Genre: TV Pilot – Horror

Premise: A small town is plagued with a growing number of demonic possessions. The town outcast, who was shunned after claiming to battle these forces as a child, may now be the only one who can stop them.

About: This show comes from Walking Dead creator Robert Kirkman. Kirkman, looking to expand his empire, has brought his newest pilot to Cinemax, where it has quickly been picked up to series. The show will star Patrick Fugit, a name many of you may have forgotten. Fugit famously played Cameron Crowe’s version of himself in his film, Almost Famous. One of the nice things about this never-ending TV renaissance is that actors who may have been forgotten forever are being given another chance.

Writer: Robert Kirkman (based on the comic created by himself and Paul Azaceta)

Details: 70 pages (6/29/14 draft)

I don’t know what’s going on here, but something doesn’t feel right. Robert Kirkman has an amazing relationship with AMC. With Fear The Walking Dead arriving soon, he’ll have two hit shows on the prestigious network, making him, probably, the network’s biggest star.

So why, then, did AMC not pick up Kirkman’s Outcast? The guy should’ve been able to pitch it in his underwear while dribbling jello onto his belly and AMC fall over themselves to put it on the air. But that’s not what happened. It was sent off to Cinemax, a channel 70% of Americans believe no longer exists.

The only positive scenario I can imagine here is that so many people wanted the next Kirkman show that Cinemax, in a desperate bid to become relevant, overpaid – gave Kirkman a deal AMC couldn’t match. That’s what I’m hoping for, anyway, since that version of the story means I’m about to read a far better script. And with that, I slide into one of my more anticipated pilot reads in awhile.

Outcast begins with one hell of a disturbing teaser. An 8 year-old boy, Joshua, watches as a cockroach skitters up his bedroom wall. Seemingly in a trance, he SLAMS his head into the bug out of nowhere, smearing the roach into two pieces and then, for good measure, eating those pieces (with the bug still wiggling its last bit of life). Joshua, we’ll soon learn, is possessed by a demon.

Cut across town to Kyle Barnes, who lives in a Hoarders-stricken home that he leaves about as frequently as Rob Kardashian. We find out why that is when his sister, Megan, forces him to join her for some errands. Once out in public, everyone who sees poor Kyle looks at him like he’s the Devil.

Throughout the course of the pilot, we learn that Kyle did something horrible to his wife, who’s since taken their little girl and moved away. That wasn’t Kyle’s first strike either. He also beat up him mom when he was a kid. This guy’s got some issues. Or does he? Might there be something more going on here?

When Kyle hears about Joshua being possessed, he goes to his only ally in town, the gambling drinking Reverend Anderson. Anderson knows that Kyle has a gift – a gift to battle the demons inside of others. And so he brings Kyle to Joshua in the hopes of performing an exorcism.

But when Joshua starts talking directly to Kyle, telling him things about his life Joshua couldn’t possibly know, Kyle realizes that these possessions – with his mother, with his wife, with his child – have never been random. They’re targeted. Demons have been possessing the people closest to Kyle for years, trying to get to him. But why? And what is it that they ultimately plan to do to Kyle?

I’m going to tell you what I liked about this pilot. It’s a character piece through and through. And that’s what a pilot needs to be. It needs to be about characters having deep-set issues that date back years. We need this because we’re about to spend years with these characters ourselves and if their issues (with themselves, with each other) aren’t extensive, then there isn’t a whole lot to explore now is there?

I recently watched the pilot for Showtime’s show, Ray Donovan. You can feel a 9.5 Richter Scale-sized earthquake of conflict between Ray and his father, when the two meet for the first time after his dad is released from prison. There’s just so much pain and anger and history there that you want to stick around to see where it all comes from.

With Kyle we have this whole backstory with his mother, who used to beat the hell out of him. We also have something with his sister, who he apparently saved as a child but who now he doesn’t get along with. We have a history between him and his wife (and daughter) that needs to be resolved. We have an entire town who hates him because of this supposedly terrible thing that he did. Those are a lot of character relationships that need to be fixed!

And I liked how Kirkman set that all up. He didn’t just come out and say, “This is what happened to Kyle!” We meet Kyle in the midst of his recluse lifestyle. We see brief flashbacks of his mom locking him in the pantry. We see him try to alienate his sister. We see the way the townspeople feel about him. But we aren’t given straight answers as to how any of this connects. It makes us want to read on! We want to find out what he did that was so horrible (we eventually find out that he either hit his kid or his wife – but not, of course, for the reasons the townspeople think).

So what didn’t I like about the pilot? That it was a character piece through and through. The character stuff is so heavy here, it starts to get overbearing towards the end. If you thought Rick from The Walking Dead was a downer, Kyle’s got him beat by a country mile. This dude’s had a rough life and he’s not afraid to mope about it!

I don’t know. After awhile it was just like, “We get it. Your life sucks.” However, you could make the same argument about all The Walking Dead characters. A lot of them are acting the exact same way today as they did four seasons ago. I actually stopped watching last season because of that. I was like, “Haven’t we seen all of this already?”

Kirkman has a tendency to slip into monodrama, and that’s why The Governor’s Walking Dead season was the best. It brought out all these new sides of the characters (their personality, their energy), and gave the show some variety for once. Reading Outcast, I’m already sensing they’re going to nix variety in favor of long faces and serious storylines.

With that said, I kind of love the concept here. As I’ve said before, with this new TV world emerging, there are all these subject matters that people only used to use for movies that can now be used for television. That’s exactly what they did with The Walking Dead. Zombies used to be exclusively a movie genre. They made it a TV one. Now they’re doing the same with possession/exorcism. I think that’s smart as hell.

I just wish Kirkman would’ve implied a bigger mythology, a bigger plot. I’m all for intimate settings and character driven material but this IS a genre show and therefore we should get a sense of the bigger picture. Right now the bigger picture seems restricted to this town, which isn’t too exciting. Do I really care if Uncle Billy John Bob gets possessed? Not really. But if I felt these possessions were threatening to spread to nearby towns, maybe even the city, now you’ve got my attention.

As it stands, I’ll watch an episode or two to see where this goes. It has me curious but not hooked. Which sucks cause I really wanted to be hooked!

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: I love the 1-2 punch Outcast uses to draw you in. One way to draw a reader in is to introduce a big problem. We get that when we find out Joshua (the little boy) is possessed. Another way to draw a reader in is to introduce a broken relationship. We get that when Kyle and his sister, Megan, get into a fight as soon as they run into each ther. So a perfect way to start a pilot is to introduce BOTH of these scenarios one after the other. Introduce your plot element (the problem) and then your character element (the broken relationship). If you do this well, you’ll have roped us in immediately.

Genre: Comedy (I think?)

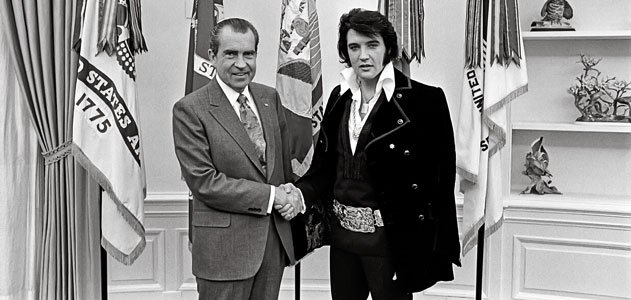

Premise: At 6.30am on December 21st 1970, the King of Rock’n Roll showed up on the lawn of the White House to request a meeting with the most powerful man in the world, President Richard Nixon. He had a very urgent request: to be sworn in as an undercover Federal Agent at large.

About: Elvis and Nixon was acquired by Amazon at the Cannes Film Festival and will star stellar actors Kevin Spacey and Michael Shannon as Nixon and Elvis respectively. The script was written by Joey Sagal, Hanala Sagal, and, in his first screenwriting gig, actor Cary Elwes (presumably off the buzz of his book, “As You Wish.”). This is, indeed, a strange writing team. Joey Sagal is best known for acting in a bunch of cheesy movies (Not Another Celebrity Movie, Anna Nicole, Redline). He’s also played Elvis Presley a number of times in his career, making you wonder if he originally wrote this for himself? Wife Hanala purportedly has over 90 million Youtube viewers and, according to her IMDB page, seven other films in development. I have to admit, this isn’t your typical “hot young writer” scenario we usually see with a buzzed about movie. But hey, why can’t that be a good thing?

Writers: Joey Sagal, Hanala Sagal & Cary Elwes.

Details: 123 pages

I’m telling you right now, the cables and networks and theater chains better watch out. Because the entertainment world is changing faster than you can say Blockbuster Video. Internet giants Netflix and Amazon are digging into their Lord Of The Rings-sized caves of gold to disrupt the whole paradigm.

And while Amazon is putting Elvis and Nixon in theaters first, you get the feeling that the next Elvis and Nixon will be made exclusively for Amazon’s site. And once that happens, coupled with Netflix doing the same, expect a tsunami effect to follow. We’ll never look back.

A note to Amazon though if they expect to compete with Netflix. Rebrand your TV and movie arm. Every time I go to your site to watch a show or a movie, I have to navigate a weird chain of links to do so. It’s so annoying that I’ve found myself avoiding going back because I know how much of a chore it will be. With Netflix I just go to: NETFLIX. It’s pretty damn simple. Make your entertainment arm simple as well and watch the money start rolling in. You’re welcome. I only want an associate producer credit.

Well, the plot of this one pretty much goes how it says in the logline. Elvis is watching TV one night. He sees all the drugs and the flag burning and the Black Panthers and he decides that America has gone to shit.

So he enlists his buddy Jerry Schiller, the only true friend he has in the world, to head to Washington with him so he can meet President Richard Nixon and request to become a “Federal Agent At Large,” even though there’s no such thing – the idea being that he can then help clean up America or something.

Jerry’s tired of being Elvis’s bitch. Every time this happens he upends his life to help the King. Yet against everything telling him to say no, he says yes, and off they go. As soon as the two land, they head straight to the White House. Elvis has written a letter to Nixon detailing his need to become a Federal Agent at Large right away.

Unfortunately, the White House guards tell him that even though they love blue suede shoes, there’s not much they can blue suede do.

Luckily, word of Elvis’s wish meets two young White House aides who happen to be Elvis fans. They ask Nixon if he’ll meet Elvis but Nixon says he thinks the guy’s an idiot. So hell no.

They break the sad news to Jerry, who’s pissed for about five minutes before remembering that Nixon’s daughter is a fan. So he gets word to her that Elvis wants to meet her father, and the next thing Nixon knows, he’s a slave to the demands of his spawn.

The movie ends with the 20-minute long meeting, where a pissy Nixon gradually warms up to Elvis, realizing he’s a great guy who shares a lot of the same political views as the V-fingered figurehead. Nixon surprisingly requests a photo of the pair which would go on to become the single most requested photo from the National Archives in history.

I don’t think I’ve encountered anything this light and fluffy since tripping over my neighbor’s Pomeranian. That’s not necessarily a bad thing. But you’re kind of encouraged, when writing screenplays, to write something with weight, with actual stakes. And the whole time I was reading Elvis and Nixon, I kept asking myself “What are the stakes here?”

I realize that’s a very “Screenwriting Professor” thing to say, and that art shouldn’t be boxed into such restrictive ideologies. So let me put it another way. What happens if Elvis doesn’t get his meeting with Nixon? I’m pretty sure nothing in his life changes. For that reason, this trip, this goal, doesn’t matter. So it was hard to get emotionally invested in the movie.

I mean, the trip obviously matters to Elvis, who’s obsessed with meeting the president and getting this secret badge thing, and that accounts for something. Sometimes you can distract the audience from the low stakes of your story by making the matter so important to the hero that we simply don’t pay attention to the bigger picture.

The problem is, Elvis is painted as such a one-dimensional character here, it’s hard to care about him caring. The King is pretty much played as a joke throughout. Most of the time, he acts like a 12 year-old who wants the hot new cowboy costume for Halloween in order to impress all his friends at school.

He truly honestly wants this secret agent badge so he can infiltrate bad groups of people. Elvis Presley. Infiltrating people UNDER COVER. Which I suppose is funny, and the joke they’re going for, but it comes at the expense of taking your hero seriously. And I personally can’t stand when writers make a joke at the expense of character.

Which leaves “Elvis and Nixon” feeling like one giant curiosity. I spent most of the read trying to understand why such top-level talent would want to make this. And then it hit me. Elvis and Nixon are two of the most iconic caricatures in pop culture history. To get to play one of them must be a dream for an actor. You really get to have fun.

I guess my next question would then be, does Michael Shannon have fun? I’m pretty sure the last time the guy smiled was when he was 8, after watching a school bus full of children drive over a bridge. And this only brings up more questions. Like what is the tone going to be here? I’m guessing they’re going for FULL WEIRD – Charlie Kaufman style – as that’s the only way I can see them justifying this lightweight concept. If you play this straight there’s simply not enough meat on the bone.

In fact, I think this script could’ve been a lot better had it taken its protagonist more seriously. There are these hinted-at moments of Elvis’s complex childhood, as well as repeated mentions of the handlers who control his life. I would’ve liked to have seen his character arc around those issues. See him stand up for himself or something. Instead, we get a pseudo-airhead who believes he’s a secret agent, which just wasn’t meaty enough to justify a feature film in my opinion.

Not saying it won’t work for others. But this was too thin for me. Elvis in his 20’s thin.

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Just say NO to your hero. A lot! — Throughout this script, Elvis keeps getting a “No,” in response to his desire to meet the president. But he keeps fighting and fighting until he finally gets his “Yes.” And really, that’s how every story should work. You give your protagonist a goal, and then you spend the majority of the screenplay saying “No” to him. But he keeps fighting and fighting until he finally gets his “Yes.”

No Amateur Offerings this week, sadly. Next Friday I’ll be reviewing last week’s Amateur Offerings winner, Sessions of Lead Belly. The consensus seems to be that the writing’s a bit raw but that the unique voice makes up for it. You can download and read it here.

In the meantime, remember that there are just 19 days left to enter the Scriptshadow Screenwriting Competition. Feel free to use today’s talkback to discuss box office this weekend (Minions and Self/Less – a script I reviewed a couple of years ago) and any loglines you want to try out. As you know, if something’s not working in logline form, it’s going to be tough to make work in movie form. So make sure that logline’s solid!

Just 20 days left, folks. The contest is FREE. Winner gets their script optioned by Grey Matter. There’s no better contest deal on the planet! Submit now!

So a few months ago this writer wrote into me hyping up his TV pilot. Without getting too specific, it was about a future world in the mold of that new show “Humans” on AMC – the “A.I.” like show about robots being used as slaves. Hearing the writer discuss his script, I don’t think I’d ever been more excited to read something. Not only was it a cool idea, it tackled intense themes like mortality and survival and the power of family. It sounded really good.

And then I read it.

And the script was… not what I had been told it was. It was just so damn… cheesy. There’s no other way to put it. It was a freaking cheese-fest. Like it needed its own display in a Wisconsin supermarket.

But I’m not just an observer at the corner of Swiss and Gouda. I’m a client. I once wrote a tennis script that I thought was going to change tennis forever. It was this deep intense look at a troubled doubles team scraping by on the tour. I gave it to a producer and he didn’t really respond to it. When I pressed him for details on why, he said it reminded him of “that movie Side Out.” I’d never heard of that movie so I looked it up. Here’s the still that I found.

Ouch.

That was not what I was going for AT ALL. But it shows just how pervasive this problem is. And why everyone fears it. I mean, I think we’re all trying to avoid making the next Side Out. James Gunn, the writer-director of Guardians of the Galaxy, had a mini-breakdown in the middle of shooting that film when he became convinced he was making the next Pluto Nash.

Point being, I run into this problem a lot. Writers who go for these really intense dramatic stories that end up coming off super-cheesy. And they don’t know it. And the question becomes, how do you recognize this and fix it before you send your script out and embarrass yourself?

So I got to thinking about that question: What makes a show/movie cheesy? And I came up with a handful of observations. Now to understand what I mean by cheesy, we’re going to look at both extremes, intense drama and cheeseapocalypse. On the “non-cheesy” side, you have something like the Todd Field film, “In the Bedroom.” Here’s a clip from that movie.

As long as we’re talking about rooms, why don’t we hop into an adjacent room for what some consider to be the cheesiest movie of all time. Here’s a scene from, “The Room.”

Now here’s the scary part. Tommy Wiseau, the director of “The Room,” was trying to make a movie like In the Bedroom – something with that kind of power, with that kind of gravitas. What went wrong? That’s an article for another day. But the cheese-factor here can be attributed to a few things, as can most unintentionally cheesy efforts.

1) False Reality – “False Reality” is when you move away from how characters would act in real life and start substituting actions that work specifically for your movie. So if you look at this scene from The Room, Tommy Wiseau reasoned that he needed this scene for his plot. But a big reason why it feels so cheesy is because the scene would never happen in real life. A guy doesn’t sit down on a roof and immediately start talking to someone about girls cheating then leave. Nothing about it feels honest and therefore it screams, “False Reality.” Everything in In The Bedroom’s scene feels honest, like this is the way it would really go down. That authenticity is what wards off the cheesiness.

2) Bad dialogue – The words “cheesy” and “dialogue” go together like peanut butter and jelly. That’s how easy it is to write cheesy dialogue. To avoid this age-old trap, apply the same “false reality” logic to your dialogue as you would your scenes. Ask the question, “Would the characters really be saying this?” Because a lot of times as a writer, you make characters say things in order to move your plot forward or to slip in your observations about life. But you don’t stop to consider if that’s what they’d say in the real world. Now the conversations are never going to sound exactly the same, of course. You have to abbreviate movie-conversations to keep the story moving. But the essence of what they’re saying needs to be necessary. It needs to be truthful. And it needs to be believable. That’s what you need to nail. Also, avoid on-the-nose dialogue at all costs. People rarely say exactly what they’re thinking so when they do, it draws attention to itself, and cheesiness is a by-product of that. So Tommy Wiseau saying, “I’m so happy I have you as my best friend and I love Lisa so much.” Nobody says that kind of thing. That’s why the line is so cheesy.

3) Two-dimensional characters – This one isn’t as easy to spot because it’s less about what’s happening in the moment and more about how much time you put into constructing your characters. The less you know about a character, the more likely it is that they’ll respond to situations in a generic manner. And “generic” is cheese-fuel. Have you ever known someone who speaks in generalities and catch-phrases? “You working hard or hardly working, John?” “That’s my story and I’m sticking to it.” “Looks like somebody’s got a case of the Mondays.” They come off as cheesy right? It’s because they have no depth. Everything they say is surface-level. An act. The same thing goes for your characters. The better you know them, the more specifically you’ll have them act, which in turn makes them more authentic, which is the opposite of cheesy. So write out those extensive backstories, give your characters unique ways of speaking, create complicated relationships for them, give them goals in life, give them unique hobbies, weird stuff they’re infatuated with. Give them that flaw that holds them back. Make sure that flaw dictates everything they do. Make them specific!

4) Stay consistent with your tone – In military parlance, there’s an old saying: “Hold the line.” It’s when you’re shoulder to shoulder in the trenches with your army, shooting down the approaching enemy. Your job is to make sure those guys don’t get past your line. Tonal consistency is a similar idea. You choose a tone for your story and you try and stick to it. The problem is, you get all these goofy, funny, or weird ideas you want to add (the approaching enemy soldiers), and you’re so tempted to just duck down and let them through. You can’t. You’ve chosen this tone so you have you to stick with it. I can’t take your dark funeral drama seriously if one character’s farting all the time. I can’t take your blood diamond action film seriously if one character cracks wise every time he gets in a fight. I can’t take your Leaving Las Vegas type romantic drama seriously if you include the animal cracker scene from Armageddon. Whatever your tone is, hold the line until you get to “The End.”

Like a lot of things in screenwriting, avoiding the cheese tag comes down to truth. If you convey your story and characters and dialogue in a way that feels truthful, we’ll surrender to your world. But if characters are constantly doing things or saying things that they’d never say or do in that situation (or in real life), that’s when shit starts feeling like a big ball of Velveeta. And with that, I leave you with a challenge. Here’s a scene from the zombie show “Z Nation,” which I consider to be really cheesy. I want you to tell me WHY this scene is cheesy. In doing so, consider the show’s polar opposite – “The Walking Dead.” How would THEY have done this scene? Feel free to add your own reasons beyond the four I’ve brought up. The more cheesy rules we end up with by the end of the day, the better.