.” This woman is straight up cruel.

It’s that age-old screenwriting dilemma of creating a character with negative traits that need to change but not making them so negative that we dislike them. It’s a fine line to walk. I always say, if you’re unsure whether your character is on the right side of that line, give them one extra positive trait for insurance purposes. For example, Reiss could’ve made Ruth funny. If I’m laughing at the things that she says, I’m much more likely to overlook her selfishness.

In the end, I liked 42.6 Years. It’s a tad too melancholy, particularly in its final act. But there’s more good here than bad. Ben is easy to root for. It’s a unique concept. Reiss did an understated but effective job of world-building here. For my money, I prefer the other high concept sci-fi comedy on this list – Dying For You – But 42.6 Years is pretty good.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Your script should be 110 pages or less. Ideally, it should be between 100-110 pages. That’s the sweet spot. However, if your script is all dialogue, like this one, you get 10 extra pages. That’s why I’m completely fine with this script being 122 pages. It was all dialogue so it read fast. Here’s a pro-tip, though. If you’re going to do this, make sure you’re giving us ONLY DIALOGUE starting page 1. Cause the second the reader sees that number – 122 pages – they will hate you. I’m serious. They will. They will grumble and shift around and mutter to themselves things like, “Who does this writer think he is?” But if you start right away with straight dialogue so that their eyes fly down the page, they’ll forget all about hating you. And if you do your job and write a great script, they’ll love you.

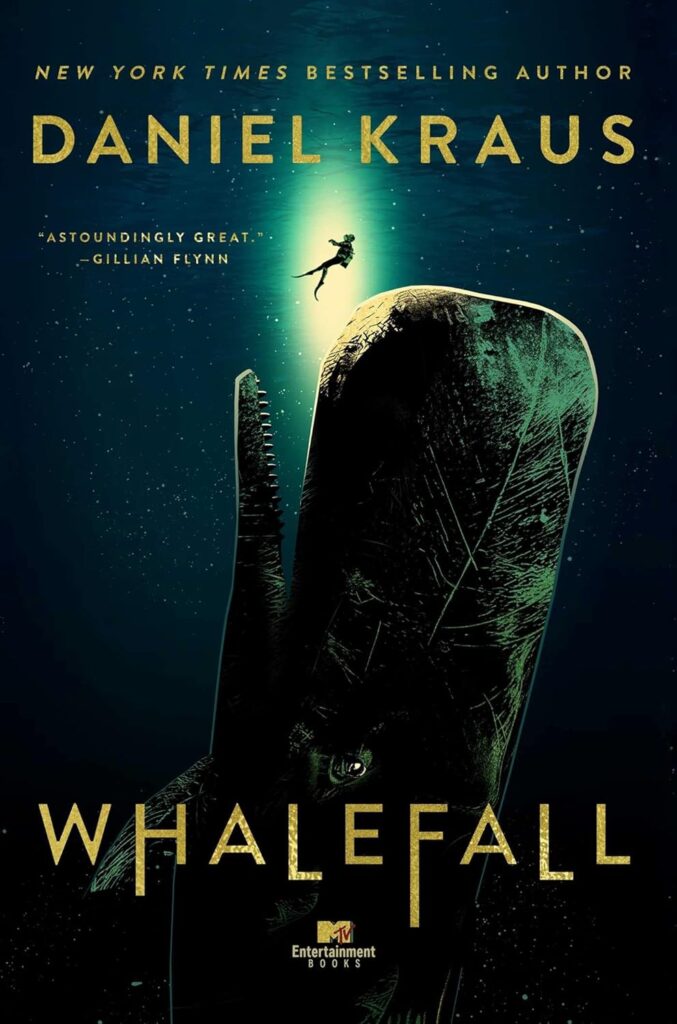

Genre: Contained Thriller

Premise: A young diver heads deep into the ocean to try and retrieve his diver-father’s remains but in the process gets swallowed up by a whale and has the time it takes for his air to run out (roughly 2 hours) to escape.

About: The rights to this novel sold to Imagine Entertainment (Ron Howard) earlier this year. Novelist Daniel Kraus is best known for writing the novelization of “The Shape of Water,” which would go on to win Best Film, after helping del Toro come up with the original concept for his movie. Kraus has a keen eye for picking ideas that both have a level of depth to them but also contain the marketable elements that Hollywood likes. Maybe the coolest thing he did was, after George Romero’s death, completed his unfinished zombie book, “The Living Dead.”

Writer: Daniel Kraus

Details: about 50,000 words (roughly half of most novels)

When I first saw this sale, I thought, “This is the kind of project that would’ve sold as a spec script back in 2004.” It has that “strange attractor” (a man being swallowed by a whale with only 2 hours of air). It fits inside a cost-efficient marketable genre – contained thriller. And it’s not like anything else out there. It’s almost like the Gen-Z version of Moby Dick.

But, unfortunately, these days, if you want to sell something like this, you gotta write it as a book or a short story (ironically, “Whalefall” is both).

The book poses a unique adaptation challenge in that, despite this being a wacky idea, the setting is decidedly tame – we’re inside a stomach the whole movie. I like to place myself in the producer’s stomach for purchases like this and try and figure out what their plan is. Do they stay true to the contained nature of the story and keep it in the whale’s stomach the entire time? Or do they take advantage of the illustrious and unique setting, occasionally taking us outside the whale?

Jay is 17 years old when he loses his father, Mitt. But don’t feel bad for Jay. Jay haaaaaaaaat-ed his father. His dad was a diver and a drunk. He was one of those crusty opinionated dudes who was friends with everyone but would also get into a fight with those friends at the drop of a hat. And he wasn’t a good father. The few times he did pay attention to Jay, it was usually to scold him for being girly or weak.

Mitt got cancer and, instead of fighting it to the bitter end, he took a trip out to where he felt most comfortable – the sea – and simply plunged off the back of the boat, sinking to his demise.

For reasons Jay isn’t even sure of, he decides that he’s going to dive into that same area and retrieve his father’s remains. Jay is not as good of a diver as his dad. But because his dad forced him into so many dives as a kid, he’s good enough. So away he goes, with about 2 hours of air, all by himself. Not advised, by the way.

Not long after he starts diving, Jay sees a fantastical sight. A sperm whale attacks a giant squid! The sperm whale only has one animal it is predator to and that is the giant squid. The squid tries to get away and, in the process, grabs onto Jay. The whale then eats the squid and, with it, Jay.

Jay soon finds himself in one of the whale’s three stomachs. Luckily, the squid gets sucked into another stomach. But it leaves a trail of bioluminescence, which lights up the stomach he’s in. Thank god cause I don’t know how they were going to light this movie otherwise (quick movie fact: The flashlights in Titanic were the sole historically inaccurate element but James Cameron used them because there was no other way he could think of to light the final rescue scene).

As the whale dives deeper into the ocean, Jay must figure out how he’s going to get out of here before his air runs out. Along the way, he develops a close bond with the whale, who is dying himself. Jay begins to see some similarities between the whale and his father, which will allow him, should he not survive this, to at least find closure with his father.

I gotta say: this was one weird book!

For starters, every chapter was 1 and a half pages. I’m not sure I’ve ever read a book with chapters that short. It made for a faster read (almost like a screenplay) but it led to an unfamiliar rhythm that I had trouble adjusting to.

One thing I liked, though, was it placed the amount of air (psi) at the top of every chapter. So it starts out as “3000” and then, with each successive chapter, it goes down. So we know exactly how much air he had left.

I bring that up because sometimes writers will assume that the reader knows things that they don’t know. I’ve read versions of stories like this where the writer didn’t give any indication at all of how much air was left, clearly assuming we knew. So you wouldn’t know if the character was totally safe or at the precipice of dying. I always have to remind writers: “If you don’t tell us, we won’t know.” All the better if you tell us in a creative way, which Kraus does.

Kraus also knows he’s battling his own whale here in that the location is limited. So almost every other chapter is a flashback to some moment in Jay and Mitt’s life. There isn’t any real story to these flashbacks. They’re just meant to fill us in – hopefully create a better understanding of their relationship so that we care more about it being resolved.

The author additionally understands that, even in book form, where it’s easier to ignore dialogue, that he needs some sort of interaction in the stomach. So he creates the voice of the whale, who starts talking to Jay. The whale is the most interesting character in the book. There was something very sad about the fact that it was dying and knew it.

That connection Kraus builds between us and the whale helps lead to the book’s best scene, when a group of orcas attack the whale. They know it’s old. They know it’s dying. So they go after it. But we never see it. We only hear it from Jay’s point-of-view. And then, what happens, is this really cool rescue operation by a group of other whales.

Unfortunately, outside of that great scene (and the initial whale-squid attack scene), there isn’t a whole lot here. I’m not even sure if the setup makes sense. First, you establish that this kid hated his dad. So why does he want to find his remains? And second, what are the chances of diving into the ocean and finding the remains of your father? 1 in 500 million? That never made sense to me.

Kraus is clearly searching for this deeper emotional connection between Jay, Mitt’s death, and the whale, but, if I’m being honest, it’s hackneyed. At first, the whale starts talking to Jay. But then, the implication is that it’s not really the whale who’s talking. It’s Mitt. But then there are clearly times where it’s the whale again. It all just felt very convenient. It was Mitt when the author needed it to be. It was the whale when he needed it to be. Readers and audiences don’t respond well to writing conveniences. It may make your writing easier. But it almost always makes the story worse.

Kraus also tries to shove in an environmental theme. It was actually interesting learning about how much plastic whales inhale because of all the litter in the ocean. But we’re already focused on this whole other storyline so it didn’t feel organic at all and seemed to support the idea that Kraus was never really sure what he was writing about.

We all have this issue in the early drafts of our scripts. You’re not quite sure what your screenplay is about yet so you add a bunch of ideas and a bunch of themes. But that’s what rewrites are for, to weed out the stuff that is no longer relevant. I suspect that because this novel is so short as is that Kraus didn’t have the option to get rid of the environmental stuff because he couldn’t afford to. It would’ve made a miniature novel even shorter.

Regardless of the fact that I didn’t love the execution here, I’m still intrigued to see what they do with the movie. It’s too unique of an idea for me not to be curious. Best case scenario, we could be looking at the next Life of Pi, which was a good movie.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: You have a couple of options when you do the death of a loved one in a story. Option 1 is that they really loved each other. Option 2 is that they had a contentious relationship. In my experience, option 2 is the better way to go, as was the case in this book. For whatever reason, if your two characters loved each other, it feels too much like a love-fest and therefore inauthentic, potentially even melodramatic. Whereas, if there was contentiousness between them, it feels more like real life. Also, there are more complex emotions involved in option 2, which tends to make the character who matters (our protagonist) more interesting. If our hero loved the person who died with all their heart, and that person loved them, then it’s just straight sad. There’s not a whole lot to do with “straight sad.” I’ve seen option 1 work well for secondary characters, like Sean in Good Will Hunting. But not with primary characters.

Today’s script uses one of my favorite framing devices in all of screenwriting. Oh, and Andrew Kevin Walker is back!

Genre: Drama/Thriller

Premise: After one of the world’s best assassins fails to kill his latest target, he must endure the devastating repercussions from his handlers… unless he fights back.

About: It’s finally here! This was the re-team-up I’ve been waiting for. Andrew Kevin Walker, the writer of “Seven,” and David Fincher, arguably the best director in the world. The film debuted this weekend on Netflix.

Writer: Andrew Kevin Walker

Details: about two hours long

No, it was not on my 2023 movie bingo card that David Fincher’s next movie was going to be his take on John Wick.

You know, sometimes you cry out to the screenwriting gods and you ask them, “Why do you not giveth in 2023? Why do you only taketh away?” And the movie gods came back and they say, “I’m sorry. I’ve been preoccupied up here. We had a writer’s strike. We had an actor’s strike. I’m still hung over from that whole Covid thing. I haven’t been at my best. I read Scriptshadow every day, Carson. I understand how upset you are. So as a token of my appreciation, and as a big apology, I give you, The Killer.”

I was nervous going into this one. David Fincher lost his way with whatever that movie was he made a couple of years ago. Pretty sure Mank will be used by future psychiatrists to study the long-term effects of boredom.

So I didn’t know if Fincher just didn’t care about entertaining audiences anymore or he spent a night reading 1078 positive reviews of his movies in a row and became convinced he could make anything work, even a wandering narrative about a house.

Also, this project had next to zero promotion behind it. I don’t understand how the re-teaming of David Fincher and Andrew Kevin Walker has a zero dollar marketing campaign while that monstrosity of Marvel underachievement is blanketing every inch of ad space on my computer screen. I’m just gonna blame Netflix for that. They still don’t seem to know what a marketing campaign is!

Ironically, that helped my viewing experience. Because I had absolutely no idea what to expect from this film. Due to preconceived notions, I actually thought it was a movie about a serial killer. I figured if Andrew Kevin Walker wrote it and David Fincher directed it and the movie was called The Killer, it had to be about a serial killer. But it was not about that. It was about a hitman. And I would go so far as to say it’s the best hitman film made in the past decade.

We start out with our hero (“The Killer”) in an empty apartment in France keeping tabs on an apartment across the street. A rich businessman lives there. Over the next 20 minutes, The Killer takes us into his assassination routine, which basically amounts to: stay patient. Wait for your opportunity. And when the time comes: strike. Oh, and listen to good music along the way.

There’s only one problem. The Killer screws up and accidentally shoots the wrong person. This is the first time this has ever happened to him so he isn’t sure what to do. But he knows that it’d be better to figure it out while running. So that’s what he does.

Cut to Brazil, where The Killer heads to his wife’s house. But when he gets there, he finds out that she was attacked. Luckily, she survived and is in the hospital. He knows the truth. They came for him and when he wasn’t there, they tried to make it hurt. The Killer gets from his wife what little she knows about the attackers and then a different kind of killing begins – personal killing.

He heads out to different parts of the world – first to attack his boss, the man who ordered the hit, then to find the cab driver who drove his wife’s attackers to his home, then to the two attackers (a crazy scary roid-rage dude and a mysterious woman whose hair reminded the driver of a “a q-tip”). Each sequence is its own little mini-movie. And each one carries an intense determination. For the Killer wants to make sure that nobody – and he means nobody – ever gets a chance to kill his wife again.

So, what is this framing device I alluded to in the byline? A framing device is just a way to frame the story you’re telling. One of the most common framing devices is real time. It just means you set your story in real time. Since movies are generally two hours long, you’ve created a frame by which your story will take place in two hours time.

Today’s framing device is a little more complex. I call it the vignette framing device. It’s the device that Quentin Tarantino popularized. Instead of telling one long movie, you break your movie up into vignettes. The vignettes can be as long or as short as you want them to be. The reason it works so well is because it breaks your story down into more manageable chunks. Instead of having one long two hour movie, you have six 20 minute movies, as is the case here. And then, within each of those 20 minute chunks, you tell a more manageable story with a beginning, a middle, and an end.

The way that Andrew Kevin Walker does it is by isolating each vignette to a new city. So then, within each city, we got a new story. It’s like getting six movies for the price of one.

I loved the way Walker worked within these vignettes. Each one has a similar structure. He sets up a goal – usually an assassination. And then he builds up to that moment. This is an important part of maximizing any story you tell. You want to establish the goal and then build up to it. The build up portion is most effective when you utilize suspense.

Walker establishes this in the very first sequence. We see our hitman in an apartment across the street from his target and so we know what his ultimate goal is. But if he just shoots his target a second later, you wasted all of that potential suspense. By building up to that moment over time – and if you’re like Walker, and really know how to milk suspense, you can expand that time out for 15, even 20 minutes – you build a need within the reader to see them do the job.

Because you’re isolating the goal to the vignette, you can build suspense into the sequence itself. Contrast this with, say, a heist. If this same character wanted to rob a bank and the robbing of the bank occurred in the third act, you’re asking for a ton of investment from the reader without giving them much in return. There’s only so much you can do to keep a reader satisfied over 90 minutes without a payoff. But, like I said, if you’re using the vignette framing device, you can give them that payoff much sooner.

Now, it’s important that when you’re using the vignette system, you vary the vignettes. If each vignette is the main character sitting in a building across from another building, waiting for the opportunity to shoot his target, we’re going to get bored. So you just find different goals and different situations you can tell these individual stories in.

(Spoilers follow) For example, one of the vignettes has The Killer locate the cab driver who drove the attackers to and from his wife’s place. The Killer then gets into the cab, pretending he’s a passenger, and only once they’re on the move does he reveal who he really is. And now you have this vignette where he extracts information from the driver.

Later still, there’s a scene where he locates one of the passengers who attacked his wife and he simply shows up at a dinner she’s having and sits down across from her. The entire vignette is the buildup to him killing her. But unlike the other scenes, this one feels different because it’s taking place in a public setting with a character who is perfectly aware that he is here to kill her.

One thing this movie made me realize was that when David Fincher signs on to your script, that must be the single greatest feeling a screenwriter can have. Because his directing is so amazing that he makes every inch of the script 100 times better. I was watching this and listening to certain lines of dialogue and noted how if that line was in a different movie with a different director it probably wouldn’t work. But in a David Fincher-directed project, the line sounds amazing because his directing style is so impactful that you’re pulled all the way into every single moment and believe it no matter what.

Case in point, one of the hardest things to do as a screenwriter is write a fight scene that works great on the page. Every fight scene reads generically. I’m guessing that the fight scene written in this script was similar. But the way Fincher directed it was amazing. It reminded me of a much darker more artsy version of that Terminator fight between the Terminator and the T-1000 when they first battle at the mall. It had that same gravitas. Every throw seemed to move the frame. Every fist that landed felt like an earthquake. And my TV doesn’t even have good sound! I would go so far as to say this fight was better than any fight in any of the four John Wick movies. It hit me harder for some reason. It felt so real.

Back to the screenwriting. One thing that Walker did really well here was he made you wonder what was going to happen at the end of each vignette. Remember that if you build up to a moment for a very long time and that moment goes exactly how we thought it would, we’re going to be unsatisfied. So what Walker does is clever. In that opening sequence, after 20 minutes of our killer meticulously taking us through his perfected system of executing a kill, he screws up and misses his target.

Why is this so critical? Not only is it a surprise that creates a dramatic impact in the moment, but it now means that in every vignette going forward, we’re going to be unsure what will happen. We think he’s going to do his job, but since the writer has established that he can fail, we know that’s a possibility too. And when you have that dichotomy stuck in the reader’s head, your suspense works like gangbusters, because we truly don’t know what’s going to happen at the end of the sequence.

I was thinking all weekend about my Thursday article. I realized that I forgot one of the reasons screenwriting has dropped off and that’s that writers aren’t spending as much time on their scripts as they used to.

Remember, back in the day, any movie you saw had to go through an excruciating process of being vetted by dozens of people, all of whom expressed some level of doubt in the project. The script would then go back into the system to address those doubts and come back stronger. It was only once the script addressed the large majority of these issues that it was allowed to get a green light and get made.

These days, the need for product is so high, especially with all these streamers desperate for content, scripts aren’t being vetted and challenged as much. So we keep getting these “third-draft” movies. And believe me, they feel like third drafts.

This is the first script in a while where I can tell the writer put a maximum amount of effort into it. This feels like a screenplay that has been vetted. It feels like a screenplay that went through a lot of pushback before coming back better. And boy did it make a difference.

All of that leads to one of my favorite movies of the year!

[ ] What the hell did I just watch?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[x] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: The Vignette Approach is not all that different from the Sequence Approach. The Sequence Approach breaks your script down into eight mini stories, as opposed to one giant story. The difference with the Vignette Approach is that it’s less about blending each storyline in with each other. Which means it’s easier to do, because with the Sequence Approach, there is the additional challenge of making it not look like a Sequence Approach. You don’t have to hide the fact that your script is a series of vignettes and therefore you can just focus on making each vignette as good as it can possibly be.

It’s been many moons since I’ve last been enamored by a script. Or a movie, for that matter. It’s led me to question what the issue is. Is it everybody else? Do people simply not know how to write anymore? Or is it me? Have my standards become too high?

I’ll tell you what I’m scared of. I’m scared of becoming that Scriptshadow commenter who hates every movie. If I can no longer enjoy the movies I watch or the screenplays I read, then there’s no incentive for me to continue doing this. I’m not interested in having a website that craps on everybody. I want to spread LOVE! Not be a hater-potater.

And yet Hollywood is doing everything in its power to lure me into a hate cocoon. I commend the Marvel marketing team for their Herculean effort to convince people that The Marvels is actually good. I’m assuming they sent Chris Hemsworth out to spend a day with every critic who gave this film a fresh score on Rotten Tomatotes. But come on, Marvel has known for a year that they’re dealing the cinematic equivlanet of fentynal. It’s insulting to sell us that this movie is actually watchable.

Then we get this new Ghostbusters trailer. What is going on here?? It’s a movie about an ice villain??? Did they accidentally swap with one of Marvel’s scripts? We’ll find out a year from now when Marvel releases Ghost Thor: Who Ya Gonna Call.

I haven’t even enjoyed the Star Wars offerings. You know what’s sad (or awesome, depending on your point of view0? One of the ways I wind down is watching Youtube videos of people watching the original Star Wars for the first time. It’s so addictive seeing them experience this wondorous perfect movie for the first time ever. And every time, without fail, they always get excited at the right moments. They laugh in all the right places. In a way, it’s like I’m watching Star Wars for the first time as well.

But these days, the serious Star Wars TV shows (Andor) don’t work for me. The silly ones (Ahsoka) don’t work for me. That Madalorian episode with Lizzo and Jack Black very well may have heisted my soul and sold it on ebay for Yoda earings.

I haven’t even been able to enjoy the Oscar-hopefuls – Oppenheimer, Killers of the Flower Moon, Barbie – which are supposed to be the projects that actually put time and effort into their screenplays.

So I think about this question a lot. Are my standards for screenwriting so high, at this point, that they can no longer be met? I’m biased but I don’t think they are. Still, several things have happened in the industry that have really hurt screenwriting in the past decade.

One of the issues is we don’t have that central screenwriting teacher anymore. In the 80s and 90s, it was Syd Field. In the 2000s, it was Blake Snyder. But once the internet popped up, writers stopped reading complete books on how to write screenplays and, instead, piecemealed their screenwriting education together through online screenwriting articles. So they know certain things (add conflict to your dialogue!) yet are totally clueless to others (how to build a compelling second act).

In addition to this, feature screenwriting moved away from singular protagonists trying to achieve a goal – the purest form of storytelling – to the “Marvel Ensemble” model where the writer is juggling 10 different protagonists and their subsequent storylines. Which isn’t normal! That’s not a typical story anyone would tell.

Then you have the rise of golden era television, with 1000 shows on TV, so that’s where all the writers went. And what does television promote? The never-ending story. There is no climax, which teaches screenwriters terrible habits. Cause if you don’t have to end your story, you never have to think about where your characters are going. And when those writers dip their toes back in the feature space, they bring that issue with them. Their narratives seem flighty and aimless because that’s the only kind of story they’ve had to write!

In other words, NOBODY KNOWS THE BASICS ANYMORE. They’re just making sh*t up as they go along. Yesterday’s script, which barely BARELY got a “worth the read,” is a good example. The theme of the script is messiness. The messier the better. That’s not good screenwriting. Good screenwriting requires focus and structure and planning.

So what I thought I’d do as we head into the weekend is remind writers of the basics. It’s not that hard. It really isn’t. But if you’ve never learned these things, then you’re probably writing a lot of weak-sauce material.

1 – Give us a likable character. Introduce your character in a way where we like him or her. Or, at the very least, sympathize with them. For example, if a woman’s husband of 20 years just blindsided her with divorce papers, we will sympathize with her. The reason this is so important is because nothing you do after your protagonist’s introduction will matter if we’re not rooting for them.

2 – Create a problem. A story cannot start until there’s a problem. This is the thing that jolts our protagonist into action. Think about it. If there’s nothing that forces your character to do anything, then they won’t do anything! You don’t have a movie if your main character isn’t doing anything. In one of my favorite movies from recent years, Parasite, the “problem” is very simple. The family is broke. They have no money. They need a solution.

3 – The problem introduces the goal. Once you introduce a problem into your hero’s life, you’ve created the all important GOAL. Cause now your hero has to SOLVE THE PROBLEM. And needing to solve a problem is a goal. To use Parasite as an example again, the goal is to take over the rich family’s home.

4 – The goal gives you your stakes. The reason the goal is so important is because it needs to power you through your second act. If the goal is minor or flimsy, it won’t be able to achieve this. This is where STAKES come in. We have to feel like everything is on the line for your hero. If you succeed, you get everything. If you fail, you lose everything. In other words, the bigger the problem, the more impressive the goal, which means higher stakes, which means you have more power to drive the second act. And just to remind you, NONE OF THIS MATTERS IF WE DON’T LIKE YOUR HERO. Which is why getting number 1 right is so important.

5 – Throw obstacles in front of the goal – A goal, in and of itself, is boring. Where the excitement happens is when that goal is challenged. So you want to think of your second act as the “Goal-Challenging Section.” You want to throw a bunch of things at the hero so it’s hard for them to achieve the goal. The harder it is, the more we’ll enjoy ourselves. Cause think about it: how exciting is it to watch someone try to achieve their goal with only minor pushback? To use Parasite as an example again, the midpoint has this crazy psycho dude secretly living in the basement. Talk about a challenge. How do you take over a house when you have this other guy already living there?

6 – A challenged goal makes your hero stronger – The bonus of challenging your hero in their pursuit of a goal is that it BUILDS CHARACTER every time they overcome one of these challenges. And each time that happens, assuming you got the number 1 rule right, we will like your character even more. Cause we like people who take on obstacles and overcome them. You know your second act is working when our love for your protagonist is growing.

7 – Endings aren’t as hard as you think – A good ending is less about some inventive never-before-seen plot twist and more about your hero facing their flaw head on and overcoming it. The endings that stick with us have some sort of emotional catharsis. Again, you got to get number one right or NOTHING YOU DO in the third act will matter. But, if we like your hero, and we’ve seen them struggle throughout the second act, and they overcome their flaw in the climax (Rocky overcomes his self-doubt to go the distance in the championship match), that goosebump-laced rush will shoot through the reader. Always try and think of your climax as an emotional catharsis and not as the final piece to a plot puzzle.

These tips don’t cover everything, obviously. You still have to surprise us, make interesting creative choices, write good dialogue, have a couple of stand-out characters besides your hero. You’d also like to execute your story with a unique voice or a fresh angle in order to stand out from the pack. But if you follow the above seven tips, it’s really hard NOT to write a good screenplay.

As for whether I’m still capable of being impressed anymore, I already have 10 movies that are going to make my Best Movies of 2023 list. I already have 10 scripts that are going to make my Best Scripts of 2023 list. That’s 20 stories right there. Should I really be asking for more than that in one year? I don’t think so. That’s plenty. I guess I was hoping for more stuff to blow me away this year. But maybe that’ll come in 2024.

I offer feature screenplay and pilot script consultations – the best notes in the business. If you mention this article, I will give you a $150 discount. Your script doesn’t have to be ready yet to secure the discount. You can send it in at a later date. Just e-mail me at Carsonreeves1@gmail.com. Can’t wait to read your script!