Genre: Adventure/Fantasy

Premise: When a construction worker goes missing during the restoration of an old pier, a group of kids go searching for him, only to find out that the pier is haunted by evil mermaids.

About: “The Pier” finished in the runner-up spot on last year’s “Brit List,” the list of the best unproduced scripts written by British writers. While the Brit List hasn’t exactly lit the world on fire in recent years, Hollywood definitely took notice this time. Writer Jay Basu was courted to adapt one of the biggest video games of all time, Metal Gear Solid, and was also brought in by Universal Pictures to join its “Monsters Universe” team, the studio’s attempt to create a universe out of its famous monster franchises (the Mummy, the Wolfman, etc.). Finally, Basu was able to get credit on the sequel to now mega-director’s, Gareth Edwards, breakout indie film, “Monsters,” which is titled “Monsters: Dark Continent.” That film can now be found on Netflix.

Writers: Jay Basu (current revisions by David Bowers)

Details: 105 pages (June 2013 draft)

For every Jurassic World, there is a Pixels, a movie Sony was betting big on this summer but was barely able to scrape 24 million out of this weekend. This marks Sony’s ONLY big release this season, so the fact that it bombed worse than Jr. Pac-Man is devastating for a studio that has clearly lost touch with the public. I guess they have new people running the show now but if they’re not careful, they’re going to end up like United Artists.

Speaking of summer blockbusters, may I remind you of the man who invented the summer blockbuster? A certain bearded gentleman named Steven Spielberg? I don’t think today’s generation realizes just how much Spielberg changed the game. Before him, everyone wanted to make dark moody three hour thought-bombs. Spielberg wanted to make candy-bombs. And it completely changed the way we went to the movies.

Jay Basu is clearly channeling his inner-Spielberg with “The Pier.” This script has the big idea, the sense of wonder, the childlike curiosity – all the things that make a Spielberg movie a Spielberg movie. But is it any good? That’s the real question. A question that can only be answered with a Scriptshadow review!

We’re in a small seaside town known as Wharton Bay. At one point, this town was THE destination for the vacationing summer family. It had one of those super-piers, with restaurants and roller coasters – it even had a ballroom!

But an accident crippled the pier, leaving it unsafe, and ever since, it’s grown old and dusty. That is until Jake and Annie Campbell moved into town. Jake has raised just enough money to revive the pier with the plan of bringing it back to its former glory.

Unfortunately, just as major progress is being made, one of the workers disappears. This leads to an investigation that threatens to close down the entire operation. Which is where our hero, 12 year-old Ash, comes in. Partially deaf, Ash is Jake and Annie’s son. He realizes that if he doesn’t figure out what happened to this man, his family will have to go back to the big city, where everyone made fun of him.

So Ash teams up with his weirdo friend, Bones, his brand-new crush, Emma, and his older brother Liam and Liam’s girlfriend Natalie. The five head to the Pier, only to realize that the damn thing is haunted. As they sneak in and out of the various abandoned buildings, they realize the place is being watched over by… yup… evil mermaids who want to eat your soul!

The five must fight for their lives as they figure out a way back to shore. But the longer they stave off these deep sea demons, the more they realize that there’s something else going on here. Maybe these mermaids aren’t trying to kill them after all. Maybe this is just a big wet cry for help.

This was a perplexing one. If The Pier was up for a slot on Amateur Offerings, I’m pretty sure it wouldn’t win the weekend. I’m struggling to figure out why this got so much attention and I’m stuck between the fact that the Brit List isn’t very competitive, and I’m not as appreciative of family fare as maybe the industry is.

Either way, let’s start with the positives. This is a “mass-entertainment” concept. It’s the kind of idea that studios like because it appeals to that young demo that’s the least discerning and it snags that PG rating, which allows the most amount of people to see your movie.

Second, it takes a familiar premise and approaches it in a new setting. Obviously, The Pier is aiming to be The Goonies and it substitutes a pier for caves.

Third, we have a new type of monster. Basu flips the script here and takes what is traditionally thought of as a “good” creature, and turns him/her bad. That was kind of inventive and contributes to the coveted “same but different” sweet-spot Hollywood’s always aiming for.

I think I sometimes glaze over these things because they seem like the easiest part of writing to me. But then I remember how many bad and boring concepts I come across. The majority of writers out there don’t know or don’t care what the masses want to see.

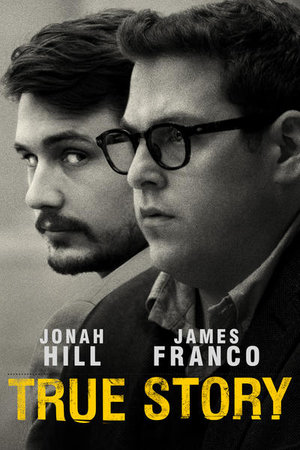

If there’s one thing you have to give “The Pier,” it’s that it FEELS LIKE A MOVIE. By that I mean, you can put it on a poster, you can create a great trailer. There’s action, adventure, excitement, scares. These are all MOVIE-LIKE things. Contrast that with, say, Jonah Hill and James Franco’s, “True Story.”

These are two of the bigger movie stars in the world. But look at this poster. Do you know what this movie is about? Do you see this poster and want to watch this movie? Does this even look like a movie to you?? That’s what I mean with “The Pier” when I say it FEELS like a movie.

But when you go into the actual execution of “The Pier,” it’s kind of baffling that this script garnered any attention. Every aspect of the script is extremely basic. You always know what’s coming 20 pages before it’s written because the writers aren’t interested in pushing the story in any unique or unexpected directions.

So you know we’re going into some dark room and we’re going to see a scary mermaid in the corner. You know in the next sequence we’re going to go into a carnival room of mirrors and we’re going to see a scary mermaid in a mirror. That’s the whole movie really. We just go from location to location on the pier and see scary mermaids.

And I suppose you can argue: “Well that’s every monster movie, Carson.” Isn’t that every episode of The Walking Dead? I guess, yes. But here’s the difference. Scripts can survive ONE element of basic or subpar execution. They can’t survive MULTIPLE subpar elements.

And that’s the thing. With, “The Pier,” the characters were very basic (less inventive versions of the Goonies characters). The plotting was very basic. The humor was very basic. The dialogue was very basic.

For example, here’s a line from Liam, the cool older brother, when he’s told they’re going to check out the man’s disappearance: “Like C.S.I. Wharton Bay? But instead of actual police it’s three dopey kids?”

What cool 16 year-old boy uses the word “dopey?” “Dopey” is a word a 45 year-old man uses.

Or here’s a representation of the humor in the script. Towards the end, when time’s running out, Ash says: “And if we don’t do something now, our story will always be about how five kids went missing out on Mermaid pier.” Liam quickly responds: “Three kids, two young adults.”

I’m not saying that’s a terrible joke. But it’s just so… plain. And that was my issue here. Everything was too plain. I’d imagine, if they were going to make this, that they’d bring in a big time writer to really elevate all of these choices, from the characters to the scares to the plotting to the dialogue. It’s way too reserved and safe, even more so than a script like Pixels, which only was allowed to slip through development because Sandler gets final say on the script and the man doesn’t give a single shit about quality.

And I think that’s the real issue here. When I read a script and I don’t feel like the writer TRIED HIS HARDEST – that’s something that I can’t get past. I KNOW there’s a better joke out there than, “3 kids, 2 young adults.” You can’t not know that. And if you’re not striving for the best you have to offer, why are you in the game?

Basu and Bowers should definitely be congratulated for coming up with an idea that captured Hollywood’s attention. It’s harder to do than you think. But I’m really surprised this script made as much of an impression as it did with its way-too-standard execution.

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Do a “Joke Pass” on every script you write. That means go through every single one of the jokes in your script and try to come up with a better joke. Even for the jokes you think are your best. I guarantee you’ll elevate half of the jokes in your script.

What I learned 2: Actually, you should be doing passes for every major element of your screenplay. You should do a character pass, a dialogue pass, a theme pass. By doing a pass where you focus on one specific thing (and not try to fix everything), you have a much better chance of keying in on what’s wrong/missing with that thing and fixing it.

Get Your Script Reviewed On Scriptshadow!: To submit your script for an Amateur Review, send in a PDF of your script, along with the title, genre, logline, and finally, something interesting about yourself and/or your script that you’d like us to post along with the script if reviewed. Use my submission address please: Carsonreeves3@gmail.com. Remember that your script will be posted. If you’re nervous about the effects of a bad review, feel free to use an alias name and/or title. It’s a good idea to resubmit every couple of weeks so your submission stays near the top.

Genre: Biopic

Premise (from writer): A Southern black folk singer walks the line between a violent criminal life and becoming a great American musician.

Why You Should Read (from writer): Inspired by the likes of “Raging Bull” and “Thirty Two Short Films About Glenn Gould”, “Sessions of Lead Belly” is stylistic bordering on surreal and strives for quality even at expense of authenticity. — The nonlinear structure throughout different periods in Lead Belly’s life of the early 1900’s is patterned to best draw interest and convey information, exploring who Lead Belly is and why, as well as the futility of triumph and meagerness of survival against all odds. — Every sequence is nearly standalone, playing out as ambitious mini-stories and innovative short films, each with a calculated build and unique style.

Writer: Cody Kerr

Details: 124 pages (this is a slightly different draft, I’m told, from the one that appeared on Amateur Offerings – Cody has reworked a few things based on your suggestions. That’s the draft I’m including in this review)

As we head into a strangely mediocre movie weekend that includes films like Pixels (quite possibly the most vanilla execution of an idea I’ve ever seen), Paper Towns (a John Greene novel that, based on the trailer, appears to change plots 17 different times) and Southpaw (Can we just be honest here and admit that the only reason these boxing movies get made is because an actor wants to show how good of shape he can get in for the role?), my question to you is, “What do you wanna see?”

No, not between these three movies. I know you don’t want to see any of those. I mean, are there movies out there you wish were being made but aren’t? What are the ideas? What are the genres? Are you like me? You know you want something different, you just won’t know what it is until you see it. I suppose that’s part of being different. Is you just don’t know what it is until it’s placed in front of you.

Well, one thing that audiences have definitely been more into lately is biopics. David O. Russell’s “Joy” trailer just debuted and while I’m pretty sure whoever cut that trailer did 11 lines of coke right beforehand (it’s a movie about a woman who makes the miracle mop that doesn’t include one mention of the actual mop), I’m sure subsequent trailers will get everyone revved up to see it, because the script was damn good.

Which brings us to today’s screenplay. Cody Kerr is hoping to capitalize on the biopic craze by introducing us to a controversial singer from the first half of the 20th century. Is “Sessions of Lead Belly” going to garner a David O. Russell like visionary to attach himself and make it the next big biohit? Let’s find out!

At various points between the 1910s and 1940s, we follow a man named Lead Belly, a black musician who likes to sing about a variety of things like slavery, shipwrecks, and Hitler. In the 1920s, Lead Belly suspects his wife’s cousin is sleeping with her, so he shoots and kills him.

Once in prison, Lead Belly becomes extremely popular as he loves to perform for the other prisoners and the prison staff. This ends up getting him out of prison after only 7 years of a 35 year sentence. Once out, Lead Belly struggles with a drinking problem, and strives to shed his “murderer” image in an attempt to be taken seriously.

But problems seem to follow the man wherever he goes and, I believe (to be completely honest, it was hard to understand what was going on a lot of the time here), he killed a second man and had to serve a sentence at another prison. But Lead Belly kept fighting, getting out of prison again, and ended up making some of the best music ever recorded by man.

Something we don’t talk about a whole lot here on the site is CRAFT. Craft is the ability to put a clear story together within the unique constraints of the screenplay format. While reading Lead Belly, I could see how much love and emotion was infused into the story. But what I didn’t see was craft – the ability to take that emotion and make sense of it. There’s too much going on here. There’s too much jumping to different years for no reason. There are basic clarity mistakes being made in almost every scene.

I felt like a detective wading through this script. I had to piece together clues just to keep up with basic story points. For example, there’s this guy named “Huddie” in the script. Then there’s this guy named “Lead Belly” in the script. Well, low and behold, at around the mid-point, I found out they were the same people!!

That’s really basic clarity stuff that you don’t want to mess up on. Just use one name the whole time. And if you absolutely have to change the name in the script (which sometimes happens), fucking throw a fireworks party worth of attention at it. “JOE IS NOW FRANK!!!” (that’s a slight exaggeration – don’t use exclamation points – but do make it damn clear).

And to get into this a little deeper, consider how this issue plays out on the reader’s end. Sessions of Lead Belly jumps all over the place in time. It’s 1942, 1917, 1930, 1938, 1918. We’re already struggling to keep up with all this jumping around. Then on top of that you change the main character’s name on us? So in some sections he’s one name and in others he’s another? I almost want to ask: Are you purposefully trying to confuse us??

Actually, this kind of thing happens a lot with new writers. They want to be different. They want to be edgy. They want to fix the very issue I brought up at the beginning of this review. They want to make something different that people haven’t seen before.

But they don’t understand the craft yet so they don’t know how to pull of this edgy approach. When you’re jumping through time a lot, one of your jobs is to become something I call: a grandmaster hand-holder. You need to do a lot more hand-holding with the reader than normal, because we’re being thrown around into too many time periods and if you aren’t EXTREMELY CLEAR about where we are, we’re going to get confused and eventually check out.

And I’ll be completely honest – by page 70 I started skimming. And I rarely do that when I review a script but, damn, I was so confused and frustrated about where we were and what was going on half the time, I just didn’t have the mental capacity to keep trying to figure things out. I felt like the writer had made things way more confusing than they needed to be.

And for what purpose? What was gained by these time jumps? They seemed to be there to be there. To give the script an “artsier” feel. If I felt some purpose behind them, I might’ve been more receptive. Like the opening scene shows someone stab Lead Belly. If the rest of the movie would’ve been a lead up to that moment, I would’ve understood the purpose behind starting with that flash-forward. But we don’t get that. We’re just randomly thrown into various years and expected to keep up.

And also – and maybe this had something to do with me expending so much energy on figuring out where we were in the story – I never felt like I understood Lead Belly’s problem. What was the main thing he was dealing with in his life that he needed to fix?

Cause when you write a biopic, “what he needs to fix” is the heart of your story. Unlike regular movies which have goals for the characters to achieve, biopics are all about the main subject figuring themselves out – or at least coming to peace with who they are. It’s been forever since I saw the Johnny Cash movie with Joaquin Phoenix, but I remember in that movie, Cash couldn’t get past the fact that his father didn’t love him, didn’t approve of him. That’s what the movie kept coming back to.

I couldn’t figure out what was “wrong” with Lead Belly. And, actually, because the script was laid out in such a confusing way, I had to go to Lead Belly’s Wikipedia page to fill in the gaps. And what I learned was that he had a really bad temper. That seems like something that could’ve been explored. Especially if that’s the reason he murdered two people. A man learning to control his inner rage and trying to become a better person – I definitely could’ve gotten on board with that.

But, again, I think Cody just needs to write a few more screenplays and get a better feel for how this craft works because, unfortunately, just feeling emotions about your character and jumping around to moments in their life – that isn’t enough. There has to be a plan and a theme (that thing your character is trying to overcome) clearly established. The destination has to be better laid out (where are we going??). And simple things shouldn’t be needlessly complicated.

And I’m going to end this review by saying this – because it continues to be the number 1 reason that amateur writers screw up their screenplays: Stop trying to be so complex. Just tell a simple story. If it’s a good story, we’ll enjoy it. I promise.

Screenplay link: Sessions of Lead Belly

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Grand Master Hand-holding. The more complex your story is (the more time jumping, the more characters, the more subplots, the more plot points, the more plot twists), the more you’re going to need to hold the reader’s hand during the story. Never be afraid to be clear. I know some writers are scared of being too “on the nose,” but I’d much rather be sure of something important (like that a character from the 1920s with one name and a character from the 1930s with another name are actually the same person) than be left guessing.

How to avoid the “aimless riffing” issue that plagues Apatow’s newest film.

So I went to see Trainwreck last night and, holy shit was it boring! The trailer makes the movie look really good but that’s because the trailer does the one thing the film doesn’t do, which is to FOCUS THE DAMN STORY.

Judd’s biggest issue is his propensity to let scenes drag on for too long. If you saw Trainwreck, chances are, you felt the way I did – which is that the scenes never ended. While a script can survive one or two drawn-out scenes. It can’t survive a bunch of them. And it definitely can’t survive ALL the scenes being that way.

And I understand why Apatow does this. He’s very much a “workshop the scene” kind of guy. He’ll start with the scene as written, then play with it on set, allowing the actors to riff and try a bunch of jokes, the objective being to stuff as much comedy into each scene as possible.

Unfortunately, movies don’t do well with that plan. They like when everything is tight, focused, and to the point. They like when scenes feel like they have a purpose. So in honor of this terrible movie, and Apatow’s lazy approach to scene-writing, it’s time to remind ourselves what the principles of good scene-writing are.

1) Give your featured character an objective in the scene – The key character should have an objective in each scene. This is their “goal.” Play the scene out until the character either achieves or fails at this goal. As soon as one of those two things happens, the scene is over. Notice I said “key” character and not “main” character. That’s because sometimes, someone other than your main character will have the objective in the scene. For example, if your main character gets called into their boss’s office to get fired, it’s the boss’s objective that’s driving the scene (to fire your main character).

2) Get in late, get out early – Good God could Apatow have benefited from this Screenwriting 101 advice. The main reason scenes drag is that you either came into the scene too early or stayed with the scene way too late. Once you know what your key character’s objective in the scene is, try to start the scene as close to that objective as possible (unless you’re trying a specialized dramatic technique – more on that in a sec). So to use our “firing” scene again, get us in that scene right when the boss is about to fire her! Then, once that’s done, cut to the next scene! In Trainwreck, after the boss had fired Amy, we actually STUCK AROUND as two co-workers entered the scene and asked if Amy had been fired yet. It was an attempt to be funny but no one laughed because the objective had already been reached. Whether Apatow knew it or not, he had signified to the viewer that the scene was done. Now had those co-workers walked in and asked this question BEFORE the firing had happened, it might’ve worked (and that actually sounds like it would’ve been funnier). But you can’t do that after all the air has already left the balloon.

a. (Specialized Technique) – Yes, you typically want to come into a scene as late as possible. But there are some instances where a drawn-out scene opening can work. For example, if you utilized some dramatic irony and informed the audience ahead of time that Amy was getting fired (something Amy doesn’t know), now when Amy walks into her boss’s office, you can introduce a few pages of conversation before the firing happens. Why? Because you’ve added the element of anticipation. We know the bomb is going to go off, so there’s an added element of tension to the interaction. So yes, you can ignore the “get in late, leave early” rule (just like you can ignore any rule). But you should have a good reason for doing so.

3) Conflict – This, Apatow knows how to do. He knows that in every scene, there needs to be some sort of conflict driving the scene. Without conflict your characters aren’t trying to work through anything – aren’t trying to come to a conclusion on anything – which leaves the audience wondering why the scene is being included. You could feel conflict in Amy’s scenes with her first boyfriend (John Cena), who liked her more than she liked him, in the scenes with her father, who was always butting heads with Amy about her life, with her sister, who she didn’t see eye-to-eye with on anything, and with the main love interest, who she was afraid to fall for, leading to her sabotaging their interactions. Conflict is good, folks. Use it!

4) Stakes – The higher the stakes are in a scene, the better. If nothing’s on the line, the scene will feel pointless and boring. Obviously, not every scene can be of Level 100 importance. Your main characters can’t be about to break up every single time we’re with them. So you have to stagger the intensity level of the stakes. But there should always be SOMETHING on the line. I recently read an amateur script where two co-workers were kind of hungry so they went to get some pizza. On the way there, the subway train broke down, and we stayed with them for the next four pages as they tried to figure out how they were going to get their pizza. So our two characters weren’t even that hungry. They didn’t have anywhere important to be. They decided to get pizza on a whim. The train broke down, preventing them from getting their food…. Why is this scene supposed to interest us? It doesn’t. Because there’s nothing on the line. You gotta add those stakes, people.

5) Urgency – Urgency is probably the least important of all the scene tips I’m offering today, but don’t underestimate its power. If you put a timer on a scene, you can really add some life to it. Couple it with some high stakes and, baby, you’re cooking with gas. If, for example, in the aforementioned subway scene, we changed it so that our two workers were trying to make it across town for the biggest meeting of their life? If not making it to that meeting meant their company lost a 400 million dollar deal? And they only had 10 minutes left to get there? Now you have a scene that people are going to care about.

6) Necessity – Finally, make sure the scene you’re writing is necessary in the first place. The worst scene is the one that doesn’t need to be in your movie. To know which scenes you need, know what your main character wants in the movie. What’s his goal? In Die Hard, John McClane wants to save his wife from the terrorists. So if you include a scene where John McClane goes swimming in the building’s swimming pool, that scene’s probably not going to play well, is it? That’s because it doesn’t get Johnny closer to saving his wife. Where I see this mistake the most is when the writer doesn’t know what their movie is about in the first place. Since they don’t know what their hero’s after, they can’t plan which scenes are needed to get them there.

Feel free to offer your own scene secrets in the comments section. For example, sometimes you want to “turn” a scene so that it goes in a different direction than the audience thought it would. This is really important in comedy. I was watching Modern Family the other day and uptight married couple Phil and Claire get stuck on a double-date at a nice restaurant with their hillbilly neighbors. You think you know where this is going (the hillbillies are going to cause a scene, being loud and boisterous, embarrassing Phil and Claire), but instead, the hillbillies bust out a nice bottle of wine, have a stellar rapport with the wait staff, and begin bragging about their son being accepted to Julliard.

Don’t just help your fellow writers with these tips, help Judd Apatow. The guy definitely needs to improve his scene work.

Genre: Drama

Premise: After a plane crash, a man who lost his wife and daughter in the accident hunts down the flight controller responsible.

About: This is a really hot spec that went out recently from the writer of “Enemy.” Fox was so impressed by it, they hired the writer, Javier Gullon, to adapt a recent novel they purchased, The Dark Side. That book is set in the future where the moon is used as a penal colony, and a detective is called in to investigate the murderous rampage of a robot. “478” quickly got Arnold Scwarzeneggger attached and Darren Aronofsky to come on as producer. The Aronofsky attachment is interesting as you may remember Aronofsky briefly being attached to “Moonfall” last year, a Black List script which was famously pitched as “Fargo on the moon” (it wasn’t that at all, by the way). Aronofsky being attached to a project (478) so closely linked to another “murder on the moon” project (The Dark Side) makes you wonder if Aronofsky is getting moon movie fever. Might we see an Aronofsky moon murder film yet?

Writer: Javier Gullon

Details: 95 pages – Nov. 2014 draft

In case you haven’t noticed, one of the themes I’ve been pushing lately is TRUTH. I read so many screenplays – particularly from amateurs – where the writer isn’t being truthful with his choices.

Even if it’s clear that people would NEVER do this sort of thing in real life, the writer figures that if it works for their story, they’re going to include it.

The poster child for false choices is, of course, when the babysitter hears a noise upstairs and goes to check it out. Yeah, it’s better, entertainment-wise, if the babysitter goes and checks out the noise. But if we know that would never happen in real life, we call bullshit. Which is why you rarely see this happen anymore unless there’s a truthful reason behind it (if the baby is upstairs and therefore it’s paramount to make sure he’s safe).

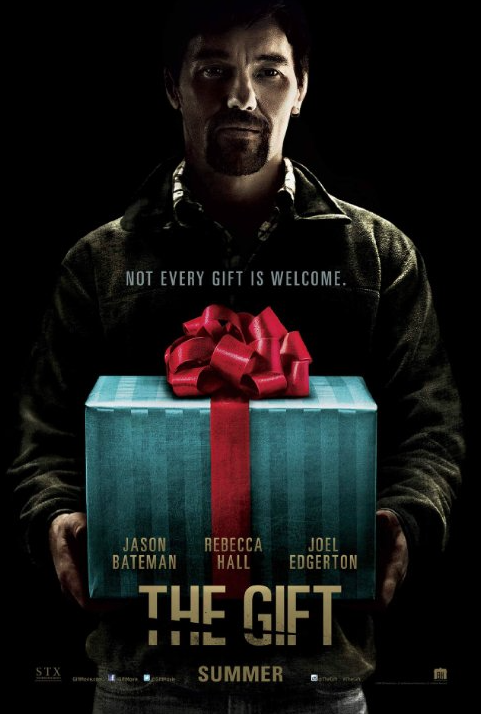

Even yesterday’s script, The Gift, violated this code. There’s no way Robyn, the wife, would’ve been so inviting to this creepy weirdo. It was clear that the man had a few screws loose and was potentially dangerous. Yet, because keeping him around was the more entertaining option, Edgerton opted to “cheat” the Robyn character and make her more accepting of Gordo than the real-life version of Robyn would have been.

However, today’s script taught me the flip side to the “truth” argument. What if you’re TOO truthful? What if you become so enslaved to the truth, you consistently pass over much more entertaining choices? That was my issue with 478. There’s no doubt the script portrays things the way they would REALLY happen. But that’s the problem. The way things really happen is often boring.

44 year-old Viktor is a construction contractor. After a particularly long day of work, he heads to the airport to pick up his wife and daughter, who are flying in from Russia to permanently live with him in America.

When he gets there, he’s ushered into a private room, where he’s told that two planes have collided, and that there are no survivors. And, oh yeah, one of those planes was carrying his wife and daughter.

The next few days are hell for Viktor, who ends up volunteering for clean-up at the crash site. Amazingly, he stumbles across his daughter’s pearl necklace, which becomes a media symbol for the tragic event.

After trying to get therapy and heal properly, Viktor can’t stop thinking about the man responsible for the crash, the traffic controller. So he goes on a road trip to find and kill him.

The second half of the script takes us back to the day of the crash, this time from the perspective of Paul, the flight controller. We observe a number of unavoidable mistakes in the room which would eventually cause the crash.

We then follow Paul back home, where his wife and son try to deal with the aftermath. They routinely wake up to people painting shit like “Murderer” on their front door.

Eventually, Paul’s wife thinks it best if her and their son move out. This sends Paul into a spiral where he changes his name and moves to another state to start over. But then, 478 days later, there’s a knock on his door. It’s Viktor. He wants to settle the score. And he’s not leaving until he does.

So the “truth” I was referring to earlier refers to the fact that this script is played as straight as it gets. There are no shocking twists (someone sabotaged Paul’s computer right before the crash!). It’s: Dude sort of fucked up. People died. No one’s happy about it.

I mean we know where this is all going by page 20. Viktor’s going to kill Paul. And I suppose there’s an element of suspense to that – we’re eager to see how that goes down. But not really, since we already know how it’ll end. You can tell this isn’t the kind of script where Viktor overcomes some flaw and realizes that killing Paul won’t fill the void in his heart. No. Viktor is miserable. He will be miserable for the rest of his life. And killing Paul will make that misery a teensy bit easier to manage.

While I’m not saying this needed some fancy twist, it definitely needed… something. Some sort of dramatic element to give some life to the story. It was so freaking straight-forward. There isn’t even a lesson to learn here. It’s not like Paul was drinking on the job that day (like the Denzel Washington film, “Flight”). Or was being negligent. He was just a little distracted due to his partner leaving the room. There’s nothing he could’ve done differently. And therefore, there’s nothing for him to come to terms with, to “learn” about himself.

Yesterday I remarked how The Gift used the plot point of the husband becoming a villain to fuel the second half of the screenplay. We didn’t get anything like that there. The people who are miserable on page 20 are the same people who are miserable on page 90. There’s nothing, like that film, that helps us see the story any differently.

We did switch perspectives to Paul, which was somewhat of a change. The problem was, Paul was no different than Viktor. They were both miserable guys whose lives were spiraling out of control due to depression.

So if there’s a lesson to be learned from 478 – it’s that “truth” is important up to a certain point. You still need to add drama to your story. You still need to entertain. And if that means adding an exciting plot choice that probably wouldn’t happen in real life, well, you have to consider it. Because, in the end, nobody’s going to give a shit about your story unless they’re being entertained by it.

You still want to be as truthful as possible. But I realize I’d rather be entertained by a lie than bored by the truth.

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Real life is pretty boring. Therefore, if you try and follow it to the letter, your script’s probably going to be boring as well. Take some dramatic license, add a few fun plot points, and never forget to entertain us, even if you have to fudge reality a bit to do so.

Genre: Thriller

Premise: A newly married couple move back to the husband’s home town, where they run into his old high school classmate, a strange man who used to be known as “Weirdo.”

About: Australian actor Joel Edgerton clearly has bigger plans for his career than just preening for the camera. Edgerton wrote, directed, and starred in today’s script, which hits theaters in a couple of weeks. Because this is a contained low-budget thriller (and sort of horror), it is of course produced by Jason Blum. If you want to know how to get Blum to buy YOUR script, well, I can’t give you a definitive answer. But I can tell you why he responded to this script: “I was very compelled by this notion of, you slight someone in the past and you think they’ve forgotten—and they haven’t. And I really like the idea that the way that person may, or may not, be getting revenge is by giving you a series of gifts that start off nice and grow meaner and meaner and meaner. I thought those were very relatable things.” Notice how Blum’s responding to the “concept” nature of the pitch. The “gift” part. That’s how he realized he could market this. Which is why, not surprisingly, he had the title changed from “Weirdo” to “The Gift.”

Writer: Joel Edgerton

Details: 115 pages (May 2014 draft)

They just don’t make these films anymore, do they? It used to be that a good thriller would fetch an A-list star and ensure a 2000 screen release. But now, unless the idea is incredibly clever (Gone Girl) or somehow fetches a great director (Gone Girl), these films go straight to Digital. Like the 2014 film, The Guest. Solid movie. But went straight to Itunes.

And it’s too bad. Because I miss these films. They’re a nice vacation from Fancy Capes McGuillicuty and his band of merry freak friends releases (Avengers 1&2).

And I have a theory why they’re disappearing which I’ll share with you after the plot breakdown but the good news is, it looks like “The Gift” (“Weirdo”) is one of those rare thrillers that’s getting a wide release. Or, at least, I just saw a giant billboard promoting it, which would suggest it’s getting a wide release. So there must be something special going on here, right?

“Weirdo” begins when recently married couple Simon and Robyn move into a new home back in Simon’s old town. While the two are out furniture shopping, they bump into Gordo, an old classmate of Simon’s from high school.

Gordo seems excited to see Simon but something in Simon’s reserved reaction tells us there’s more to this story. In the following weeks, Gordo keeps finding reasons to stop by, and while Robyn finds it endearing, Simon is pissed. Especially when Gordo starts stopping by when he’s at work.

It isn’t long before Simon’s had enough, and tells Gordo that they don’t want him around anymore. But his absence only seems to create more stress. Robyn becomes convinced that, because they upset Gordo, he’s going to do something bad.

Eventually, Robyn learns that Simon’s not telling her everything about what happened back in high school. Apparently, Gordo was caught having sex in a car with an older man, and the fallout led to everyone making fun of him and him having to leave school.

At least, that’s the story told at first. The more Robyn looks into this, the more she realizes it may not be Gordo she should fear. It may be the man she shares her home with.

So here’s the conversation I’ve been having with a lot of writers lately – writers who are trying to figure out what to write about. Movies are becoming more and more about “moving” than they ever have before.

The barrier for entry on your average weekend film is getting larger and larger. Films need to look more impressive than ever before. They have to look bigger than they have in the past. They have to be flashier.

And the key ingredient to creating all of these things? – MOVEMENT.

We need to see a lot of movement on screen. Moving from location to location. Characters moving from one place to another. Moving in cars. Moving in action scenes. There has to be a sense of movement on the screen. And this is always how movies have looked best. But you used to be able to get by with more stillness in film. Nowadays, it’s tough.

If you have a trailer where shot after shot is people standing around, it looks like not a lot is happening. And many people equate that with boredom. Some trigger goes off in their head that says, “Movie I’d rent. But not go see in the theater.”

The lone exception to this seems to be the horror film. And the reason the horror film can survive in this environment is because the writer has the power of fear on his side. He can create fear – one of the most powerful emotions an audience can have – in the smallest and stillest of venues. And actually, it seems like the smaller the room, the scarier things get. In that way, the stillness, the limited locations, actually aid the movie.

But the contained (or low-budget) thriller isn’t exactly horror. It’s a form of horror, but it lacks those big scares that only a horror film can provide. And that’s why these films are getting marginalized. That’s why they’re getting sent straight to video. The Gift seems to be one of the few films who have maneuvered around this pitfall.

So how was it? Well, the danger when you’re writing a script like this is: Is there enough in the tank? Do you just have a scary guy coming around and being scary and that’s it? Because if that’s the case, we’re going to be bored by the midpoint.

You need to find an extra gear – one more big plot point – to get an idea like this to the finish line. And while Weirdo’s plot point isn’t a slam dunk, it’s good enough to finish the race.

What is that plot point? We need to get into spoilers to broach it so avert your eyes if you don’t want to know. The coup of this script is that Edgerton makes us start questioning who the real “weirdo” is.

About 3/5 of the way into the story, Robyn begins to realize that her husband isn’t telling her the whole story about what happened to Gordo. And this does two things from a storytelling standpoint. First, it creates a mystery we want the answer to. We want to know what happened to Gordo. And second, it makes us start questioning Simon. Is he the real danger here?

So it’s kind of cool because the first half of the script creates this “impending sense of doom” around the character of Gordo. And the second half creates an “impending sense of doom” around Simon. If they only would’ve stayed with the first of these characters, I don’t think the script could’ve lasted. Trying to ride one single fear through an entire movie is hard to do.

This is actually the problem The Guest had. Cause it was kind of the same situation. A guy moves in with this family who we feel is dangerous. And that’s really cool on page 15. But it gets kind of stale by page 85. He was just more crazy than he was earlier.

So while Weirdo wasn’t perfect, that story choice made it a movie. It’ll be interesting to see how the film does because it truly is a “still” type movie. And without that straight-horror tag, that’s going to be a hard sell. We’ll have to see.

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Always pay attention when an actor writes a role for him/herself. It gives you direct insight into what kinds of characters actors want to play. Which here is someone scary, unpredictable, and a little bit crazy – all things that allow an actor to display their acting chops.

What I learned 2: For British and Australian writers, there are no “queues” in the United States. Only lines! I bring this up only because I see it a lot. And I don’t mind it if the movie is set in Australia or Britain. But if you’re going to set it in the U.S., make sure it’s a line!