Search Results for: 10 tips from

Hello everyone. First of all, I want to thank everybody who congratulated me on the New York Times article. I’m hosting a friend this week and therefore haven’t really had the time to process it all. It’s funny because I don’t read the New York Times. And you know how even if something is huge, if it’s not a part of your personal day to day life, you don’t hold it in the same high regard as everyone else? So, as crazy as it sounds, I didn’t think much of it. But then when all my New York friends and older friends and family (my older brethren have read the Times forever) found out, they were all like, “This is a really huge deal!” I was like, “It is?” So it’s hitting me a little harder this morning than it did over the weekend and now that it’s settling in, I’m very thankful for it. And once again, it wouldn’t have been possible without all of your support. So thank you to everyone who reads Scriptshadow, even the haters! This would not be possible without you.

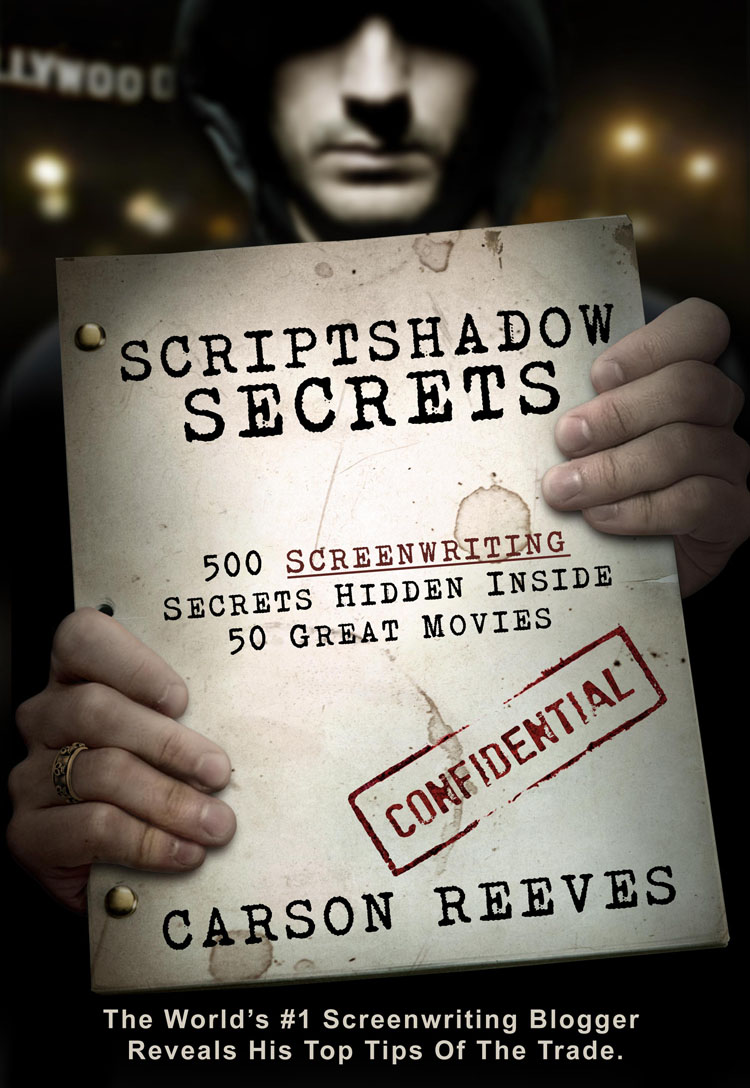

Now, this week is going to be a little different. Why? Because it’s SCRIPTSHADOW BOOK RELEASE WEEK!!! Some of you may have noticed that the book ad on the upper right-hand side has been changed from “Coming Soon” to “Buy now.” You can click that picture or click right here and you’ll be taken to Amazon where you can buy a copy of the e-book. Many of you have been asking me, “When can I get the book in physical form?” Unfortunately, paperback copies of the book won’t be available for another 1-2 months. We’ll get there. It’s just going to take some time.

So what’s the book about? Well, I basically took the most popular aspect of the site – the “What I learned” section – and applied that philosophy to an entire book. So I took movies like Raiders of The Lost Ark, The Social Network, and The 40 Year-Old Virgin (50 movies in all) and broke down 10 things I learned from each, which translates into 500 screenwriting lessons/tips/tools. I also wrote the book because that’s how I personally learn best, through example, so I always wished there had been a screenwriting book out there that taught solely through example. Well, now there is!

Now for those pounding your fists due to the fact that there will be no reviews this week, hold tight. This is Scriptshadow. I can’t go through an entire week without reviewing SOMETHING. So Wednesday is going to be realllly special. I’m reviewing 300 Years! This is a script I found from an unknown writer up in San Francisco named Peter Hirschmann, who’s not only super talented, but a really great guy. I loved the script so much, I asked to come on as producer, and we’re currently doing a rewrite before we go out to directors. In the spirit of Scriptshadow, I would LOVE to hear your feedback on it. There are a couple of places we feel it can be improved, so we’re open to ideas. If you want to read it, contact me at carsonreeves1@gmail.com with the subject line “300 YEARS.”

And now, it’s time. The following is a small excerpt from the first chapter of my book, “Scriptshadow Secrets,” available in E-book format from Amazon. This opening section prepares you for the movie-tip section by introducing the basics of writing a screenplay. Tomorrow, we’ll delve into some actual tips. Enjoy! (p.s. Because I’m performing hosting duties all week, I’m not going to be as quick with moderation. So, sorry if your comment gets stuck. I will do my best to get them up as soon as possible).

Excerpt from Scriptshadow Secrets…

(edit: People have been asking if they need an ipad or Kindle to read the book. The answer is no. You just need to download the Kindle Reader to your PC and you can read it right from your computer. Download the Kindle App here).

STRUCTURE

Whenever you write a screenplay, you’re telling a story. A lot of writers forget this, and it’s funny because we tell stories every day. When you have a few beers with your buddies and share how you asked the intern out? You’re telling a story! When you replay the amazing three-run homer your son hit at T-ball? You’re telling a story! When you’re giving your professor an excuse for why you didn’t finish your homework? You’re telling a story! A screenplay is just another venue to tell a story.

In order to tell an entertaining story, though, one that’s going to keep your audience on the edge of their seats, you need to understand structure. Structure places the key moments of your story in the spots where they’ll create the most dramatic impact. Ignore structure, and your story will have no rhythm, no balance. It might be front-loaded or back-loaded, choppy or unfocused. For example, in the story about your son’s three-run homer, if you jump straight to the home run, your story will be short and anti-climactic. With good structure, you set the stage for that home run over time, leading to an exciting climax.

The structure you’ll be using for almost all of your scripts is the 3-Act Structure. Don’t be intimidated by its fancy moniker. All it means is that there are three phases to your story: a “Beginning,” a “Middle,” and an “End.” Or, if you want to take the training wheels off, a “Setup,” some “Conflict,” and a “Resolution.” If you’re going to write screenplays, then you’ll be writing 90-120 pages of story contained within this basic 3-Act format.

ACT 1 (20-30 pages long)

Act 1 sets up your hero and then throws a problem at him. That problem will propel him into the heart of the story. Let’s say our story is about a guy desperate to ask out a beautiful intern who works at his office. To start your story, you might show your hero staring longingly at the intern from afar. He may even text his buddy: “No more messing around. I’m asking her to the Christmas party this weekend!” Soon after, you’ll write what most screenwriters refer to as the “inciting incident,” which is a fancy way of saying, the “problem.” A great example of an inciting incident happens in the movie Shrek, when the fairy tale creatures move into Shrek’s swamp. This is the “problem” to which Shrek needs to find a solution. In our story, it might be when our office dude learns that it’s the intern’s last day at work! In other words, this is his last chance to ask her out!

This inevitably leads to our hero having to make a choice. Does he stick with his old life (never taking any chances) or man up and go for the goal (ask her out)? Well, we wouldn’t have a movie if the hero stayed put, so your character always goes after the goal. In Shrek, this moment occurs when Lord Farquand tells Shrek that if he rescues the princess, he can have his swamp back. In our office story, it might be as simple as Office Dude deciding he’s going to ask Gorgeous Intern out today. He knows she always makes copies at 11 o’clock. So he spiffs himself up and heads to the copier room.

ACT 2 (50-60 pages long)

A lot of people get confused by Act 2, so let me remind you of its nickname: “Conflict.” Act 2 is the act where all the resistance happens in your story. Your hero will encounter arguments, setbacks, physical battles, insecurities, broken relationships, obstacles, their past, the protective best friend, killers, guns, car chases, and 80-foot lizards – basically, anything that makes it harder for them to achieve their goal. The more things you throw at your character, the more conflict he’ll experience. And conflict is what makes your story fun to read!

In addition to this, every roadblock, every obstacle, every setback, should escalate in difficulty. Start small and keep building. In our office story, maybe our office character stops outside the copy room, takes a deep breath, checks his reflection in the window, practices the big question a couple of times, then opens the door. He finds Gorgeous Intern, but, lo and behold, she’s talking to Sammy the Office Stud, who has her doubled over with laughter. Oh snap! Obstacle encountered!

Pages 55-60 in your script are referred to as the “mid-point.” The mid-point is important because it’s where your story changes direction. Whatever the first half of your story was about, the mid-point will shift it in a slightly different direction. By doing this, you keep the story fresh. So in our office story, maybe the midpoint is the fire alarm going off, forcing everybody to evacuate the building. This will place the second half of your story in a new environment – outside. If you want to use a real movie example, the midpoint of The Godfather is when Michael kills the Captain and Sollozzo at the restaurant. There are a million different scenarios you can write for your mid-point, but something needs to happen to give the second-half of your screenplay a slightly different feel from the first-half. Otherwise, the reader will get borrrrrrr-ed.

The pages after the mid-point and before the third act, form what I call the “Screenwriting Bermuda Triangle.” It’s where most screenplays go to die. What often happens is that writers run out of ideas in the second act and start scribbling down a bunch of filler scenes until they can get to the climax. Filler scenes are script-killers and will destroy everything you’ve worked so hard for.

If you follow proper structure, however, you should be able to navigate the Bermuda Triangle. After the mid-point, keep upping the stakes of your story. Make the problems bigger and more difficult for your character. In our office story, maybe it’s freezing outside, so everyone is pissed-off when the fire alarm sounds. To make things worse, the gorgeous intern is now cuddling up with Sammy the Office Stud to stay warm. That’s when the boss hits us with a bombshell: if they can’t get back inside within the next 20 minutes, he’s calling it a day. Ahhhh! Our hero now has 20 minutes to ask Gorgeous Intern out or lose her forever!

As the pages tick away in this section, so too should the attainability of your character’s goal. The closer we get to the climax, the more dim your hero’s chances of achieving his goal should get. In our office story, perhaps a car splashes water over our hero’s suit, destroying his appearance. Or even worse, a rumor spreads that the company is downsizing next week and his job is on the chopping block. It looks like all hope is lost. This is often referred to as your hero’s lowest point and will signify the end of the second act. We might even see Sammy the Office Stud nudge Gorgeous Intern towards his car where they can “warm up,” as our hero watches on hopelessly .

ACT 3 (20-30 pages)

The final act of your screenplay is really about your hero’s inner transformation, which is complicated, so we’ll discuss it later in more detail. In short, after your hero reaches his “lowest point,” he’ll experience a rebirth, finally realizing the error of his ways. If he’s selfish, he’ll see the value of selflessness. If he’s fearful, he’ll find the strength to be brave. He won’t have completely transformed yet, but this realization will give him the confidence to go after the girl or take on the villain or look for the treasure one last time.

In our office story, our hero realizes that his whole life has been a series of missed opportunities because he’s been afraid to take chances. I call this the “epiphany moment” and it signifies that your hero is ready to take action. Our office hero straightens up, barges through the group, CHARGES after Gorgeous Intern, spins her around, and plants a big wet one on her. She, Sammy the Office Stud, and all the coworkers stare at our hero in shock. He can’t believe it either. He’s done it! He’s won over the girl of his dreams! That is, until – CRACK – a hand smacks him across the face. “Asshole!” the intern shouts, grabbing Sammy the Office Stud and stomping off. Our hero stands there, alone, and watches her leave. The End. Hey, I never said this story had a happy ending!

Now, it’s important to remember that this is the most basic way to tell a story: a beginning, a middle, and an end. But as you’ll see over the course of this book, movies have taken this basic template and mutated it into hundreds of different variations. For example, there are movies where the hero doesn’t have a goal. There are movies where the story’s told out of order. There are movies where there isn’t a traditional main character. These are all advanced techniques and before you attempt them, you need to know the basics. We’ve just reviewed the basics of structure. Now let’s take a look at the basics of storytelling.

I was a terrible screenwriter. I once wrote a script about a man who was half-llama. I’m not kidding. The most frustrating thing about my failure was I didn’t know what I was doing wrong. It was obviously something, but after reading all the screenwriting books, hunting down all the screenwriter interviews, and writing until my fingers bled, there was still a big piece of the equation missing. I just couldn’t figure out what it was.

A friend of mine who’d been telling me to read scripts forever finally stuffed one in my face and told me he wasn’t leaving until I finished it. It was one of those “six figure sales” that gets splashed all over the trades. I opened the script begrudgingly, preparing to be bored out of my mind, and instead had as close to a religious experience as a writer can have. Something clicked while reading that script. Screenwriting made sense to me for the first time in my life.

I began scarfing down every screenplay I could find, often digesting three or four in a single sitting. At my most insane, I was reading 56 screenplays a week (eight a day!!!). This religious learning experience was so powerful, I began formulating a plan to introduce it to aspiring screenwriters. What if I reviewed professional screenplays online, helping amateur writers learn directly from those who’d already made it? It seemed obvious. Scriptshadow was born.

To my amazement, the site gained an immediate following and quickly became one of the most popular screenwriting sites on the internet. It has since been featured in numerous publications, including Wired, The New York Times, and the Wall Street Journal. It’s exceeded my expectations on every level and its success has allowed me many opportunities I had only dreamed of a few years earlier.

The structure of the site has evolved over time. I used to only review scripts, but now I mix it up. Monday is typically a screenplay-centric breakdown of the latest big movie. Tuesday I take a well-known film and extract 10 screenwriting tips from it. Wednesday I typically review a feature script or a television pilot. Thursday I write an article. And Friday, I turn it over to you guys, reviewing an amateur script. What’s been really exciting is finding some great amateur scripts in that Friday slot and those scripts go on to either sell or get the writers representation.

At the top of the site, you’ll see a toolbar for everything else. We have the best script consultants on the web in the “Script Notes” section, available at every budget to get your latest screenplay into shape. We have artists in the “Concept Artists” section to help you create concept art or one-sheets to stand out when pitching or querying. We have “Amateur Friday,” where you can submit your script for one of those coveted Friday reviews. We have one of the best screenwriting communities on the web in the comments section. No bitter angry dudes here. Just writers helping other writers out. And finally there’s the Scriptshadow book, which has 500 of the best screenwriting tips you’ll find, all broken down with examples from classic movies.

If you’re a big fan of the site (only big fans apply!), you should definitely get involved in the newsletter. I send it out once a week. It covers the big sales of the week and I review one of the bigger screenplays floating around Hollywood. It’ll be one of the only newsletters you’ll actually look forward to.

Hope you enjoy the site and if you have any questions, e-mail me at carsonreeves1@gmail.com!

One thing I believe I’ve done a fairly good job of on the site is reinforce the value of structure. You guys understand the inciting incident. You understand where the first act turn needs to be. You understand goals, stakes, and urgency. Some of the more advanced writers understand obstacles and conflict. All of these things are going to give you, at the very least, a solid screenplay.

But lately, I’ve been running into a lot of screenplays that do all of these things, yet are still boring.

You’d think that if somebody executed my precious GSU, I’d be preparing a 5 course meal of praise for them. But as wonderful as my darling little GSU is, it can’t make up for a crater-sized emotional void in a screenplay. And there are more craters in these scripts than there are on a full moon. They leave me feeling…empty. They don’t connect in some way.

A while back I wrote an article about the 13 things that every screenplay should have. At the end of that article, I talked about something called the “X-Factor.” The X factor is that indefinable thing that elevates a script above the pile. It’s that special sauce that makes all the pieces melt together. I call it the X-Factor because it’s hard to quantify. Something feels exciting and fresh and charged about the screenplay, but you can’t put your finger on what it is.

I believe I’ve finally figured out what it is.

SOUL.

These well-executed but boring screenplays don’t have any soul. All of the elements are where they’re supposed to be. But it’s the difference between a human being and a robot. You can feel a human being’s presence, the life beating out of them. The robot may look human, may even act human, but he emits no emotion, no love, no SOUL. So as neat as a human-looking robot is, you’ll never be able to connect with him.

So I set about trying to figure out the impossible: How to quantify SOUL. I realized I couldn’t do it in real life. But maybe I could figure it out in the screenplay world. After looking back through some of my favorite movies, I was able to identify a few things. These probably aren’t the only things that add soul to your script. But they’re the big ones. Naturally, most of them revolve around character.

RELATABLE CHARACTERS – Try to make your characters relatable in some way. There has to be something in them that’s identifiable so an audience can say, “Hey, that’s just like me,” Or “Hey, I have a friend going through the exact same thing!” This familiarity creates a connection between you and your audience that you can then use to extract emotion out of them. Because they now have a personal investment in your character, they’re more likely to care about what happens to them. It might be that your character loses someone close to them (Spider-Man), which is something a lot of people can relate to: loss. Or it might be that your character’s underestimated (Avatar), which is something a lot of us have felt in our lives. But make no mistake, if we don’t relate to the character in SOME WAY, chances are we won’t feel the power of your story.

CHARACTER HISTORY – Every day I believe more and more in character history (or character “biography”) and let me tell you why. The most boring characters I read are the most general ones. The characters I’m attracted to, the ones I want to know the most about, are unique in some way. And you can’t find the uniqueness in a person unless you know their history. Oh sure, you can give your character a quirky little habit to set them apart, like being a master harmonica player or something, but if you don’t know how or why he’s a harmonica master, it’ll just feel like a gimmick. The more work you do – the more you find out about who your character is – the more specific you can make them. If you know your character’s sister died in a car accident, for example, you can make them a cautious driver. If you know your character used to be fat, you can give him low self-esteem. If you know your character used to be a football star, he’ll probably always be bragging about the glory days. The more you know about your character, the more specific you can be. So take the time to write out those big character biographies and GET TO KNOW YOUR CHARACTERS.

CHARACTER FLAW – Creating a character flaw is a key part of giving your screenplay soul because it represents the thing about your character that most needs to change. We all have that, that monkey on our backs that won’t go away, that won’t allow us to reach our full potential. For some of us it’s that we’re not aggressive enough. For others it’s that we let ourselves be taken advantage of. For others still it’s that we don’t allow people to get close to us. By giving your character something to struggle with, you invite the audience to participate in whether they’ll overcome that struggle or not. And since we all have flaws ourselves, it’s something we want to see rectified. We believe that if our hero changes, WE CAN CHANGE TOO! It inspires us. It gives us hope. And for that reason, we *feel* something.

RELATIONSHIPS – In addition to addressing your characters individually, you want to address who they are with others. Remember that our entire lives are dictated by our relationships. The people we connect with on a daily basis are our world. So you want to spend a big chunk of your screenplay exploring those relationships. Start by finding relatable issues your characters are going through. Maybe a marriage is in trouble because the husband is a workaholic. Maybe two soul mates meet but it turns out one of them is engaged. You then want to explore the conflict and the issues in those relationships in a way that’s unique to your story. And really *think* about what your characters are going through. Treat them like real people with real problems. Lester Burnham in American Beauty had to come to terms with his wife no longer loving him. It resulted in a very real exploration of a dissolving relationship. Even the most famous action movie of all time, Die Hard, has a strong core relationship at its center – John and his wife. If you’re not exploring relationships as deeply and as obsessively as you can, you’re probably not writing very good screenplays.

THEME – The way I see it – Anybody can write a film with “stuff happening.” Those films can even do well at the box office if they’re targeted to the right demo. We’ve all seen (and quickly forgotten) Transformers. But the screenplays that are trying to say something, that are trying to leave you with something to think about, those are the screenplays readers put down and say, “Man, I have to tell somebody about this.” One of the most effective ways of doing this is to establish a theme in your movie, a “message.” Take a step back and look at your script as a whole. What is it about? What are the things that come up over and over again? Once you figure that out, you can subtly integrate that theme into the rest of your script. The Graduate, for example, is about feeling lost and directionless when you take your first steps into the world. Saving Mr. Banks is about learning how to let go. Screenplays without a theme, without a deeper message, will likely be forgotten hours after they’re finished.

IN SUMMARY

I don’t care if you’re writing a character piece, an action-thriller, a horror film or a coming-of-age movie, your script has to have soul. And it ain’t going to have it with a bunch of set-pieces and snappy dialogue. Those things help, but they mean nothing unless we’re attached to the characters, care about what happens in their relationships, and feel like there’s something deeper being said here. Plot is great. A great plot can take a script a long way. But if you want your script to hit the reader on an emotional level, if you want them to remember your script past tomorrow, you’ll need to inject soul. Hopefully these tips help you do it. Good luck!

Oh man, I’m Twit-Pitched out. Last night it all hit me and I just crashed, leaving a ton of work on the table, which I get to make up for today. Yahoo! Luckily, I have my trusted readers to pick me up when I’m down. Today’s review comes courtesy of longtime Scriptshadow reader and former reviewer Christian Savage, who takes on one of Scriptshadow’s favorite writers, Dan Fogelman. It’s another day at the office for Dan, selling ONCE AGAIN, a 2 million dollar spec. God do I want to be this guy.

Genre: Comedy

Premise: Two brothers raised to believe their father died find out their mom was lying to them and doesn’t know who their father is (due to a healthy sexual appetite in the 70s). So the two set out to find him.

About: Bastards sold earlier this year to Paramount just 24 hours after being put on the market. This is Justin Malen’s second sale, the first being a script titled “Prick.” He is also working on a project titled “Trophy Husbands” for Mike Judge to direct.

Writer: Justin Malen

Details: 112 pages (This is an early draft of the script. The situations, characters, and plot may change significantly by the time the film is released. This is not a definitive statement about the project, but rather an analysis of this unique draft as it pertains to the craft of screenwriting).

Should I give up with comedies? Is every modern comedy script just an idea with comedic potential for Vince Vaughn to improvise in? Is there such thing as a comedy spec that’s just…I don’t know…GOOD?? It seems like even when a good spec is purchased, the studio finds a way to screw it up. Going The Distance was a hilarious comedy spec. Its biggest strength was its edgy dialogue. So what’s the first thing they did once they bought it? They REWROTE ALL THE DIALOGUE! I guess when a “soft” director and huggable cast is added, the studio has no choice but to make changes but man, there’s something wrong with that process that needs to be fixed.

Anybody still with me? Have I whined you away yet? I hope not. Because guess what? Today’s comedy is actually pretty good!

Peter and Kyle are twins but couldn’t be more different. Kyle’s a cross between Keanu Reeves and Brad Pitt, while Peter’s a cross between a can of peas and a cherry pit.

Kyle doesn’t have a single identifiable skill. But an aspiring barbeque sauce maker spots him on the beach and asks him if he could use his silhouette for his sauce label. The sauce blows up, and Kyle becomes a millionaire off the royalties.

Peter, on the other hand, is a proctologist. He sticks his hand in assholes all day. But there’s actually a reason for that. You see, Peter and Kyle’s mother told them that their father died of colon cancer before they were born. Peter, then, is on a lifetime crusade to help others with the disease.

Well that’s about to change. In a twist only Meryl Streep with a bag of popcorn watching Mama Mia could’ve predicted, it turns out that their mother’s been lying to them this entire time! Dad didn’t die. She doesn’t even know who dad is! That’s because she was the world’s biggest slut back in the 70s. Their father could be one of a dozen men for all she knows.

The cool news, though, is that their mother was a REALLY GOOD SLUT. Like if they were ranking sluts, she would be at the top of the slut chain. She had sex with some really famous people, and right away the evidence points to their father being Hall of Fame quarterback Jack Tibbs! Kyle is besides himself. This is the coolest news ever! But Peter’s still thrown by the whole thing. He can’t get over the fact that his whole life has been a lie.

So they go and visit Jack, and even though they hit it off, Jack mentions just how much sex their mom had (a LOT!), and evidence points to there being more likely candidates than himself. So Kyle and Peter jetset all over the U.S., meeting their potential fathers, but can’t seem to locate “the one.” During that time, Peter finally unleashes the longstanding resentment he has for his brother, who’s lived this charmed life while he’s never had ANYTHING good happen to him. Looks like these two won’t just have to find a father. They’ll have to find each other (awwwwwww).

Let’s address the most important thing first. Bastards has a goal (find the dad) that a character DESPERATELY WANTS TO ACHIEVE (Peter wants nothing more than to find out who his father is and have a relationship with him). Since we sympathize with Peter’s earnestness and his frustration for always being second fiddle in his family, we root for him, and therefore want him to achieve his goal. All of this is set up in the first 25 pages. And when you do that well, your story writes itself. It has direction. It has purpose. The reader is never lost because he/she understands what the protagonist is trying to do. This is how to set up your story.

Bastards also nails the second act because remember what the second act is mainly about. It’s about exploring unresolved relationships between characters. And here we have a big one. Peter hates his brother’s perfect life. So that’s the relationship that needs to be fixed. But what I found unique, and really liked about Bastards, was Kyle’s role in all this. He was completely oblivious to Peter’s resentment. He loved his brother more than anything and would do anything for him. He was just clueless and naïve. So you didn’t have that cliché “both characters hate each other” thing that you see in a lot roadtrip movies. The dynamic was more subtle, and therefore unique.

Malen has also put story before comedy. I’ll be honest. I didn’t laugh a whole lot in Bastards. But I wanted to see if Peter was going to hash out his problems with Kyle and find his father. I can’t emphasize enough how important this is. It’s probably THE BIGGEST MISTAKE amateur writers make when writing comedies. They don’t care about the characters or the relationships those characters have. They rationalize to themselves, “Well it’s just a fun comedy! I don’t have to create deep characters.” And then they’re surprised when nobody’s into their screenplay. Readers say, “I didn’t really connect with the characters.” And the writer screams back, “But it’s just a light comedy! It’s not supposed to be about the characters. It’s supposed to make you laugh!” We don’t laugh unless we care. And caring typically comes from giving us characters we identify with and care about. I believe this is why a lot of people had a hard time with Mrs. Satan. It wasn’t that it didn’t have funny moments. We just never cared for or identified with the main character.

Comedy-wise, Kyle is the big star here. He’s pretty funny as the clueless guy with the perfect life. He not only has a Hawaiian model wife and three perfect children. But his wife is of the belief that men have strong sexual appetites that need to be satiated and if she’s not around, he should satisfy those urges. Because that will make him happy. And if he’s happy, his wife argues, then their marriage will be better. So the whole time Kyle is feeling bad because he doesn’t want to have sex with other women but has to, which just infuriates Peter to no end.

I don’t know why but I kept imaging Keanu Reeves for the role of Kyle. He needs a good comedy role and since I’m a Keanu apologist, I’m secretly hoping that that’s the way they’ll go. Anything so this isn’t another Vince Vaughn comedy. All in all, this is one of those perfectly executed comedy specs. Malen really showed his command of the craft here. It wasn’t funny enough to get an impressive, but everything else was so sound that I’m strongly recommending it.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[xx] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: A few weeks back I wrote an article about how to juice up your scenes. One of those tips was to add a THIRD PERSON to the scene. Bastards showed how to use this tool effectively. In these types of movies, you’re always going to have the scene where the characters finally blow up at each other. It’s the “You Wanna Know What Your Problem Is!” scene where each character tells the other what there big “fatal flaw” is. Because we’ve seen this scene so many times, it’s become cliché. But what Malen does here is he adds a third character – a hitchhiker they picked up – and it adds a different flavor to the fight that actually makes it funnier and a bit unique. The hitchhiker is the one that senses the tension between the brothers, instigates the fight, and then referees it. It’s a small thing but this is what screenwriting is about. Finding those little things that make scenes feel different!