Search Results for: 10 tips from

A couple of weeks ago Sean O’Keefe sold his pitch, Riders On The Storm, to Fox for half a million dollars. The script is about a heist crew that pulls off sophisticated robberies during severe storms. I realized we don’t talk about pitching very much on the site, even though it’s a huge part of the business. Oftentimes, after you meet someone about your script, you’ll pitch them other projects you’re working on. So I thought Sean would be the perfect person to ask, “What’s this pitching thing all about?” Sean is also currently writing a film adaptation of “Apaches” for producer Jerry Bruckheimer and Disney Pictures about the NYPD along with writing partner Will Staples. Enjoy the interview.

SS: Can you tell us how you got started in screenwriting? What was your background leading up to it? Did you do anything else film-related?

SO: I grew up between two isolated worlds – a cabin in Alaska with no running water and a draconian boarding school in England. As a result movies for me were always a way of feeling connected with the outside world. My final semester in college, I decided to write a spec based on Milton’s “Paradise Lost” and some family friends hooked me up with a meeting with veteran screenwriter Jay Cocks who had worked with Scorsese on “The Age of Innocence.” Jay told me I was crazy – Hollywood would never make it – so I let the idea go. Now, of course, Alex Proyas is making a film based on the material. It’s the same lessen I’ve learned a hundred times: follow your gut no matter what because it’s all you have.

After paralegalling in New York my first year out of school and writing two painfully bad scripts on my lunch breaks, I moved out to LA and worked in development first for Neal Moritz at Original Film then Michael Ovitz at APG, the film production arm of AMG. I then co-founded a film and video game production company called Union Entertainment with Rich Leibowitz.

Around that time, my father passed away and I spent a week in ICU waiting for the inevitable to happen. It turned out to be a period of reckoning for me. I realized you only have so much time to do what you want in life, so I made the choice to return to screenwriting.

SS: When was the first time you got paid to write? How many scripts had you written before you got that first paycheck?

SO: The first time I got paid was in 2003 with my former writing partner, Will Staples. We had gone out with a Mayan period piece spec (my fifth script at that point) that didn’t sell but was well received for the writing and two weeks later Sony called up and asked if we wanted to write King Tut for Roland Emmerich. We came up with a take, Roland and the studio liked it, and the rest is ancient history…

SS: I’ll be murdered if I don’t ask this question. But how did you get your agent?

SO: I was lucky in that in my capacity as a producer and exec I had dealt directly with a number of agents and managers around town. My agent, Nicole Clemens at ICM, and my manager, Brian Lutz, were both reps who were excellent at representing their clients when I was on the other side of the table. When it came time for me to devote myself to writing again, they were the first people I reached out to.

SS: In your opinion, what’s the most difficult thing about screenwriting, and what’s the best way to tackle that difficulty?

SO: Knowing that I am writing for an audience is the hardest aspect of the process for me. The moment I look up from the page and see the faces in the proverbial crowd – studio execs, agents, managers, other writers – I feel stage fright setting in. I start to second guess myself. I wonder if I have the right character for my story or the wrong story for my character. I fall into the trap of perfectionism. The trick is to write as if you are writing purely for yourself, but it’s easier said than done. Oddly, Donald Rumsfeld had some wisdom in this arena: “You go to war with the army you have, not the army you might want.” Eventually, you have to stop second guessing yourself and charge into battle.

SS: You’ve obviously been out there, talked to producers, have a beat on their needs. What do producers want these days? Are there some common genres they’re asking for? Do they want the “Next Twilight?” The “Next found footage” script? What are you hearing?

SO: Everybody thinks they want the thing that just performed at the box office but the truth is that they want the next great idea that walks through the door. Your job is to bring them that next great idea. I’ve never been very good at forecasting what the market wants and then tailoring my output accordingly. I run with the movie I most want to write and hope that others feel as excited about it as I do…

Disappointment, however, lurks around every corner in this process. That is why I have a personal rule of thumb, which is my ‘one in ten’ rule. That is for every ten swings at bat you connect with one ball. For every ten meetings or reads, someone connects with what you are trying to do. It’s fuzzy math, but it helps to keep your expectations in check. Not everyone is going to resonate with what you’re doing. But that’s okay – you only need one in ten to actually make real progress. Every studio passed on our Mayan epic, but one liked the writing enough to call us back in. That one call gave birth to our career.

SS: We were having this debate the other day on the site. Should an unknown writer try to break in with something heartfelt and personal to them – something that will bring out their best writing? Or should they write something high concept and marketable, even though they won’t be as emotionally attached to the writing?

SO: Stick with the cliché of writing what’s in your heart. It’s a cliché for a reason. But if it’s a big summer action movie that’s in your heart, then consider yourself lucky.

SS: If you could go back in time and give your younger screenwriter self some advice on how to get to the professional level faster, what would you tell him?

SO: Four things…

Write as much as you can. It’s all about clocking the hours and getting words on the page. In the Gladwellian sense you need to get in your 10,000 hours, so the sooner the better.

Write, rewrite, then move on. Don’t get stuck trying to overly perfect a script in the beginning. You will learn more from cracking a new story than you will from debating where to place your commas.

Avoid the Freshman Writer Trap. The problem is that in the beginning many new writers think they’re the next Robert Towne – and perhaps they will turn out to be – but it will likely take years to know. Don’t assume that you shit gold from the get-go. The likelihood is that your first few scripts will be abominations in hindsight (at least mine were). Humility will keep you open to constructive criticism and ensure that you are learning and progressing.

Run your writing career like a producer. Have a slate of projects – one or two that you are focused on at any point in time and the others that you continue to inch forward as the opportunity arises. Never have just one baby. This is Hollywood. There is no safety net. You need to have a Third World family of projects because sadly not all of them are going to survive.

SS: What is a pitch meeting and how does one go about getting one? Does an agent read your latest script and ask you to come in? Is it something your agent works to set up? Is it you having a previous relationship with the producers and saying, “Hey, I got this new idea I want to come in and pitch you?” How does a writer get one of these things!?

A pitch is a meeting where you make a verbal presentation of a story that you want to sell so that you can be paid in advance to write it as a script.

The three essential ingredients to a pitch are having a sample script that people already like, a story to pitch, and an agent to set the meetings.

Pitches can arise in two basic ways. First, you tell your agent you have a pitch you want to take out to the town and they set meetings with producers who then take it into studios where they have their strongest relationships. Second, a producer brings you an idea and you take it out to the town exclusively with them attached.

SS: With your recent pitch sale, were you going in to specifically pitch them this project – with both sides already knowing what you were going to pitch them? Or was it something that emerged during the course of the meeting?

SO: The pitch meetings were specific to this project, which is the way it typically goes down, but there are exceptions. For example, on “World’s Most Wanted,” a spy thriller we set up at Universal, the original pitch was about a Mexican drug cartel but the exec didn’t respond to the subject matter. He did, however, like the team-versus-team dynamic of the story and said if we could come with a new subject, he would be interested. So we did several weeks of research and found a real-life NATO team that hunts the world’s most wanted criminals. We went back in, employing a similar story with the new subject, and he bought it. It was proof that you can never tell which direction a project is going to break, but you’ll never know unless you try.

SS: Can you tell us how a pitch that leads to a sale works? Are they all different? Do they tell you right there in the room “yes, we’re buying this?” Or does it happen afterwards, once they’ve checked with their superiors?

SO: I dream of the ‘in room’ sale, and I know it has happened to others, but I haven’t been the recipient of that kind of spontaneous largesse yet. For me, selling a pitch has always entailed an agonizing wait – sometimes a few hours, sometimes a few days. Now that the studios have more leverage and they are more picky about what they buy than when I started in the business, they aren’t in the same real-time rush to respond that they used to be back in the glory days of the mid-90s spec market when high concept ideas with poor execution seemed to sell on almost a daily basis. Now execs seem more afraid of being left holding the bag on a project than they do being left out of a sale.

The truth is that very few people at the studio have the authority to buy a pitch without running it up someone else’s flagpole first. If you happen to be in the room with someone who can say ‘yes’ then you’re already doing something very right – in which case keep it up!

SS: People talk about different kinds of pitches. There’s the 5 minute pitch. The 10 minute pitch. And like the longer 20 minute pitch where you pitch the whole movie. I can’t imagine a busy producer able to concentrate for 20 minutes on any writer. Do you follow this formal time-specific pitch list or do you just do it your own way?

SO: I think it depends on where you are in your career as a writer and what the nature of the pitch is – i.e. are you pitching on a rewrite the studio has submitted to you, or are you pitching an original of your own. If it’s a rewrite, and your stock is high with the studio, you can get away with a more limited pitch – i.e. “Here are the three major problems with the existing script and here’s how I would address them.” Your presentation will then likely lead into a more informal conversation with the exec.

However, if it’s an original then your choice is more problematic and the decision to go long or brief depends on a number of factors… How established are you (i.e. how much does the studio already want to be in business with you)? If you are one of the lucky few hot scribes around town then you can probably get away with the ‘less is more’ approach. If not, you might want to incorporate more detail in your presentation. The risk is that you will lose the exec’s attention and give them more to pass on, but the upside is that if you do manage to hold their attention you want them to know that you have this story worked out in enough detail that you feel confident writing it.

Another factor to consider is what kind of story it is. If it’s a rom-com in a familiar setting like a wedding then you probably don’t need to sweat establishing the world in great detail. But if you’re pitching a sci-fi or action film that takes place in an original or arcane world, then you probably want to lead with an explanation of the setting of the story so the exec can better visualize what you are talking about and understand the consequences of your dramatic choices based on the rules of the universe you are drawing from.

However…if I had a gun to my head and had to give you an ideal pitch length, I would say 12 minutes. Beyond that any exec is bound to start wondering whether they’re going to have sashimi or the dragon roll for lunch.

SS: Can you give us any tips for nailing a pitch? It’s such a different art form from writing itself. What do you think the key is?

SO: You have to know your strengths and play to them, and by that same token know your weaknesses and try to avoid them or compensate for them. If you’re good with banter, then reduce the length of your pitch and put more weight on the Q&A with the exec where you respond to their questions and observations on the fly. If you feel more confident memorizing your pitch word for word and creating a more airtight presentation, then go for that. It’s a personal choice. No one size fits all.

In addition, try to get into the pitch itself as quickly as you can. Most execs are busy and under a lot of pressure. They’re only going to be able to listen to so much of you talk, no matter how enthralling you are. Dedicate as many words as you can in the meeting to your story, not how awesome your Cabo bachelor party was or that you just hit level 85 in World of Warcraft.

Lastly, make it personal. You’re trying to convince your audience that you have this story inside of you – that you’re going to burst if you don’t get it out, and that you’re the one person who can tell it. You have to walk into the pitch believing that you’re entering with a briefcase full of diamonds and that they’d be crazy to let you walk out with it. Only never carry a briefcase into a pitch…

So I’m sitting there reading Sex Tape last week and it hits me. Even the high level professionals getting a million bucks a script struggle with their second acts. And then I really start thinking about it (always a bad thing), and it clocks me. Not only do they struggle with it. They FAKE IT. No seriously, they do. They don’t know how to get through their second act so they throw up a bunch of smokescreens and set pieces and twists and turns, all in the hopes that you won’t figure out that they have no idea what they’re doing. And hey, who can blame them? It really is a fucked up act. I mean the first act is easy. You set up your story. The last act is simple. You conclude your story. But if you’re not setting up and you’re not concluding, what the hell are you doing? And why does the most confusing act have to be twice as long as the other two? Well, I’m going to answer that for you. It’s time to figure out the dreaded SECOND ACT.

UNLESS YOUR MAIN CHARACTER HAS A GOAL, YOU WILL ALWAYS STRUGGLE WITH YOUR SECOND ACT

This is technically a pre-second act tip, but it’s such an important one, it’s worth noting. Your main character needs something he’s after (a goal). The reason for this is, much of the second act will be dedicated to your character’s pursuit of this goal. So if there’s no goal, there’s nothing for your character to do. There are exceptions to this rule just like there are exceptions to everything (The Shawshank Redemption and Lost In Translation do not follow this format). But for the most part, if you want to conquer your second act, giving your hero a clear goal is essential.

A MAJOR CHARACTER THAT’S BEING TESTED

Okay, here’s why most second acts fail: Because writers don’t realize the second act is about CHARACTER DEVELOPMENT. That’s not to say there isn’t action in your second act. Or plot. Or thrills. Or horror. There can be all these things. But the bigger overarching purpose of the second act is to explore your characters. Once you realize that, you’re way ahead of everyone else. All of this starts with your character’s defining flaw – or “fatal flaw” – which is loosely defined as the thing that’s held your character back his/her entire life. Once you identify that flaw, you’ll create a journey to specifically test it over and over again. These tests will force your character to grow, which will in turn bring us closer to your character. So in The Matrix, Neo’s fatal flaw is that he doesn’t believe in himself. Therefore many of the scenes in the second act are geared towards testing that problem. The building jump. The dojo fight. The Oracle visit. The Subway fight. Each time, that lack of belief is being tested. And each time, he comes a little closer to believing. Now, note how I didn’t say it had to be your hero who had the flaw. Many times it’s a secondary character who does the changing in a story. So if you look at a movie like Star Wars, Han’s flaw is that he’s too selfish. That flaw is tested when he and Obi-Wan get in arguments, when he’s given the chance to save the princess, and when he’s given a chance to join the Death Star battle. Or Cameron in Ferris Bueller’s Day Off. His flaw is that he doesn’t take chances in life. Virtually every scene in the movie is Cameron being given a chance to let loose, to “enjoy life.” Personally, for me, I think the best stories are when everybody goes through some sort of change. So make sure that your second act contains a healthy dose of character exploration.

MORE CHARACTER EXPLORATION – RELATIONSHIPS

Relationships are the other main way you’re going to explore character in your second act. Long story short, you’d like to have two or three unresolved relationships in your movie, and you want to use your second act to resolve them. Much like the character flaw I mentioned above, there’s usually a key issue in every relationship that needs to be fixed. Many of your scenes in the second act will be used to explore that issue. In Good Will Hunting, the three biggest relationships are Will and Sean, Will and Skylar, and Will and Professor Lambeau. Each relationship needs to be resolved. The key issue with Will and Sean is opening up. The key issue with Will and Skylar is fear of commitment. And the key issue with Will and Professor Lambeau is what to do with Will’s talent. In the second act, Good Will Hunting jumps back and forth between these relationships, continually hitting on these issues, pushing each of them to the breaking point. Now of course, how much time you spend on this will have a lot to do with the kind of movie you’re writing. Good Will Hunting is an unapologetic character piece. But I’m not sure I’d recommend intimately dissecting three separate relationships in a movie like 2012 or Taken. But that doesn’t mean you should abandon the practice altogether. Maybe you cut down the number of relationships explored. Maybe you cut down the depth or the time used to explore those relationships. But you should probably have at least two relationships you’re exploring in your second act.

THE MIDPOINT STRIKE

One of the problems with second acts is that they go on FOREVER! 30 pages longer than the first and third acts. No wonder they’re so damn cryptic. But you have a secret weapon at your disposal to fend off this pit of boringness: the MIDPOINT STRIKE! Please don’t go around using this term. I just made it up for this article. The midpoint is that point in the story where the audience is sort of used to what’s going on, and is starting to feel like they have a handle on things, and are therefore on the verge of getting bored. By WHACKING them with the midpoint strike, you can change all that. So in Star Wars, it’s when they get to Alderran and the planet has been destroyed! In Jerry McGuire, it’s when Sugar steals Cush away from Jerry at the draft. In Psycho, it’s when Norman has killed and disposed of Marion Crane’s body. In Avatar, it’s when they destroy Home Tree. You need something to JOLT the story onto a different path. If you don’t, the script gets too predictable. You have a lot of options with what to do with the midpoint strike. It can be plot based, character based, internal, external, a big twist, the death of a character. Anything that changes the game a little bit. So in Source Code, it’s when Coulter finds out that he’s dead (character based). Or in Star Trek (2009), it’s when they realize Nero is going to destroy Earth and they have to either rendezvous with the rest of the star fleet or take a chance and stop him on their own (plot based). You get bonus points if your Midpoint Strike ups the stakes. So in Star Trek, earth potentially being destroyed is a pretty big upping of the stakes, wouldn’t you say?

THE BUILD (AND THE POWER OF OBSTACLES)

Here’s something I don’t think enough writers realize. A second act should BUILD. There should be peaks and valleys, sure. But overall, the audience should feel like we’re BUILDING towards something. In most screenplays I read, the second act does the opposite. It peters out. It sputters to the finish line. So how do you avoid this? By placing obstacles in front of your character’s goal, and by making each obstacle bigger and more difficult than the previous one. Here’s an analogy. Think of a video game. In most video games, the goal is to get to the final level and defeat the boss. Each level before that, then, is an “obstacle” to achieving that goal. And each level, in order to make getting to and defeating that boss harder, is more difficult than the previous. So if you look at Raiders Of The Lost Ark, all Indiana has to do at first is get to Cairo, walk around in a half-disguise, and look for the Ark. His obstacle is not getting caught. Pretty simple. But then he gets caught and buried in a cave. Now he has to get out. A slightly bigger obstacle. Then he gets out and has to destroy a plane and a bunch of Nazis. Bigger obstacle. Then he has to catch up with the caravan carrying the Ark and stop them. Bigger obstacle. Since each obstacle is more difficult, we get the sense that we’re BUILDING towards something. Now the truth is, this is an imperfect science, because sometimes you need to give your characters a breather, and you do that by throwing in a smaller obstacle. For example, while Luke and Han gunning down Tie-Fighters in the Millennium Falcon was a big obstacle, I wouldn’t say it was bigger than escaping the Death Star. Still, on the whole, your main obstacles should continue to get bigger and more imposing. This is what will create that necessary BUILD that makes a second act fun to watch.

BUILD BUILD – EVERYWHERE BUILDING!

Take note, the build is not relegated to the plot. It should be incorporated into your character’s fatal flaw and those unresolved relationships as well. That way, the story is building ON EVERY FRONT! For example, in Back To The Future, George McFly’s fatal flaw is his lack of belief in himself (hey, kinda like Neo). At first this flaw is tested when Marty introduces him to Lorraine at school. She’s more interested in Marty though, and George slinks away. Nothing is lost because she barely paid attention to George in the first place. Next, he asks her out at the diner. This time, there’s more on the line because he’s all alone and putting himself out there. In the end, of course, he’s gotta take down Biff AND ask Lorraine to the dance, the ultimate test of whether he finally believes in himself. We get that building sensation because each test had more at stake than the previous one. — Now on the “unresolved relationship” front, let’s look at one of the greatest rom-coms of all time, When Harry Met Sally. Their unresolved issue is trying to remain friends. At first they don’t really like each other so it doesn’t matter. But then they start hanging out, making that pact more difficult. Then they start dating other people, making it even more difficult. Then they start getting into serious relationships, making it even MORE difficult. So the act of trying to remain friends becomes more and more challenging by building the obstacles in front of that goal. As long as all the elements in your second act – plot, fatal flaw, relationships – are BUILDING towards a conclusion, you’re in good shape.

THE FALL

The end of your second act is when your character has tried everything. He’s overcome all the previous obstacles. He’s managed to keep his relationships together. He may even believe he’s overcome his flaw. But then all of these things (either bit by bit or all at once) should come crumbling down on top of him. He should lose the girl. He should fail to defeat the villain. He should fall back into his own ways. The last 10-15 pages of your second act is the steady decline of your main character, ending with him at the lowest point of his life. Neo unable to defeat Smith in the train station. Kristin Wiig losing her boyfriend and best friend in Bridesmaids. The Man In Black LITERALLY dying in The Princess Bride. The end of your second act should LOOK like it’s over for you character. That there’s no hope. And with that my friend, you’ve done it. You’ve concluded your second act and are ready to cross into the third.

There you go folks. Pat yourself on the back. I just want to leave you with one warning. What I’ve given you is the template for a TRADITIONAL SECOND ACT. One which includes a character who’s going after a clear goal. Unfortunately, not every movie follows this template. There is no character goal in The Shawshank Redemption. Will is not going after anything in Good Will Hunting. Ditto the characters in When Harry Met Sally. So it’s important to remember that while these tips give you a starting point for navigating your second act, there is no one size fits all solution. For example, there are no unresolved relationships being mined in the second act of Taken. Could there have been? Sure. Would they have made the movie better? Maybe. But the point is, every story is unique, and the big challenge will be putting yourself in enough screenwriting situations where you begin to understand which of these elements are needed and which aren’t. But hey, you’ve got yourself a starting point. Which is more than some of these professional writers can say. Feel free to leave your own Second Act tips in the comments section.

Yesterday, Joshua James hit us with The Jones Party, which sparked some pretty intense reactions (you can download the script here)! Although it was his first script, it’s been optioned twice and gotten him a ton of assignment work. I thought it was a really solid piece of writing, Some of you thought it was way too “20s-ish.” Whatever happened to letting people in their 20s hate?? That’s what our 20s are for! But in all seriousness, I was happy when Josh agreed to do an interview for the site. Amateur writers need to be aware that there aren’t just 2 types of screenwriters, madly successful ones and starving artists, but that the majority of writers fall somewhere in the middle, fighting for assignments while they belt out the spec they hope will put them on the A-list. Josh has a blog where he gets into a lot of this in detail, but I thought I’d pick his brain for some finer points here on Scriptshadow.

JJ: The following is only what I’ve experienced, it makes me no better or worse than anyone else. We are all flawed and imperfect creatures, which is oftentimes the source of great fun and / or embarrassment, oftentimes both at once.

SS: Now my understanding is that The Jones Party got you both your manager and your agent. Can you talk about that in more detail? How did you get the script into their hands? Did you know someone or was it a cold query?

JJ: It wasn’t quite like that. I was a playwright in NYC and had plays going on in the indie theatre scene, so I met people through that, some development people, etc.

I wrote Jones and gave it to a theatre producer / actor who’d produced some of my plays, he loved it and optioned it, tried to get it made with himself as the lead, but didn’t … he ended up making another film instead … happily, we’re still friends.

The option expired and then someone else optioned it, and that expired and then I hung onto it for awhile, turning down offers on it in hopes of finding a way to direct it myself. All the while, I wrote other scripts.

Through another friend, I was introduced to a director-producer named Ken Bowser, who had done some cool documentaries (he’s got a really great one out now about Phil Ochs) and he loved Jones and optioned it. Ken worked with me on developing Jones and I cannot understate how much I learned from him during this time.

Ken also had the rights to a book I’d read and loved, Peter Biskind’s Down & Dirty Pictures, that he was also developing as a feature rather than a documentary (Ken had also done Biskind’s Easy Riders, Raging Bulls as a doc as well, which I had seen).

Now, I’d read Down & Dirty Pictures at least fifty times, I mean, I was a huge fan of the book and that era (the indie boom), and every time we met to work on Jones, I’d asked him how the book project was coming, heheheh … you know, just asking …

Turns out, the project was stalled, they’d had a writer on it but it wasn’t working out, the guy didn’t really get the material … I got a chance to pitch for it, offered a fresh take that Ken loved and I got the job. That was my first real job.

All of the above happened because I had Jones Party to show around, it opened a lot of doors for me, and got me quite a few meetings and other gigs, too (besides Down & Dirty Pictures).

At the time that I was hired on Down & Dirty Pictures, I had no representation, I’d left the agent and the manager I’d had back then (more on that later) and used an entertainment lawyer to handle the deal.

In terms of representation, initially Jones did get me repped, but not by the people I’m represented by now. When I first wrote it, a friend introduced me to an agent at a NY office who offered to rep me immediately and I agreed without hesitation.

This was a mistake.

I made the same mistake with a couple NY managers later on. They were the wrong fit, let’s say. One manager was a nightmare, you have no idea. He’s not even in the biz anymore. Shit happens, though.

I’d been given the following advice early on, and I should have heeded it but didn’t, said advice being: It’s better to have no representation than it is to have bad representation or the wrong representation.

I scoffed at this at the time, but now I can see that’s indeed true. I should have stopped worrying about agents and focused harder on my work. If you write enough scripts that people love, you’ll find the right people to represent you.

The Jones Party led to me getting hired to adapt Down & Dirty Pictures, and a good friend of mine (name redacted so he’s not swamped with requests) passed that script onto Dan, my current manager, and he loved it. We met a few times to talk and see if we were simpatico and it turns out, we are.

Dan’s awesome, and while working with him I wrote the original thriller A Black Heart, which led my current agent, who is also awesome.

Write a great script, and, if possible, write more than one and then the right representative will find you. Everyone wants to read a great script.

Everyone.

SS: The Jones Party was your first script. That’s mighty impressive, since it’s universally known that 99.9999% of all first scripts are terrible. What advice would you give to writers so that their first script comes out as good as The Jones Party?

JJ: Hmm … I guess I’d offer the following advice when it came to first screenplays.

1) With regard to Jones Party, I had something really specific to say about the subject matter, something unique and personal, personal to me, anyway.

I think having something to say is what got the interest of the people who saw potential in the script even in its earliest form, it’s why it was optioned right away (and multiple times after) and it’s a reason why different folks, especially Ken, spent a lot of time working with me on it, because the story spoke to them.

And it spoke to them because the story was saying something.

2) It’s fair to say that the early versions Jones Party were rough, no doubt, and not as polished as the version you read, and though the actions and characters and their journey were essentially the same then as they are now, but it was probably a harder read then, much rougher.

I’m lucky in that some people who knew more than I gave me great feedback on it and I listened to them. I listened to Ken. I think that’s the second piece of advice I’d give.

I chose to listen to people in the know (which isn’t everyone, but it is usually more than one someone) and take their feedback to heart.

You can’t (and shouldn’t) listen to everyone, but you should listen to someone and it should be someone smarter and more experienced, if at all possible, and at the very least someone who can tell you hard truths.

A writer needs at least one person in their life like that. You have to trust someone, even Stephen King has at least one trusted reader (his wife, Tabitha) who will tell it like it is and he’ll listen … I’m lucky in that I have more than one.

If you don’t know anyone to ask for feedback, I would recommend taking a class or joining a free online group, like Trigger Street, for example.

My good friend Scott teaches an online class, http://screenwritingmasterclass.com/ … Scott’s one of the smartest guys out there. Yeah, that’s a plug, but seriously, Scott’s a great guy and really knows his stuff.

3) The last thing is that I kept writing scripts, I worked on other screenplays, and each script taught me something new and I brought that back with me when it came time to polish Jones again.

They say you won’t really get it until you write at least ten of them. Jones was my first, but I wrote a bunch more after that and applied what I learned in subsequent rewrites and improved it and my craft. I definitely learned more about myself as a writer after script ten, no doubt about it.

To sum up:

1) Have something to say, something real and unique.

2) Listen to how trusted folks in the know respond to what you have to say.

3) Write more scripts.

SS: The thing that most impressed me about The Jones Party was the dialogue. What’s the secret to writing good dialogue would you say?

JJ: I’m gonna be a dick and link to a thing I wrote about dialogue on my blog.

I really just try to listen, that’s the thing, I try to imagine real people who care about real things and listen to what they want and what they have to say … and then cut out the boring parts. That last thing is the most challenging.

SS: A huge issue I have with amateur screenplays is that I only remember 1 or 2 characters after they’re over. Here, there a bunch of characters who pop off the page. What’s your approach to character? Do you write up character bios? Do you try and make sure your characters arc? Can you tell us a little about your process?

I don’t know if I have a process or if I just have a lot of voices in my head – LOL!

I just strive to make my characters real if I can, real to me, and if that’s not working, then I put real people from real life into my story … there is a real life Danno, after all. There was a Hope in my life, at one point. I have actor friends, and I will subconsciously plug them into a story.

I come from an acting background, I did a lot of it (oh me or my, the Meisner Training. The Meisner Training? The Meisner Training. The Meisner Training? That’s an inside joke … hardly anyone will get that) and so a lot of what I do with regards to character work is rooted in that. I put myself into a character whenever I can.

Also, I love what the FBI profilers say when figuring out who the killer is …

What plus Why equals Who.

I always found that very useful.

SS: The script also has an offbeat structure, in that it’s jumping back and forth and covering many different characters. How much emphasis do you put on structure as opposed to, say, writing by the seat of your pants?

You can write by the seat of your pants and still worry about great structure, structure isn’t story, per se (I’m possibly gonna get roasted in the comments for that) but rather it’s how the story is put together.

How I view structure regarding scripts and stories, is:

1) Story is what happens.

2) Character is who it happens to.

3) Structure is how it happens.

So whether you’re writing by the seat of your pants or plotting everything out beforehand by the page, via scriptments, you still want it be be as cool and efficient as possible.

Jones is structured in the way it is to get maximum impact in as short of time as possible … you could start at the chronological beginning (two years before the party, when Derwin and Hope first meet) and follow the story until we get to the party, but I don’t think the story would deliver the same emotional punch as it does now.

How it happens now, structure-wise, it maximizes the impact, I think. Folks are free to disagree. But the point is to tell the story as fast and efficiently as possibly.

The story is about these people participating in a Jim Jones Party and why.

Writing by the seat of the pants is fun, and that’s how I wrote Jones, I mean, I had no fucking idea how I was gonna end it when I started.

But I did know, in a way, when and where I wanted it to happen in the story, so I guess you could say I had an inner structure clock in my head. I had the where and when, just not the what. The what is the story, not the structure.

But writing without knowing the end is not always practical, either … if you’re working on a spec, it can be cool to write yourself into a corner and take weeks or months to get out of it. But if you’re on an assignment, that’s not so cool. And there’s something to be said for writing a bad ending so you’ll have something to fix later.

These days I usually do a treatment or an outline, just to work faster. But not always, it depends. Different genres, different types of movies have different demands in order to realize their impact, or potential … I don’t think that there’s ONE structure to rule them all, it has to be the right structure for right story …

I think Dirk Nowitzki has the perfect structure for a basketball player, but a terrible one if he wanted to be a horse jockey. He’s seven feet tall. He’d need a vastly bigger horse.

Speaking of big horses, the real action in the Godfather doesn’t start until Vito is gunned down, some forty minutes into it. That’s perfect for that movie. It wouldn’t be perfect for, let’s say, Meet The Parents (actually, I haven’t seen that movie, but I’m presuming Ben met DeNiro earlier than forty minutes into the movie) as an example.

Everything has a structure, everything … even bad scripts. The problem is that the structure is either an incomplete or not efficient or serving the story’s needs. Good ideas told badly are usually one or the other.

Or the story isn’t compelling or just bad … you can write a perfectly structured story that doesn’t work … I remember something a friend wrote about Goethe about criticism:

Goethe asked three questions:

1) What was the author’s intent?

2) How well was it done?

3) Was it worth doing?

And I try to keep that in mind when going back over my own work. I try. Maybe ten years from now I’ll think differently … I accept evolution as an established scientific theory.

SS: The Jones Party feels like a very personal story. Which leads me to the age old question. Do you think writers should try to break in with a high concept screenplay that they don’t necessarily have a personal connection with, or something more low-concept (like The Jones Party) that’s extremely personal to them? Obviously, The Jones Party falls into the latter category, but I’m interested to hear if you think that’s right for everyone.

JJ: It’s not high concept? A feel-good movie about suicide isn’t high concept? LOL!

I believe you have to write what you’re passionate about.

If you’re passionate about big movies, write about those stories, if you’re passionate about smaller, more intimate stories, write those. I happen to be passionate about both.

I was, and still am, very passionate about this particular story (Jones), as others have been, it’s a unique story, one not about people dying but about people finding a reason to live, an idea which really moves me … it is indeed very personal.

I’m also very passionate about Down & Dirty Pictures (I am an ex-video store clerk-geek, after all) to a rather ridiculous degree, I love-love-love movies and what they’ve done for my life … so it was a pleasure to write about guys who loved movies as much (if not more) as I did, which is what Down & Dirty Pictures is about, at its essence. It’s about guys who love film and movies so much it hurts.

Who among us here can’t identify with that? LOL!

But I’m passionate about a lot of things … I love thrillers, for example.

Action thrillers, I love stuff like that, and it’s no accident that I’ve written more and more stories like that, not just screenplays, but short fiction, novels (I have a couple crime novels I tinker with in my spare time) … anyone who knows me can attest, I love films like that. Always have. I don’t write those only because they’re high concept, I write them because those types of stories turn me on.

When my manager and I first met and had a series of meetings, we found we both shared a love of the classic suspense and action thrillers from the sixties and seventies, and spoke about what we’d like to see that hasn’t yet been done, and my script A Black Heart is a direct result of those conversations … I’m very drawn to those types of stories.

I love those kind of movies (I grew up on Lethal Weapon, in fact, and don’t get me started on Bruce Lee movies) and I’m passionate about them to a ridiculous degree. And kung fu flicks! Oh man. I can go on and on (I LOVED Taken, and again I’ll probably get roasted for that in the comments, but I loved it, man) until my wife tells me to shut up already …

I’m also passionate about people, certain characters, both living and dead and also ideas, there are many, many ideas I’m passionate about.

And there are probably things that I’ve not yet discovered that I may be passionate about, you know? I just recently discovered something new and cool and dove right into it. That’s part of evolving, after all … everyone does it. You find new things to love.

How long ago was it that almost no one knew the difference between standard poker and Texas Hold ’em? Now most folks do.

We live and we grow and the only thing constant is the change.

I think it’s important to write what moves you, what excites you. Whatever that is.

For me, there are many things that move me, I get excited about a lot of different things, a lot of characters and ideas, love, life, living, dying … and while it’s good to think about concept, it’s also good to make sure the idea is something that really moves you.

SS: I know you read a lot of scripts to keep yourself sharp. What would you say is the biggest difference between a pro script and an amateur script?

JJ: The biggest difference is that when you’re reading a well written script, you often forget you’re actually reading it … you may not even see the words, you just see the people in the story and you’re dying to know what happens next.

A professional usually has no unnecessary space, words … nothing unnecessary on the page and as a result the story moves like a freight train.

I read the Fight Club screenplay, because I wanted to see how the adaptation was done … it’s like 144 pages and I blinked and was at the end before I knew it (and hell, I’ve seen the movie and read the book, so I knew what happened, but still it drew me in). It moves.

No fat.

I read Taken, which has long blocks of action, and it flew by. No fat on that, whatsoever. Good writing, regardless of format, just flies by.

SS: Kyle Killen, the writer of The Beaver, likes to tell the story about how his wife got pregnant and he had nine months to make it as a screenwriter or forever be miserable in a “real” job. He sold The Beaver with a few days to spare. Let’s play make believe. If you had to start over, what would your plan be to make it as a screenwriter if you only had 9 months?

Wow, I so had the opposite reaction when my wife got pregnant!

Seriously, I was working part time and busting my ass as a writer, making a couple grand here and there writing scripts for others, and when she told me she was pregnant I stopped and got a full time job as an office manager right away.

This was right around the time I left a bad agent, too. I thought, well, I had a good run but now I’m gonna make sure I can feed my kid. I’m gonna be a responsible dad.

I let Jones get optioned, to Ken, which in turn led to the Down & Dirty Pictures job a few months later, I left the office job as a result and have been fortunate enough to be able to work as a writer since then.

But in answer to your question, you realize that it’s not make-believe, right? It actually is that way, in a fashion, for everyone … we all have a limited amount of time.

You may only have nine months, you may have a week, you may have to do it early in the morning before your day job, late at night and on the weekends … you may be broke and unemployed … I was unemployed when I wrote the very first draft of Jones, I gave myself two weeks to write it, sat in a cafe and pounded it out, not sure where I was gonna get money for food (this was, happily, before I was married and a father) …

I wrote that draft, then got a crappy part-time job … kept going, kept writing and working and living and breathing.

You may have to completely start over, more than once.

You have until the money runs out, and even then, you can still keep going, you only have until your will and urge to do so runs out.

You have until the end of your life, but when is that? Fifty years. Ten? A week? Tomorrow? No one knows, right?

My friend Scott Myers has said, “Writing doesn’t owe anyone a living” and that’s so very true, so if you’re doing it, do it because you love it, and try (this is hard) to write like there’s no tomorrow.

Kyle’s a brilliant writer, if he hadn’t sold The Beaver by the time his wife gave birth, he would have eventually written something else that sold, even while at a crappy day job, had he wanted to. And I think he would have, some people, they have to write, they can’t help it, they absolutely have to.

Sounds to me like Kyle wrote like it was his last shot.

The trick is to write everything like that, every day.

I believe that.

Tomorrow is promised to no one, therefore the plan is the same as it always is … work hard, work smart, be grateful for good fortune and especially to those people in my life who enrich it and be certain to repay them by making the most of every moment.

If everything ends tomorrow, what note would you want it to go out on?

SS: Being a paid writer, you experience a part of the business that there’s very little information on – trying to land writing jobs. Can you put us in the room of an assignment meeting? What do you think the key is to landing a job?

As that I live in NYC, a lot of stuff is over the phone …

I sold a pitch once, over the phone, and I had a list of ideas I was going down and I couldn’t see the guys I was talking to, obviously, they didn’t say much (other than, nah, not that one) and so I had no real idea how I was doing until I got to the one they liked, and that was, yeah, we like that, we’ll take it … what an experience that was, man! Can’t see them, can’t really hear them well (on a conference call, that happens a lot). You’re talking into a phone, it’s hard … but hey, I’m talking to someone who’s interested in my ideas, so I’m not complaining!

You just have to talk ideas, paint the movie out verbally and be positive, I think.

They want to see the movie, I’ve been hired a few times to write something for someone, they had an idea for a movie but didn’t know how to make it breathe as a film, make it work, that’s the key to landing jobs like that … how do you make it work?

You meet a lot of people, listen to what excites them, tap see the movie they want to make but haven’t yet and, if you can, solve that problem for them …

I was hired to help polish Cat Run (more here: http://writerjoshuajames.com/dailydojo/?p=2104) and it was about two weeks before they started shooting, yikes… we’d had a couple conference calls and the rest by email … now, that close to shooting, there’s very little time for messing around, the director doesn’t want to debate you about story or character, what you’re really there for is to solve his problems.

The director has this script section he’s not happy with and needs it to work … how to solve it? You throw ideas out there, he throws them back and so on until we find the one he likes and says, write that, get it to me by tonight. He’s in Europe (or wherever they were shooting) and I was in NYC, just busting out pages. My job was to solve his problems. He doesn’t have time for anything else other than that, and nor should I.

That’s what I did, in a sense, was help solve the third act and the finale, how do they get into the castle, how do they do this, how do they do that, all in a way that was cool … you really have to lose the ego, then, and just focus on doing the work. It’s not about words, at that point, it’s about making the story work in a way that makes them happy. And having fun, too. I had fun on that project, even though I know a lot of what I was writing was going to be changed once they got on set. I had fun.

The thing to remember is, everyone in the movie business loves movies as much as you do … they all want to make cool movies, but everyone gets jammed up (yeah, everyone gets jammed up, everyone, some of us just lie about it much better than others) on a project they love and if you can solve the problem and clear the log-jam for them, you’re gold, Pony-Boy, gold.

SS: Over the years, you’ve probably heard hundreds of screenwriting tips and pieces of advice. What advice would you say has influenced you the most? What tips would you say still guide you today?

JJ: Man, I can’t write everything that’s influenced or guided me the most, I’ve already yammered on past the point of maximum density as is.

Tell you what, I’ll share two simple things that directly impacted my life and career and still do … they’re simple yet I’m amazed at how often I have to remind myself about them.

1) Don’t waste a moment.

I had that insight one day, that every word, every character and every moment in the story should count … I was dumbfounded when I looked at what I was working on then, lots of time I had filler scenes, filler conversations, filler characters, stuff that killed time until we got to the good part.

I realized that every moment had to matter, every character, every line had to be something. It all had to be the good part. Once that hit me, much changed. It’s hard to follow through, though, real hard. But a good hard.

2) One day I realized that all I want from a movie, a book, a song or a story is to be moved. And as that I’m no different than anyone else, ergo, that’s all anyone else wants.

Because my original Aliens post is still somewhere in Blogger’s belly, I’m reposting it until they belch it back up. Unfortunately, that means that the previous comments won’t show up here, and any new comments you post won’t show up when I bring back the original post. But for reading purposes, here you go. :) (thank Clint Clark for getting this for me)

Aliens is, quite simply, awesome. It’s one of those movies that works if you’re 15 or you’re 35. It’s got action. It’s got mystery. It’s got emotion. And it’s in the running for best sequel ever. When I give notes, there’s no movie I reference more than this one. I’ve been known to bring up Aliens while consulting on a romantic comedy. That’s how rich it is in screenwriting advice. Now I could sit here and whine that “Studios just don’t make summer movies like this anymore.” But the truth is, they’ve never made these kinds of summer movies consistently – movies with depth, movies with thought, movies where the story takes precedence over the effects. But when they do, it’s probably the best moviegoing experience you can have. So, keeping that in mind, here are ten screenwriting lessons you can learn from one of the best summer movies of all time.

KILL YOUR BABIES

Listening in on the director’s commentary of Aliens, you find out that Aliens was originally 30 minutes longer, as it included an extra early sequence of the LV-426 colonists being attacked by the aliens. Under the gun to deliver a 2 hour and 10 minute film, Cameron reluctantly cut the sequence at the last second, and wow did it make a difference. Without it, there was more build-up to the aliens, more suspense, more anticipation. We were practically bursting with every peek around a corner, every blip of the radar. Now Cameron only figured this out AFTER he shot the unnecessary footage, but let this be a lesson to all of us screenwriters. Sometimes you gotta get rid of the things you love in order to make the story better. Always ask yourself, “Is this scene/sequence really necessary to tell the story?” You might be surprised by the answer.

NOT EVERY FILM NEEDS A LOVE STORY

There’s a temptation to insert a love story into every movie you write, especially big popcorn movies, since the studios are trying to draw from every “quadrant” possible and therefore need a female love interest to bring in the female demographic. But there are certain stories where no matter what you do, it won’t fit. And if you’ve written one of those stories, don’t try to force it, because we’ll be able to tell. I thought Cameron handled this issue perfectly in Aliens. He knew a love story in this setting wasn’t going to fly, so instead he created “love story light,” between Ripley and Hicks, where we see them flirting, where we can tell that in another situation, they might have worked. But it never goes any further than that because tonally, and story-wise, he knew we wouldn’t have accepted it.

ALWAYS MAKE THINGS WORSE FOR YOUR CHARACTERS

As I’ve stated here many times before, one of the most potent tools a screenwriter possesses is the ability to make things worse for their characters. In action movies, that usually means escalating danger whenever possible. Aliens has one of the most memorable examples of this, when our characters are moving towards the central hub of the station, looking for the colonists, and Ripley realizes that, because they’re sitting on a nuclear reactor, they can’t fire their guns. The Captain informs his Lieutenant that he needs to collect all of the soldiers’ ammo (followed by one of the greatest movie lines ever “What are we supposed to use? Harsh language?”), and now, with our marines moving towards the nest of one of the most dangerous species in the universe, they must take them on WITHOUT FIREPOWER. Always make things worse for your characters!

USE YOUR MID-POINT TO CHANGE THE GAME

Something needs to happen at your midpoint that shifts the dynamic of the story, preferably making things worse for your characters. If you don’t do this, you run the risk of your second half feeling a lot like your first half, and that’s going to lead to boredom for the reader. In Aliens, their objective, once they realize what they’re up against, is to get up to the main ship and nuke the base. The mid-point, then, is when their pick-up ship crashes, leaving them stranded on the planet. Note how this forces them to reevaluate their plan, creating a second half that’s structurally different from the first one (the first half is about going in and kicking ass, the second half is about getting out and staying alive).

GET YOUR HERO OUT THERE DOING SHIT – KEEP THEM ACTIVE

Cameron had a tough task ahead of him when he wrote this script. Ripley, his hero, is on the bottom of the ranking totem pole. How, then, do you believably prop her up to become the de facto Captain of the mission? The answer lies inside one of the most important rules in screenwriting: You need to look for any opportunity to keep your hero active. Remember, THIS IS YOUR HERO. They need to be driving the story whenever possible. Cameron does this in subtle ways at first. While watching the marines secure the base, Ripley grabs a headset and makes them check out an acid hole. She then voices her frustration when she doesn’t believe the base to be secured. Then, of course, comes the key moment, when the Captain has a meltdown and she takes control of the tank-car and saves the soldiers herself. The important thing to remember is: Always look for ways to keep your hero active. If they’re in the backseat for too long, we’ll forget about them.

MOVE YOUR STORY ALONG

Beginning writers make this mistake constantly. They add numerous scenes between key plot points that don’t move the story forward. Bad move. You have to move from plot point to plot point quickly. Take a look at the first act here. We get the early boardroom scene where Ripley is informed that colonists have moved onto LV-426. In the very next scene, Burke and the Captain come to Ripley’s quarters to inform her that they’ve lost contact with LV-426. You don’t need 3 scenes of fluff between those two scenes. Just keep the story moving. Get your character(s) to where they need to be (in this case – to LV-426).

THE MORE UNLIKELY THE ACTION, THE MORE CONVINCING THE MOTIVATION MUST BE

You always have to have a reason – a motivation – for your character’s actions. If a character is super happy and loves life, it’s not going to make sense to an audience if they step in front of a bus and kill themselves. You need to motivate their actions. In addition to this, the more unlikely the action, the more convincing the motivation needs to be. So here, Burke wants Ripley to come with them to LV-426 as an advisor. Answer me this. Why the hell would Ripley put herself in jeopardy AGAIN after everything that just happened to her – what with the death of her entire crew, her almost biting it, and barely escaping a concentrated acid filled monster? The motivation here has to be pretty strong. Well, because the military holds Ripley responsible for their destroyed ship, she’s basically been relegated to peasant status for the rest of her life. Burke promises to get her job back as officer if she comes and helps them. That’s a motivation we can buy.

STRONG FATAL FLAW – RARE FOR A SUMMER MOVIE

What I loved about Aliens was that Cameron gave Ripley a fatal flaw. Usually, you don’t see this in a big summer action movie. Producers see it as too much effort for not enough payoff. But giving the main character of your action film an arc – and I’m not talking a cheap arc like alcoholism – is exactly what’s made movies like Aliens stand the test of time while all those other summer movies have faded away. So what is Ripley’s flaw? Trust. Or lack of it. Ripley doesn’t trust Burke. She doesn’t trust this mission. She doesn’t trust the marines. And she especially doesn’t trust Bishop, which is where the key sequences in this character arc play out. In the end, Ripley overcomes her flaw by trusting Bishop to come back and get them. This is why the moment when she and Newt make it to the top of the base is so powerful. For a moment, she was right. Bishop left them there. She never should’ve trusted him. Of course the ship appears at the last second and her arc is complete. She was, indeed, right to leave her trust in someone.

SEQUENCE DOMINATED MOVIE

One way to keep your movie moving is to break it down into sequences. Each sequence should act as a mini-movie. That means there should be a goal for each specific sequence. In the end, the characters either achieve their goal or fail at it, and we then move on to the next sequence. Let’s look at how Aliens does this. Once they’re on LV-426, the goal is to go in and figure out what the fuck is going on (new sequence). Once they find the colony empty, their goal shifts to finding out where the colonists are (new sequence). After that ends with them getting attacked by aliens, their goal becomes get off this rock and nuke the colony (new sequence). Once that fails, their goal becomes secure all passageways so the aliens can’t get to them (new sequence). Once that’s taken care of, the goal is to find a way back up to the ship (new sequence). Because there’s always a goal in place, the story is always moving. Our characters are always DOING SOMETHING (staying ACTIVE). The sequence approach is by no means a requirement, but I’ve found it to be pretty invaluable for action movies.

ACTIONS SPEAK LOUDER THAN WORDS (SHOW DON’T TELL!)

Aliens has one of the best climax fights in the history of cinema (“Get away from her you BITCH.”) And the reason it works so well? Because it was set up earlier, when Ripley shows the marines she’s capable of operating a loader (“Where do you want it?” she asks). Ahh, but I have a little surprise for you. Go pop Aliens in and fast-forward it to the early scene where Burke first comes to recruit Ripley. THIS is actually the first moment where the final fight is set up. “I heard you’re working the cargo docks,” Burke offers, smugly. “Running forklifts and loaders and that sort of thing?” It’s a quick line and I bring it up for an important reason. I bet none of you caught that line. Even if you’ve watched the film five or six times. That line probably slipped right by you. And the significance of it slipping by you is the point of this tip. You should always SHOW instead of TELL. When we SEE Ripley on that loader, it resonates. When we hear it in a line, it “slips right by us.” Had we never physically seen Riply on that loader, and Cameron had depended instead on Burke’s quick line of dialogue? There’s no way that final battle plays as well as it does. Always show. Never tell.

AND THERE YOU HAVE IT

I actually had 15 more tips, but contrary to popular belief, I do have a life, so those will have to wait for another day. I do have a question for all Aliens nerds out there though. How do they pull off the Loader special effects? I know in some cases it’s stop motion. And in other cases, Cameron says there’s a really strong person behind the loader, moving it. But there are certain shots when you can see the loader from the side that aren’t stop motion and nobody’s behind it. So how the hell does it still look so real? I mean, these are 1986 special effects we’re talking about here! Tune in next week where I give you 10 tips on what NOT to do via the disaster that was Alien 3.

Genre: Love Story/Drama/Comedy?

Premise: After eternal ladies’ man, Todd, falls in love for the first time, he must learn to get along with his new girlfriend’s overbearing father, Harry.

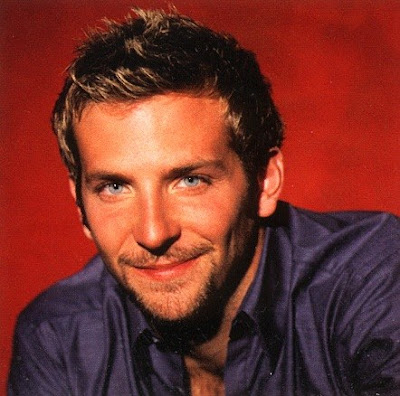

About: Honeymoon With Harry is a project that’s been kicking around Hollywood for awhile, and is thought to be one of the better unproduced screenplays out there. It’s based on an unpublished novel by Bart Barker, which is also supposed to be really good (I don’t know why it’s never been published). The project is set to star Robert De Niro and Bradley Cooper (though De Niro’s been waffling recently) with Johnathan Demme directing. This is an early Paul Haggis draft (from 2004) and I guess there have been a lot of writers since, with the most recent being Jenny Lumet, who wrote Rachel Getting Married.

Writer: Paul Haggis

Details: 131 pages – November 8, 2004 draft (This is an early draft of the script. The situations, characters, and plot may change significantly by the time the film is released. This is not a definitive statement about the project, but rather an analysis of this unique draft as it pertains to the craft of screenwriting).

Paul Haggis is a solid writer. The guys knows his shit. So after watching/reading his last two writer-director projects, The Next Three Days and In The Valley Of Elah

, I guess you could say I was disappointed. Neither script was bad. But neither was that good either. You know how I pointed out the other day in my Breakfast Club breakdown that every script needs a few “memorable moments?” The bag blowing scene in American Beauty

? The egg-eating scene in Cool Hand Luke

? Neither of those Haggis films had any memorable moments. You forgot about them as soon as you left the theater. This was surprising, since Crash

, Haggis’ controversial but most accomplished effort, had a ton of memorable moments. Having heard on several occasions that Honeymoon With Harry was one of the best unproduced scripts in Hollywood, I was eager to see if he was sitting on a goldmine, something that brought him back to those Crash days. What I got instead was two movies wrapped into one.

The first of these movies is GREAT. It’s a love story. We have our hero, Todd, who admittedly sleeps with one too many women, instantly falling in love with Haley, who he meets at a bar. This girl is THE ONE. She’s sweet, she’s nice, she’s funny, she’s beautiful. And the dialogue between them is great. After noticing that she’s wearing a ring, he offers, “That’s one beautiful ring.” “Thank you.” “I’m hoping that the guy who gave it to you died in some tragic way and you’re wearing it to remember him.” A charmer indeed. But Haley’s no easy target. She takes his number and tells him she “might” call.

After sleepwalking through a few weeks of torture, Haley finally calls Todd and the two begin dating. And it’s…perfect. Even Billy Crystal and Meg Ryan would look at these two and say, “Wow, now that’s a couple.”

Of course no story works if your central couple is happy for too long. You have to introduce some element of conflict to give yourself a movie! And that conflict comes in the form of Harry, Haley’s overbearing powder keg of a father (who she still lives with). And the worst thing about Harry? He sees right through Todd. He knows his kind. And there is no way in hell he is allowing this piece of shit to be with his little girl.

This makes things pretty awkward because Todd isn’t about to give up. Even when Harry threatens to KILL HIM, Todd is right there the next day, inviting (or is it daring?) Harry to join he and his future wife for dinner.

And then – just like that – everything changes.

(MAJOR SPOILERS BELOW)

Halfway through the movie, Haley dies in a car accident. I have to tell you, since I didn’t see this coming, it was a shock. One of the things I always recommend here is that whatever your movie is about, make sure it starts being about that by page 30 (the end of the first Act). The reason is, if you wait all the way until halfway through the film to hit the main storyline, the audience is going to get impatient, or worse, confused. It’s just not the way people are used to digesting stories.

However by ignoring this rule, Honeymoon With Harry was able to surprise the hell out of us. So you have to give it to Haggis for that. I was devastated. I mean, I really liked this girl. And just like that – just like in real life – she’s gone. Where do you go from here?

The problem is that in the script world, the answer to that question poses all sorts of problems. Now that *that* story’s over, you have to start up a whole new story, and starting up a whole new story halfway into your screenplay is really fucking hard. And that’s where Honeymoon With Harry falters. Its second story isn’t one-tenth as interesting as its first one. And there are a couple of reasons for this. Todd and Harry.

I don’t know why the original author or Haggis did this. But Todd is a slimeball. I mean he’s a really sketchy dude. I didn’t mind him banging every female that strolled into the club BEFORE he met Haley because that was BEFORE he met Haley. But to keep doing it afterwards? I mean, HE FUCKS HALEY’S BEST FRIEND ONLY DAYS AFTER HER DEATH. And I get that it’s supposed to be an emotionally confused screw but still, it’s like the author is deliberately trying to make us hate this guy.

And yet despite this, Harry’s even worse! He’s mean, he’s abrasive, he’s an asshole, he’s irritating, he’s unruly, he won’t shut up, he whines, he’s a dick. There isn’t a single likeable trait on this man’s body. And yet he and the sperminator are who we’re spending the next 70 pages with! It’s like watching two people argue on Celebrity Rehab. You don’t care who wins cause you hate them both.

Oh yeah, I forgot to tell you what the rest of the movie is about. After Haley dies, Harry and Todd fly off to the tropical island where Haley wanted her ashes thrown. Despite each having their own ideas on how this should be approached, they must work together and compromise to get it done.

So I guess the big question is, how do you save this story? A much more traditional setup would have Haley dying at the end of the first act. Although if you do that, you lose that amazing mid-story surprise. But I don’t think you have a choice. It poses too many problems to change your story up so late in the game (plus people are going to know going in that she dies anyway). The bigger issue is that you have to rewrite Harry. This man needs a Final Draft intervention. Just an obnoxiously annoying person from top to bottom. I get that you need to create conflict between these two to keep the story juicy, but if it’s forced, if the character is all the way to one extreme, it’s never going to feel right. And Harry and Todd’s interaction never felt right.

A frustrating script with a lot of potential. I wonder if they’ve solved these problems by now (or if they even saw them as problems in the first place).

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: I feel, as writers, we go through phases in the way we write our protagonists. It starts when we learn how important it is to make our hero “likeable.” Once we learn that, we go to the extreme, making our hero the greatest nicest coolest most charming person ever. But after doing that for a few scripts, we realize it isn’t realistic. And that all that glitter and gold actually makes our hero feel artificial and off-putting. So we go through phase 2, which is to start adding unlikable traits to balance out the likeable ones. “Ahh,” we say, “You thought I was going to make this character perfect? Well how bout him dumping his girlfriend at her sister’s wedding! Now you’re not so sure about him, are you?” We do this for a few scripts, proud at how balanced our heroes become, but then somewhere around this time, we hit Stage 3, which is to start pushing the envelope on our hero’s unlikeability . I’m not sure why we do this but I think it’s to prove that we aren’t slaves to traditional screenwriting structure. We want people to know that we take chances. So we load up on the unlikeable traits, making sure they outnumber the likeable ones, and almost dare our audience to root for our character. The problem with this is, of course, that if you flirt too close with the edge, you run the risk of falling off it. And that’s what happened here, with both characters. When Todd is funny and charming, we like him. But then when he sleeps with some random chick on the night he meets the girl of his dreams? We hate him. And when he continues to bang girls at the tropical resort? We hate him more. And don’t get me started on Harry, who I don’t believe has any likeable traits. Once the unlikeable traits outnumber the likeable ones in your hero, your audience is going to turn on them. Never forget that.