Genre: Fairy Tale/Family

Premise: When Prince Charming gets his ass kicked by a former girlfriend, the Kingdom must entrust itself to his doofus twin brother, a man who can barely tie his own shoes.

About: This script sold… well, yesterday. Doesn’t get much hotter off the press than that. Disney continues its desire to turn its stable of historic cartoons into live-action counterparts. We saw it with Malificent, Cinderella, Beauty and the Beast is in the works, and now Prince Charming. You may be asking, “Why?” Well, contrary to popular belief, there still isn’t a guaranteed formula for turning out profitable movies. So if a studio sees something that even remotely works, they hop on that trend until it stops working. The big difference with today’s script is that the writer wrote it on spec. Which means that the studio wasn’t involved. And this is good news for YOU GUYS as it demonstrates a writer identifying a studio need and filling it. That’s what all of you should be trying to do. Writer Matt Fogel was an assistant to Phil Lord and Chris Miller on their film, Cloudy With A Chance Of Meatballs. He also worked on the upcoming Tom Cruise project, Bob: The Musical, an earlier draft of which I reviewed last month.

Writer: Matt Fogel

Details: 100 pages

So yesterday I learned they’re doing a Han Solo origin story. Phil Lord and Chris Miller have finally been entrusted with a legitimate property and I couldn’t be happier for them.

But you know who I’m not happy for? Me.

The cool thing about Star Wars is that it’s this entire universe. It dates back thousands of years (where some of the video games take place). Disney bought this universe and their solution is to give us… a Han Solo origin tale? That seems so… risk-averse. Which I guess studios are. But I thought the whole point of these anthology movies was to take chances. Play it safe in 7, 8, and 9, but with these other films? Get a little wacky. Wear a dress for the night. Eat a box of brownie mix without baking it.

I suppose there’s too much money for them to take risks. But I’m telling you. There’s a reason your protagonist is typically the straight-man. It’s so he can anchor the movie. Once you try and make the “disruptor” character the lead, you end up having to neuter him to keep the movie grounded. I’m just not sure Han Solo or Boba Fett were ever meant to lead a film. I guess we’ll see, though.

So Prince Charming really isn’t about Prince Charming at all. It’s about Prince TREMBLING, Prince Charming’s lesser-known twin brother. You see, Prince Charming’s problem is he’s a little… too charming. Or, to be less vague – the guy bangs a lot of chicks.

At a certain point, he’s alienated so many women that he gets attacked by one, sending him into a coma. This is not a good time for the Kingdom to have a prince in a coma. The King is dying and the princess has just been kidnapped by their rival, King Antagony.

The King’s cabinet feels that if they don’t rescue the princess, King Antagony will sense their weakness and take over their kingdom, Game-of-Thrones style. This leaves them with only one choice, to pass Prince Trembling off as Prince Charming.

This is not an easy task as Prince Trembling is a coward who stumbles through life like a 16th century drunk Michael Cera. So Prince Trembling is put through a crash course of charm school and fight school in order to appear as the real Prince Charming.

Because everyone here knows it’ll be impossible for Prince Trembling to actually rescue someone, he’s sent to recruit a crazy pirate named Peter Wild, a man the real Prince Charming is quite chummy with. Prince Wild will facilitate the rescuing, get the princess back home, where she’ll marry the real Prince Charming once he wakes up, and everyone will live happily ever after.

But a problem arises when Peter Wild isn’t Peter Wild at all, but Snow White in disguise! Because Snow White is Prince Charming’s ex, she has a hankering to kill him. But when she realizes he’s actually Charming’s twin brother, she starts to like him.

Will the two be able to rescue the princess and save the kingdom? I’m not a betting man but I’d probably bet every cent I own on yes. Especially since I’ve read the script and know how it ends.

I’m not sure there’s much to learn from this script, to be honest. I mean, we’ve got our GSU in place, which is ESSENTIAL in any mainstream studio film. Goal – save the princess. Stakes – if they don’t, King Antagony takes their kingdom. Urgency – they have a few days to pull the rescue off.

You also have a dramatic irony storyline in place, which works well in these kinds of movies. The audience knows that Prince Charming isn’t really Prince Charming. However, everyone else thinks he is. They didn’t do a very good job selling this unfortunately (I was never convinced that if he was caught, it would change anything), but it was there.

My biggest issue with the script was Prince Trembling. I guess I assumed that if they were going to use a twin storyline, they’d make Charming’s twin his polar opposite. He’d be off-putting, socially awkward, and a miserable guy. You know, the opposite of charming!

Instead he’s just scared and goofy. Which didn’t make a whole lotta sense. I suppose it allows him to slip and fall a lot but slipping and falling, while allowing the character to get some cheap laughs, doesn’t do much in the way of character development. And Disney movies are all about character development.

I guess we get to see him go from cowardly to brave but, again, what do fear and bravery have to do with Prince Charming? It feels like we’re exploring themes that are a million miles away from our title character. Let’s explore issues that revolve around charm or womanizing or how our society is obsessed with looks. These are the talking points Prince Charming brings to the table.

These aren’t things I’d be harping on if this were more of a general fairy tale. But this movie is titled “Prince Charming.” We should be breaking down what that name, what that persona, means.

You may also be asking, “How do you do anything different with these kinds of movies?” They’ve been done to death. And I was asking the same thing. Well, the way you evolve these fairy tales is to integrate progressive ideas, and issues we’re dealing with today that we weren’t dealing with the last time this movie (or this type of movie) came out.

The hot topic right now, of course, is feminism. So it turns out the pirate Peter Wild isn’t a male pirate at all, but Snow White in disguise (yes, I groaned as well). This allows Disney to make an ass-kicking female character who thinks saving princesses is lame, which in turn allows us to explore some territory we haven’t explored in fairy tales before.

But the big takeaway from this sale is clearly Fogel’s business-savvy. He not only knew that Disney was looking for live-action versions of their famous characters. He also recognized that Disney wouldn’t need spec scripts for its well-established film properties (Beauty and the Beast, The Lion King). They’d be developing those films in-house for sure. So he went for one of their peripheral characters, someone they likely hadn’t developed a script for. Smart!

While I would probably take my imaginary daughter to this movie, the character of Prince Trembling was a little too lame for me. And thusly, I can’t recommend it.

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: When you write movies in the fairy tale universe, don’t limit yourself to just characters and ideas that have been explored before. Look for lesser known characters, or even completely new made-up characters, to add to the mix. These additions are what’s going to help your script stand out from the competition. So, for example, Fogel introduced this character named “White Knight.” We’ve heard that name before, of course. We have vague ideas of what that it means. But Fogel built an entire storyline around White Knight whereby he was a suit of armor with nothing inside. He was an ideal as opposed to a real person. I’m not sure Fogel hit the character out of the park, but the effort to create that type of character in the first place is exactly what you want to do. If you’re only sticking to the basics (Prince Charming, Snow White, a princess who needs rescuing), your script is going to be really generic. Those new unique characters are what’s going to make your fairy tale yours.

Genre: Comedy

Premise: A married couple who never got the opportunity to go to college due to having their son at such a young age, find themselves experiencing it for the first time 18 years later, during their son’s first Parents Weekend.

About: Parents Weekend is a hot spec that was snatched up last month by Lotus Entertainment. Writer Peter Scott has written two books and seems to specialize in the humorous adventures of married couples (one of those books is titled “In My House: A Humorous Journey Through The First Years of Marriage”).

Writer: Peter Scott

Details: 111 pages

I liked this idea as soon as I heard it. And I haven’t read a good comedy in it seems like forever so reviewing it today, on the 61st annual Comedy Day, it felt right.

I don’t know why comedies are struggling so badly. They used to be the number 1 spec genre out there. People would pick up anything as long as it had a scene where seven consecutive gay jokes were made. I guess the fact that the box office has gone global and comedies “don’t travel” has hurt the genre.

But people will always want to laugh. And comedies are still cheap to make. So there might be a chicken-or-the-egg scenario going on here. Is the reason there are less comedy scripts because there’s less of a need for comedies? Or have comedy scripts gotten so bad that the studios stopped buying comedies, which resulted in less good comedies, therefore tricking the studios into believing that comedies weren’t worth the risk anymore? I’m not sure that that’s a chicken-or-the-egg scenario but I just like any opportunity to use the phrase “chicken-or-the-egg scenario.” It also reminds me of breakfast. And breakfast is my favorite meal.

Personally, I think comedy scripts have always skated by on this “only needs to be okay” law. And that lowered the bar so low, that when comedy actually needed to be good all of a sudden to compete with dinosaurs (cause dinosaurs travel – I mean, they don’t travel with like suitcases or anything. But they travel in the sense that everybody knows who dinosaurs are. Except for maybe Sweden. I don’t think there’s ever been a dinosaur in Sweden), comedy writers didn’t have the tools to compete.

It was like, “What? You mean my ‘main character who only speaks in the language of projectile vomit’ isn’t good enough??”

Anyway, so, Parents Weekend. Sean is your typical grungy college freshman. However, Sean puts a little more effort into studying than your average student due to the fact that it’s been made abundantly clear to him that he was a mistake.

So big of a mistake that his parents, who had him when they were 18, couldn’t go to college and get real jobs. Which is why Mommy Sean (Amanda) works as a traffic court reporter and Daddy Sean (Nick) works as an assistant pharmacist.

Amanda and Nick are having empty nest syndrome since Sean left a few months ago. But unlike normal empty nesters, who are like 80, they’re only 36! Which has them stuck in a play-doh like haze wondering how they’re supposed to act (are we young and hip? old and responsible?).

Naturally, then, when they show up at Indiana University to visit Sean, they decide to see what they missed. And that means heading straight to the nearest party, where Nick’s pharmacy score of something called “Cholestrolux” becomes a huge hit at the party, making Nick an impromptu college legend.

Nick’s legendary status gets back to Sean, who’s beyond embarrassed. But Nick only wants more. So the next night he goes to an ABC party (Anything But Clothes – where was this party when I was in college??), meets a girl who swears her vagina tastes like raspberries, before finally being arrested by the cops for becoming one of the biggest drug dealers on campus.

This in turn gets Sean kicked out of school, and Amanda furious with him. And then all three of them die in a horrible car accident. Just kidding. Sean gets back into school and Amanda and Nick live happily ever after.

So what’s the verdict?

Well, let me put it this way. There was only one cafeteria at my college, and the guy who owned that cafeteria was so cheap, he only bought food that had some sort of defect, but still passed the minimum health code laws. Like he’d buy potatoes that had started to rot on one side, and then just cut off the rotting half and serve us the “good” side. Or he’d buy milk that was blue. Outside of the color, the milk was totally fine (or so we were told).

I’m not sure what this has to do with Parents Weekend….. Oh yeah! I never liked eating at that cafeteria. But after going 2-3 days without food, I had no choice. Especially after the local McDonald’s caught on to my Cambodian Fry Scam. I would go to that cafeteria and find just the right combination of retarded foods to satiate myself.

And that’s a little like Parents Weekend. This is not The Hangover or Ted. It doesn’t have any big huge laughs. It’s more like a steady diet of smiles and chuckles that satiate you and you go with it because you’re starving for funniness.

I do want to take this opportunity to discuss an issue I run into with comedy screenplays all the time though and that’s the “false conflict” plotline. Conflict is really important in comedy. Whether it be straight up butting heads (Rush Hour), sexual conflict (When Harry Met Sally) or something more nuanced (the weird conflict between Alan and Stu in The Hangover).

But for it to work, it has to be honest. If you try to force conflict that isn’t there, the comedy never plays well. So here, we have this whole plotline where Amanda and Nick “break up” in the middle of the script due to a fight (which was a false plot point – but that’s a lesson for another day).

From there, Amanda runs into a handsome professor, and the two start a flirtationship. The conflict is supposed to come from the possibility that Amanda will hook up with the professor. But we don’t believe she will for a second. We’ve clearly established how much she loves her husband and the script never established that it would do anything risky, so we knew it wasn’t going to start with these two.

If you’re going to add conflict to your comedy (and you should – lots of it – just like you should do lots of drugs in college), you want that conflict to feel honest. Because if we really believe that Amanda could be with this guy, the story gets more interesting and the jokes play better, because real life (as opposed to safe-movie-life) is always funnier.

None of this is to say that Parents Weekend is a bust. To go back to my college analogy, it’s sort of like when the weird guy who lives down the hall from you who you don’t know that well invites you to his room during Easter Break weekend because everyone else went home and he makes you drink a case of 40s with him while he tells you that he wouldn’t be surprised if his girlfriend committed suicide earlier in the night. You’re so drunk that you’re kind of having a good time. But something in the back of your head is telling you that this isn’t right.

Parents Weekend was comforting like that. And, truth be told, it’s a clever way into a sub-genre that hasn’t had the most success (college comedies). I mean how many great college comedies have their been? Animal House? Lady and the Tramp? By changing the perspective of the main characters to parents, it gave rise to a lot of unique opportunities.

Kind of like my college experience. Which reminds me, it may be time to end this interview. By the way, to get in the mindset to write this, I may have smoked something illegal. Not that it had any effect on me.

Peace and sama lamaa maka.

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: False conflict is an extension of “movie logic.” Remember, to you the writer, it may be a movie. But to the characters in your script, their world is real. So those characters need to act like real people would. That’s the only way your script comes off as truthful. So Amanda entertaining this relationship with this professor sounds great as a plot twist. But it doesn’t work because we don’t buy that Amanda would really do this. Her character and this script hasn’t been set up that way. So the moment doesn’t play truthfully and truth is essential if you want laughs.

Just 24 days left. The contest is FREE. Winner gets their script optioned by Grey Matter. There’s no better contest deal on the planet! Submit now!

The schizophrenic 2015 Summer box office refuses to go away! Neither of this weekend’s contestants, Terminator: Genisys or Magic Mike XXL, finished in the top two. Those spots went to stellar holdovers Inside Out and Jurassic World. The studios responsible for the new entries, Paramount and Warner Brothers, are trying to blame a weird July 4th weekend layout (where July 4th didn’t fall on a weekday), but come on, let’s be honest here. Nobody wanted to see these films because of a simple reason: they didn’t look that good.

I mean Terminator: Genisys did so bad, it finished 20 million dollars below Terminator: Salvataion’s opening weekend box office, a movie that famously found a way to make a post-apocalyptic world dominated by killer robots boring. What’s strange is that every single person on the planet knew this movie was dead in the water EXCEPT for the Terminator producers and Arnold Schwarzenegger. How can a group of people be so out of touch?

Well, I have a counter-argument for that. I believe that if the script for Terminator: Genisys was good, and that script translated into a good film, word-of-mouth and slamming reviews could’ve saved this film. So why didn’t that happen?

Well, the writers of Terminator: Genysis made an age-old screenwriting mistake. They wrote a complicated time travel story. I’m going to say something here that I BEG all sci-fi writers heed for the remainder of their writing careers: COMPLICATED MAINSTREAM TIME-TRAVEL MOVIES DO NOT WORK.

Time travel is one of the trickiest sub-genres to get right. That’s because they intrinsically don’t make sense. If you travel back in time to stop something and it doesn’t work, you just travel back and try it again. The genre is a black hole for plot holes. And the more you keep travelling around in time, the more of these plot holes keep popping up.

Terminator: Genisys is all about characters travelling back in time to stop moments from previous Terminator timelines. Like an aging Arnold Terminator growing up with Sarah Connor and then fighting his younger Terminator self when he shows up in 1984.

This is a DEADLY but common mistake with young eager sci-fi writers. They say, “Ooh, that’d be so cool. The old Terminator fighting the young Terminator when he arrives in the past!” And it is kind of a cool idea. But if you manipulate a time-travel timeline that’s already iffy as it is solely to accommodate a cool scene, you’ve upset the entire foundation of your story.

When you write anything, whether it’s a complex time-travel plot or a simple coming-of-age film, you must avoid “But wait” moments. “But wait” moments are where your audience pulls out of the movie to ask, “But wait. If that happens, then the other thing doesn’t make sense.” Or, “But wait. If he did this then how come he couldn’t do it earlier?” Time travel movies are cess pools for “But wait” moments.

For that reason, when you write a time travel movie, you keep the time travel stuff as simple as possible. It’s why the original Terminator worked so well. A terminator came back from the future to kill a woman. The whole movie, then, was not about Sarah Conner jumping through time portholes to escape the Terminator. It was a chase movie. Plain and simple. No gimmicks. That’s why it worked.

James Cameron knew this going in for the sequel as well. He didn’t add some silly time-travel plot. The only thing he changed was adding a new Terminator. There was some stuff about trying to destroy Skynet before it could take over the world, but that was still easy to understand and buy into.

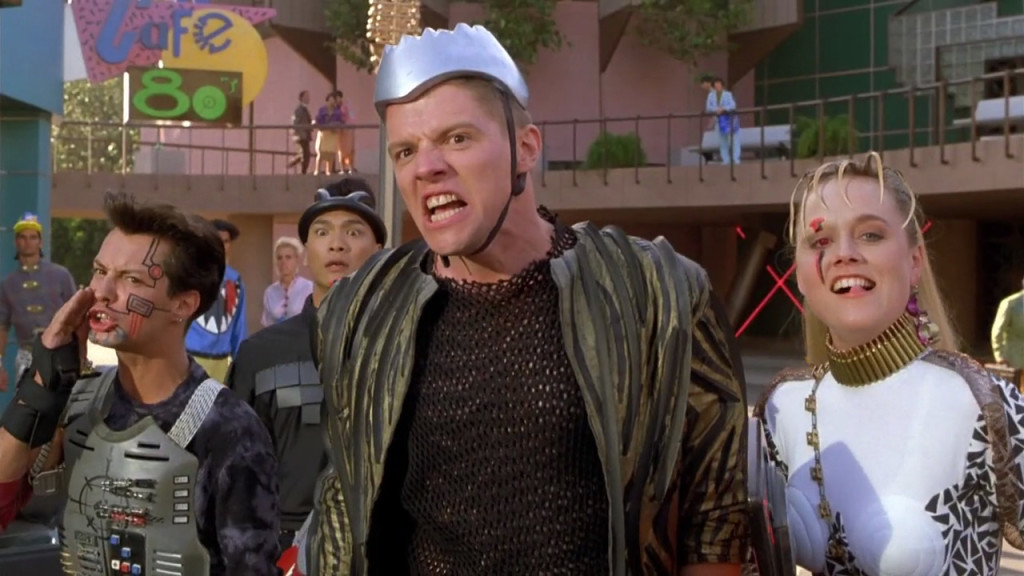

Another example of time travel screwing up a movie was Back to the Future 2. Now I can already hear some of you guys grumbling. “Back to the Future 2 was great, Carson!” No, it wasn’t. The plot was borderline ridiculous. What you liked about Back to the Future 2 (as did I) was that it still had 2 of the most lovable characters in cinematic history, Marty McFly and Doc Brown. Those two are what made Back to the Future 2 watchable.

But the travelling to the future only to find out that they needed to travel to the past to save an alternate present. It was a mess. And I remember Roger Ebert pointing out that even the characters looked confused trying to explain it (needing a chalkboard to do so). And this is yet another reason to avoid complicated time travel movies. They require tons of exposition, which eats up valuable story time.

Now some of you might point out movies like Primer as examples of complicated time travel movies that work. But Primer isn’t a mainstream movie. It’s a $7000 indie movie that nobody outside of cinephiles saw and when you make a movie for that kind of money for that kind of audience, you can take risks and play around because you’re not necessarily required to make sense (and it’s debatable whether Primer does make sense).

My point is, time-travel is a plot device that you can get lost in. And I get it. It’s fun to play with. Who doesn’t want to solve a time travel problem by adding more time travel! But I’m warning you as someone who reads A LOT OF BAD TIME-TRAVEL SCRIPTS, if you’re writing a sci-fi movie, it’s best to keep the time-travel plot as simple as possible. You can be complex with character development and the plot itself. But don’t add layers upon layers of time travel unless you want to “But wait” yourself out of a movie.

Speaking of time travel, I bet the producers of Magic Mike XXL are wishing they could go back in time and not make their sequel.

Granted, my understanding of why this movie didn’t work isn’t as complete as Terminator: Genisys, but I have some ideas. For starters, this isn’t a sequel-type movie. Sequel movies are action movies, adventure movies, sci-fi movies, and comedies. There’s nothing about this particular concept that screams “need more of these.” It feels very much like a “one-off.”

The producers didn’t seem to realize this and that cost them. Because even without that issue looming, sequels need to abide by one law. You need to give the audience MORE. Something bigger. And when you watched the Magic Mike XXL promos, it looked like we were getting the same.

This was the same mistake The Avengers 2 made, which isn’t coming anywhere near the domestic box office of the original. They went as big as they could in the original, leaving them no room to go bigger with the sequel. So people said, “That looks the same.” And it was. It was the same movie (probably even smaller). And that’s death for a sequel.

Using Terminator as an example here, Terminator 2 brought in a bigger badder Terminator. That’s why people showed up to that movie. Because we were getting something new. Magic Mike should’ve realized, “We aren’t a typical sequel film. So we definitely need to find something bigger to bring people in.” I don’t know what that would be. The promise of Channing Tatum full-frontal? Based on the audience for the film, maybe. But a carbon-copy stripper film isn’t going to be enough to lure people to theaters.

Unfortunately, next week doesn’t look much better. Minions is the only major film opening. But the following week we get Ant-Man AND Trainwreck, so that should be fun. And remember, screenwriters – following and dissecting box office is an essential part of your jobs. You need to know what’s doing well and what isn’t, and also WHY. Studios are fickle and terrified and reactionary and one major bomb in a genre can change the development tracks of all six studios. For example, you don’t want to go out wide with your complicated time-travel stripper script this week. Table that for awhile and work on something else. Like dinosaurs attacking Los Angeles or something. I’m only half-kidding. It’s not like Jurassic Park has IP on dinosaurs. Man, the more I think about it, the more I think a studio would actually buy that. Anyway, as always, good luck!

Just 26 days left. The contest is FREE. Winner gets their script optioned by Grey Matter. There’s no better contest deal on the planet! Submit now!