I heard Charlize Theron gained 50 pounds to play the roll of Tully in the new Diablo Cody film, which comes out this weekend in an attempt to woo you away from your 17th viewing of Avengers Infinity War. It was a good script and the kind of movie that gets you talking afterwards. So if you’re in that chill indie-movie mood, I suggest you check it out, if only to get Hollywood to make something other than superhero movies. Cause if this trend continues, I swear to you, that might be all they make in 2019.

On to today’s scripts. An interesting batch! We’ve got the winner of the “Why Your Script Isn’t Getting Picked” post in The House on Snare Lane. A good old fashioned adventure film. And we’ve got a writer who really knows how to sell a full read (“There’s a huge twist at the end of Act 2 you’ve got to check out!”). As you guys know, the rules to Amateur Offerings are simple. Read as much as you can from each script and vote for your favorite in the comments. The script with the most votes gets a read next week!

And if you believe you have a screenplay that deserves Hollywood’s attention, submit it for a future Amateur Offerings! Send me a PDF of your script, along with the title, genre, logline, and why you think people should read it (your chance to pitch yourself or your story). All submissions should be sent to Carsonreeves3@gmail.com.

Title: Godhaus

Genre: Contained Horror/Thriller

Premise: A professional house-sitter is tormented by an omnipotent force during a week-long stay at a mountaintop chalet.

Movie Poster Tagline: VENGEANCE IS THE LORD’S, HE SHALL REPAY IT

Why You Should Read: I’m always on the lookout for odd or unique occupations, and one day I happened upon professional house-sitting. I did the research and discovered the possibilities were endless – as well as seemingly unexplored in film. So I developed the character of “Terry” but didn’t have a story to build around her… until months later, once I’d cooked up a separate idea about an Old Testament God exacting revenge on a single individual.

Then the question arose: why would our protagonist, Terry – so sweet she wouldn’t hurt a fly – be targeted for such extreme punishment?

Mix into a contained bowl, add a sprinkling of humor, a splash of twists and a dash of turns, and voilà! I’m curious to find out if Scriptshadowers enjoy the meal… or send it back to the kitchen while refusing to pay the bill and complaining to the manager about unfilmables.

Title: That House On Snare Lane

Genre: Coming of age drama

Logline: When, on the eve of its demolition, a grief-stricken boy and his friends investigate a haunted house, they discover long-buried secrets have a way of resurfacing and … just sometimes, turning a sense of loss into hope.

Why You Should Read: Last year you wrote two articles that especially struck a chord with me. The first was a list of movies that Hollywood would like to make a new version of (not a reboot, but an original new movie that captures a similar spirit to that existing movie). The second was about the power of ‘anchoring’ elements of your screenplay in your own experience. So, here’s my take on number 6 on your list – Stand By Me, anchored to an experience in my own childhood but extrapolated … and with a sprinkle of magic added because, well, the movies should be magical, right?

Title: Blood

Genre: Historical Adventure

Logline: Based on true events. After Charles II reclaimed the English throne, he confiscated the homes of his adversaries. He also pissed off the notorious Colonel Blood. Now Blood, seeking justice and reparations, leads a crew of fellow rebel activists in one of history’s most daring heists – stealing the Crown Jewels from the Tower of London.

Why You Should Read: I’ve been writing for nearly two decades, but have only been pursued it professionally in the past few years. I’m also an actor, director, and editor… it may sound silly but I love every part of the storytelling process. I don’t generally tend toward historical pieces, but the story of Colonel Blood was so compelling I couldn’t not write it. I’m rather proud of the script, but folks around town aren’t wanting to touch a period piece from an unknown writer (yet), so I’m having a hard time getting it read. And so I come to you… Thanks for the consideration!

Title: Typee

Genre: Action/Adventure

Logline: After jumping ship on a remote island, a sailor must escape from his new captors, a fabled tribe of cannibals named the Typee.

Why You Should Read: “Typee” was Herman Melville’s best-selling book in his life time, NOT Moby Dick. The story was a hit with audiences because it was written by a man who “lived with the cannibals.” Yet for some reason, Hollywood has continued to overlook this hidden gem, which has everything a big cinematic movie needs: unique setting, high stakes, lovable characters, mystery, twist and turns, and a dramatic ending. The truth is no one really knows about this book. Moby Dick will always reign supreme as the iconic Melville text, but Typee deserves some love, too. It would make a much better movie!

There was one big theme I noticed throughout the book: identity. During his adventures on the island, the main character always walks a fine line between engaging in the native cultural and rejecting it outright. He is afraid of losing his western identity, yet he is forced by his captors to participate in the rituals and ways of the Typee. I used this as a central point of conflict in the script.

One last thing. This script has a lot of what I call “Oh, shit!” moments. You know, when you’re reading a script and something crazy happens and you say “Oh, shit!” out loud. I really worked to put these moments in there because the original text didn’t have enough of them. There’s one particular “Oh, shit!” at the end of Act II that you really shouldn’t miss.

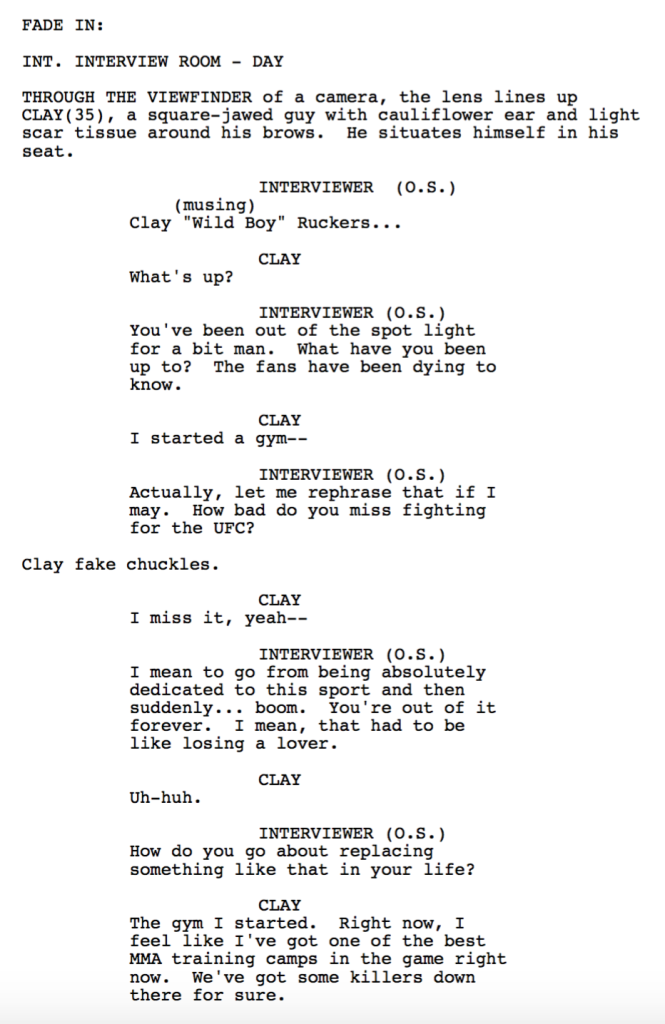

Title: Team Wild Crew

Genre: Action

Logline: A group of loyal, tight-knit MMA fighters, who train by day and rip off drug dealers by night, are charmed by a tough stranger looking to embed himself in their crew.

Why You Should Read: Three goals in mind when I was writing this: 1. I wanted it to be really, really bad ass. 2. I wanted the pace to be relentless. 3. I wanted to write an MMA script because I’m a huge fan of the sport and with Conor McGregor blowing the organization up, some writer is going to capitalize on it. So, why not have it be me? Anyway, The Fast and The Furious is essentially a remake of Point Break, right? Instead of the subculture being surfers we’ve got street racers. I thought I’d do a third reimagining, substituting surfboards and racecars for MMA and FISTS TO THE F*** FACE! Every script I write, I write for whoever’s reading it in mind. Enough of this “slow burn” crap– AIN’T NOBODY GOT TIME FOR THAT! One last thing– I got some coverage from WeScreenplay on this one. The reader ended it with, “easy recommend.”

We experience one of the most critical battles of World War 2, Dunkirk, from three different perspectives – on land, on sea, and in air.

A confused and frustrated Catholic School senior seeks to escape the boring town she grew up in and do something important with her life, all while coming of age.

Born with a facial deformity, a young boy is thrown into the biggest challenge of his life, going to public school.

A mother living in a small town erects three billboards that taunt the local sheriff into doing more to find the man who raped and killed her daughter.

A Navy SEAL sniper who attains hero status due to his legendary kill count on the battlefield struggles to find peace when he returns home from war.

The above loglines represent five films that either achieved commercial success, critical success, or both. However, if any of these loglines appeared on Amateur Offerings, I fear that they’d be ripped apart. Dunkirk sounds like a movie. But where are the characters? Lady Bird sounds like every coming-of-age movie ever. Wonder has the best setup of the five, but who’s going to make a movie about a kid with a facial deformity? Three Billboards doesn’t sound bad, I guess. But it feels like there’s something missing. And American Sniper sounds like every shitty “back from war” movie ever made.

The reason I bring these loglines up is because while we’re all searching for that perfect movie idea, the concept that’s tailor-made for a logline, the reality is that most script ideas don’t fit perfectly into a logline, or at least the logline Hollywood would prefer that we write.

For example, a logline LOVES a single hero. It loves when you can start with: “An archaeologist who moonlights as a tomb raider…” But what happens when your movie doesn’t follow a single character? What if you’re writing a logline for an ensemble, like the movie, “It?” Since you can’t describe every single character, you have to describe the group. This automatically forces you to be more general (“A group of misfits…”), which increases the chances of the logline sounding generic. What we tend to forget in the world of writing is that every story is unique. And therefore, each will have its own challenges when being summarized into logline form.

Hopefully I can make that process easier for you. Every logline has what I call “hotspots.” If you get the hotspots right, you increase the chances of the logline making an impact. What are hotspots? Well, the goal with every logline is to be SPECIFIC. The more specific you are, the more you’re highlighting what’s UNIQUE about your idea. There’s a problem with being specific, however. It leads to a longer logline. And the longer the logline, the uglier it reads. This presents the writer with a contradictory task. They must write something simple and quick, yet fill it with detail.

This is where hotspots come in. A hotspot is a point in the logline where important story information is being conveyed. There are three hotspots. They are:

1) The main character.

2) Major story beats.

3) The conflict.

The first one should be obvious. Whenever you describe your main character, you want to give us one or two adjectives (sometimes more) that make them specific. So you wouldn’t say, “A man attempts to resurrect his career…”. You would say, “A failed actor attempts to resurrect his career…”. Notice how much more you know about our character in the second example.

As for the second hotspot – major story beats – this is anywhere in your logline where you’re highlighting a major story development. There will usually be one of these in the logline, but there could be two, and sometimes even three. One of easiest ways to fail logline school is to not include any major story beats in your logline. Go back and look at my logline for American Sniper. There’s no major story beat included. The closest we get is “he comes back home from the war.” Talk about generic, right? No wonder the movie sounds so boring.

For those of you confused why I’m bashing a movie that made 300 million dollars at the box office, keep in mind that the logline was meaningless for that project. The movie was a success because everyone in middle America loved Chris Kyle and wanted to see a movie about him. But I’m getting off track.

Let’s use the logline from Molly’s Game to demonstrate what a major story beat is. “A former Harvard grad begins running a successful private poker game but finds her life turned upside-down when the FBI busts her for tax evasion.” The major story beat is “begins running a successful private poker game.” If you’ve seen the movie, you know that the logline is majorly underselling that point. Hence, we need to be more specific. How bout, “begins running Los Angeles’s premiere underground celebrity poker game.”

Bonus Tip: Loglines love words like, “Premiere,” the “biggest,” “greatest,” “all-time,” “most dominant.” The best stories are about extremes. So these words will serve you well.

My rewrite of that story beat seems obvious in retrospect. But I can’t tell you how many boring loglines I’ve read because writers weren’t able to sell those major story beat hotspots.

The third hotspot – the conflict – is the trickiest. This is because the resolution of your logline isn’t the resolution of your screenplay. It’s the main conflict in your screenplay. In other words, you don’t finish the Silence of the Lambs logline with, “And then Clarice kills Buffalo Bill and saves the girl.” You finish it with, “attempts to find the warped killer before he can finish the job.” The conflict in a logline is its resolution, and therefore will be what you finish your logline with.

Since there’s a whole lot to take in here, let’s use a lifeless logline as an example and apply our hotspot technology to beef it up:

A black man accused of killing a white cop goes on trial.

Okay, so this idea has potential. Let’s start with the first hot spot. “A black man.” That doesn’t tell us much. We need SPECIFICITY here. Notice how if we change it to, “A black law student with a checkered past,” the story already begins to take on new life. Now we know something about this “man.”

“Accused of killing a white cop.” This is a major story beat. Yet it doesn’t paint a picture. We need to dress it up. How bout instead we go with, “Accused of killing a white cop during a routine traffic stop.” (this is assuming this actually happens in your script of course)

Finally we have, “goes on trial.” This is one of the WORST logline mistakes I see writers make. They provide tons of detail in both the character and the major story beats. Then they tinkle out the conflict with so little conviction, it destroys any chance of a reader wanting to read the screenplay. The ending of a logline, which is you highlighting the script’s major conflict, should land with a bang. How bout, “must argue his own case in a predominantly white community determined to make an example of him.”

So let’s look at our new logline…

A black law student with a checkered past accused of killing a white cop during a routine traffic stop must argue his own case in a predominantly white community determined to make an example of him.

Now you’re probably looking at this and saying, “Whoa Carson. That’s REALLY detailed.” That’s fine. Once you get your hotspots down, you do the same thing you do when you finish a script: YOU CUT. That means you make choices about which details are most important to convey your story. The idea is to consolidate five words into two here. Three words into one there. Try and make it snappier

This might leave you with…

A black law student accused of killing a white cop during a traffic stop must argue his own case in front of a white community determined to make an example of him.

This isn’t perfect. And the nature of logines is that you’ll keep fiddling with them until you get it right. But as you can see, we’re already in a much better place than we were with our original logline.

One final note. Every logline has a ceiling based on how good the concept is. Even the worst version of Jurassic Park’s logline is going to be better than the best version of Lady Bird’s. But if you have a strong main character and a compelling main conflict, you should be able to write a good logline. Just make sure you’re adding detail to those hotspots.

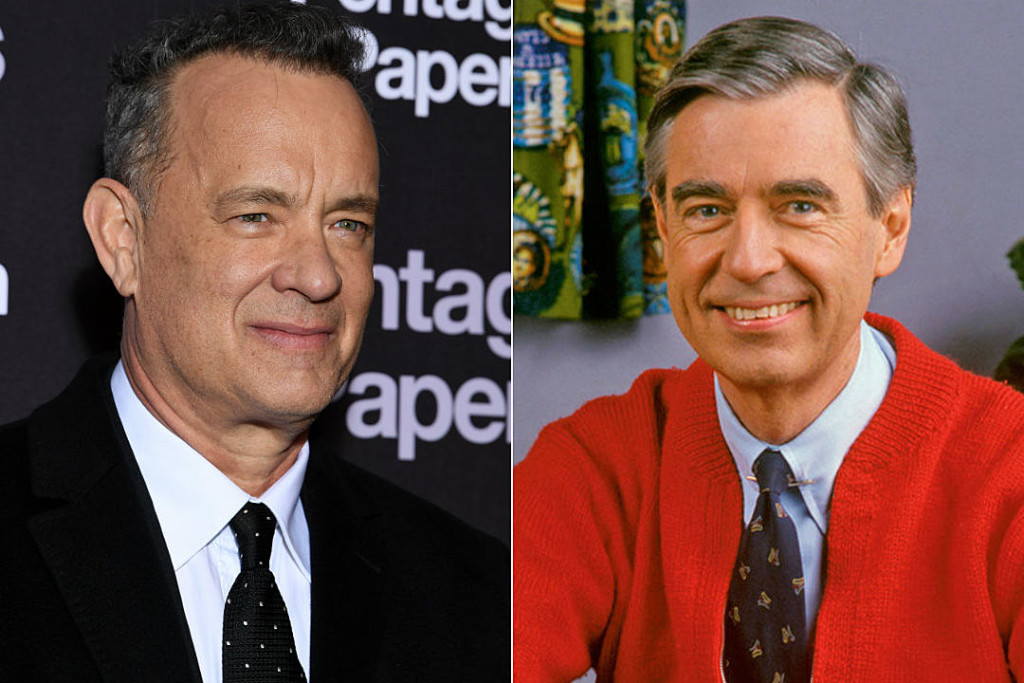

Genre: Drama/Biopic

Premise: A married news columnist who’s checked out of life finds his way back into it when he does a story on Mister Rogers.

About: Originally, this script made a prior Black List, I believe in 2012. Then last year it became a super-hot property, attaching Tom Hanks to play Mister Rogers. The writers, Micha Fitzerman-Blue and Noah Harpster, have used that momentum to secure a gig on one of next year’s big releases, Malificent 2. The two made their way up the ranks by writing on Amazon’s award-winning show, Transparent.

Writer: Micha Fitzerman-Blue & Noah Harpster (based on Tim Madigan’s memoir)

Details: 111 pages

I’ve avoided this script for so long. No matter how you presented it to me, there was no way I could conceive of a Mister Rogers movie being good. The character screams “boring subject matter.” And yet the project has received a ton of buzz. It didn’t make sense. Finally, my curiosity got the best of me. I am about to read a script about Mister Rogers. Wow. I hope I don’t fall asleep.

37 year old Tim Madigan has the perfect life. He just doesn’t know it. He has a beautiful caring wife in Catherine and a wonderful 3 year old son, Patrick. But he hates his life. He sleeps in a separate bed from Catherine. He avoids spending time with Patrick. Often times, he’ll come home after a long day of work and, as he’s about to pull into his driveway, keep driving and go to, of all places, Cracker Barrel. You know when you’re picking Cracker Barrel over anything it’s bad.

Tim works as a journalist, and because the film takes place right after the Columbine shootings, his boss wants him to write a story about what programs the shooters watched when they were children as a way to explore the connection between TV and violence. Ironically enough, one of the shows the kids watched was Mister Rogers. So Tim begrudgingly calls Mister Rogers to interview him.

When Tim visits the set in nearby Pittsburgh, the first thing he sees is Mister Rogers talking to a sick boy, trying to cheer him up. He looks around for the cameras, figuring this must be some Make-A-Wish Foundation deal, but is shocked to find that Mr. Rogers is doing this because he’s… well… a good guy. “He does this every day,” an A.D. tells Tim.

During lunch break, he attempts to get his quick and dirty interview in and then get the hell out of here, but is confused when Mr. Rogers starts asking him about his personal life and is genuinely concerned. When Tim gets home later, he starts looking up old Mr. Rogers interviews and becomes a bit infatuated with him.

Still, Tim is ready to move on from Mr. Rogers until, out of nowhere, his wife tells him he needs to leave. It’s not just that he’s mentally checked out on the marriage. It’s about Patrick, how he’s not at all a part of his son’s life. Devastated and confused, Tim moves into a hotel room, where he soon finds himself calling Mr. Rogers for advice. Slowly but surely, Tim sees what makes this man so amazing. He cares about people. And, more importantly, he cares about himself. He’s a friend to himself, something Tim has no context for.

Taking Mr. Rogers’ advice, Tim begins to work on connecting with people, starting with his co-workers. From there, he attempts to rekindle his relationship with his sick brother, whose business he ran out on years ago. The experience shows Tim what it means to be connected with others, which allows him to save his marriage. As the titles tell us at the end, Tim and Catherine are still married today and are the happiest couple they know.

The operating thesis when you write biopics about sugary sweet famous people is that you have to show their dark side. Expose to the world that they were battling a heroin habit or were terribly depressed. The reason you do this is to create contrast within the character. Because if the character is as friendly or amazing or honest as they presented themselves to the world… how interesting is that?

Over the years, I’ve grown tired of this approach. Partly because you know it’s coming. But also because it’s depressing. Sometimes you don’t want to look under the hood to see that the engine is fried. And it’s a big reason why biopics are broken. How many ways can we go inside a person’s life to find that while they were hugely successful they were also terribly miserable?

I didn’t think there was any way around that until today. These writers figured out a nifty loophole to the problem. What if you kept that famous figure just as sugary sweet as they’ve always been and shifted the fried engine over to a second character?

It’s genius, isn’t it? Mr. Rogers remains awesome in our heads. But we still get the conflict and obstacles and difficult journey that every story needs in order to be entertaining.

Everybody who’s considering a biopic should consider this approach. I’m not saying you should do it for sure. Every subject needs to be considered via its own strengths and weaknesses and then you pick the story that best accentuates the strengths. But with this genre getting so stale, you need to reinvent it if it’s going to stay interesting.

One of the reasons this story works so well is because the writers walk that line between Tim being a “bad” person but still getting us to root for him. Because when we meet Tim, he’s racing away from his wife. He won’t spend five minutes with his son. He ignores his coworkers. Let’s face it. He’s a selfish dick.

While some writers attempt to balance this out by writing a cliche “save the cat” scene, Fitzeraman-Blue and Harpster try something different.

There’s a moment early on where Tim is watching Mister Rogers do a segment for his show with puppets. And in the segment, a tiger puppet is asking another character if he, the tiger, is a “mistake.” And the other character is explaining to him that he’s not. But clearly Tim starts to see some of himself in that tiger and he breaks down. In that moment, we realize that Tim doesn’t want to be this way. He doesn’t want to be a jerk to his family. He just is. And he needs to learn how to change.

Once we know Tim wants to change, we root for him, regardless of what he’s done in the past. Had Tim been a jerk to his family and he doesn’t give a shit if he ever changes or not, there’s no way we’re rooting for him. That was a really clever solution by these writers to an age-old screenwriting problem.

My only issue with the script is that the narrative is sloppy. Mister Rogers is over in Pittsburgh, which is fine if you’re writing a memoir. Phone calls will do the job. But in a movie, we need to see people. We need to be around them for the most impact. So there’s a lot of driving back and forth to Pittsburgh that messes with the pacing.

On top of that, Tim’s brother’s sickness isn’t woven into the first half of the story enough. As a result, when it becomes the primary storyline in the last 40 pages, it takes us awhile to adjust. And, again, it’s because everyone is so far away from each other. Tim’s in one city. Mr. Rodgers is in another. Tim’s brother is in a third city. It was Iike Avengers-level exposition needed to keep track of all these places.

This is why most screenplay-friendly stories take place in one area with one set of characters that are easily accessible. So you don’t need to spend 25% off your script muscling through the exposition required to keep the story clear.

Despite that, this was a really enjoyable read. Is it a little too sweet in places? Sure. But come on. We’re talking about Mr. Rogers here. If you can’t feel good after a movie about Mr. Rogers, when can you?

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[x] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: I want to make it clear that I loved this script. But this lesson is still relevant for amateur screenwriters – When considering a script, you should consider the amount of exposition that will be required to tell the story. If you have a lot of characters moving around to a lot of different places (like Avengers or here), you’re going to need a lot of scenes that remind the audience where we are and explain to them why we’re going to the next place. There are things you can do to make these exposition-heavy scenes more palatable, but sometimes the best solution is to write a simpler “spec-friendly” story where you don’t have to worry about exposition in the first place.

Genre: Super-Hero

Premise: In order to fulfill his destiny of “freeing” the universe, an evil planet-hopping alien must defeat the largest group of superheroes ever assembled.

About: The most anticipated movie of the year is upon us. Avengers: Infinity War baby!

Writers: Christopher Markus & Stephen McFeely (based on comics by Stan Lee and Jack Kirby) (additional characters by Joe Simon, Steve Englehart, Steve Gan, Bill Mantio, Keith Giffen, Jim Starlin, Larry Lieber, and Don Heck)

Details: 2 hours and 30 minutes

(MAJOR MAJOR MAJOR SPOILERS EVERYWHERE!!!)

Avengers: Infinity War contains writing challenges that no other writer in the history of cinema has had to face. Watching the writers try to navigate these challenges was almost as fun as watching the show-stopping set-pieces. I want to jump right into the analysis but maybe we should do a quick breakdown of the plot first.

We’ll start with Thanos. Thanos is a big purple alien who wants to destroy half the universe in order to take care of its overpopulation problem (don’t worry, we’ll get to that). In order to achieve this, he must collect six “infinity stones” and place them in his giant infinity stone glove.

Without getting into detail, the relevant stones are located inside two of our featured superheroes. The first is Vision, aka Boring Maroon Guy, and the second is Dr. Strange, who’s got a stone tucked inside his necklace. After Thanos gets the other stones, he must face these two heroes, along with each of their mini-posses.

There’s a lot that goes on in the meantime. Iron Man, Doctor Strange, Spider-Man and Peter Quill take the fight directly to Thanos on Thanos’s old planet. Captain America, Black Panther, Black Widow and David Banner (Hulk) go to Wakanda to stop Thanos’s Death Team from stealing Vision’s infinity stone. And Thor, Rocket Raccoon, and Groot go back to Thor’s home world to try and build a new hammer.

In the end, none of it matters, because Thanos succeeds! Once he’s got the stones, he snaps his fingers, and half of every being in the universe turns to dust, including crowd-favorites Spider-Man and Black Panther! But don’t these two have sequels coming out in the future? Have those sequels now been canceled? We’ll have to wait until Infinity War Part 2 to find out.

Yowzers, where do I begin with this?

The first thing that struck me was how the writers decided to unify the narrative. Like I said, no writers have been asked to keep track of this many characters before on this scale. That’s because doing so is hard. If you want to see how hard, watch any of the recent Transformers or Pirates sequels. Note how sloppy those narrative are. When bad writers are tasked with jumping around to a ton of different story threads? It becomes disaster sauce quickly.

So Markus and McFeely cleverly wrapped the narrative around Thanos’s pursuit of his goal. Which makes sense. He’s driving the action. He’s the one with the big plan. Everyone else is reacting to it. So why not make him the centerpiece of the story? That way whenever stuff gets too complicated, we can cut back to Thanos and instantly remember, “Oh yeah – this is what this is all about. The guy getting the infinity stones.” It’s almost as if Thanos is given a traditional Hero’s Journey, despite the fact that he’s not the hero. That’s a major reason why people are coming out of this movie feeling like Thanos is Marvel’s best villain ever.

What’s so surprising about this working is that Thanos’s plan, unless you’re under the age of 13, is the silliest plan ever. He wants to eliminate half of the universe because there are too many… beings in it? Uhhhh… okay.

Marvel, of course, is directly responsible for how silly this plot is. They made the fate of earth the stakes in the first Avengers. The galaxy is at stake in the second Guardians. That makes both of those stakes too small for this movie. Which is why they needed to take things all the way to the universe level.

But there’s a problem with that. If Thanos destroys the entire universe, he’s dead too. This is what necessitated this silly compromise of HALF the universe. Of course, now you have to come up with a reason why someone would only want to destroy half the universe. And the best they could come up was this idea of overpopulation, which makes absolutely zero sense.

But I’ll give it to these guys. It worked. And it worked mainly because Thanos was such a strong villain. You believed him, even if you didn’t necessarily believe what was coming out of his mouth.

Markus and McFeely weren’t bulletproof though. Getting all these characters into the places they needed to be to get the story moving took a ton of exposition – and in my humble opinion, more than what was needed. For a good hour there, it felt like every scene was a group of people in a room, talking about where they needed to go and why. Or why something from the past was relevant to what they needed to do in the present. That Guardians Thor sequence in the Guardians ship was yap yap yap yap yap yap yap yap yap. It could’ve been cut in half.

A lot of people are praising the humor in this film. What may surprise you is that the humor wasn’t being used to entertain you. It was being used to distract you from how mind-numbingly dull these exposition scenes were.

But for the most part, the screenwriting was strong. I loved how the movie started, for example. Note how we don’t start IN THE BATTLE. We started AFTER THE BATTLE. They always say, “Come into the story as late as possible” or “Come into the scene as late as possible.” They knew that Thanos killing an army of people we didn’t know or care about would’ve been a visually exciting but emotionally vacant experience. So we enter in the aftermath. An inexperienced screenwriter would’ve botched that. “We’ve gotta show the battle first! It’s a comic book movie! We need as much action as possible!” Not if it’s unnecessary you don’t.

Markus and McFeely also knew they had to demonstrate right away that Thanos was the ultimate badass, someone even 30 superheroes would have a tough time taking down. So they have him casually beating up, of all heroes, the Hulk. Once we see that, we’re like, “Oh, okay. The Avengers are f%$#d.”

Oh, and one of the reasons Thanos comes out of this such a star? Is that they do something I constantly tell writers to do with their villains. They go AGAINST THE OBVIOUS. Thanos isn’t some over-the-top asshole who enjoys killing people because HE’S A VILLAIN and THAT’S WHAT VILLAINS LOVE TO DO. He’s quiet. He’s rational. He’s almost sad. It goes against every stereotype you think of when you think of a movie villain. Which is exactly why he stands out.

Then there were very specific things I liked. One of the most frustrating things about screenwriting is the troubleshooting. You’re constantly running up against annoying problems you have to solve. Take, for example, the Hulk. Clearly, they’re saving Hulk for Part 2. They knew that if Hulk is running around beating up bad guys willy-nilly in this, he loses his luster in the second half of the 2-film arc. The problem with that is, without the Hulk, Bruce Banner is useless. So the writers were saddled with either figuring out how to make him NOT USELESS, or throwing him up in one of those ubiquitous control rooms and having him say things like, “We’ve got incoming in Vector A!”

The idea to put him in Iron’s Man’s “Hulk Buster” suit was a really clever solution to this. This way, you get Bruce Banner out on the battlefield fighting with the others where he’s still kind of able to be the Hulk.

Okay, enough screenwriting. It’s time to be a geek and get into my raw thoughts, starting with Loki. THAAAAAAANNNNNNNK YOUUUUUUUUUU. What a lame character. Maybe my least favorite character in all of Marvel. I’ve never seen a franchise try and push a character so much who clearly wasn’t working. NOTHING about this character worked. The costume and make-up were off. The hair was a major fail. The overtly manufactured broken relationship with his brother was a fail. His motivation was never clear. Just an awful character all around. Thank you for killing him, Marvel. May he never resurface.

I thought the Nebulus Bebulus guy who looked like a character out of Harry Potter was AWESOME. That early fight with him against Iron Man and Dr. Strange was badass. I loved how he just stood there, unmoving, while cars split in half around him.

I was surprised by what they did with Dr. Strange. First of all, I didn’t know he was so powerful. I thought he was only able to do a few time-slowing Matrix moves. But he’s full-on badass here. I mean, at times, I thought he might be the most powerful Avenger of all.

I love Spider-Man. They nailed that casting with Tom Holland. It almost makes it obvious how badly they botched the casting the last time around. I loved the new suit Iron Man gave him. I love how he’s basically mini-Iron Man. I love how he calls Iron Man, “Mr. Stark.” Their chemistry is amazing. It made me want them to have their own movie together.

And I was pissed there weren’t more surprises. I thought that’s what comics were known for – these big shock moments. I was hoping to see Silver Surfer or Captain Marvel. Instead the big surprise was… Red Skull?? First of all, I don’t even know who Red Skull is. But he’s lame as shit. There was lots of murmuring in my crowd when he arrived, but my groan cut through all of it. What a dumb ass character. They should’ve given us someone actually cool. Very disappointed on the cameo front.

Speaking of disappointment, I didn’t love the ending. Not just because of the obvious things (oh yeah, right, Black Panther is dead, sure). But because it was confusing. I thought this whole “destroy half the universe” thing was going to result in, you know, DESTROYING HALF OF THE UNIVERSE! When people started fading into dust, my first thought was, “Oh, they’re being transported to another dimension or something.” It didn’t occur to me that THIS was how half of the universe was destroyed. Major lack of clarity there. Big screenwriting mistake. Because think about it. Everyone knows Spider-Man has a movie coming out next year. He’s not dead. So of course I’m going to think he was being transported somewhere. But I guess, according to these writers, that means he’s “dead.” I don’t know. It was stupid. And I get why they did it. They needed some big suspenseful conclusion to make you want to come back for part 2. But we needed a visual with more FORCE and way more CLARITY. This was a big movie fail.

Okay, finally, for no reason other than why not. Here are my favorite Avengers characters ranked from best to worst!

1) Iron Man (RDJ owns this character as well as Harrison Ford owns Indy)

2) Spider-Man (brilliant casting)

3) Ant-Man (furious he wasn’t in this)

4) Thor (what a comeback for this character from his first films)

5) Starlord (funniest of everyone but Thor giving him a run for his money)

6) Groot (shortchanged here but still awesome)

7) Dr. Strange (moved up the ladder of awesomeness with this film)

8) Bruce Banner (the Hulk still rocks)

9) Captain America (slightly annoying, but still a badass)

10) Rocket Raccoon (also known as “rabbit”)

11) Drax (hilarious)

12) Black Panther (I still think this guy’s boring but his suit makes up for it)

13) Scarlet Witch (dropping the accent pulled her up from being the worst Avenger ever)

14) Black Widow (I mean, I guess)

15) War Machine (still not really sure why this character exists)

16) Falcon (forgettable but at least he’s not annoying)

17) Hawkeye (I can shoot arrows!)

18) Bucky (a guy whose power is an arm. Sure, why not)

19) Gamora (so glad she died. What a lame character)

20) Vision (most boring superhero ever possibly?)

[ ] What the hell did I just watch?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[xx] worth the price of admission

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: This is the first time I think I’ve ever seen a villain be given the Hero’s Journey. I definitely didn’t think you could do that. I’m still trying to figure out if this is something that only works inside this unique situational universe or if it could be used in other genres. That would be a neat new screenwriting power to play with if that were the case.

Genre: Thriller

Premise: Facing the prospect of permanently losing her hearing, a music teacher gets an artificially intelligent cochlear implant that convinces her to commit mass murder.

About: What would you do if the only thing that gave you meaning in this world was to be taken away forever? — If there was an experimental procedure, with untold risks, that could prevent that scenario, would you undertake it? — Murder In Grave is a slow burn thriller, that has been crafted with the sole purpose of emotionally strangling the main character from page one until fade out. A hurdles race where the obstacles get higher and faster the further you go on. — Naturally, as the stakes increase, something always has to give.

Writer: Branko Maksic

Details: 97 pages

It’s been a rough stretch on the site the last couple of weeks as I’ve been handing out “wasn’t for mes” like Kanye MAGA tweets. I’ve actually started to wonder if I’m the problem. Have I read so much that nothing excites me anymore?

Uhhhh… NO!

Tie a cinder block to that hypothesis and throw it in the Mississippi River. I actually don’t need that much from a story to enjoy it. I don’t need major twists. I don’t need subject matter I’ve never seen before. I just need characters who are compelling and feel truthful, and a simple story told well.

Are you hearing me!?

No?

Maybe you need to check your hearing then. :)

Former FBI agent Deborah Holian was at the Oklahoma City Federal Building on that fateful day in 1995 when it blew up. She survived, but lost 90% of her hearing. Due to the power of technology, however, she now wears hearing aids that are so good, she can teach her second love, music.

Unfortunately, Deborah receives the bad news that that final 10% of her hearing is about to go. And when that happens, hearing aids won’t be able to help. But the doctor suggests an alternative. A beta program that requires doctors to fuse an advanced form of “artificially intelligent” hearing aids directly to the brain. If it works, she’ll be able to hear like normal people again.

Deborah goes for it, and is initially thrilled with the results. She can hear her husband, Gene, again. She can hear her son, Jacob, who’s just about to have a baby with his wife. It’s all good under the hood.

That is until Hank arrives. “Hank” is the voice that appears inside of the high-tech hearing aids and starts talking to Deborah. Hank is an asshole. He wants Deborah to do things for him, the first of which is to go to Home Depot. When Deborah refuses, she gets a call from Jacob that his newborn son is missing!

Now that Hank has Deborah’s attention, he says if she wants to see her grandson again, she’ll make that Home Depot run. Long story short, Hank gets Deborah to build a few bombs and plant them at a local park during a busy day. The bombs blow up and a lot of people are killed.

Because Hank is an asshole, he kills the baby as well, and then Gene. By this point, Deborah realizes that Hank is a real person and vows to find him and kill him. But she fails. Hank and his crew of hearing aid avengers kill her instead. The End.

At the risk of sounding like a broken record, Murder in Grave was yet another script where I had a tough time buying into the concept. From the idea that the hearing aids were artificially intelligent to a disembodied voice being able to order our hero around. It’s not the most unbelievable premise I’ve come across. But there was a casualness to the execution that had me constantly skeptical that any of what I was reading would go down in real life.

Branko’s choice of making Hank a grade-A asshole from the start (his first line is “Wake up, Deborah… I said wake up you fucking cunt.”) was the wrong one. It would’ve been way more interesting if Hank had to first earn Deborah’s trust. Start him off being nice and slowly manipulating her over time, until he eventually became the asshole. The choice to make him a dick from minute 1 to minute 90 made him on-the-nose, unbelievable, and uninteresting.

The script also had a bunch of singular issues that, on their own, weren’t script killers, but when you added them all up, made script death inevitable. Take for instance the opening. Having our hero lose her hearing in the Oklahoma City Federal Building bombing was way over-the-top. And it had nothing to do with the rest of the story.

Writers often think they need HUGE REASONS for everything because THIS IS A MOVIE and BIG THINGS HAPPEN IN MOVIES. And while there are certain situations where that makes sense, most of the time something simple will do. We’re talking about hearing loss here. It could’ve been dealt with genetically.

The only relevant-to-the-story information that comes out of that opening is that our hero was an FBI agent. But not only does it take half the script for us to learn this (she’s described in the opening only as a “woman”), but her being an FBI agent has zero effect on the story other than it kinda gives her a little more knowledge of how to investigate where Hank is in those final 20 pages.

If you’re going to assign big labels to your character, those labels need to pay off in a big way. An FBI agent implies a lot to the reader. So to throw that out there and then barely use it is either confusing or sloppy.

Then there were very suspect choices such as killing a baby. Baby-killing is not encouraged. It did work in Thelma, one of my favorite movies of the year, but that death was so carefully set up throughout the screenplay that it made sense when it finally happened. Here, it just seems like we’re killing babies for shock value.

After the dead baby, our main character goes off to get revenge and… fails? They kill her? It was at this point where my head dropped and I just started shaking it. I mean, you already killed a baby. Now you’re not even going to allow the audience the satisfaction of having our hero kill the person who killed the baby?

Even besides that, this is a silly fun genre premise. You don’t kill the main character at the end of a silly premise. You’re not making Braveheart here. You’re making a movie where artificially intelligent hearing aids tell people to kill. At the end of these movies, your hero wins.

There’s actually a great example of this argument during the recent Rampage press tour. The Rock’s character originally died at the end of that script. When The Rock read it and found that out, he told the filmmakers, “If my character dies, I’m not doing this movie.” And the writers and director actually tried to convince him that it was the right choice. He finally shot back an answer that, sadly, showed that The Rock knew more about screenwriting than the professional writers working on that movie: “There’s a crocodile the size of a football stadium in this movie. We’re not making Saving Private Ryan.”

Anyway, this is a tough review to give because there isn’t any one fix that I can point to here for Branko. It’s more of a tonal thing and learning how to make choices that are more organic to the story you’re telling. Hopefully me highlighting some of these choices helps.

Curious to know what you guys think.

Script link: Murder In Grave

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: When constructing characters, consider not only where they start, but where they end. If they start as a crazy weird motherfucker and end as a crazy weird motherfucker, that character probably isn’t going to be interesting. That was my issue with Hank. He starts off as a raging asshole and he never changes. Had he started in a nicer (albeit still manipulative) place and then gradually became a raging asshole, now you have a more dynamic character. This is not the case for every character, guys. And the smaller the character, the less you need to worry about this tip. But you should definitely consider it for all of your big characters.