Search Results for: F word

Genre: Comedy

Premise: A woman goes on a vacation with her much younger boyfriend’s family.

About: Melissa Stack is a lawyer turned screenwriter, which is funny when you think about it, since most parents of screenwriters wish their children would’ve become lawyers. In one of the most notorious Black List entries of all time, Stack’s breakthrough screenplay, “I Want To _____ Your Sister,” became a lightning rod for debate, with many calling the title desperate and gimmicky. The success inspired a slew of similarly titled scripts over the years, until the trend finally died out. While “Sister” still hasn’t been made (last I heard it had been moved from its Wall Street setting to college), Stack did get that all important major Hollywood credit with 2014’s The Other Woman. I say “all important” because after you get that credit is when you start getting PAAAAAAAA-IIIID. Family Vacation was purchased by Fox. And taking matters into her own hands, Stack will be making the script her directing debut.

Writer: Melissa Stack

Details: 120 pages

You may be looking at this genre and thinking, “Romantic Comedy? Did I just get transported back to 1991?” Ah yes, tis true. I’m reviewing a romantic comedy. But alas! Don’t be dismissive. Word on Sunset Boulevard is that after the success of Crazy Rich Asians and Set It Up on Netflix, that the romantic comedy is alive again. Granted, it’s not a living breathing bipedal animal. It’s a tiny organism floating helplessly in an endless sea. But the point is… it’s alive! It’s ALLLIIIVE!!!

Which means that if you’ve written a romantic comedy, maybe, just maybe, people will take a look at it. And that’s way better than the situation two years ago, where if you even mentioned the words “romantic” and “comedy” in a Hollywood office, you were branded on the forehand with the letters “RC” and never allowed to speak of screenwriting again. It’s a rough town, I tell you.

Mia is 39 years old, single, and loving life. Well, okay, she’s not “loving” loving life. There’s a romantic void there, a void she’s been filling with Ben, her hot younger (31) neighbor. If forced to define their relationship, Mia might call it friends with benefits and a side of feelings. But the relationship gets scheduled for an upgrade when Ben asks Mia to join him on his family vacation so he’s “not bored.”

Mia, not really sure what this means, accepts the invitation. She’s quickly introduced to Ben’s oversharing parents, former marine Gus, a man who proudly refuses to defecate during vacation, and Linda, who covertly drugs her husband with valium whenever she needs something from him. The four of them hop in the car and head to their destination – a giant ranch in Utah.

Once at the ranch, they meet up with Ben’s brother Sam and his “11 out of 10” wife, Heidi, as well as numerous other vacationers staying at the ranch. The group participates in a series of activities that include cliff diving and fishing, all while Mia and Ben attempt to stay sane. This isn’t easy, as is demonstrated by Gus having an accidental shit explosion during his cliff dive due to the excessive buildup from refusing to defecate, and then Mia ignorantly jumping in right after him.

Eventually, Mia starts to question why she’s on this trip and what she wants from a guy she never expected anything from more than sex. But when Ben starts throwing words like “marriage,” “babies,” and “love” around, Mia realizes that she’s not getting off this ranch without making a choice that will determine the rest of her life.

Family Vacation is an okay script with a couple of big weaknesses. The first is the hook. This is pitched as a woman going on an awkward family trip with her much younger boyfriend. That sounds like a fun movie to me. We typically see the reverse of this – older guy, younger girl – so by flipping that cliche on its head, this already had a fresh feel. The problem is, Ben isn’t that young. She’s 39 and he’s 31. Therefore, once they’re on the trip, there aren’t any situations to exploit their age difference. They’re all fully grown adults. This would’ve been funnier if Ben was 24 or 25 and the parents were only 50, ten years older than Mia. Now that would’ve been awkward.

The bigger issue, however, is the lack of conflict between Mia and the parents. If we go back to the blueprint for this type of comedy – Meet The Parents – you’ll notice that the reason that script works so well is because the main character, Greg Focker, was so desperately trying to win the approval of his fiancé’s father, Jack. But Jack hated him. That conflict and need to change Jack’s mind is what drove the whole film.

In Family Vacation, the parents like Mia immediately. So there’s zero conflict. Nobody to win over. As a result, there isn’t a lot of conflict to exploit. And let me be clear – conflict is the lifeblood of comedy. It’s where all the laughs come from. The pushing and the pulling, the disagreements, the back and forth. It’s hard to make things funny when everyone’s happy and agreeable. And when you don’t have conflict, you’re forced to come up with nonstop hijinx, like a dad shitting in a lake and our heroine jumping in afterwards. I’m not saying that isn’t funny. But you can’t sustain a hijinx-only approach for very long.

To the script’s credit, things get a little more interesting when Mia and Ben begin to struggle with what they want out of their relationship. The problem was this only highlighted the fact that neither character had a strong motivation to begin with. I never knew what Mia wanted out of this relationship and I didn’t know what Ben wanted either. Contrast this with Greg in Meet The Parents. The only thing in the world he wanted was Pam. Pam was his life. He was willing to die for her. Which is why winning over her father was so important to him. That’s the power of a strong motivation.

That’s not to say you can’t explore not knowing what you want in a script. I actually think indecision is a universal flaw that lots of people relate to. But if you’re going to do that, you need to make it clear, in big bold letters, that that’s your heroine’s fatal flaw. She’s always been indecisive. And once again, she’s being indecisive with this guy. That way, we understand what the endgame for the character is and can play along. Mia’s either going to learn to be decisive or she isn’t.

I’m going to make a wild guess here and assume that the writer, Melissa Stack, is basing this script on her own experience. It reads like someone did something and thought, “This could be a movie.” And it can. But when you’re writing about real-life experiences, you have to change things to make the story better. To me, the hook here is the girlfriend joining the much younger boyfriend on a family vacation. But you have to exaggerate that for a movie. So if Stack’s boyfriend was really 8 years younger, you shouldn’t be afraid to double that.

I like Stack’s writing. Her dialogue is fun. And sometimes her hijinx are funny (Heidi getting bit by a snake in the vagina and Mia being forced to suck the poison out was a highlight). But the lack of a genuine hook here combined with barely any conflict left this one feeling light.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Set your scenes up in a distractive environment. The opening scene of Family Vacation is Mia and her three best friends chatting. Stack could’ve placed this scene in a restaurant or a coffee shop. But she instead placed it at a kid’s birthday party. This allowed for kids to be running around, popping their head in, “I have to pee,” and generally giving the scene a more chaotic unpredictable feel. So if you’ve got a stale scene, consider placing it in a more distractive environment.

It’s a wonderful and rare day here on Scriptshadow. We get to celebrate one of the very few IMPRESSIVE amateur scripts I’ve read for the site. Grab your popcorn and notepad. This should be fun!

Genre: Crime/Drama

Logline: A mob rib breaker turned high school janitor seeks to redeem his violent past by preventing a young girl from making the same mistakes he did, but when drugs and gangs overrun her school, he must risk his cover to clean it up.

Why You Should Read: Writing is the reason I get up in the morning. I have been a Nicholl Fellowship quarterfinalist multiple times, a Page semi-finalist and was the 2016 winner of Screamfest with my screenplay “Plum Island”. My day job working with troubled youths allows a consistent reservoir of unique experiences that I draw upon when creating realistic and fleshed out characters. Why read? “The Janitor” perfectly portrays human complexities in a gritty urban setting and creates cinematic characters that are both mythic and believable.

Writer: Matthew Lee Blackburn

Details: 113 pages

If you’ve been away from Scriptshadow for a few days, you missed that Friday I read a killer amateur script. It’s so rare that we get a great amateur screenplay, I didn’t want to rush a review out. I wanted to take my time, think about the script, then do it justice. Hence why you’re getting the review today.

The biggest surprise about The Janitor is that I’d almost given up on it by page 10. The script started out in a clunky manner, and since past experience tells me these scripts don’t get better as they go on, my mind began powering down. I was still going to read the script. But I wasn’t going to be 100% present.

And then something magical happened. We did a little time jump, began a new storyline, and introduced some of the most realistic characters and situations I’ve encountered in a screenplay all year. Another reminder that it’s possible to turn any reader around, no matter how tired or distracted they are, if you write a great script! Let’s take a look!

Despite his boss’s assumptions, Marty isn’t about to rejoin the criminal life that put him behind bars in the first place. Therefore, when he gets out, the first thing he does is steal a chunk of his boss’s money, buys a new identity, and disappears into rural America, where he eventually finds a janitorial job at Redimere Days, a high school that’s been racked by gangs and drugs.

After living with her grandmother for years, 14 year old Juliet Lloyd’s been sent back to her junkie mom and abusive stepdad’s house, where every day is an assault obstacle course. Her only escape is the 7 hours a day she spends at Redimere High. But as a new student who doesn’t know anyone, even that’s a rough experience.

So it’s nice when one of the popular kids, 18 year-old drug-dealer Mickey Kerr, takes an active interest in her. It’s clear to us that Kerr’s a no-good piece of shit. But with no positive life references, Juliet ends up trusting him. That trust nearly gets her raped by Kerr’s friends at a party. So the next day at school, Juliet beats the shit out of him in front of everyone.

The event puts her in line to be expelled, a decision Ruth, Juliet’s teacher and lone champion, begs the principal to reconsider. A compromise is made. Juliet can remain at school if she does a work study with the understaffed janitor, our friend Marty. Marty, the only person at this school who wants to be left alone more than Juliet, resists, but in the end, both must accept the arrangement.

You wouldn’t think that Juliet would enjoy cleaning toilets, but Marty is so kind, so helpful, that he quickly becomes the only person on the planet she can trust. When Marty learns that Juliet is getting beat up at home, he drives over to her house and frightens her stepdad so bad he pisses himself. Just as it’s looking up for Juliet and Marty, Marty’s old criminal gang finds out where he’s run off to. They show up in town with a simple goal: make Marty pay for ever thinking he could steal their money.

I’m sure a lot of you are asking the question: Why did Carson respond so well to this script as opposed to mine? What is this writer doing that I’m not? One of the things I’m constantly looking for in a screenplay is authenticity. Does what’s happening on the page feel like it represents real life? Or is it a facsimile of real life, a writer’s attempt to conjure up a reality he knows nothing about? 9 times out of 10, it’s the latter. Most writers are throwing characters and sequences on the page that are carbon copies of their favorite movies. They’re not digging into their own lives and giving us their own reality.

What I loved so much about The Janitor is that it feels like real life. For example, in a lot of screenplays, when there’s a kid who’s getting abused, writers will play it safe. Wherever there’s an abusive parent, they’re countered with a protective parent. That’s a very “movie-like” thing to do. You’re considering how the audience is going to respond. You’re considering the resistance producers might have to a 14 year old girl getting abused so intensely. So you wrap things in a buffer, a Hollywood safety net that lets everyone know: “It’s okay, everybody. This is just a movie.”

The Janitor doesn’t do that. The step-dad is an abusive lunatic. But the mom is just as bad. She doesn’t give a shit about Juliet. She’s high all the time. She screams at her nonstop. If the stepdad is swinging the bat, the mom’s placing the ball on the Tee. It was that setup that let me know, this world isn’t “Hollywood safe.” This is the real world, where sometimes people are placed in terrible situations where there are no lifeboats.

And Matthew, the writer, never shies away from this reality. There’s a scene in the script where the dad and Juliet are in his car and he’s mad at her and he just mashes her face into the window. It’s raw and unfiltered and real. And that’s what makes it resonate. But normally, I’d see this scene played safe. The stepdad might verbally abuse her instead. Or the violence might be off-screen. And I’m not saying there’s anything wrong with those choices. But the reason The Janitor works where so many other scripts don’t, is that it’s never afraid to be real. It’s not trying to hide anything.

A great side effect of authenticity is that it does wonders for your dialogue. If you’re mining the reality of a situation as opposed to making it up, characters talk more like real people. They’re more passionate, thoughtful, raw, unfiltered, genuine. And the great thing is, is that a lot of this dialogue writes itself. Remember, you only struggle to come up with words for your characters if you’re trying to artificially force words into their mouths. If you just let them speak, they’ll speak truthfully.

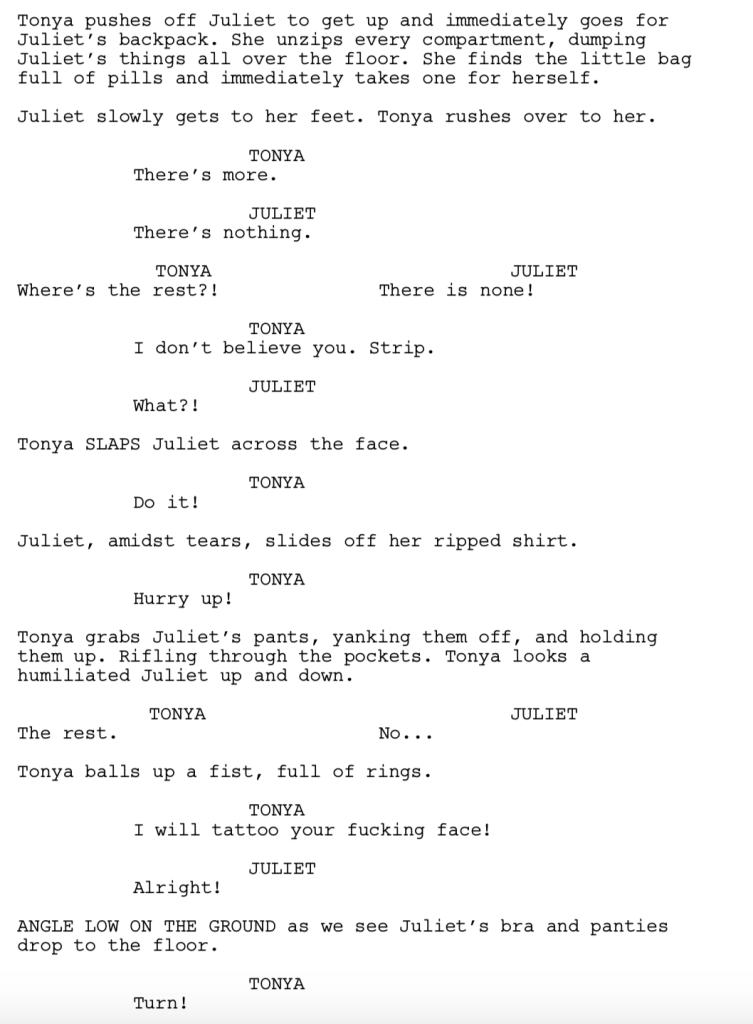

In this scene where Juliet’s mom accuses her of stealing her pills, you’ll see that there are no flourishes to anything anybody’s saying. It’s just one person wanting something and another person resisting. And when you have that, there are no long discussions. It’s a series of brutal clipped statements.

And this scene represents just how unflinching this script is. Juliet is living in a hellhole and we’re never given a break from that. We experience things as she experiences them. She gets attacked at school and needs to regroup? Tough cookies. She comes home and has to deal with her meth-head mom.

Now if you’ve been reading my site for awhile, you know the effect this has on the audience. Readers will always root for characters who are being harmed or taken advantage of. For that reason, we fall in love with Juliet immediately. We want to see her get out of this mess. It’s the driving force for why we must read til the end. To see that she escapes this hell on earth.

One of the tougher challenges with a script like this is finding a way to frame the plot. This isn’t a traditional goal-driven story. Sure, Juliet has to complete her work-study with Marty in order to remain at school, but that’s hardly a plot worth building a script around. So Matthew does something really clever. He creates this looming confrontation. We know that those guys from the beginning are coming back. You don’t get to steal a bag of money from a crime boss and not have to deal with it. So the fact that we know Marty’s going to have to fight off those guys at some point provides the script with a stealthy plot frame.

Remember, as long as we feel like we’re moving towards something big in a story, we’re engaged. GSU may be the easiest model to use. But it’s not the only model out there. It can be argued that The Janitor’s plot is a series of looming confrontations.

Speaking of the opening, that’s the only thing here Matthew has to fix. I noticed a few of you mention he should ditch the opening. But without the opening, we don’t have that looming threat anymore. So the opening needs to stay. But it has to be simpler. The problem is that a man we have no reference for is speaking in voice over. Three characters are introduced quickly afterwards. Everyone’s referring to backstory that we don’t understand. It’s no wonder we’re confused.

In these cases, I always tell the writer: What are the key pieces of information you’re trying to convey? Focus on those things and strip away everything else. All we need to know is that Marty just got out of prison, he used to work for these guys, he wants out, and he sees a way out with the money. Build a scene around that and strip away all the confusion.

But outside of that, I thought this script was spectacular. One of the best amateur scripts I’ve ever read on this site. It bumped right up against my Top 25, almost squeezing in. It very well may get there in the future. I’m going to be talking to Matthew tomorrow and I hope to help him take the next step in his writing career because he deserves it with this script.

Script link: The Janitor

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[x] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: The earlier in the script you are, the more hand-holding you have to do. The Janitor’s only slip up is this opening, where four characters we don’t know and who have a complicated backstory, are thrown at us in the middle of a murder. Something this complicated can’t be rushed through. You need to slow down and hold our hand more, walk us through it so we know what’s going on.

What I learned 2: You don’t have to hold our hand if you simplify the situation in the first place. I just want you guys to know that the simplifying option is always out there. If you’re having trouble explaining an intricate situation to the audience, such as this one, the solution might be to strip out the extraneous elements in order to make everything easier to explain.

What I learned 3: It’s important to note the marketing angle to this idea. The crime aspect. Without it, this is a straight drama, and therefore way more difficult to market. The crime angle makes this a movie as opposed to a screenplay.

The Russo Brothers loved this book so much they’re ditching superheroes for it. So what’s all the hype about??

Genre: War/Drama

Premise: A young man growing up in Cleveland decides to join the army, after which he suffers PTSD, leading to a string of bank robberies to feed his drug addiction.

About: Today’s book was a huge “out of nowhere” million dollar sale, highlighted by the fact that the author, who’s in prison for the crimes he writes about, couldn’t complete the sale for the movie rights because he ran out of his allotted prison phone minutes. He would need to wait a whole extra week to get it done. Meanwhile, the project became so hot that Avengers Infinity War directors Joe and Anthony Russo made Cherry their first post-Avengers directorial project.

Writer: Nico Walker

Details: 300 pages

I was cautiously excited to read this one. Excited because of the rags-to-riches backstory. Cautious because I know Hollywood gets so wet for these war books that they can’t see the forest through the trees. Case in point: Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk. Hollywood LOOOOOVED that book. Couldn’t wait to turn it into a movie and win a billion awards. Except I read that book and it was easily one of the three worst books I’d read in my life. So I was hoping they hadn’t made the same mistake here.

The story follows the author, Nico, in 2003, as he attempts to figure out his life in Cleveland post high school, a life which seems to have no direction other than the love he has for his girlfriend, Emily. When finding a promising job proves difficult, Nico joins the army, and is shipped out for training soon after.

He’s eventually transferred to Iraq where he becomes a medic. His tour is one year, the majority of which is spent cleaning up human remains after IEDs blow up army vehicles. Nico quickly learns that this is war with all of the downsides and none of the glory. There are no soldier-on-soldier battles, just people getting blown up and shot in small skirmishes in the night, and the requisite clean-up afterwards.

Nico bides his time by thinking about Emily, calling her, e-mailing her, and seeing her during the few times he gets time off. Emily is not a fan of what Nico’s doing, and he soon begins to suspect she’s cheating on him. Since Emily is the only thing that keeps him going, he descends into a mental spiral of depression, knowing that if she is sleeping with other guys, there’s nothing he can do about it in Iraq.

When his tour is finally up, his worst fears are confirmed. Emily has been in numerous relationships while he was off in the army. The two break up, and Nico turns to booze and oxycotin, which eventually turns to oxycotin and heroin. He moves from woman to woman, but none of them make him happy the way Emily did.

Eventually, Emily reemerges and Nico gets her hooked on heroin. Every day is a hunt for the next score. When they run out of money, Nico has no choice but to start robbing banks so they can get their fix. When one of the banks publishes a camera shot that is as “clear as if I were sitting for an oil painting” Nico is arrested and sentenced to 11 years in prison. He won’t be released until 2023.

I can totally see why this author is getting attention. His style is raw, in your face, fearless. Most importantly, it’s truthful. One of the hardest things about writing yourself is that you’re always trying to come off as the good guy. Deep down you want people to like you – think you’re funny, cool, interesting, good. So you don’t write the bad things that you think or do. You’re afraid they’ll get in the way of the image you want to portray. The irony is that the bad parts are what make you human, and without them, you don’t seem real, you don’t seem flawed. The most powerful thing about this book is its lack of a filter.

The book also gives you something you can’t get anywhere else. And I think writers forget about this. They forget to ask, “What am I giving the reader that they can’t get with any other story, any other writer?” Because if you’re one of the 95% of writers who are rewriting movies we’ve already seen, why would I need to read your script? I’ve already seen it. Cherry gets extremely specific, especially when we’re in Iraq, and every page is filled with shit I never even thought about. I’m genuinely learning something new in every chapter. Here, after a dead body is called in, Nico and the rest of the crew try to figure out who it might be…

I’m not getting that kind of detail from the screenwriter who does his war research by renting Saving Private and Platoon.

Nico also wisely inserts an anchor into his story. When you’re writing one of these wandering narratives, it’s easy for the reader to feel lost. “Where is all of this headed?” is a common question. You allievaite this by adding an anchor, something to keep coming back to. This anchor grounds the story. The most common anchor used is a relationship. So, for Nico, it’s Emily. Whenever things start to get a little loose, we’ll call Emily, or we’ll e-mail Emily. They did the same thing in Forrest Gump with Jenny.

Nico even turbo-boosted this storyline because he inserted an element of dread into it. It wasn’t just, “Hey, it was nice to talk to Emily again!” There was an underlying sense that she wasn’t as committed to their relationship as he was. Maybe she had found someone else. Since we knew Emily was Nico’s world, we had to keep reading to find out if, indeed, Emily would leave him, or if it was going to be okay.

If the book has a weakness it’s that it’s too depressing. Depressing is fine if it’s earned. If, for example, Nico has this rosy outlook on life and then he experiences the carnage of war and it changes him – that makes sense. But Nico is a downer from the get-go. He’s never a happy guy. So there isn’t enough emotional variance throughout the book. We keep hitting that same “life sucks” beat over and over. Remember, guys – you need highs for the audience to be able to appreciate the lows, and vice versa.

As for the movie adaptation, I’m not sure how the Russos are going to approach it. The most interesting thing about the story is the bank robberies, but those robberies get the least amount of time in the story, as they’re mostly tacked on to the very end. They could focus on the war stuff, but I feel like we’ve seen a ton of Iraq war movies already. On the page this stuff sounds amazing. But I’m not sure it will look any different from the last mainstream Iraq flick. Or the one before that. Nico has such a pronounced voice that I fear this is one of those books that works best as a book, not a film. But we’ll see.

For those interested, this is a good companion piece to Hillbilly Elegy, a book that covers the same demographic, but through the prism of education rather than war. I’d say Elegy is better. But Cherry is still a solid piece of work.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Keep at it. Everything you write will be a struggle. Don’t give up. Nico wrote this book at the urging of a couple of guys working at a small publishing company. He didn’t think he could do it. He only wrote it because they believed in him. After three full years and dozens of rewrites, they gave the manuscript to one of the higher-ups at the company, and he said the writing wasn’t good enough to publish, and so Nico would have to rewrite the whole book over again and so he did. After they finished that version, one of the editors came in and made a few changes to the main character and Nico said, “What the fuck are you doing changing my story?” The editor said that when people read Nico’s version, they think the main character is a total asshole, but when they read this editor’s version, they think Nico is an asshole, but they kind of like him. So they went with the editor’s version.

What I learned 2: If you’re a really good structural writer who’s been told that your description, dialogue or characters are stiff, read this book. It really shows you what can happen if you just let go and write. It literally feels like the words are going straight from the writer’s brain to the page. There’s no, “I have to make this sentence perfect,” filter.

Today I take a second look at a movie that has slowly and quietly become a sci-fi classic.

There is no movie in recent years that has gained more fans after underperforming at the box office than Edge of Tomorrow. I can tell you from personal experience that no fewer than a dozen people (many of them casual moviegoers – not industry types) have said to me, unprompted, a variation of, “You know what’s a great movie that nobody knows about? Edge of Tomorrow.”

When Edge of Tomorrow first came out in script form as a million dollar spec-sale slash adaptation (its original title was “All You Need Is Kill”), I loved it. But the second Tom Cruise came on board, I was confused. The script’s main character was 18, and much of the story was built around the fear you have as an ignorant young soldier. Tom Cruise was 50+ when he was cast. That’s a huge change. How, I wondered, is this going to work after you take away one of the defining elements of the story?

It turns out it didn’t work. Or, at least, it didn’t work for me. In this new iteration, Cruise was a veteran officer who was inexplicably forced to become a soldier. Why? I’ll tell you why. BECAUSE THEY NEEDED A MOVIE. It made zero sense and I never got past it. The entire movie was built off of artificially constructed writer logic to get our way-too-old main character into the same situation that the original, 18 year-old, character had been in. To me, that’s when the movie ended. When it sold logic down the river.

But clearly, others weren’t bothered by this. In fact, I’d guess that if you polled 100 average moviegoers who saw this film, not one of them would’ve brought up this problem. And this speaks to the analysis mindset myself, executives, producers, and agents are obsessed with. You see, we know how difficult it is to get a movie made. We know that the more things that are in place, the better the chance is that the movie will be produced. Therefore, when we see a glaring error like a character who would never be in this situation being placed in this situation, we tell the writer, “You need to change this or else.”

But to an audience member, this makes all the sense in the world. It’s Tom Cruise. OF COURSE he’s going to have to fight. What are you going to do? Have him sit in an office the entire movie? They don’t care how Tom Cruise gets on the battlefield. As long as he gets on the battlefield.

So where’s the disconnect here? Why is it that I get all up in arms about this and won’t accept the movie after the choice is made, yet the people who made the film and the people who watch the film had no problem with it at all? The answer is complicated and comes down to the process a script goes through and how what may be important in one step will not be important in another.

When you’re writing a spec script, it’s crucial you get this kind of plot beat right. Remember, your movie is not getting made at this point. You’re a nobody with words on a page. Therefore, every single beat of your screenplay – in particular the pillar beats, the ones that hold up your story – will be scrutinized. This is why in the original All You Need Is Kill, we have a young scared soldier. Because that’s consistent with the reality of young men getting drafted into war.

However, once your script reaches the “Actor Attached” stage, it’s less about logic and more about getting things as good as you can get them by the time the cameras start rolling. The film is getting made whether you solve the “50 year old dude gets drafted into the army” problem or not. So you do the best you can do, knowing that the audience isn’t going to be as discerning as the script reader who needs things to be as logical as possible to recommend the script to their boss and not get yelled at.

It’s one of the trickier realities about screenwriting – that the same rules don’t apply across the board. While this can be confusing, it’s important to remember that when you’re on the bottom rung and your script needs to stand on its own, plot beats like this have to make sense. You don’t get the “we’re making this movie whether we solve this problem or not” leeway.

This is a long way of saying I wanted to give this film another shot. I want to remove the internal script analyst in me and try to enjoy this film as the 2 hour shot of entertainment adrenaline it became for so many others. And I feel like I have enough distance from the film and its script to do that. With that in mind… what did I think?

For those who’ve forgotten, Edge of Tomorrow follows a public relations officer, Cage, who, due to the escalating nature of an alien invasion, is forced to become an on-the-ground soldier. When Cage is killed during a D-Day attack on a beach, something happens that sends him into a time loop. Every time he dies, he wakes up at the beginning of the day again. This allows him to master the art of battle through repetition, kind of like a video game. Along the way, he meets Rita, a young woman who had the same power as him, but who’s since lost it. Rita uses her knowledge to help Cage find and destroy the mother alien.

Okay!

So what did I think??

You know what. This screening was DEFINITELY better. Way better than I expected. And that surprised me. I was fully ready to feel the same way about the film. The opening still bothers me (in addition to Cage’s age, why are we putting a man in a 5 million dollar suit he’s never trained in before then throwing him into battle an hour later?), but I zen-meditated through it all and focused on the other aspects of the story that did work.

Speaking of, I noticed that the Groundhog Day-like time-looping device was so fun, it helped divert attention away from the script’s weaknesses. I had to remind myself that while I knew the time jumping was coming (because I read the script), the people who skipped this movie in theaters and stumbled onto it on digital were likely shocked when Tom Cruise died in the first fifteen minutes, only to be reborn again. That was the hook point, and once it happened, nobody was thinking about whether a 50 year old would be an army grunt.

The script also handles exposition and plot development much better than I remember. The mythology of the Scourge (the invading alien species) is complex, with a hierarchy of alien fighters, several of which (Alphas) carry an “antennae” feature that allows them to see into the future and direct the army so that the Scourge can always predict the humans’ next move. When Cage kills an Alpha and the blood covers him, he inherits the same power.

It’s far-fetched when you think about it, but in an early exposition scene, a doctor character lays out all of this very simply. As a result, I was never confused about what was going on. That’s a major level-up as a screenwriter – when you can take complex mythology and explain it simply. It’s an art to know just how much information you need to give the reader and not a letter more. And the writers here nailed it.

The script also fixes a loophole that has doomed many a time travel script in the past: non-existent stakes. Remember, whenever a character travels in time and fails, he can just go back in time and try again. This is one of the reasons The Terminator series can’t be revived, despite attempts to do so every five years. We know if the Terminator fails to terminate… they can just send another one. So where are the stakes?

One of the cooler script choices in Edge of Tomorrow is when Officer Cage loses his power before he’s accomplished his goal – to find and kill the future-transmitting alien. Remember, up until this point, he has a safety net (the loop), allowing him to test new things every day. But when that power is all of a sudden gone, the stakes are sky high. He doesn’t get any more lives. Knowing he couldn’t screw up even once in the final act made for a really tense finale.

There are still some things that bother me, such as the fact that we spend the entire first half of the movie trying to bust through the defending Scourge on the beach. However, once they accomplish this, they’re inexplicably able to freely drive a truck down long stretches of country highway. Seeing as we’re on a landmass as giant as Europe, wasn’t there an easier way to get to this highway than through a beach full of killer aliens?

And yes, it still bothers me that there is literally NO reason for why Officer Cage is sent to the front line. They don’t even try to come up with an explanation. The Commander just says, “I’m sending you to the front line,” and that’s it, lol. BUT, at least this time around, I didn’t let it get in the way of the rest of the story. And I’m glad, because if you let that go, you realize that Edge of Tomorrow is a damn good movie.

What I learned: LEVEL UP BY CONSOLIDATING EXPOSITION – One of the most important skills a screenwriter can possess is the ability to take complex mythology and/or plot elements, and distill them down to short and clear exposition passages. Most amateur writers view exposition as information that needs to be conveyed, regardless of length. Instead, they need to see exposition as information that needs to be consolidated.

Sorry for the late post. I spent all last night watching a triple feature of Meg + Crazy Rich Asians + Slender Man. In the process, I was taken to a higher plane of existence where I was told by a man in a purple elephant onesie the meaning of life. I asked the man if I could share the answer with you, but he informed me that I would first have to take a trip to the planet Glufonix and “get initiated” by singing the Seven Hymns of Layamaise to Princess Dave. I chose instead to go to In and Out and sing the seven items of the secret menu. There’s a 5% chance that I was sick and had a fever dream and imagined all this stuff, but I’m fairly certain it was the former. The good news about the wait is that we’ve got some interesting scripts today. I’m personally interested in how three of them turn out. Can’t share which ones, unfortunately. Don’t want to influence the votes!

Here’s how to play Amateur Offerings: Read as many of this weekend’s scripts as you can and VOTE for your favorite in the comments section. Winner gets a review next Friday. — If you’d like to submit your own script to compete on Amateur Offerings, send a PDF of your script to carsonreeves3@gmail.com with the title, genre, logline, and why you think your script should get a shot.

Good luck to all!

Title: Crater Lake

Genre: Drama / Thriller

Logline: When a young widow’s son mysteriously disappears in Crater Lake National Park she will have one week to find him before the snowy season begins & buries any trace.

Why You Should Read: Much of my writing has always been complex, so I took this opportunity to write something simple, short, sweet and a quick read. I call it Flightplan in the woods. Mother loses son and will do everything to get him back, but has everything in her way. Singular park location with limited characters, a mysterious level of suspense and intrigue, mixed with the paranormal. As this is my first foray into something this simple, I’d love to hear any feedback the group has and take in any suggestions.

Title: The Reckoning

Genre: Action/Thriller/Horror

Logline: After being led to investigate the death of a papal candidate, a world-weary, former member of the Swiss guard finds himself embroiled in a dark conspiracy, one that spans across borders, over generations, and if unstopped, will uproot the very fabric of human existence.

Why You Should Read: Hey there! Mike here. Finally decided to throw one of my scripts in the running. Little background first… I went to high school in Rome. There, I met these guys that used to be in the Swiss Guard. We were at a bar one night and they started telling me how they got into it. Basically, they left their homes at the age of twelve to start training for a career that was in their words “a sacred duty.” They finished at the top of their class and were recruited into a special division inside the Vatican. And let me tell you…when your place of work is an ancient city surrounded by walls, the word “special” takes on new meaning. One of their missions involved an extraction of some Catholic parishioners during the Second Congo War that I’m sure would have made headlines if weren’t commissioned by an institution that’s been keeping secrets for thousands of years. So, long story short, I took some of their history, threw my twist on it, added some subtle supernatural elements, and came up with the Reckoning. It’s less Dan Brown, more 24 meets the Exorcist. Hope you enjoy it!

Title: The Trouble With Ringo’s Soul

Genre: Drama

Logline: When the Beatles discover that Ringo sold his soul to be in the band, they make a bet with the Devil to win it back, and in the process create one of the greatest albums of all time.

Why You Should Read: Biographies are hot, but they bore me to death. Bubbles was a nice way to inject some life into a biographical story, but then it faltered because it didn’t really give me what I wanted, which was Michael Jackson. The Trouble With Ringo’s Soul splits the difference, melding the real world Beatles with the movie Beatles to yield a fourth “Beatles” movie. So far it’s not doing well at contests, though I feel like it’s the kinda script that if the right person saw it (maybe a Beatles fan like Ron Howard), it could get some attention. The script might be best suited for animation, or, like, puppets or something.

Title: Easy as Pie

Genre: Comedy, Satire

Logline: When a hardworking, driven sales rep, in need of money for her sister’s operation, battles her conniving rival in a contest involving the world’s first negative calorie pie, she realizes that kindness is an important part of the winning recipe.

Why You Should Read: Many moons ago, I placed a small classified ad in The Toronto Star, seeking people looking for “a great business opportunity” (it was for an MLM program I got roped into and soon abandoned). I only got one response. It was from a young lady. She wasn’t looking for “a great business opportunity.” She was looking to get me involved in her “great business opportunity.” — After I signed up for her MLM program, I got to know her a bit. She was fun, driven and didn’t take “no” for an answer. Even so, I soon lost interest in her program, but I always had fond memories of her. I knew in my tiny little heart she’d make a great lead character in a story exposing the realities of multi-level marketing. — Many years later, I wrote it. And while it started off as a satire on the MLM business, it slowly shifted to a satire on business (and to a certain extent politics) tackling issues such as love, greed, and kindness. — The result is “Easy as Pie,” a “non-serious comedy.” I call it “non-serious” because the plot is centered on something that sadly the world may never see, a negative calorie pie.