Search Results for: 10 tips from

SCI-FI SHOWDOWN REMINDER

What: Sci-fi Showdown

When: Entries due by Thursday, September 16th, 11:59 PM Pacific Time

How: Include title, genre, logline, Why We Should Read, and a PDF of your script

Where: Carsonreeves3@gmail.com

In honor of Neil Blomkamp’s newest movie trailer and Sci-Fi Showdown, we are going back to one of the best science-fiction movies of the 21st century. Here’s what I wrote back in 2009 after I saw District 9: “Today, I went to see District 9. Even after all the hype, I still walked out amazed. We’re looking at the next James Cameron here. Sci-fi like this has never been done before. Within two minutes I actually believed this was happening – that aliens had landed on our planet.”

I think I may have invented the phrase, “This didn’t age well” with that take. It’s hard to put your finger on why Blomkamp fizzled. There’s no question he’s an insanely talented guy. I think part of the problem was that he never put as much effort into the mythology of his subsequent films as he did District 9. The guy is a director, through and through. But he’s never been a great writer.

District 9 feels like a dozen people sat around a room for a year and discussed every single detail about what this world would be like. You need that with science-fiction. You try to cut corners on mythology and your movie can go from deep to thin in a millisecond. We saw that with his follow-up film, Elysium, where you got the sense that Blomkamp wrote the script in a weekend.

But we still have District 9, which is a sci-fi classic. And Blomkamp is even talking about a District 10, which I’ll be first in line for. In honor of everything Blomkamp, here are 10 screenwriting tips from District 9!

1) The hunter becomes the hunted – One of the best ironic situations to place your hero in is to start him off as the hunter and then turn him into the hunted. Audiences LOOOOOOVE that. Why? Because everybody loves irony. To emphasize how effective this is, imagine if Wikus doesn’t work for the organization moving the prawns out of their homes. Imagine if he’s just some street food vendor who turns into an alien. It’s not nearly as exciting of an idea, is it? That’s the power of irony.

2) The Goal Before The Goal – A lot of writers make this mistake. They focus on the main character’s primary goal only. In this case, it’s for Wikus to figure out how to turn back into a human. But there’s often a period of time in your story before the main character is presented with a goal. In that case, if possible, you want to insert a goal BEFORE the goal. That way, your movie gets going right away. What Blomkamp does is he creates this storyline where South Africa has decided to move all of the aliens to a new location. This act of moving them creates a purpose for the story before our real plot begins.

3) Characters should always have something to do – When characters don’t have something to do, the story comes to a standstill. But it’s important to know the difference between the good something to do and the bad something to do. That difference lies in the goal being PLOT RELEVANT. A hero who’s going to get a coffee is NOT DOING ANYTHING. A hero meeting a hitman at the coffee shop to discuss killing his boss – THAT’S DOING SOMETHING. Whenever your character is doing something that’s pushing the plot forward, they’re doing something. Otherwise, nothing’s happening in your screenplay.

4) Don’t roll out the red carpet for your hero. Put up a barbed wire fence instead!!! – A classic beginner mistake is rolling out the red carpet for your hero’s interactions. Whatever he needs to do, it goes off without a hitch. It should be the opposite. You want to put up a barbed wire fence. Make it difficult. Especially in sci-fi movies where the stakes are high. Go and watch the sequence where Wikus tries to move the prawns from their homes. Literally every prawn gives him trouble. There isn’t a single house where the process goes smoothly. Fences create conflict. Red carpets create boredom.

5) Documentary/fiction hybrids are a cheat-code for exposition – One of the hardest things to do in sci-fi is manage all the exposition and convey it to the reader. Any sort of story with an interview component, such as a documentary, lets you bypass that. District 9 may be the most exposition heavy science fiction movie ever. But I bet you never thought about that until I just mentioned it. That’s because its exposition is hidden inside documentary interviews, so we never consider it exposition.

6) A line of suspense can add an extra level of intrigue to your story – All suspense is is hinting that something bad is going to happen in the future. You can use it, then, to increase the level of interest from the audience. All throughout the opening of District 9, we get these interviews of people talking about Wikus, but they’re doing so as if something terrible has happened to him. “Wikus was always such a kind boy,” his mother tells us. We now know that something bad is going to happen to Wikus, which increases our interest in sticking around. You could, of course, not have shown any of those interviews. But, by omitting them, you also omit a line of suspense that’s driving the reader’s interest.

7) Use language differences to create more interesting dialogue – All of the dialogue between Wikus and the aliens – whether he was trying to evict them or, later, when he’s asking them for help – was charged. It had a heightened unpredictable quality to it. I finally realized it was because Wikus never entirely understood the alien language. He grasped pieces of it, enough so that he could communicate with them. But because he couldn’t speak it fluently, he was always playing catch up. It was a major reason why all the scenes with him and the aliens were so good, that struggle to understand each other and the messiness that brings. I’m thinking you can do the same with any two characters who don’t speak the same language. You can use their misunderstandings and assumptions to create a more interesting interaction than if the two are able to communicate exactly what they’re thinking. Remember, with screenwriting, you’re always looking for ways to make things harder on the characters. Not being able to understand one another is a simple way to make things harder. And, as a bonus, it makes the dialogue better.

8) Your story’s theme and your main character’s flaw are almost always tied together – District 9’s theme is: don’t treat people differently just because they don’t look like you. And Wickus’s flaw is that he doesn’t treat the aliens like real “people” because he doesn’t see the aliens as real “people.” We see this when he’s tossing cat food at them and talking to them like babies. Only when he becomes an alien and sees others treating him the same way he treated the aliens, does he realize his mistake and change.

9) What’s the worst thing you can do to your character right now? – This is a great question that can lead to some great moments in your script. It’s not something you want to use in every scene. But it’s definitely something you want to use occasionally. When Wikus gets home after his long day at work where he’s ingested some strange chemical and has been throwing up the rest of the day, feeling sicker and sicker by the minute, Blomkamp could’ve easily had his wife waiting for him, notice that he’s acting strange, ask him what’s wrong. But that would’ve been a forgettable scene. Instead, Blomkamp asks, “What’s the worst thing I can do to Wikus right now?” And the answer was… give him a surprise birthday party! All Wikus wants to do is rest. He’s sick and getting sicker by the minute. Instead, he has to be happy and peppy and act like nothing’s wrong for the next couple of hours – his worst nightmare.

10) 99% of thriller scripts fall apart when they devolve into an “on the run” story – This is because most scripts go from a STRUCTURED STORY to, all of a sudden, the main character is running around like a chicken with his head cut off, his only goal to stay a step ahead of the bad guys. This trope is boring to watch because all ‘on the run’ stuff feels the same. To combat this, give your character targeted clear goals they’re trying to accomplish. These goals will bring structure back into the story and give it purpose. You can have them run for a few scenes. But then it’s time for them to come up with a plan. Wikus goes back into the Prawn Camp because it’s the only place where he can hide from the authorities. He then agrees to help the alien get his ship operational with the understanding that, when he does, he’ll turn Wikus back into a human. This is a way more interesting storyline than had Wikus just run around Johannesburg for two hours.

Hold on. Don’t tell me you’re sending your script out there without getting professional feedback first. You only get one shot with these industry contacts, my friend. Don’t screw it up by sending them the 10,000th average screenplay they’ve read this year! I do consultations on everything from loglines ($25) to treatments ($100) to pilots ($399) to features ($499). E-mail me at carsonreeves1@gmail.com if you’re interested. Use code phrase ‘WARM IN JULY’ and I’ll take a hundred bucks off a pilot or feature consultation. As long as you pay in July, you can send the script to me whenever it’s finished. Chat soon!

We’re keeping it going with Sci-Fi Showdown inspired Thursday articles. Remember, the Sci-Fi Showdown deadline is Thursday, September 16th. You can learn more about it here. It’s absolutely free. So get those sci-fi scripts finished and get them in on time. Let’s make a f%$#ing great science-fiction movie together!

One thing I want to point out before I get to today’s tips. A lot of these tips deal with the chase aspect of the film. But these tips can work for ANY type of chase. A car chase. A foot chase. An across-the-galaxy chase. They can also work within chase sequences. So if your script just has one chase sequence, these tips can be applied to that as well. All right. Let’s get to it.

1) 99% of Sci-Fi Movies require voice overs or a title card at the beginning of the movie to explain what’s going on – If you don’t need a ton of explanation to set up your movie, use a title card. If you’ve got a lot to explain, use a voice over. Fury Road uses Max’s voice over. Star Wars uses title cards. I don’t care which you use but you probably need one. If we don’t know how your world operates, we’re going to have a tough time enjoying what’s happening.

2) Urgency and Sci-Fi go together like peanut butter and jelly – The most underrated reason for Star Wars’s success – and I’m talking the original Star Wars here – is its urgency. Urgency can camouflage all sorts of script problems due to the fact that the story’s moving so fast, the reader doesn’t have time to notice problems. Fury Road doesn’t just embrace urgency. It makes it the driving force behind the entire story. The bad guys are always right behind them. There’s never time to slow down.

3) If you’ve got two protagonists, don’t let your first act get bogged down setting those protagonists up – Fury Road has two heroes, Max and Furiosa. Had they written this script traditionally, they would’ve spent the first 30 pages of the script setting both Max and Furiosa up before we went on the journey. Director George Miller knew that’d be a dumb idea in a movie built around urgency. So he chose to set one character up before the chase (Max) and the other character up during it (Furiosa). Too much setup can lead to boredom which is why saving some character setup for the journey might be a good option.

4) Why limit yourself to two sources of conflict when you can have three? – With one hero, you get internal conflict (the battle against one’s self) and external conflict (the battle against the antagonist). With two heroes, you get those things along with a third element of conflict – inter-relational conflict (the conflict that occurs between the two main characters). Since a good argument can be made that the more conflict there is in your story, the better, consider allowing two heroes to lead your movie instead of one, like Fury Road.

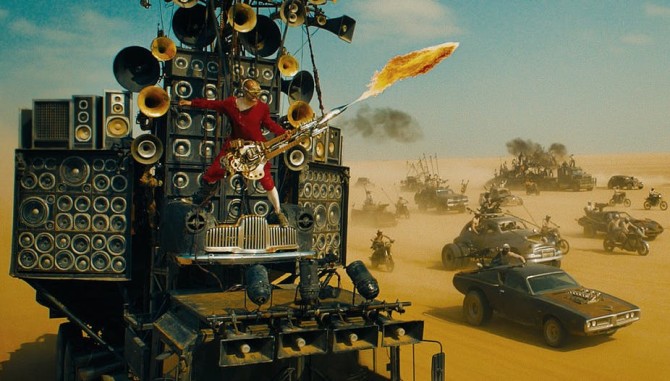

5) Your sci-fi movie *must* have original ideas! – If you’re not bringing any original ideas into your science-fiction film, don’t bother writing it. Sci-fi is a genre where a heavy expectation is placed on creativity and imagination. That means you’re going to have to take some risks and make some non-traditional choices. In Mad Max Fury Road, there is zero reason for Immortan Joe to create a big crazy theatrical chase team that consists of fireworks and dudes playing electric guitars on an 80 mile per hour stage to chase Furiosa. In fact, it’d be a hell out of a lot smarter to jump in your fastest cars and chase Furiosa that way. Yet that is exactly what separates this movie from every other sci-fi movie, is the theatrical nature of the chase. What choices will you make that set your sci-fi script apart?

6) In chase movies, you want to put your character in a lot of a situations where going forward is HARDER than surrendering – Too many screenwriters treat their on-the-run protagonists like little children that need to be coddled and helped. That’s the opposite of how you should treat your protagonists. You want to place your protagonists in situations where surrendering to the bad guys is the better choice. They famously did this in Empire Strikes Back when Han Solo decides to fly into a mine field to escape Darth Vadar, despite the fact that there was an infinitely higher chance he would die in the mine field. Same thing here. Furiosa sees the mother of all sandstorms ahead of her. Surrendering would be the better choice in this situation. Which is why we get so excited when she chooses to keep going.

7) Silent Characters work much better on screen than they do on the page – Mad Max in Fury Road, much like Mad Max in the original Road Warrior, doesn’t say a whole lot. While this can work great onscreen with a strong actor and strong director, it’s something I’d be wary about doing in a spec script. Unless your silent hero is EXTREMELY ACTIVE and always charging forward making bold choice after bold choice, he’ll likely disappear on the page. I’ve read lots of scripts with quiet protags and, I can promise you, those characters rarely make an impact. The difference with something like Fury Road is that the director is writing the script. So he doesn’t have to worry about any characters not working on the page as long as they work onscreen.

8) Fast movies need quick flashbacks – For the 217,000th time, don’t use flashbacks to begin with. But if you do, use them sparingly and with purpose (they must be necessary, not exposition-dumps). In action movies, you can use flashbacks, but do so in the spirit of the genre and be quick about it. Max has this backstory where he got a girl he was protecting killed. We get a good dozen flashbacks of this throughout the movie, but they’re very quick – 2 seconds or less. All that matters with backstories is that we understand them. So if we can understand them in 2 seconds, you’ve done your job.

9) – Mythology tends to work best when it operates in the background, not when you shine a big light on it and say, “Look at what I did.” – Science-fiction writers tend to love their mythology (the inner workings of their fictional world) so much that they constantly halt the movie so that their characters can talk about or exhibit aspects of that mythology (see Matrix: Reloaded). What’s so great about Mad Max Fury Road is that most of the mythology is background noise. There are these pale soldiers. They seem to have some sort of blood disease. They have their own language, their own chants. There’s a specific moment, during an intense part of the chase, where one of them sprays some crazy drug-foil all over his face, he screams out a well-known chant to the others, before leaping onto the enemy car with explosives, destroying it. There were so many little moments like that that only the pale soldiers understood – and Miller never stopped to explain all of it. It was always happening in the background.

10) Someone in your movie’s got to arc, dammit – Some serious directors and writers consider character arcs unrealistic. I just brought this up last week with Quentin Tarantino. You can see that in Fury Road in that both Max and Furiosa do not change. They do not arc. But you’ll also notice that Nux (the “War Kid” who originally would do anything for Immortan Joe) ultimately relinquishes his allegiance to him to help the rebel crew. Audiences like at least one character in a movie to go through some level of change. If you’re worried about a character flaw that would feel dumb or false for your heroes, know that you can use other characters in your movie to explore an arc as well.

Bonus Tip! – A great climactic set piece is all about making it look like there’s no way your heroes will win – It should never EVER feel like your heroes are doing well in a climax. You want the opposite to happen. Keep stacking the odds against them. Fury Road is a great example of this. When the protagonists are forced to go back through the bad guys to get away, there isn’t a single moment in that sequence where we think our heroes have a leg up on the bad guys. There are an endless amount of cars. As soon as one is taken out, another one takes its place. The bad guys are able to snag one of the girls. Max, on top of the truck, is barely holding off bad guy after bad guy. We feel positive that our heroes will fail. Which is exactly how you want it to be.

Dude, what are you doing!? You’re sending your script out without getting professional feedback first? You’re NOT getting help from someone who can tell you EXACTLY what’s missing and how to fix it? Why?? You only get one shot with these industry contacts. Don’t screw it up by sending them the 10,000th average screenplay they’ve read this year! I do consultations on everything from loglines ($25) to treatments ($100) to pilots ($399) to features ($499). E-mail me at carsonreeves1@gmail.com if you’re interested. Use code phrase ‘WARM IN JULY’ and I’ll take a hundred bucks off a pilot or feature consultation. Chat soon!

I listened to the entire 3 hour Joe Rogan interview with Quentin Tarantino yesterday and it’s an interesting listen for sure. Rogan isn’t much of a movie buff. Ironically, the only movies he seems to love are Tarantino’s. So the interview was more of a love fest from Rogan’s end and that prevented some of the more free-flowing conversation that you usually get from the podcast. Still, because it was Tarantino, there were lots of gems dropped. So many, in fact, that I thought I’d highlight the top 10 for you. I always learn something about screenwriting when Quentin speaks and this was no different. Let’s take a look.

1) Tarantino reads a lot of biographies – This may not seem like that big of a deal but it may be the most important tip on this list. I noticed, throughout the interview, that Tarantino kept referring to biographies he’d read. “I read this biography on So and So.” “Oh, I read her biography.” “Yeah, he’s got a great biography.” I’ve often wondered how Tarantino creates such vivid interesting characters. This may be his secret sauce. Biographies allow you to get into people’s heads in a way nothing else does. I’m sure, whether intentional or not, this is what allows Tarantino to access such incredible detail when he creates characters.

2) Go against the grain! – Tarantino points out that he grew up in a terrible era for movies – the 80s. Everything in the 80s was a correction of the avant-garde movies of the 70s. As a result, they were safe, they were friendly, they were politically correct. Tarantino responded to this with, “I don’t want to make those movies. I want to make something different.” Which is why his movies revolutionized the business. They were unlike any movies we’d seen. I want you to apply that mindset to the cinema of 2021. Are you writing movies that are just like the movies you’re seeing today? Or are you writing movies that you want to see? You can make both work. But the second option allows you to become a potential game-changer.

3) Let the character decide where the story goes, not the writer – This is a hard one for beginners to grasp because they look at their characters as fictional creations and therefore the idea of giving them creative autonomy is an assault on logic as well as their ego. But here’s why it’s a relevant philosophy. Screenwriters are too stringent. They’re trying to hit that first act break. They’re trying to shove in those Blake Snyder beats. Their intentions, much of the time, are in service to structure. If you see your characters as real people, their intentions will be much more pure. What they say and what they do is going to steer your story in a more unique direction. This explains why Quentin’s movies are so original. He doesn’t play God. He lets his characters play God.

4) But he gives himself an out – With that said, Tarantino gives himself an out. “I am the storyteller,” he says, “so if I have to steer [the characters] in a direction that I think is more interesting or more exciting, well then obviously I can do that. I have the power to do that. But I’m trying not do that.” In other words, this kind of rule works in theory but it doesn’t always work in practice. If characters are blathering away about something mundane or boring, it’s in your interest to reevaluate the scene and, possibly, steer it in a more interesting direction. Also, we’re talking about Quentin Tarantino here. His characters are so vivid and his imagination so active that his version of “letting characters take you where they want to go” is going to be more interesting than the average writer’s “let your characters take you where they want to go.” So don’t assume that following this advice is an automatic win. Sometimes you have to intervene.

5) Don’t be afraid to write uncomfortable moments – I already know this tip is going to trigger some people but it’s one of the things that sets Tarantino apart. Ever since that brutal torture scene in Reservoir Dogs, Quentin hasn’t been afraid to take on the PC Police. Here, Rogan brings up the scene in Hateful 8 where Jennifer Jason Leigh’s character gets brutally beaten and he basically asks Tarantino, “Is that okay?” considering it was a woman. Tarantino’s answer was that, of course it was okay. This was a really bad woman who had done really bad things. If she was a man and did the exact the same things, everyone would be fine with him getting beaten. So why should her gender matter? He acknowledged that it is tougher to watch. But that was the point. He wanted that moment to be uncomfortable. That was a deliberate artistic choice. This is a big reason why Tarantino’s movies feel so different. He’s comfortable with making people uncomfortable. So you can be the artist who stays between the lines and writes comfortable safe things. Or you can be the one who stands out.

6) Making a movie is easier than ever – Outside of maybe Robert Rodriquez and Kevin Smith, Quentin is the OG DIY filmmaker. When he got money in his bank account, his sole focus was to figure out how to use that money to make a film. He made 30 grand for writing True Romance and his first thought was, “I’m going to make Reservoir Dogs with that money.” You have to understand back in 1991 just how insane of an idea making a movie for 30 thousand dollars was. Just the cost of film processing alone was probably 30 grand. But the mindset back then was: FIGURE IT OUT. Do whatever you have to do to get your movie made. It just so happened that a producer was able to raise a million bucks for Tarantino to make Reservoir Dogs. But he would’ve made it for 30 grand if he had to. I bring this up because the barrier for entry to make a movie in 2021 compared to 1991 is 10 times lower, AT LEAST. Yet people seem to have more excuses than ever why they can’t make a film. I know not every screenwriter wants to be a director. But if you’re interested in directing at all, channel that original Tarantino spirit of getting your movie made no matter what. It’s still the fastest way into the business.

7) Quentin’s writer’s block advice – Tarantino’s process works like this. He’ll write a scene and, if he doesn’t finish the scene, he’ll get away from his writing pad (he still writes longhand), and just think about the scene in terms of what could make it better and where it could go next, and then he goes back to his pad, jots down all those notes and then he DOESN’T WRITE IT. He waits until the next day to implement that stuff. If he *does* finish a scene, he utilizes this same process but focuses more on the next scene and where that scene could go. Afterwards, he writes down notes and calls it a day. This way, he’s always going into tomorrow’s writing session with momentum. Cause he’s always got something prepped to write.

8) Audiences need someone to root for, even in Tarantino movies – One of Tarantino’s least successful films is Hateful 8 (by the way, this is one of my favorite Tarantino films). He recognized, after reading criticisms of the movie, that he made a choice the movie couldn’t overcome, which was that every character was a villain (that’s why it’s called the “hateful” 8). And while he personally loves the movie, he learned that making a film without anybody to root for isn’t the best way to go. Although he doesn’t say this in the interview, this may have been why he followed that movie up with one of his most likable characters ever in Once Upon A Time In Hollywood’s Cliff Booth (Brad Pitt).

9) You can’t spell Tarantino without “fun” – What I’m about to tell you is something I don’t think even Tarantino realizes about his movies. Tarantino talks all the time about violent films that inspired him. He talks about “Manhunt,” “Taxi Driver,” “Mean Streets,” “A Million Ways To Die.” But those movies never touched the popularity or the box office of a Tarantino movie. And I think the reason for that is is because Tarantino likes to have fun in his movies. No matter how dark or violent his movies get, they have tons of jokes, they have tons of fun moments, they have tons of entertaining dialogue. What he’s done is basically figure out how to popularize dark cinema. He’s made it fun. I’m not saying you have to do this. But if you’re writing something dark and you want to broaden your audience (aka, get more producers interested), consider doing what Tarantino does and add those fun moments, those jokes, that dialogue.

10) Tarantino doesn’t like character arcs – Listening to Tarantino talk, you get a sense of his disdain for movies that have heroes who act one way for 70 minutes, only to completely change into a nicer more wholesome person for the final 30 minutes. You can tell he doesn’t buy it. He doesn’t see any authenticity in it. And if you look at his last movie, you can see that none of the three main characters, Rick Dalton, Cliff Booth, or Sharon Tate, change in the movie. They’re the exact same people at the end. To be honest, I don’t know what to make of this belief. I understand that artificially forcing a character transformation at the end of the movie is weak sauce. But it’s tough to sell characters who don’t learn anything at all over the course of their journey. There’s an element of “well then what was the point?” to the viewing experience. I’m not sure I agree with Tarantino’s take here. But, again, this is one of the many rules he lives by that makes his movies feel different from everybody else’s.

Don’t write a single paragraph in your script that’s more than three lines long – You are writing a spec script and you are an unknown screenwriter. Those two things equal an impatient reader. Never give them an excuse to give up on your script. Keep the action lean so the eyes fly down the page.

Cut out 50% of your backstory – We tend to think the audience needs more information about the hero’s past than they do. Only include the BARE MINIMUM of backstory and not a word more. Have you ever heard of a movie called Chinatown? Won a few awards. Considered by some to be the best screenplay ever. Did you know that in the original script there was this big long monologue from Jake (the main character) about this terrible thing that happened to him in Chinatown? But, ultimately, Robert Towne realized it wasn’t important for anybody to know. So he cut it. If the monologue that explains why a movie is titled what it is can be cut, you can certainly ditch all the excess backstory in your script.

Give your three biggest characters AMAZING IMPOSSIBLE TO FORGET introductions – I’ve read so many scripts where I’ve forgotten the second or third biggest character in the script. And when I go back in the script to figure out why I forgot them, it’s almost always because they had a weak introduction. It should go without saying that your hero needs a big memorable introduction. But it’s also the case for your second and third biggest characters. Don’t introduce them as, “Brenda, 25, bright and fun” and then have them say two lines in the scene. Give them an action or a difficult choice or a monologue or SOMETHING that makes them instantly memorable. Go check out Clementine’s introduction on the train in Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind. Tell me you don’t remember that character instantly.

Either your villain or your hero needs to be pushing the story forward – If any other characters are pushing the story forward, you’re probably doing it wrong. You want to either put the plot on your hero’s back, meaning he’s carrying the plot forward (Arrival – Decode the alien’s language) or the villain’s back, meaning he’s trying to accomplish something (The Invisible Man – the dead husband attempts to drive his ex-wife insane). Often in movies, it’s the villain who will carry the plot initially (Darth Vader in Star Wars – retrieve the stolen Death Star plans) and, at some point, the hero will be the primary carrier (Luke is determined to save the princess and, eventually, blow up the Death Star).

In a key scene, write your hero into a corner that even you don’t know how to get them out of – I can’t stress this one enough. Too many writers write their heroes into “difficult situations” that aren’t difficult at all because they knew how they were going to get the character out of the problem from the get-go. If you already know how to get them out of the problem, chances are the reader does as well. You want the opposite effect. You want the reader to think, “How the hell are they going to get out of this pickle?” If you don’t know, they won’t know. Yes, it’s harder to figure out how to get them out of that pickle. But nobody said writing was easy.

Give your scenes a beginning, middle, and end – Too many writers these days rush through scenes, creating scene fragments. Treat each scene like its own little mini-movie, even if it’s short. Give it a setup (character goal), some conflict (something gets in the way of the goal), and a resolution (they either succeed or fail at obtaining the goal). So, for example, maybe a cop is trying to extract information out of a witness to a murder. That’s the goal: to get the information. However, as soon as he starts asking questions, the witness is worried about incriminating herself. She wonders out loud if she should have a lawyer present. The cop assures her that they’re just talking. Nothing she says is going to get her in trouble. But now she’s on guard, not as open (conflict!). Finally, the cop either gets her to give him the information or fails. The scene is over.

Eliminate AS MANY ACTION LINES BETWEEN DIALOGUE LINES as is humanly possible – Readers love uninterrupted dialogue. They hate when Joe says something to Jane, then you tell them that Joe lights a cigarette, then you have Jane respond. “But Carson. What if it’s important to show that he lights the cigarette?” Nobody cares if your character is smoking a cigarette. The exception would be if the cigarette plays into the scene later, such as it accidentally starts a fire. If you must tell them, tell them before the dialogue begins, not during. And this goes for any ultimately unimportant action.

Eliminate every single dialogue line where your character is talking directly to the reader – For example, if it’s important that the audience know that the hero’s mother is dead, don’t have them say, “That reminds me of when my mother died. I still don’t know if I’m over it.” Look for another solution. Maybe your hero saved his mother’s last voicemail to him and he plays it whenever he misses her. “Hey Brett, it’s me. Just checking to make sure you and Liz are still coming for dinner tonight. Dad’s looking forward to meeting her. Love you. Bye.”

As the rewriting process goes on, place heavy emphasis on the third act – Whenever we write a script, we prioritize the first act. We rewrite it over and over and over again because it’s the first thing we see when we open the script. Meanwhile, our final act gets neglected. Technically speaking, your final act is usually 4-5 drafts behind your first act because you haven’t spent nearly as much time on it. So stop obsessing over making those first few scenes perfect and spend that time getting your third act up to speed. It almost always has catching up to do.

And the hardest tip of all….

Hold yourself to a higher standard with every single scene – Grade every scene in your script HONESTLY on a scale of 1-10. Do not show anybody your script until every scene is at least a 7. Preferably, it should be an 8 or higher. If you hear yourself thinking stuff like, “But this is just a normal scene to get my hero from A to B. It’s not meant to be special.” That’s a good sign you either need to get rid of the scene or rewrite it. You want every single scene to be entertaining. For reference, the average scene I read from an amateur screenwriter is a 4. The scenes aren’t unique or entertaining at all. They’re just moving the story along without the drama required to keep the reader engaged.

Today we’re covering a movie that would NEVER get made today. But, not to worry, I think it’s only a matter of time before the pendulum swings back to sanity with this cancel culture stuff. Comedy is at its best when it’s pushing the envelope. And today’s script shows us just how hilarious pushing the envelope can be. If you’ve never seen Tropic Thunder, it’s about a group of actors shooting a war movie who, unknowingly, find themselves in an actual war.

1) Easy comedy concepts are staring you in the face! – Further proof that one of the easiest ways to come up with a funny movie idea is to take a serious movie and turn it into a comedy. “What if we made Platoon a comedy?” could’ve easily been the starting point for this concept.

2) Character intros that tell you exactly who your characters are – Introduce your characters in a way that tells us exactly who they are. Comedies are about LAUGHS so you don’t have 20 minutes to meticulously set a character up. You gotta do it quickly so you can get to the funnies. To this day, no comedy has set up its characters better and faster than Tropic Thunder. The idea to introduce each character via trailers of the biggest movie they starred in (Tugg Speedman in his goofy blockbuster franchise, Scorcher. Kirk Lazarus in his Oscar bait gay priest movie, Satan’s Alley. And Jeff Portnoy’s awful ‘plays all the characters in the movie’ Fatties franchise) immediately told us who these characters were.

3) Every situation is an opportunity for a character to reinforce his funniest trait – The joke with Kirk Lazarus (Robert Downey Jr.) is that he’s always trying to win an Oscar with every line he delivers. So when Tropic Thunder’s director gets blown up by a land mine, the five actors look around at each other, unsure if what just happened was real or fake. Tugg Speedman (Ben Stiller) declares, “This is nothing, guys. It’s all part of the game. It’s what he was talking about with all that ‘Playing God’ stuff.” Kirk Lazarus looks off at nothing and, in the most serious voice you can possibly imagine, replies, “He ain’t playing God…. He’s being judged by him.” Lazarus dutifully delivers Oscar-baiting lines even when their director just got blown to bits.

4) Death is hilarious – In every other genre, death is serious. But comedy is the one time people are willing to laugh at death. So take advantage of that. When the director is blown up by the mine, Tugg Speedman is convinced it’s fake. He assures the guys, “I’ve been in a lot of special effects movies. I think I know what a prosthetic head looks like.” Tugg picks up the director’s head and starts playing with it, going to every extreme to prove it’s fake, even tasting the blood to prove it’s corn syrup. Death is funny guys. Lean into it!

5) Never let a busy plot get in the way of your comedy script – I have seen busy plots destroy comedies. Busy plots lead to lots of exposition. Exposition is hard to make funny. Tropic Thunder doesn’t do a great job of this. There are quite a few scenes where the characters have to stop and remind themselves where they’re going and what their current goal is. There’s a boring scene, for example, where they realize they mis-followed the map and are now lost and they have to figure out where to go next. Too many of these scenes can disrupt the rhythm of your comedy, which is when readers start losing interest. Try to keep your plot as light as possible in a comedy. And if you are adding big plot points, make sure they’re funny!

6) Ultra-serious guy is funny! – A standby character that’s almost always funny is the SUPER EXTREMELY SERIOUS GUY. This character always works because of the irony. What’s the polar opposite of funny? Serious. So when you dial that up to 11 in a comedy, it rarely misfires. In Tropic Thunder, that character is Nick Nolte’s Four Leaf Tayback, the real life veteran who wrote the book the movie is based on. Nolte steals many of the scenes he’s in with his deadly serious delivery. When explosions expert Cody (Danny McBride) informs Four Leaf he’s his biggest fan and tries to chum it up by asking, “That’s a pretty cool sidearm you got there. What is it?” Four Leaf replies… “I don’t know what it’s called. (Long pause) I just know the sound it makes (long pause) when it takes a man’s life.”

7) Learning proper structure puts you in rare air in the comedy genre! – I’ll let co-writer Justin Thereoux explain why: “Me and Ben had written a bunch of scenes. Basically, we beat out the characters, and had sixty pages of loose stuff that we were trying to organize. But Ben was working and I was working, so we called Etan (Cohen), and he came in, gave us an outline, and wrote a short draft. Then me and Etan worked together in L.A. I came out from New York, and we hung out for an intense five days where we went through the script and recalibrated the tone. Then he went off, and me and Ben took the script and [finished it].” Comedy people actually aren’t very good with structure I’ve found. They’re good at jokes. They’re good at coming up with funny situations. But I can’t tell you how many comedies I read where the structure is a mess. Heck, even yesterday’s script had structure problems. If you’re funny AND you’re good with structure? You’re the total package, baby.

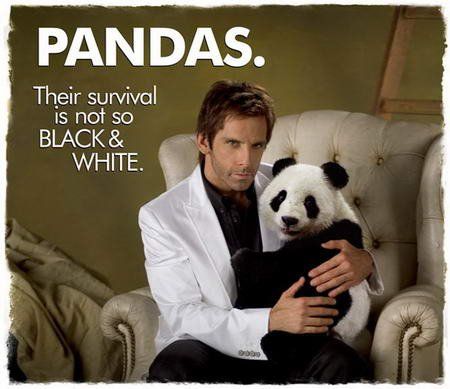

8) To give the audience what they ‘expect’ in a comedy is the equivalent of script suicide – You want to avoid the expected in every genre, of course. But you especially want to avoid it in comedy because the best punchlines are often unexpected. Tugg Speedman is alone in the jungle at night when he’s attacked by a large animal. Blinded and desperate, Speedman grabs his knife and releases his inner rage, battling the animal, stabbing it dozens of times. When he finally kills it and is able to see what it is, what do you think he finds? A bear? A jaguar? A tiger? No. It’s a panda bear. Tugg killed a cute cuddly panda bear.

9) Comedies are upside-down world – In comedy, insignificant things are often extremely important and extremely important things are often insignificant. For example, one of the major running jokes in Tropic Thunder is Tugg Speedman’s agent (played by Matthew McConaughey) becoming obsessed over a minor clause in Speedman’s contract – he gets to have Tivo on location – not being met. McConaughey’s entire storyline is built around him making sure that somebody corrects this mistake. It’s hilarious because, in the grand scheme of what’s happening, it is beyond insignificant.

10) Likability of your main character matters a lot in comedy – In a Collider interview, Ben Stiller (who directed and co-wrote the film) was asked if he was worried about Tugg Speedman being unlikable in the script. This was his answer, “Sure, there were aspects of my character in the beginning that I put on the DVD, the extended cut because at that point, who cares if we’re likable or not? (Laughs.) Um, but that was one of the things, because my character is trying to adopt a baby and there’s a joke where he said, ‘I feel like all the good ones are taken.’ And it was always funny out of context, but in the movie it always felt like people thought, ‘Ugh, I don’t want to watch that guy for the rest of the movie.’ (Laughs.) So, I cut that from the movie.” While it’s tempting to have your hero say whatever jokes pop up in that head of yours, you need to be more calculated. Sometimes an early hateful or off-color joke can solidify a character as “unlikable” in the audience’s mind. So be mindful of that. Also, when you have people read your comedy, one of the first things you should ask them is, “Did you like my main character?” If they didn’t, ask why, and try to correct it.