Search Results for: 10 tips from

Okay, I’m going to be honest. I have an ulterior motive for today’s “10 Tips” post. Toy Story 3 was written by Michael Arndt. And as Star Wars geeks all know, well, Arndt is writing the new Star Wars film. So I guess I’m checking up on him. Now here’s the thing with Arndt. There are folks out there who have complained he’s a little too technical in his writing approach. To them, his movies feel “constructed” and “written,” and I’m trying to figure out why that is. I suppose Arndt struggled for a long time to break into the business (which he finally did with Little Miss Sunshine) and therefore had a lot of time to study screenplays. When you study the craft for that long, you get to know the innards of a screenplay really well. That vast knowledge may explain his uber-dependence on his craft. Having said that, I don’t share that point of view. I think Arndt is a really good screenwriter and was relieved when he got the Star Wars job because I knew, at the very least, the script wouldn’t suck. We had no such guarantees with the last three Star Wars films. For those unfamiliar with Arndt’s work, he wrote Little Miss Sunshine, Brave, Oblivion, and the upcoming, The Hunger Games: Catching Fire.

1) What is structure? – When we talk about structure, we’re typically talking about the three major acts your story will be divided into (setup, conflict, resolution), the goals driving your characters forward (the toys must get back to Andy before he leaves for college!), stakes and urgency (They have less than a week to get back to Andy. If they don’t, they’re stuck in this prison daycare center forever!), the major story beats along the way (i.e. Lotso is revealed to be an evil dictator!), and your character arcs (Woody must learn to let go of Andy!). These things need to be appropriately paced in order to keep your story interesting for its entire running time. A lack of (or a badly executed) structure will always result in your audience getting bored early.

2) The Structure Paradox – Here’s something I recently realized after reading a bout of bad scripts. The writers who don’t know structure are the ones who need to focus on it. And the writers who obsess over structure are the ones who need to pull back from it. Beginner writers want to blaze their own trails, do it “their way,” and ignore 100 years worth of storytelling knowledge. The problem is, they don’t know enough about structure to go against it, so their scripts are usually rambling, incoherent, and unfocused. Experienced writers, on the other hand, know how important structure is and therefore make it a priority. The problem with them is that they depend on it too much, which means their scripts lose any and all unpredictability, resulting in a lot of “run-of-the-mill” stories. It’s okay to break away from a planned story beat every once in awhile or have your character do something out-of-character. So if you’re a beginner, embrace structure. If you’re a vet, resist it every once in awhile. Your writing will get better.

3) The Invisible Man – Structure is the beams, the foundation, of your script. But just like a building, you don’t leave all those beams exposed, do you? No, you cover them up with walls, paint, pictures, plants, bookcases, until it’s impossible to imagine the skeletal framework it used to be. Screenplays are no different. You add the structure (the acts, the goals, the character arcs) and then you start exploring relationships, seamlessly transitioning your scenes, adding realistic dialogue, all the things that make that structure invisible. Being able to incorporate structure is great. Being able to incorporate structure INVISBLY is what separates the pros from the nos.

4) Real writers cover – Arndt says that a big part of his improvement as a writer came from covering scripts for production companies (meaning he read and broke down a script’s strengths and weaknesses). Having a gut reaction on a screenplay or a movie (“That script sucked”) doesn’t help you as a writer. It’s only when you specifically break down WHY it didn’t work for you that you begin to understand the inner workings of a screenplay. So if you’re not already, read some spec sale scripts and cover them. Or read the Amateur Offerings scripts (which I post every Saturday) and give your analysis in the comments section. Or give detailed notes to your friends on their scripts. However you go about it, analytically breaking down screenplays is going to make you a better screenwriter.

5) CONFLICT ALERT – Remember that conflict should be present in every single scene in your movie. An example of it here is when the toys arrive at the Sunnyside Day Care Center. All the toys are excited that they’ll now have a place to be played with. Everyone EXCEPT for Woody that is. Woody thinks they need to be back with their owner, Andy. His resistance adds the necessary conflict to keep the scenes lively. If everyone agrees they should be here, how interesting is that?

6) Set up expectations, then reverse them – Setting up expectations is a neat little tool you can use to juice up any part of your script. For example, when the toys are on their way to Sunnyside, Woody warns the others that it’s going to be terrible there. That’s the expectation. But they get there and it’s wonderful! Expectation reversed! Lotso the Bear is another expectation. He’s presented as a wonderful helpful leader. All the toys love this guy! But he turns out to be a heartless dictator. Expectations are essentially story twists, and since you always need 3-6 twists in every script, they’re a good tool to have at your disposal.

7) Dialogue Tip: Tweak well-known phrases – Well-known sayings or phrases are fun (“Are you ready?” “I’ve been ready my whole life.”). But in movies, you want to tweak them and make them unique to your characters. So at one point in Toy Story 3, Mr. Potato Head retrieves his old body. The well-known phrase he uses is, “You’re a sight for sore eyes.” The line, however, is tweaked to, “You’re a sight for detachable eyes.”

8) Michael Arndt never writes a script unless he knows the ending – If you know where your script ends, it’s much easier to plot it, since you know where all your characters need to end up. So if you want to make things easier on yourself, figure out your ending before you start.

9) A character’s disposition shouldn’t always match his appearance –Toy Story has made an entire franchise out of this, but it’s a great practice to use, even if you’re not writing an animated feature. Try to give a few of your characters traits that are the opposite of their appearance. So the T-Rex is a scaredy cat. The big cuddly pink bear is an evil dictator. His main henchman is a baby. Or, since JJ’s directing Arndt’s current Star Wars script, let’s look at JJ’s Lost. Sawyer, the big bully on the island, is an avid book reader. This practice almost always makes characters more interesting.

10) A Deus-Ex-Machina ending can work IF it’s properly set up – In the end of Toy Story 3 (spoiler alert!), the toys are about to fall into an incinerator when a GIANT CLAW comes down to save them. A total deus-ex-machina moment (the characters do nothing to get out of their own predicament. They’re saved by someone else). BUT, that claw happens to be operated by the little aliens who our characters first encountered in the original Toy Story (they were in the “Claw-Machine” at the arcade). Granted it was a bit of a cheat to use something set up 2 movies ago. But the point is, it WAS a payoff and therefore the deus-ex-machina did not feel like a deus-ex-machina.

Bonjour! Pardon, mon ami. Je m’appelle Carson!

That’s the extent of the French I know, despite spending 8 years of my life in various French classes (and having two tutors). How I passed any of those classes is a French miracle. But that’s not stopping me from stumbling through Paris and pointing to various pastries and saying “Une of those.” There’s a 60% chance I’ll be kicked out of here by Wednesday for my blatant Americanism. By the way, prepare for a 2 hour wait in the customs line if you ever come here. The line I was in was 500 deep and they had TWO customs agents. TWO!! They seem to have taken a cue from visiting the American post office. We should get those groups together sometime. So far I’ve been to Sacre Coeur, the Arc De Triumph, and some famous “steak frites” place that wasn’t half as good as a double double from In and Out. But man, the pastries and bread here put America to shame. If one of these guys was smart, they’d move to LA and make a killing. Then again, if I mange one more pain du chocolate, I might explode.

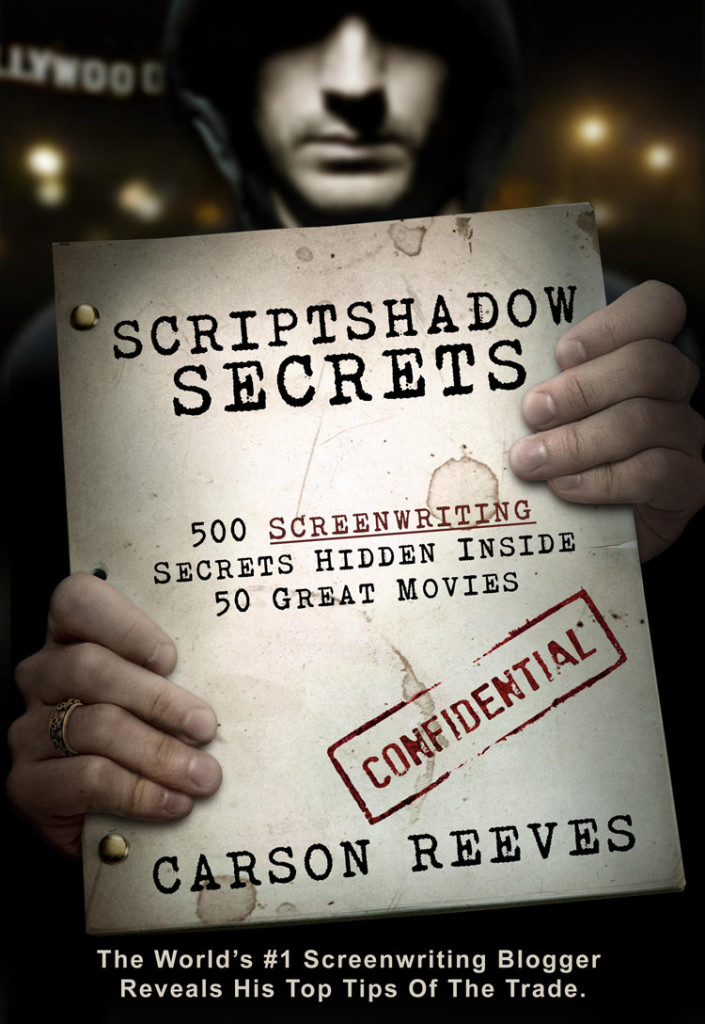

Anyway, because I’m not going to be posting this week, I’ve decided to make the Scriptshadow Secrets book half off. So if you’ve been putting off reading it, go buy it now. You’ll learn just as much from that book as probably half the posts I’ve posted here, since the tips are based on everything I’ve learned through all the scripts I’ve reviewed. Plus it’s just an awesome book! So start reading folks. And I will see you all dans une semaine!

PICTURES FROM PARIS – UPDATED DAILY!

Some famous bridge with a lot of locks on it.

Some famous bridge with a lot of locks on it.

Which SS commenter does this most remind you of?

Which SS commenter does this most remind you of?

Proof that Michael Cera is a vampire and has been around for 400 years

Proof that Michael Cera is a vampire and has been around for 400 years

Miss SS in front of Notre Dame!

Miss SS in front of Notre Dame!

Which commenter do you think THIS most resembles? (this should be easy)

Which commenter do you think THIS most resembles? (this should be easy)

Cows at Versailles! We ate them afterwards.

Cows at Versailles! We ate them afterwards.

A house on Marie Antoinette’s Estate. Kept looking for a bloody guillotine to no avail.

A house on Marie Antoinette’s Estate. Kept looking for a bloody guillotine to no avail.

Versailles Gardens. The French know how to spend money.

Versailles Gardens. The French know how to spend money.

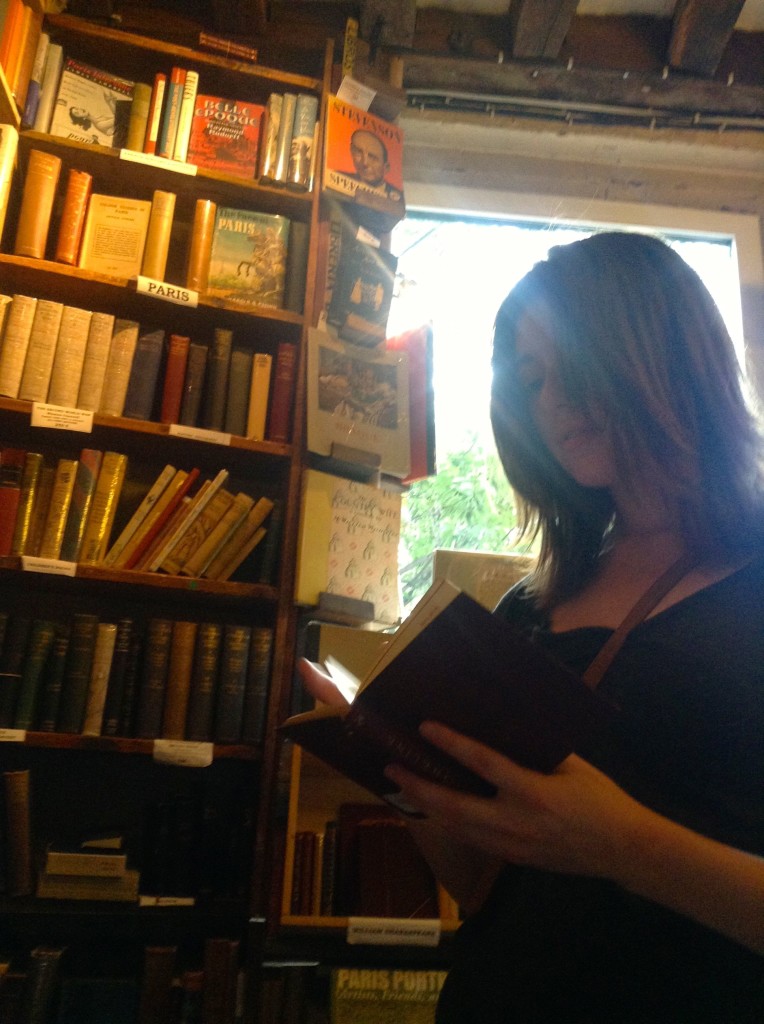

Miss Scriptshadow at famous bookstore, Shakespeare & Company (featured in Before Sunset)

Miss Scriptshadow at famous bookstore, Shakespeare & Company (featured in Before Sunset)

Had lunch with Isabelle Adjani, winner of 5 Cesars (France’s Oscar equivalent). She was very humble and sweet!

Had lunch with Isabelle Adjani, winner of 5 Cesars (France’s Oscar equivalent). She was very humble and sweet!

I tried to explain to these two that their puppet show didn’t have any goals, stakes, or urgency and I was promptly thrown out of Paris.

I tried to explain to these two that their puppet show didn’t have any goals, stakes, or urgency and I was promptly thrown out of Paris.

What I learned: Louvre in the rain results in a lot of character development.

What I learned: Louvre in the rain results in a lot of character development.

Miss SS had reached the “Really, you’re still taking pictures of me?” phase of the vacation when I took this.

Miss SS had reached the “Really, you’re still taking pictures of me?” phase of the vacation when I took this.

French Scriptshadow fan who showed us around.

French Scriptshadow fan who showed us around.

This is a rare pigeon sighting. As you know, there is a scarcity of pigeons in Paris since they eat them all.

This is a rare pigeon sighting. As you know, there is a scarcity of pigeons in Paris since they eat them all.

France did not only give us the Statue of Liberty. They gave us indoor malls! This is the first indoor mall ever! (p.s. The accuracy of this statement is based on my own educated guess and therefore has an 80% probability of being wrong).

France did not only give us the Statue of Liberty. They gave us indoor malls! This is the first indoor mall ever! (p.s. The accuracy of this statement is based on my own educated guess and therefore has an 80% probability of being wrong).

I was dared to walk up to one of these guys, lick them, and say, “That was finger licking good.” I did not accept that dare.

I was dared to walk up to one of these guys, lick them, and say, “That was finger licking good.” I did not accept that dare.

Last night at a restaurant I saw “baby pig” on the menu. I’m praying this is what they meant.

Last night at a restaurant I saw “baby pig” on the menu. I’m praying this is what they meant.

It took us 3 wrong Metro stops, 5 wrong-way walkings, 8 map screw-ups, and 2 arguments to find this freaking canal. But it was found!

It took us 3 wrong Metro stops, 5 wrong-way walkings, 8 map screw-ups, and 2 arguments to find this freaking canal. But it was found!

I’m not sure what Parisians would do if they saw that the average Los Angeles street was 9 times wider than this. They might stop eating baby pig.

I’m not sure what Parisians would do if they saw that the average Los Angeles street was 9 times wider than this. They might stop eating baby pig.

Miss Scriptshadow is always up for an adventure. Unfortunately, I haven’t seen her since she went on this one.

Miss Scriptshadow is always up for an adventure. Unfortunately, I haven’t seen her since she went on this one.

A few weeks back I extracted ten screenwriting tips from the movie Hoosiers. It’s right up there with Rocky as the best sports script ever written and probably one of the best scripts written period. So imagine my shock when I discovered that the writer had only two produced credits in the 25 years since that film! How does a writer that skilled not have producers knocking on his door begging him to write their next movie? That question really got me thinking about the way this industry works and how hard it is to write a script that gets purchased or made. There are people out there who actually believe it’s all a crapshoot, that any script that sells is luck.

Well before I get into why I don’t think that’s true, it’s important to note that there are some extenuating circumstances here. First, you probably don’t want to break into the industry with a sports script. There just aren’t many sports movies being made, so if you get pigeonholed as “the sports writer,” you’re going to have a tough time getting jobs. Also, just because you haven’t snagged any credits in a long time doesn’t mean you aren’t working. I’m sure Angelo Pizzo (the writer) has written on plenty of projects since Hoosiers that just never got made.

That doesn’t pertain to the amateur screenwriter because the amateur screenwriter isn’t being paid six figures to write anything yet. They have to generate their own material on their own dime. And that’s what leads us to today. You see, I don’t believe in crapshoots when it comes to screenwriting. I believe that if you follow today’s formula, you can place the odds of selling a script in your favor. And it’s actually quite simple. Ask yourself, who are the three most important people to impress with a screenplay? Why, the Producer, the Director, and the Actor (PDA) of course.

To understand this equation better, we must understand how a script is purchased. Typically, someone will send a producer a script (an agent, a friend, another writer, whomever). If he likes it, he’ll try to attach an actor to the material. Assuming he’s successful, he might then go directly to the studio to try and sell the script. But with studios wanting to do less and less work these days, the producer will also want to attach a director if possible. It makes the package more appealing and gives it a better chance of getting made. No matter how you look at it, at some point, these three people have to be lured to the script.

But what does that really mean? How do you write a script to satisfy these three folks? I’m about to tell you. And here’s the good news. Writing for these three people is actually going to make your script better. This isn’t something you must begrudgingly “fit in” to your script. It’s stuff that will improve the quality of your product. So now that you know who you have to impress, let’s discuss what these people are looking for.

PRODUCER

A producer is looking for a marketable project he can make money off of. True, each producer is different. They work in different genres and have different tastes. But they’re all looking for a movie that will make them money. Why? Because if you make money as a producer, you get to keep making movies. Except for the top top guys (and some would argue even for them), producing is a game of survival. If you don’t make money, you’re done. For this reason, a producer will pay close attention to the marketability of a project. Does it have poster appeal? Trailer appeal? Billboard appeal? Does it have an intriguing hook? Is there something about it that can be marketed? The best way to satisfy these questions is to come up with a good concept. Think something that’s going to bring in that male 14-30 demo. Robots (Transfomers), monsters (Pacific Rim), undercover agents (Safe House), a sexy reimagining (Snow White and the Huntsman). If big summer movies aren’t your thing, then write a fun comedy idea (I Love You Man) or a script with some irony in the logline (The King’s Speech). Even if you’re doing something low-budget, always ask, “Is this marketable to the demographic I’m shooting for?” “Buried” didn’t make a ton of money. But it was contained, cheap to shoot, and marketable. So it made money. Safety Not Guaranteed is another example of a low-budget concept that was marketable. If you’re not considering the question of whether your film can make money or not, you’re ignoring the first cog you must get your script past – the producer.

DIRECTOR

Let’s think about this. What does a director want? Well, put yourself in the director’s shoes. Or better yet, look at all your favorite directors and the kinds of movies they’re making. Directors tend to like interesting visuals, fun and inventive action, an aesthetic that hasn’t been done before, taking us to a time or place we haven’t seen before, new takes on old ideas, anything that allows them to play with the medium in an interesting way. 47 Ronin, Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind, Gravity, The Matrix, The Great Gatsby, Life of Pi. If you look at all the top directors in the business, you’ll see that they’re making movies within this rule-set. The easiest way to know if you’re writing a script for a director is to ask, “Would any of the top twenty directors in the world want to direct my script?” I mean really ask yourself that question. And be honest. Because getting a director attached to anything is EXTREMELY hard. They must dedicate 3-4 years to a film. So, for example, if all you have is a bunch of talking heads in your script – if that’s all you’re bringing to the table – I doubt a director’s going to waste 4 years on that. Now there are some caveats here. If you’re writing in comedy, it’s more about how funny the script is (although I’d contend that a comedy director would rather direct The Heat where he gets to move around and play around a lot, than say, Celeste and Jesse Forever, which is a lot more stagnant and boring to shoot). But in the end, as long as you believe the top directors in your genre would be interested in making your script, you’re in good shape.

ACTOR

I’ve talked about writing for actors enough that I’m sure I sound like a broken record by now. But this is probably THE most important factor in getting your screenplay sold. If you get one of the top 30 (A-list) actors attached to your script, your chances of making a sale go up a thousand percent. Why? Because these actors have proven they can open a film (meaning their studio films tabulate more than $25 million dollars on opening weekend). So if you’re a studio, you want the projects these guys are attached to. Now there’s a gamble for the studios because actors jump on and off projects all the time. But it’s a risk worth taking. Which brings us back to, “How do you write for an actor?” Compared to writing for a director, I personally think writing for an actor is much easier. An actor can make ten movies in the same amount of time a director makes one. So they’re less picky. Still, they want a good role to play, and that almost always means a role that shows off what they can do. Something that allows them to play a variety of emotions, something that allows them to show their range. Or just a really unique part. I recently reviewed Dan Gilroy’s latest script, Nightcrawler, in my newsletter (sign up here). The lead role (which Jake Gyllenhaal snatched up) was this talky slightly-crazed borderline autistic sociopathic success-whore who loses himself within the deranged bloody world of amateur news coverage. I mean what actor isn’t going to want to play that part! Or play the part of an emotionally dead female hacker (Girl With The Dragon Tattoo) or a character who wakes up in someone else’s body with no idea how he got there (Source Code) or a king who can’t speak (King’s Speech) or a crackhead who’s an embarrassment to his successful boxing brother (The Fighter) or hell, even an intelligent former CIA agent who gets to coldly kick ass for an entire film (Taken or Salt). Put simply, at least one of the main characters in your script should be INTERESTING, and to a lesser extent, FUN TO PLAY! If you don’t have that, it’s very unlikely your script will sell.

Okay, now that you know you SHOULD have PDA, I bet you’re asking, “Is it possible to sell your script WITHOUT PDA?” Of course. Anything’s possible. There are scripts that get away with only having two of the these three elements. For example, if you have a big enough concept – like say aliens attacking the earth (Independence Day or Pacific Rim), the concept ends up overriding the need for a big star. Which is why both films went with unknowns in the lead role (Will Smith hadn’t yet become a star before Independence Day). Also, some of the meatier acting roles occur in dramas that don’t have the biggest concepts (the kind producers love). I’m sure the producers of The Descendants, while excited to get George Clooney, weren’t exactly thrilled about the prospects of marketing the film. So just like everything else in the business, there’s no clear-cut answer. Sometimes in order to gain a little more of one thing, you have to lose a little of another. But I will say that if you can write that script that incorporates every element of PDA, and you’ve written a good story to boot, you will have positioned yourself for a spec sale. The best example, in my opinion, of PDA, is probably Pirates Of The Caribbean. It’s got all three of the elements in spades. So, what about you? Do you have PDA in your script?

Genre: Drama

Premise: When an escaped convict infiltrates the home of a single mother and her son, the mother unexpectedly falls in love with the man.

About: This is Jason Reitman’s next movie, which will star Kate Winslet, Toby Maguire and comeback kid James Van Der Beek! It’s slated for an early 2014 release. Reitman’s outshone his legendary director father (Ivan Reitman) as of late, directing well-received films like Juno and Up In The Air. But he better watch out. Ivan is about to make a comeback, getting ramped up to direct the mega-hot script Draft Day, starring Kevin Costner as a general manager during the most important day of the year for NFL teams, draft day.

Writer: Jason Reitman (based on the novel by Joyce Maynard)

Details – 125 pages (2/4/11 draft)

Jason Reitman is an interesting writer/filmmaker. He’s not making films like anyone else out there. Here’s the issue I have with Reitman though. I’m not sure who HE is. I know every director out there wants to be Ang Lee or Steven Spielberg, the kind of director who can jump in and out of genres effortlessly, but what’s the reason we go to see a filmmaker’s film? Because we know what kind of movie they make. Thank You For Smoking. Juno. Up In The Air. Young Adult. Where’s the common thread in those? I’m not sure I can find one.

It’s not to say someone can’t break the mold and make whatever movie they want, but it’s a hell of a lot of harder to gain traction as a filmmaker if that’s the route you’ve chosen. I think early in your career you need to pick one genre and stick with it, THEN break out. Right now, the thing Reitman is probably best known for is being the director of a couple of Diablo Cody scripts, and I’m sure that isn’t what he’d like to be known for.

To make matters worse, the only consistent element he’s got going in his films (they’re 30-60 million dollar dramas that sometimes contain comedic elements) is the exact kind of film Hollywood is trying not to make anymore. There’s no real hook to draw audiences in other than the acting, directing and writing, and it’s hard to get those things right. And these films don’t have much of an upside even if they DO do well. With Young Adult never really breaking out, this is a huge moment for Reitman. He’s gotta prove that there is an audience for these movies. And that’s going to be tough. Cause if Labor Day isn’t executed perfectly, it’s in a lot of trouble.

Labor Day tells the story of Henry…. Wait a minute. That’s not actually true. It tells the story of Adele… Actually, that’s not true. It tells the story of Henry, who’s TELLING A STORY about Adele. Yeah, so let me start over. It’s 1987. Henry is a 13 year old kid living in a small town with a single mother who’s still bitter about her divorce. She’s given up on love, and in the process, given up on life. The only thing she’s got going for her is Henry.

That changes when the two go shopping one day and are approached by Frank, who seems like a good guy with the exception of a few suspicious cuts on his body. Now you and I would probably walk away from this. But Adele, for whatever reason, decides to take Frank home with her, a man whom she later finds out is an escaped convict.

All of this is being recalled via voice over from Adult Henry, who’s basically remembering the crazy 4 day Labor Day weekend that occurred when his mother fell in love with a convict. Yup, poor Henry gets his sex education via the shaking and moaning and screaming that occurs in the bedroom next to his. It’s something he isn’t really sure how to handle. He thinks it’s strange that they have, you know, an escaped convict not only living with them. But having sex with his mom! Most people would consider that weird.

Eventually, Henry befriends a new girl in town, Eleanor, who puts two and two together and realizes Henry’s housing the fugitive. She eventually convinces him that he’s going to be cut out of the picture and abandoned if he doesn’t do something. When his mom mentions moving to Canada to start a new life, that seems to confirm the prediction, and Henry begins to wonder if he should turn Frank in. It all comes to a head when the race to get out of town is interrupted by the cops finding out where Frank is, and trying to stop him before he gets away.

The other day I was saying (like I always do) to stay away from the drama genre. Hollywood doesn’t like to make dramas. They not only have really low profit margins, but they have to be executed perfectly to work. The script has to be flawless, the acting has to be genius, the directing and the cinematography have to be awe-inspiring. They don’t have any margin for error because people only come to see these movies if they hear they’re great. Honestly, when’s the last time you said to a friend, “Let’s go see that drama movie that’s supposed to be okay!”

Every story needs an engine. And like I often discuss, the engine is often your hero’s goal (beat the terrorists, get to the beauty pageant, get the Americans out of Iran using a fake movie as cover). Even Flight, a drama I loathe, had a goal – to win the court case against the airline for pilot neglect. Labor Day bases its engine on something a lot harder to drive an entire story with – suspense. Suspense is something you typically use in doses, to drive a scene or a sequence. Using it to drive an entire movie is hard.

The suspense engine here is: “Will Frank, Adele, and Henry get away with this?” This is achieved by making us wonder whether Frank and Adele and Henry are going to ride off into the sunset and start a new life, or get caught. As far as I can tell, that’s the only thing driving the story.

That’s fine. A really well-told story CAN work this way. Here’s my problem though. For suspense to work, especially suspense that’s supposed to last the entirety of the movie, we have to freaking love the characters. And that’s where I had problems. The script is told through the eyes of Henry (in older Henry’s voice over). For that reason, we’re not watching the movie through the eyes of the two people who have the most to gain and lose here (Frank and Adele) but rather the character with the least to lose, Henry.

In addition to that, because we’re seeing two people fall in love through a third party, I never really felt those characters’ feelings. I never got close enough to them since I wasn’t allowed to see them unless it was through Henry’s perspective. It was kind of like watching two people kiss across the street instead of BEING one of the people kissing across the street.

Don’t get me wrong. I didn’t dislike any of these characters. I thought Henry was pretty interesting, Frank was pretty interesting, and Adele was pretty interesting. But “pretty interesting” doesn’t cut it when you’re making a drama. It’s not like The Avengers where a “pretty interesting” character is fine because you have 200 million dollars worth of special effects to fall back on. In dramas, THE CHARACTERS are the special effects. And for that reason they must be infinitely interesting, infinitely fascinating, infinitely compelling. After finishing Labor Day, I was just kind of like, “Ehh, not bad.” It was a nice little story. But that’s not enough for a drama. A drama has to be great.

Where could the script have improved? I think Eleanor should have had a much bigger part. She’s the love interest for the character we care most about, the one we’re closest to, Henry. Why do we get more time between two people we don’t really know than the actual person who’s leading us through this story?

If that could’ve been introduced earlier, and Eleanor could’ve found out about Frank earlier (in this draft, she doesn’t find out until the end), she could’ve pressed Henry to give Frank up sooner, lest he lose his mom to him, and there would’ve been a lot more conflict in the house, which as it stood was pretty conflict-free.

That was probably the biggest issue for me in the script. Frank’s situation was never really challenged. Outside of a couple of late characters dropping by, Frank could prance around worry free. And I’m not sure a movie like this works unless his situation is always in danger, unless we’re constantly feeling the possibility that he could be caught.

All in all, this draft of Labor Day had a slow story that lacked the kind of characters and conflict a drama like this needs. Hopefully, Reitman has sped the story up and addressed these issues in subsequent drafts. I admire the man for pushing stories in Hollywood that don’t usually get made, but the catch is those stories have to be awesome, and I don’t think this one’s there yet.

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Link up your story elements! I discussed this yesterday. Try and link up the elements of your story so they work together as opposed to separately. I thought Labor Day missed an easy one here. Henry was falling for Eleanor, who confesses sadly that she can no longer go to art school because her parents won’t pay for it (element 1). Later, Henry sees a “REWARD – $10,000” flyer for turning in Frank (element 2). Henry should be considering turning in Frank to get Eleanor the money so she can go to art school. That’s his main conflict. That’s what he’s battling every time he comes home. Should he call the police and run off with his own girl, or not call them and let Frank and Adele run off together?

Should you write the next Hurt Locker?

Should you write the next Hurt Locker?

So last week I went over the six types of scripts most likely to get you noticed. This week, my plan is depress the hell out of you and do the opposite. I’m going to give you the six types of scripts LEAST likely to get you noticed. And since I know there’s a portion of you probably writing one of these right now, you’ll likely want to castrate me. You’re going to scream-comment, “You’re wrong Carson! You don’t know anything!” And since I live in a country that protects one’s right to speak their mind, I’ll respect your opinion, even if I know it’s wrong.

Truth be told, since Scriptshadow is like a big warm blanket we’re all cuddling under, I don’t want everyone leaving here miserable. The only time I want people leaving the Scriptshadow Blanket is to sell their script. With that in mind, I’m going to offer you an alternative to these career-killing scripts. Think of them as food substitutions. Sure, we all love mayonnaise, but sometimes yogurt can do the trick. I know I’m not going to talk you out of everything, but if I can give you an alternative, maybe we can meet half-way.

Coming-of-Age script

Examples: Garden State, An Education, Beautiful Girls

Ahhh yes. It’s your early 20s. You’re recently out of school and confused about the giant unforgiving world. This leads to a malaise, a depression of sorts, a construct that makes you question the very worth of your everyday life. All you writers in your 30s are chuckling about now. You’ve written these before. Heck, we all have. An average looking main character with nothing going for him. He’s usually coming back to his childhood home. And of course he meets a really hot alternative girl who likes him for no other reason than the story needs her to and… well, you know the rest. Readers dread these scripts because their bosses would rather cut their eyes out than read them (yet they still have to do coverage) and they’re typically just a reason for the writer to complain about his life anyway. People rarely go to the theater to see this kind of film so the chances of one selling on the spec market is miniscule.

What you should do instead: Write a novel! The novel is much more accepting of this kind of story because instead of just seeing our protagonist look depressed for 50 scenes, you can actually write down what’s going on in his head, adding depth and context for why he’s so down on himself. Another option is to write a TV show! Shows like Girls prove that the coming-of-age genre can work in the 30-60 minute format.

Straight Drama

Examples: Winter’s Bone, Rust and Bone, The Words

I’ve already gone into depth on this site about why you don’t want to write dramas but it basically boils down to this. Almost all dramas that are produced are done so through pre-existing properties, mostly adaptations of books or articles. On the rare occasion that one isn’t, it’s usually a writer-director project. Studios tend to bust the straight drama out only when they want to win Academy Awards, and for that reason, only the best of the best writers are called in to pen these.

What you should do instead: Give us a hook! Look for some way to turn your boring straightforward drama into something more exciting. Life of Pi is about a kid stuck in the middle of the ocean with a hungry tiger. The Grey has men after a plane crash fighting off killer wolves. Midnight in Paris has time-travelling. Sure, you can write only about mundane everyday life, but I can almost guarantee you nobody’s going to buy your script if you do.

Fantasy/Sci-fi Fantasy

Examples: Avatar, John Carter, Percy Jackson and the Olympians: Lightning Thief

This kills a lot of writers. Because fantasy and sci-fi fantasy writers have got to be some of the most passionate writers out there. They love that they know all 49 planets in their dual-son solar system, Quazor. They love detailing every little inch of their weapons, like the Sword of Tagatu. They can probably tell you exactly what all 98 of their characters were doing 8 months ago to the day. But here’s the reality: There isn’t a genre readers hate more than this one. In fact, it’s easily the most made-fun of genre there is. Readers love trading stories about how fantasy writers teased their “quintology” at the end of their script. Or how they had seven moons surrounding the main world, three of which were alive. Do you really want to be the writer who readers make fun of?

What you should do instead: Write a self-published e-book. This is becoming an increasingly popular way to get noticed. More and more production companies and studios are buying up self-published books. And within these books, you have more room to get into all those fantastical eccentricities writers in this genre love. Scripts are more about action and energy and moving forward. They tend not to work when they’re bogged down by a million details.

The Sports Movie

Examples: Any Given Sunday, Goal!, Leatherheads

I love a good sports movie. But I learned early on that writing these things is a useless endeavor. You know what ruined it for us sports movie geeks? True stories. Unless it happened for real (Miracle, The Natural, Hoosiers), executives just don’t care because, let’s face it, there’s something a lot more exciting about an event that actually happened. Stay away from this genre unless you want to experience a lot of heartache and a lot of rejection.

What you should do instead: But wait! There are three things that can save you if you love sports so much you can’t write about anything else. First, find an article about an amazing true sports story and option it. That’s your best bet at selling a sports script. If not that, write a boxing/fighting movie. These can still sell if they’re not based on real life. If those two don’t work, write a sports comedy. Comedy is still the leading spec sale genre out there and sports lends itself perfectly to comedy.

An Animated Film

Examples: Hotel Transylvania, Brave, Paranorman

I’ve said it plenty of times before but nobody buys these. Every major animation department in town creates their stories in-house. And you know what? I never understood why. If someone comes up with a better animated movie idea than you, why wouldn’t you buy it? Unfortunately, not everything the studios do makes sense. I mean, someone decided to spend 280 million dollars on a Western. So don’t shoot me on this one. I’m just the messenger.

What you should do instead: A couple of things. Try to get jobs in any department you can at one of the big animation houses. People work their way up the ladder there all the time, many who started as interns. If you hope to ever write an animated film, you’re going to need a direct pipeline to the people who make them. Getting in the door is one of the only ways to do that. Save that, write a live-action script that’s light in nature, somewhat complex, funny, and that has a lot of heart. In other words, an animation film in a live action film’s body. Little Miss Sunshine by Michael Arndt is a perfect example. That’s the kind of movie that the animation houses notice.

A Contemporary War Film

Examples: The Hurt Locker, Green Zone

I keep getting sent these scripts and I keep trying to tell writers, you’re going to have a hell of a time trying to sell these. Contemporary war films just don’t make money because people don’t like to experience pain and suffering in the theater when they experience it every day in the news (for free!). And every producer knows this so every producer is wary of them. Take The Hurt Locker. Won an Oscar. Turned an unknown actor into a star. But it didn’t break 20 million dollars worldwide. Green Zone. Matt Damon, one of the biggest stars in the world. A movie shot similarly to his Bourne franchise. Nobody went to see it. Ditto for a war movie with another huge star in it: George Clooney in Men Who Stare At Goats. I could go on.

What you should do instead: If you must write about war, write a World War 2 film. There’s always an audience for those. Save that, find a GREAT original, unique, compelling, TRUE story with a hook. American Sniper just got Spielberg attached, and that’s because it’s based on a real soldier’s autobiography (that has a spoiler-ish hook to it which I won’t mention here). Still, I have doubts if that project will ever get made because, again, these movies just don’t make money.

There are other genre types I’d be wary of, but I’ll admit this. I have seen spec sale exceptions to every genre I listed above. I have seen people sell contemporary war scripts as well as straight dramas. The point of this article, though, is to steer you away from false hope. You’re already in an industry ruthless for how few people it lets through its doors. Writing in a genre that the industry never responds to is kind of like knowing your blind date hates sports and taking her to a baseball game. Sure, there’s a CHANCE it’ll be an amazing game and she’ll change her mind. But she probably won’t.

However, I know that writers are some of the most stubborn people on the planet. They love to prove people wrong. So if you’re going to ignore all this advice, let me offer up a couple of tips. First, if you’re going to write one of these scripts, make sure it’s because you’re beyond passionate about it. Make sure it’s because you can’t even conceive of writing anything else. And second, add SOME unique spin to it, something that makes your idea fresh. If it’s a contemporary war film, add time travel. If it’s an animated film, tell half the story in the real world. Do something unexpected and that just might be enough to make a producer bite.